Introduction

Recurrent uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common presentation to urologists and family doctors. Survey data suggest that 1 in 3 women will have had a diagnosed and treated UTI by age 24 and more than half will be affected in their lifetime.1 In a 6-month study of college-aged women, 27% of these UTIs were found to recur once and 3% a second time.2

The following topics are reviewed in this guideline. We also include a summary of recommendations (Text box 1).

Text box 1. Summary of recommendations.

|

UTI: urinary tract infection; ACR: American College of Radiology.

Definition of recurrent uncomplicated UTI

Diagnosis of recurrent uncomplicated UTI

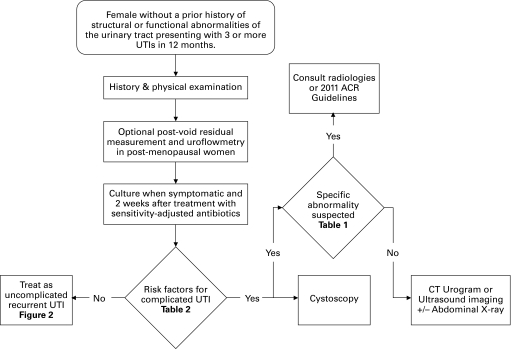

Investigation of recurrent uncomplicated UTI

Indications for specialist referral

Prophylactic measures against recurrent uncomplicated UTI

Methods

Recommendations are made based on systematic searches of Ovid MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE and MacPLUS FS. Where applicable, English studies based on humans from 1980 to April 2011 were included. The following guidelines were also reviewed: Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC, 2010),3 European Association of Urology (EAU, Updated 2010),4 American College of Radiology (ACR, Updated 2011)5 and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG, 2008).6

Definitions

A UTI reflects an infection of the urinary system causing an inflammatory response. Only bacterial infections will be reviewed in this document. A UTI occurs when the normal flora of the periurethral area are replaced by uropathogenic bacteria, which then ascend to cause a bacterial cystitis. Infrequently, this infection ascends to the kidney to cause a bacterial pyelonephritis. Ascending infection is thought to be caused by bacterial virulence factors allowing for improved adherence, infection and colonization by uropathogens. The usual uropathogens include Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis.7

A UTI may be recurrent when it follows the complete clinical resolution of a previous UTI.8 A threshold of 3 UTIs in 12 months is used to signify recurrent UTI.3 The pathogenesis of recurrent UTI involves bacterial reinfection or bacterial persistence, with the former being much more common.8 In bacterial persistence, the same bacteria may be cultured in the urine 2 weeks after initiating sensitivity-adjusted therapy. A reinfection is a recurrence with a different organism, the same organism in more than 2 weeks after treatment, or a sterile intervening culture.9 Although culture remains the gold standard for diagnosis of recurrent uncomplicated UTI, clinical discretion should be applied in accepting a history of positive dipstick tests, microscopy and symptomatology as surrogate markers of UTI episodes.

An uncomplicated UTI is one that occurs in a healthy host in the absence of structural or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract.10 All other UTIs are considered complicated UTIs (Table 1). Although uncomplicated UTI includes both lower tract infection (cystitis) and upper tract infection (pyelonephritis), repeated pyelonephritis should prompt consideration of a complicated etiology.

Table 1.

Host factors that classify a urinary tract infection as complicated

| Complication | Examples |

|---|---|

| Anatomic abnormality | Cystocele, diverticulum, fistula |

| Iatrogenic | Indwelling catheter, nosocomial infection, surgery |

| Voiding dysfunction | Vesicoureteric reflux, neurologic disease, pelvic floor dysfunction, high post void residual, incontinence |

| Urinary tract obstruction | Bladder outlet obstruction, ureteral stricture, ureteropelvic junction obstruction |

| Other | Pregnancy, urolithiasis, diabetes or other immunosuppression |

Diagnosis

Clinical

Physicians should document symptoms patients consider indicative of a UTI, results of any investigations, and responses to treatment. Positive culture, regardless of definition, is predicted by symptoms of dysuria, frequency, urgency, hematuria, back pain, self-diagnosis of UTI, nocturia, costovertebral angle tenderness and the absence of vaginal discharge or irritation.11,12 Factors that predispose to recurrent uncomplicated UTI include menopause, family history, sexual activity, use of spermicides and recent antimicrobial use.13,14 A physical examination, including pelvic examination, should also be performed. The history and physical examination should be focused on ruling out structural or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract (complicated UTI) (Table 1).15

If available, postvoid residual and uroflowmetry are optional tests in postmenopausal women. In a study of 149 postmenopausal women with recurrent uncomplicated UTI and 53 age-matched controls, higher postvoid residual (23% recurrent UTI vs. 2% control, p < 0.001) and reduced urine flow (45% recurrent uncomplicated UTI vs. 23% control, p = 0.004) were present in women with recurrent uncomplicated UTI.16 In combination with other clinical parameters, abnormalities in these tests may suggest complicated UTI (Table 1). In comparison, a study of 213 non-pregnant women aged 18–30 by Hooton and colleagues found no significant difference in postvoid residual volume and urine flow rates between women with recurrent uncomplicated UTI and controls.17

Laboratory

When working up recurrent uncomplicated UTI, culture and sensitivity analysis should be performed at least once while the patient is symptomatic. This workup confirms a UTI as the cause for the patient’s recurrent lower urinary tract symptoms. Additionally, adjustment of empirical therapy based on sensitivity may eradicate resistant bacteria as a cause for bacterial persistence and recurrent UTI.

A midstream urine bacterial count of 1 × 105 CFU/L should be considered a positive culture while the patient is symptomatic.12 Potential for contamination with midstream urine collection necessitates careful evaluation of the cultured species reported. A negative culture, while maintaining a response to treatment, may be present in a minority of women.18 A negative culture and lack of response to treatment suggest another diagnosis. Patients may then be re-cultured 1 to 2 weeks after initiating therapy adjusted to sensitivity to evaluate for bacterial persistence.

Further investigation

Several studies have demonstrated a very low incidence of anatomical abnormalities (0 to 15%) on cystoscopy performed for recurrent UTI.19–24 It, therefore, seems unnecessary to perform cystoscopy on all women presenting with recurrent uncomplicated UTI given this low pre-test probability. The small size of these studies prevented univariate or multivariate analysis to evaluate pre-test risk factors for an abnormal cystoscopy. Nonetheless, some factors suggest complicated UTI and warrant cystoscopy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Indications for further investigation of recurrent urinary tract infection

| Prior urinary tract surgery or trauma |

| Gross hematuria after resolution of infection |

| Previous bladder or renal calculi |

| Obstructive symptoms (straining, weak stream, intermittency, hesitancy), low uroflowmetry or high PVR |

| Urea-splitting bacteria on culture (e.g., Proteus, Yersinia) |

| Bacterial persistence after sensitivity-based therapy |

| Prior abdominopelvic malignancy |

| Diabetes or otherwise immunocompromised |

| Pneumaturia, fecaluria, anaerobic bacteria or a history of diverticulitis |

| Repeated pyelonephritis (fevers, chills, vomiting, CVA tenderness) |

| Asymptomic microhematuria after resolution of infection should be evaluated as per CUA guidelines25 |

PVR: post-void residual CVA: costovertebral angle; CUA: Canadian Urological Association.

Imaging in the setting of all women with recurrent UTI is also unnecessary with a low pre-test probability of complicated UTI (absence of criteria in Table 2). Several series demonstrate a low yield of non-incidental findings following imaging for recurrent UTI and it is not routinely recommended by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC), American College of Radiology (ACR), European Association of Urology guidelines.3,5,9,20–24

When there is high clinical suspicion of an abnormality (Table 2), a computed tomography image of the abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast is the best imaging technique for detecting causes of complicated UTI.25 To minimize radiation exposure, ultrasound imaging of the urinary tract with an optional abdominal X-ray is also appropriate.26–31 Imaging to rule out specific causes of UTI (Table 1) is optimized in consultation with a radiologist or the 2011 ACR guidelines.5

Indications for specialist referral

Most patients with recurrent uncomplicated UTI may be treated successfully by family physicians.32 Specialist referral for recurrent uncomplicated UTI is indicated when risk factors for complicated UTI are present (Table 2). Referral is also indicated when a surgically correctable cause of UTI is suspected (Table 1) or the diagnosis of UTI as a cause for recurrent lower urinary tract symptoms is uncertain. Prior to referral, culture of the urine while symptomatic and 2 weeks after sensitivity-adjusted treatment may aid in confirming the diagnosis of UTI, as well as guiding further specialist evaluation and management.

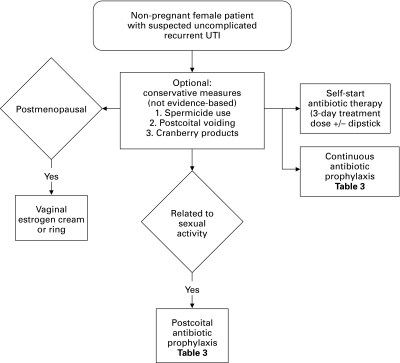

Management

Conservative measures

No good evidence exists for conservative measures in preventing recurrent UTI. Patients may be counselled on modifiable predisposing factors for UTI, including sexual activity and spermicide use.14,33–35 Voiding before or after coitus is also unlikely to be harmful, but there is no evidence for this practice.36 The evidence behind lactobacillus probiotics in UTI prophylaxis is also inconclusive.37,38

Evidence for the effectiveness of cranberry products to prevent UTI is conflicting and no recommendation can be made for or against their use. A Cochrane Database systematic review updated in 2008 suggested that there is some evidence cranberry products may prevent recurrent UTI in women.39 This was based on randomized placebo-controlled trials by Stothers40 and Kontiokari and colleagues41 demonstrating a pooled relative risk of 0.61 (95% CI 0.40–0.91) favouring cranberry over placebo in 241 pooled patients. In 2011, a randomized placebo-controlled trial of cranberry juice versus placebo juice with 319 participants showed no significant difference in UTI recurrence rates between these two groups.42 Various criticisms have been made of each of these studies.9,39,42

Antibiotics

Continuous low-dose antibiotics

Continuous low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis is effective at preventing UTIs. A 2008 Cochrane Database systematic review pooled 10 trials enrolling 430 women in evaluating continuous antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo.43 A meta-analysis of these trials demonstrated that the relative risk for clinical recurrence per patient-year (CRPY) was 0.15 (95% CI 0.08–0.28) favouring antibiotics. The relative risk for severe side effects (requiring treatment withdrawal) was 1.58 (95% CI 0.47–5.28) and other side effects was 1.78 (95% CI 1.06–3.00) favoring placebo. Side effects included vaginal and oral candidiasis, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms. Severe side effects were most commonly skin rash and severe nausea. No additional trials were identified refuting this systematic review.

Because the optimal prophylactic antibiotic is unknown, allergies, prior susceptibility, local resistance patterns, cost and side effects should determine the antibiotic choice.39 Nitrofurantoin followed by cephalexin display the highest rates of treatment dropout.39 Prior to prophylaxis, patients should understand the potential for common side effects and the fact that severe side effects do occur rarely with all antibiotics.44

After discontinuing prophylaxis, women were found to revert to their previous frequency of UTI. Pooling 2 studies demonstrated a 0.82 relative risk (95% CI 0.44–1.53) of microbiologic recurrence per patient-year relative to placebo after discontinuing prophylaxis.39 Six to 12 months of therapy was used in trials demonstrating a benefit; there is no clear evidence to guide treatment after this point, although low-dose trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole has been tried for up to 5 years.57 If patients wish to continue antibiotic prophylaxis for longer periods, they should be advised that there is no long-term safety data for this and there is a small chance of severe side effects44 and resistant breakthrough infections.9

Postcoital antibiotics

Postcoital antibiotic prophylaxis is another effective measure to prevent UTIs in women when sexual activity usually precedes UTI. Stapleton and colleagues conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial with 16 patients in the treatment arm and 11 placebo to demonstrate an 0.3 CRPY in the treatment arm and 3.6 CRPY in the placebo.58 A further randomized controlled trial found no difference in the efficacy of post-intercourse and daily oral ciprofloxacin with 70 patients in the post-intercourse and 65 in the daily group.48 Additional uncontrolled trials have suggested equivalency of other antibiotic regimens.8 Post-coital treatment involves taking a course of antibiotics within 2 hours of intercourse allowing for decreased cost and presumably side effects (Table 3).

Table 3.

Suggested antibiotic prophylaxis39

| Continuous | Postcoital (within 2 hours of coitus) |

|---|---|

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) (40 mg/200 mg daily or thrice weekly)45 | TMP/SMX (40 mg/200 mg to 80 mg/400 mg)46 |

| Trimethoprim (100 mg daily)45,47 | |

| Ciprofloxacin (125 mg daily)48 | Ciprofloxacin (125 mg)48 |

| Cephalexin (125 mg to 250 mg daily)49 Cefaclor (250 mg daily)51 |

Cephalexin (250 mg)50 |

| Nitrofurantoin (50 mg to 100 mg)52 | Nitrofurantoin (50 mg–100 mg daily)46 |

| Norfloxacin (200 mg daily)53 | Norfloxacin (200 mg)56 |

| Fosfomycin (3 g every 10 days)55 | |

| Ofloxacin (100 mg)56 |

Self-start antibiotics

Self-start antibiotic therapy is an additional option for women with the ability to recognize UTI symptomatically and start antibiotics.59–61 Patients should be given prescriptions for a 3-day treatment dose of antibiotics. It is not necessary to culture the urine after UTI self-diagnosis since there is a 86% to 92% concordance between self-diagnosis and urine culture in an appropriately selected patient population.59–61 Patients are advised to contact a health care provider if symptoms do not resolve within 48 hours for treatment based on culture and sensitivity.

Other

Estrogen

Vaginal estrogen may be an effective prophylaxis measure for UTI in postmenopausal women.62 A 2007 Cochrane Database systematic review found two randomized studies which demonstrated a relative risk of symptomatic UTI during the study period of 0.25 (95% CI 0.13–0.50)63 and 0.64 (95% CI 0.47–0.86)64 favouring estrogen in both. Side effects include breast tenderness, vaginal bleeding or spotting, nonphysiologic discharge, vaginal irritation, burning and itching. Vaginal estrogen is also recommended by the SOGC for treatment of atrophic vaginitis and endometrial surveillance for this estrogen-associated cancer is felt to be unnecessary.65 The type of vaginal estrogen is best determined by patient preference. Topical estrogen in the trial involved the use of 0.5 mg of estriol cream vaginally every night for 2 weeks, then twice a week for 8 months. The ring studied was Estring (Pharmacia and Upjohn), an estradiol-releasing ring changed every 12 weeks for a total of 36 weeks. Heterogeneity between studies did not allow a comparison of vaginal estrogens to antibiotics.

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of recurrent urinary tract infection.

Fig. 2.

Management of recurrent urinary tract infection.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Foxman B, Barlow R, D’Arcy H, et al. Urinary tract infection: self-reported incidence and associated costs. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:509–15. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foxman B. Recurring urinary tract infection: incidence and risk factors. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:331–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epp A, Larochelle A, Lovatsis D, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infection. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32:1082–101. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34717-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grabe M, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, Botto H, et al. European Association of Urology: Guidelines on Urological Infections. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segal AJ, Amis ES, Jr, Bigongiari LR, et al. Recurrent lower urinary tract infections in women. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Radiology. 2000;215:671–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 91: Treatment of urinary tract infections in nonpregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:785–94. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318169f6ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Echols RM, Tosiello RL, Haverstock DC, et al. Demographic, clinical, and treatment parameters influencing the outcome of acute cystitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:113–9. doi: 10.1086/520138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooton TM. Recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:259–68. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooton TM. Recurrent urinary tract infection in women. UpToDate. 2011. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/recurrent-urinary-tract-infection-in-women. Accessed September 21, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Campbell MF, Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th edition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL, et al. Does this woman have an acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection? JAMA. 2002;287:2701–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giesen LG, Cousins G, Dimitrov BD, et al. Predicting acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signs. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dielubanza EJ, Schaeffer AJ. Urinary tract infections in women. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooton TM, Scholes D, Hughes JP, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:468–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neal DE., Jr Complicated urinary tract infections. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35:13–22. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raz R, Gennesin Y, Wasser J, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:152–6. doi: 10.1086/313596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hooton TM, Stapleton AE, Roberts PL, et al. Perineal anatomy and urine-voiding characteristics of young women with and without recurrent urinary tract infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1600–1. doi: 10.1086/313528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolle LE. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adults including uncomplicated pyelonephritis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35:1–12. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrentschuk N, Ooi J, Pang A, et al. Cystoscopy in women with recurrent urinary tract infection. Int J Urol. 2006;13:350–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engel G, Schaeffer AJ, Grayhack JT, et al. The role of excretory urography and cystoscopy in the evaluation and management of women with recurrent urinary tract infection. J Urol. 1980;123:190–1. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fowler JE, Jr, Pulaski ET. Excretory urography, cystography, and cystoscopy in the evaluation of women with urinary-tract infection: a prospective study. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:462–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102193040805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Haarst EP, van Andel G, Heldeweg EA, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic workup in young women referred for recurrent lower urinary tract infections. Urology. 2001;57:1068–72. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00971-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mogensen P, Hansen LK. Do intravenous urography and cystoscopy provide important information in otherwise healthy women with recurrent urinary tract infection? Br J Urol. 1983;55:261–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1983.tb03293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickel JC, Wilson J, Morales A, et al. Value of urologic investigation in a targeted group of women with recurrent urinary tract infections. Can J Surg. 1991;34:591–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wollin T, Laroche B, Psooy K. Canadian guidelines for the management of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in adults. Can Urol Assoc J. 2009;3:77–80. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aslaksen A, Baerheim A, Hunskaar S, et al. Intravenous urography versus ultrasonography in evaluation of women with recurrent urinary tract infection. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1990;8:85–9. doi: 10.3109/02813439008994936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer J, Lindsell D, Mastorakou I. Ultrasonography compared with intravenous urography in investigation of urinary tract infection in adults. BMJ. 1990;301:221–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6745.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrews SJ, Brooks PT, Hanbury DC, et al. Ultrasonography and abdominal radiography versus intravenous urography in investigation of urinary tract infection in men: prospective incident cohort study. BMJ. 2002;324:454–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7335.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNicholas MM, Griffin JF, Cantwell DF. Ultrasound of the pelvis and renal tract combined with a plain film of abdomen in young women with urinary tract infection: can it replace intravenous urography? A prospective study. Br J Radiol. 1991;64:221–4. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-64-759-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis-Jones HG, Lamb GH, Hughes PL. Can ultrasound replace the intravenous urogram in preliminary investigation of renal tract disease? A prospective study. Br J Radiol. 1989;62:977–80. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-62-743-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jagjivan B, Moore DJ, Naik DR. Relative merits of ultrasound and intravenous urography in the investigation of the urinary tract. Br J Surg. 1988;75:246–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kodner CM, Thomas Gupton EK. Recurrent urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:638–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholes D, Hooton TM, Roberts PL, et al. Risk factors for recurrent urinary tract infection in young women. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1177–82. doi: 10.1086/315827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fihn SD, Boyko EJ, Chen CL, et al. Use of spermicide-coated condoms and other risk factors for urinary tract infection caused by Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:281–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Handley MA, Reingold AL, Shiboski S, et al. Incidence of acute urinary tract infection in young women and use of male condoms with and without nonoxynol-9 spermi. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sen A. Recurrent cystitis in non-pregnant women. Clin Evid (Online) 2008;pii:0801. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrons R, Tassone D. Use of Lactobacillus probiotics for bacterial genitourinary infections in women: a review. Clin Ther. 2008;30:453–68. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abad CL, Safdar N. The role of lactobacillus probiotics in the treatment or prevention of urogenital infections–a systematic review. J Chemother. 2009;21:243–52. doi: 10.1179/joc.2009.21.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jepson RG, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD001321. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stothers L. A randomized trial to evaluate effectiveness and cost effectiveness of naturopathic cranberry products as prophylaxis against urinary tract infection in women. Can J Urol. 2002;9:1558–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kontiokari T, Sundqvist K, Nuutinen M, et al. Randomised trial of cranberry-lingonberry juice and Lactobacillus GG drink for the prevention of urinary tract infections in women. BMJ. 2001;322:1571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbosa-Cesnik C, Brown MB, Buxton M, et al. Cranberry juice fails to prevent recurrent urinary tract infection: results from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:23–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albert X, Huertas I, Pereiró II, et al. Antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD001209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001209.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cetti RJ, Venn S, Woodhouse CR. The risks of long-term nitrofurantoin prophylaxis in patients with recurrent urinary tract infection: a recent medico-legal case. BJU Int. 2009;103:567–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stamm WE, Counts GW, Wagner KF, et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92:770–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-92-6-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfau A, Sacks T, Engelstein D. Recurrent urinary tract infections in premenopausal women: prophylaxis based on an understanding of the pathogenesis. J Urol. 1983;129:1153–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brumfitt W, Smith GW, Hamilton-Miller JM, et al. A clinical comparison between Macrodantin and trimethoprim for prophylaxis in women with recurrent urinary infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;16:111–20. doi: 10.1093/jac/16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melekos MD, Asbach HW, Gerharz E, et al. Post-intercourse versus daily ciprofloxacin prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infections in premenopausal women. J Urol. 1997;157:935–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinez FC, Kindrachuk RW, Thomas E, et al. Effect of prophylactic, low dose cephalexin on fecal and vaginal bacteria. J Urol. 1985;133:994–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfau A, Sacks TG. Effective prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in premenopausal women by postcoital administration of cephalexin. J Urol. 1989;142:1276–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brumfitt W, Hamilton-Miller JM. A comparative trial of low dose cefaclor and macrocrystalline nitrofurantoin in the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Infection. 1995;23:98–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01833874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey RR, Roberts AP, Gower PE, et al. Prevention of urinary-tract infection with low-dose nitrofurantoin. Lancet. 1971;2:1112–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raz R, Boger S. Long-term prophylaxis with norfloxacin versus nitrofurantoin in women with recurrent urinary tract infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1241–2. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.6.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicolle LE, Harding GK, Thompson M, et al. Prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of norfloxacin for the prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1032–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.7.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rudenko N, Dorofeyev A. Prevention of recurrent lower urinary tract infections by long-term administration of fosfomycin trometamol. Double blind, randomized, parallel group, placebo controlled study. Arzneimittelforschung. 2005;55:420–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pfau A, Sacks TG. Effective postcoital quinolone prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women. J Urol. 1994;152:136–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nicolle LE, Harding GK, Thomson M, et al. Efficacy of five years of continuous, low-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis for urinary tract infection. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:1239–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.6.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stapleton A, Latham RH, Johnson C, et al. Postcoital antimicrobial prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infection. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. JAMA. 1990;264:703–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schaeffer AJ, Stuppy BA. Efficacy and safety of self-start therapy in women with recurrent urinary tract infections. J Urol. 1999;161:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gupta K, Hooton TM, Roberts PL, et al. Patient-initiated treatment of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections in young women. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:9–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-1-200107030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong ES, McKevitt M, Running K, et al. Management of recurrent urinary tract infections with patient-administered single-dose therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:302–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-3-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perrotta C, Aznar M, Mejia R, et al. Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD005131. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005131.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raz R, Stamm WE. A controlled trial of intravaginal estriol in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:753–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309093291102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eriksen B. A randomized, open, parallel-group study on the preventive effect of an estradiol-releasing vaginal ring (Estring) on recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1072–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada SOGC clinical practice guidelines. The detection and management of vaginal atrophy. Int J Gynaec ol Obstet. 2004;88:222–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]