Abstract

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a highly efficacious treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) but adherence to the treatment limits its overall effectiveness across all age groups of patients. Factors that influence adherence to CPAP include disease and patient characteristics, treatment titration procedures, technological device factors and side effects, and psychological and social factors. These influential factors have guided the development of interventions to promote CPAP adherence. Various intervention strategies have been described and include educational, technological, psychosocial, pharmacological, and multi-dimensional approaches. Though evidence to date has led to innovative strategies that address adherence in CPAP-treated children, adults, and older adults, significant opportunities exist to develop and test interventions that are clinically applicable, specific to subgroups of patients likely to demonstrate poor adherence, and address the multifactorial nature of CPAP adherence. The translation of CPAP adherence promotion interventions to clinical practice is imperative to improve health and functional outcomes in all persons with CPAP-treated OSA.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, Continuous positive airway pressure, patient compliance

Introduction

Continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP), a first-line medical treatment in adults with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and an increasingly common treatment option in children with OSA, effectively reduces the apnea hypopnea index (AHI), normalizes oxyhemoglobin saturation, and reduces cortical arousals associated with apneic/hypopneic events.(1, 2) A significant limitation of CPAP treatment is adherence. After the first description of CPAP(3), studies of adult patients’ use of CPAP clearly identified adherence as a problem.(4–6) Similarly, in children treated with CPAP, sub-optimal use of CPAP has recently been identified.(2, 7) Since these initial reports of CPAP nonadherence, particularly in adults with OSA, many studies have been conducted to identify salient factors of CPAP adherence and effective strategies to promote adherence. The purpose of this review is to summarize the evidence focused on CPAP adherence, identify similarities and differences in factors associated with CPAP adherence across age groups, and suggest strategies to promote CPAP use among all patients with a particular focus on children and older adults.

Can CPAP Adherence Be Accurately Measured?

Early studies of patients’ use of CPAP relied on self-report. With the development of technological advances in the CPAP industry, hour meter readings (i.e., device powered on) emerged as a more accurate measure of patients’ use of CPAP. Several studies substantiated that self-reports overestimated CPAP use by approximately 1 hr/night when compared with objectively measured CPAP use.(4, 8, 9) Although hour meter recordings of use were superior to self-report, there was no assurance that the device was actually worn by the patient, at effective pressure, while the machine was powered on. Yet again, technological advances have now produced CPAP devices that measure night-by-night, mask-on CPAP application at effective pressure over each 24-hour period. The 10% difference between machine-on time and mask-on time recorded use illustrates the accuracy of this measure of adherence.(4) A clinical advantage of this technology is that CPAP adherence data can be transmitted to practice sites by several vehicles, including modem, smartcard, or web-portal, depending on the manufacturer. Therefore, early and routine assessment of CPAP use and treatment response, as recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, is possible.(10, 11) Similarly, empiric studies of CPAP adherence have used a true gold standard for measuring adherence, enhancing our understanding of this complex health behavior.

What Amount (i.e., Dose) of CPAP Use Constitutes Adherence?

CPAP is routinely prescribed for use during all sleep periods with the clinical expectation that patients will use CPAP for the duration of sleep. Yet, there is great inconsistency in how CPAP adherence is defined, both empirically and clinically. Three seminal papers reporting CPAP adherence rates in adults were published in the mid-1990s.(4–6) These papers collectively suggested average CPAP use was 4.7 hrs/night in adults in the U.S. and the U.K. Although the authors of these papers did not suggest this was an adequate amount of CPAP use, a common assumption emerged wherein CPAP use of 4 hrs/night on 70% of nights was generally established as a clinical and empiric benchmark of CPAP adherence. This benchmark has recently been examined in terms of dose response.

The question of what level of CPAP yields optimal outcomes and defines adherence has not yet been clearly defined. Several studies have identified that more CPAP (i.e., duration of nightly use) is likely to result in better outcomes. Stradling and colleagues conducted a controlled trial, where change in subjective and objective sleepiness as well as self-reported energy/fatigue was moderately related to hours of therapeutic CPAP use.(12) The same was not found for the placebo CPAP group, receiving pressures between 0.5 and 1.0 cm H2O.(12) A linear relationship between outcome and duration of use was demonstrated, with the best outcome achieved with at least 5 hours/night CPAP treatment.(12) Similarly, Antic and colleagues identified a treatment dose effect for subjective sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale, p < 0.001) among moderate to severe CPAP-treated OSA patients after three months of CPAP use.(13) Normalization of subjective sleepiness was not consistent across participants even with equivalent levels of CPAP adherence. Functional outcomes were responsive to CPAP dose, with greater improvements in Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire [FOSQ] Total scores and activity subscale scores with more CPAP use. Verbal memory and executive function response outcomes were also associated with CPAP adherence, while objective sleepiness (sleep latency, Maintenance of Wakefulness Test) was not associated with CPAP dose.(13) In a retrospective study, differences in 5 year survival rates were shown between those with mean CPAP use < 1 hour/day compared to those using CPAP 1 – 6 and > 6 hours/day.(14) Zimmerman and associates found that memory impairment was eight times more likely to normalize with an average of 6 hours/night CPAP use compared to ≤ 2 hours.(15) Normalization of memory values was significantly different among those using CPAP < 2 hours, 2 – 6 hours, and >6 hours/night.(15)

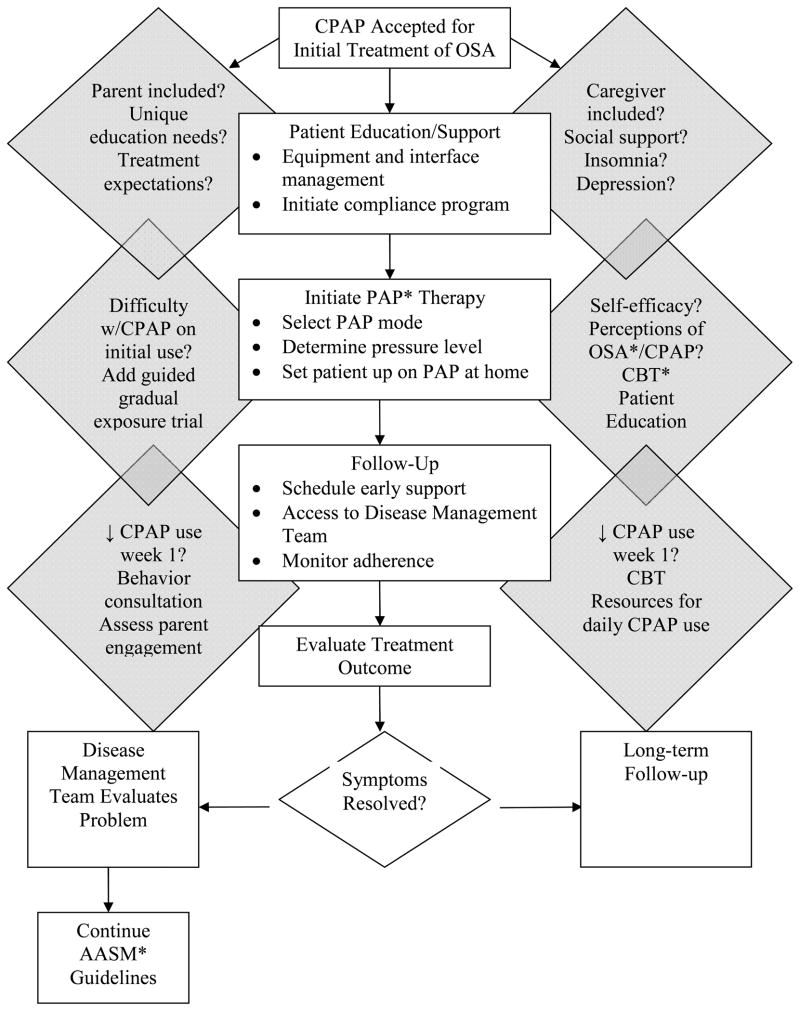

Weaver and colleagues demonstrated that after 3 months of CPAP treatment, average nightly CPAP use (i.e., dose) differentially predicted outcome responses dependent on the outcome examined.(16) As shown in Figure 1, with severe sleep apnea (mean AHI 64.1 ± 29.1 events/hr) and subjective sleepiness at baseline (Epworth Sleepiness Scale [ESS] score >10), the greatest proportion of individuals normalized their subjective sleepiness rating (ESS ≤ 10) with 4 hours/night CPAP use. Objective sleepiness measured by the Multiple Sleep Latency Test required 6 hours/night CPAP use to obtain a value of ≥7.5 minutes in those whose baseline value was below this cut point. For both of these variables there was a linear relationship between hours of nightly use and the proportion of individuals who obtained normal values indicating that further improvement could be obtained beyond these thresholds. A level of normal functional status, measured by the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire, was achieved with 7.5 hours of nightly use to normalize among the greatest proportion of participants with abnormal baseline values, but a linear relationship was evident only up to 7 hours, with no further improvement observed with more use. Based on the results of these studies that examined different clinical outcomes in relationship to CPAP dose, more CPAP use results in better outcomes for many CPAP-treated OSA persons and the historical benchmark of 4hrs/night of CPAP use does not necessarily effectively promote all health and functional outcomes. Examining the dose response for varying outcomes among CPAP-treated OSA persons is critical to understanding the efficacy and effectiveness of CPAP and establishing an empirically-derived benchmark for defining CPAP adherence.

Figure 1.

CPAP Dose and Outcomes of Subjective Sleepiness, Objective Sleepiness, and Functional Outcomes

Cumulative proportion of participants obtaining normal threshold values on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), and Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) by hours of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) use. From Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, Bloxham T, George CFP, Greenberg H, Kader G, Mahowald M, Younger J, Pack AI. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep 2007; 30: 711–19.

What Factors Influence CPAP Adherence?

In order to better understand patients’ decisions to adhere to CPAP treatment, many studies have been conducted to identify factors that influence or predict CPAP use. These studies can be categorized as examining the following factors: (1) disease and patient characteristics; (2) treatment titration procedures; (3) technological device factors and side effects; and (4) psychological and social factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors of Influence on CPAP* Adherence

| Factor | Relationship to Course of Treatment | Caveat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-CPAP Exposure | Initial CPAP Exposure | Home CPAP Treatment | ||

| Disease & Patient Characteristics | Disease Severity | Weak but consistent factor of CPAP use | ||

| Sleepiness | Weak but consistent factor of CPAP use | |||

| Upper Airway Patency | Baseline assessment with acoustic rhinometry; decreased nasal volume/patency may influence initial acceptance of CPAP and reduce overall use of CPAP | |||

| Depression, Mood, Personality Type | Depression, Mood, Personality Type | Influence perceptions of symptoms, response to treatment, and side effects which may deter CPAP use | ||

| Race | Limited evidence in groups other than African Americans, who tend to use CPAP less than Caucasians | |||

| SES* | Neighborhood of residence important and may suggest socioenvironmental factors influential on CPAP use | |||

| Treatment Titration Procedure | Auto-titrating CPAP | Subgroups that may benefit include younger persons, those with persistent side effects, and those who require high pressure | ||

| Technological Device Factors & Side Effects | Heated Humidification | Heated Humidification | Generally recommended for all CPAP users; particularly important for those with oronasal side effects at treatment outset and/or with CPAP use | |

| Flexible Pressure | Add-on therapy in non-adherent users | |||

| Claustrophobia | Decreases over time with persistent CPAP use | |||

| Psychological & Social Factors | Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy | Belief in ability to use CPAP formed at education and with early CPAP exposure is important | |

| Outcome Expectations | Outcome Expectations | Realistic expectations for improvements with CPAP influence use | ||

| Social Support | Provide feedback to CPAP user re: noticeable improvements; Pressure from spouse may deter use | |||

| Disease & Treatment- specific Knowledge | Disease & Treatment- specific Knowledge | Disease & Treatment- specific Knowledge | Contribute to perceptions of OSA* and CPAP but alone likely not influential | |

| Decisional Balance (pros/cons) | If negative aspects of CPAP > positive, use of CPAP may be low | |||

| Active Coping Style | Planful problem- solving and confrontative coping positive influence on CPAP use | |||

| Disease- specific Risk Perception | Contribute to perceptions of OSA and CPAP but alone likely not influential | |||

| Presence of Bed Partner | Improved sleep quality of bed partner with patient’s CPAP use associated with use of treatment | |||

CPAP – Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; SES – Socioeconomic Status; OSA – Obstructive Sleep Apnea CPAP Adherence Interventions

Disease and patient characteristics

The earliest studies to examine influential factors on CPAP adherence focused on disease and patient characteristics. Disease severity, measured as AHI (17–20) and oxygen desaturation (i.e., nadir and time spent <90% during sleep) (18, 21, 22), and self-rated subjective sleepiness (17–20), are the most extensively examined factors. Although these factors are commonly identified as influential on CPAP adherence, the relationships are relatively weak. When other factors are included, disease severity and sleepiness are less contributory to CPAP adherence.

The delivery of CPAP is contingent on the patency of upper airway structures. Several studies have identified a decrease in nasal volume, resulting in increased nasal resistance, influences CPAP use.(23–26) Acoustic rhinometry measures of nasal dimensions at baseline and after three months of CPAP use were examined by Li and associates.(23) CPAP use was significantly lower in those with a smaller nasal cross-sectional area, with CPAP adherence related to minimal cross-sectional area of the nasal cavity (r = 0.34; p = 0.008), mean area of the nasal cavity (r = 0.27; p = 0.04), and nasal cavity volume (r = 0.28; p = 0.03).(23) The minimum nasal cross-sectional area was an independent predictor of adherence, accounting for 16% of the variance, though subjective nasal stuffiness was not different between patients with lower and higher CPAP use and was not associated with acoustic rhinometry-derived nasal dimensions.(23) In a prospective cohort study of 25 newly-diagnosed OSA patients, Morris and colleagues measured acoustic rhinometry at baseline (i.e., at diagnostic polysomnogram) and examined CPAP adherence at 18 months.(25) Forty-eight percent (12/25) were not tolerant of CPAP (i.e., self-reported use < 4hrs/night), with the majority of those patients (91.6%) not using CPAP at all after 18 months. CPAP adherence was associated with the degree of obstruction at the inferior turbinate (p = 0.03). Using receiver operating characteristic analysis, acoustic rhinometry cross-sectional area at the inferior turbinate of < 0.6 cm2 had a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 77% for differentiating CPAP intolerance in this sample.(25) Initial acceptance of CPAP may also be influenced by nasal resistance. In participants with an AHI > 20, those who rejected CPAP after initial exposure (brief nap and titration night) had higher nasal resistance than those who accepted CPAP (p = 0.003).(24) With increased nasal resistance, the odds of rejecting CPAP were almost 50% greater for every increase of 0.1 Pa/cm3/s of nasal resistance.(24) Nasal anatomy, but not necessarily subjective nasal complaints, may be influential on CPAP adherence as is suggested by these preliminary studies.

Few studies have examined depression and mood as influential on CPAP adherence, yet psychological disposition may be an important consideration among adults with CPAP-treated OSA. Although depression and/or low mood at diagnosis/treatment initiation has not been identified as influential on CPAP use, (27, 28) preliminary studies have identified patients’ perceptions of symptoms, including change in symptoms with CPAP treatment, and patients’ perceptions of experiences of side effects, differ among adults with and without depression (29) and Type D (distressed) personality (30) which may in turn influence CPAP adherence. Improved depressive symptoms on CPAP treatment predicted daytime symptom improvement with CPAP use (r = −0.54, p = 0.0001) while more severe baseline depressive symptoms was not associated with daytime symptom improvement (r = 0.19; p = 0.17).(29) Similarly, Brostrom and colleagues identified adults with OSA and Type D personality (n=72), a combination personality type of negative affectivity and social inhibition, perceived higher frequency and severity of CPAP side effects (p < 0.05–0.001) and demonstrated lower objectively measured CPAP adherence (p< 0.001) than adult OSA participants without Type D personality (n=175). Future research is needed to further describe the influence of mood, depression, and personality type on CPAP adherence and explore such relationships in terms of moderators/mediators that may guide the development of adherence interventions among adult OSA patients with concomitant low mood and/or psychological disorders.

There are several studies that have examined race as influential on CPAP adherence, all of which have reported lower CPAP adherence in African American than Caucasian CPAP users.(31–33) Platt and colleagues not only reported differences in adherence between the groups, but also examined other salient factors that may influence these differences in adherence.(32) In a large, retrospective cohort study among veterans with CPAP-treated OSA (n=266), adherence to CPAP was associated with a census-derived neighborhood-level socioeconomic status index, independent of other patient and disease characteristics, including race.(32) This novel finding suggests that socioenvironmental factors are important in terms of disparate outcomes among CPAP-treated OSA patients. From a clinical perspective, this study highlights the need for individualized considerations for initiating and managing CPAP treatment with diverse patient groups. Adherence outcomes for other race and ethnic groups have not been studied and are needed to understand the implications of the currently published studies in the diverse OSA population.

Treatment titration procedure

With increasing demands for sleep diagnostic services, positive airway pressure devices with titration capabilities have emerged and are increasingly common in clinical practice. A meta-analysis of ten studies comparing auto-titrating and standard PAP devices identified no significant differences in adherence between the two modalities.(34) Only age, not mean CPAP pressure or differences in auto-titrating and standard PAP modalities, was significantly associated with adherence differences, with younger participants favoring auto-titrating PAP to CPAP.

Two randomized controlled trials comparing auto-titrating PAP and CPAP also suggest specific OSA patients may achieve better adherence to treatment if treated with auto-titrating PAP.(35, 36) A randomized, single-blinded, parallel crossover study of 46 subjects, each receiving 2 months of CPAP and auto-titrating PAP in random order, identified no difference in adherence between the two treatments.(35) However, there were differences in reported side effects, with fewer adverse effects reported with auto-titrating PAP. Among all subjects who reported any side effect, CPAP adherence was greater in auto-titrating mode as compared with standard mode (median PAP hrs/night 4.65 v. 4.51, respectively, p < 0.001). Massie and colleagues conducted a single-blinded, crossover trial of patients requiring CPAP pressures > 10 cmH2O, randomly assigning patients to CPAP or autotitrating PAP for six weeks.(36) Although no differences between groups were found in the number of nights CPAP was applied, duration of use was significantly higher in the auto-titrating CPAP group (306 ± 114 minutes/24 hours versus 271 ± 115 minutes/24 hours, p<0.005). Based on these studies, adherence outcomes may be enhanced with auto-titrating CPAP for certain subgroups, including patients with persistent side effects on CPAP, those needing higher CPAP pressure for effective reduction of the AHI, and younger patients.

Technological device factors and side effects

Approximately two-thirds of CPAP users experience side effects, though side effects have not been shown to be significantly influential on CPAP adherence.(37) Yet, the amelioration of CPAP side effects has motivated the development of comfort-related technological advances in CPAP equipment. These technologies include nasal and face mask innovations, humidified systems, and pressure modality add-on options. Though patients commonly express concerns about mask comfort and mask-related side effects, relatively few studies have critically examined the effect of mask selection, fit, leaks, and mask changes on CPAP adherence outcomes.(38–41) The trials conducted to date do not suggest CPAP mask interface at the outset of treatment significantly influences CPAP adherence.(38–41) Studies of mask-interface types in both CPAP-naïve patients and in those who fail to adhere to treatment are needed. Similarly, systematically examining patient preference, mask fitting procedures, and mask changes over time and the influence of these factors on CPAP adherence are needed.

To examine the common side effect of nasal/pharyngeal dryness, Massie and colleagues conducted a randomized crossover trial comparing heated and cold pass-over humidity with a 2-week washout period (i.e., no humidity) between humidity exposures as influential on CPAP adherence in a group of 38 newly diagnosed OSA subjects.(42) No differences were found in CPAP adherence between the groups using heated versus cold passover humidity. Those exposed to heated humidity compared to no humidity (i.e., washout period) used CPAP more (5.52 hrs/night v. 4.93 hrs/night; p= 0.008). Seventy-six percent of subjects preferred heated humidity while associating its use with greater satisfaction (p< .05) and feeling more refreshed in the morning (p=0.005). Neill and associates found similar results, except they did not find that humidification affected satisfaction with the treatment.(43) Another randomized controlled trial examining the effects of CPAP heated humidity on adherence, sleepiness, quality of life, and CPAP side effects included 98 subjects with moderate to severe OSA, randomized to CPAP with heated humidity or without humidity (control).(44) There were no significant differences between the groups for CPAP adherence, sleepiness, quality of life, or total side effects. It is possible that humidified CPAP delivery systems may be beneficial in a subset of patients, likely those with dry oronasal complaints at the outset of treatment.

In an effort to promote comfort during exhalation on CPAP, flexible pressure was developed. Flexible pressure permits the patient to select from different early expiratory pressure settings, reducing the airway pressure during early expiration with return to prescribed pressure at the end of expiration when airway collapse is most likely to occur. A cohort study examining the effect of flexible pressure on CPAP adherence, treatment outcomes, and attitudes toward CPAP included a CPAP-naïve convenience sample assigned to standard CPAP (n=41) or CPAP with flexible pressure (n=48).(45) Three month outcomes were measured. The flexible pressure group had higher CPAP use for the entire study period and demonstrated relatively stable rates of use (hrs/night over 12 weeks) as compared with the standard CPAP group. Since this first published study, larger studies have examined flexible CPAP compared with standard CPAP, identifying no differences in overall CPAP adherence among patients newly-initiated on CPAP.(46, 47) However, in patients demonstrating poor adherence with CPAP treatment, flexible pressure may be an add-on option to enhance overall adherence. In a randomized controlled trial wherein low adherers (i.e., < 4hrs/night) were identified in an open arm phase, patients had significantly higher CPAP use on flexible CPAP pressure as compared to their initial 3 months of use on standard CPAP (3.40 ± 1.64 vs. 2.81 ± 0.97, respectively; p = 0.04).(46) Although flexible pressure may not significantly influence adherence to CPAP in all patients, those experiencing difficulty with CPAP may benefit from the addition of flexible pressure.

Finally, though more common side effects of CPAP do not influence adherence, claustrophobia may be a unique consideration. Patients’ initial acceptance of CPAP may be lessened by concerns about claustrophobia, as Weaver and colleagues identified that approximately half of newly diagnosed patients stated that they would not use CPAP if they felt claustrophobic in a study of OSA and cognitive perceptions.(48) In a prospective study examining claustrophobia as influential on CPAP use, Chasens and colleagues found significant differences in baseline claustrophobic scores on the Fear and Avoidance Adapted Scale (a measure of claustrophobia) between those who had < 2 hours, 2 – 5 hours, or ≥ 5 hours of nightly CPAP use.(49) With persistent use of CPAP over three months, claustrophobic scores decreased compared to baseline for the total sample, significantly for those who used CPAP ≥ 5 hrs/night.(49) It is likely that claustrophobia tendencies may deter some patients from using CPAP at the outset of treatment but with persistent use of CPAP, claustrophobia may improve and not necessarily lead to nonadherence.

Psychological and social factors

There is a growing body of literature examining psychological and social factors that influence CPAP adherence. Studies examining these factors have illuminated the multi-factorial nature of CPAP adherence and have substantially contributed insight to the development of interventions to promote CPAP adherence.

Several of the earliest studies of psychological factors and CPAP adherence were theory-derived and designed to examine these factors pre-treatment (i.e., baseline) and after short-term CPAP use (i.e., 1 week of use).(28, 48, 50, 51) The factors of interest include risk perception of disease, treatment outcome expectancies, self-efficacy or the belief in one’s own ability to use treatment even when faced with challenges, coping mechanisms used in challenging situations, and barriers/facilitators with treatment including knowledge, social support, and common treatment-related experiences. With the development and testing of the Self-efficacy Measure in Sleep Apnea (SEMSA), Weaver and colleagues identified that patients’ perceptions of risk related to the OSA diagnosis were commonly inaccurate, not associating their OSA diagnosis with difficulty concentrating, being depressed, falling asleep while driving, having an accident, or having problems with sexual performance or desire.(48) Although some patients realized the benefits of using CPAP, only 66% attributed this therapy to being more alert and only 53% linked CPAP to improved sexual performance and desire.(48) Patients identified important barriers to using CPAP that lessened their confidence in using the treatment including nasal stuffiness, claustrophobia, and disturbance of their bed partner.

Employing the SEMSA in studies of influences on CPAP adherence, both Baron(52) and Sawyer(53) identified self-efficacy and outcome expectancies as important factors. In a recent preliminary prospective repeated-measures study of self-efficacy, daily subjective responses to CPAP, and CPAP adherence, Baron identified self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in ability to use CPAP when faced with difficulties), along with AHI, as important moderators in the relationship of daily perceived response to CPAP, including affect, sleepiness, and fatigue, and three month CPAP adherence.(52) Outcome expectancies (i.e., expectations for particular responses to CPAP treatment), in addition to AHI and self-efficacy, moderated the relationship between three month CPAP use and daily response in affect and sleepiness/fatigue. Notably, higher outcome expectancies were associated with less improvement in daily perceived sleepiness/fatigue, which may indicate unrealistically high expectancies for improvement were not met with CPAP treatment.(52) This study, though preliminary in nature, suggests cognitive perceptions are significant contributors to daily perceived responses of affect and sleepiness to CPAP and adherence. In a prospective, longitudinal study of veterans newly-initiated on CPAP treatment (n=66), Sawyer’s group identified self-efficacy, measured after disease- and treatment-specific education and after one week CPAP use is significantly influential on 1 week and 1 month CPAP use.(53) Baseline cognitive perceptions were not found to influence CPAP adherence.(53) These findings, combined with Baron et al.’s findings,(52) suggest that cognitive perceptions of OSA and CPAP are formulated in the context of receiving patient education about the disease and treatment and during early experiences on CPAP and emphasize the importance of assessing/guiding patients’ formulation of accurate outcome expectancies to promote CPAP adherence.

In other studies of disease and treatment cognitive perceptions, pre-treatment measures of risk perception, outcome expectancies, self-efficacy, and decisional balance also did not influence CPAP adherence.(50, 51, 54) However, after 1 week of experience with CPAP, these variables were influential on short- and longer-term (i.e., 3 months) CPAP adherence. Not only do cognitive perceptions influence CPAP adherence, but also coping processes. Patients’ coping styles with challenging situations (active versus passive) have been shown to be associated with CPAP adherence in a descriptive correlation study wherein 23 CPAP-naïve subjects with moderately severe OSA completed measures of depression, anxiety, stress, anger/hostility, social support, social desirability, and coping prior to treatment.(28) Coping processes, measured by the Ways of Coping scale, was the only variable related to CPAP adherence at 1 week (r = 0.61; p = 0.004). Active, but not passive, coping contributed to 16% of the variance in CPAP adherence, with higher active Ways of Coping scores associated with elevated rates of CPAP use. The active coping styles, including confrontive coping or aggressive efforts to alter the situation and planful problem solving (i.e., deliberate problem-focused efforts to resolve problem), were most explanatory of CPAP adherence.(28)

Collectively, these studies suggest that patients who experience difficulties and proactively seek solutions to resolve problems (active coping) are more likely to be adherent than those who use passive coping styles, though state versus trait components of coping during early CPAP use have not been specifically examined. Further, beliefs (i.e., cognitive perceptions) about OSA and CPAP formed with patient education and in the early treatment period and patients’ confidence in their ability to use this therapy influence CPAP use. Two recently published qualitative studies further confirm these findings.(55, 56) Employing a semi-structured interview based on the health belief model, investigators found that patients who discontinued treatment after 6 months identified few benefits of using CPAP, did not have established treatment expectations, identified many drawbacks, and did not view OSA as a health problem.(55) Similarly, among newly-diagnosed OSA patients who were interviewed immediately post-diagnosis and after the first week of treatment, Sawyer and colleagues identified significant differences between adherers and nonadherers to CPAP that poignantly suggest the importance of psychological and social factors in adherence outcomes (Table 2).(56) These studies, examining the contextual experiences of being diagnosed with OSA and treated with CPAP, are consistent with the earlier studies that indicate the critical role of cognitive perceptions, particularly with treatment experience, in CPAP adherence.

Table 2.

Typologies of Adherent and Nonadherent CPAP* Users

| Adherent CPAP User | Nonadherent CPAP User |

|---|---|

| Define risks associated with OSA* | Unable to define risks associated with OSA |

| Identify outcome expectations from outset | Describe few outcomes expectations |

| Have fewer barriers than facilitators | Do not recognize own symptoms |

| Facilitators less important later with treatment use | Describe barriers as more influential on CPAP use than facilitators |

| Develop and define goals and reasons for CPAP use | Facilitators of treatment absent or unrecognized |

| Describe positive belief in ability to use CPAP even with potential or experienced difficulties | Describe low belief in ability to use CPAP |

| Proximate social influences prominent in decisions to pursue diagnosis and treatment | Describe early negative experiences with CPAP, reinforcing low belief in ability to use CPAP |

| Unable to identify positive responses to CPAP during early treatment |

CPAP – Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; OSA – Obstructive Sleep Apnea

From Sawyer A, Deatrick JA, Kuna ST, Weaver TE. Differences in perceptions of the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure therapy among adherers and nonadherers. Qualitative Health Research 2010; 20: 873–92.

Social factors have also been identified as important to CPAP patients’ decisions to use CPAP. Lewis and colleagues found that CPAP users living with someone had higher use than those who lived alone.(27) Russo-Magno found that older men who were adherent to CPAP were more likely to have attended a CPAP education support group than those who were nonadherent (95% vs. 54%, respectively; p=0.006).(57) The bed partner’s role in patients’ decisions to adhere has also been found to be of importance. McArdle examined the impact of the bed partner’s sleep quality and overall quality of life on the patient’s adherence after one month of objectively monitored treatment (n=23 dyads).(58) Subjective sleep quality and quality of life of patients’ partners were evaluated before treatment and after one month of receiving CPAP or a tablet placebo in a randomized control trial. Prior to treatment the bed partners reported poor sleep quality and impaired daily functioning. Although there were no differences in objective sleep quality between the two treatment groups, partners of patient’s who had received active CPAP, reported better sleep quality (p = 0.05) with less sleep disturbance (p = 0.03). The improvement in the bed partner’s sleep quality was positively related to the patient’s CPAP use (r = 0.5, p = 0.01).

Not only is the presence of social support and influences of the bed partner important to patients’ use of CPAP, but also spousal involvement in patients’ CPAP experience and use. Baron and colleagues conducted a prospective repeated measures study including thirty-one OSA patients and their spouses.(59) Daily measures of spouse involvement in CPAP, including pressure to use the treatment, collaboration with treatment problem-solving, and support, were collected over 10 days beginning within the first week of CPAP treatment. CPAP use was self-reported at 10-days (n=31) and three months (n=20). Although collaboration and spousal support were not significantly influential on CPAP adherence in this preliminary study, spousal pressure to use CPAP was negatively influential on three month CPAP use (− 0.55, p < 0.05). Sawyer and colleagues identified social influences within close proximity (i.e., daily interactions providing support, assistance with trouble-shooting and observing positive responses to CPAP in the patient) are seemingly positive influences on patients’ commitments to CPAP, though the absence of such influences do not necessarily serve as barriers to CPAP use.(56) These studies suggest that CPAP use is influenced by the social environment and includes those social relationships within close proximity to the patient.

Over the past 25 years, studies examining factors that influence CPAP adherence have provided insight to adherence behaviors and suggest opportunities for adherence-promoting interventions, particularly among persons who initially accept CPAP treatment for OSA. Disease and patient factors, technological and side effect factors, and psychological and social factors are all influential on patients’ decisions and commitments to use CPAP and provide opportunities for designing and testing interventions to promote CPAP use. It is noteworthy, however, that future studies of CPAP adherence should also address salient differences among those who initially accept CPAP and those who initially reject the treatment, adherence descriptions for those who use alternative treatment options prior to CPAP (i.e., surgical, weight loss with persistent OSA), and CPAP adherence across varied sub-groups of particular interest (i.e., in persons with hypertension, previous cardiovascular accidents, newly-diagnosed diabetes mellitus). Studies that address these gaps in our current knowledge and practice will further inform interventions to promote CPAP adherence in particular segments of the OSA population.

What Interventions Promote CPAP Adherence?

Recognizing the importance of adherence to CPAP in terms of health and functional outcomes in the OSA population, there is a growing body of literature reporting the effect of interventions on CPAP adherence. Strategies that have been tested are broadly categorized as educational, technological, psychosocial, pharmacological, and multi-dimensional (Table 3). Although some of the interventions have been effective in improving CPAP use, the clinical applicability and cost-effectiveness of any intervention must also be carefully examined. To date, few studies have incorporated these outcomes in their designs. As the discipline moves forward to test the efficacy of CPAP adherence promotion interventions, the effectiveness must also be examined in terms of clinical utility, patient acceptance, cost benefit ratio, and resource utilization. CPAP adherence interventions will then be translational and commonplace in clinical practice, importantly addressing the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s standard for management of the early period of CPAP treatment and recommendations (i.e., consensus) for patients’ with inadequate or suboptimal CPAP adherence.(10)

Table 3.

Intervention Strategies to Promote CPAP* Adherence

| Intervention Strategy & Description | Impact on CPAP Adherence | Caveat |

|---|---|---|

| Educational | NS* | No stand-alone patient education intervention has been effective |

| •Reinforced education by prescriber | ||

| •Reinforced education by homecare provider | May influence patients’ return to clinical follow-up | |

| •One-day education program using video, demonstration, and discussion + spouse in established CPAP users | All effective interventions that follow included patient education | |

| •Simple video education | ||

|

| ||

| Technological | Pilot studies with relatively small sample sizes with negative results; Large trial with positive results | |

| •Telephone-linked communication | + in new CPAP users at 6 months and 12 months | |

| •Telehealth program | + in experienced users at 12 weeks | |

| •Tele-monitoring of CPAP treatment data | NS | Most technological intervention strategies were not statistically effective for CPAP adherence but effect sizes and trend toward statistical significance suggest these may be effective strategies if tested in full studies |

| •Internet-based information, support, and feedback system | NS | |

|

| ||

| Psychosocial | Delivery of CBT prior to home treatment use effective for increasing initial acceptance of CPAP (i.e., starting treatment) and 1 month CPAP adherence CBT may reduce rates of quitting treatment after initiation |

|

| •CBT* | + delivered to small groups, including partners/spouses + effect on discontinuation of CPAP |

|

|

| ||

| Pharmacological | One published study | |

| •Nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotic agent | + eszopiclone 3mg nightly first 14 days of initial CPAP treatment with higher CPAP use at 6 months | May improve sleep quality, relaxation during initial treatment exposure |

|

| ||

| Multidimensional | Intensive home- and sleep- laboratory-support effective for longer-term CPAP adherence | |

| •Intensive support | + for higher CPAP adherence at 6 months | |

| •Combination including education, relaxation, and CPAP habituation | + at 1 month for higher CPAP adherence but not longer term | Consideration of costs important for translation |

CPAP – Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; NS – Not Significant; CBT – Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Educational strategies

Intervention studies examining the effect of patient education on CPAP adherence include varied delivery procedures. To date, educational strategies have not yielded significant improvements in adherence outcomes. Yet, patient education is recognized as a standard of care in the treatment of OSA patients (10) and likely imparts influence on other important factors in patients’ decisions to accept and use CPAP treatment.(53) As has been suggested by Bandura, education alone is not likely an independent influence on health behaviors (i.e., CPAP adherence), but it is an essential part of other domains that are critical to accepting and committing to the behavior.(60)

The largest clinical trial (n = 112, severe OSA) to test an educational intervention to promote CPAP adherence compared four strategies.(61) The conditions included: (1) reinforced education by both prescriber and homecare provider; (2) reinforced education by prescriber and standard care by the homecare provider; (3) standard education by prescriber and reinforced education by homecare provider; and (4) standard education by both the prescriber and the homecare provider, the control. Compared to standard education, reinforced education interventions were delivered with increased frequency and included expanded explanations and demonstrations. CPAP adherence, measured at three, six, and 12 months was not significantly different between intervention groups and the control group. The average adherence for all groups at three and six months was 5.6 hrs/night and at twelve months was 5.8 hrs/night. The inclusion of relatively few nonadherers, indicated by relatively high adherence at three and six months, may have contributed to a ceiling effect.

Applying a variety of educational strategies (i.e. video, demonstration, discussion) in a pre-post (pre-experimental) study of 35 severe OSA patients who had been on CPAP at least six months, patients completed a single-night of in-hospital CPAP titration polysomnogram followed by a one-day educational program with subjects and their spouses.(62) Baseline CPAP adherence was 4.4 ± 0.3hrs/night and increased to 5.1 ± 0.4 hrs/night at three months (non-significant). This pilot study, likely underpowered to detect differences in CPAP adherence, included an educational intervention that was extensive, theoretically-based, and labor-intensive. Employing this strategy in a larger trial, possibly with CPAP-naïve patients, and including measures of cost-effectiveness should be addressed in order to fully understand the effect and utility of this intervention.

In a more abbreviated education intervention, a 15-minute video program that included the definition of OSA, symptoms of OSA, information about CPAP, the sensation of wearing CPAP, and benefits of using CPAP, was tested.(63) Mild OSA participants were randomized to the experimental condition (n = 51; mean AHI 9.6 events/hr) or control condition consisting of initial clinical evaluation and a set of questionnaires (n = 49; mean AHI 8.9 events/hr).(64) CPAP use, measured as machine-on time, for participants who returned for a 4-week follow-up visit, was not associated with the intervention, though there was a significant loss of data at follow-up.(64) The rate of follow-up, however, was associated with video education, with 72.9% of experimental group versus 48.9% of control group returning for follow-up (Χ2 = 5.65, p < 0.02). The video education program may reduce attrition at clinical follow-up, yet it is not clear that CPAP adherence improves with this educational strategy.

From this small group of studies, education interventions are minimally effective in promoting CPAP adherence. Interestingly, no studies of educational interventions have measured the mediating variable of knowledge. It is assumed that by providing education to patients, knowledge is enhanced which then influences adherence to CPAP. Future studies of educational interventions should consider this caveat and examine knowledge as a potential mediator or moderator for the outcome of CPAP adherence.

Technological strategies

Intervention strategies have emerged that capitalize on not only electronic formats of CPAP use data, but also telemedicine technologies. Recently, several investigators have applied telecommunications methods such as computerized telephone systems (65–68) and/or wireless telemonitoring (69) or computerized informational systems (70) to influence patients’ use of CPAP. DeMolles’ group first tested a telephone-linked communication device (TLC) plus usual care compared with usual care alone among CPAP- naïve patients with severe OSA (15 participants per group).(67) The TLC technology functioned as a monitor of CPAP use, educator, and counselor with pre-programmed automated responses delivered to patients in the intervention group based on their own responses to telephone- delivered questions and their CPAP adherence record. Weekly calls were patient-initiated starting on day three of treatment for two months. Though this pilot study did not reveal statistically significant differences between the groups for CPAP adherence (2 month CPAP use, TLC 4.4 ± 3.0 hrs/night vs Usual Care 2.9 ± 2.4 hrs/night, p = 0.076), the study has since been replicated in a much larger randomized control trial (n=250).(68) With weekly calls by patients during the first month of CPAP and monthly thereafter for 12 months, the TLC intervention group’s median CPAP use (n=124) at six months was 2.40 hrs/night and 2.98 hrs/night at 12 months compared with the attention control group’s median CPAP use (n=126) at six months 1.48 hrs/night and 0.99 hrs/night at 12 months. In a final generalized estimating equation model after imputation for missing data, the intervention effect was significant (1.71 hr/night; 95% Confidence Interval 1.17–2.47; p=0.006). To illuminate the intervention factors that were influential on outcomes, the investigators’ mediation analysis identified CPAP self-efficacy and decisional balance indices were significantly important.(68)

Enrolling experienced CPAP users who were identified as nonadherent to treatment, Smith and colleagues tested a telehealth intervention (n=10) compared with a placebo-telehealth condition (n=9) and found higher CPAP use at 12 weeks for the intervention group (Χ2 = 4.55, p = 0.03).(66) Stepnowsky (69) examined the effect of telemonitoring CPAP use with clinical pathway-defined responses to a priori defined nonadherence while Taylor (70) tested the effect of a computer-based “Health Buddy” that provided internet-based information, support and feedback for common challenges with CPAP. Both identified no statistical differences between intervention and control groups for CPAP adherence. These pilot studies, combined with Sparrow’s recently published randomized controlled trial,(68) suggest that telehealth interventions may be highly effective and possibly more cost-effective than other labor-intensive interventions. Replication studies in large randomized control trials are needed to define the effectiveness and utility of the strategies for promotion of CPAP adherence. As social support is a significant influence on CPAP adherence, this type of intervention may be most effective among those CPAP-treated OSA patients without proximate social support.

Psychosocial strategies

Targeting psychological constructs that influence adherence, several studies have employed cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as intervention strategies with some success.(71–73) The earliest study to examine a CBT intervention was a pilot randomized placebo-controlled trial in older adults (age 63.4 ± 4.5 years) with severe OSA, naïve to CPAP.(73) The intervention group received 2–45 minute sessions, one-on-one, that provided participant-specific information about OSA, symptoms, cognitive testing performance, treatment relevance, goal development, changes in symptoms with CPAP, troubleshooting advice, treatment expectations, and treatment goal refinement. There were no differences in short-term CPAP use (i.e., 1 and 4 weeks). At 12 weeks, the experimental group used CPAP for 3.2 hours more than the control group with a large effect size (d=1.27). The results of this pilot study suggest that CBT interventions may effectively address CPAP use over time in older adults.(73) In a larger, randomized controlled trial of 142 middle-aged severe OSA patients, the same intervention strategy was applied focusing on education to promote self-efficacy and decisional balance compared with motivational enhancement therapy and standard care.(71) Interventions were delivered after one week of CPAP use. Both motivational enhancement therapy and education groups had lower discontinuation rates over the 13 week protocol than the standard of care group.

Richards and colleagues examined the effect of a CBT intervention delivered in a group setting in a study of 100 middle-aged adults with moderately severe OSA randomized to the intervention (CBT; n = 50) or the control condition, treatment as usual (n = 50).(72) The CBT intervention, delivered in small group sessions of participants and spouses after diagnosis and before home CPAP treatment initiation, aimed to correct distorted beliefs, promote a positive perspective towards CPAP, and enhance CPAP knowledge. Acceptance or “uptake” of CPAP treatment was greater for the intervention group compared with usual care (p=0.002). The intervention group also exhibited higher CPAP adherence both at 1 week and 1 month than the control group (5.90 hrs/night v 2.97 hrs/night, p < 0.0001; 5.38 hrs/night v 2.51 hrs/night, p < 0.0001, respectively). Importantly, the investigators also examined the psychological constructs of risk perception, outcome expectancies, self-efficacy and social support after the intervention or control exposure and prior to treatment commencement. Self-efficacy and social support were higher in the CBT group than the control condition (4.20 ± 0.72 v 3.6 ± 0.9; p < 0.001; 4.43 ± 0.81 v 3.97 ± 0.88; p < 0.008, respectively). Of note, spousal attendance in CBT intervention was not influential on CPAP use rates at 28 days, yet participants in the intervention group identified higher social support than those in the control condition which may suggest the significance of starting CPAP with a “cohort” of other OSA patients having similar contextual experiences.

These studies suggest that targeting psychosocial factors with interventions to promote CPAP use are likely effective. Future work in this area is needed to understand the utility and acceptability of these interventions in clinical practice and to identify if group and individual interventions are equally efficacious.

Pharmacological strategies

Lettieri and colleagues examined the effects of a two- week course of eszopiclone on CPAP adherence in a randomized, placebo-controlled study of 160 adults starting CPAP therapy.(74) They noted an increase in CPAP usage of 3.57 hours/night versus 2.42 hours/night in the eszopiclone group over a 6 month follow-up period (p=0.005). Study participants were allowed to request sedative-hypnotics during an open-label period starting on day 30: 31% in the placebo group and 19% in the eszopiclone group requested sedative-hypnotics (p=0.084); the mean duration of use was 9.7 days (in the 5 month open-label period) and was similar between groups. Adverse events were similar between study groups. While promising, these findings suggest that additional research is warranted to assess the effects of pharmacologic agents on CPAP adherence.

Multidimensional strategies

Intervention strategies that are comprehensive in nature address the complex and inter-related factors that importantly influence CPAP adherence. Hoys’ group tested a comprehensive intervention, comparing intensive support with standard support in a randomized controlled trial of 80 newly-diagnosed severe OSA patients.(75) Standard support was based on their usual care for newly diagnosed OSA patients and included verbal explanation for CPAP treatment, a 20-minute educational video, a 20-minute acclimatization to CPAP during waking hours, one-night CPAP titration in the laboratory, and telephone follow-up on day 2 and day 21 followed by clinical visits at 1,3, and 6 months. Intensive support included the standard support, with CPAP education provided in the participants’ homes with partners, 2 additional nights of CPAP titration in the sleep center for CPAP troubleshooting during initial CPAP exposure, and home visits by sleep nurses after 7, 14, and 28 days as well as after 4 months. The intervention strategy combined support, education, and self-efficacy promotion with the initial CPAP exposure under supervised conditions. Significant differences in CPAP adherence between the intensive versus standard support groups was identified at 6 months (5.4 ± 0.3 hrs/night vs. 3.8 ± 0.4 hrs/night, respectively, p= 0.003). Although this study provided evidence of the efficacy of the intervention, the resource utilization of the intervention may limit clinical applicability. The study does highlight the importance of addressing adherence from a multidimensional perspective, providing focused intervention at the time of initial CPAP exposure, and including proximate sources of social support during the treatment initiation period.

In one other study, a multidimensional intervention combining education and supportive techniques in a music and habit-forming intervention designed to promote relaxation, CPAP instruction, and habitual application of CPAP was tested.(76) A randomized controlled trial of newly-diagnosed, CPAP naive patients with severe OSA examined CPAP adherence at one, three, and six months among participants assigned to the habit-promoting experimental audio intervention (n = 55) or the placebo audio intervention (daily vitamin consumption; n = 42). Participants were instructed to listen to their audio intervention in the evening (control) or prior to bed (experimental) each night for four weeks. There were more adherers in the experimental group than the placebo group at 1 month (Χ2 = 14.67; p < 0.01) but not at 3 or 6 months.(76) Although this intervention addressed the demands for early habit-formation, relaxation, and positive reinforcement, other intervention opportunities may be needed in order to significantly impact on longer-term CPAP habits and adherence.

What Are Unique Considerations Across Age Groups For CPAP Adherence?

Childhood CPAP-treated OSA and adherence

Although the standard treatment of childhood OSA is adenotonsillectomy, CPAP is increasingly used in children who do not respond to surgery or in those for whom surgery is not recommended. Because CPAP has only more recently been used in children with OSA, the empiric evidence to date regarding CPAP adherence is limited. It is also difficult to extrapolate from adult studies of CPAP adherence to this population. The average sleep need in the pediatric population exceeds that of adults, varies with age and developmental aspects, and the social environment of children is quite different from adults.

Early studies of CPAP treatment in children reported adherence to be generally high, using self-reported or parental-reported measures of CPAP use.(77, 78) Yet, more recent studies using objectively measured CPAP adherence in children, identified less than optimal CPAP use in this population. Marcus and colleagues applied a cutoff of greater than or equal to three hours per night of CPAP use to define “adherence” in their randomized double blind trial comparing effectiveness and adherence of CPAP and bilevel PAP in newly-diagnosed OSA children who were naïve to PAP treatment.(2) There was no difference between treatment groups for adherence outcomes at six months. Adherence for all participants (n = 29) was 3.8 ± 3.3 hrs/night when participants who failed to return for CPAP downloads (n = 8) were assumed to be using zero hours/night of the treatment (i.e., intent to treat analysis). Among participants that returned for follow-up downloads, the average CPAP use was 5.3 ± 2.5 hrs/night. One-third of the enrolled participants dropped out over the six month protocol. Marcus’ group also identified that parents overestimated CPAP use compared with objectively measured use (7.6 ± 2.6 hrs/night v 5.8 ± 2.4 hrs/night, respectively, p < 0.001), similar to findings in adults.(2) O’Donnell and colleagues identified similar CPAP adherence in children aged six months to 18 years in their retrospective cohort study of 65 children with severe OSA.(7) The mean daily use of CPAP was 4.7 hrs/night (IQR 1.4–7.0 hours/night) during the study period (median 207 days; IQR 50–450 days). Interestingly, these investigators identified that children aged 13–18 years and children less than six years old were less likely to accept CPAP treatment at the outset of treatment than children aged six to 12 years. In their retrospective description of adherence in children aged seven to 19 years, Uong and colleagues identified average CPAP use among 23/27 patients who they defined as adherent (i.e., ≥ 4hrs/night) was 7.0 hrs/night over a period of 18 months.(79) Duration of nightly CPAP use (hrs/night) was also associated with frequency of use (% nights/wk used), similar to findings of adults’ patterns of CPAP use.(80, 81) Parental reports of CPAP use were more consistent with objectively measured CPAP use in this study, though objective CPAP use was measured as device powered on, not use at effective pressure. Therefore, it is possible that both the objective and subjective reports of adherence are overestimates.

These studies suggest that CPAP adherence is likely problematic in children, as in adults. Preliminary studies of influential factors on adherence to CPAP in children suggest the following factors may be important: age (7, 79, 82), maternal education (82), mask style (7), length of time to initial acceptance of CPAP by child (7), higher self-reported quality of life (82), and lower BMI (82). Studies that have examined influential factors on CPAP adherence in children identified older children have lower adherence.(7, 79, 82) Yet, most studies did not include infants/toddlers so less is known about CPAP adherence in younger children. Full face masks were associated with lower adherence than nasal masks (7) and lower maternal education was associated with lower CPAP use by children in one study.(82) Interestingly, children who were less readily accepting of CPAP (i.e., > 90 days to first use after CPAP titration polysomnogram) were likely to have lower CPAP adherence as well.(7) Other factors, such as disease severity (i.e., AHI, oxygen saturation), gender, impaired cognition, previous upper airway surgery, concomitant psychological support with CPAP initiation, and mode of PAP delivery (i.e., bilevel vs. CPAP) were not associated with CPAP use. These findings, albeit preliminary, suggest that developmental aspects of childhood, socioenvironmental factors, and initial CPAP exposure factors are important for CPAP adherence in children. There is a great need for more research in this area, particularly if CPAP treatment becomes more commonplace in the treatment of OSA in children.

There is currently one published intervention study available in the extant literature.(83) Koontz and colleagues tested a behavioral intervention aimed at improving CPAP use in children (n = 20) aged 1–15 years who were currently prescribed bilevel PAP and were nonadherent (mean use, 1.44 hrs/night, range 0–8) and assessed adherence at an average of 25 months of follow-up. Children and their parent/guardian(s) self-selected to one of three treatment arms: (1) behavior therapy, (2) behavior consultation and recommendation uptake, and (3) behavior consultation without recommendation uptake. All children and their parents/guardians attended a behavior consultation wherein trained staff observed routine CPAP application, a structured interview provided individualized information about the child’s preferences and dislikes, and recommendations for a one week treatment trial were provided. Behavior therapy was recommended for dyads when behavior recommendations for the treatment trial were not successful. By self-selection, 55% of participants were exposed to behavior therapy, 30% received brief behavior recommendations at the initial consultation, and 15% declined recommendations for behavior therapy. The behavior therapy group attended on average six sessions (SD = 3.1) during which behavior-rehearsal sessions with PAP-related stimuli were presented with increasing proximity and duration. Participants in both the behavior therapy and behavior consultation with recommendation uptake groups demonstrated higher CPAP use than those in the behavior consultation without recommendation uptake group. Differences between the consultation groups with uptake versus without uptake were significant (p < 0.05). Yet, 100% of the participants in consultation with recommendation uptake group and 75% of those in the behavior therapy increased their nightly CPAP use after the intervention. This study suggests that both brief behavior consultations and more extensive behavior therapy programs may be effective interventions for CPAP adherence. Further testing of this intervention strategy is needed in larger, randomized controlled trials to address not only the efficacy of the intervention but also clinical applicability of the intervention in every day practice.

Components of a successful intervention to promote CPAP adherence in children are likely to address child/parent (guardian) engagement in initial acceptance and use of CPAP, patient education tailored to the needs of the child/parent and with emphasis on treatment outcome expectations. In children with complex medical problems or who have previously demonstrated difficulties with CPAP, guided, gradual exposure to CPAP in a supportive setting with anticipatory guidance for troubleshooting difficulties and child responses to the challenges of using CPAP may be indicated. As CPAP use in children grows, particularly with an increasingly obese pediatric population, future studies of varied intervention strategies are needed. Such studies not only need to test CPAP adherence interventions in the setting of scientifically-sound methods, but also examine age- and development-specific intervention strategies that will promote CPAP use in special populations of interest.

Older Adults with OSA and CPAP Adherence

Adherence rates in older adults are generally similar to those observed in other age groups.(84) Russo-Magno and colleagues noted that 64% of older adult males from a Veterans Affairs cohort (33 subjects total, retrospective chart review) were adherent with CPAP as defined by at least five hours of use per night (57), while Pelletier-Fleury and colleagues noted a one-year adherence rate of 71.9% (defined as at least 3 hours/night) in a prospective study that included 70 adults, > 60 years.(85) In older adults (> 60 years) with OSA plus insomnia symptoms, compliance rates may be lower, approaching 40% at four weeks follow-up.(86) Among older adults with Alzheimer’s disease, CPAP use was 5.8 hours/night for 73% of the nights.(87) For patients who are post transient ischemic attack (TIA) and started on auto-CPAP, 40% used their auto-CPAP for at least 4 hours a night on 75% of the nights.(88)

In a Veterans Affairs cohort study comparing rates or average values in adherent and nonadherent participants, lower rates of CPAP were associated with (1) inadequate symptom resolution (resolution of daytime sleepiness, snoring or sleep disturbances occurred in 88–100% of adherers vs. 35–55% of nonadherers); (2) nocturia (present in 32% adherers vs. 83% nonadherers); (3) benign prostatic hypertrophy (present in approximately 4% adherers vs. 43% nonadherers); (4) CPAP initiation at older age (adherers, 72 years vs. nonadherers, 74 years); (5) cigarette smoking (10% adherers vs. 46% nonadherers); and (6) lack of participation in CPAP support/education sessions (95% adherers participated vs. 54% did not participate).(57) Interestingly, functional impairment (ambulation), hearing loss and psychiatric disease were not associated with lower CPAP adherence but indeed had a trend toward higher rates of CPAP use. Less alcohol consumption, lower disease severity (i.e., AHI), and need for supplemental oxygen in addition to CPAP similarly evidenced a trend toward higher CPAP use.(57) No differences were noted between adherent and nonadherent groups in regard to the presence or absence of a live-in partner or vision impairment. In older adults with cognitive impairment (possible or probable mild-moderate Alzheimer’s Disease, Mini-Mental Status Exam score ≥18), patients with higher levels of depression were less likely to adhere to CPAP.(87)

The effect of older age on CPAP adherence is controversial, with some studies showing reduced CPAP use with increasing age (89) while others have noted higher rates of CPAP adherence with age.(90–92) Pelletier-Fleury and colleagues found that age was associated with greater degrees of nonadherence in univariate analysis (71.9% in subjects > 60 years vs. 90.5% in those <60 years), but when controlling for other factors such as gender, age was no longer found to be significantly associated with CPAP adherence.(85) Similar findings using a multivariate model of CPAP adherence have been identified (32), suggesting that any reduced adherence noted as a function of advancing age may be largely mediated by other factors.

Insomnia complaints are common in older adults, and patients with insomnia may also have difficulty adapting to CPAP.(93–96) These patients spend considerable portions of the night awake, and thus have a heightened awareness of the discomfort of CPAP.(97) The net result is that it can be difficult to administer CPAP to patients with significant insomnia complaints.(97) From our clinical experience, patients with upper extremity weakness, such as from rotator cuff tears or cerebrovascular events, may have more difficulty applying a CPAP mask, but this has not been adequately researched. Older adults may also be more likely to have central sleep apnea or complex sleep apnea due to underlying pulmonary or cardiac disease; however, while complex sleep apnea may be associated with more frequent complaints of nocturnal dyspnea or inadvertent mask removal at night, CPAP adherence rates are generally similar.(98)

A limited number of studies have examined interventions to improve CPAP use in older adults. As discussed previously, Aloia and colleagues noted improved adherence to CPAP with two 45-minute CBT interventions.(73) An “intensive support” intervention consisting of education and monthly home visits for six months has also been found to improve CPAP adherence in mostly older adults (average age 57 years) participating in a randomized control trial comparing CPAP with standard support (n = 25), auto-titrating PAP with standard support (n = 25), CPAP with intensive support (n = 25), or auto-titrating PAP with intensive support (n= 25).(99) Auto-titrating CPAP also did not enhance CPAP use.(99) This finding is consistent with studies in adult samples.(34)

Additional interventions that have been proposed include evaluating patients for psychological factors that may influence CPAP adherence, such as depression or claustrophobia, partner involvement, and education regarding risks of untreated sleep apnea in terms of cardiovascular disease and impaired functional outcomes.(84) Other strategies which may have a potential benefit but for which little data is currently available include nap trials to habituate to CPAP and targeted treatment of comorbid insomnia symptoms with pharmacotherapy or CBT.(86, 97)

What are Critical Components of CPAP Adherence Interventions Across and Within Age Groups?

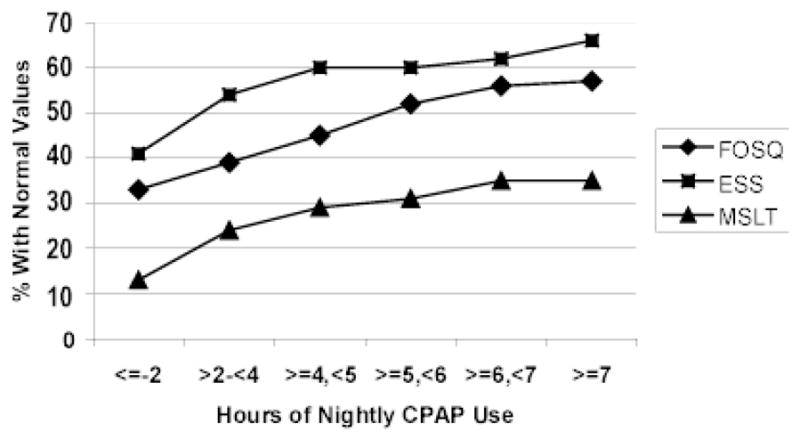

The evidence to date suggests critical components of intervention strategies to promote CPAP adherence in the OSA population likely include: (1) patient education about OSA, diagnostic information, symptoms, CPAP treatment, expectancies for treatment response, expectancies for daily management of CPAP; (2) goals for treatment and use of CPAP; (3) anticipatory guidance for troubleshooting common problems and experiences with CPAP; (4) assisted initial exposure to CPAP; (5) inclusion of support person(s) during early treatment education and exposure (e.g., spouse, bed partner, proximate social support resource); (6) interface opportunities with other CPAP-treated OSA persons; (7) “early and often” follow-up during first weeks of CPAP treatment; (8) available resources for problem-solving; and (9) clinical follow-up with sleep team. Although these components are based on a relatively small number of intervention studies in adult samples, there is consistency from these studies to support these components. Furthermore, preliminary evidence also supports novel components for intervention strategies among younger and older OSA patients (Figure 2). The identified critical components for intervention strategies to promote CPAP adherence are consistent with and further extend the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s clinical guidelines for the management of CPAP-treated OSA.(10)

Figure 2.

Intervention Components to Promote CPAP* Adherence: Pediatric and Older Adult Considerations

Add-on considerations (shaded diamonds, left side for children; right side for older adults and older adults with cognitive impairment) to promote CPAP use in children and older adults based on currently published studies. These suggestions extend the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force recommendations.

*CPAP – Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; PAP – Positive Airway Pressure; OSA – Obstructive Sleep Apnea; CBT – Cognitive Behavior Therapy; AASM – American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

Flow diagram adapted with permission from Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, Ramar K, Rogers R, Schwab RJ, Weaver EM, Weinstein MD. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(3): 263–76.

When examined collectively, there is insightful evidence to suggest broad components that are significant for developing and testing interventions to improve CPAP adherence in adults. Future studies for both the pediatric and older adult OSA populations are needed to suggest intervention opportunities in these populations. Furthermore, there are no published studies in the area of individualized (i.e., tailored) or targeted (i.e., patient-centered) interventions for particular subgroups of patients, including but not limited to established non-adherers, specific age-groups of children, older adults without proximate social support, and older adults with cognitive impairment of varied severity. There is also little work in the area of culturally-congruent interventions for diverse CPAP-treated OSA populations, who are likely to have specific comorbidities that heighten health risks with sub-optimally treated OSA. Translational studies across all age groups are yet another area of critical examination that is not well-described or understood. The gaps in the current literature will need to be addressed in order to (1) better understand if CPAP adherence can be effectively promoted, particularly in different age groups and in particular subgroups of interest, and (2) to place intervention strategies in the clinical setting where patients and providers must address the complexity of effectively treating OSA to promote health and functional outcomes of this population.

Research Agenda Points.

Adults and Older Adults with CPAP-treated OSA:

Further describe CPAP adherence across (1) varied age cohorts and comorbid conditions; (2) extensively explore differences between those who initially accept CPAP and those who initially reject CPAP; and (3) examine the impact of CPAP adherence in terms of measurable health and societal costs

Examine factors that may poignantly influence differences in CPAP adherence in diverse OSA groups which will guide the development of culturally-congruent intervention opportunities

Develop and test a method by which OSA patients at risk for CPAP adherence difficulties can be prospectively identified to permit intervention delivery at the outset, or prior to, CPAP treatment initiation

Examine CPAP dose response across outcomes and adult age groups, including in patients with comorbid conditions that heighten risks of OSA

Further examine the efficacy and effectiveness of CBT interventions for translation

Replicate technologically-based intervention studies in large randomized control trials

Develop and test targeted and tailored interventions to promote CPAP adherence

In multifaceted intervention studies, critically examine not only the primary outcome of interest (i.e., CPAP adherence) but also the moderators/mediators of importance and cost-effectiveness of such interventions

Children with CPAP-treated OSA:

Further describe CPAP adherence in the pediatric OSA population including dose of CPAP that should equate “adherence” in this population

Examine salient factors that influence CPAP adherence in the pediatric population which will potentially guide the development of intervention strategies

Further examine age- and development-related factors that may influence CPAP use and guide targeted interventions based on age and developmental stage

Considering there are unique sub-groups of children likely to use CPAP for OSA, design and test targeted and/or tailored interventions to promote CPAP adherence in these groups

Practice Points.

-

Certain patients may be at risk for CPAP adherence difficulties including

School-aged children and adolescents

Children and adults without proximate social support resources

Adults with reduced nasal cross-sectional area

Claustrophobia at treatment initiation

Persons expressing low belief in ability to use CPAP and/or unable to identify reasons for using CPAP or outcome expectation

Persons who experience difficulties with CPAP at initial exposure or have a negative experience with CPAP during early home treatment period

Persons with upper extremity weakness and physical impairment limiting the ability to apply CPAP and manage the tasks associated with treatment

Patient education is a supportive mechanism to promote CPAP adherence and should be consistently implemented with all patients and their support persons prior to initiating CPAP treatment

-

Intervention strategies to promote CPAP adherence may include

Inclusion of support person(s), parent/guardian, caregiver, spouse/bed partner

Promote positive first experiences with CPAP, including during in-laboratory polysomnogram treatment trials

Anticipatory guidance for common problems, side effects, trouble-shooting device issues

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research K99NR011173 (Sawyer AM).

Abbreviations

- CPAP

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure

- OSA

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- AHI

Apnea/Hypopnea Index

- PAP

Positive Airway Pressure

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SES

Socioeconomic Status

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gay P, Weaver TE, Loube D, Iber C. Evaluation of positive airway pressure treatment for sleep-related breathing disorders in adults. Sleep. 2006;29:381–401. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *2.Marcus CL, Rosen G, Ward SL, Halbower AC, Sterni L, Lutz J, et al. Adherence to and effectiveness of positive airway pressure therapy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e442–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan CE, Berthon-Jones M, Issa FG, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet. 1981;1:862–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Schubert NM, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. American Review of Repiratory Diseases. 1993;147:887–95. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engleman HM, Martin SE, Douglas NJ. Compliance with CPAP therapy in patients with the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax. 1994;49:263–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeves-Hoche MK, Meck R, Zwillich CW. Nasal CPAP: An objective evaluation of patient compliance. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 1994;149:149–54. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.1.8111574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Donnell AR, Bjornson CL, Bohn SG, Kirk VG. Compliance rates in children using noninvasive continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep. 2006;29:651–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engleman HM, Asgari-Jirandeh N, McLeod AL, Ramsay CF, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Self-reported use of CPAP and benefits of CPAP therapy. Chest. 1996;109:1470–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.6.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauscher H, Formanek D, Popp W, Zwick H. Self-reported vs. measured compliance with nasal CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1987;103:1675–80. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.6.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *10.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2009;5:263–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]