Abstract

Candida glabrata owes its success as a pathogen, in part, to a large repertoire of adhesins present on the cell surface. Our current knowledge of C. glabrata adhesins and their role in the interaction between host and pathogen is limited to work with only a single family of epithelial adhesins (Epa proteins). Here we report identification and characterization of a family of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored cell wall proteins in C. glabrata. These proteins are absent in both S. cerevisiae and C. albicans suggesting that C. glabrata has evolved different mechanism(s) for interaction with host cells. In the current study we present data on the characterization of Pwp7p (PA14 domain containing Wall Protein) and Aed1p (Adherence to Endothelial cells) of this family in the interaction of C. glabrata with Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs). Deletion of C. glabrata genes PWP7 and AED1 results in significant reduction in adherence to endothelial cells compared to the wild type parent. These data indicate that C. glabrata utilizes these proteins for adherence to endothelial cells in vitro. This also represents the first evidence that C. glabrata utilizes adhesins other than Epa proteins.

Keywords: Candida, GPI, adhesin, PWP7, AED1, AED2

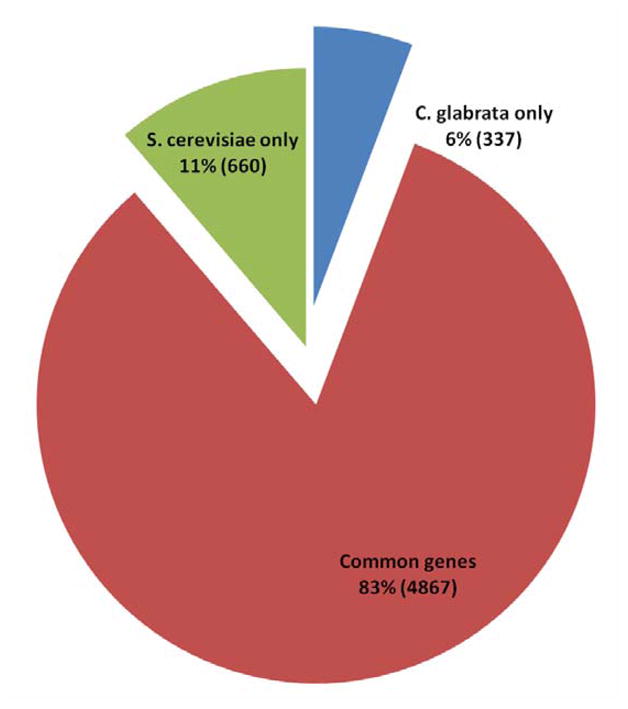

Candida glabrata, a commensal of humans, is the second most common cause of fungal infections in humans after Candida albicans and is responsible for about 20 – 24 % of all Candida blood stream infections (BSI) in the United States (Pfaller & Diekema, 2007). Despite being classified in the same genus, C. glabrata and C. albicans are quite distinct and the former is much more closely related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, suggesting that the interactions of these two Candida species with their mammalian host may have evolved independently. C. glabrata is also a serious clinical problem because it is innately less susceptible to the azole class of antifungal drug used for treating patients. The two most prominent differences between C. glabrata and C. albicans, other than the ploidy, are the inability of the former species to form true hyphae and to secrete certain proteinases (e.g. secreted aspartyl proteinases, etc.). These two key features have been reported to play a very prominent role in C. albicans virulence (Calderone & Fonzi, 2001). Because C. glabrata lacks both these factors it is unclear how it colonizes host tissue and causes disease. Research with bacterial pathogens has revealed that they differ from non pathogenic species in a variety of ways. One of the most prominent differences is in the gene content. Bacterial pathogens often carry chromosomal gene clusters, also termed “pathogenicity islands” that encode several virulence related traits. These “pathogenicity islands” are absent from related non pathogenic species. We therefore hypothesized that a genome wide comparison of C. glabrata with its non-pathogenic relative S. cerevisiae might provide clues to virulence mechanisms of this organism. Genes that are not shared by the two species may explain the differences in virulence and pathogenesis of these two organisms. Of particular interest are the genes that are unique to C. glabrata. Our genome wide comparison has revealed that although a majority of C. glabrata genes have orthologues in S. cerevisiae, interestingly, about 6% which accounts for approximately 337 genes are not represented in S. cerevisiae (Figure 1). From this set of 337 genes which are unique to C. glabrata and are absent in S. cerevisiae we have identified a novel family of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored proteins (Table 1). We hypothesize that these proteins are adhesins that participate in host-pathogen interactions and pathogenesis of C. glabrata.

Figure 1.

Comparative genomic analysis of S. cerevisiae and C. glabrata.

Table 1.

List of genes and their putative function in family GL3M4601.

| Gene family | Protein coding genes | Putative function |

|---|---|---|

| GL3M4601 | CAGL0C00253g | 1608 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. |

| CAGL0C00968g | 1034 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0C01133g | 1036 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0E00231g | 1864 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0E01661g | 1415 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0G10219g | 992 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0H10626g | 1326 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0I10098g (PWP7) | 1618 aa. PA14 domain GPI-anchored cell surface glycoprotein. Required for adherence to endothelial cells. | |

| CAGL0I10197g (PWP1) | 1373 aa. PA 14 domain. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0I10246g (PWP8) | 1240 aa. PA14 domain. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0I10340g (PWP5) | 1012 aa. PA14 domain. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0I10362g (PWP4) | 1772 aa. PA14 domain. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0J05170g | 1529 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0K00110g | 832 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0K13002g (AED2) | 937 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored. | |

| CAGL0K13024g (AED1) | 1075 aa. GPI-anchored cell surface glycoprotein. Required for adherence to endothelial cells. | |

| CAGL0L00157g | 1731 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0L09911g | 1451 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0L10092g | 1416 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0L13310g | 1630 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. | |

| CAGL0L13332g | 1035 aa. No known domains. GPI anchored, putative adhesin. |

Adhesins involved in adherence to host tissue are critical for colonization leading to invasion and damage to host tissue, yet very few adhesins have been identified from fungal pathogens. There are significant gaps in our knowledge of C. glabrata adhesins and their role in the interaction between host and pathogen. To date, only a single family of epithelial adhesins (Epa proteins) has been functionally characterized in this species, and we believe other adhesins are involved, as discussed later in this manuscript. Thus, identification of new adhesins is essential to understand C. glabrata virulence mechanisms. Adherence of C. glabrata to epithelial cells is shown to be mediated, in part, by the proteins of EPA gene family (Cormack et al., 1999; Domergue et al., 2005; Frieman et al., 2002; Kaur et al., 2005; Kaur et al., 2007). Previous work has shown that C. glabrata possesses a much larger number of putative adhesins in its genome (De Groot et al., 2008; Weig et al., 2004). Genes encoding putative adhesins are classified in seven different subfamilies (I – VII) based on their N-terminal domain sequence similarity (De Groot et al., 2008). The EPA gene family constitutes subfamily I. The genes listed in the family GL3M4601, identified by us, are scattered in subfamilies II, III, V and VII, suggesting that the ligand binding domains of proteins encoded by this gene family may have varied substrate specificity. Two genes included in this family CAGL0L13310g and CAGL0L13332g belong to subfamily I, thus becoming part of the EPA family. Function of these two genes is currently unknown as they are not yet characterized. The subfamily II has all of the genes coding for proteins containing the PA14 domain and were appropriately named PA14 domain containing wall proteins.

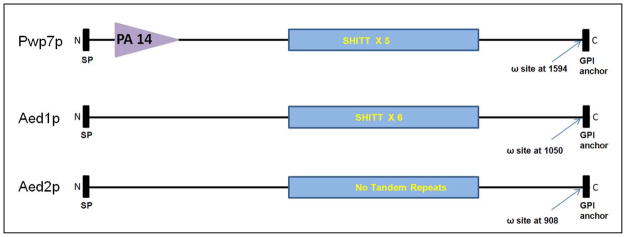

In this study we present data on the in vitro characterization of Pwp7p (PA14 domain containing Wall Protein), Aed1p (Adherence to Endothelial cells) and Aed2p of this family. Aed1p and Aed2p are listed in subfamily III. Because of its evident function in adherence to endothelial cells we named this gene AED1 (adherence to endothelial cells). Preliminary sequence analysis of Pwp7p (CAGL0I10098g) shows that this protein consists of 1618 amino acid residues and has a conserved PA14 (anthrax Protective Antigen) domain, found in yeast adhesins, along with a predicted signal peptide sequence at the N- terminus and a GPI anchor signal sequence at the C-terminus. A predicted ω site, the cleavage site for addition of the GPI anchor, is present at amino acid 1594. Aed1p (CAGL0K13024g) and Aed2p (CAGL0K13002g) consist of 1075 and 937 amino acids respectively. Both the proteins have similar GPI anchor protein architecture as Pwp7p except that the PA14 domain is missing in both Aed1p and Aed2p (Figure. 2). A Predicted ω site is present in both Aed1p and Aed2p at 1050 and 908 amino acids respectively. A long term goal of the present study is to elucidate the molecular mechanism of Pwp7p and Aed1p adhesins as it relates to pathogenesis and virulence of C. glabrata. We anticipate that the results of these studies will increase our knowledge of this very important class of proteins and their role in virulence of this pathogen and also provide the foundation for the future development of novel therapeutic approaches.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation (size not to scale) of Pwp7p (1618 amino acids), Aed1p (1075 amino acids) and Aed2p depicting N-terminal signal peptide (SP), C-terminus GPI anchor, ω site, a conserved PA14 domain and “SHITT” repeat sequences. The PA14 domain prediction was done by using SMART. GPI anchor prediction was performed by using GPI-SOM (http://gpi.unibe.ch/) and PredGPI (http://gpcr2.biocomp.unibo.it/gpipe/pred.htm) software.

The C. glabrata strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Tables 2 and 3. All Candida strains were maintained as frozen stocks and grown on YPD agar (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose and 2% agar). The C. glabrata strains were grown routinely in liquid YPD medium at 30°C in an incubator shaker overnight prior to use in the experiments. The plasmid pAP599 (Kaur et al., 2007) used to create deletion mutant strains was provided by Brendan Cormack, Johns Hopkins University, MD. For adherence assays, overnight cultures of C. glabrata cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline and enumerated with a hemacytometer, prior to use.

Table 2.

List of strains used in the present study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| NEB Turbo competent E. coli (K12 strain derivative) | F′ proA+B+ lacIq Δ lacZ M15/fhuA2 Δ(lac- proAB) glnV gal R(zgb-210::Tn10)TetS endA1 thi-1 Δ(hsdS-mcrB)5 | NEB |

| NEB Express competent E. coli (BL21 strain derivative) | fhuA2 [lon] ompT gal sulA11 R(mcr-73::miniTn10--TetS)2 [dcm] R(zgb-210::Tn10--TetS) endA1 Δ(mcrC-mrr)114::IS10 | NEB |

| BG14 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418r; wt Ura− | 16 |

| Δpwp7 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418r pwp7Δ::hph Hygr | This Study |

| R-PWP7-Re-integrant | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418r pwp7+::hph Hygr, pRC-PWP7 | This Study |

| Δaed1 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418r aed1Δ::hph Hygr | This Study |

| R-AED1-Re-integrant | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418r k8+::hph Hygr, pRC-AED1 | This Study |

| Δaed2 | ura3Δ::Tn903 G418r aed2Δ::hph Hygr | This Study |

Table 3.

List of plasmids used in the present study

| Plasmid | Description/genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pGEM-T | Cloning vector with Apr and lacZ markers, f1 ori and T7/SP6 RNA polymerase promoters | Promega |

| pAP599 | Cloning vector with 2 FRT direct repeats flanking the hygromycin marker [FRT-PPGK::hph::(3′ UTR of HIS3)-FRT] for construction of multiple mutants; URA3 Hygr Apr markers | 19 |

| pGRB 2.1 | Episomal plasmid vector containing ScURA3 marker, Apr, ScCEN and ARS sequences and a pBS polylinker into which the promoter and ORFs of PWP7 and AED1 were cloned for strain reconstitution | 18 |

| pKC-PWP7 | Knock-out construct in which a 684bp KpnI/HindIII PCR fragment carrying 5′-UTR with the promoter region of PWP7 and a 740bp SpeI/SacI PCR fragment carrying the 3′ UTR region of PWP7 gene were cloned flanking the hygromycin marker into pAP599 | This study |

| pKC-AED1 | Knock-out construct in which a 629bp KpnI/HindIII PCR fragment carrying 5′-UTR with the promoter region of K8 and a 512bp SpeI/SacI PCR fragment carrying the 3′ UTR region of AED1 gene were cloned flanking the hygromycin marker into pAP599 | This study |

| pKC-AED2 | Knock-out construct in which a 758bp KpnI/HindIII PCR fragment carrying 5′-UTR with the promoter region of PWP7 and a 562bp BamHI/SpeI PCR fragment carrying the 3′ UTR region of AED2 gene were cloned flanking the hygromycin marker into pAP599 | This study |

| pRC-PWP7 | A strain reconstitution plasmid construct in which a 946bp PCR fragment carrying promoter region and a 4.9 Kb PCR fragment carrying the complete ORF of PWP7 were cloned into pGRB2.1 vector | This study |

| pRC-AED1 | A strain reconstitution plasmid construct in which a 4.3 Kb PCR fragment carrying promoter region and the complete ORF of AED1 were cloned into pGRB2.1 vector | This study |

One striking feature of both PWP7 and AED1 is that they harbor very large intragenic tandem repeat sequences with motif size ranging from 132 to 195 nucleotides. Both Pwp7p and Aed1p contain conserved “SHITT” repeat sequences and this motif is repeated 5 and 6 times in Pwp7 and Aed1p respectively (Figure 2). The size of each tandem repeats is different in both PWP7 (195 nucleotides each repeat) and AED1 (132 nucleotides each repeat). There are no “SHITT” tandem repeats in Aed2p. Because of their size, these tandem repeat sequences were given the name “megasatellites” and are reported to be present only in C. glabrata and its closest yeast relative Kluyveromyces delphensis (Rolland et al., 2010; Thierry et al., 2008). Interestingly, these repeat sequences are found only in genes encoding for cell wall proteins, suggesting that they may have a role in adherence and pathogenicity (Thierry et al., 2008; Thierry et al., 2010). We believe that this is the first report of functional characterization of the C. glabrata gene(s) carrying megasatellites.

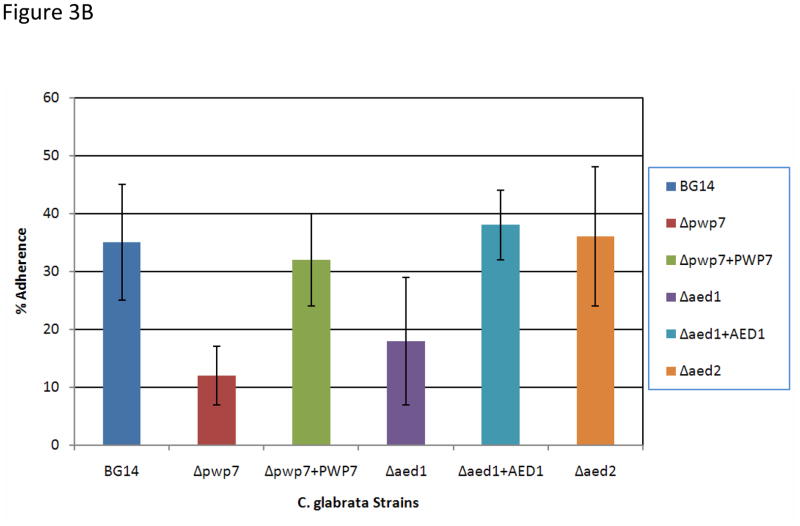

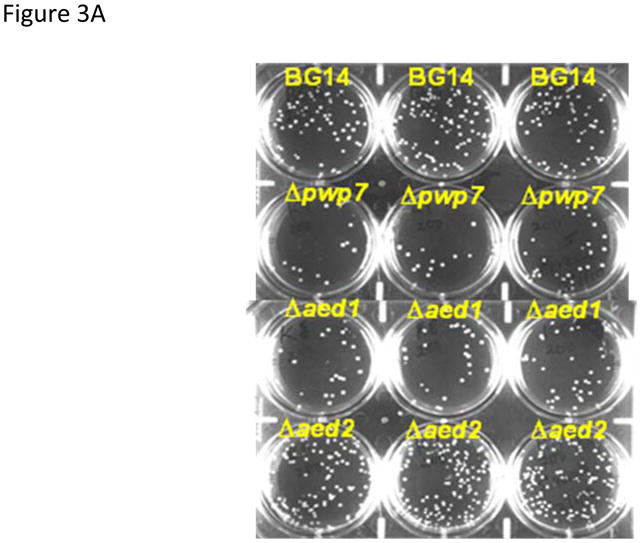

To test our hypothesis that both PWP7 and AED1 encode adhesins and mediate adherence to endothelial cells we performed adherence assays using a previously described protocol (Klotz et al., 1983; Rotrosen et al., 1985). Adherence of C. glabrata BG14 (wild-type) and null-mutant strains to endothelial cells was measured (Figure. 3A). The percent adherence observed for the wild-type BG14 strain was 35%, whereas only 12% Δpwp7 and 18% Δaed1 mutant cells were adherent to endothelial cells resulting in 66% and 50% reduction in adherence respectively, compared to wild type. The gene reconstituted strains pwp7+PWP7 and aed1+AED1 had wild type levels of adherence (Figure 3B). These data clearly indicate that PWP7 and AED1 encode functional adhesins and C. glabrata utilizes these proteins for its adherence to endothelial cells in vitro. This also represents the first evidence that C. glabrata utilizes adhesins other than Epa proteins. We did not observe any decrease in adherence of the Δaed2 null mutant compared to wild type (Figure 3). This may be due to functional redundancy as well as compensatory mechanisms leading to up-regulation of similar adhesins in vivo. Since Δaed2 mutant had no observable phenotype in vitro, the current manuscript is focused on characterization of Pwp7p and Aed1p.

Figure 3.

Adherence of C. glabrata strains to endothelial cells (A) adherence assays were performed in 6 well tissue culture plates. The Δpwp7 and Δaed1 mutants are less adherent to endothelial cells compared to wild type strain BG14. The Δaed2 mutant has redundant function in C. glabrata interaction with endothelial cells. (B) Quantification of adherence assay. Results are average ± SD of three biological replicates each measured in triplicate.

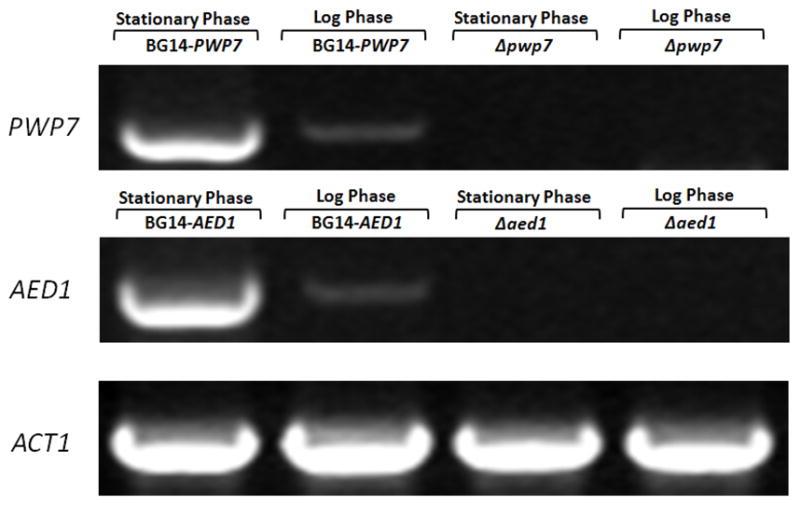

To determine whether the wild-type PWP7 and AED1 are transcriptionally silenced RT-PCR assays were performed (Chauhan et al., 2003). Primers used to perform RT-PCR are listed in table 4. Our data indicate that both PWP7 and AED1 are not regulated by transcriptional silencing. Genes encoding Pwp7p and Aed1p appear to be expressed more in stationary growth phase compared to logarithmic growth phase (Figure. 4). We have observed that stationary phase cultures are more adherent to endothelial cells compared to log phase grown cells perhaps due to increased expression of these genes in stationary phase. This is consistent with our hypothesis that these proteins play a major role in C. glabrata adhesion. However, our observation of stationary phase C. glabrata being more adherent to endothelial cells is in contrast to a previous report by Castano et al (2005) where they reported that log phase C. glabrata cells were more adherent to epithelial cells, it was attributed due to greater expression of EPA1 in logarithmic growth phase. This discrepancy in results may be due to different cell type (epithelial vs. endothelial) used in the adherence assays. In a report by De Groot et al. (2008) C. glabrata strain ATCC 2001 was also shown to be more adherent in stationary growth phase.

Table 4.

List of primers used for RT-PCR in the present study.

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| PWP7-RT-ORF-F | TTCCGTGGTTACTTCATCCCACCA |

| PWP7-RT-ORF-R | AGAACCAGAACCACCTTCACCAGT |

| AED1-RT-ORF-F | TGCTTGGGTACTTTCGTGGAGTGT |

| AED1-RT-ORF-R | ATGCCGATCGCTGTAATAGGTAGC |

| AED2-RT-ORF-F | AGGATCCTGACGCAATGAGGCTTA |

| AED2-RT-ORF-R | ACTTGCTGGAAAGCGAGGGAGTAT |

| ACTIN-RT-F | TCGGTGACGAAGCTCAATCCAAGA |

| ACTIN-RT-R | CAATGGATGGACCACTTTCGTCGT |

Figure 4.

Transcript levels of PWP7 and AED1 by RT-PCR analysis. For each experiment, β-actin was used as internal control. RT-PCR gels were scanned and images were stored as TIFF files. Results were similar for three independent analyses of each gene. A represented RT-PCR gel image is shown.

The only functionally characterized C. glabrata adhesins (Epa family) have been shown to undergo transcriptional silencing (Castano et al., 2005). It has also been reported that in organisms such as Trypanosoma cruzi and Plasmodium falciparum certain cell surface genes coding for adhesins are either regulated by transcriptional silencing or by epigenetic mechanisms adding to cell surface variability (Baruch et al., 1995; Bull et al., 2005; Buscaglia et al., 2006). To determine the transcript levels and to find out whether remaining nineteen genes of this family are subjected to transcriptional silencing, we performed RT-PCR analysis as described earlier. Our results indicate that four genes of this family: CAGL0C00253g, CAGL0H10626g, CAGL0L09911g and CAGL0L00157g were transcriptionally silent (data not shown).

Fungal adhesins have been recognized as major virulence factors that contribute to pathogenesis of these organisms (Bernhardt et al., 2001; Cormack et al., 1999; Hoyer, 2001; Sundstrom, 2002; Verstrepen & Klis, 2006). Adherence of microorganisms to host tissue is considered a prerequisite for tissue invasion and infection. Adhesion is usually initiated by binding of cell surface adhesins to specific ligands (amino acid or sugar residues) on the surface of other cells or by promoting binding to abiotic inert surfaces. The major adhesins studied in C. albicans so far are HWP1 (Staab et al., 1999), EAP1 (Li & Palecek, 2003) and members of ALS gene family (Hoyer, 2001). HWP1 and ALS family members have been implicated in virulence apart from their roles in adhesion to different host cell as well as abiotic surfaces (Sharkey et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2004). EAP1 has been shown to contribute to adherence to polystyrene and biofilm formation (Li et al., 2007), but its role in pathogenesis is yet to be determined. The Epa proteins remain the only functionally characterized adhesins from C. glabrata thus far. As the name suggests, these proteins are responsible for adherence to host epithelial cells. More recently Zupancic et al (2008) showed that Epa1p and Epa7p also contribute to adherence to endothelial cells. The contribution of Epa proteins in C. glabrata virulence has also been studied. In a mouse model of disseminated candidiasis an epa1 mutant showed no significant reduction of virulence compared to wild type (Cormack et al., 1999). However deletion of the EPA1-3 cluster leads to partial attenuation in virulence of C. glabrata (De Las Penas et al., 2003). The expression of normally silent EPA6 is induced in a mouse model of urinary tract infection highlighting the important role played by adhesins in infection process (Domergue et al., 2005). Based on these data, clearly there is an urgent need to characterize other adhesins in C. glabrata to gain a better understanding of their biological roles in virulence, biofilm formation and adhesion to host cells.

In conclusion, we report here identification of a family of adhesins in C. glabrata by in silico comparison of S. cerevisiae and C. glabrata. As stated earlier there are twenty one genes in this family predicted to be cell surface GPI anchored proteins. In this manuscript we present data on characterization of Pwp7p and Aed1p by making gene deletion knock out mutants. C. glabrata is the second most commonly isolated Candida species from blood of infected patients after C. albicans, yet C. glabrata interactions with endothelial cells are poorly understood. C. albicans damages human vascular endothelial cells both in vitro and in vivo (Filler et al., 1995; Belanger et al., 2002). In a screen for mutants defective in damage to endothelial cell, Sanchez et al (2004) reported that C. albicans mutants, which caused less damage to endothelial cells, were also less virulent in a mouse model of disseminated candidiasis. Little is known about how C. glabrata crosses the endothelial barrier to cause invasive disease. The mechanism of hematogenous dissemination of C. glabrata is also poorly understood. We have made an attempt to identify adhesins specific for C. glabrata interaction with endothelial cells. Our results demonstrate that both Pwp7p and Aed1p are adhesins and are required for C. glabrata adherence to endothelial cells in vitro. The work presented herein provides a foundation for future studies to dissect molecular mechanism(s) by which C. glabrata adhesins contribute to disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by NIH-NIAID grant 5R21AI 076084-03 and an American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grant 0635108N to NC. Authors are thankful to Brendan Cormack, Johns Hopkins University for his generous gift of pAP599 and pGRB2.1 plasmid vectors & wild-type C. glabrata BG14 strain for this work. We would like to thank Genolevures consortium for help with comparative genomic analysis.

References

- 1.Baruch DI, Pasloske BL, Singh HB, et al. Cloning the P. falciparum gene encoding PfEMP1, a malarial variant antigen and adherence receptor on the surface of parasitized human erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belanger PH, Johnston DA, Fratti RA, Zhang M, Filler SG. Endocytosis of Candida albicans by vascular endothelial cells is associated with tyrosine phosphorylation of specific host cell proteins. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:805–812. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernhardt J, Herman D, Sheridan M, Calderone R. Adherence and invasion studies of Candida albicans strains, using in vitro models of esophageal candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1170–1175. doi: 10.1086/323807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bull PC, Berriman M, Kyes S, et al. Plasmodium falciparum variant surface antigen expression patterns during malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buscaglia CA, Campo VA, Frasch AC, Di Noia JM. Trypanosoma cruzi surface mucins: host-dependent coat diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:229–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calderone RA, Fonzi WA. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:327–335. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castano I, Pan SJ, Zupancic M, Hennequin C, Dujon B, Cormack BP. Telomere length control and transcriptional regulation of subtelomeric adhesins in Candida glabrata. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1246–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chauhan N, Inglis D, Roman E, Pla J, Li D, Calera JA, Calderone R. Candida albicans response regulator gene SSK1 regulates a subset of genes whose functions are associated with cell wall biosynthesis and adaptation to oxidative stress. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:1018–1024. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.5.1018-1024.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cormack BP, Ghori N, Falkow S. An adhesin of the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata mediating adherence to human epithelial cells. Science. 1999;285:578–582. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Groot PW, Kraneveld EA, Yin QY, et al. The cell wall of the human pathogen Candida glabrata: differential incorporation of novel adhesin-like wall proteins. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1951–1964. doi: 10.1128/EC.00284-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Las Penas A, Pan SJ, Castano I, Alder J, Cregg R, Cormack BP. Virulence-related surface glycoproteins in the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata are encoded in subtelomeric clusters and subject to RAP1- and SIR-dependent transcriptional silencing. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2245–2258. doi: 10.1101/gad.1121003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domergue R, Castano I, De Las Penas A, et al. Nicotinic acid limitation regulates silencing of Candida adhesins during UTI. Science. 2005;308:866–870. doi: 10.1126/science.1108640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filler SG, Swerdloff JN, Hobbs C, Luckett PM. Penetration and damage of endothelial cells by Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:976–983. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.976-983.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frieman MB, McCaffery JM, Cormack BP. Modular domain structure in the Candida glabrata adhesin Epa1p, a beta1,6 glucan-cross-linked cell wall protein. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:479–492. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu Y, Ibrahim AS, Sheppard DC, et al. Candida albicans Als1p: an adhesin that is a downstream effector of the EFG1 filamentation pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:61–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoyer LL. The ALS gene family of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:176–180. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)01984-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur R, Ma B, Cormack BP. A family of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked aspartyl proteases is required for virulence of Candida glabrata. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7628–7633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611195104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur R, Domergue R, Zupancic ML, Cormack BP. A yeast by any other name: Candida glabrata and its interaction with the host. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klotz SA, Drutz DJ, Harrison JL, Huppert M. Adherence and penetration of vascular endothelium by Candida yeasts. Infect Immun. 1983;42:374–384. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.374-384.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li F, Palecek SP. EAP1, a Candida albicans gene involved in binding human epithelial cells. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:1266–1273. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.6.1266-1273.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li F, Svarovsky MJ, Karlsson AJ, et al. Eap1p, an adhesin that mediates Candida albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:931–939. doi: 10.1128/EC.00049-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rolland T, Dujon B, Richard GF. Dynamic evolution of megasatellites in yeasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4731–4739. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotrosen D, Edwards JE, Jr, Gibson TR, Moore JC, Cohen AH, Green I. Adherence of Candida to cultured vascular endothelial cells: mechanisms of attachment and endothelial cell penetration. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:1264–1274. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez AA, Johnston DA, Myers C, Edwards JE, Jr, Mitchell AP, Filler SG. Relationship between Candida albicans virulence during experimental hematogenously disseminated infection and endothelial cell damage in vitro. Infect Immun. 2004;72:598–601. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.598-601.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharkey LL, Liao WL, Ghosh AK, Fonzi WA. Flanking direct repeats of hisG alter URA3 marker expression at the HWP1 locus of Candida albicans. Microbiology. 2005;151:1061–1071. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staab JF, Bradway SD, Fidel PL, Sundstrom P. Adhesive and mammalian transglutaminase substrate properties of Candida albicans Hwp1. Science. 1999;283:1535–1538. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundstrom P. Adhesion in Candida spp. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:461–469. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thierry A, Dujon B, Richard GF. Megasatellites: a new class of large tandem repeats discovered in the pathogenic yeast Candida glabrata. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:671–676. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0216-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thierry A, Bouchier C, Dujon B, Richard GF. Megasatellites: a peculiar class of giant minisatellites in genes involved in cell adhesion and pathogenicity in Candida glabrata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5970–5982. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verstrepen KJ, Klis FM. Flocculation, adhesion and biofilm formation in yeasts. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:5–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weig M, Jansch L, Gross U, De Koster CG, Klis FM, De Groot PW. Systematic identification in silico of covalently bound cell wall proteins and analysis of protein-polysaccharide linkages of the human pathogen Candida glabrata. Microbiology. 2004;150:3129–3144. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao X, Oh SH, Cheng G, et al. ALS3 and ALS8 represent a single locus that encodes a Candida albicans adhesin; functional comparisons between Als3p and Als1p. Microbiology. 2004;150:2415–2428. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26943-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zupancic ML, Frieman M, Smith D, Alvarez RA, Cummings RD, Cormack BP. Glycan microarray analysis of Candida glabrata adhesin ligand specificity. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:547–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.