Abstract

The purpose of this study was to compare force variability and the neural activation of the agonist muscle during constant isometric contractions at different force levels when the amplitude of respiration and visual feedback were varied. Twenty young adults (20–32 years, 10 men and 10 women) were instructed to accurately match a target force at 15 and 50% of their maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) with abduction of the index finger while controlling their respiration at different amplitudes (85, 100 and 125% normal) in the presence and absence of visual feedback. Each trial lasted 22 s and visual feedback was removed from 8–12 to 16–20 s. Each subject performed 3 trials with each respiratory condition at each force level. Force variability was quantified as the standard deviation of the detrended force data. The neural activation of the first dorsal interosseus (FDI) was measured with bipolar surface electrodes placed distal to the innervation zone. Relative to normal respiration, force variability increased significantly only during high-amplitude respiration (~63%). The increase in force variability from normal- to high-amplitude respiration was strongly associated with amplified force oscillations from 0–3 Hz (R2 ranged from .68 – .84; p < .001). Furthermore, the increase in force variability was exacerbated in the presence of visual feedback at 50% MVC (vision vs. no-vision: .97 vs. .87 N) and was strongly associated with amplified force oscillations from 0–1 Hz (R2 = .82) and weakly associated with greater power from 12–30 Hz (R2 = .24) in the EMG of the agonist muscle. Our findings demonstrate that high-amplitude respiration and visual feedback of force interact and amplify force variability in young adults during moderate levels of effort.

1. Introduction

Maintaining a constant force output with the fingers is essential in various manual tasks of daily living (e.g., writing, threading a needle or holding a fragile object), artistic work, and microsurgical operations. Nonetheless, there is an inherent and involuntary variation in force output which can be detrimental to task precision. The amplitude in the variability of force, therefore, is frequently used as a metric of force control. In addition to its functional relevance, the simplicity of maintaining a constant force output is often an attractive laboratory task to compare young and older adults (Christou & Tracy, 2005; Enoka et al., 2003) as well as patients with central nervous system disorders with age-matched controls (Vaillancourt, Slifkin, & Newell, 2001a, 2001b).

The variability of force can be influenced by numerous factors including the force level (Christou, Grossman, & Carlton 2002), age of the subject (Enoka et al., 2003), fatigue (Hunter, Critchlow, Shin, & Enoka, 2004), stress (Christou, 2005; Christou, Jakobi, Critchlow, Fleshner, & Enoka, 2004), and visual feedback (Baweja, Patel, Martinkewiz, Vu, & Christou, 2009; Baweja, Kennedy, Vu, Vaillancourt, & Christou, 2010; Sosnoff & Newell, 2006; Tracy, Dinenno, Jorgensen, & Welsh, 2007). Recently, respiration has also been implicated with influencing the amplitude of force variability during constant isometric contractions (Li & Yasuda, 2007; Turner & Jackson 2002). The interaction between the respiratory and motor systems has been shown previously primarily for rhythmical tasks (Ebert, Rassler, & Hefter, 2000; Rassler & Kohl, 2000; Rassler, Nietzold, & Waurick, 1999). The literature related to the influence of respiration on voluntary motor control, however, is minimal. For example, subjects appear to be better at tracing targets with the finger during mid-inspiration and mid-expiration compared with respiratory phase transitions (Rassler et al., 1999). Also, there is evidence that respiration is adjusted in anticipatory fashion based on the control demands of the manual task (Lamberg, Mateika, Cherry, & Gordon, 2003; Rassler, Bradl, & Scholle, 2000).

In terms of the effects of respiration on force control during constant isometric contractions the literature is limited. For example, there is evidence that expiration against resistive respiration can amplify force variability during isometric contractions with the knee extensors (Turner & Jackson, 2002). Furthermore, a recent study by Li and Yasuda (2007) demonstrated that forced inspiration and expiration amplified force variability during constant isometric contractions with flexion of the index finger. Finally, there is indirect evidence that respiration can potentially influence force variability. Specifically, most of the power in a force signal during constant isometric contractions occurs from 0–1 Hz (Christou, 2005; Slifkin, Vaillancourt, & Newell, 2000) and the peak power occurs at ~ 0.25 Hz. The normal respiratory cycle lasts ~4 seconds (~0.25 Hz; (Rassler et al., 2000)) and thus respiration may contribute to the peak power in the force spectrum. Based on these three pieces of evidence, therefore, it is possible that respiration could potentially influence force variability during constant isometric contractions.

Nonetheless, the conclusions that can be drawn from the studies by Turner and Jackson (2002) and Li and Yasuda (2007) on force variability during constant isometric contractions are limited for the following reasons: (1) The neural activation of the involved muscles was not examined with the respiratory intervention, and thus it is not clear whether the respiration effects on force variability were due to neural changes of the agonist muscles. (2) The interactive effects of respiration with other important factors that contribute to force variability, such as visual feedback, have not been examined. For example, changes in the variability of force output with respiration may be minimal but amplified with visuomotor corrections. (3) Finally, the findings by Li and Yasuda (2007) may have been influenced by dual tasking. Forced inspiration and expiration (rhythmical tasks) may be more demanding cognitively than the Valsalva maneuver. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to compare force variability and the neural activation of the agonist muscle during constant isometric contractions when the amplitude of respiration and visual feedback was varied. Part of the findings have been reported in abstract form (Neto, Marzullo, Baweja, & Christou, 2009).

2. Methods

Participants

Twenty young adults (aged 20–32 years, 10 men and 10 women) volunteered to participate in this study. All subjects reported being healthy without any known neurological problems, were right-handed according to a standardized survey (Oldfield, 1971), and had normal or corrected vision. The Institutional Review Board at the Texas A&M University approved the procedures, and subjects provided written informed consent before participation in the study.

Experimental arrangement

Each subject was seated comfortably in an upright position facing a 22 inch computer screen (NEC MultiSync LCD 2180 UX, NEC Display Solutions, IL, USA) that was located 1 m away at eye level. The monitor was used to display the force produced by the abduction of the index finger. All subjects affirmed that they could see the display clearly. The average visual angle for the force task was ~0.3°. The left arm was abducted by 45° and flexed to ~90° at the elbow. The left forearm was pronated and secured in a specialized padding (Versa form™, AB Germa, Sweden). The thumb, middle, ring, and fifth fingers of the left hand were restrained with metal plates and there was approximately a right angle between the index finger and thumb. Only the left index finger was free to move. The left index finger was placed in an adjustable finger orthosis to maintain extension of the middle and distal interphalangeal joints and was abducted 5° from the neutral position (for a schematic see Taylor et al. 2003). The left hand (non-dominant) was used so the results could be compared with previous studies (Enoka et al., 2003). This arrangement allowed abduction of the index finger about the metacarpophalangeal joint in the horizontal plane, a movement produced almost exclusively by contraction of the first dorsal interosseus (FDI) muscle (Chao et al., 1989; Li, Pfaeffle, Sotereanos, Goitz, & Woo, 2003).

Respiration measurement

The respiratory airflow during the experiment was monitored using a nasal/oral respiration transducer (Model 1401G, Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI, USA). The respiration signal was sampled at 1 kHz with a Power 1401 A/D board (Cambridge Electronic Design, UK) and stored on a personal computer.

Force measurement

The constant isometric force produced by the abduction of the index finger was recorded with a three dimensional force transducer (JR3 Multi-Axis Force-Torque Sensor System, JR3 Inc., CA). The subjects attempted to control the force exerted perpendicular to the force transducer (abduction force) and feedback was provided only for this force direction. The other two force directions recorded were the vertical direction to the force transducer (flexion-extension movement of the index finger) and anterior-posterior to the force transducer (anterior-posterior movement of the index finger). The focus of this study was the control of force exerted perpendicular to the force transducer (abduction force) and thus the other two force directions will be ignored. The force signal was sampled at 1 kHz with a Power 1401 A/D board (Cambridge Electronic Design, UK) and stored on a personal computer.

EMG measurement

Abduction of the index finger, as arranged in this experimental setup, is produced almost exclusively by the contraction of the FDI muscle (Chao et al., 1989; Li et al., 2003). The FDI muscle activity was recorded with 2 pairs of gold disc electrodes (4 mm diameter, model F-E6GH, Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI, USA) and taped on the skin distally to the innervation zone (Homma & Sakai, 1991). The recording electrodes were placed in line with the muscle fibers. The center-to-center distance between the two electrodes was 5 mm. The reference electrode was placed over the ulnar styloid. The EMG signal was amplified (× 2000) and band pass filtered at 3–1000 Hz (Grass Model 15LT system; Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI, USA). The EMG signal was sampled at 2 kHz with a Power 1401 A/D board (Cambridge Electronic Design, UK) and stored on a personal computer.

MVC task

Subjects were instructed to increase the force from baseline to maximum over a 2 s period and maintain the maximal force for about 4 s. Five such recordings were made or until two of the maximal trials were within 5% of each other. The maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) force was quantified as the average force over 3 s (constant part) of the highest trial.

Constant isometric force task

A custom-written program in Matlab® (Math Works™ Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA) manipulated the targeted force level and visual feedback condition (presence or absence of visual feedback). The gain of visual feedback remained constant at 12.8 pixels/N (visual angle was ~0.3°). The target force was provided as a red horizontal line in the middle of the monitor and the force exerted by the subjects as a blue line progressing with time from left to right. In random order, each subject was presented with two constant force targets at 15% and 50% MVC. The subjects were instructed to gradually push against the force transducer and increase their force to match the red line (target force) within 3 s. When the target was reached, subjects were instructed to maintain their force (blue line) on the target (red line) as accurate and as consistently as possible. The whole trial lasted 22 s and visual feedback was removed from 8–12 s and 16–20 s (black bars, Fig. 1 A). Subjects performed three trials at every force level. Within each force level (blocked) the rest time between each trial was 15 s. The rest time between force levels was 3 minutes. The order for the force conditions was counterbalanced among subjects.

Fig. 1.

A) Constant isometric force task with the FDI muscle. Representative trial from 1 subject when exerting a constant force at 15% MVC with a visual angle of ~0.3°. Each subject was instructed to exert a force with abduction of the index finger against a force transducer and match the horizontal target line for 22 seconds. Visual feedback of the target line (red line) and exerted force (black trace) was given to the subjects from 0–8 s and 12–16 s (visual feedback condition), whereas visual feedback of the target and exerted force was removed (black bars) from 8–12 s and 16–20 s (no visual feedback condition). B) Respiration training: subjects were instructed to do the following: (a) control their respiration rate by inhaling through their nose with the same rate the horizontal bar was becoming red (dark grey) from left to right and exhaling through their mouth when the horizontal bar was becoming green (light grey) from right to left; (b) control their inhalation amplitude by inhaling through their nose and matching the target on the top vertical bar that was becoming red from bottom to top (towards the targeted line); (c) control their exhalation amplitude by exhaling through their mouth and matching the target on the bottom vertical bar that was becoming green from bottom to top (towards the targeted line).

Experimental protocol

During the first hour of testing, subjects performed the MVC trials and constant isometric contractions from 2–70% under different visual feedback conditions. Respiration was not mentioned to the subjects and thus they performed these contractions using their normal respiration patterns. At the end of these contractions another set of MVC trials was recorded. Following these set of contractions and based on their normal respiratory patterns (Normal-amplitude respiration; 100%) at 15 and 50% MVC (same pattern) we calculated 75% and 150% of their normal respiratory amplitude. Based on these numbers we created the following 2 respiratory conditions: (1) High-amplitude respiration (100% rate and 150% amplitude); (2) Low-amplitude (100% rate and 75% amplitude). Prior to the performance of the force task with each of the above respiratory conditions subjects practiced the respiratory conditions (Fig. 1B). The training of each of the conditions included feedback of their respiratory amplitude and rate relative to a target. The feedback was given on the monitor that was located in front of them in the form of a horizontal bar and two vertical bars, one located on the top and the other at the bottom of the horizontal bar (Fig. 1B). Specifically, subjects were instructed to do the following: (1) control their respiratory rate by inhaling through their nose with the same rate the horizontal bar (Fig. 1Ba) was becoming red (dark grey in the figure) from left to right and exhaling through their mouth when the horizontal bar was becoming green (light grey in the figure) from right to left; (2) control their inhalation amplitude by inhaling through their nose and matching the target on the top vertical bar (Fig. 1Bb) that was becoming red from bottom to top (towards the targeted line); (3) control their exhalation amplitude by exhaling through their mouth and matching the target on the bottom vertical bar (Fig. 1Bc) that was becoming green from bottom to top (towards the targeted line). On average, subjects were able to do both the respiratory conditions within five trials, which demonstrated that training feedback of their respiration was a practical way to induce the respiratory experimental conditions quickly. Following the contractions with the respiratory conditions another set of MVC trials was recorded to determine whether fatigue occurred to the FDI muscle.

Data analysis

Data were acquired with the Spike2 software (Version 6.02; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) and analyzed off-line using custom-written programs in Matlab® (Math Works™ Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA). The respiration, force, and surface EMG signals were analyzed in segments of 4 s (Fig. 2). For the vision condition, segments were taken for 4 s prior to the removal of visual feedback condition, whereas for the no-vision condition segments were taken for 4 s after the removal of visual feedback condition (Fig. 2). Prior to data analysis, the respiration signal was filtered with a 4th-order (bi-directional) Butterworth filter using a 0.02 – 1 Hz band-pass. The force output was filtered with a 4th-order (bi-directional) Butterworth filter using a 0.1 – 15 Hz band-pass. The standard deviation of force was quantified from the detrended force output of the 4 s because any drift from the targeted force (especially during the absence of visual feedback condition) could influence the force variability. This was achieved by removing the linear trend from the force data. The dependent variables were the amplitude of respiration [root mean square (RMS) of the respiration signal], mean force, standard deviation (SD) of force, coefficient of variation of force (CV; (SD of force / mean force) × 100), and the amplitude of the EMG signal (RMS of interference signal).

Fig. 2.

Representative example of respiration, force and EMG of the FDI muscle. The top row represents the respiratory airflow trace, the middle row represents the force trace and the bottom row is the corresponding FDI EMG activity. The analysis was performed from 4 seconds prior to the removal of the visual feedback (visual feedback condition) and immediately 4 seconds after the removal of visual feedback (no visual feedback condition). The left column represents the data recorded from a subject during the normal-amplitude respiratory condition, whereas the right column represents the data recorded from the same subject during the high-amplitude respiratory condition.

In addition, continuous wavelet transforms (Equation 2) were performed on the force and EMG signals. Wavelet transforms were calculated using a base Matlab function developed by Torrence and Compo (1998) (available at URL: http://paos.colorado.edu/research/wavelets). The wavelet transform of a signal determines both the amplitude versus frequency characteristics of the signal and how this amplitude varies with time. The wavelet transform provides other advantages over the Fourier transform that have been discussed elsewhere (Zazula, Karlsson, & Doncarli, 2004). The wavelet represents a set of functions with the form of small waves created by dilations and translations from a simple generator function, Ψ(t), which is called mother wavelet (Addison, 2002). To perform a wavelet transform the Morlet mother wavelet was used (Equation 1, (Torrence & Compo, 1998)).

| (1) |

where η is dimensionless time and w0 is dimensionless frequency (in this study we used w0 = 6, as suggested by (Grinsted, Moore, & Jevrejeva, 2004).

Morlet wavelet (with w0 = 6) is a reasonable choice when performing wavelet analysis since it provides balance between time and frequency localization (Grinsted et al., 2004). The wavelet transform applies the wavelet function as a band-pass filter to the time series (Equation 2). To modify its frequency content, the wavelet function is stretched in time by varying its scale(s) (dilation). For the Morlet wavelet used in this study the wavelet scale is almost equal to the Fourier period (Fourier period = 1.03 s).

| (2) |

where s represents the dilation parameter (scale shifting), τ represents the location parameter (time shifting) and the basic function Ψs,τ (t), is obtained by dilating and translating the mother wavelet Ψ0(t) (Addison, 2002).

From the wavelet transform of the force signal (WX (s, τ)), we defined the absolute scale-averaged wavelet power spectrum (AWPS) as the scale-averaged squared modulus of the wavelet transform (Equation 3).

| (3) |

Additionally, we defined the normalized scale-averaged wavelet power spectrum (NWPS) as AWPS normalized by the sum of AWPS over all scales for each instant of time (Equation 4).

| (4) |

For statistical comparisons, the frequency data of the force signal were divided into 0–1, 1–3, 3–7, and 7–10 Hz frequency bands (see Slifkin et al. 2000 for bands of interest in force). The dependent variables for the spectral analysis of the force signal were the wavelet absolute and normalized power in the above bands averaged across 4 seconds.

To determine the common oscillations between pairs of EMG signals, cross-wavelet spectra of the EMG signals were obtained (Equation 5). To obtain the cross-wavelet spectra of the pair of EMG signals, first wavelet transforms of each EMG signal were calculated separately (Equation 2). From the wavelet transform of both EMG signals, the cross-wavelet transform was calculated (Equation 5).

| (5) |

where W(s,τ)XY is the cross-wavelet transform of signals X (t) and Y (t), W (s, τ)X is wavelet transform of signal X(t), and W (s, τ)Y* is the complex conjugate of the wavelet transform of signal Y (t). We defined the absolute scale-averaged cross-wavelet power spectrum (AXWPS) as the scale averaged modulus of the cross-wavelet transform (Equation 6).

| (6) |

Similarly, we defined the normalized scale-averaged cross-wavelet power spectrum (NXWPS) as AXWPS normalized by the sum of AXWPS over all scales for each instant to time (Equation 7).

| (7) |

The normalized scale-averaged cross-wavelet power spectrum shows the relative importance of each frequency of the wavelet power spectrum. It considers the relative importance of the commonalities in the variance of the two signals in different frequencies as a function of time. We use the cross-wavelet spectra (absolute and normalized) of two EMG signals recorded from the same muscle from 12–60 Hz for the following reasons: (1) Power in the EMG signal from 12–60 Hz reflects the modulation of the motor neuron pool with voluntary effort (Brown, 2000; Neto, Baweja, & Christou, 2010) and it is not associated with the shape of the motor unit action potential (Myers, Erim, & Lowery, 2004; Neto et al., 2010; Neto & Christou, 2009); (2) the cross-wavelet spectrum from two EMG signals within the FDI muscle demonstrates common oscillations within the muscle and it cannot be entirely explained by cross-talk of the two recording sites (Neto et al., 2010). Even if it is influenced by cross-talk it still reflects the overall oscillations in the motor neuron pool of the FDI muscle. Thus, the cross-wavelet spectrum can be used to compare changes in the modulation of the motor neuron pool as a function of time. For statistical comparisons, the frequency data of the EMG signal were divided into 12–30 and 30–60 Hz frequency bands as we have done previously (Neto et al., 2010; Neto & Christou, 2009). The dependent variables for the spectral analysis of the EMG signals were the cross-wavelet absolute and normalized power in the above bands averaged across 4 seconds.

In addition, a Fourier analysis was performed on the respiration signal to calculate the mean respiration frequency for all the respiratory conditions. Autospectral analysis of the respiration signal was obtained using Welch’s average periodogram method with a non-overlapping Hanning window (Matlab). The length of the data segment was 4 s and the sampling frequency was 1 kHz. The window size was 4096, which gave a resolution of 0.244 Hz. The dependent variable for the spectral analysis of the respiration signal was the mean respiration frequency.

Statistical analysis

A three-way ANOVA (2 Visual Feedback Conditions × 2 Force Levels × 3 Respiratory Conditions) with repeated measures on all factors compared respiratory amplitude, mean respiration frequency, mean force, SD of force, CV of force, and EMG amplitude for the different force levels, respiratory conditions, and visual feedback conditions. A four-way ANOVA (2 visual feedback conditions × 3 respiratory conditions × 2 force levels × 4 frequency bands) with repeated measures on all factors compared the absolute and normalized power in the force spectrum for the different force levels, respiratory conditions and visual feedback conditions. A similar model (2 Feedback Conditions × 2 Force Levels × 3 Respiratory Conditions × 2 Frequency Bands) compared the absolute and normalized power in the EMG cross spectrum for the different force levels, visual feedback conditions and respiratory conditions. In addition, multiple linear regression analysis (stepwise) was used to examine the contribution of the change in power at each frequency band from the force and EMG power spectra to the change in SD of force between visual feedback and respiratory conditions. Any subjects that exhibited values outside ± 3SD were excluded as outliers (all subjects in this manuscript exhibited values within ± 3SD). The change for each variable was quantified as follows: [(values at 125% amplitude − values at 100% amplitude)/values at 100% amplitude] × 100. The relative importance of the predictors was estimated with the part correlations (part r), which provide the correlation between a predictor and the criterion, partialling out the effects of all other predictors in the regression equation from the predictor but not the criterion (Green & Salkind, 2002).

Analyses were performed with the SPSS 16.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significant interactions from the ANOVA models were followed by appropriate post-hoc analyses. For example, differences among respiratory conditions were followed with one-way ANOVAs and paired t-tests. Differences between visual feedback conditions and force levels were examined with paired t-tests. Multiple t-test comparisons were corrected using Bonferroni corrections. The alpha level for all statistical tests was .05. Data are reported as means ± SD within the text and as means ± SEM in the figures. Only the significant main effects and interactions are presented, unless otherwise noted.

3. RESULTS

Respiratory amplitude and mean respiration frequency

As expected, the amplitude of respiration was significantly different across the respiratory conditions (respiratory condition main effect: F(2, 36) = 15.03, p < .001), whereas the respiration frequency did not vary with the respiratory conditions (p > .3). On average, the respiratory amplitude for the high-amplitude condition was 125% of the normal-amplitude respiration and for the low-amplitude condition was 85% of the normal-amplitude respiration. The average respiratory rate was 0.24 ± 0.02 Hz (~15 breaths per minute). Interestingly, there was a significant Respiratory Condition × Visual Feedback interaction for the respiratory amplitude, F(2, 36) = 4.928, p = .013, which indicated that the amplitude of respiration was lower at the low-amplitude respiratory condition when visual feedback was removed.

MVC force and EMG

To determine whether our experimental protocol induced muscle fatigue to our subjects we compared the MVC and EMG amplitude before and immediately after the experimental session. Both the MVC force and EMG amplitude did not change significantly (t > .3, p > .2). Specifically, the MVC force was 33.5 ± 14.2 N prior to the experimental protocol and 34.4 ± 17.1 N after the experimental protocol. The EMG amplitude was 452 ± 228 µV prior to the experimental protocol and 494 ± 222 µV after the experimental protocol. These findings demonstrate that the experimental protocol did not induce any fatigue to our subjects.

Mean force

The mean force increased significantly with force level, F(1, 18) = 86.53, p < .001, and was greater in the presence of visual feedback, F(1, 18) = 27.9, p < .001. There was a significant Visual Feedback Condition × Force interaction, F(1, 18) = 13.8, p = .002, indicating that the mean force was significantly greater in the presence of visual feedback at 50% MVC. There were no significant interactions with respiration, which demonstrates that subjects were able to maintain the targeted force equally well under the different respiratory conditions.

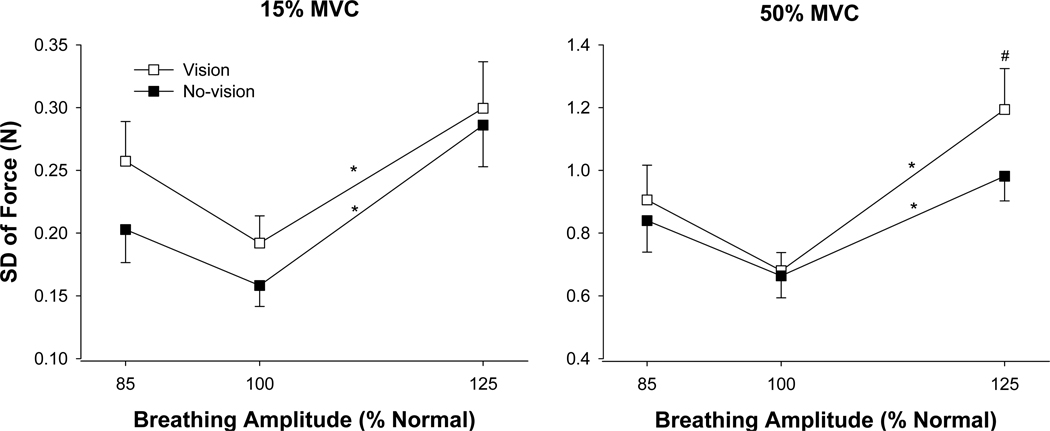

Force variability

Force variability was quantified as the SD of force and CV of force. The SD of force increased significantly with the force level, F(1, 18) = 84.9, p < .001, and the SD of force was higher in the presence of visual feedback (visual feedback condition main effect: F(1, 18) = 7.8, p = .012. There was also a main effect for respiratory conditions, F(2, 36) = 11.27, p = .001. The greatest SD of force occurred during the high-amplitude condition (Fig. 3). There was a significant Respiratory Condition × Force interaction, F(2, 36) = 5.8, p = .006, and a significant Force × Visual Feedback Condition × Respiratory Condition interaction, F(2, 36) = 4.5, p = .023; Fig. 3). The three-way interaction indicated the following: (1) for both visual feedback conditions, the SD of force was significantly greater during the high-amplitude respiratory condition compared with the normal-amplitude respiratory condition, whereas the SD of force was similar for the low-amplitude respiratory condition and the normal condition; (2) at 50% MVC, the presence of visual feedback exacerbated the SD of force for the high-amplitude respiratory condition.

Fig. 3.

SD of force during different respiratory and visual feedback conditions. The SD of force increased significantly (p < .001) with the level of force and on average was also significantly (p = .012) higher with visual feedback (open squares) compared with no-visual feedback (filled squares). The SD of force was significantly (*) higher with high-amplitude respiration during both feedback conditions at 15% MVC (left panel) and 50% MVC (right panel) compared with normal-amplitude respiration. At 50% MVC visual feedback exacerbated the SD of force during the high-amplitude respiratory condition (#).

Because the mean force was significantly different for the two visual feedback conditions at 50% MVC, we also examined the CV of force. The results were similar to the SD of force. The CV of force varied significantly with force level, F(1, 18) = 26.56, p < .001, and was also significantly higher (visual feedback condition main effect: F(1, 18) = 6.2, p = .023; Fig. 4) in the presence of visual feedback (4.66 ± 1.2 vs. 4.2 ± 1.1 %). The Force × Visual Feedback Condition × Respiratory Condition interaction was also significant, F(2, 36) = 4.25, p = .027; Fig. 4) and indicated the following: (1) similar to the SD of force, the CV of force was significantly greater during the high-amplitude respiratory condition compared with the normal-amplitude respiratory condition; (2) on average, the CV of force was greater with visual feedback due to differences (statistically not significant) between the two visual feedback conditions at low- and normal-amplitude respiration for 15% MVC and high-amplitude respiration for 50% MVC; 3) the CV of force was significantly greater during the high-amplitude respiratory condition compared with the low-amplitude respiratory condition only at 15% MVC.

Fig. 4.

CV of force during different respiratory and visual feedback conditions. The CV of force increased significantly (p < .001) with the level of force and was also significantly (p = .023) higher with visual feedback (open diamonds) compared with no-visual feedback (filled diamonds). The CV of force was significantly (*) greater with high-amplitude respiration compared with normal-amplitude respiration at both force levels. In addition, the CV of force was significantly (#) greater with high-amplitude respiration compared with low-amplitude respiration only at 15% MVC. Finally, on average, the CV of force was greater with visual feedback primarily due to differences at low- and normal-amplitude respiration at 15% MVC and high-amplitude respiration at 50% MVC.

Force Power Spectrum

Absolute power

There was a significant Frequency Band × Visual Feedback × Respiratory Condition interaction, F(6, 102) = 4.94, p = .031 (Fig. 5A, B), and based on post hoc tests indicated the following: The power spectra varied with the respiratory conditions during the visual feedback condition (Fig. 5A), whereas the power spectra of the three respiratory conditions were similar during the no-visual feedback condition (Fig. 5B). Specifically, during the visual feedback condition subjects exhibited greater power from 0–1 Hz and 1–3 Hz during the high-amplitude respiration compared with the normal- and low-amplitude respiratory conditions. Furthermore, the power from 0–1 Hz and 1–3 Hz was greater during the visual feedback condition than during the no-visual feedback condition.

Fig. 5.

Power spectrum of the force output. This figure demonstrates the change in power for the absolute (top row) and normalized (bottom row) power spectra of force in the presence (left column; open symbols) and absence of visual feedback (right column; filled symbols) during the various respiratory conditions (low-, normal-, and high-amplitude respiration). (A) In the presence of visual feedback subjects exhibited significantly greater absolute power of force during high-amplitude respiration from 0–1 and 1–3 Hz (*). (B) There were no differences in the absolute power spectra of force in the absence of visual feedback during all respiratory conditions. (C) In the presence of visual feedback subjects exhibited significantly greater (p = .002) normalized power from 0–1 Hz (*) and significantly (p < .001) lower normalized power from 3–7 Hz (#) during both the experimental respiratory conditions compared with normal-amplitude respiration. (D) In the absence of visual feedback subjects exhibited significantly greater (p = .002) normalized power from 0–1 Hz (*) and significantly (p < .001) lower normalized power from 3–7 Hz (#) during both experimental respiratory conditions compared with normal-amplitude respiration.

Normalized power

There was a significant Frequency Band × Respiratory condition interaction, F(6, 108) = 7.52, p = .001 (Fig. 5C, D) and based on post hoc tests indicated the following: Subjects exhibited greater normalized power from 0–1 Hz (66.9 ± 8.7 vs. 59.8 ± 7.3%; t = 3.2, p = .002) and lower normalized power from 3–7 Hz (5.8 ± 3.2 vs. 10.4 ± 3.9 %; t = −4.89, p < .001) during the high-amplitude respiratory condition compared with the normal-amplitude respiratory condition. Furthermore, subjects exhibited lower normalized power from 3–7 Hz during the low-amplitude respiratory condition than the normal-respiratory condition (7.05 ± 4 vs. 10.4 ± 3.9 %; t = −3.2, p = .002).

EMG amplitude

The FDI EMG amplitude increased significantly with the force level, F(1, 18) = 72.23, p < .001. The FDI EMG amplitude was significantly greater in the presence of visual feedback (visual feedback condition main effect; F(1, 18) = 24.5, p < .001). There was also a significant Visual Feedback Condition × Force interaction, F(1, 18) = 13.74, P < .002, indicating that the FDI EMG activity was higher in the presence of visual feedback especially at 50% (266 ± 108 vs. 235 ± 98 V). There was no significant interaction with the respiratory conditions, which demonstrates that subjects exhibited similar EMG amplitude during the different respiratory conditions.

EMG cross-wavelet spectrum

Absolute power from 12–60 Hz

The absolute power from 12–30 and 30–60 Hz increased with the level of force (force level main effect: F(1, 18) = 27.8, p < .001). In addition, there was a significant Frequency Band × Force Level interaction, F(1, 18) = 9.45, p = .007, indicating that the absolute power from 30–60 Hz increased significantly with the level of force.

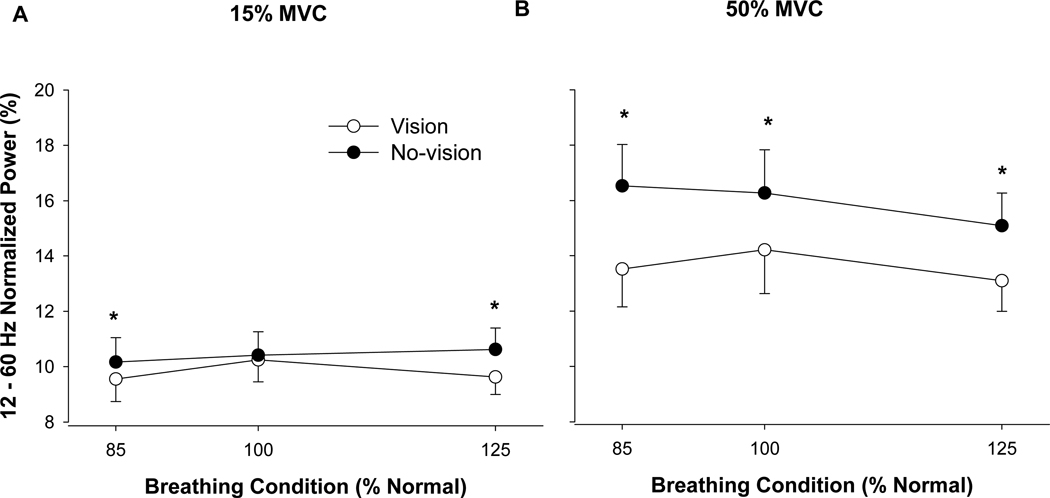

Normalized power from 12–60 Hz

There was a significant Visual Feedback × Force level × Respiratory Condition interaction, F(2, 36) = 4.52, p = .017 (Fig. 6), and based on the post-hoc tests indicated the following: At 15% MVC the normalized power was significantly (p < .001) lower in the presence of visual feedback only during the experimental respiratory conditions (low- and high-amplitude) but not during normal-amplitude respiration. In contrast, at 50% MVC the normalized power from 12–60 Hz was significantly (p < .001) lower in the presence of visual feedback during all respiratory conditions.

Fig. 6.

Cross-wavelet spectrum of the EMG output. This figure demonstrates a change in the normalized power spectra of the EMG signals from 12–60 Hz at 15% MVC (left panel) and 50% MVC (right panel) in the presence (open circles) and absence (filled circles) of visual feedback during the three respiratory conditions. (A) at 15% MVC the normalized power of the EMG signals was significantly lower in the presence of visual feedback (*) only during the experimental respiratory conditions. (B) At 50% MVC the normalized power was significantly lower in the presence of visual feedback (*) during all the respiratory conditions.

Associations between changes in force variability and changes in force and EMG power spectra

The main force variability findings of the study were: (1) for both force levels, subjects exhibited greater force variability during the high-amplitude respiratory condition compared with the normal-amplitude respiratory condition; (2) at 50% MVC, visual feedback exacerbated the force variability during the high-amplitude respiratory condition. We performed multiple regression analysis to determine the associated changes in the power spectrum of force and cross-wavelet spectrum of EMG from 12–60 Hz (absolute and normalized). The results are summarized in Fig. 7 and the statistics are provided below.

Fig. 7.

Associations between changes in SD of force and changes in force and EMG power spectra. For all conditions that significantly changed the SD of force, the increase in the SD of force was associated with an increase in force oscillations from 0–3 Hz. Nonetheless, the only condition that demonstrated a significant involvement of the primary agonist muscle (FDI) was the greater change in SD of force with high-amplitude respiration and visual feedback at 50% MVC. We found that the amplified force oscillations from 0–1 Hz with visual feedback at moderate force levels were associated with greater modulation at 12–30 Hz in the EMG signal of the primary agonist muscle (R2 = .24, p = .035).

Changes from normal-amplitude respiration with visual feedback

At 15% MVC with visual feedback, the 71.6% increase in force variability during the high-amplitude condition was associated with greater power from 1–3 Hz (R2 = .757, part r = .87, p < .001). The increase in the 1–3 Hz power in the force power spectrum and the increase in force variability were not associated with changes in the absolute or normalized power from 12–60 Hz of the EMG signal (P > .2). In contrast, at 50% MVC with visual feedback, the 104.5% increase in force variability during the high-amplitude condition was associated with greater power from 0–1 Hz (R2 = .685, part r = .83, p < .001). The increase in the 0–1 Hz power in the force power spectrum and the increase in force variability were not associated with changes in the absolute or normalized power from 12–60 Hz of the EMG signal (p > .7).

Changes from normal-amplitude respiration without visual feedback

At 15% MVC without visual feedback, the 92.4% increase in force variability during the high-amplitude condition was associated with greater power from 0–1 Hz (R2 = .785, part r = .88, p < .001). The increase in the 0–1 Hz power in the force power spectrum and the increase in force variability were not associated with changes in the absolute or normalized power from 12–60 Hz of the EMG signal (P > .07). In contrast, at 50% MVC without visual feedback, the 71.4% increase in force variability during the high–amplitude respiratory condition was associated with greater power from 0–1 Hz and 1–3 Hz (R2 = .842, part r0–1Hz = .45, part r1–3Hz = .44, p < .001). The increase in the 0–1 Hz and 1–3 power in the force power spectrum and the increase in force variability were not associated with changes in the absolute and normalized power from 12–60 Hz of the EMG signal (p > .16).

Changes with vision

At 50% MVC, the increase in force variability with high-amplitude respiration compared with normal-respiration was significantly greater (29.3%) for the visual feedback condition. This greater increase in force variability with visual feedback was associated with greater power from 0–1 Hz in the force power spectrum (R2 = .816, part r = .903, p < .001). The increase in the 0–1 Hz power in the force power spectrum was associated with greater absolute power from 12–30 Hz in the EMG signal (R2 = .237, part r = .487, p = .035).

4. Discussion

Recent evidence suggests that forced inspiration and expiration impairs the control of force during constant isometric contractions by increasing force variability. However, it remains unclear whether these respiratory-induced increases in force variability are caused by changes in the neural activation of the involved muscles, the attempt to control two tasks at the same time (dual tasking), or an interaction of respiration with visual feedback of force. In this study, therefore, we aimed to clarify these issues. Our findings suggest the following: (1) High-amplitude respiration (125% of normal) increased force variability by increasing power in force oscillations from 0–3 Hz. This effect, however, was not associated with dual tasking or changes to the neural activation of the agonist muscle. (2) Removal of visual feedback reduced variability in force during high-amplitude respiration at moderate levels of voluntary effort. This reduction in force variability was associated with lower power in force oscillations from 0–1 Hz and lower power from 12–30 Hz in agonist muscle activity. Overall, these findings suggest that a significant portion of the amplified force variability with high-amplitude respiration cannot be explained from changes in the neural activation of muscle, dual tasking, or visuomotor corrections. At moderate levels of voluntary effort, however, visual feedback of force exacerbates the respiratory-induced changes in force variability most likely due to amplified visuomotor corrections.

Respiratory amplitude and force control

We found that high-amplitude respiration (125% of normal amplitude at a normal rate) increased force variability during constant isometric contractions at low and moderate levels of voluntary effort. Therefore, our results support previous findings by Turner and Jackson (2002) and Li and Yasuda (2007). We extend these findings by providing evidence that the amplification in force variability with high-amplitude respiration cannot be explained by dual tasking or changes to the neural activation of the single agonist muscle involved in this task.

When subjects attempt to control both force and respiration simultaneously this can be viewed as a dual task because two tasks are competing for processing resources from the brain at the same time. Thus, the cognitive effort (load) could be greater when both force and respiration are controlled voluntarily (e.g., high-amplitude respiration) compared with the normal respiratory condition where only the force output is controlled voluntarily. Because greater cognitive loads have been associated with amplified force variability (Yoon et al., 2009), dual tasking is a potential explanation to the amplified force variability with high-amplitude respiration. Our results suggest that dual tasking cannot entirely explain the increased force variability with high-amplitude respiration. This is demonstrated by the similar force variability during the normal- and low-amplitude respiratory conditions (subjects needed to control both respiration at 75% of normal-amplitude and force simultaneously).

Furthermore, the amplified force variability with high-amplitude respiration cannot be explained by changes in the neural activation of muscle (see Fig. 7). Our task was abduction of the index finger, which is primarily controlled by a single agonist muscle (first dorsal interosseus (Chao et al., 1989; Li et al., 2003)) and thus it is suitable to determine whether respiratory-induced changes in force variability were associated with changes in the neural activation of the involved muscle. We provide the following two pieces of evidence that demonstrate no changes in muscle activity with high-amplitude respiration: First, we found that the overall EMG amplitude did not change with variations in respiration and thus EMG amplitude cannot explain the changes in force variability with high-amplitude respiration. Second, all the significant respiratory-induced changes in force variability were not associated with changes in the oscillations in muscle activity from 12–60 Hz (see Fig. 7). We focused from 12–60 Hz in muscle activity for the following reasons: (1) The power from 12–60 Hz in the EMG signal is not influenced by the shape of the action potential and thus provide an index of the modulation of the motor neuron pool (Myers et al., 2004; Neto et al., 2010; Neto & Christou, 2009). (2) The 12–30 Hz band, commonly known as the beta band, has been associated with cortical input to the motor neuron pool (Brown, 2000; Conway et al., 1995; Baker, Olivier, & Lemon, 1997) and may reflect motor unit synchronization (Christou, Rudroff, Enoka, Meyer, & Enoka, 2007; Moritz, Christou, Meyer, & Enoka, 2005); 3) The 30–60 Hz band in the EMG (Piper band) has been associated with stronger voluntary effort and similar activation at the cortical level (Brown, 2000; Brown, Salenius, Rothwell, & Hari, 1998). Recently, we demonstrated that power in both the 12–30 Hz and 30–60 Hz bands increases with voluntary effort (Neto et al., 2010). Our current results also support this finding (see Fig. 5). The EMG findings from this study, nonetheless, are limited to the overall muscle activity. More subtle changes may occur at the motor unit level, which we have not identified. For example, previous studies have shown that normal respiration may influence the activation of trapezius motor units at frequencies ranging from 0–1 Hz (Westgaard, Bonato, & Westad, 2006), which could contribute to the variability in force (De Luca, Foley, & Zeynep, 1996). Future studies should address the influence of high-amplitude respiration on the modulation of motor unit discharge.

The respiratory-induced changes in force variability, however, were associated with changes in the structure of force output. Specifically, these changes occurred below 3 Hz in the force output (see Fig. 7). These low-frequency oscillations (especially from 0–1 Hz) have been associated with visuomotor corrections ( Baweja et al., 2009, 2010; Prodoehl & Vaillancourt, 2010; Slifkin et al., 2000). Nonetheless, we cannot entirely attribute these changes due to visuomotor corrections because similar changes in force oscillations occurred in the presence and absence of visual feedback. Given that we cannot provide evidence that the respiratory-induced changes in force variability were due to dual tasking or neural activation of the agonist muscle, we conclude that these changes can be partially explained by a mechanical effect. For example, when subjects performed forced ventilation (compared with the Valsalva maneuver) during constant isometric tasks the movement of the thorax altered the positional stability of the shoulder girdle (via the scapulohumeral articulations) and subsequently the stability of the wrist, metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints (Li & Laskin, 2006; Li & Yasuda, 2007). It is possible, therefore, that this mechanical linkage may contribute to the variability of perpendicular force at the index finger by mechanically altering the position of the index finger. This possibility may explain why force variability was greater during the high-amplitude respiration but not during the low-amplitude respiration when compared with normal-amplitude respiration.

Interaction of respiratory amplitude and visual feedback of force

In this study we provide novel evidence that high-amplitude respiration may interact with visual feedback of the force output to exacerbate force variability, at least during moderate levels of voluntary effort. During high-amplitude respiration at 50% MVC subjects exhibited ~30% greater change in force variability from normal respiration when they received visual feedback of their force. The greater change in force variability was strongly associated (R2 = .82) with greater oscillations in force from 0–1 Hz, which have been previously associated with visuomotor corrections (Baweja et al., 2010; Prodoehl & Vaillancourt, 2010; Slifkin et al., 2000). Interestingly, the amplified oscillations in force from 0–1 Hz were associated with changes (greater power) in the oscillatory activation of the primary agonist muscle from 12–30 Hz. It is possible, therefore, that respiratory-induced changes to the force output stimulated greater corrections with visual feedback of the force (visuomotor corrections) and consequently exacerbated force variability. In addition, it seems that visuomotor corrections were potentially mediated by an increase in the oscillatory input to the agonist muscle from 12–30 Hz, which could reflect greater voluntary effort (Neto et al., 2010) or amplified motor unit synchronization (Christou et al., 2007; Moritz et al., 2005).

Visual feedback and changes to muscle activity

In addition to providing evidence that visual feedback can interact with the respiratory-induced changes in the force output to alter force variability, our results provide evidence that the modulation of the agonist muscle activity differs in the presence and absence of visual feedback (see Fig. 6). For example, even during the normal respiratory condition at moderate levels of effort, subjects exhibited greater normalized power from 12–60 Hz in the absence of visual feedback compared with when they received visual feedback of their force output. This result suggests that subjects activate their agonist muscle differently with visual feedback. It can potentially explain some of the previous observations that force variability decreases with removal of visual feedback at moderate levels of effort (Baweja et al., 2009). In addition, it may provide an explanation to the age-associated decreases in force variability with removal of visual feedback (Christou, Baweja, Kennedy, & Wright, 2009; Tracy 2007; Tracy et al., 2007;. More research is needed, however, to determine whether amplified oscillations from 12–60 Hz can reduce force variability.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that high-amplitude respiration increases force variability during constant isometric contractions. A significant portion of the amplified force variability with high-amplitude respiration cannot be explained from altered activation of the agonist muscle, dual tasking, or visuomotor corrections. Nonetheless, at moderate levels of voluntary effort, visual feedback of force exacerbates the respiratory-induced changes in force variability most likely due to amplified visuomotor corrections mediated by changes in the neural activation of the agonist muscle.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Meredith A. Smith and Julie D. Martinkewiz for data collection and the help of Jonathan D. Leake for computer programming. This study was supported by R01 AG031769 to Evangelos A. Christou.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Addison PS. The illustrated wavelet transform handbook. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, New York; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baker SN, Olivier E, Lemon RN. Coherent oscillations in monkey motor cortex and hand muscle EMG show task-dependent modulation. Journal of Physiology. 1997;501(Pt 1):225–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.225bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baweja HS, Kennedy DM, Vu JL, Vaillancourt DE, Christou EA. Greater amount of visual feedback decreases force variability by reducing force oscillations from 0–1 and 3–7 Hz. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2010;108:935–943. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1301-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baweja HS, Patel BK, Martinkewiz JD, Vu JL, Christou EA. Removal of visual feedback alters muscle activity and reduces force variability during constant isometric contractions. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;197:35–47. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1883-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. Cortical drives to human muscle: The Piper and related rhythms. Progress in Neurobiology. 2000;60:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Salenius S, Rothwell JC, Hari R. Cortical correlate of the Piper rhythm in humans. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:2911–2917. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao EYS, An KN, Cooney WP, Linschied RL. Biomechanics of the hand. A basic research study. Teaneack, NJ: World Scientific Publishing; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Christou EA. Visual feedback attenuates force fluctuations induced by a stressor. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37:2126–2133. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000178103.72988.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou EA, Baweja HS, Kennedy DM, Wright DL. Society for Neuroscience. Chicago, IL: 2009. Age-associated differences in learning novel fine motor tasks. [Google Scholar]

- Christou EA, Grossman M, Carlton LG. Modeling variability of force during isometric contractions of the quadriceps femoris. Journal of Motor Behavior. 2002;34:67–81. doi: 10.1080/00222890209601932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou EA, Jakobi JM, Critchlow A, Fleshner M, Enoka RM. The 1- to 2- Hz oscillations in muscle force are exacerbated by stress, especially in older adults. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2004;97:225–235. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00066.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou EA, Rudroff T, Enoka JA, Meyer F, Enoka RM. Discharge rate during low-force isometric contractions influences motor unit coherence below 15 Hz but not motor unit synchronization. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;178:285–295. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou EA, Tracy BL. Aging and motor output variability. In: Davids K, Bennett S, Newell K, editors. Movement system variability. Champaign-Urbana, IL: Human Kinetics; 2005. pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Conway BA, Halliday DM, Farmer SF, Shahani U, Maas P, Weir AI, Rosenberg JR. Synchronization between motor cortex and spinal motoneuronal pool during the performance of a maintained motor task in man. Journal of Physiology. 1995;489(Pt 3):917–924. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CJ, Foley P, Zeynep E. Motor unit control properties in constant-force isometric contractions. Journal of Physiology. 1996;76:1503–1516. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D, Rassler B, Hefter H. Coordination between breathing and forearm movements during sinusoidal tracking. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;81:288–296. doi: 10.1007/s004210050045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoka RM, Christou EA, Hunter SK, Kornatz KW, Semmler JG, Taylor AM, Tracy BL. Mechanisms that contribute to differences in motor performance between young and old adults. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2003;13:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(02)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SB, Salkind NJ. Using SPSS for the Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and anderstanding data. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grinsted A, Moore JC, Jevrejeva S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics. 2004;11:561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Homma T, Sakai T. Ramification pattern of intermetacarpal branches of the deep branch (ramus profundus). of the ulnar nerve in the human hand. Acta Anatomica (Basel) 1991;141:139–144. doi: 10.1159/000147113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SK, Critchlow A, Shin IS, Enoka RM. Fatigability of the elbow flexor muscles for a sustained submaximal contraction is similar in men and women matched for strength. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2004;96:195–202. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00893.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberg EM, Mateika JH, Cherry L, Gordon AM. Internal representations underlying respiration during object manipulation. Brain Research. 2003;982:270–279. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Laskin JJ. Influences of ventilation on maximal isometric force of the finger flexors. Muscle and Nerve. 2006;34:651–655. doi: 10.1002/mus.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Yasuda N. Forced ventilation increases variability of isometric finger forces. Neuroscience Letters. 2007;412:243–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZM, Pfaeffle HJ, Sotereanos DG, Goitz RJ, Woo SL. Multi-directional strength and force envelope of the index finger. Clinical Biomechanics (Bristol, Avon) 2003;18:908–915. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz CT, Christou EA, Meyer FG, Enoka RM. Coherence at 16–32 Hz can be caused by short-term synchrony of motor units. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;94:105–118. doi: 10.1152/jn.01179.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers LJ, Erim Z, Lowery MM. Time and frequency domain methods for quantifying common modulation of motor unit firing patterns. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation. 2004;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto OP, Baweja HS, Christou EA. Increased voluntary drive is associated with changes in the common oscillations from 13–60 Hz of interference but not rectified electromyography. Muscle and Nerve. 2010;42:348–354. doi: 10.1002/mus.21687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto OP, Christou EA. Rectification of the EMG signal impairs the identification of oscillatory input to the muscle. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2009;103:1093–1103. doi: 10.1152/jn.00792.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto OP, Marzullo AC, Baweja HS, Christou EA. Society for Neuroscience. Chicago, IL: 2009. Removal of visual feedback but not changes in breathing influence muscle activity during constant isometric contractions. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodoehl J, Vaillancourt DE. Effects of visual gain on force control at the elbow and ankle. Experimental Brain Research. 2010;200:67–79. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1966-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassler B, Bradl U, Scholle H. Interactions of breathing with the postural regulation of the fingers. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2000;111:2180–2187. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassler B, Kohl J. Coordination-related changes in the rhythms of breathing and walking in humans. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;82:280–288. doi: 10.1007/s004210000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassler B, Nietzold I, Waurick S. Phase-dependence of breathing and finger tracking movements during normocapnia and hypercapnia. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 1999;80:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s004210050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifkin AB, Vaillancourt DE, Newell KM. Intermittency in the control of continuous force production. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;84:1708–1718. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.4.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnoff JJ, Newell KM. Aging, visual intermittency, and variability in isometric force output. Journals of Gerontology. Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61:P117–P124. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.p117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrence C, Compo GP. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 1998;79:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy BL. Force control is impaired in the ankle plantarflexors of elderly adults. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2007;101:629–636. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy BL, Dinenno DV, Jorgensen B, Welsh SJ. Aging, visuomotor correction, and force fluctuations in large muscles. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2007;39:469–479. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802d3ad3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D, Jackson S. Resistive loaded breathing has a functional impact on maximal voluntary contractions in humans. Neuroscience Letters. 2002;326:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt DE, Slifkin AB, Newell KM. Intermittency in the visual control of force in Parkinson's disease. Experimental Brain Research. 2001a;138:118–127. doi: 10.1007/s002210100699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt DE, Slifkin AB, Newell KM. Visual control of isometric force in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychologia. 2001b;39:1410–1418. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westgaard RH, Bonato P, Westad C. Respiratory and stress-induced activation of low-threshold motor units in the human trapezius muscle. Experimental Brain Research. 2006;175:689–701. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0587-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon T, Keller ML, De-Lap BS, Harkins A, Lepers R, Hunter SK. Sex differences in response to cognitive stress during a fatiguing contraction. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2009;107:1486–1496. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00238.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazula D, Karlsson S, Doncarli C. In: Elelctromyography: Physiology, engineering, and noninvasive applications. Merletti R, editor. New Jersey: Johnson Weily & Sons, Hoboken; 2004. pp. 259–304. [Google Scholar]