Abstract

Background

Carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT) is a marker of cardiovascular disease associated with incident stroke. We study whether IMT rate-of-change is associated with stroke.

Materials and Methods

We studied 5028 participants of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) composed of whites, Chinese, Hispanic and African-Americans free of cardiovascular disease. In this MESA IMT progression study, IMT rate-of-change (mm/year) was the difference in right common carotid artery (CCA) far-wall IMT (mm) divided by the interval between two ultrasound examinations (median interval of 32 months). CCA IMT was measured in a region free of plaque. Cardiovascular risk factors and baseline IMT were determined when IMT rate-of-change was measured. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models generated Hazard risk Ratios (HR) with cardiovascular risk factors, ethnicity and education level/income as predictors.

Results

There were 42 first time strokes seen during a mean follow-up of 3.22 years (median 3.0 years). Average age was 64.2 years, with 48% males. In multivariable models, age (HR: 1.05 per year), systolic blood pressure (HR 1.02 per mmHg), lower HDL cholesterol levels (HR: 0.96 per mg/dL) and IMT rate-of-change (HR 1.23 per 0.05 mm/year; 95% C.L. 1.02, 1.48) were significantly associated with incident stroke. The upper quartile of IMT rate-of-change had an HR of 2.18 (95% C.L.: 1.07, 4.46) compared to the lower three quartiles combined.

Conclusion

Common carotid artery IMT progression is associated with incident stroke in this cohort free of prevalent cardiovascular disease and atrial fibrillation at baseline.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Risk Factors, Carotid Arteries, Carotid Intima Media Thickness, stroke

Introduction

Carotid artery intima-thickness (IMT) is a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis associated with cardiovascular risk factors and predictive of incident stroke1-4.

The possible association between change in IMT over time and incident stroke is not well studied. In a literature review, we found one study that addressed this issue. The European Lacipidine Study on Atherosclerosis (ELSA) study, a double-blind randomized anti-hypertensive therapy study, investigated the associations of IMT progression with cardiovascular outcomes5. ELSA reported a positive association between stroke and baseline IMT but not with change in IMT5.

We hypothesize that IMT rate-of-change is associated with incident stroke. We study the possible associations between incident stroke and IMT rate-of-change taking into consideration cardiovascular risk factors in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, a multi-ethnic cohort constituted of individuals aged 45 to 84 years, free of prevalent cardiovascular disease at enrollment and composed of four ethnicities: whites, African-Americans, Chinese, and Hispanics.

Materials and Methods

Population

MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) is composed of a multiethnic population of 6814 men and women aged from 45 to 84 years including whites, African-American, Hispanics, and Chinese participants6 enrolled between July 2000 and August 2002. Participants were not enrolled if they had physician diagnosis of heart attack, stroke, transient ischemic attack, heart failure, angina, atrial fibrillation or history of any cardiovascular procedure. Participants with weight above 300 lbs, pregnancy, or any medical conditions that would prevent long-term participation were excluded. MESA protocols and all studies described herein have been approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all collaborating institutions. The participants studied underwent carotid artery imaging at first visit (visit 1). One half of the participants were imaged at one of two follow-up visits: the first half from September 2002 through January 2004 and the second half from March 2004 through July 2005. The mean interval between visits was 2.5 years.

Risk factors and anthropomorphic variables

The cardiovascular disease risk factors used are components of the updated Framingham Risk Score and include age, sex, smoking and diabetes status, systolic blood pressure, LDL and HDL cholesterol and treatment of hypertension7to which were added ethnicity income and education levels.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, and medical history were self-reported. Current smoking was defined as self-report of a cigarette in the last 30 days. Resting blood pressure was measured three times in the seated position using a Dinamap model Pro 100 automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer (Critikon, Tampa, Florida). The average of the last two measurements was used.

Lipid levels were measured after a twelve-hour fast. The presence of diabetes mellitus was based on self-reported physician diagnosis, use of insulin and/or oral hypoglycemic agent, or a fasting glucose value ≥126 mg/dL8.

Education was self-reported at visit 1 as 4 levels with level 1 as less than high school; level 2: high school or General Educational Development (GED) or associate degree or some college or technical school equivalent; level 3: college graduate and level 4: graduate school or advanced degree. Total family income for the year preceding the second ultrasound examination was specified as 4 categories: < $25,000, $25,000 to $50,000, $50,000 to $100,000, above $100,000.

Risk factors were obtained at visit #2 and visit #3 respectively in the cohort members having their second carotid examination.

Carotid artery measures

Participants were examined supine with the head rotated 45° towards the left side. Imaging was done in the plane parallel to the neck with the jugular vein lying immediately above the common carotid artery (or at 45 degrees from the vertical if the internal jugular vein is not visualized). Images of the right common carotid artery were centered 10 to 15 mm below (caudad to) the right common carotid artery bulb. A matrix array probe (M12L, General Electric, Milwalkee, WI) was used, with the frequency set at 13 MHz and at 32 frames-per-second. A super-VHS videotape recording was then made for 20 seconds. Images were digitized at 30 frames-per-second and automated diameter measurements were made from this video segment using customized software. End-diastolic images (smallest diameter of the artery) were captured.

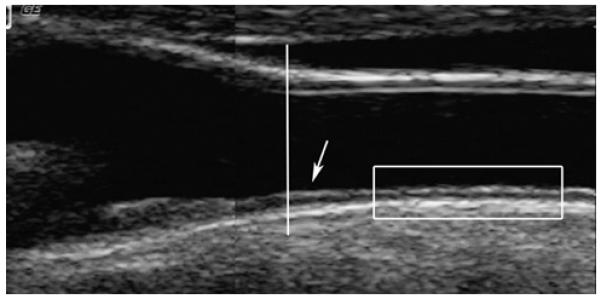

IMT measurements were made on the far-wall of the common carotid artery over a distance of approximately 10 mm starting at least 5 mm to 10 mm below (caudad to) the right common carotid artery bulb (Figure 1). Carotid artery plaque was excluded. Trained readers traced the key two interfaces of the far wall in order to obtain manual tracings. These tracings were then used to calculate mean IMT.

Figure 1.

The location of the common carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) measurements (rectangular box) is approximately 0.5 to 1.0 cm below the bulb (vertical line). The arrow points to a site of focal thickening just before the carotid bulb (dilation of the carotid lumen; vertical line). This site was excluded in order not to include early plaque formation.

Reproducibility was assessed by blinded replicate readings of IMT performed by two readers. One reader re-read 66 studies for a between-reader correlation coefficient of 0.84 (n = 66) and the other re-read 48 studies for a correlation coefficient of 0.86.

IMT rate-of-change in mm/year was measured as the difference in IMT divided by the interval between ultrasound examinations and treated as a risk factor.

Outcomes

Incident strokes were determined during three follow-up examinations and by telephone interview conducted every 9 to 12 months to inquire about all interim hospital admissions, cardiovascular outpatient diagnoses, and deaths. Copies were obtained of all death certificates and of all medical records for hospitalizations and outpatient cardiovascular diagnoses. Two physicians from the MESA study events committee independently reviewed all medical records for end-point classification and assignment of incidence dates. Stroke was defined as a focal neurological deficit lasting 24 hours or more, or as a clinically relevant lesion on brain imaging for symptoms less than 24 hour duration. Patients with focal neurological deficits secondary to brain trauma, tumor, infection, or other nonvascular cause were excluded.

We excluded 46 individuals during the interval between the two ultrasounds: 23 with incident stroke and 23 with examinations after their last clinic evaluation. Of 5490 individuals with IMT progression data and outcomes, we studied 5028 individuals with complete risk factor data.

Statistical analyses

The mean (and standard deviation) values of continuous variables and the distribution of dichotomous variables as % in each group are shown. Non-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the associations between individual risk factors and time to stroke.

Multivariable Cox-regression models were fit with time to stroke as the outcome variable and the component risk factors of the upgraded Framingham Risk Score as predictors. Individuals left the survival analysis at the time of their first stroke or at the time of their last follow-up and not for intervening events such as myocardial infarction. Additionally the models were adjusted for ethnicity, IMT, education and income. Basic assumptions of the models were tested. These analyses were run using SAS version 9.1 (Cary, NC) and two-sided p-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean age of our population is 64.2 years, with 52% women and 39.5% whites, 25.7% African-Americans, 22% Hispanics and 12.8% Chinese. There were 42 incident strokes during a mean follow-up interval of 3.2 years in 5028 individuals.

Risk factors are shown in Table 1. The mean IMT rate-of-change was 0.01 +/− 0.05 mm/year. Quartiles of IMT rate-of-change were −0.367 to 0.00004 mm/year, 0.00004 to 0.0115 mm/year, 0.0116 to 0.0264 mm/year and 0.0264 to 0.472 mm/year with corresponding stroke rates of 7/4536, 7/3464, 9/3641 and 19/4587 per year of follow-up. Chinese had the lowest stroke incidence rate. In unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models, age, HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication use, income, carotid IMT and IMT rate-of-change as quartiles showed significant associations with incident stroke. IMT rate-of-change, as a continuous variable, had borderline significance (p = 0.051).

Table 1.

Distribution of risk factors and incident stroke.

| Variable | Total | No Stroke | Stroke | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 64.2±10.1 | 64.2±10.1 | 70.6±11.3 | 0.0007 |

| Sex (Male) | 2411 (48.0%) | 2392 (48.0%) | 19 (45.2%) | 0.74 |

| Ethnicity | 0.13 | |||

| Caucasian White | 1984 (39.5%) | 1962 (39.4%) | 22 (52.4%) | . |

| Chinese | 646 (12.8%) | 645 (12.9%) | 1 (2.4%) | . |

| African-American | 1292 (25.7%) | 1281 (25.7%) | 11 (26.2%) | . |

| Hispanic | 1106 (22.0%) | 1098 (22.0%) | 8 (19.0%) | . |

| SBP (mm/Hg) | 123.2±20.7 | 123.1±20.6 | 138.8±22.7 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Medication (yes) | 2171 (43.2%) | 2143 (43.0%) | 28 (66.7%) | 0.002 |

|

LDL Cholesterol

(mg/dL) |

113.1±32.1 | 113.1±32.1 | 112.7±30.6 | 0.93 |

|

HDL Cholesterol

(mg/dL) |

52.0±15.0 | 52.0±15.0 | 46.5±11.2 | 0.003 |

| Diabetes (Y/N) | 722 (14.4%) | 714 (14.3%) | 8 (19.0%) | 0.38 |

| Smoking (Y/N) | 566 (11.3%) | 560 (11.2%) | 6 (14.3%) | 0.53 |

| Education a | 0.15 | |||

| less than high school | 1160 (23.1%) | 1146 (23.0%) | 14 (33.3%) | . |

| high school / equivalent |

1331 (26.5%) | 1319 (26.5%) | 12 (28.6%) | . |

| college | 1331 (26.5%) | 1321 (26.5%) | 10 (23.8%) | . |

| graduate school | 1206 (24.0%) | 1200 (24.1%) | 6 (14.3%) | . |

| Income b | 0.054 | |||

| < $25,000. | 805 (16.0%) | 798 (16.0%) | 7 (16.7%) | . |

| $25,000 to $50,000 | 2337 (46.5%) | 2313 (46.4%) | 24 (57.1%) | . |

| $50,000 to $100,000 | 924 (18.4%) | 917 (18.4%) | 7 (16.7%) | . |

| > $100,000 | 962 (19.1%) | 958 (19.2%) | 4 (9.5%) | . |

|

Mean CCA IMT

(mm) |

0.71±0.19 | 0.71±0.19 | 0.79±0.17 | 0.003 |

|

IMT Rate-of-change

(mm/year) |

0.01±0.05 | 0.01±0.05 | 0.04±0.07 | 0.051 |

|

Quartiles of IMT

rate-of-change |

0.009 | |||

| Q1 | 1257 (25.0%) | 1250 (25.1%) | 7 (16.7%) | . |

| Q2 | 1257 (25.0%) | 1250 (25.1%) | 7 (16.7%) | . |

| Q3 | 1257 (25.0%) | 1248 (25.0%) | 9 (21.4%) | . |

| Q4 | 1257 (25.0%) | 1238 (24.8%) | 19 (45.2%) | . |

|

Q4 compared to Q1,

Q2 and Q3 combined |

0.002 | |||

| Q1, 2 and 3 combined | 3771 (75.0%) | 3748 (75.2%) | 23 (54.8%) | . |

| Q4 | 1257 (25.0%) | 1238 (24.8%) | 19 (45.2%) | . |

P values estimated from unadjusted Cox regression models.

education levels as defined in the Methods section.

Income levels as defined in the Methods section. Quartiles of IMT rate-of-change: Q1: −0.367, 0.00004 mm/year; Q2: 0.00004, 0.0115 mm/year; Q3: 0.0116, 0.0264 mm/year; Q4: 0.0264, 0.472 mm/year.

After adjustment for all risk factors, significant positive associations with stroke were seen with age, systolic blood pressure and IMT rate-of-change (Table 2). HDL-Cholesterol was inversely associated with the risk of incident stroke. Ethnicity had a borderline significant association with incident stroke with lower risk for Chinese. IMT rate-of-change was significantly associated with stroke as a continuous variable with a hazards risk ratio per standard deviation of 1.23 (1.02, 1.48; 95% CL), as the upper quartile compared to the lowest quartile with a hazards risk ratio of 3.12 (1.26, 7.72; 95% CL) and as the upper quartile as compared to the combined three lower quartiles with a hazards risk ratio of 2.18 (1.07, 4.46; 95% CL).

Table 2.

Results of multivariable Cox regression models with first incident stroke as outcome without and with IMT (intima-media thickness) variables.

| Risk factors | With IMT rate-of-change |

With IMT rate-of-change and IMT |

With IMT rate-of- change Quartile / IMT |

With IMT rate-of- change upper quartile / IMT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | P- Value |

HR | P- Value |

HR | P- Value |

HR | P-Value | HR | P-Value |

| Age (Years) | 1.05 | 0.04 | 1.05 | 0.04 | 1.05 | 0.03 | 1.05 | 0.02 | 1.05 | 0.02 |

| Sex (Male) | 0.73 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.73 | 0.42 |

|

Systolic Pressure

(mm/Hg) |

1.02 | 0.0012 | 1.02 | 0.0012 | 1.02 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.007 | 1.02 | 0.001 |

|

Hypertension Medication

(Yes) |

1.56 | 0.21 | 1.57 | 0.20 | 1.60 | 0.19 | 1.66 | 0.15 | 1.63 | 0.17 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.72 | 1.00 | 0.76 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.01 |

| Diabetes (Yes) | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.97 |

| Smoking (Yes) | 1.49 | 0.37 | 1.58 | 0.30 | 1.62 | 0.29 | 1.60 | 0.30 | 1.57 | 0.31 |

| Education | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 0.67 |

| Income | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 0.47 |

| IMT (per SDEV) | . | . | . | . | 0.89 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.44 | 0.90 | 0.36 |

|

IMT rate-of-change (per

SDEV) |

. | . | 1.23 | 0.03 | 1.29 | 0.03 | . | . | . | . |

| Q2 | . | . | . | . | . | . | 1.76 | 0.29 | . | . |

| Q3 | . | . | . | . | . | . | 1.88 | 0.22 | . | . |

| Q4 | . | . | . | . | . | . | 3.12 | 0.01 | . | . |

|

Q4 as compared to Q1,

Q2 and Q3 combined |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 2.18 | 0.03 |

HR: Hazard Rate Ratio; Whites are the reference for ethnicity; SDEV: standard deviation; Education and total family income as indicated in the Methods section. Quartiles of IMT rate-of-change: Q1 (reference): −0.367, 0.00004 mm/year; Q2: 0.00004, 0.0115 mm/year; Q3: 0.0116, 0.0264 mm/year; Q4: 0.0264, 0.472 mm/year. Results are adjusted for ethnicity.

The 95% confidence limits for all hazard rates ratios are shown as supplemental tables 1 and 2.

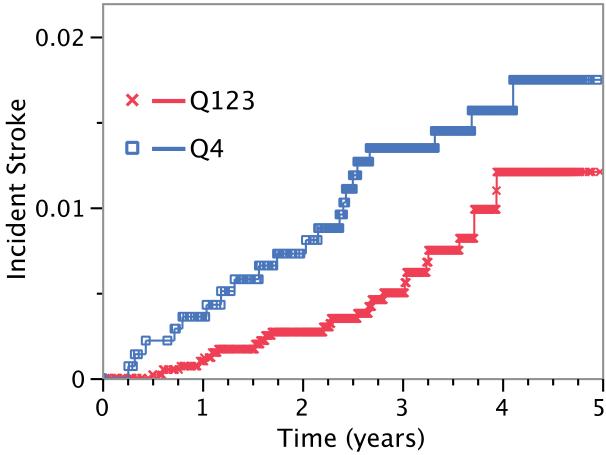

Kaplan-Meier failure curves showing results for the upper quartile versus the combination of the lower three quartiles of IMT rate-of-change are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Stroke incidence (failure Kaplan-Meier) curves for lower three quartiles of IMT progression (X) and upper quartile (square).

Clinic site, change in LDL-Cholesterol, change in HDL-Cholesterol and change in systolic blood pressure between both visits were not associated with incident stroke (data not shown).

Discussion

We have found that IMT rate-of-change is associated with incident stroke in this multi-ethnic cohort. Other risk factors positively associated with incident stroke include age, systolic blood pressure and lower HDL cholesterol levels whereas common carotid artery IMT, smoking and diabetes were not.

We conservatively set time zero for the Cox proportional hazards models at the second carotid IMT examination when IMT rate-of-change is measured and current risk factors evaluated. While this approach decreases the number of events, it reduces bias introduced by interventions instituted in response to incident events occurring during the time interval between IMT measurements.

We have found that IMT is associated with incident stroke in our unadjusted analyses but this association became non-significant after adjustment for risk factors. We believe that some of the differences between our observations and previous studies might be due to the low number of events in our population and the location where we performed IMT measurements:

The number of incident strokes in studies showing an association between CCA IMT and incident stroke is larger than ours. The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) study reported 284 incident strokes in a group of 4466 individuals over 4.7 years. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study reported on 199 ischemic strokes over 7.2 years2. The Rotterdam Study reported on 160 strokes in 5479 individual over 5.2 years9. However, the Tromso study with 397 events over 10 years of follow-up in 6584 participants did not find CCA IMT to be a consistent predictor of stroke10. We report on only 42 events over 3.2 years for 5028 individuals.

Most studies perform IMT measurements close to the carotid artery bulb11-13. In ARIC, common carotid artery IMT measurements included plaque formation in at least 7% of individuals13. By design, the MESA IMT Progression study places the site of IMT measurements lower in the common carotid artery in an area free of plaque (Figure 1). We are likely focusing on associations between stroke and a pathologic process distinct from plaque formation14.

Stroke risk factors include prevalent cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy by electrocardiographic criteria, age, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, cigarette smoking15. Prevalent cardiovascular disease and atrial fibrillation are absent in our cohort. Left ventricular hypertrophy was present in 56 individuals (data not shown) and only one individual had an incident stroke. We observe a positive association of incident stroke with age and systolic blood pressure as reported in the Framingham Heart Study15 and ARIC2. Lack of significance for diabetes and smoking is likely due to a lack of statistical power secondary to the small number of stroke events. The positive association between stroke and lower HDL cholesterol levels is consistent with high HDL-Cholesterol levels having a protective effect for cardiovascular disease.

A limitation of our study is the inherent variability of IMT measurements since we perform IMT progression measurements at six separate centers without the rigid enrollment criteria used in drug intervention trials where change in IMT serves as outcome16-18. This might have increased the variability of the measurements in a global fashion but did not affect our findings since clinic site did not predict events.

Change in plaque area might be a better predictor of stroke since it has better reproducibility19, 20 than CCA IMT and given that plaque area itself is associated with stroke10. Published data from one study has shown an association between change in plaque area and stroke20.

Because of low event rate (n =1) for Chinese participants (Table 1) we adjusted our models for ethnicity but did not investigate ethnic specific hazards ratios.

In a literature review, we found one study that addressed IMT rate-of-change as a risk factor for stroke: The European Lacipidine Study on Atherosclerosis (ELSA). The ELSA study investigated the associations of anti-hypertensive therapy on IMT progression and cardiovascular outcomes5. ELSA reported a positive association between baseline IMT and stroke but not for change in IMT5.

Summary

We conclude that common carotid artery IMT rate-of-change is associated with stroke in a cohort free of prevalent cardiovascular disease and atrial fibrillation at baseline. Given the inherent variability of IMT and IMT rate-of-change measurements, these results require confirmation in other cohort studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the investigators, the staff, and the participants of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Sources of Funding:

This research was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95165 and N01-HC-95167 as well as R01 HL069003 and R01 HL081352 (Dr Polak).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Daniel H. O’Leary owns stock in Medpace, Inc.; Michael J Pencina is a DSMB member for Abbott.

Subject codes: 8 Epidemiology; 13 Cerebrovascular Disease/stroke; 66 Risk factors for stroke; 135 Risk factors

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bots ML, Hoes AW, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Common carotid intima-media thickness and risk of stroke and myocardial infarction: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 1997;96:1432–1437. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Clegg LX, Sharrett AR, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, et al. Carotid wall thickness is predictive of incident clinical stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151:478–487. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.OLeary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson SK, Jr., Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosvall M, Janzon L, Berglund G, Engstrom G, Hedblad B. Incidence of stroke is related to carotid IMT even in the absence of plaque. Atherosclerosis. 2005;179:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanchetti A, Hennig M, Hollweck R, Bond G, Tang R, Cuspidi C, et al. Baseline values but not treatment-induced changes in carotid intima-media thickness predict incident cardiovascular events in treated hypertensive patients: findings in the European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis (ELSA) Circulation. 2009;120:1084–1090. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.773119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Agostino RB, Sr., Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genuth S, Alberti KGMM, Bennett P, Buse J, Defronzo R, Kahn R, et al. Expert Committee on the D, Classification of Diabetes M. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160–3167. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3160. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollander M, Koudstaal PJ, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Incidence, risk, and case fatality of first ever stroke in the elderly population. The Rotterdam Study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2003;74:317–321. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathiesen EB, Johnsen SH, Wilsgaard T, Bonaa KH, Lochen M-L, Njolstad I. Carotid plaque area and intima-media thickness in prediction of first-ever ischemic stroke: a 10-year follow-up of 6584 men and women: the tromso study. Stroke. 2011;42:972–978. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, Rosvall M, Sitzer M. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2007;115:459–467. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folsom AR, Kronmal RA, Detrano RC, O’Leary DH, Bild DE, Bluemke DA, et al. Coronary artery calcification compared with carotid intima-media thickness in the prediction of cardiovascular disease incidence: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168:1333–1339. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li R, Duncan BB, Metcalf PA, Crouse JR, 3rd, Sharrett AR, Tyroler HA, et al. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators B-mode-detected carotid artery plaque in a general population. Stroke. 1994;25:2377–2383. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.12.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalager S, Paaske WP, Kristensen IB, Laurberg JM, Falk E. Artery-related differences in atherosclerosis expression: implications for atherogenesis and dynamics in intima-media thickness. Stroke. 2007;38:2698–2705. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espeland MA, Craven TE, Riley WA, Corson J, Romont A, Furberg CD, Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Progression Study Research Group Reliability of longitudinal ultrasonographic measurements of carotid intimal-medial thicknesses. Stroke. 1996;27:480–485. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedblad B, Wikstrand J, Janzon L, Wedel H, Berglund G. Low-dose metoprolol CR/XL and fluvastatin slow progression of carotid intima-media thickness: Main results from the Beta-Blocker Cholesterol-Lowering Asymptomatic Plaque Study (BCAPS) Circulation. 2001;103:1721–1726. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smilde TJ, van Wissen S, Wollersheim H, Trip MD, Kastelein JJ, Stalenhoef AF. Effect of aggressive versus conventional lipid lowering on atherosclerosis progression in familial hypercholesterolaemia (ASAP): a prospective, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2001;357:577–581. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shai I, Spence JD, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Parraga G, Rudich A, et al. Group D. Dietary intervention to reverse carotid atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2010;121:1200–1208. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.879254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spence JD, Eliasziw M, DiCicco M, Hackam DG, Galil R, Lohmann T. Carotid plaque area: a tool for targeting and evaluating vascular preventive therapy. Stroke. 2002;33:2916–2922. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000042207.16156.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.