Abstract

In phyllosphere microbiology, the distribution of resources available to bacterial colonizers of leaf surfaces is generally understood to be very heterogeneous. However, there is little quantitative understanding of the mechanisms that underlie this heterogeneity. Here, we tested the hypothesis that different parts of the cuticle vary in the degree to which they allow diffusion of the leaf sugar fructose to the surface. To this end, individual, isolated cuticles of poplar leaves were each analyzed for two properties: (1) the permeability for fructose, which involved measurement of diffused fructose by gas chromatography and flame ionization detection (GC–FID), and (2) the number and size of fructose-permeable sites on the cuticle, which was achieved using a green-fluorescent protein (GFP)-based bacterial bioreporter for fructose. Bulk flux measurements revealed an average permeance P of 3.39 × 10−9 ms−1, while the bioreporter showed that most of the leaching fructose was clustered to sites around the base of shed trichomes, which accounted for only 0.37% of the surface of the cuticles under study. Combined, the GC–FID and GFP measurements allowed us to calculate an apparent rate of fructose diffusion at these preferential leaching sites of 9.15 × 10−7 ms−1. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first successful attempt to quantify cuticle permeability at a resolution that is most relevant to bacterial colonizers of plant leaves. The estimates for P at different spatial scales will be useful for future models that aim to explain and predict temporal and spatial patterns of bacterial colonization of plant foliage based on lateral heterogeneity in sugar permeability of the leaf cuticle.

Keywords: poplar, Populus x canescens, aqueous pores, phyllosphere, Erwinia herbicola, fructose, gas chromatography

Introduction

For terrestrial plants, the cuticle represents the direct interface between aerial plant parts and the atmosphere. It predominantly consists of cutin, an esterified aliphatic polymer (Kolattukudy, 1980) that is impregnated and overlaid by intra- and epi-cuticular waxes, respectively (Jetter and Schäffer, 2001). The thickness of plant cuticles ranges from 30 nm for Arabidopsis thaliana leaves to 30 μm for Malus domestica fruit (Schreiber and Schönherr, 2009). From a plant perspective, the cuticular membrane (CM) plays a pivotal role in preventing the loss of water, minerals, and nutrients, and in protecting the plant against pathogenic attacks (Riederer and Müller, 2006). The hydrophobic nature of plant cuticles correlates with a limited permeability for polar substances such as water and ions (Schönherr and Schreiber, 2004). By comparison, plant cuticles are less permeable for water than synthetic polymers such as polyethylene or polypropylene of equal thickness (Riederer and Schreiber, 2001). Another difference between plant cuticles and synthetic membranes is that the former are characterized by a pronounced lateral heterogeneity. Plant leaves are oftentimes decorated with features such as trichomes, gland cells, and stomata, (Schlegel et al., 2005; Schreiber, 2005), and these structures may differ substantially in the thickness and wax composition of the cuticle that covers them, as shown recently for trichomes of a pubescent peach fruit variety (Fernández et al., 2011). Also, the leaf cuticle tends to be thicker over anticlinal cell walls between epidermal cells than on top of epidermal cells (Jeffree, 2007).

Despite the design of the leaf cuticle to prevent the loss of water and nutrients, it has long been recognized that plant leaves may lose measurable amounts of carbohydrates and other substances to the leaf surface through a process called leaching (Tukey, 1966). These “leachates” are used by microorganisms that inhabit the leaf surface, or phyllosphere (Andrews and Harris, 2000). For many of these bacteria, yeasts, and fungi, the phyllosphere is considered a carbon-limited environment (Wilson and Lindow, 1995; Wilson et al., 1995), which means that these microbes rely on a constant flux of photosynthates such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose from the leaf interior. A recent study (van der Wal and Leveau, 2011) estimated that the diffusion of fructose through the isolated CM of Juglans regia (walnut) leaves is sufficient to sustain microbial populations as they are typically found in the phyllosphere. Others have come to the same conclusion using isolated CMs of Prunus laurocerasus, or cherry laurel (Krimm, 2005).

So far, the quantification of sugar diffusion across plant leaf cuticles has been restricted mainly to bulk measurements integrating sugar flux over entire leaves (Tukey, 1966; Mercier and Lindow, 2000) or over isolated CM disks (Schönherr, 1976; Krimm, 2005; van der Wal and Leveau, 2011). Estimations of sugar permeance at smaller scales, for example the scale of individual bacteria, are not available, although the use of fluorescent bioreporters has previously revealed the existence of “hotspots” of fructose availability to bacteria on the plant leaf surface (Leveau and Lindow, 2001; Krimm, 2005). Possibly, such sites represent areas where the cuticle is more permeable than in other locales on the leaf surface. A quantitative understanding of this lateral heterogeneity in carbohydrate permeance at the micrometer scale will improve our ability to explain and predict foliar growth of microorganisms, including those that are plant pathogenic.

To achieve such understanding, we employed an integrated approach that combined bulk flux measurements of fructose across disks of isolated cuticles with the analysis of single-cell bioreporter information on local fructose availability on the same set of cuticles. The bioreporter was based on Erwinia herbicola 299 (Eh299), a natural colonizer of the phyllosphere (Brandl and Lindow, 1996) which has been used in many phyllosphere studies (Brandl et al., 2001; Leveau and Lindow, 2001; Krimm, 2005; Remus-Emsermann and Leveau, 2010; van der Wal and Leveau, 2011). Eh299 is equipped with a construct allowing expression of the green-fluorescent protein (GFP) in response to fructose exposure (Leveau and Lindow, 2001). On the plant side, we chose to work with CMs isolated from the adaxial, astomatous, mature leaves of poplar (Populus x canescens). Being a model system for the molecular biology of trees (Bradshaw et al., 2000), the industrial production of wood, and phytoremediation applications (Stanton et al., 2002), poplar also has played an important role in research on the permeability of plant leaf cuticles for ions (Schönherr and Schreiber, 2004; Schreiber et al., 2006). Experiments with isolated leaf cuticles of Populus x canescens suggested the existence of aqueous pores in the cuticle, of sufficient hydrophilicity to allow the passage of ions such as Ca2+, Cl−, and Ag+ (Schönherr and Schreiber, 2004; Schreiber et al., 2006). As leaves of Populus x canescens mature, trichomes are shed, and ion passage (more specifically, the formation of microscopically visible AgCl crystals) was most abundantly found to occur at the bases of these shed trichomes. It was ruled out that shedding resulted in the formation of holes; instead, the authors argued for the existence of polar pathways, also referred to as aqueous pores (Schönherr and Schreiber, 2004) at these sites. This finding challenged the model of slow diffusion of polar substances through a laterally homogeneous cuticle in favor of a model featuring much more lateral heterogeneity (Franke, 1967; Schreiber and Schönherr, 2009). For a fundamental understanding of microbial phyllosphere colonization, this lateral heterogeneity is of great importance, because it could be used to explain the non-random patterns of leaf colonization by bacteria (Monier and Lindow, 2004) In the study presented here, we confirm that shed trichome sites are more permeable for sugars and provide quantitative estimates for the permeance and frequency of sugar-permeable sites on the poplar leaf surface.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of cuticular membranes

Isolation of CMs was conducted as described elsewhere (Schreiber and Schönherr, 2009). In short, it involved the digestion of 20-mm diameter disks of Populus x canescens (Aiton) Sm. leaves harvested in Spring 2002 near Sarstedt, Germany, with 2% cellulase and pectinase in 0.01 M citric acid buffer adjusted to pH 3–4 with KOH. To prevent growth of microorganisms, NaN3 was added to the solution at a final concentration of 1 mM. After complete digestion, isolated CMs were flattened with compressed air on Teflon disks and stored at room temperature and low ambient humidity.

Measuring of fructose bulk flux by gas chromatography and flame ionization detection

To measure the bulk flux of fructose over cuticles, cylindrical stainless steel chambers were used as described in Schreiber and Schönherr (2009). The chambers (Figure 1) consisted of a donor-chamber, filled with 1 mL of a 180 g L−1 solution of fructose, and a receiver-chamber filled with deionized water. Both donor and receiver had an inner diameter of 1.2 cm and were equipped with lockable sampling holes to allow sampling and exchange of solutions with a syringe. With their physiological outside facing the receiver-chamber, isolated CMs were mounted on top of the donor-chamber ring and sealed with high vacuum silicon grease to the receiver-chamber. The chambers were placed on a rolling bench at 28°C and samples were taken from the receiver-chamber after 5 and 24 h. Before analysis of these samples by GC/FID (see below), we tested 100 μL of each for fructose using 20 μL Benedict’s reagent (Benedict, 1909) to verify the integrity of the CMs and the integrity of the chambers with mounted CMs. Those CMs or chambers that were found to be leaky because they had similar fructose concentrations in donor and receiver compartments after 5 h were discarded and not used for further analysis. Receiver samples harvested from intact CMs and chambers were supplemented with 3 μg xylitol to serve as an internal standard, dried under constant N2-flow at 70°C, derivatized to trimethylsilyl-ethers by adding 30 μL of the catalyst Pyridine and 30 μL of Bis(trimethylsilyl)-trifluoracetamide and incubated for 40 min at 70°C. Fructose concentration was determined by gas chromatography and flame ionization detection (GC–FID; 5890 Series II Plus, HP, Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany), equipped with a dimethylpolysiloxane column (DB1 GC column, 30 m × 0.32 mm, 0.1 μm, J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA). One microliter of each sample was injected. H2 flow was set to 37 kpa. The initial temperature was 65°C for 3 min, after which the temperature was raised at a rate of 8°C per min to a temperature of 240°C, after which the rate was increased by 12°C per min to a final temperature of 310°C for 35 min. Data analysis was performed with GC ChemStation [Rev. B.03.02 (341), Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany]. Permeances were calculated using the following equation (Schreiber et al., 2006): P = F/(AxΔc). Fructose flow F (g s−1) was obtained from the regression line fitted to the points that were obtained by plotting the amount of fructose (in grams) in the receiver-chamber as a function of time, while A (m2) represents the area of exposed cuticle (1.13 × 10−4 m2) and Δc (g m−3) the difference in fructose concentration between the receiver and donor compartment (i.e., 180 g L−1 or 1.8 × 105 g per m3).

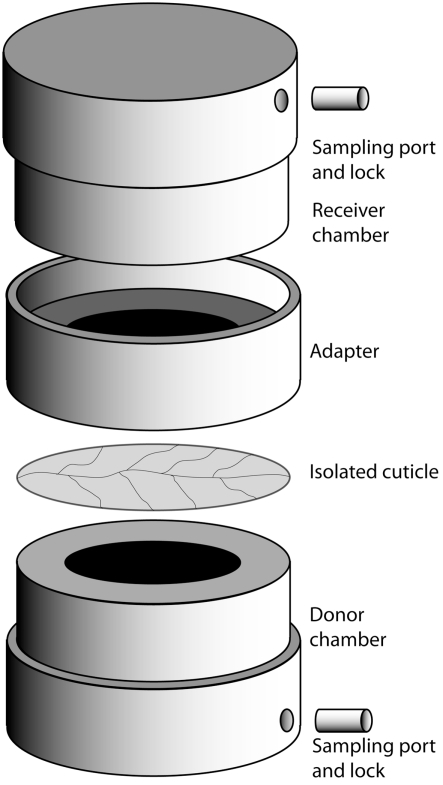

Figure 1.

Setup of the cuticle diffusion chamber. See [Measuring of fructose bulk flux by gas chromatography and flame ionization detection (GC–FID)] for details.

Inoculation of isolated CMs with bacteria

To measure localized diffusion of fructose, the receiver-chambers were unmounted, the donor-chambers were emptied, and the outside and inside of the CMs were washed with deionized water. The donor-chamber was refilled with 1 mL of an 18 g L−1 fructose solution. Cells of Eh299R carrying (pPfruB-gfp[AAV]; Leveau and Lindow, 2001) were grown overnight on LB agar plates supplemented with 50 ng kanamycin mL−1 at 30°C, spun down for 10 min at 3000×g, washed twice in sterile water, and subsequently diluted with sterile water to an optical density of 1 at 600 nm, which corresponds to approximately 4 × 108 bacterial colony forming units mL−1. Plasmid (pPfruB-gfp[AAV]) confers resistance to kanamycin and codes for the expression of a short-lived version of the GFP[AAV] under the control of the fructose-responsive fruB promoter (Leveau and Lindow, 2001). CMs were inoculated by pipetting 400 μL of this bacterial suspension on the physiological outer side of the cuticle as described by Knoll and Schreiber (2004). Diffusion chambers were incubated with the inoculated side facing up for 6 h at high relative humidity and 28°C to facilitate adhesion of bacteria to the CM. Subsequently the bacterial suspension was carefully removed by pipetting and drying at room humidity for not more than 5 min. Next, the setup was transferred into a high humidity chamber and incubated at 28°C for 16 h.

Fluorescence microscopy and image analysis

For analysis of inoculated cuticles by fluorescence microscopy and to reveal the location of reporter bacteria responding to the local availability of fructose, the donor solution was removed and a 10 μL droplet of 75% glycerol supplemented with DAPI, to counterstain all bacteria (whether they were reporting fructose or not), was applied to the center of the inoculated side of the cuticle and covered by a cover slip. Microscopy was performed using a Zeiss Axioplan stereomicroscope at 400-fold magnification and two filter sets: BP365/FT395/LP397 (Zeiss filter set 1) for visualization of DAPI-stained cells and leaf autofluorescence, and 450-490/FT510/515-565 (Zeiss filter set 10) for visualization of bacteria expressing GFP. Images were taken in gray scale mode with a DMX1200 charged coupled device (Nikon Corporation, Japan) and the Software Act-1 version 2.70 (Nikon Corporation, Japan). Images were analyzed with the software package ImageJ 1.45b (Abramoff et al., 2004) by creating pseudo-RGB images from photographs taken from the same area of the cuticle using the different filter sets. The area covered by green-fluorescent bacteria was determined using ImageJ’s measurement tools.

Results

Estimating fructose diffusion across isolated Populus x canescens cuticles

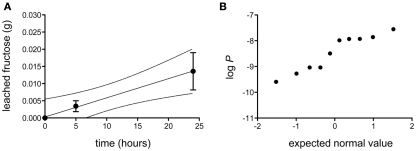

The bulk permeance of 10 individual CMs from poplar leaves was analyzed using a two-compartment experimental setup (Figure 1) that allowed the measurement of fructose diffusion from a donor compartment with a constant high fructose concentration across an isolated cuticle into a receiver compartment. Fructose abundances in the receiver compartment were quantified by gas chromatography and plotted as a function of time (Figure 2A). From the slope of the best-fit line through these points, bulk permeances of Populus x canescens CMs for fructose were calculated as ranging from 2.54 × 10−10 to 2.78 × 10−8 m s−1. Values were log-normally distributed around an average log P of −8.46 ± 0.67, which back-transforms to an average P of 3.39 × 10−9 m s−1 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Diffusion of fructose across isolated Populus x canescens leaf cuticles. (A) Accumulation of fructose (in grams) as a function of time at a donor concentration of 0.18 g mL−1. Shown is the linear regression (r2 = 0.99) with 95% confidence intervals (broken lines) of the mean (n = 10) diffusion of fructose over Populus x canescens leaf cuticles. Error-bars represent the standard error of measurement. (B) Probability plot of the log-transformed fructose permeability (P, in ms−1) of individual Populus x canescens CMs. The dataset passed the D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus test for normality (P = 0.28).

Frequency and size of fructose-permeable sites on Populus x canescens cuticular membranes

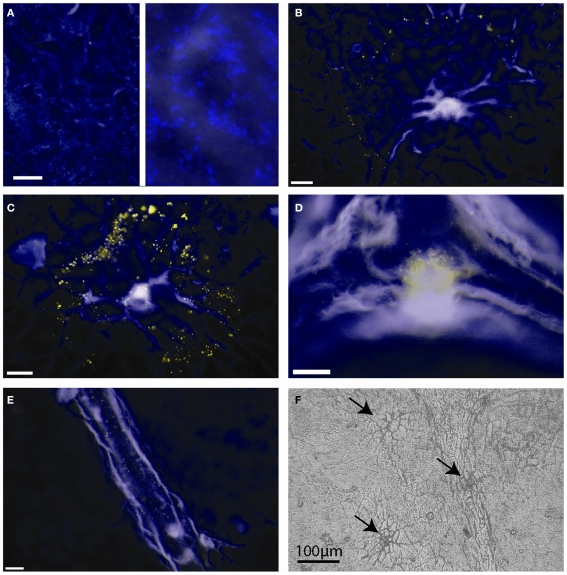

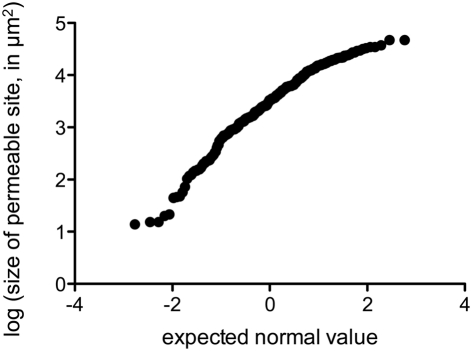

We performed fluorescence microscopy analysis on three CMs that immediately after the bulk flux measurements (see above) were exposed to the bacterial bioreporter Eh299R(pPfruB-gfp[AAV]) which responds to the presence of fructose by producing green fluorescence. The inoculation resulted in a homogeneous and random distribution of bacteria on the CMs as shown by DAPI counterstaining (Figure 3A). In contrast, the distribution of DAPI-stained cells that also were green-fluorescent was not random. Many occurred as part of circle- or ring-shaped clusters of different diameters (Figures 3B–E). The sizes of these clusters from three CMs were measured and found to be log-normally distributed (Figure 4), with many small clusters and few large clusters. The largest site covered by green-fluorescent bacteria was 4.7 × 104 μm2. Values were distributed around a log average of 3.42 ± 0.74 which back-transforms to an average size of 2.62 × 103 μm2.

Figure 3.

Green-fluorescent protein-based bioreporting of fructose availability on isolated Populus x canescens cuticles. (A–E) Epifluorescent images of Populus x canescens CMs inoculated with Eh299(pPfruB-gfp[AAV]). White scale bars represent 20 μm. Images are pseudo-colored merges of DAPI (blue) and GFP (green) channels; when fluorescence occurred in both channels the visible color is yellow. The blue channel mainly shows autofluorescence of the CM and DAPI counterstained, non-fructose reporting bacteria. (A) Area with many bacterial bioreporter cells but none that fluoresce to indicate exposure to fructose; the right-hand panel is a magnification of the photograph shown on the left-hand site, to show individual DAPI-stained bacteria. (B–D) Typical arrangements of bioreporting bacteria on isolated Populus x canescens CMs. (F) Light microscopy image of a Populus x canescens CM. Arrows point to sites with shed-off trichomes.

Figure 4.

Probability plot of the log-transformed size of fructose-permeable sites (in μm2) found on enzymatically isolated Populus x canescens CMs. Data points were derived and pooled from three individual CMs.

The majority (79%) of clusters of green-fluorescent bacteria were associated with sites of shed trichomes (e.g., Figures 3B,C,F). Thus, these structures appeared to be the main sites of fructose diffusion. We determined that 1 cm2 of the Populus x canescens leaf cuticles we used contained on average 138 ± 67 shed trichome sites. Assuming a sugar-permeable area of 2.62 × 103 μm2 for each of these (see above), we can calculate that only 0.37% of the leaf cuticle surface allowed diffusion of fructose high enough to induce GFP expression. Correspondingly, the permeance of the Populus x canescens CM at these sites would be 100/0.37 = 270 times higher than our bulk estimate, i.e., 270 × 3.39 × 10−9 = 9.15 × 10−7 m s−1.

Discussion

The GC–FID-based detection method used here allowed us to determine that the average bulk permeance of Populus x canescens CMs for fructose was one order of magnitude higher than that reported for isolated CMs of Juglans regia, i.e., 2.79 × 10−10 m s−1 (van der Wal and Leveau, 2011), but two orders of magnitude higher than Prunus laurocerasus, i.e., 6.64 × 10−11 m s−1 (Krimm, 2005). This is consistent with earlier findings (Kirsch et al., 1997) that cuticles of evergreens such as P. laurocerasus are less permeable than cuticles of deciduous trees such as Populus x canescens and J. regia.

Aqueous pores are thought to be made up of hydrated polar functional groups in the cuticle (Chamel et al., 1991). Values reported for aqueous pore sizes of plant leaf cuticles were determined for a series of isolated cuticles and showed average radii of 5 Å estimated from trans-cuticular Ag+- and Cl−-diffusion (Schreiber et al., 2006). The hydrodynamic radius of a fructose molecule has been calculated as 3.61 Å (Ribeiro et al., 2006), thus permeance of fructose through these pores should be possible. Interestingly, the estimates derived from our study can be used to get a better appreciation for the density of aqueous pores. The permeance P of an individual pore can be calculated from diffusion coefficient D for fructose in water, i.e., 7.44 × 10−10 m2 s−1 at 30°C (Ribeiro et al., 2006) and the length L of the path along which diffusion takes place. If we assume that the latter is approximated by the thickness of the cuticle, 2.8 × 10−6 m (Todeschini et al., 2011), P can be calculated as D/L or 2.66 × 10−4 m s−1. This value is 7.84 × 104 times higher than the bulk permeance we measured for the poplar cuticle. If diffusion of fructose only takes place through aqueous pores we can now estimate the relative area of the cuticle that is effectively permeable to fructose to be 100%/7.84 × 104 = 1.28 × 10−3%. Assuming a pore radius of 5 Å, i.e., a pore area of 2.5 × 10−19 m2, the total number of pores per m2 can be calculated as 5.1 × 1013, which is close to the value of 3.5 × 1014 to 2 × 1015 pores per m2 reported for isolated Citrus aurantium cuticles (Schreiber and Schönherr, 2009). Assuming that pores only occur at permeable sites (i.e., the basis of trichomes), the density of aqueous pores at these sites may be calculated as 270 times higher, i.e., 1.38 × 1016 aqueous pores per m2. However, these calculated values have to be used with caution, and will need to be verified in future studies.

Our results with the GFP-based fructose bioreporter indicate that the poplar leaf cuticle features sites that are more permeable to fructose than most other sites on the cuticle. These preferential sites seemed to be clustered around shed trichomes. It has been shown that the base of plant leaf trichomes can be heavily cutinized (Fernández et al., 2011), and so our findings and those of others (Schreiber et al., 2006) may be explained by assuming that the observed increased permeability is specific to shed trichomes, representing sites that are structurally less integer than non-modified cuticular areas, as has been suggested for lenticels on fruit (Glenn and Poovaiah, 1985). In the absence of measurement of cutin and waxes, however, this remains speculative and needs to be confirmed in future experiments.

The predominant presence of sugar-diffusible sites around trichomes on the Populus x canescens cuticle is in good agreement with general observations that bacterial leaf colonizers often establish large populations around the base of trichomes (Monier and Lindow, 2004). Trichomes have also been identified as sites where sugars are commonly and abundantly available to leaf-colonizing bacteria (Leveau and Lindow, 2001). Heterogeneity in the availability of nutrients on the leaf surface is consistent with the recent observation that bacterial immigrants to the bean phyllosphere experience very different fates (Remus-Emsermann and Leveau, 2010): while most cells divided a few times upon arrival, a few divided many more times. The latter was explained by assuming that those cells landed in sites of high nutrients access. Plants other than Populus x canescens, for example Vicia faba and Phaseolus vulgaris posses aqueous pores not only around trichomes but also associated with other leaf features, such as guard cells of stomata, anticlinal cell walls, and glandular trichomes (Schlegel et al., 2005; Schreiber and Schönherr, 2009). Based on this difference, our prediction would be that patterns of bacterial colonization on leaves from these plants would be different from those observed for poplar.

In conclusion, the poplar leaf cuticle features sites that are more permeable to fructose than most other sites on the cuticle. These preferential sites seem to be clustered around shed trichomes. The estimated values for diffusion rates at these sites provide the first numerical estimation of micrometer scale carbohydrate availability in the phyllosphere. They will help to explain microbial growth patterns in the phyllosphere and contribute to modeling of microbial growth in the phyllosphere, which so far has been hampered by experimentally derived estimates of carbohydrate diffusion and availability at scales that matter most to potential colonizers of the phyllosphere.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research (NWO) in the form of a personal VIDI grant to Johan H. J. Leveau and by the German Research Foundation (DFG) to Lukas Schreiber. This is NIOO publication 5101.

References

- Abramoff M. D., Magelhaes P. J., Ram S. J. (2004). Image processing with imageJ. Biophotonics Int. 11, 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. H., Harris R. F. (2000). The ecology and biogeography of microorganisms of plant surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 38, 145–180 10.1146/annurev.phyto.38.1.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict S. R. (1909). A reagent for the detection of reducing sugars. J. Biol. Chem. 5, 485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw H. D., Ceulemans R., Davis J., Stettler R. (2000). Emerging model systems in plant biology: poplar (populus) as a model forest tree. J. Plant Growth Regul. 19, 306–313 10.1007/s003440000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl M. T., Lindow S. E. (1996). Cloning and characterization of a locus encoding an indolepyruvate decarboxylase involved in indole-3-acetic acid synthesis in Erwinia herbicola. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 4121–4128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl M. T., Quinones B., Lindow S. E. (2001). Heterogeneous transcription of an indoleacetic acid biosynthetic gene in Erwinia herbicola on plant surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3454–3459 10.1073/pnas.061014498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamel A., Pineri M., Escoubes M. (1991). Quantitative determination of water sorption by plant cuticles. Plant Cell Environ. 14, 87–95 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1991.tb01374.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández V., Khayet M., Montero-Prado P., Heredia-Guerrero J. A., Liakopoulos G., Karabourniotis G., Del Río V., Domínguez E., Tacchini I., Nerín C., Val J., Heredia A. (2011). New insights into the properties of pubescent surfaces: the peach fruit (Prunus persica Batsch) as a model. Plant Physiol. 156, 2098–2108 10.1104/pp.111.176305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke W. (1967). Mechanisms of foliar penetration of solutions. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 18, 281–300 10.1146/annurev.pp.18.060167.001433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn G. M., Poovaiah B. W. (1985). Cuticular permeability to calcium compounds in golden delicious apple fruit. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 110, 192–195 [Google Scholar]

- Jeffree C. E. (2007). “The fine structure of the plant cuticle,” in Annual Plant Reviews, Vol. 23, Biology of the Plant Cuticle, eds Riederer M., Müller C. (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.), 11–125 [Google Scholar]

- Jetter R., Schäffer S. (2001). Chemical composition of the Prunus laurocerasus leaf surface. Dynamic changes of the epicuticular wax film during leaf development. Plant Physiol. 126, 1725–1737 10.1104/pp.126.4.1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch T., Kaffarnik F., Riederer M., Schreiber L. (1997). Cuticular permeability of the three tree species Prunus laurocerasus L., Ginkgo biloba L., and Juglans regia L.: comparative investigation of the transport properties of intact leaves, isolated cuticles and reconstituted cuticular waxes. J. Exp. Bot. 48, 1035–1045 10.1093/jxb/48.5.1035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll D., Schreiber L. (2004). Methods for Analysing the Interactions between Epiphytic Microorganisms and Leaf Cuticles. Berlin: Springer-Verlag [Google Scholar]

- Kolattukudy P. E. (1980). Bio-polyester membranes of plants – cutin and suberin. Science 208, 990–1000 10.1126/science.208.4447.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimm U. (2005). Untersuchungen zur Interaktion epiphyller Bakterien mit Blattoberflächen und Veränderungen in der Phyllosphäre während der Vegetationsperiode. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät., Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms- Universität Bonn, Bonn [Google Scholar]

- Leveau J. H. J., Lindow S. E. (2001). Appetite of an epiphyte: quantitative monitoring of bacterial sugar consumption in the phyllosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3446–3453 10.1073/pnas.061629598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier J., Lindow S. E. (2000). Role of leaf surface sugars in colonization of plants by bacterial epiphytes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 369–374 10.1128/AEM.66.1.369-374.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monier J. M., Lindow S. E. (2004). Frequency, size, and localization of bacterial aggregates on bean leaf surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 346–355 10.1128/AEM.70.1.346-355.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remus-Emsermann M. N. P., Leveau J. H. J. (2010). Linking environmental heterogeneity and reproductive success at single-cell resolution. Isme J. 4, 215–222 10.1038/ismej.2009.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro A. C. F., Santos C. I. A. V., Lobo V. M. M., Valente A. J. M., Prazeres P. M. R. A., Burrows H. D. (2006). Diffusion coefficients of aqueous solutions of carbohydrates as seen by Taylor dispersion technique at physiological temperature (37 degrees C). Defect Diffusion Forum 258–260, 305–309 [Google Scholar]

- Riederer M., Müller C. (eds). (2006). Biology of the Plant Cuticle. Annual Plant Reviews. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Riederer M., Schreiber L. (2001). Protecting against water loss: analysis of the barrier properties of plant cuticles. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 2023–2032 10.1093/jexbot/52.363.2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel T. K., Schönherr J., Schreiber L. (2005). Size selectivity of aqueous pores in stomatous cuticles of Vicia faba leaves. Planta 221, 648–655 10.1007/s00425-005-1480-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J. (1976). Water permeability of isolated cuticular membranes: the effect of pH and cations on diffusion, hydrodynamic permeability and size of polar pores in the cutin matrix. Planta 128, 113–126 10.1007/BF00390312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J., Schreiber L. (2004). Size selectivity of aqueous pores in astomatous cuticular membranes isolated from Populus canescens (Aiton) Sm. leaves. Planta 219, 405–411 10.1007/s00425-004-1239-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L. (2005). Polar paths of diffusion across plant cuticles: new evidence for an old hypothesis. Ann. Bot. 95, 1069–1073 10.1093/aob/mci122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L., Elshatshat S., Koch K., Lin J., Santrucek J. (2006). AgCl precipitates in isolated cuticular membranes reduce rates of cuticular transpiration. Planta 223, 283–290 10.1007/s00425-005-0084-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L., Schönherr J. (2009). Water and Solute Permeability of Plant Cuticles. Heidelberg: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B., Eaton J., Johnson J., Rice D., Schuette B., Moser B. (2002). Hybrid poplar in the Pacific Northwest: the effects of market-driven management. J. Forest. 100, 28–33 [Google Scholar]

- Todeschini V., Lingua G., D’Agostino G., Carniato F., Roccotiello E., Berta G. (2011). Effects of high zinc concentration on poplar leaves: a morphological and biochemical study. Environ. Exp. Bot. 71, 50–56 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.10.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tukey H. B., Jr. (1966). Leaching of metabolites from above-ground plant parts and its implications. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 93, 385–4015943196 [Google Scholar]

- van der Wal A., Leveau J. H. J. (2011). Modelling sugar diffusion across plant leaf cuticles: the effect of free water on substrate availability to phyllosphere bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 792–797 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M., Lindow S. (1995). Enhanced epiphytic coexistence of near-isogenic salicylate-catabolizing and non-salicylate-catabolizing Pseudomonas putida strains after exogenous salicylate application. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 1073–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M., Savka M. A., Hwang I., Farrand S. K., Lindow S. E. (1995). Altered epiphytic colonization of mannityl opine-producing transgenic tobacco plants by a mannityl opine-catabolizing strain of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 2151–2158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]