Abstract

Thalassemia is the most common inherited single-gene (autosomal recessive) disorder in the world. Scientists worldwide predict that thalassemia will become a considerable health issue in the next century. It is a new disease entity for Ayurvedic medicine, and hence, it is called Anukta Vyadhi in Ayurveda; but we can understand it by careful scrutiny of the clinical presentation and the investigation results described in the available literature. Modern medical management is aimed at maintaining the hemoglobin level at 10 – 12 g/dl. A post-transfusion hemoglobin level of 9.5 g/dl is said to be sufficient to maintain active life. Thus, blood transfusion therapy is the only treatment, but it can result in hemosiderosis (iron overload), a complication with a fatal outcome. The transfusional iron overload is compounded by increased intestinal absorption of iron. The most important factors associated with survival, and also those deciding the outcome of bone marrow transplant (the only curative therapy) are, age at which chelation therapy is introduced and the success with which serum ferritin is maintained below 2500 ng/ml. Iron chelators used in modern medicine to achieve this goal are expensive and associated with side effects, and hence, associated with poor adherence to the treatment. The present study is an endeavor to explore the efficacy of Triphaladi Avaleha as an iron chelator in the management of thalassemia, in comparison to a control group managed by routine modern therapy.

Keywords: Thalassemia, Anukta Vyadhi, Hemosiderosis, Triphaladi Avaleha, Serum Ferritin

Introduction

The thalassemias are inherited disorders of α- or β-globin biosynthesis caused by mutations in the globin gene.[1] The reduced supply of globin diminishes the production of hemoglobin tetramers, causing hypochromia and microcytosis. The key feature is the fact that there is globin chain imbalance. This unbalanced chain accumulation dominates the clinical phenotype. The abnormal tetramers are not as lethal, but lead to extravascular hemolysis, disrupting maturation of the red cells in the bone marrow, thereby resulting in ineffective erythropoesis and a hyperactive bone marrow.[2] The consequent iron overload also contributes and complicates the outcome of the disease.

As per the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate, 4.5% of the world's population are carriers of hemoglobinopathies. Nearly 180 – 200 million people in the world carry the gene for β-thalassemia. One lakh children are yearly born world over with the homozygous state for thalassemia.[3] The frequency of the thalassemia gene in the Indian population varies from 0 to 17% in different ethnic groups, the average being 3%.[1] Around 20 – 30 million people in India are carriers for thalassemia, and 8 – 10 thousand children are born with thalassemia every year in India.[5] According to a study conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) the frequency of the thalassemia trait is 3 – 18% in Northern India and 1 – 3% in Southern India. The highest frequency of the β-thalassemia trait is reported from Gujarat, followed by Punjab, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra.[6] Thus, every year some 10000 children with thalassemia major are born in India; this constitutes 10% of the total number in the world. One out of every eight carriers of thalassemia worldwide lives in India. This disease is of particular importance in developing countries like India, where it increases the burden on the healthcare delivery system.[7]

Modern medical management in thalassemia is aimed at maintaining the hemoglobin level at 10 – 12 g/dl.[8] A post-transfusion hemoglobin level of 9.5 g/dl is said to be sufficient to maintain active life.[2] To achieve this, repeated blood transfusion is the only treatment, but this results in hemosiderosis (iron overload) as a complication. The total iron content of the body is 4.5 g. A unit of packed red blood cells (RBCs) contains 250 – 300 mg of iron, that is, 1 mg/ml. Thus, iron assimilated by a single transfusion of two units of packed RBCs is equivalent to one to two years of the normal intake of iron. A patient who receives more than 100 units of packed RBCs usually develops hemosiderosis.[9] The enhanced iron absorption has been confirmed by direct measurement.[10] The transfused RBCs depend on anaerobic respiration for adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP) synthesis. They are also exposed to constant oxidative stress. As RBCs lacks a nucleus, the damaged components are not replaced with newer ones. The splenomegaly (hyperplenism) that is present worsens the problem. On account of this, the RBCs are under constant wear and tear while passing through the capillaries.[11]

The most important factors associated with survival (and with the outcome of bone marrow transplant) are the age at which chelation therapy is introduced and the success with which serum ferritin is maintained below 2500 ng/ ml.[10] Iron chelators used in modern medicine are expensive and associated with side effects like growth retardation, visual and auditory toxicity, cataracts (with desferrioxamine), arthropathy, and agranulocytosis (with deferiprone).

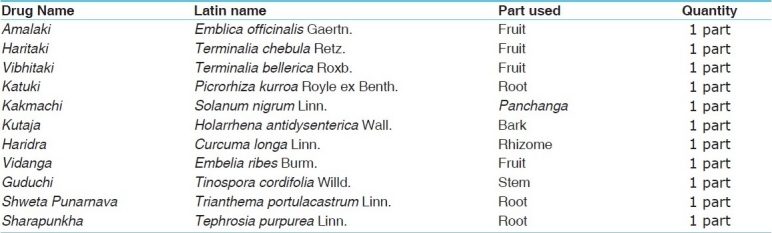

The present study is an endeavor to explore the efficacy of Triphaladi Avaleha in the management of thalassemia, as compared to a control group managed by routine modern therapy. All the drugs selected for the present study are very simple, nontoxic, and easily available [Table 1]. These drugs are used in Lohashodhana, Lohamarana, Lohasevanajanya Vikara, Yakrita, and Pleeha Vikara (Mula Sthana of Raktavaha Srotas) and are described in the Triphaladi Kiratadi Gana in Rasa Ratna Samuchaya.[12] These can be used as iron chelators and thus help to decrease the overload of iron through their Lohamarana and Shodhana, Anulomana, and Rasayana (antioxidant) properties. Most of them are Tridoshaghna and all are indicated in the Pandu Chikitsa. Therefore, they may help to decrease excessive destruction of the RBCs and thus help delay in blood transfusion.

Table 1.

Ingredients of Triphaladi Avaleha

The main aim of this study was to find a way to provide a better quality of life and to maintain the patient's health till bone marrow transplant was feasible.

Aims and Objectives

To assess the efficacy of Triphaladi Avaleha as an adjuvant therapy in the management of thalassemia, as a hepatosplenoprotector, a prolonger of RBC life span, and an iron chelator.

Materials and Methods

Prediagnosed patients attending the OPD of the Department of Kaumarbhritya, Institute for Post Graduate Teaching and Research in Ayurveda, Jamnagar, and patients from the thalassemia ward of GG Hospital, Jamnagar were selected for the present study.

Triphaladi Avaleha prepared in the pharmacy of Gujarat Ayurveda University was utilized for the present study.

Groups

Group A: The treated group was given Triphaladi Avaleha along with modern medical management

Group B: The control group received modern medical management only (i.e., blood transfusion and iron chelators)

Type of study: simple / randomized.

Posology

The dose of Avaleha in children is not clearly mentioned in the classic texts, so the dose was calculated according to Young's formula, taking the adult dose of Avaleha as 1 Pala (40 g). Thus, the dose according to the age was:

1 – 5 years : 3 – 12 g in three divided doses

6 –10 years : 13 – 18 g in three divided doses

11 – 15 years : 19 – 22 g in three divided doses

Anupana: Godugdha.

Duration of trial: Treatment period — Two months

Follow up — Two months

Inclusion criteria

Previously diagnosed patients between the age of 1-15 years of thalassemia were selected for the present study on the basis of clinical signs and symptoms

Exclusion criteria

Complicated cases (having HIV or HBV infection, hepatic failure, etc.) and those requiring blood transfusion at an interval of 15 days or less were excluded.

Criteria of assessment

A special proforma was made to collect data related to the pathogenesis of the disease, as well as the response to the given treatment and any complications. The efficacy of the therapy was assessed according to the scoring pattern given below.

Objective criteria: Routine hematological investigations were performed along with biochemical investigations for assessment of liver function and iron overload.

Subjective criteria: The subjective criteria for assessment included Panduta (pallor), Daurbalya (weakness), Balakshaya (chronic fatigue), Jwara (irregular fever), Aruchi (anorexia), Pleehavriddhi (splenomegaly), Yakritvriddhi (hepatomegaly), Vivarnata (complexion), Udara Shoola (abdominal pain), Atisra (loose motion), Pindikoudwesthana (muscle cramps), and Sandhi Shoola (joint pain).

Assessment of total effect of therapy

The assessment of progress was done after two months, that is, after completion of the course of treatment. An assessment scale was framed to assess the rate of improvement. At the end of treatment, the percentage of relief was calculated and classified under the following headings:

Maximum improvement: More than 75% improvement of the clinical signs and symptoms

Moderate improvement: 50 – 75% improvement of the above-mentioned clinical signs and symptoms

Mild Improvement: 25 – 50% improvement of the above- mentioned clinical signs and symptoms.

Observations and Results

In the present clinical study the patients were randomly separated into two groups. Out of 30 patients, 22 completed the course of treatment (thirteen in group A and nine in group B); eight patients dropped out of the study.

The largest proportion of patients (46.67%) were in the age group of 11 – 15 years, 60% were males, 83.33% were Hindus, 70.00% were literate, and 53.33% of the patients belonged to the middle class. In 80.80% of the patients the diagnosis had been made before the age of one year. Among the 30 patients, 3.33% of the patients had received blood transfusions up to 25 times, 13.33% patients had received transfusions 25 – 50 times, 30.00% of the patients 50–100 times, 36.67% of the patients 100 – 200 times, and 16.67% of the patients > 200 times. A history of consanguineous marriage was found in 56.67% cases. With regard to the order of birth, 53.34% were first-borns; 20.00% of the patients were second in the birth order, and 23.33% of the patients were third in the birth order. Amla Rasa Pradhanya was seen in 86.66% of the patients. Predominance of Guru and Sheeta Guna in the diet was found in 96.67% and 93.33% of the patients, respectively.

Vata-Pitta Doshika Prakriti was found in 66.67% of the patients. Most of the patients included in this study (86.67%) had Avara Sara, whereas, the remaining 13.33% patients had Madhyama Sara. Most of the patients (80.00%) were found to be with Avara Samhanana, while 20.00% patients had Madhyama Samhanana. Avara Satmya was seen in 80.000 % of the patients. Madhyama Satva was present in 63.63% and Avara Satva in 23.34%. Avara Abhyavaharanashakti was seen in 70.00% of the patients, while 42.10% patients had Madhyama Abhyavaharanashakti. Avara Vyayamashakti was seen in 26.67% of the patients, while 73.33% of the patients had Madhyama Vyayamashakti. Rasavaha and Raktavaha Sroto-Dushti was found in 100% of the patients, followed by Mansavaha Sroto-Dushti in 86.67%, Asthivaha Sroto-Dushti in 96.67%, and Sukravaha Sroto-Dushti in 20% of the patients [Table 2].

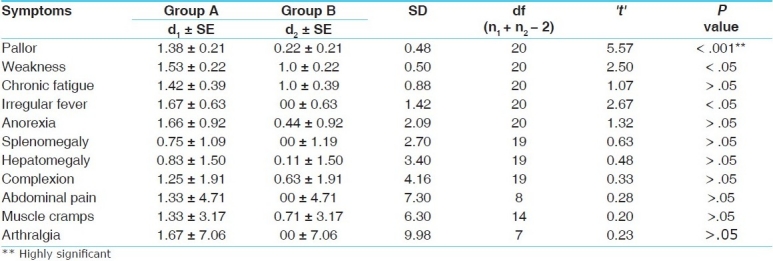

Table 2.

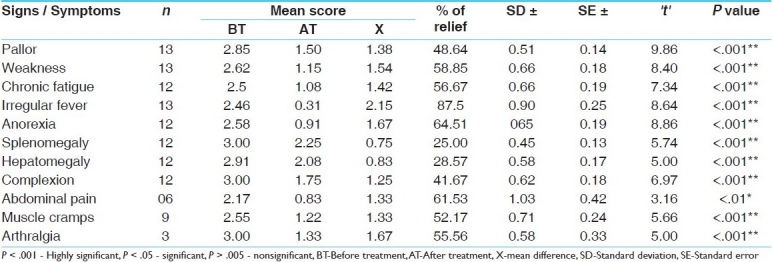

Effect of the therapy on the signs and symptoms in group A (treated with Triphaladi Avaleha plus blood transfusion)

With regard to the chief complaint, out of 30 patients, pallor, weakness, and chronic fatigue was found in 100% of the patients; irregular fever in 90%; splenomegaly and hepatomegaly in 86.67%; muscle cramps in 80%; dark complexion and anorexia in 76.67%; joint pain in 40%; and abdominal pain in 20% of the patients.

There was a significant (P < .01) relief of abdominal pain and highly significant (P < .001) relief in all the other cardinal features of thalassemia in patients receiving Triphaladi Avaleha [Table 2].

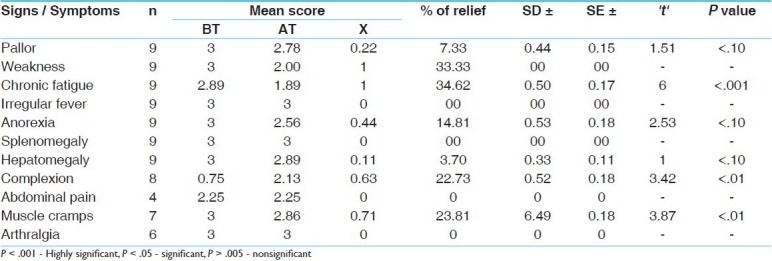

There was highly significant relief (P < .001) in chronic fatigue, significant relief (P < .01) in blackish complexion and muscle cramps. The effect of therapy in group B is shown in Table 3. The Tables 4–7 show the effect of therapy in group A and B on laboratory parameters and comparison of the effects.

Table 3.

Effect of therapy on signs and symptoms in group B (treated with deferiprone plus with blood transfusion)

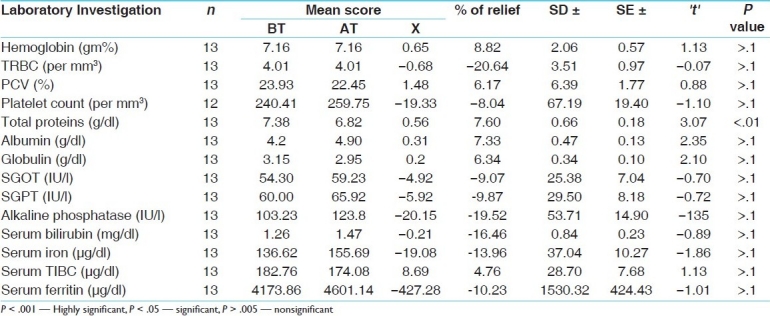

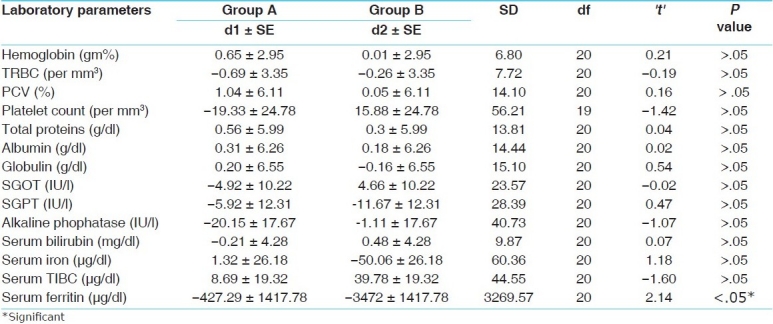

Table 4.

Effect of therapy on the laboratory parameters in group A

Table 7.

Comparison of the effect of the trial drug with that of the standard control on laboratory parameters

The changes in the laboratory parameters were not significant except in the case of total proteins, where the mean value before transfusion, of 6.82 g/dl, increased to 7.38 g/dl after transfusion, that is, there was 7.33% relief (P < .01) [Table 4].

The trial drug proved better than the standard control in pallor (P < .001; highly significant). In the other cardinal features there was no significant difference between the two groups [Table 6].

Table 6.

Comparison of the efficacy of group A with that of group B on the cardinal features of thalassemia major

The trial drug proved more effective that the standard control in lowering the serum ferritin level (P < .05); however, in the other laboratory parameters there was no significant difference between the two [Table 7].

Overall effect of therapy

After two months of treatment, in group A (treated group) one patient (7.69%) showed moderate improvement and 11 patients (84.61%) showed mild improvement, whereas in group B (control group) no change was observed in any patient.

Discussion

Thalassemia is the most common autosomal recessive genetic disorder affecting children worldwide. It has highly variable clinical expression (heterogeneity). Despite the heterogeneity, the thalassemias have in common a deficiency in the synthesis of one of the polypeptide chains. It is more prevalent in particular communities and used to be seen in particular geographic regions. However, migration of large numbers of people over time has led to changing demographics, and thus, one can now find patients of thalassemia all over the world. It severely jeopardizes the growth and development of the affected child. For Ayurveda it is a new clinical entity, and hence is termed as Anukta Vyadhi, which means ‘not told, unheard of.’[13] Although it is Anukta Vyadhi in Ayurveda its etiopathogenesis can be interpreted by the application of the excellent methodology given by Charaka.[14] Thus, the hemoglobin enclosed in the erythrocytes should be considered as Sthayi Rakta Dhatu. The enzyme system required for the synthesis heme moiety, which is responsible for imparting color to the hemoglobin should be taken as the Ranjaka Pitta. The enzyme system required globin chain synthesis; energy metabolism synthesis of glutathione should be taken as Raktagni. Although the various causes of mutation are mentioned in the Ayurvedic classics, the cause of mutation in the case of this disease appears to be a consequence of evolutionary protection against falciparum malaria. The genetic bases of various diseases were known to our ancient Acharyas, including their cause (Hetu) that is Upatapti[15] of Beeja, Beejabhaga, and Beejabhagavyava. They have described the genetic basis of various diseases like Arsha, Prameha, Kushtha, and so on. They have also described the possible cause of mutation in the form of Matru-Pitru Apachar, Daivya, Purvakrita Ashubha Karma, and Prakopa of Vatadi Dosha. The last one appears to be paramount rational. The role of the above-mentioned causative factors in engendering mutation till date is a matter of great inquiry. Whatever may be the nature and extent of Uptapti or Beeja Dosha, our ancient Acharyas focused on the resultant variability or the phenotype. They also used terms like Upahatava and Prajoptapa to describe the myriad clinical consequences of mutations. They also discussed the possible grave consequences in the form of Tridosha Prakopa Vikrut Avayva formation, which corresponds to the biochemical abnormalities or functional abnormalities and structural defects. The same is known to occur in thalassemia also. Modern medicine has various shortcomings in the management of this disease. The blood transfusion given to correct anemia leads to hemosiderosis and the consequent complications of organ damage, with death in the second or third decade due to cardiac hemosiderosis. According to Ayurvedic parlance thalassemia can be named as Kulaja Vikara / Anuvanshika Vikara / Beejadhustijanya Vikara. The concept of ‘Atulyagotriya Vivaha’ in Ayurveda can be helpful for the prevention of this disease. However, it should not be made mandatory in the light of modern diagnostic techniques available to test the carrier stage.

Most of the patients in our study were from the young and adolescent age groups. It has been observed in various studies that adolescents are generally less compliant than younger children in taking regular desferrioxamine and other iron chelation.[16] This fact was taken into consideration and counseling was given regarding the need for adequate iron chelation. Parents from the lower socioeconomic strata were more likely to have more than one child with thalassemia due to lack of awareness about the disease and failure to use antenatal screening techniques. As thalassemia is an autosomal recessive disorder, the practice of endogamy over a long period of time results in increased risk of this disease (as also other recessive disorders). This is the reason why this disease is more prevalent in certain communities located in specific geographical areas.

Thalassemia major, being a genetic disorder, is incurable. In such disorders improvement in the quality of life of the patient, minimizing the complications of the disease, as well as increasing the life span are to be given due emphasis, when planning clinical trials. The adverse effects with the existing modes of treatment of thalassemia are almost equal to the benefits that can be expected. The only curative therapy available for the management, that is, bone marrow transplant, is not affordable by the lower socioeconomic groups. On the other hand, a desirable outcome is attained only if the serum ferritin level is well controlled, below 2500 ng/dl, and if the liver damage is minimal. Human gene therapy for conditions like thalassemia are still in the primitive stage. Considering all these factors, the present study was planned as an experiment to find a new protocol for the management of thalassemia, which could minimize the complications without producing any ill effects.

While analyzing the efficacy of the trial drug (Triphaladi Avaleha) as compared with the standard protocol of management a significant reduction of serum ferritin levels was seen; this could be interpreted as a decrease in the iron overload. The majority of the symptoms of thalassemia are reported to be the result of iron overload in various tissues and organs. Some of the ingredients of Triphaladi Avaleha have potential iron chelating activity and would have contributed to the reduction in serum ferritin.

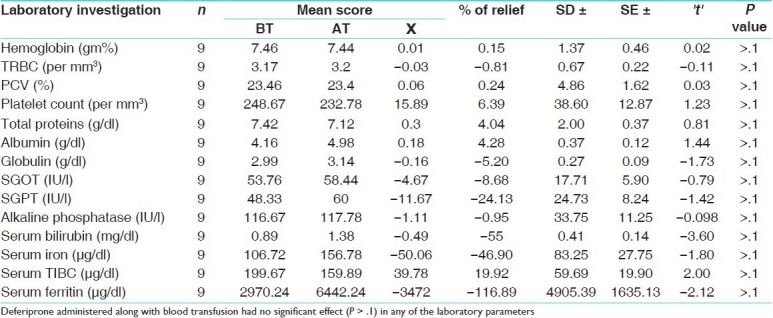

Tables 4 and 5 show that reduction in serum ferritin in both treated and control groups was not statistically significant. The various studies that have established the efficacy of modern chelators were of more than one-year duration with follow-up periods of up to three years. The sample size of this study was small and the duration of treatment was short. This might be the cause behind the nonsignificant differences between the two groups. Despite these shortcomings, the treated group showed better results than the control group. For this unpaired ‘t’ was utilized.

Table 5.

Effect of therapy on laboratory parameters in group B

Although the drug failed to prove better than the standard control in any of the other laboratory parameters, highly significant results were obtained in many of the subjective symptoms like pallor, weakness, chronic fatigue, irregular fever, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, anorexia, muscle cramps, and arthralgia. This could be attributed to the ingredients of the trial drug having Rasayana and Tridoshaghana properties. These Rasayana and Tridoshaghna properties possibly helped in the maintenance of the transfused Rakta Dhatu and all the other Dhatus. As there was no uniformity in the type of blood transfused and because of individual variations in the rate of decrease in hemoglobin, due to various causes like hypersplenism. The assessment of pallor was dependant on subjective parameters and it might be subject to error. Hence, we recommend that future studies assess the pretransfusion hemoglobin levels after ensuring the uniformity of the blood to be transfused irrespective of the blood transfusion interval.

Although it will be premature to make any concrete conclusion from the data of such a small number of patients, the improvement shown in the subjective parameters could be taken as signs of improvement in the quality of life of the patients. As the drugs used in the combination are free from any toxic effects, treatment with the same for a longer duration in large samples can be conducted for better assessment of this protocol.

Conclusion

In this study the effect of Triphaldi Avaleha was found to be significant (P < .01) in abdominal pain and highly significant (P < .001) in all the other cardinal features of thalassemia. Deferiprone administered along with blood transfusion had a highly significant (P < .001) effect in reducing chronic fatigue and a significant effect in reducing muscle cramps and blackish complexion. Treatment with Triphaldi Avaleha had no significant effect on the laboratory parameters, except in the case of total proteins (P < .01); in the control group all the laboratory parameters were unaffected. In the effect on the cardinal features of thalassemia major, we found that the trial drug was significantly (P < .001; highly significant) better than the standard control, in decreasing pallor, but the differences were not significant for the other features. The trial drug was better than the standard control in lowering the serum ferritin level (P < .05), whereas, it had no significant impact on any of the other laboratory parameters.

References

- 1.Braunwald, Fauci, Kasper, Hauser, Longo, Jameson . 15th ed. Mc Graw Hill Publication; 2001. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, International Edition; p. 673. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrman, Kliegman, Jenson . 17th ed. Saunders Publication; 2005. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics; p. 1632. [Google Scholar]

- 3.2nd ed. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2002. IAP Text Book of Pediatrics by A. Parthasarthy; p. 505. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghai OP, Pal P, Paul VK. 5th ed. Mehta Publication; 2003. Ghai Essential Paediatrics; p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- 5.2nd ed. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2002. IAP Text Book of Pediatrics by A. Parthasarthy; p. 505. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambekar SS, Phadke MA, Mokashi GD, Bankar MP, Khedkar VA, Venkat V, et al. Pattern of Hemoglobinopathies in Western Maharashtra. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:530–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sengupta M. Thalassemia among the tribal communities of India. Internet J Biolo Anthropo. 2008;1:2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghai OP, Pal P, Paul VK. 5th ed. Mehta Publication; 2003. Ghai Essential Paediatrics; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behrman, Kliegman, Jenson . 17th ed. Saunders Publication; 2005. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics; p. 1632. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braunwald, Fauci, Kasper, Hauser, Longo, Jameson . International Edition. 15th ed. Mc Graw Hill Publication; 2001. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine; p. 673. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee GR, Foerster J, Lukens J, Paraskevas F, Greer JP, Rodgers GM. 10th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publication; 1998. Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology; p. 1424. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee GR, Foerster J, Lukens J, Paraskevas F, Greer JP, Rodgers GM. 10th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publication; 1998. Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology; p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee GR, Foerster J, Lukens J, Paraskevas F, Greer JP, Rodgers GM. 10th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publication; 1998. Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology; p. 1424. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulkarni DA, Rasaratasamuccaya, editors. New Delhi: Meharchand Laxmandas publications; 1998. Lohashodhana Gana; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sir Monier Monier-Willims & other Scholars; ASanskrit-English Dictionary, Etymology & Philiology arranged With special refrence to cognate Indo-Europian language;searchable Digital Fascimile; The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International. 2002:31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadavaji T, editor. 6. Vol. 4. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrita Samnsthana; 2004. Charaka Samhita by Agnivesha, revised by Charaka and Dridbala, Commented by Chakrapanidatta; p. 248. reprint Vimana Sthana. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charaka Samhita, Sharira Sthana. 3(17):315. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cromer B, Tarnowski KJ. Non-compliance in adolescents: a review. J Pediatr Nurs. 1989;4:36–47. [Google Scholar]