Following the approval of OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Canada) for medical use, the media began to report the use of OxyContin as a street drug, representing the phenomenon as a social problem. Meanwhile, the pain medicine community has criticized the inaccurate and one-sided media coverage of the OxyContin problem. The authors of this study aimed to contribute to an understanding of both sides of this controversy by analyzing the coverage of OxyContin in newspapers and medical journals. The analyses revealed inconsistent messages about the drug from physicians in the news media and in medical journals, which has likely contributed to the drug’s perception as a social problem. The authors suggest ways to address the lack of medical consensus surrounding OxyContin. The results of this study may help resolve the concerns and conflicts surrounding this drug and other opioids.

Keywords: Media, Opioids, OxyContin, Public opinion, Social issues, Sociology

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

There are public concerns regarding OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Canada) and charges within the pain medicine community that media coverage of the drug has been biased.

OBJECTIVE:

To analyze and compare representations of OxyContin in medical journals and North American newspapers in an attempt to shed light on how each contributes to the ‘social problem’ associated with OxyContin.

METHODS:

Using searches of newspaper and medical literature databases, two samples were drawn: 924 stories published between 1995 and 2005 in 27 North American newspapers, and 197 articles published between 1995 and 2007 in 33 medical journals in the fields of addiction/substance abuse, pain/anesthesiology and general/internal medicine. The foci, themes, perspectives represented and evaluations of OxyContin presented in these texts were analyzed statistically.

RESULTS:

Newspaper coverage of OxyContin emphasized negative evaluations of the drug, focusing on abuse, addiction, crime and death rather than the use of OxyContin for the legitimate treatment of pain. Newspaper stories most often conveyed the perspectives of law enforcement and courts, and much less often represented the perspectives of physicians. However, analysis of physician perspectives represented in newspaper stories and in medical journals revealed a high degree of inconsistency, especially across the fields of pain medicine and addiction medicine.

CONCLUSION:

The prevalence of negative representations of OxyContin is often blamed on biased media coverage and an ignorant public. However, the proliferation of inconsistent messages regarding the drug from physicians plays a role in the drug’s persistent status as a social problem.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Le public s’inquiète au sujet de l’OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Canada). Dans le domaine de la médecine de la douleur, on croit que la couverture médiatique du médicament est biaisée.

OBJECTIF :

Analyser et comparer les représentations de l’OxyContin dans les revues médicales et les journaux d’Amérique du Nord afin de jeter la lumière sur la manière dont ces médias contribuent à la croyance selon laquelle l’OxyContin s’associe à un « problème social ».

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Au moyen de recherches dans les bases de données des journaux et des publications médicales, les auteurs ont extrait deux échantillons : 924 articles publiés entre 1995 et 2005 dans 27 journaux d’Amérique du Nord, et 197 articles publiés entre 1995 et 2007 dans 33 revues médicales dans les domaines de la toxicomanie, de la consommation abusive d’alcool et de drogues, de la douleur et de l’anesthésiologie ainsi que de la médecine générale et de la médecine interne. Ils ont procédé à une analyse statistique des éléments centraux, des thèmes, des perspectives et des évaluations de l’OxyContin présentées dans ces textes.

RÉSULTATS :

La couverture journalistique de l’OxyContin faisait ressortir les évaluations négatives du médicament, s’attardant sur la consommation abusive, la toxicomanie, les délits et les décès plutôt que sur l’utilisation de l’OxyContin pour le traitement légitime de la douleur. Les journaux traitaient surtout des perspectives de la répression criminelle et des tribunaux et moins de celles des médecins. Cependant, l’analyse des points de vue des médecins représentés dans les articles de journaux et les revues médicales a révélé un taux élevé de contradictions, notamment dans les domaines de la médecine de la douleur et des troubles de toxicomanie.

CONCLUSION :

La prévalence des représentations négatives de l’OxyContin est souvent imputée à une couverture médiatique tendancieuse et à un public ignorant. Toutefois, la prolifération de messages contradictoires au sujet du médicament de la part des médecins contribue au statut persistant du médicament à titre de problème social.

The story is a familiar one to readers of Pain Research & Management. OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Canada), a controlled-release formulation of the opiate agonist oxycodone, was approved for medical use in the United States (US) in 1995, and then in Canada in 1996. The drug was considered to be a breakthrough, both for its ability to provide sustained relief from pain and because both its manufacturer and the US Food and Drug Administration expected that its extended-release formula would make it less prone to abuse than other opioids (1). Within five years, the popular and medical presses began to report the use of OxyContin as a street drug, particularly in rural communities in the eastern US, earning it the nickname ‘hillbilly heroin’. Since then, OxyContin has been represented regularly as a devastating social problem in Atlantic Canada and many other economically disadvantaged, rural regions of North America.

However, media representations of OxyContin as primarily a drug of abuse have not gone unchallenged. For instance, the Canadian Pain Society (CPS) issued a press release in August 2004 (2) criticizing the inaccurate and one-sided media coverage of the OxyContin problem:

Most of these stories have failed to mention that the vast majority of people, who use these medications properly, greatly benefit from reduced pain. As a result of this recent media coverage, all Canadians who take opioid analgesics to treat chronic pain have been stigmatized and made to feel like they might be doing something wrong…Patients with moderate to severe pain from injuries, cancer or other medical conditions should not be denied medications that can provide needed relief, nor should they feel afraid or ashamed to take the medication they need because these legitimate products have become stigmatized as ‘drugs of abuse’.

Another CPS news release about the biases in media reporting, specifically by the CTV program W5, followed. Indeed, since the advent of the crisis, we have witnessed a flurry of consensus documents, media interviews and best practice guidelines from pain societies across North America. However, efforts to reframe the use of opioids for pain as an appropriate therapeutic option in properly screened patients seem to have had limited impact because recent Canadian headlines pertaining to the drug have expressed familiar themes: “Study links OxyContin to increase in deaths” (Toronto Star, December 7, 2009); “Newborns going through withdrawal from moms’ painkiller abuse” (Vancouver Sun, January 18, 2010); “Oxycontin blamed for town’s home-invasion trend” (Toronto Sun, January 29, 2010); “Man sold Oxy to supply his own habit” (Sudbury Star, January 26, 2010).

The present article reports the first phase of a four-year study of the problematization of OxyContin, and the responses of pain and addiction experts and pain activists to that problematization. The study was funded by the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation; no funding was provided by the pharmaceutical industry. We present quantitative data regarding North American newspaper representations of OxyContin from 1995 to 2005 – a period that began with the introduction of this much-heralded drug and ended with several waves of public concern about its abuse. The story is ongoing, but these data paint a picture of the formation and initial responses to the crisis. Our data demonstrate that the concerns of the CPS, in 2004, regarding one-sided media coverage were well founded. However, we questioned why this media coverage was so one sided. To that end, we also present quantitative data regarding the coverage of OxyContin by medical journals from 1995 to 2007. These data suggest that the broader medical community was sending highly variable, inconsistent messages to the public and, consequently, to the news media in its representations of OxyContin. This lack of consistency may have fuelled the media circus surrounding the drug, and contributed to the fear and uncertainty surrounding its use and the use of other opioids in the treatment of pain – a legacy that the pain medicine community is still dealing with today.

Other authors have reported on research that examines the extent to which OxyContin is abused or associated with criminal activity (1,3–5). One recent article (6) examined the effects of newspaper representations of drugs such as OxyContin on opioid-related mortality and abuse, arguing through a quantitative analysis that media coverage publicizing their psychoactive effects and abuse may popularize and increase their illicit use. Our concern in the present study was not to examine the effects of OxyContin on society or human health, nor to analyze the damage to human health that media representations of the drugs may cause. Instead, our goal was to analyze competing representations of OxyContin as both a deadly street drug and a legitimate medication for the treatment of pain. In doing so, we contribute to a well-established body of literature on the construction of social problems, drug scares and the media’s involvement in both (7–13).

In sociology, the term ‘social problem’ is defined as “an alleged situation that is incompatible with the values of a significant number of people who agree that action is needed to alter the situation” (14). Each part of this definition is important. First, a social problem must be alleged (ie, said to exist, talked about); for a phenomenon to be defined as a social problem, it must be discussed as such in a social arena. Often, for example, the public arenas of the news media are used to make the case that a phenomenon constitutes a social problem. Second, for this phenomenon to be regarded as a social problem, it must be incompatible with some peoples’ values; a moral judgement must be attached to it. A social problem is something that is defined as somehow wrong, at least by some people (although others may disagree). Third, the phenomenon must be identified as a problem by a significant number of people. The actual number is quite arbitrary, but the people themselves may not be because “some people are more significant than others” (14). Those most likely to have a phenomenon branded a problem are groups of people who are well organized (for example, social movement organizations), people who are in positions of leadership, or people who are economically, socially and/or politically powerful. Fourth, and finally, social problems are phenomena about which, it is argued, something must be done. Definitions of social problems as things that are wrong go hand-in-hand with calls for remedial action to make things right.

The point of this sociological definition is to call attention to the social process whereby a phenomenon comes to be considered a social problem. For social problems scholars – at least those working from the constructionist perspective – social problems do not exist ‘in nature’; they must be ‘constructed’ or made (ie, defined and designated as problems by social actors). To be clear, this does not mean that a social problem is not really a problem; by definition, once something has come to be represented as a social problem by sufficiently important social actors, others are often forced to respond to it as such. Generally, social problems scholars are less concerned with arguing that a phenomenon is or is not a problem, than in studying how the phenomenon came to be regarded as a problem, how the argument that it was a problem was made, by whom it was made, and why (see reference 15 for an example). Their interest is primarily in the problematization process. By examining how we, as a society, define social problems, social problems scholars draw attention to our society’s norms, politics, sources of power and resistance to power, practices of social control, and the consequences – intended and unintended, positive and negative – that problematization may have for individuals and for society. Our broader concern is to establish the strategies by which OxyContin has been problematized, but also the strategies used by groups concerned with maintaining its legitimate use to challenge or question OxyContin’s problematization. By examining these strategies, we hope to contribute to an understanding of both sides of this controversy, which may contribute to the resolution of concerns and conflicts surrounding this drug and other opioids – goals that will be shared by many readers of Pain Research & Management.

METHODS

Newspaper coverage

First, the coverage of OxyContin was analyzed, from its approval in 1995 to the end of 2005, in 27 newspapers (Table 1). Six were Canadian and 21 were from the US.

TABLE 1.

American and Canadian newspapers analyzed

| Canadian newspapers | American newspapers |

|---|---|

| West | West |

| The Vancouver Sun | The Denver Post |

| The San Francisco Chronicle | |

| The Seattle Times | |

| The Houston Chronicle | |

| Midwest | Midwest |

| The Winnipeg Free Press | The Chicago Sun-Times |

| The Cleveland Plain Dealer | |

| The Columbus Dispatch | |

| The Omaha World Herald | |

| The St Louis Post-Dispatch | |

| The Minnesota Star Tribune | |

| Central | Northeast |

| The Globe and Mail (Toronto) | The Boston Globe |

| The Montreal Gazette | The Boston Herald |

| The Buffalo News | |

| The New York Daily News | |

| The New York Times | |

| The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette | |

| The Wall Street Journal | |

| East Coast | Southeast |

| The Halifax Chronicle-Herald | The Atlanta Journal |

| The Cape Breton Post | The Tampa Tribune |

| The Washington Post | |

| National | |

| USA Today |

The choice of newspapers was governed by several factors. First, because articles were retrieved through news media databases (Factiva, LexisNexis and Virtual News), the choice of newspapers was limited to those that were indexed in these databases during the entire time period being studied (January 1, 1995, to December 31, 2005). This eliminated many newspapers that otherwise would have been good choices, but was necessary to ensure consistent sampling. Of the newspapers that were available during the entire period, those that would ensure geographical coverage across major regions of the US and Canada were chosen. Newspapers chosen either had a significant circulation or were the main newspapers for their regions; for example, the latter characteristic was important in our selection of The Cape Breton Post, a newspaper with a relatively small circulation but that serves an area where OxyContin abuse is widely considered to be a significant problem.

Paper-by-paper searches were conducted in the databases mentioned for all articles containing OxyContin in their title, lead paragraph or key words. The result was a total sample of 924 stories, and all 27 newspapers were represented in the sample. Each story was coded and entered into SPSS version 15.0 (IBM Corporation, USA), and all entries were reviewed to check for errors and address discrepancies. Each article was coded using several fields, covering date of publication, newspaper source, title of the article and contextual details about the article. Contextual details included the location of the article in the newspaper (front page, middle of the paper, etc), length of the article (number of words) and the type of article (eg, editorial, news brief, letter to the editor or feature). Also, the themes and problems represented in the article were recorded. Finally, the perspectives of groups and individuals (doctors, law enforcement, pharmaceutical industry, etc) quoted or cited in the article were captured.

Medical journal coverage

Second, the coverage of OxyContin in medical journal articles was analyzed. A list of important medical journals in the categories of addictions and substance abuse, general and internal medicine, and pain and anesthesiology was generated using a combination of searches in Journal Citation Reports (JCR) 2005, the authors’ own previous research in the fields of pain and addictions medicine, and recommendations by Canadian experts in both fields. The same number of journals in each category was chosen to ensure a similar breadth of coverage in each field. The final list included 17 journals in addictions and substance abuse disciplines, 17 journals in general and internal medicine with a JCR impact factor of 2 or higher, and 17 journals in pain and anesthesiology (Table 2); all of these journals published articles in English.

TABLE 2.

Medical journals analyzed

|

Addictions and substance abuse |

| Addictive Behaviors |

| Addiction |

| Addiction Biology |

| The American Journal on Addictions* |

| The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse |

| Drug and Alcohol Dependence* |

| Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy |

| Drug and Alcohol Review |

| European Addiction Research |

| Harm Reduction Journal |

| International Journal of the Addictions/continues as Substance Use & Misuse* |

| Journal of Addiction Medicine |

| Journal of Addictive Diseases* |

| Journal of Drug Issues* |

| Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs* |

| Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment* |

| Substance Abuse |

|

General and internal medicine |

| American Journal of Medicine |

| American Journal of Preventive Medicine* |

| Annals of Internal Medicine* |

| Annals of Medicine |

| Annual Review of Medicine |

| Archives of Internal Medicine |

| British Medical Journal |

| Canadian Medical Association Journal* |

| Current Medical Research and Opinion* |

| Journal of General Internal Medicine* |

| Journal of Internal Medicine* |

| JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association* |

| Lancet |

| Mayo Clinic Proceedings* |

| Medicine |

| New England Journal of Medicine* |

| PLoS Medicine |

|

Anesthesiology and pain |

| Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica* |

| Anaesthesia* |

| Anesthesia & Analgesia* |

| Anesthesiology* |

| British Journal of Anaesthesia* |

| Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia* |

| The Clinical Journal of Pain* |

| European Journal of Anaesthesiology* |

| European Journal of Pain* |

| Journal of Clinical Anesthesia* |

| Pain Forum/continues as Journal of Pain* |

| Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy* |

| Journal of Pain and Symptom Management* |

| Pain* |

| Pain Medicine* |

| Pain Research & Management* |

| Regional Anesthesia/continues as Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine* |

One or more OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Canada)-related article(s) were published in the journal

Searches were conducted in two databases (Web of Science and PubMed) for articles published in English in the journals listed in Table 2, with OxyContin or oxycodone in the subject or key word field, published between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2007. Note that the period chosen for the journal search was two years longer than the one chosen for the newspaper search. The goal was to compare newspaper coverage and discussions of the drug in medical journals following the rise of concerns regarding OxyContin; if the sampling period had been the same, many medical journal articles written in response to social concerns regarding OxyContin would not have been published yet. The longer sampling frame allowed us to take into account the longer time it takes for academic research to be conducted and published when compared with newspaper stories – a lag that was estimated to be two years.

Several journals of interest began publishing after 1995 but were too important to exclude from the sample. Other journals were published during the entire period but were not indexed in PubMed or Web of Science at all, or were only published during a part of the period. To cover these gaps, searches on the journals’ or publishers’ websites were conducted by the project coordinator. Thus, all of the journals indicated were searched for their entire run of publication between 1995 and 2007.

One important limitation of any study similar to the present one is the quality and consistency of the indexing in a database (ie, the association of articles with key words or subjects). Variations and errors occur in many ways. First, different databases index differently, so that a journal’s own website may assign the subject or key word ‘oxycodone’ to articles more or less freely than PubMed. Second, individuals who work on a given database may vary in their indexing approach – in their tendency to assign a given key word to an article, for instance. Third, even the same individual may not be consistent in the way he or she indexes articles. Fourth, articles may be indexed incorrectly; in the present study, a few articles that did not mention oxycodone were assigned a major subject heading of oxycodone. Each article that did appear in the searches was reviewed to determine whether OxyContin or oxycodone were discussed and coded for relevance. The final sample of 197 articles included only those in which OxyContin was the primary or an important secondary focus. This represented 33 journals (seven in addictions and substance abuse disciplines; nine in general and internal medicine; and 17 in pain and anesthesiology) (see journals in Table 2 marked with an asterisk). Information coded and analyzed in SPSS included the year the article was published, journal type (ie, addictions and substance abuse; pain and anesthesiology; general and internal medicine), article type (eg, letter to the editor or research report), article foci, and whether a problem or crisis involving OxyContin was identified.

RESULTS

Newspaper coverage

First, the distribution of the 924 newspaper articles reporting OxyContin-related stories between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2005, is presented. No newspaper articles discussed OxyContin in the North American media until March 11, 2000, when a story appeared in The Columbus Dispatch titled, “Officials hope doctor’s arrest will stem flow of illegal drugs; Scioto County man charged.” While only four articles appeared in 2000, reporting on OxyContin took off in 2001 with 252 stories, followed by 116 stories in 2002, 146 in 2003, 231 in 2004 and 175 in 2005. The initial peak in coverage in 2001 occurred virtually entirely in the US print media (99% of stories); in Canada, the peak occurred in 2004 (43% of stories covered that year). More than 90% of all OxyContin stories published in Canada originated in two Nova Scotia daily papers (The Halifax Chronicle Herald and The Cape Breton Post). The majority of OxyContin coverage in US print media emerged from the east coast and originated in three dailies (The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and The Boston Herald) with only limited national coverage. This suggests that, at least during this period, OxyContin abuse was not seen as a great problem in all areas of North America. OxyContin stories tended to have feature coverage, with just over one-half of all OxyContin stories appearing either on the front page of the newspaper, in the main section of the newspaper or on the front page of another section of the newspaper. Slightly fewer than 50% of stories were in-depth feature articles, while 41% were news briefs and only 3% were editorials. The average word count was 443. There were no obvious time trends in the placement and type of articles.

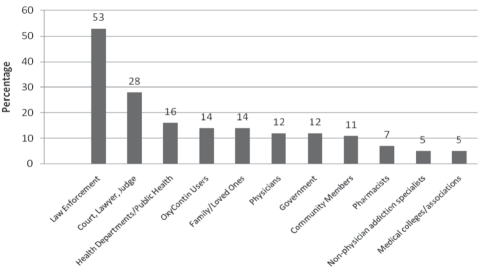

Beyond the general trends in reporting, the present study examined the nature of OxyContin reporting with a specific focus on whose opinions were being represented, the dominant themes in reporting and the types of problems/issues identified in OxyContin stories. First, the present study discussed whose perspectives were represented (that is, who was directly quoted or cited/paraphrased) in news stories addressing OxyContin. Thirteen nonmutually exclusive perspectives were identified, along with an open-ended category; more than one perspective could be represented in a single story. Figure 1 presents the most commonly represented perspectives.

Figure 1).

Perspectives represented in newspaper articles pertaining to OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Canada)

The perspectives of law enforcement officials/police were most commonly represented (53%) in OxyContin news stories, followed by court officials such as judges and lawyers (28%). Much less commonly represented were the perspectives of health departments and public health agencies (16%), users of OxyContin or their family members/loved ones (both at 14%), and physicians or government representatives (both at 12%).

In the 111 articles in which individual physicians’ perspectives were represented, some types of physicians were represented more often than others. The perspectives of pain specialists were most commonly represented (46% cited one or more physicians described as pain specialists or anesthesiologists), followed by addiction medicine/substance abuse specialists (16%), palliative care specialists (10%), psychiatrists (8%) and emergency medicine physicians (6%). Other types of specialists were cited in less than 5% of the 111 articles (for example, only one article cited a physician identified as a gastroenterologist). Thirty-one per cent of articles cited physicians of an unspecified type (they were identified simply as a physician).

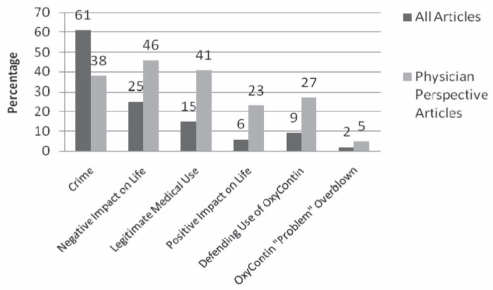

Second, the present study’s analysis of the themes covered in the stories is presented. Twelve broad, nonmutually exclusive themes and one open-ended category to describe the nature of the news story were identified. Figure 2 outlines the prevalence of themes presented in all articles and in physician-perspective articles; the patterns were quite different.

Figure 2).

Themes identified in newspaper articles pertaining to OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Canada)

By far, the dominant theme in the entire sample was crime. Articles in which physicians’ perspectives were included tended to focus much less on crime and more on the legitimate use of the drug to treat pain and the drug’s effects, both positive and negative, on people’s lives.

Third, the OxyContin stories were examined to determine what problems, if any, they identified. As noted above, most stories were framed around some sort of problem associated with OxyContin. Based on an initial review of the articles, 20 potential problems were identified; each story could address more than one problem. The most common problems identified in OxyContin stories were crime (64%) and addiction/misuse (63%), followed by OxyContin abuse as a cause of death (28%). Only 10% of articles addressed adverse effects on the treatment of pain and pain patients; these included under-prescribing and a lack of appropriate treatment for pain patients, and stigmatization of legitimate OxyContin users. Only 5% of OxyContin stories did not identify a problem. In articles that included physicians’ perspectives, the top problems associated with OxyContin were, again, addiction/misuse, crime and death; however, the numbers were quite different: 89% of this subsample discussed addiction/misuse, 55% crime and 47% death due to OxyContin. Physician perspective articles demonstrated more concern for adverse effects on the treatment of pain and pain patients (30%), doctors’ over-prescribing of the drug (29%), and the persecution of physicians who prescribe the drug (13%). As occurred in the sample overall, only 5% of stories that included physicians’ perspectives identified no problems. Thus, stories that included physician perspectives were somewhat less likely to discuss crime as a problem associated with the drug and, not surprisingly, were more likely to focus on the negative consequences that concern health care providers and their patients: addiction, death, over-prescribing, under-prescribing, patient access to treatment and professional problems.

Fourth, the articles’ suggested responses to problems associated with OxyContin were explored. In the sample overall, the most common suggested response to the OxyContin problem was increased education efforts, followed by increased law enforcement, and increased rehabilitation and treatment efforts. In 52% of stories, no action was called for. Stories that included physicians’ perspectives were more likely to recommend a specific action to address the OxyContin problem; only 30% called for no action, and the top three suggested remedies for the OxyContin problem were increased education (30%), increased rehabilitation and treatment efforts (20%), and the introduction of prescription monitoring programs (PMPs) (17%).

Finally, the present study reflected on the overall tenor of each article’s evaluation of OxyContin. As might be expected given the evidence provided above, 40% of all stories evaluated OxyContin negatively, while only 5% evaluated OxyContin positively. The remaining stories were either ambivalent (14%) in their evaluation of OxyContin or the story did not offer an evaluation (39%), often because the nature of the story prohibited it (for example, OxyContin was not a major focus, or the piece was a short news brief). In articles in which physicians’ perspectives were included, 41% offered a negative evaluation, 10% a positive evaluation, and 38% an ambivalent evaluation, while only 11% offered no evaluation at all. Thus, the inclusion of physicians’ perspectives substantially increased the likelihood that an evaluation of the drug would be offered in a story, and that the story would offer a positive or, more commonly, an ambivalent view of OxyContin.

Medical journal coverage

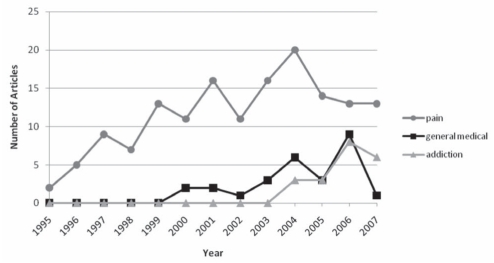

Following the analysis of newspaper stories and the role physician perspectives play in such stories, the present study analyzed the representation of OxyContin in physician-dominated forums (ie, medical journals). While the coverage of OxyContin in the newspaper article sample was highly erratic from year to year, the medical journals showed an overall pattern of increase in the number of articles discussing OxyContin from 1995 onward, although there were peaks in 2004 and 2006, and troughs in 1998, 2002, 2005 and 2007.

As Figure 3 illustrates, the different types of journals varied dramatically in their coverage of OxyContin. Pain and anesthesiology journals, which accounted for the majority of articles (76% of the sample), addressed OxyContin as a topic early on, showing a generally steady increase in the number of articles per year since 1995. General and internal medicine articles addressing OxyContin, which accounted for 14% of the sample, were not published until 1999, after which there was a slight increase yearly; from 2002 onward, however, there was a sharp peak/trough pattern. Interestingly, considering the prominence of the theme of addiction in newspaper stories about the drug, addictions and substance abuse journals accounted for the fewest articles (10% of the sample), and were the last to discuss OxyContin, with no articles addressing the drug appearing before 2004.

Figure 3).

Article distribution according to journal type

Expanding the timeframe by two years enabled the considerable increase in attention given to OxyContin in the general/internal and addictions journals in 2006 to be seen, compared with the peak reached two years earlier by the pain and anesthesiology journals. That is, the general/internal and addictions journals took some time to catch up with the newspaper coverage, suggesting that media coverage may have had more of an ‘agenda-setting’ effect in these fields than in pain medicine. In fact, pain medicine journals began acknowledging the potential problems of addiction and diversion/abuse in 1996 – four years before newspapers and general medicine journals, and eight years before addiction journals began to report these problems (in 2000 and 2004, respectively). The particular sensitivity of pain medicine to this issue is apparently recognized in the newspaper sample as well, because pain medicine specialists were consulted in articles addressing OxyContin much more often than other types of physicians, including addiction specialists. Nevertheless, in the newspaper sample, problems of crime, diversion, drug misuse, abuse and addiction were more commonly discussed than the problem of pain. In other words, although OxyContin was primarily represented as an issue for pain medicine in medical journals, in newspapers, it was presented as primarily an addiction or crime issue. This, again, supports the present study’s finding that medical perspectives on the drug have less impact in the news media than other perspectives (notably, those of police and law enforcement agencies, and court officials).

As might be expected, the medical journal sample placed much more emphasis on original research (68%) or secondary research (ie, literature reviews or meta-analyses) (19%) than on expert commentary (3%), editorials (1.5%), correspondence, ie, letters to the editor (2%) or other materials (7%). Article content also reflected what might be expected from medical journals, and may also reflect the fact that nearly three-quarters of the sample was derived from pain and anesthesiology journals: more articles discussed clinical issues and the basic science of the drug, rather than social, legal or policy concerns. In terms of the overall sample of articles (n=197), clinical drug trials regarding or involving OxyContin or oxycodone were a focus in 49% of the articles, pharmacology in 20%, use patterns and epidemiology of the drug in 17%, social/economic concerns regarding the drug in 15%, clinical guidelines/consensus statements in 9%, legal or policy issues in 9%, crime in 6%, and physician or pharmacist prescribing behaviour in 5%.

Different types of journals tended to emphasize different issues. Pain and anesthesiology journals focused mainly on the scientific aspects of the drug, with the top foci being clinical drug trials (47%) and pharmacology (19%). Surveillance was a focus in 9% of pain journal articles, clinical guidelines/consensus statements in 7% of articles, social/economic concerns and legal/policy issues in 6% of articles, and prescribing behaviour in 3% of articles, with crime being the least common focus (2%). Clinical trials also comprised the top focus for the general and internal medical category, but markedly less so (28%), followed by social/economic issues (20%) and clinical practice guidelines/consensus statements (13%), surveillance (10%), and pharmacology, crime and legal/policy issues (each at 8%), demonstrating a more varied approach to addressing issues surrounding OxyContin than pain/anesthesiology journals. Finally, the main focus in the addictions and substance abuse journal category was surveillance (38%), followed by social/economic concerns (20%), legal/policy issues and crime issues (each at 11%). Scientific aspects of the drug were addressed far less frequently; clinical trials and pharmacology each comprised only 3% of the foci within this category, and the least common focus in this category was prescribing behaviour (1%). Clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements were completely absent from the sample of addictions journal articles, in contrast to the other two categories that addressed the issue. Thus, there was little overall consistency among the three journal types.

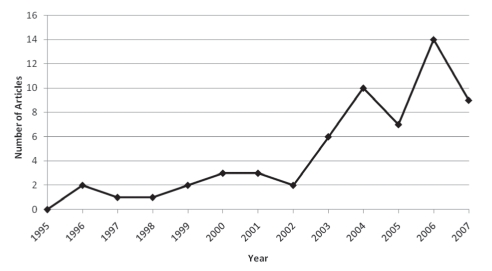

While medical journals tended to focus on the science or clinical use of the drug, 30% of the articles specifically acknowledged a perceived crisis or problems associated with OxyContin. A perceived problem associated with the drug was first noted in 1996, but acknowledgment of the perceived problem increased markedly after 2002 (Figure 4).

Figure 4).

Medical journal articles identifying an OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Canada) problem

The vast majority of addictions journal articles acknowledged a crisis (95%), in contrast to both the pain/anesthesiology and general/internal medicine journals, which only acknowledged a crisis in 20% and 39% of articles, respectively. In this respect, the addiction journals most closely mirrored the newspaper sample; both were very likely to present OxyContin as a problem drug. Given the relatively few newspaper articles in which addiction medicine specialists were interviewed, it would be a stretch to suggest that the news media derived their evaluation of the drug from addiction specialists; in fact, addiction journals only identified a crisis after one was identified in the news media. Thus, it seems more likely that media reports influenced addiction journal attention to the issue rather than vice versa.

Moreover, newspaper stories that contained medical perspectives also contained contradictions. Some quoted physicians focused on the adverse effects of the drug, while others advocated its use in appropriate populations, and decried the stigmatization and persecution of users and prescribers. Articles that cited addiction medicine specialists were much more likely to present an overall negative evaluation of OxyContin; in fact, addiction medicine specialists were not cited in a single story that evaluated OxyContin positively. On the other hand, newspaper stories that cited pain specialists were more likely to portray OxyContin in a positive or ambivalent way, and less likely to portray OxyContin negatively. Whether the physicians who were interviewed influenced the slant of articles or particular types of physicians were sought out by journalists already planning to write articles with particular slants is not clear. What is clear is that the types of physicians who are most intimately involved with OxyContin – pain specialists and addictions specialists – were associated in the print media with very different views of the drug.

CONCLUSIONS

The lack of consistency across medical representations of OxyContin – both in the newspapers and in medical journals, where almost all addiction articles represented OxyContin as a problem drug while only a minority of pain medicine articles did so – flies in the face of what the public has been told to expect from medical science. Lewenstein (16) noted that journalists tend to represent science as a “coherent body of knowledge”, rather than a field of conflict and siloization in which consensus across fields of study and even among specialists within a small field is difficult to achieve. By the time it reaches the public, ‘popular science’ – science presented for public consumption – tends to erase and ignore the controversies and complexities that one sees in, for example, ‘journal science’, where scientific findings are first presented tentatively and debated (17). Thus, when the public hears from a medical expert, they are taught to expect consistent messages that reflect a scientific consensus, regardless of whether such a consensus really exists. The public is not hearing about a medical consensus on OxyContin from the news media.

However, the news media is not the public’s only source of information regarding OxyContin, especially since the introduction of the Internet. The general public now has much greater access to journal science and, consequently, a potentially greater awareness of the playing-out of scientific controversies than in the past. In medical journals, there is no consensus regarding OxyContin either: almost all addiction articles represent OxyContin as a problem drug and only a minority of pain medicine articles do so. The public’s growing awareness of controversies within science means that the credibility of a claim cannot be promoted based solely on the presumption that all scientists agree, so the rest of us should agree with them; in fact, most of the time, they manifestly do not all agree. Educating the ‘ignorant public’ to agree with a given group based on their scientific credentials, when other well-qualified scientists openly disagree with that first group of scientists, seems to be a faulty strategy for increasing public faith in and cooperation with a scientific group’s claims. The promotion of the myth of scientific consensus despite readily available evidence to the contrary may only further undermine the credibility of those who claim such a consensus exists. Compared with the conflicting viewpoints of physicians presented in both the medical journals and the newspapers, the apparent consistency of messages coming from police and court officials regarding OxyContin is striking. This no doubt explains, to some extent, the effect that these sources have had on media representations of, public opinion regarding and state agencies’ responses to the abuse of OxyContin.

One common way of addressing the lack of medical consensus surrounding OxyContin, or any issue, is to publish consensus statements or clinical guidelines. Some quick searches on ‘Google’ and the US National Guidelines Clearinghouse for clinical guidelines and consensus statements regarding the use of opioids for pain generated 12 different documents – some produced by pain medicine societies, some by other medical groups, and many by particular state or health care administration agencies (18–30). This does not even include the many pain management guidelines issued for specific conditions that these searches yielded. The very creation of a National Guidelines Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov) by the National Institutes of Health suggests that the proliferation of usually conflicting guidelines by expert bodies, rather than creating clear directions and resolving conflict for health care providers, may be generating further confusion and disagreement regarding what counts as an expert opinion on appropriate clinical practice. The confusion generated by conflicting expert opinions has effects not only in the clinic, but in the larger society – and in the courtroom. Indeed, such conflicts, and not just public ignorance or media biases, contribute to the persistent status of OxyContin as a social problem. The publication of more guidelines for the use of opioids for pain management requires all physicians to be completely up to date on guideline publications and to know which guideline is preferred by whom at the present time. It remains to be seen whether the recent publication of the “Canadian Guideline for Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain” (31), which incorporates input from a wide medical constituency, will effectively address the problem of conflicting guidelines – at least in Canada.

Another, perhaps better, strategy might be to work toward an actual consensus across and within medical specialties and a consistent representation of that consensus in venues outside of scientific circles. However, this requires the breaking down of traditional boundaries among and between medical specialties, academic disciplines, health care professions and professional associations. Many prominent figures in North American pain medicine have begun to do this by collaborating with experts and professional associations in other fields (notably, addictions), and by developing networks that provide opportunities for family practitioners to consult pain and opioid specialists. Such initiatives are bound to create more synergy within the biomedical establishment and, potentially, help to resolve this social problem – one generated not merely by media frenzy or public ‘ignorance’, but also significantly by differences of opinion within medicine.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a project grant from the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation. A visiting scholar grant from the Brocher Foundation (Hermance, Switzerland) assisted the first author during the writing of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Muñoz A. Trends in abuse of OxyContin® and other opioid analgesics in the United States: 2002–2004. J Pain. 2005;6:662–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Pain Society Media Coverage of OxyContin is One-Sided: A statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Press Release. Aug 19, 2004. < www.canadianpainsociety.ca/formulaires/PressReleasesCPSAugust202004.pdf> (Accessed on April 11, 2005).

- 3.Adlaf EM, Paglia-Boak A, Brands B. Use of OxyContin by adolescent students. CMAJ. 2006;174:1303. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1060037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inciardi JA, Cicero TJ. Black beauties, gorilla pills, footballs, and hillbilly heroin: Some reflections on prescription drug abuse and diversion research over the past 40 years. J Drug Issues. 2009;39:101–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tunnell KD. The OxyContin epidemic and crime panic in rural Kentucky. Contemp Drug Probl. 2005;32:225–58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dasgupta N, Mandl KD, Brownstein JS. Breaking the news or fueling the epidemic? Temporal association between news media report volume and opioid-related mortality. PLoS One. 2009;4:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altheide DL. Creating Fear: News and the Construction of Crisis. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Best J. Random Violence: How We Talk About New Crimes and New Victims. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowney KS. Claimsmaking, culture, and the media in the social construction process. In: Holstein JA, Gubrium JF, editors. Handbook of Constructionist Research. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 331–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller G, Holstein JA, editors. Constructionist Controversies: Issues in Social Problems Theory. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orcutt JD, Turner JB. Shocking numbers and graphic accounts: Quantified images of drug problems in the print media. Soc Probl. 1993;40:190–206. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinarman C. The social construction of drug scares. In: Adler PA, Adler P, editors. Constructions of Deviance. Belmont: Wadsworth; 1994. pp. 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spector M, Kitsuse JI. Constructing Social Problems. Hawthorne: Aldine de Gruyter; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubington E, Weinberg MS. Social problems and sociology. In: Rubington E, Weinberg MS, editors. The Study of Social Problems: Seven Perspectives. 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitsuse JI, Spector M. Toward a sociology of social problems. Soc Probl. 1973;20:407–19. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewenstein BV. Science and the media. In: Jasanoff S, Markle GE, Petersen JC, Pinch T, editors. Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. pp. 343–60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleck L. In: Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. Bradley F, Trenn TJ, translators. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry Use of opioids in the treatment of chronic, non-malignant pain. < www2.aaap.org/sites/default/files/Use%20of%20Opioids%20in%20Chronic%20Pain%20Treatment%2C%202009.pdf?phpMyAdmin=H6N%2CWzwzCJE-qgHtALaDIa7GNj5> (Accessed February 4, 2010).

- 19.American Academy of Pain Medicine The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. A consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain (American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel) J Pain. 2009;10:113–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dworkin R, O’Connor A, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: Evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132:237–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States Model Policy for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain. < www.fsmb.org/pdf/2004_grpol_Controlled_Substances.pdf> (Accessed on February 4, 2010).

- 23.Hawaii Board of Medical Examiners Pain Management Guidelines. < http://hawaii.gov/dcca/pvl/news-releases/medical_announcements/pain_management_guidelines.pdf/at_download/file> (Accessed on February 4, 2010). [PubMed]

- 24.Jovey RD, Ennis J, Gardner-Nix J, et al. Use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain – a consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society, 2002. Pain Res Manag. 2003;8(Suppl A):3A–14A. doi: 10.1155/2003/436716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pergolizzi J, Böger RH, Budd K, et al. Opioids and the management of chronic severe pain in the elderly: Consensus statement of an International Expert Panel with focus on the six clinically most often used World Health Organization Step III opioids (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone) Pain Pract. 2008;8:287–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2008.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savage S, Covington EC, Gilson AM, Gourlay D, Heit HA, Hunt JB. Public Policy Statement on the Rights and Responsibilities of Healthcare Professionals in the use of Opioids for the Treatment of Pain: A consensus document from the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the American Pain Society, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine. < www.ampainsoc.org/advocacy/pdf/rights.pdf> (Accessed on February 4, 2010).

- 27.Trescot A, Boswell M, Atluri S, et al. Opioid guidelines in the management of chronic non-cancer pain. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians. Pain Physician. 2006;9:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.University of Michigan Health System . Managing chronic non-terminal pain including prescribing controlled substances. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Health System; < www.cme.med.umich.edu/iCME/pain/default.asp (Accessed on February 4, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group Interagency guideline on opioid dosing for chronic non-cancer pain: An educational pilot to improve care and safety with opioid treatment. < www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/OpioidGdline.pdf> (Accessed on February 4, 2010).

- 30.World Health Organization Achieving Balance in National Opioids Control Policy: Guidelines for Assessment. WHO/EDM/QSM/2000.4. < www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/publicat/00whoabi/00whoabi.pdf> (Accessed on February 4, 2010).

- 31.Furlan AD, Reardon R, Weppler C. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: A new Canadian practice guideline. CMAJ. 2010;182:923–30. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]