Abstract

Objective

To determine the features predictive of time-to-integument damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) from a multiethnic cohort (LUMINA).

Methods

SLE LUMINA patients (n=580), age ≥16 years, disease duration ≤5 years at baseline (T0), of African American, Hispanic and Caucasian ethnicity were studied. Integument damage was defined per the SLICC damage index (scarring alopecia, extensive skin scarring and skin ulcers lasting at least six months); factors associated with time-to-its occurrence were examined by Cox proportional univariable and multivariable (main model) hazards regression analyses. Two alternative models were also examined; in model 1 all patients, regardless of when integument damage occurred (n=94), were included; in model 2 a time-varying approach (GEE) was employed.

Results

Thirty-nine (6.7%) of 580 patients developed integument damage over a mean (SD) total disease duration of 5.9 (3.7) years and were included in the main multivariable regression model. After adjusting for discoid rash, nailfold infarcts, photosensitivity and Raynaud’s phenomenon (significant in the univariable analyses), disease activity over time [Hazard ratio (HR)=1.17; 95% Confidence interval (CI) 1.09–1.26)] was associated with a shorter time-to-integument damage whereas hydroxychloroquine use (HR=0.23, 95% CI 0.12–0.47) and Texan-Hispanic (HR=0.35; 95% CI 0.14–0.87) and Caucasian ethnicities (HR=0.37; 95% CI 0.14–0.99) were associated with a longer time. Results of the alternative models were consistent with those of the main model albeit in model 2 the association with hydroxychloroquine was not significant.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that hydroxychloroquine use is possibly associated with a delay in integument damage development in patients with SLE.

Keywords: Integument, skin, lupus, LUMINA Hispanics, African Americans, damage, hydroxychloroquine

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a protean autoimmune disease characterized by periods of disease activity and quiescence; with time, damage is accrued either as a consequence of the disease or its treatments.

Integument involvement in SLE can be present in up to 93% of patients over their disease course (1;2); these manifestations are heterogeneous ranging from mild to severe and may lead to permanent scarring (damage). Damage in SLE is ascertained with the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Damage Index (SDI) (3); integument damage, as measured by the SDI, has been reported to occur in about 4% to 14% of SLE patients depending on disease duration (1;4). Some authors have found it to be the most common domain of the SDI affected and have proposed that frequent exposure to ultraviolet light, a low socioeconomic status and the patients’ ethnic background may contribute to its occurrence (5–7).

Although integument damage does not have an impact on the patients overall survival, it has other important consequences; extensive scarring, skin ulcers and scarring alopecia affect the patients’ sense of well being, their body image and quality of life leading to difficulties in their social adjustment (shame, humiliation, isolation and self-perceived discrimination), depression and possible negative health behaviors (8;9). Furthermore, skin involvement in lupus represents a significant economic burden with a total health care cost estimated to have been over $500 million in the US for the year 2004 (10).

Utilizing the extensive database of the LUMINA cohort, we have now examined the predictors of time-to-integument damage in this US multiethnic cohort of SLE patients. We hypothesized that, over and above the occurrence of skin involvement, integument damage will be associated with higher levels of disease activity, and that medications and/or other factors (autoantibodies, genetic factors, environmental exposures, among others) may play a role in the pace in which it occurs.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

As previously described, the LUMINA cohort (2;11) was established in 1994 to elucidate the underlying causes of the discrepant disease outcomes observed among SLE patients of different ethnic background in the US. Prior to patient enrollment investigators were trained in the application of all instruments to be utilized, but particularly of the activity and damage instruments (vide infra). Investigators joining the research team subsequently were similarly trained.

Patients have been recruited from different centers [The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTH) and the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus (UPR)]; the LUMINA study has been approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions according to the declaration of Helsinki for research in humans.

The cohort is currently comprised of 635 patients of different ethnic background [(Hispanics, African Americans and Caucasians) who meet at least four of the updated and revised American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE (12;13) and have a disease duration of ≤5 years. All patients complete a series of questionnaires and undergo a physical examination and laboratory testing at each visit. After enrollment (T0), follow-up visits are performed at 6-month intervals during the first year (T0.5 and T1 respectively), and yearly thereafter. Data for missed study visits are obtained, whenever possible, by review of all available medical records. Patients who developed integument damage on or before T0 were not included (n=55) in the main analyses since the precise time at which integument damage occurred could not be defined as the SDI was obtained for the first time at T0.

For patients who developed integument damage after T0, their observation time was truncated at the time of its occurrence; thus the last visit (TL) for these patients was the time at which integument damage first occurred. For those patients who did not develop integument damage, TL was the actual time of their last visit.

Variables

As previously described (2), the LUMINA database includes variables from the socioeconomic-demographic, clinical, immunological, behavioral and psychological domains. With the exception of the genetic and other laboratory variables which are only obtained at T0, all other variables are ascertained at T0 and at every subsequent visit. Only the variables included in this study will be described.

Integument damage was considered our primary end-point, and it was defined as per the SDI (3) if one or more of the following manifestations lasting at least six months occurred: scarring alopecia, extensive skin scarring and skin ulcers. Of importance, these manifestations were not scored if ongoing inflammatory changes were present, despite meeting the duration criterion.

Variables from the socioeconomic-demographic domain included were age, gender, ethnicity, education, poverty (as defined by the US Federal Government adjusted for the number of subjects in the household) (14) and smoking.

Within the clinical variables, disease manifestations, disease activity and damage, immunological variables and medications were included. Cumulative clinical manifestations were examined as per the ACR SLE classification criteria (12;13); other manifestations considered to be important for our final end-point such as alopecia, nailfold infarcts, vasculitic skin lesions and Raynaud’s phenomenon were also evaluated. In addition to the ACR definition of renal disorder, we also examined lupus nephritis defined by: (1). a renal biopsy demonstrating WHO, class II–V histopathology; and/or (2). proteinuria ≥ 0.5 g/24h or 3+ proteinuria attributable to SLE; and/or (3). one of the following features also attributable to SLE and present on two or more visits, done at least 6 months apart: proteinuria ≥ 2+, serum creatinine ≥ 1.4 mg/dl, creatinine clearance ≤ 79 ml/min, ≥ 10 RBCs or WBCs per high power field (HPF), ≥ 3 granular or cellular cast per HPF (15). Comorbidities including hypertension [defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg on two or more occasions and/or patient self-reported intake of antihypertensive medications regardless of cause; if agents are taken for proteinuria (ACE inhibitors), and/or for Raynaud’s phenomenon, hypertension is not recorded], claudication and venous or arterial peripheral thrombotic events were also examined. Baseline C-reactive protein (CRP) serum levels, measured as high-sensitivity CRP by immunometric assay (Immulite 2000; Diagnostic Products, Los Angeles, CA), were also included in these analyses.

Disease activity was assessed using the Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised (SLAM-R) (16) at T0 and over time from T0 to TL. In addition, the variable SLAM-R integument was defined as the sum of the different skin abnormalities included in the instrument (oral/nasal ulcers, periungeal erythema, malar rash, photosensitive rash, nailfold infarcts, alopecia, erythematosus macular or papular rash, discoid lupus, lupus profundus, bullous lesions, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, urticaria, palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, skin ulcer or panniculitis ); this variable was also examined at T0 and over time (T0 to TL).

Damage was measured with the SDI (3) at T0 and it was examined as a continuous variable (total damage score); this index documents cumulative and irreversible damage in 12 different organ systems regardless of its cause (disease activity, medication or intercurrent illness). To be scored, each manifestation must be present at least six months, unless otherwise noted in the instructions accompanying this instrument. The total damage score is the sum of these items with a maximum score of 46. For the purpose of these analyses, the integument domain items were excluded from the SDI total score.

The following autoantibodies were included in these analyses, anti-double-stranded DNA [anti-dsDNA, by immunofluorescence against Crithidia luciliae (normal <1:10)] (17), anti-Smith, anti-RNP, anti-La and anti-Ro (by counter immunoelectrophoresis against human spleen and calf thymus extract) (18) and IgG and IgM antiphospholipid antibodies [(aPL, abnormal >13 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units/ml and/or >13 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units/ml, by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbents assay (ELISA) technique] (19) and the lupus anticoagulant (LAC) (Staclot Test Diagnostica Stago 92600, Asnières-Sur-Seine, France) (20). Patients were considered to be aPL positive if they exhibited abnormal levels of IgM and/or IgG aPL antibodies and/or LAC positivity. All antibodies were obtained at T0 except for LAC and anti-dsDNA that were assessed at each visit.

From the genetic domain, selected HLA-DRB1 (HLA-DRB1*1503, HLA-DRB1*0301, HLA-DRB1* 08) specificities were included.

Medication variables included were the cumulative treatment exposure to hydroxychloroquine, low dose aspirin, non-selective and selective non-steroidal antinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), statins, glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Glucocorticoid exposure was included as either the average or the maximum dose (in mg of prednisone per day). In all cases treatment exposure was considered from TD up to the time integument damage occurred or up to TL for those in whom integument damage had not occurred. That was also the case for hydroxychloroquine intake.

Behavioral and psychological variables included were helplessness (ascertained with the Rheumatology Attitude Index) (21), social support [assessed with the International Support Evaluation List (ISEL)] (22) and abnormal illness-related behaviors [assessed with the Illness Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ)] (23).

Statistical Analyses

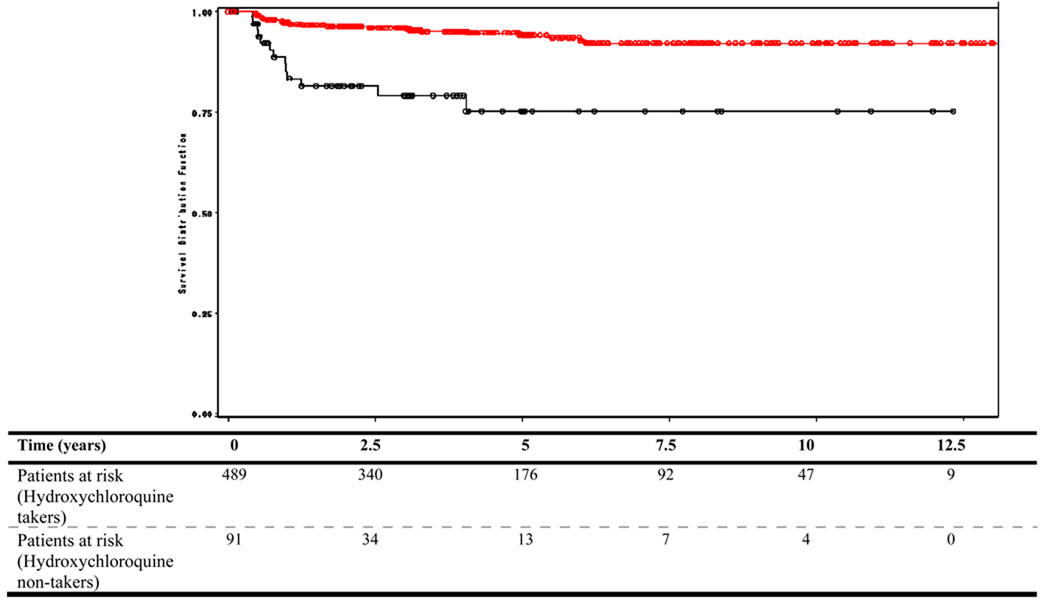

All variables described above were examined by Cox univariable hazards regressions. Variables with a p ≤0.10 in these analyses were entered into a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model. A reduced or parsimonious model was generated to improve the precision of the estimates until no additional variables were significant at p≤ 0.05. Results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). HRs > 1 indicate a shorter time to the event (integument damage) while values < 1 indicate a longer time. Two alternative models were also examined. In model 1, all patients who developed integument damage (n=94) were included; in this case the assumption was made a priori as to when between TD and T0 integument damage had occurred; hydroxychloroquine intake was assumed to have occurred prior to the event if recorded at or immediately after TD but assumed to have not occurred, if otherwise. In model 2, time-varying analyses (generalized estimated equation) were performed to account for changes over the duration of follow up of both hydroxychloroquine intake and the independent variables; in this case, odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% CI rather than HRs were computed. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve as a function of hydroxychloroquine use was also examined.

Results

Six hundred thirty-five patients constituted the LUMINA cohort at the time these analyses were performed; fifty-five of them were excluded as they had already experienced integument damage on or before T0; thus 580 patients were studied. Nearly 90% of the patients were women, their mean age (standard deviation, SD) was 36.5 (12.6) years whereas their mean total disease duration (SD) and follow up times were 5.9 (3.7) and 4.4 (3.3) years, respectively. There were: 113 (19.5%) Texan-Hispanics, 97 (16.7%) Puerto Rican-Hispanics, 201 (34.7%) African Americans and 169 (29.1%) Caucasians. Thirty-nine (6.7%) of the 580 patients had developed integument damage; their mean (SD) age and disease duration were 35.5 (13.0) and 7.4 (3.9) years, respectively. There was a higher proportion of women in this group as compared to the entire cohort (97.7%). All ethnic groups were represented but African Americans had a higher frequency of integument damage (56.4%) than patients in the other groups. The most frequent damage item recorded was alopecia which occurred in 41% of the patients; it was followed by extensive skin scarring in nearly 36% and skin ulcers in about 13%. In the remaining 10% of the patients two (8%) or three (2%) damage items were recorded concomitantly.

Univariable Analyses

With the exception of smoking which was of borderline statistical significance, none of the other socioeconomic-demographic variables were associated either with a shorter or a longer time-to-integument damage. The same was the case for the psychological and behavioral variables. The corresponding HRs and 95% CIs for these variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic-demographic and Behavioral and Psychological Variables Associated with Time-to-Integument Damage Occurrence in LUMINA* Patients by Univariable Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Analyses

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at T0 †, years | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.6750 |

| Gender, female | 4.27 | 0.59–31.13 | 0.1520 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Texan-Hispanic | 0.89 | 0.29–2.79 | 0.8431 |

| Puerto Rican-Hispanic | Reference group | ||

| African American | 1.80 | 0.72–4.50 | 0.2072 |

| Caucasian | 0.46 | 0.14–1.50 | 0.1966 |

| Education, years | 0.94 | 0.85–1.04 | 0.2037 |

| Poverty ‡ | 1.25 | 0.64–2.45 | 0.5201 |

| Smoking | 0.86 | 0.34–2.21 | 0.0943 |

| Social support § | 0.93 | 0.78–1.10 | 0.3920 |

| Abnormal illness-related behaviors § | 1.03 | 0.98–1.08 | 0.2701 |

| Learned helplessness§ | 1.01 | 0.96 – 1.06 | 0.7839 |

Lupus in Minorities: Nature vs Nurture;

baseline;

as per US Federal government guidelines, adjusted for the number of persons in the household;

ascertained with the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, the Illness Behavior Questionnaire and the Rheumatology Altitude Index respectively.

Within the clinical features, discoid rash and nailfold infarct were associated with a shorter time-to-integument damage; in contrast, photosensitivity and Raynaud’s phenomenon were associated with a longer time-to its occurrence although photosensitivity did not quite reach statistical significance. Disease activity as measured by the SLAM-R, whether at T0 or over time as well as the integument domain of the SLAM-R at T0 and over time were associated with a shorter time-to-integument damage occurrence. Damage as measured by the SDI at T0 was also associated with a shorter time-to-integument damage. HLA-DRB1*1503 was associated with a shorter time-to-integument damage whereas the presence of any aPL antibody was associated with a longer time but these associations were only of borderline statistical significance. The corresponding HRs and 95% CIs, for these variables are shown in Table 2. Other autoantibodies, HLA specificities, CRP serum values and all comorbidities examined were not associated with either a shorter or a longer time-to-integument damage (data not shown).

Table 2.

Clinical, Genetic and Therapeutic Variables Associated with Time-to-Integument Damage Occurrence in LUMINA* Patients by Univariable Cox Proportional Hazards Regressions

| Variable | Hazard Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria and non-ACR criteria manifestations |

|||

| Discoid rash | 2.25 | 1.09–4.64 | 0.0276 |

| Alopecia | 1.36 | 0.69–2.69 | 0.3717 |

| Nailfold infarcts | 3.10 | 1.10–8.74 | 0.0327 |

| Vasculitis skin lesions | 1.78 | 0.81–3.93 | 0.1524 |

| Photosensitivity | 0.56 | 0.29–1.05 | 0.0718 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 0.45 | 0.24–0.36 | 0.0153 |

| Arthralgia / Arthritis | 0.42 | 0.10–1.73 | 0.2263 |

| Lupus nephritis | 1.70 | 0.89–3.27 | 0.1094 |

| Seizures | 0.51 | 0.12–2.11 | 0.3494 |

| Comorbities | |||

| Hypertension | 0.54 | 0.25–1.14 | 0.1031 |

| SLAM-R† | |||

| Baseline | 1.12 | 1.07–1.16 | <0.0001 |

| Average | 1.21 | 1.13–1.30 | <0.0001 |

| Integument domain, baseline | 1.79 | 1.43–2.24 | <0.0001 |

| Integument domain, average | 4.67 | 3.22–6.38 | <0.0001 |

| aPL‡ antibodies | 0.45 | 0.21–1.07 | 0.0751 |

| HLA-DRB1*1503 | 2.07 | 1.00–4.30 | 0.0506 |

| SDI § score at baseline | 1.21 | 3.32–7.17 | <0.0001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0.22 | 0.11–0.42 | <0.0001 |

| Aspirin | 0.34 | 0.12–0.96 | 0.0412 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| Non-selective | 0.36 | 0.19–0.70 | 0.0022 |

| Selective | 0.14 | 0.03–0.57 | 0.0064 |

| Statins | 0.14 | 0.02–0.99 | 0.0485 |

Lupus in Minorities: Nature vs Nurture;

Systemic Activity Measure-Revised;

IgM and/or IgG anti-phospholipid antibodies and/or the lupus anticoagulant;

SLICC (Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics) Damage Index (without integument domain items).

As for the pharmacological treatment variables, hydroxychloroquine, aspirin, selective and non-selective NSAIDs and statins were all associated with a longer time-to-integument damage occurrence. The corresponding HRs and 95% CIs, for these variables are also shown in Table 2. All other medications examined were not significant in these analyses (data not shown).

Multivariable analyses

Table 3 shows the results of both the full and reduced multivariable models with the corresponding HRs and 95% CIs. In the final (reduced or parsimonious) model and after adjusting for integument manifestations (discoid rash, nailfold infarcts, photosensitivity and Raynaud’s phenomenon), Texan-Hispanic and Caucasian ethnicities (HR=0.35; 95% CI 0.14–0.87 and HR=0.37; 95% CI 0.14–0.99, respectively) and hydroxychloroquine use (HR=0.23; 95% CI 0.12–0.47) were associated with a longer time-to-integument damage whereas disease activity over time (HR=1.17; 95% CI 1.09–1.26) was associated with a shorter time. In alternative model 1, the effect of hydroxychloroquine was also present (HR=0.47; 95% CI 0.26–0.83) but smoking (HR=2.02; 95% CI 1.08–3.77) and African American ethnicity (HR=3.42; 95% CI 1.60–7.34) were statistically significant and associated with a shorter time to integument damage occurrence. In alternative model 2, however, the effect of hydroxychloroquine remained but statistical significance was not attained (HR= 0.71; 95% CI 0.37–1.37). African American ethnicity was significant in this model (HR= 3.21; 95% CI 1.22–8.45) but smoking was not.

Table 3.

Variables Independently Associated with Time-to-the Occurrence of Integument Damage by Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Regressions in LUMINA* Patients

| Model | Full | Reduced | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

p value | Hazard Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

p value |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.98–1.05 | 0.4295 | |||

| Gender | 2.21 | 0.28–17.82 | 0.4589 | |||

| Ethnicity† | ||||||

| Texan-Hispanic | 0.25 | 0.07–0.83 | 0.0231 | 0.35 | 0.14–0.87 | 0.0246 |

| Caucasian | 0.57 | 0.16–2.05 | 0.3896 | 0.37 | 0.14–0.99 | 0.0471 |

| Clinical Manifestations | ||||||

| Discoid rash | 2.06 | 0.77–5.48 | 0.1531 | |||

| Nailfold infarct | 5.52 | 1.64–18.61 | 0.0057 | 3.05 | 1.02–9.13 | 0.0468 |

| Photosensitivity | 0.78 | 0.34–1.82 | 0.5816 | |||

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 0.39 | 0.16–0.92 | 0.0325 | |||

| SLAM-R‡ average | 1.24 | 1.12–1.34 | <0.0001 | 1.17 | 1.09–1.26 | <0.0001 |

| aPL§ antibodies | 0.68 | 0.28–1.66 | 0.3956 | |||

| HLA-DRB1*1503 | 1.27 | 0.47–3.43 | 0.6428 | |||

| SDI¶ baseline | 0.91 | 0.61–1.35 | 0.6201 | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0.45 | 0.19–1.06 | 0.0688 | 0.23 | 0.12–0.47 | <0.0001 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | ||||||

| Selective | 0.27 | 0.03–2.16 | 0.2168 | |||

| Non-Selective | 0.60 | 0.25–1.47 | 0.2625 | |||

| Low dose aspirin | 0.16 | 0.02–1.43 | 0.1003 | |||

| Statin | 0.39 | 0.05–3.13 | 0.3724 | |||

Lupus in Minorities: Nature vs Nurture;

African Americans and Puerto Rican Hispanics are the reference group;

Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised;

IgG and/or IgM anti-phospholipid antibodies and/or the lupus anticoagulant;

SLICC Damage Index (without the integument domain items). Only the data for the variables retained in the parsimonious model are presented.

Hydroxychloroquine exposure and survival analyses

Four-hundred and eighty-nine patients (84.3%) had been exposed to hydroxychloroquine. Exposure was more frequent among those patients who had not developed integument damage (85.8%) than in those who had developed it (66.7%) and this difference was significant p=0.0015); the mean daily dose was, however, comparable in the two groups (~350 mg per day). The cumulative probability of developing integument damage at five years for hydroxychloroquine-takers was 5% compared to 24% for the non-takers (p<0.0001 by the Log rank test) (Figure 1). The estimates beyond five years are based on relative few patients exposed to the risk and thus they lack precision.

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of developing integument-damage in LUMINA patients by Kaplan-Meier survival curve as a function of hydroxychloroquine intake. Table below shows the number of patients at risk at each time point.

Discussion

In this study we have shown that, when other factors are taken into account to adjust for confounding, the use of hydroxychloroquine is possibly associated with a delay in the onset of integument damage in patients with SLE, an observation which has not been made before and which may have practical implications for the management of our lupus patients. Our results were consistent regardless of the models examined albeit statistical significance was not attained when time-varying analyses were performed; this may be related to a greater degree of missing variables using this approach than when only the baseline variables and hydroxychloroquine use prior to the event were considered; alternatively, this may indicate that early treatment with hydroxychloroquine and personal and disease-related characteristics early in the disease course may have lasting consequences on its outcome. Although it can be argued that we have not properly adjusted for confounding since propensity score analyses were not performed, regression models provide comparable results and thus inferences derived using them should be considered adequate (24;25). Given the observational nature of our study, and the fact that not all patients were treated by study investigators, some patients had not received hydroxychloroquine over the duration of their disease; although this is not what would have been desirable, it takes some time to change prescribing habits. We do hope that this study and others may help all providers involved in the care of lupus patients to uniformly prescribe this drug whose beneficial effects in lupus are well documented (vide infra).

Although integument manifestations usually represent mild-to-moderate SLE, and they are unlikely to affect the long-term outcome of the disease, skin lesions that result in permanent damage affect the patients’ body image and self-esteem and may have devastating personal consequences. It is therefore imperative to recognize the factors predictive of such irreversible changes if they are going to be prevented. We have now conducted for the first time such a study utilizing the extensive database of the LUMINA cohort. In our multiethnic cohort, after a mean of 4.4 years of follow-up, nearly 7% of our patients had developed new integument damage; we have found that, over and above the presence of integument manifestations, higher levels of disease activity were associated with a shorter time-to-integument damage occurrence whereas hydroxychloroquine was associated with a longer time. Of interest, in alternative analyses 1, previously presented as preliminary and in which patients who experienced integument damage on or before TD (prevalent cases) were also included the results were comparable (26); in this model, smoking was also significantly associated with a shorter time-to-integument damage occurrence, which may have some clinical applicability. The fact that so many of our patients developed integument damage relatively early in the course of the disease is not at all uncommon in non-Caucasian lupus patients as noted by Cooper et al (27), Guarize et al (7), Vilar et al (6) and by us a few years ago (28) ; this, however, had not been observed in cohorts constituted by patients of different ethnic background as noted by Gladman et al (29), Chambers et al (30), Mok et al (31), Zonana-Nacash et al (32) and Rivest et al (33).

Numerous benefits of antimalarials have been described in patients with SLE including a decrease in disease flares (34), damage accrual (35;36) and improved survival (37); although in the past these compounds were used primarily for the treatment of patients with mild SLE (integument and articular involvement), they are now recommended for all SLE patients (38). This protective effect probably relates to the wide array of anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and antithrombotic properties antimalarials have. In addition, antimalarials also delay ultraviolet light absorption and have been associated with a reduction in the number of skin antigen-presenting cells (39;40). Finally, given that smoking interferes with the hepatic metabolism of antimalarials via the cytochrome P450 enzyme (41), their beneficial effects, as already discussed, may be significantly reduced if patients smoke.

Not surprising was the fact that disease activity was associated with a shorter time to integument damage given that it has been previously shown to be associated with damage overall and damage in other specific domains of this index (28;33;42).

Consistent with previous reports from our cohort (28) and from others (1;7;33), we found that African Americans were more likely to develop integument damage than Caucasians and Hispanics; in the multivariable analyses, Texan-Hispanic and Caucasian ethnicities were associated with a longer time to the development of integument damage supporting, to certain extent, the association of African American ethnicity with a shorter time to the occurrence to integument damage. Furthermore, African American ethnicity was significant in both sets of alternative analyses. Although discoid lupus and HLA-DRB1*1503, both occurring more frequently in African Americans, were associated with a shorter time-to-integument damage in the univariable analyses neither variable was retained in the multivariable models examined.

Our study is not without limitations. Firstly, we recorded integument damage using the SDI rather than the Cutaneous LE Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI) in which the extent of the disease in specific anatomic areas is weighted as a function of the areas that patients are most concerned about such as the face, scalp, neck and extremities (43); however, this instrument, first published in 2005, was not even developed by the time the LUMINA study started and even though it has been adopted by most specialized dermatology centers caring for lupus patients, that has not been the case for most rheumatology lupus centers and clinics, including ours. Secondly, the possible contribution of environmental factors, such as exposure to UV light, use of sun blockers, infections, solvents, pesticides and hair dyes has not been examined as these variables are not part of the LUMINA database. Thirdly, we were unable to confirm the possible contribution of smoking to integument damage as noted in the analyses in which all patients who developed integument damage (prevalent and incident) were included; whether this is an spurious association or not remains to be determined (26). Fourthly, definitive conclusions about the role of auto-antibodies in the development of integument damage cannot be established given that they had been obtained only at patients’ recruitment into the study. Fifthly, we were not able to examine the exact dose and treatment duration required for hydroxychloroquine to exert its protective effect although the average dose was comparable for those hydroxychloroquine-takers who developed and those who did not develop integument damage. Sixthly, like in other longitudinal studies, some degree of attrition of cohort members had occurred either because of death or loss to follow up; although we have previously shown that loss to follow up does not occur at random (e.g African Americans and patients with active disease are more likely to be loss to follow up), we have handled these patients’ data as uniformly done in Cox analyses; if anything the loss of some patients with these characteristics may have dampened somewhat our results. Also some degree of missingness does occur in longitudinal studies which may have affected our results, particularly of model 2 in which this was more evident. Finally, although damage accrual in SLE has been associated with increased in direct health care costs (44) we did not have the data necessary to corroborate these findings in our cohort.

In summary, our findings highlight the importance of hydroxychloroquine in retarding the development of integument damage, another possible beneficial effect of this medication; this finding may have practical implications for the management of SLE patients. Future studies should ascertain the role of other environmental factors possibly associated with the occurrence of integument damage and develop strategies aimed at preventing them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge all LUMINA patients without whom this study would have not been possible, our supporting staff (Jigna M. Liu, M.P.H. and Ellen Sowell, A.A. at UAB, Carmine Pinilla-Díaz, M.T. at UPR and Robert Sandoval B.A. at UTH) for their efforts in securing our patients’ follow-up and performing other LUMINA-related tasks and Ms. Maria Tyson, A.A. for her expert assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. We also gratefully acknowledge Drs. Victoria P. Werth, Ramon Fernández Bussy and Gene V. Ball for their most helpful comments to an earlier version of this manuscript.

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases P01 AR49084, General Clinical Research Centers M01-RR02558 (UTH) and M01-RR00032 (UAB) and from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR/NIH) RCMI Clinical Research Infrastructure Initiative (RCRII) 1P20RR11126 (UPR) and by the STELLAR (Supporting Training Efforts in Lupus for Latin American Rheumatologists) Program funded by Rheuminations, Inc (UAB). The work of LAG was also supported by Universidad de Antioquía, Medellín, Colombia.

Reference List

- 1.Petri M. Dermatologic lupus: Hopkins Lupus Cohort. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17(3):219–227. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alarcon GS, Friedman AW, Straaton KV, Moulds JM, Lisse J, Bastian HM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: III. A comparison of characteristics early in the natural history of the LUMINA cohort. LUpus in MInority populations: NAture vs. Nurture. Lupus. 1999;8:197–209. doi: 10.1191/096120399678847704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, Fortin P, Liang M, Urowitz M, et al. The development and initial validation of the systemic lupus international collaborating clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:363–369. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Rahman P, Ibanez D, Tam LS. Accrual of organ damage over time in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(9):1955–1959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soares M, Reis L, Papi JA, Cardoso CR. Rate, pattern and factors related to damage in Brazilian systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus. 2003;12(10):788–794. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu447xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vilar MJ, Bezerra EL, Sato EI. Skin is the most frequently damaged system in recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a tropical region. Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24(4):377–380. doi: 10.1007/s10067-004-1041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guarize J, Appenzeller S, Costallat LT. Skin damage occurs early in systemic lupus erythematosus and independently of disease duration in Brazilian patients. Rheumatol Int. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Norton Y, Lyons AC, Douglas KM, Erb N, et al. 'Concealing the evidence': the importance of appearance concerns for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2006;15(8):532–540. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2310xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert P. The evolution of social attractiveness and its role in shame, humiliation, guilt and therapy. Br J Med Psychol. 1997;70(Pt 2):113–147. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, Weinstock MA, Goodman C, Faulkner E, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vila LM, Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Friedman AW, Baethge BA, Bastian HM, et al. Early clinical manifestations, disease activity and damage of systemic lupus erythematosus among two distinct US Hispanic subpopulations. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(3):358–363. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S.Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. Washington, DC: Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division; Current population reports, Series P-23, No. 28 and Series P-60, No. 68 and subsequent years. 1995

- 15.Bastian HM, Roseman JM, McGwin G, Jr, Alarcón GS, Friedman AW, Fessler BJ, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: XII. Risk factors for lupus nephritis after diagnosis. Lupus. 2002;11:152–160. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu158oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang MH, Socher SA, Larson MG, Schur PH. Reliability and validity of six systems for the clinical assessment of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1107–1118. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aarden LA, De Groot ER, Feltkamp TE. Immunology of DNA. III. Crithidia luciliae, a simple substrate for the determination of anti-dsDNA with the immunofluorescence technique. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1975;254:505–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb29197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton RG, Harley JB, Bias WB, Roebber M, Reichlin M, Hochberg MC, et al. Two Ro (SS-A) autoantibody responses in systemic lupus erythematosus. Correlation of HLA-DR/DQ specificities with quantitative expression of Ro (SS-A) autoantibody. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(4):496–505. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris EN. Special report. The second international anti-cardiolipin standardization workshop/the Kingston anti-phospholipid antibody study (KAPS) group. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94(4):476–484. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/94.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Triplett DA, Barna LK, Unger GA. A hexagonal (II) phase phospholipid neutralization assay for lupus anticoagulant identification. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70(5):787–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engle EW, Callahan LF, Pincus T, Hochberg MC. Learned helplessness in systemic lupus erythematosus: Analysis using the Rheumatology Attitude Index. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:281–286. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HN. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilowsky I. Dimensions of illness behavior as measured by the Illness Behavior Questionnaire: A replication study. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90123-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmoor C, Caputo A, Schumacher M. Evidence from nonrandomized studies: a case study on the estimation of causal effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(9):1120–1129. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S. A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(5):437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pons-Estel GJ, Gonzalez LA, Zhang J, Vila LM, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS. Smoking is strong predictor of integument damage in patients with lupus: Data from LUMINA Multiethnic US cohort. Lupus. 2008;17:482–483. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper GS, Treadwell EL, St Clair EW, Gilkeson GS, Dooley MA. Sociodemographic associations with early disease damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:993–999. doi: 10.1002/art.22894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Bartolucci AA, Roseman J, Lisse J, Fessler BJ, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. IX. Differences in damage accrual. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2797–2806. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2797::aid-art467>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Rahman P, Ibanez D, Tam LS. Accrual of organ damage over time in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1955–1959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chambers SA, Allen E, Rahman A, Isenberg D. Damage and mortality in a group of British patients with systemic lupus erythematosus followed up for over 10 years. Rheumatology. 2009;48:773–775. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mok CC, Ho CT, Wong RW, Lau CS. Damage accrual in Southern Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zonana-Nacach A, Yanez P, Jimenez-Balderas FJ, Camargo-Coronel A. Disease activity, damage and survival in Mexican patients with acute severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1998;7:119–123. doi: 10.1177/0961203307083175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivest C, Lew RA, Welsing PM, Sangha O, Wright EA, Roberts WN, et al. Association between clinical factors, socioeconomic status, and organ damage in recent onset systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:680–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group. A randomized study of the effect of withdrawing hydroxychloroquine sulfate in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:150–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101173240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molad Y, Gorshtein A, Wysenbeek AJ, Guedj D, Majadla R, Weinberger A, et al. Protective effect of hydroxychloroquine in systemic lupus erythematosus. Prospective long-term study of an Israeli cohort. Lupus. 2002;11:356–361. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu203ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fessler BJ, Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Roseman J, Bastian HM, Friedman AW, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: XVI. Association of hydroxychloroquine use with reduced risk of damage accrual. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1473–1480. doi: 10.1002/art.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Bertoli AM, Fessler BJ, Calvo-Alen J, Bastian HM, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in the survival of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Data from LUMINA, a multiethnic us cohort (LUMINA L) Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1168–1172. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.068676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsakonas E, Joseph L, Esdaile JM, Choquette D, Senecal JL, Cividino A, et al. A long-term study of hydroxychloroquine withdrawal on exacerbations in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group. Lupus. 1998;7(2):80–85. doi: 10.1191/096120398678919778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wozniacka A, Lesiak A, Narbutt J, Kobos J, Pavel S, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A. Chloroquine treatment reduces the number of cutaneous HLA-DR+ and CD1a+ cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2007;16(2):89–94. doi: 10.1177/0961203306075384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sjolin-Forsberg G, Berne B, Eggelte TA, Karlsson-Parra A. In situ localization of chloroquine and immunohistological studies in UVB-irradiated skin of photosensitive patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75(3):228–231. doi: 10.2340/0001555575228231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahman P, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB. Smoking interferes with efficacy of antimalarial therapy in cutaneous lupus. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(9):1716–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mok CC, To CH, Mak A. Neuropsychiatric damage in Southern Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85(4):221–228. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000231955.08350.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albrecht J, Taylor L, Berlin JA, Dulay S, Ang G, Fakharzadeh S, et al. The CLASI (Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index): an outcome instrument for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(5):889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutcliffe N, Clarke AE, Taylor R, Frost C, Isenberg DA. Total costs and predictors of costs in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40(1):37–47. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]