Abstract

Introduction

Activated protein C (APC) inactivates factor VIIIa (FVIIIa) through cleavages at Arg336 in the A1 subunit and Arg562 in the A2 subunit. Proteolysis at Arg336 occurs 25-fold faster than at Arg562. Replacing residues flanking Arg336 en bloc with the corresponding residues surrounding Arg562 markedly reduced the rate of cleavage at Arg336, indicating a role for these residues in the catalysis mechanism.

Materials and Methods

To assess the contributions of individual P4-P3’ residues flanking the Arg336 site to cleavage efficiency, point mutations were made based upon those flanking Arg562 of FVIIIa (Pro333Val, Gln334Asp, Leu335Gln, Met337Gly, Lys338Asn, Asn339Gln) and selected residues flanking Arg506 of FVa (Leu335Arg, and Lys338Ile). APC-catalyzed inactivation of the FVIII variants and cleavage of FVIIIa subunits were monitored by FXa generation assays and Western blotting.

Results

Specific activity values of the variants were 60–135% of the wild type (WT) value. APC-catalyzed rates of cleavage at Arg336 remained similar to WT for the Pro333Val and Lys338Ile variants and was modestly increased for the Asn339Gln variant; while rates were reduced ~2–3-fold for the Gln334Asp, Leu335Gln, Leu335Arg, and Lys338Asn variants, and 5-fold for the Met337Gly variant. Rates for cofactor inactivation paralleled cleavage at the A1 site. APC slowly cleaves Arg372 in FVIII, a site responsible for procofactor activation. Using FVIII as substrate for APC, the Met337Gly variant yielded significantly greater activation compared with WT FVIII.

Conclusions

These results show that individual P4-P3’ residues surrounding Arg336 are in general more favorable to cleavage than those surrounding the Arg562 site.

Keywords: Factor VIII, activated protein C, P4-P3’ residues, mutagenesis, Western blotting

Introduction

Factor VIII plays a central role in blood coagulation, as a deficiency or defects in this protein results in the bleeding disorder hemophilia A. Factor VIII is synthesized in a single chain form [1] and consists of three homologous A domains, two homologous C domains, and a central B domain [2, 3]. Short segments of acidic residues, designated by a lowercase “a”, follow the A1 and A2 domains and precede the A3 domain. Thus the single chain protein is ordered as: A1-a1-A2-a2-B-a3-A3-C1-C2. Post translational processing separates the B and A3 domains, generating the heterodimeric factor VIII composed of a heavy chain (A1-a1-A2-a2-B) and a light chain (a3-A3-C1-C2). Both single chain and heterodimer represent procofactor forms. While the latter is the prominent form in blood, both forms are expressed in near similar amounts in heterologous cells [4]. Factor VIII is activated by thrombin or factor X through cleavage at Arg372 (a1-A2 junction), Arg740 (a2-B junction), and Arg1689 (a3-A3 junction) [4-6]. The result of this proteolysis is generation of the active cofactor, the heterotrimeric factor VIIIa, comprised of subunits designated A1, A2 and A3C1C2. The A1 and A3C1C2 subunits are stably associated while the A2 subunit remains associated through weak electrostatic interactions. Factor VIIIa serves as a cofactor for the serine protease factor IXa, forming the intrinsic factor Xase complex and magnifying catalytic efficiency for the conversion of factor X to factor Xa by several orders of magnitude [4].

Down-regulation of the Xase complex is achieved by two primary mechanisms that both relate to cofactor inactivation [4]. The first is through spontaneous decay of the weak affinity interaction between the A1/A3C1C2 dimer and A2 subunit [7]. The second is through proteolytic inactivation catalyzed by activated protein C (APC), which cleaves at P1 residues Arg336 in the A1 subunit and Arg562 in the A2subunit. Cleavage at Arg336 liberates the a1 segment, shown to be involved in factor X binding [8]. This cleavage reduces the kcat for the Xase complex as well as re-orients the A2 domain, making interactions with factor IX less favorable and increasing the Km for factor X [9]. Cleavage at Arg562 interrupts the 558-loop, which constitutes an important factor IXa interactive site [10]. While cleavage at either site in factor VIIIa appears to be independent of the alternate site, the Arg336 site represents the primary cleavage site and catalysis here occurs at a rate ~25-fold faster than Arg562 [11].

The cleavage mechanism of factor VIII by APC is initiated by exosite-dependent interactions, which govern substrate specificity and affinity [12]. Active site docking of APC to residues flanking substrate cleavage sites appears to be a prime determinant in the rate of catalysis of cleavage at that site. In factor VIIIa, P4-P3’ residues play a prominent role in the rates seen for cleavage at Arg336 and Arg562. Earlier results from our laboratory demonstrated that mutating the P4-P3’ residues flanking Arg336 to those surrounding Arg562 reduced cleavage at the former site by as much as 100-fold [13]. However, experiments mutating individual residues to assess their contributions to cleavage at this site have not been determined. In this study we examine the role of individual residues flanking Arg336 to assess their contributions to the enhanced rate of cleavage at this site. Recombinant factor VIII proteins were prepared based upon P4-P3’ residues flanking Arg562 of factor VIIIa as well as selected residues flanking Arg506 of factor Va. Our results demonstrate differential contributions of individual residues flanking the Arg336 site, that in general are more favorable to cleavage than those residues flanking Arg562. These results further suggest that the flanking residues appear to have a synergistic rather than additive effect on the overall increased rate of cleavage at Arg336.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

The R8B12 monoclonal antibody (GMA-012), that recognizes a discontinuous epitope within the A2 domain [14], and the GMA-8003 monoclonal antibody, that recognizes the C2 domain, were purchased from Green Mountain Antibodies (Burlington, VT). The 58.12 antibody, that recognizes the N-terminal sequence of the A1 domain, was provided by Bayer Corporation (Berkeley, CA). Phospholipid vesicles (20% phosphatidylserine, 40% phosphatidylcholine, 40% phosphatidylethanolamine; Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., Alabaster, AL), human α-thrombin (MP Biomedicals, LLC, Solon, OH), hirudin (Calbiochem, EMD Biosciences Inc., San Diego, CA), factor IXaβ, factor X, and human APC (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN), APC chromogenic substrate (L-pyroglytamyl-L-prolyl-L-arginine-p-nitroanilide hydrochloride; Chromogenix Instrumentation Laboratory S.p.A, Milano, Italy), factor Xa chromogenic substrate, pefa-5523, CH3OCO-D-CHA-Gly-Arg-pNA AcOH; Centerchem, Inc., Norwalk, CT) were purchased from the indicated vendors. The B-domainless factor VIII expression vector (HSQ-MSAB-NotI-RENeo) and the Bluescript II K/S- factor VIII vector were generous gifts from Dr. Pete Lollar and John Healey (Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University, Atlanta, GA).

Construction, Expression and Purification of Recombinant Factor VIII Mutants

Endonucleases Spe I and Sac II were used to remove B-domainless factor VIII from the FVIIIHSQ-MSAB-NotI-RENeo (residues 177-527) expression construct, which was subcloned into the pBluescript II KS- vector. Factor VIII proteins bearing the single point mutations of Pro333Val, Gln334Asp, Leu335Gln, Leu335Arg, Met337Gly, Lys338Ile, Lys338Asn, or Asn339Gln were introduced into shuttle constructs using the Stratagene QuikChange Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit as described previously [15]. Transfection and selection of desired mutant proteins as well as protein expression in BHK cells were performed as described previously [15]. The conditioned medium was collected daily and proteins that were expressed were purified through use of an SP Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway) as previously described [16]. A one-stage clotting assay was used to detect active fractions, which were pooled, and dialyzed against 20mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 0.1M NaCl, 5mM CaCl2, and 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20. Typically, resultant factor VIII forms were >90% pure as determined by SDS-PAGE (8% gels).

ELISA

Concentrations of factor VIII proteins were determined by a sandwich ELISA using GMA-8003 as the capture antibody and biotinylated R8B12 as the detection antibody. Streptavidin-linked horseradish peroxidase (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) with the substrate o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were used to optically determine the amount of bound factor VIII as previously described [15]. Purified commercial factor VIII was used as a standard. Specific activities of factor VIII proteins were determined using ELISA and one-stage clotting assays.

Factor Xa Generation Assay

Factor Xa generation assays were used to assess residual factor VIIIa activity following reaction with APC. The rate of conversion of factor X to Xa was monitored in a purified system [17] as follows. Factor VIII (150 nM) was activated by thrombin (20 nM) in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, and 100 μg/mL BSA. After 2 minutes, thrombin activity was inhibited by addition of hirudin (20 U/mL) and the factor VIIIa product was reacted with APC (3 nM) in the presence of phospholipid vesicles (100 μg/mL). Reactions were run at 37°C. Aliquots were removed at the indicated time points and factor VIIIa was reacted at 22°C with factor IXa (5 nM), and factor X (500 nM) to initiate factor Xa generation. Reactions were quenched by addition of EDTA (50 mM final concentration) at the appropriate times and reacted with the factor Xa chromogenic substrate pefa-5523 (0.46 mM final concentration) to determine the rates of factor Xa generation, which was used to assess residual factor VIII activity. Samples were read at 405 nm for 5 minutes using a VersaMax microtitre plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Parallel experiments run in the absence of APC were used as a control to account for the loss in factor VIIIa activity due to dissociation of the A2 subunit which typically accounted for ~10–15% activity loss over the reaction time course. The relatively high concentration of factor VIII (150 nM) used in reactions with APC minimized this dissociation of A2 subunit.

Western Blotting

Factor VIII (130–500 nM) was activated by thrombin (10–50 nM) as described above. These reaction conditions typically yielded ~80–85% conversion of factor VIII to factor VIIIa as judged by blotting [13]. This value was used to determine substrate concentration for subsequent reactions. The resulting factor VIIIa was reacted with APC (2-5nM) in the presence of phospholipid vesicles (100 μg/mL-500 μg/mL). Aliquots were removed at the indicaed time points and reactions were stopped with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE using 8% polyacrylamide gels and western blotting was done as described previously [17]. The monoclonal antibody 58.12 (anti-A1) or R8B12 (anti-A2) was used to probe the blots, which was followed by a goat anti-mouse alkaline-phosphatase-linked secondary antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The blots were scanned at 570 nm using Storm 860 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) or VersaDocTM Imaging System (BioRad, Hercules, CA) after development using ECF® (enhanced chemifluorescence) system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Band densities were measured using Image Quant (Molecular Devices) or Image Lab (BioRad), depending upon the device employed.

Data Analysis

All experiments shown were performed three or more times on separate occasions and the average values with standard deviations are shown. Analysis of western blots was carried out by densitometry and non-linear least squares regression analysis. Curve fitting was performed using a second order polynomial equation (equation 1), as previously employed [13] to obtain slope values at time zero. This analysis used data from initial time points (up to 5 min) or up to approximately 40% of substrate consumed.

| (Eq. 1) |

Where [FVIIIa] is the factor VIIIa concentration in nM, t is the time in minutes, A is the initial concentration in nM of factor VIIIa , A1 subunit, or A2 subunit, and B is the slope at time zero. Rates of factor VIIIa inactivation, and A1 or A2 cleavage were calculated by dividing the absolute value of B by APC concentration and results are expressed in nM FVIIIa/min/nM APC or nM A1 or A2/min/nM APC [13].

Results

Characterization of recombinant factor VIII proteins

We have previously shown that docking of the APC active site to residues flanking factor VIII cleavage sites makes a substantial contribution to the disparate cleavage rates observed at the P1 residues, Arg336 and Arg562 [13]. That study employed mutating clusters of residues at the P4-P3’ positions en bloc to assess the cumulative effect of the substitutions. The current study was undertaken to assess the roles of individual residues flanking the scissile bonds to catalytic rate. To this end, recombinant factor VIII proteins were prepared containing point mutations replacing P4-P3’ residues surrounding the fast-reacting cleavage site at Arg336 with those residues surrounding the slow-reacting site at Arg562 (see Table 1). Two additional factor VIII variants were prepared that included Leu335Arg and Lys338Ile (Table 1), which represent substitution of the P2 and P2’ residues, respectively, of the fast-reacting site in factor Va, Arg506 [18], for the Arg336 site in factor VIIIa. The rationale for these substitutions was the significant difference in the nature of the side chains (hydrophobic versus basic charged) in relative position in the flanking sequences.

Table 1.

P4-P3’ residues flanking cleavage sites in factors VIIIa and Va

| P4 | P3 | P2 | P1 | P1′ | P2′ | P3′ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVIIIa | Pa | Q | L | R336 | M | K | N |

| FVIIIa | V | D | Q | R562 | G | N | Q |

| FVa | L | D | R | R506 | G | I | Q |

Sequences are indicated using the single letter amino acid designation.

Analysis of purified factor VIII proteins by SDS-PAGE showed >90% purity and bands corresponding to the masses of ~170, ~90, and ~80kDa for the single chain, and heavy and light chains of the heterodimer, respectively (data not shown). Specific activity values for the point mutants were 60–135% of the wild type value (Table 2), indicating that single substitutions of these residues did not appreciably affect the cofactor function of factor VIIIa. In addition, western blot analysis showed similar rates for activation by thrombin, as judged by cleavage of the precursor bands, as compared with wild type factor VIII (results not shown). These results further confirmed that the mutations did not alter factor VIII structure.

Table 2.

Specific activity values for P4-P3’ factor VIII mutants

| Factor VIII | Specific Activity |

|---|---|

| % | |

| WT | 100 ± 26 |

| Pro333Val | 64 ± 2.5 |

| Gln334Asp | 117 ± 3.8 |

| Leu335Gln | 120 ± 25 |

| Leu335Arg | 117 ± 20 |

| Met337Gly | 119 ± 4.0 |

| Lys338Ile | 135 ± 22 |

| Lys338Asn | 121 ± 21 |

| Asn339Gln | 84 ± 9.4 |

Specific activity values are shown as a percentage ± standard deviation of wild type, as described under Materials and Methods. Values are determined from at least three separate determinations.

Inactivation factor VIIIa variants by APC

Rates of cleavage at the Arg336 site were measured using western blotting to quantitate the A1 substrate and A1336 cleavage product. Control experiments were performed in the absence of APC to monitor activity loss that was independent of proteolysis. Under these conditions, we observed ~10-15% losses (approximate rates of 0.4-0.9 nM/min) in factor VIIIa activity for wild type and the majority of the variants following the 20 minute reaction. Values are derived from curve fits for the initial 5 min of the reactions (Figure 1). The presence of residual factor VIIIa activity following prolonged reaction with APC results from the low level of activity observed following complete cleavage at Arg336 [9] and the failure to completely cleave A2 subunit [11]. Mutation of the P4 Pro333 to Val; or the P2’ Lys338 to either Asn or Ile as present flanking the factor VIIIa 562 site or the factor Va 506 site, respectively, showed little effect on the rate of loss of activity when compared with the wild type value. On the other hand, inactivation rates observed for point mutations at the P3 and P2 positions (Gln334Asp, Leu335Gln, and Leu335Arg) were reduced by ~2 fold compared with wild type factor VIIIa, indicating that these residues make a moderate contribution to cleavage at the Arg336 site. The Met337Gly variant exhibited an ~5 fold reduction in rate of inactivation suggesting that Met at the P1’ site is important for catalysis at the Arg336 site. Interestingly, the Asn339Gln variant exhibited a 2-fold increase in inactivation rate, suggesting that the Gln residue found at the P3’ site flanking Arg562 is more favorable for interactions with APC than the Asn flanking Arg336.

Figure 1.

Inactivation of the P4-P3’ factor VIIIa variants by APC. Inactivation rates for WT (●), P333V (■), Q334D (▲), L335Q (○), L335R (□), M337G (◆), K338I (◇), K338N (△), N339Q (X) factor VIIIa were measured (using 150 nM factor VIII) as described in Materials and Methods. Parallel assays were run in the absence of APC in order to correct for factor VIIIa decay independent of APC. Curve fits were applied for the initial time points (up to 5 min, solid lines) and dashed lines show extended time points. Experiments were performed at least three times and standard deviations were within 15 % of mean values.

A1 subunit cleavage of P4-P3’ factor VIIIa variants by APC

Rates of cleavage at the Arg336 site were measured using western blotting to quantitate the A1 substrate and A1336 cleavage product. We previously showed that rates of inactivation correlated with cleavage at this site in the A1 subunit, whereas cleavage at Arg562 in the A2 subunit occurred on a much slower time course and subsequent to the initial rate of loss of activity [11]. Reactions similar to those run above were subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotting using a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the amino terminus of the A1 subunit (Figure 2). Thus both the A1 substrate and cleaved product (A1336) are detected and can be quantitated by scanning densitometry. Non-linear least squares regression analysis, normalized to initial factor VIIIa concentration, was used to calculate the rates of cleavage. In general, results from this analysis paralleled those obtained from assessing changes in cofactor activity. Examination of the wild type protein showed an A1 subunit cleavage rate that was ~2-fold greater than the observed rate of factor VIIIa inactivation. We have observed this temporal disparity before [11, 13] and attributed it to a time-dependent change in conformation and/or loss of a functional fragment following proteolysis.

Figure 2.

A1 subunit cleavage rates of the P4-P3’ factor VIIIa variants. (Panel A) A1 subunit and A1336 product are visualized by western blotting of factor VIIIa proteins using the 58.12 antibody following reaction with APC. (B) Loss of A1 subunit was plotted as a function of time for WT (●), P333V (■), Q334D (▲), L335Q (○), L335R (□), M337G (◆), K338I (◇), K338N (△), N339Q (X) proteins. Curve fits were applied for the initial time points (minimally 5 min, solid lines) and dashed lines show extended time points. Experiments were performed at least three times and standard deviations were within 20 % of the mean.

Consistent with observations for rates of loss of activity, cleavage rates at Arg336 for Gln334Asp, Leu335Gln, and Leu335Arg variants were modestly reduced (up to ~3-fold) compared to wild type indicating a moderate contribution to proteolysis at that site (Table 3). Also similar to the effects observed on activity, the cleavage rate for the Met337Gly variant was reduced ~6-fold, whereas the rate for the Asn339Gln variant was increased by ~2-fold. Furthermore, cleavage rates for Pro333Val and Lys338Ile were similar to that seen for wild type factor VIIIa. Interestingly, a few of the variants, Leu335Gln, Met337Gly and Lys338Asn, showed rates of cleavage at the Arg336 site that were slightly greater than those for cofactor inactivation, suggesting some reduction in the lag time between the two events.

Table 3.

Rates of factor VIIIa inactivation, and A1 subunit (factor VIIIa) and A2 domain (factor VIII) cleavage for P4-P3’ mutants

| Factor VIII(a) | Inactivation | A1 Cleavage (FVIIIa) | A2 Cleavage (FVIII) |

|---|---|---|---|

| nM FVIIIa/min/nM APC | nM A1/min/nM APC | nM FVIII/min/nM APC | |

| WT | 4.6 ± 0.4 (1.0) | 8.3 ± 0.5 (1.0) | 0.11 ± 0.04 (1.0) |

| Pro333Val | 4.9 ± 0.4 (1.1) | 9.3 ± 0.5 (1.1) | 0.12 ± 0.01 (1.1) |

| Gln334Asp | 2.1 ± 0.2 (0.5) | 5.8 ± 1.1 (0.7) | 0.23 ± 0.02 (2.1) |

| Leu335Gln | 2.4 ± 0.3 (0.5) | 2.5 ± 0.3 (0.3) | 0.03 ± 0.003 (0.3) |

| Leu335Arg | 1.7 ± 0.2 (0.4) | 6.1 ± 0.4 (0.7) | 0.01 ± 0.003 (0.1) |

| Met337Gly | 1.0 ± 0.05 (0.2) | 1.5 ± 0.1 (0.2) | 0.04 ± 0.006 (0.4) |

| Lys338Ile | 2.7 ± 0.2 (0.6) | 8.8 ± 0.4 (1.1) | 0.02 ± 0.001 (0.2) |

| Lys338Asn | 3.0 ± 0.1 (0.7) | 4.2 ± 0.5 (0.5) | 0.19 ± 0.03 (1.7) |

| Asn339Gln | 8.6 ± 1.2 (1.9) | 15 ± 2.5 (1.8) | 0.17 ± 0.02 (1.5) |

Factor VIIIa inactivation, factor VIIIa A1 subunit and factor VIII A2 domain cleavage rates were estimated by non- linear least squares regression analysis as determined from results presented in Figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Values represent mean and standard deviations from at least three separate determinations. Values in parentheses are rate values relative to wild type.

Cleavage of variant factor VIII proteins by APC

We have previously determined that mutating either Arg336 [11] or residues flanking this site [13] does not appreciably impact cleavage rate at the Arg562 site in factor VIIIa. Additionally, it has been shown that once dissociated, A2 subunit is a poor substrate for APC [19], which may lead to an inaccurate calculation of rates for Arg562 cleavage in the cofactor. In order to gain insights into the effects of these mutations on proteolysis at the A2 site, we employed the factor VIII procofactor, where the A1 and A2 domains are contiguous, as substrate for APC. Factor VIII (150 nM) was reacted with APC (5 nM) in the presence of phospholipid vesicles (200 μg/mL), subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted using the R8B12 monoclonal antibody, which recognizes a carboxy terminal fragment (A2C) of the A2 domain following cleavage at Arg562 [19]. Blotting revealed two precursor bands (Figure 3 inset, zero time points) representing the single chain factor VIII and the heavy chain of the factor VIII heterodimer, with the latter showing somewhat greater staining intensity. Reaction with APC gave rise to two intermediate sized bands, the higher molecular weight band representing the A2 subunit with contiguous a1 segment (residues 337-372), and designated a1-A2, which is derived from cleavage at Arg336; and the lower molecular weight band representing the A2 subunit derived from cleavage at Arg372. This latter band has been previously observed as a product of APC action on intact factor VIII [11, 13] and is not attributable to exogenous thrombin in the APC preparation since reactions include the presence of hirudin at sufficient levels (10 U/mL) to block the action of nM concentrations of thrombin (data not shown). An A2 terminal digest product is indicated at the bottom of the blot as fragment A2C and represents the fragment of residues 563-740 derived from APC cleavage of the A2 (or a1-A2) subunit(s). The rapid generation of the a1-A2 fragment compared with generation of the A2C fragment in the wild type factor VIII is consistent with faster rates of cleavage at Arg336 compared with Arg562 in this substrate as well as factor VIIIa.

Figure 3.

Factor VIII A2 domain cleavage rates for the P4-P3’ variants. APC cleavage of WT (●), P333V (■), Q334D (▲), L335Q (○), L335R (□), M337G (◆), K338I (◇), K338N (△), N339Q (X) factor VIII was visualized by western blotting using the R8B12 monoclonal antibody. Curve fits for the generation of A2C cleavage product were applied for the initial time points (up to 5 min, solid lines) and dashed lines show extended time points. The inset shows blots for the WT and Met337Gly variant; bands for single chain (SC), heavy chain (HC), A2+a1, A2, and A2c are shown. Experiments were performed at least three times and standard deviations were within 20 % of the mean.

Appearance of the A2C fragment was be used to estimate rates of cleavage at the Arg562 site (Figure 3 and Table 3). Rate of cleavage at this site in the wild type protein is fractional compared with cleavage at the A1 site in factor VIII. The P4 Pro333Val variant showed essentially no effect on cleavage rate at the A2 site, while rates for Gln334Asp, Lys338Asn and Asn339Gln were increased up to ~2-fold. However, other variants, notably Leu335Gln, Leu335Arg, Met337Gly, and Lys338Ile showed significant rate reductions, although rigorous quantitation of these values was difficult due to the overall slow reaction rate and weak staining density of the fragment. With the exception of the Lys338Ile, this latter class of variants all showed reduced rates of cleavage at the Arg336 site in factor VIIIa. This result suggested that substitutions flanking the faster reacting A1 site may influence A2 cleavage when the A1 and A2 domains are contiguous in the factor VIII substrate.

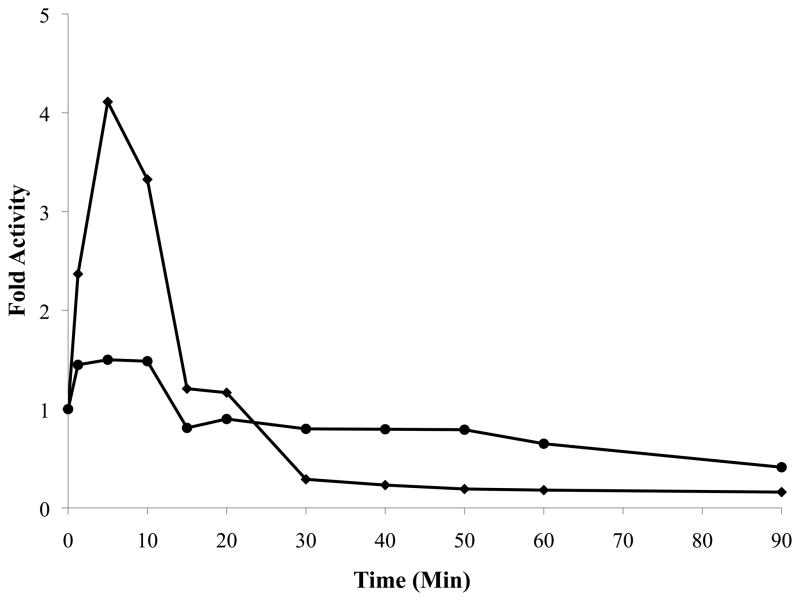

APC-catalyzed activation of Met337Gly factor VIII variant

Examination of the APC-catalyzed cleavage of the factor VIII procofactor (Figure 3) revealed similar rates of appearance of the A2 and a1-A2 bands in the wild type factor VIII sample, suggesting near equivalent rates of cleavage at Arg372 and Arg336, respectively. However, factor VIII variants demonstrating reduced rates of cleavage at the Arg336, thereby resulting in little generation of a1-A2 (e.g. Leu335Gln and Met337Gly) showed essentially no effect on rates of generation of A2 subunit resulting from proteolysis at Arg372. Since cleavage at Arg372 results in procofactor activation, we would predict a transient activation of these variants following reaction with APC. To test this hypothesis, we employed a factor Xa generation assay to monitor factor VIIIa activity. Reactions were run with factor VIII (150 nM), a relatively higher level of APC (30 nM) to facilitate catalysis, and hirudin (10 U/mL) to block any exogenous thrombin in the APC solution. Results obtained with wild type factor VIII were compared with the Met337Gly factor VIII variant, which showed the greatest relative decrease of a1-A2 product (Figure 3). Results from the factor Xa generation assays (Figure 4) showed a modest (~50%) increase in activity for wild type that was transient and slowly decayed over the time course. On the other hand, initial reaction of the variant with APC resulted in an ~4-fold increase in activity that decayed more rapidly than the activity observed for the wild type protein. This more rapid rate of decay for the variant resulted in part from a more rapid rate of A2 subunit dissociation, as indicated by control experiments where the variant factor VIII activated by thrombin demonstrated a more rapid rate of activity decay than was observed following thrombin activation of the wild type factor VIII (data not shown). Overall, this result demonstrated the potential for APC to be a factor VIII “activating” enzyme following selective mutations to reduce the rate of cleavage at the inactivating Arg336 site.

Figure 4.

Changes in activity of WT and Met337Gly factor VIII following reaction with APC. WT (●), M337G (◆) factor VIII (150 nM) were reacted with APC (30 nM) in the presence of phospholipid (200 μg/mL). Activity was measured by factor Xa generation assays. Experiments were performed at least three times and standard deviations were within 15 % of the mean.

Discussion

Activated protein C inactivates factor VIIIa through cleavages at Arg336 in the A1 subunit and Arg562 in the A2 subunit. The prominent cleavage reaction is at Arg336, which occurs at a rate ~25 fold faster than at Arg562 [11]. An earlier study showed that swapping the P4-P3’ sequence surrounding the scissile bond at Arg336 with that from Arg562 resulted in as much as a 100-fold reduction in cleavage rate at Arg336 [13]. In the current study, we examined individual P4-P3’ residues flanking the Arg336 site and their contribution to APC-catalyzed cleavage at this site. Point mutations were introduced within the P4-P3’ residues flanking Arg336 based upon either those flanking the Arg562 site in factor VIIIa or the Arg506 site in factor Va. Results from cleavage and cofactor inactivation rates showed contributions of residues Gln334, Leu335, Met337 and Lys338 to enhancing catalytic efficiency.

While substitution of the P4 Pro333 with Val was largely benign, replacements of both the P3 Gln334 and P2 Leu335 resulted in ~2-fold reductions in the rates of A1 cleavage and cofactor inactivation compared with wild type. Little information is known regarding the nature of S4-S3’ subsites in APC, as well as the optimal P4-P3’ substrate residues for APC cleavage. The S2 pocket is more open in APC [20] compared with other homologous enzymes such as thrombin or factor Xa, and is able to accommodate large, charged or uncharged residues including Leu and Gln in factor VIIIa and Thr and Arg in factor Va. An earlier study demonstrated a significant contribution of the P2 residue in catalysis by APC. Rezaie [21] showed that replacement of the P2 Gly in anti-thrombin with Arg (based on the factor Va P1 Arg506 site) resulted in a 40-fold increase in catalytic rate, indicating the importance of side chain volume at this site for efficient active site engagement. Our results suggest a modest preference for the hydrophobic Leu rather than the polar Gln or basic charged Arg at this position. The S3 site in APC is smaller but more hydrophilic than the S2 site [20]. Mutation of the P3 Gln334 to Asp resulted in a ~2 fold reduction in cleavage at Arg336, indicating a modest preference for the polar residue over the negatively charged one. This result may reflect a repulsive interaction involving Glu192, a critical residue lining the S3 pocket of APC that has been shown to affect substrate specificity [22].

Substitution of individual prime residues following the Arg336-Met337 scissile bond resulted in marked difference effects. Most dramatic was the ~6-fold reduction in cleavage rate when Met337 was replaced with Gly. Inasmuch as little information is available concerning S1’-S3’ subsites in the proteinase, this defect may largely be related to side chain volume affecting active site engagement. Two mutations at the P2’ Lys338 were evaluated. While replacement with Ile showed essentially no effect on rate of cleavage, replacement with Asn resulted in an ~2-fold rate reduction. This effect was not predicted given the differences in the side chains and the reason for this result is not clear. A surprising result was the ~2-fold acceleration in cleavage rate when the P3’ Asn339 was replaced with Gln. Since Gln is larger than Asn by a single methylene group and given that the S3’ site appears unusually large [20], this result suggests the larger Gln may provide a better fit at this site.

Earlier results showing the en bloc replacement of the P4-P3’ residues flanking Arg336 with those of Arg562 yielded an ~100-fold reduction in the rate of cleavage at Arg336 [13]. However, results from the current study show generally modest effects on cleavage following each individual substitution. Additionally, results from the earlier study showed that mutating clusters of prime and non-prime residues separately yielded 16- and 9-fold reductions in cleavage rates, respectfully. Taken together, these observations suggest a synergy of residues with respect to cleavage rate in the presence of the native flanking region sequence.

While residues flanking APC cleavage sites in factor VIIIa influence the rate of catalysis of cleavage ([13] and this study), primary binding between factor VIIIa and APC appear dependent upon interactions with exosites [12]. For example, mutations of the P1 Arg336 and 562 residues to Gln [11] or replacing the P4-P3’ residues flanking Arg336 with those flanking Arg562 [13] yielded variants that effectively competed with wild type factor VIII for cleavage and inactivation by APC. These results parallel earlier observations by Orcutt et al. [23] who showed that mutating P3-P1 residues in prethrombin 2 markedly reduced rates of activation by factor Xa or prothrombinase but did not appreciably affect substrate affinity.

An earlier study replacing the P1 Arg residues at 336 and 562 with non-cleavable Gln residues showed that cleavage of either site in factor VIIIa by APC was independent of the other site [11]. In the procofactor form, A1 and A2 domains are contiguous and this covalent association may directly impact the observed dependence of cleavage events, as we have seen in this study. This effect is reminiscent of events observed for the cleavage of factor Va where proteolysis appears ordered with attack at the Arg506 site in the A2 domain preceding that at Arg306 in the A1 domain [18]. Reductions in the rate of cleavage at Arg506 following mutation of that residue to Gln yields the factor V Leiden phenotype resulting in marked reductions in the rate of cleavage at Arg306 [24]. We speculate that this observed inter-dependence of cleavage in the factor VIII procofactor may derive in part from altered anion-binding exosite interactions based upon earlier work suggesting an APC anion-binding exosite-interactive site contained in and around A1 subunit residues 337-372 [11].

Rate of inactivation of wild type factor VIIIa lags behind rate of cleavage at the Arg336 site by a factor of two ([11, 13] and this report). We attributed this result to a time-dependent process(es) involving a change in conformation following cleavage and/or loss of a function fragment (i. e., the a1 fragment). Interestingly, a few of the P4-P3’ variants tested showed near equivalent rates of cleavage and activity loss indicating that these mutations facilitated the effect(s) leading to cofactor inactivation following proteolysis. These results further suggest the residues directly flanking the scissile bond make direct contributions to a functional intra- and/or inter-subunit interaction in the cofactor.

Thrombin and factor Xa are efficient activators of factor VIII catalyzing three cleavages in the procofactor, of which two occur in the heavy chain (Arg372 and Arg740) and one in the light chain (Arg1689) (see Ref. [4] for review). Proteolysis at Arg372, the rate limiting step in the activation process [25], is essential to activation as this cleavage exposes functional factor IXa interactive sites in the A2 domain [26]. Other coagulation enzymes including factor VIIa [27] and factor XIa [28] have also been demonstrated to activate factor VIII, albeit with relatively lower catalytic efficiencies. While factor VIIIa is cleaved (and inactivated) by APC much more efficiently than the factor VIII substrate [19], APC appears to cleave the Arg372 bond in factor VIII at near similar rates to that observed for cleavage at Arg336 ([13], and this report). These rates appear to be differentially modulated in that mutations that slow the inactivating cleavage at Arg336, e. g. the ~6-fold rate reduction observed for the Met337Gly variant, resulted in little apparent change in cleavage rate at Arg372. The net result of this change was an “activation” of the procofactor that showed the characteristic spike in factor VIIIa activity followed by a decay phase characteristic of the loss of the A2 subunit. Thus, the capacity for alterations in residues flanking this primary cleavage site in APC to markedly affect rates of cofactor inactivation, as well as to potentially direct this inactivating enzyme to activate its substrate, underscores the importance of this region to the catalytic mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pete Lollar and John Healey for the gift of the factor VIII cloning and expression vectors, and Lisa Regan for the 58.12 monoclonal antibody. We also thank Amy Griffiths and Ivan Rydkin for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants HL76213 and HL38199 from the National Institute of Health. F.V. was supported by an American Heart Association Pre-doctoral Fellowship.

The abbreviations used are

- APC

activated protein C

- BHK

baby hamster kidney

- HEPES

N-[2-hydroxyethyl] piperazine-N’-[2-ethanesulfonic acid]

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Toole JJ, Knopf JL, Wozney JM, Sultzman LA, Buecker JL, Pittman DD, Kaufman RJ, Brown E, Shoemaker C, Orr EC, Amphlett GW, Foster B, Coe ML, Kuntson GJ, Fass DN, Hewick RM. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding human antihaemophilic factor. Nature. 1984;312:342–47. doi: 10.1038/312342a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood WI, Capon DJ, Simonsen CC, Eaton DL, Gitschier J, Keyt B, Seeburg PH, Smith DH, Hollingshead P, Wion KL, Delwart E, Tuddenham EGD, Vehar GA, Lawn RM. Expression of active human factor VIII from recombinant DNA clones. Nature. 1984;312:330–37. doi: 10.1038/312330a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vehar GA, Keyt B, Eaton D, Rodriguez H, O’Brien DP, Rotblat F, Oppermann H, Keck R, Wood WI, Harkins RN, Tuddenham EDG, Lawn RM, Capon DJ. Structure of human factor VIII. Nature. 1984;312:337–42. doi: 10.1038/312337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fay PJ. Activation of factor VIII and mechanisms of cofactor action. Blood Rev. 2004;18:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(03)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lollar P, Parker ET. Structural basis for the decreased procoagulant activity of human factor VIII compared to the procine homolog. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:12481–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fay PJ, Haidaris PJ, Smudzin TM. Human factor VIIIa subunit structure. Reconstruction of factor VIIIa from the isolated A1/A3-C1-C2 dimer and A2 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8957–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fay PJ, Beattie TL, Regan LM, O'Brien LM, Kaufman RJ. Model for the factor VIIIa-dependent decay of the intrinsic factor Xase: Role of subunit dissociation and factor IXa-catalyzed proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6027–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapan KA, Fay PJ. Localization of a factor X interactive site in the A1 subunit of factor VIIIa. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2082–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nogami K, Wakabayashi H, Schmidt K, Fay PJ. Altered interactions between the A1 and A2 subunits of factor VIIIa following cleavage of A1 subunit by factor Xa. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1634–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fay PJ, Beattie T, Huggins CF, Regan LM. Factor VIIIa A2 subunit residues 558–565 represent a factor IXa interactive site. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20522–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varfaj F, Neuberg J, Jenkins PV, Wakabayashi H, Fay PJ. Role of P1 residues Arg336 and Arg562 in the activated-Protein-C-catalysed inactivation of Factor VIIIa. Biochem J. 2006;396:355–62. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manithody C, Fay PJ, Rezaie AR. Exosite-dependent regulation of factor VIIIa by activated protein C. Blood. 2003;101:4802–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varfaj F, Wakabayashi H, Fay PJ. Residues surrounding Arg336 and Arg562 contribute to the disparate rates of proteolysis of factor VIIIa catalyzed by activated protein C. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20264–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansong C, Miles SM, Fay PJ. Epitope mapping factor VIII A2 domain by affinity-directed mass spectrometry: residues 497–510 and 584–593 comprise a discontinuous epitope for the monoclonal antibody R8B12. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:842–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins PV, Freas J, Schmidt KM, Zhou Q, Fay PJ. Mutations associated with hemophilia A in the 558–565 loop of the factor VIIIa A2 subunit alter the catalytic activity of the factor Xase complex. Blood. 2002;100:501–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakabayashi H, Freas J, Zhou Q, Fay PJ. Residues 110–126 in the A1 domain of factor VIII contain a Ca2+ binding site required for cofactor activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12677–12684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nogami K, Zhou Q, Wakabayashi H, Fay PJ. Thrombin-catalyzed activation of factor VIII with His substituted for Arg372 at the P1 site. Blood. 2005;105:4362–4368. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalafatis M, Rand MD, Mann KG. The mechanism of inactivation of human factor V and human factor Va by activated protein C. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31869–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fay PJ, Smudzin TM, Walker FJ. Activated protein C-catalyzed inactivation of human factor VIII and factor VIIIa. Identification of cleavage sites and correlation of proteolysis with cofactor activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mather T, Oganessyan V, Hof P, Huber R, Foundling S, Esmon C, Bode W. The 2.8 A crystal structure of Gla-domainless activated protein C. EMBO J. 1996;15:6822–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rezaie AR. Insight into the molecular basis of coagulation proteinase specificity by mutagenesis of the serpin antithrombin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12179–85. doi: 10.1021/bi0261443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezaie AR, Esmon CT. Conversion of glutamic acid 192 to glutamine in activated protein C changes the substrate specificity and increases reactivity toward macromolecular inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19943–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orcutt S, Pietropalo C, Krishnaswamy S. Extended interactions with prothrombinase enforce affinity and specificity for its macromolecular substrate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46191–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalafatis M, Lu D, Bertina RM, Long GL, Mann KG. Biochemical prototype for familial thrombosis. A study combining a functional protein C mutation and factor V Leiden. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:2181–2187. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.12.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newell JL, Fay PJ. Proteolysis at Arg740 facilitates subsequent bond cleavages during thrombin-catalyzed activation of factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25367–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fay PJ, Mastri M, Koszelak ME, Wakabayashi H. Cleavage of factor VIII heavy chain is required for the functional interaction of A2 subunit with factor IXa. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12434–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warren DL, Morrissey JH, Neuenschwander PF. Proteolysis of blood coagulation factor VIII by the factor VIIa-tissue factor complex: generation of an inactive factor VIII cofactor. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6529–36. doi: 10.1021/bi983033o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whelihan MF, Orfeo T, Gissel MT, Mann KG. Coagulation procofactor activation by factor XIa. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1532–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]