Abstract

In geographic atrophy (GA), the non-neovascular end stage of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the macular retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) progressively degenerates. Membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD46) is the only membrane-bound regulator of complement expressed on the human RPE basolateral surface. Based on evidence of the role of complement in AMD, we hypothesized that altered CD46 expression on the RPE would be associated with GA development and/or progression. Here we report the timeline of CD46 protein expression changes across the GA transition zone, relative to control eyes, and relative to events in other chorioretinal layers. Eleven donor eyes (mean age 87.0 ± 4.1 yr) with GA and 5 control eyes (mean age 84.0 ± 8.9 yr) without GA were evaluated. Macular cryosections were stained with PASH for basal deposits, von Kossa for calcium, and for CD46 immunoreactivity. Internal controls for protein expression were provided by an independent basolateral protein, monocarboxylate transporter 3 (MCT3) and an apical protein, ezrin. Within zones defined by 8 different semi-quantitative grades of RPE morphology, we determined the location and intensity of immunoreactivity, outer segment length, and Bruch’s membrane calcification. Differences between GA and control eyes and between milder and more severe RPE stages in GA eyes were assessed statistically. Increasing grades of RPE degeneration were associated with progressive loss of polarity and loss of intensity of staining of CD46, beginning with the stages that are considered normal aging (grades 0–1). Those GA stages with affected CD46 immunoreactivity exhibited basal laminar deposit, still-normal photoreceptors, and concomitant changes in control protein expression. Activated or anteriorly migrated RPE (grades 2–3) exhibited greatly diminished CD46. Changes in RPE CD46 expression occur early in GA, before there is evidence of morphological RPE change. At later stages of degeneration, CD46 alterations occur within a context of altered RPE polarity. These changes precede degeneration of the overlying retina and suggest that therapeutic interventions be targeted to the RPE.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, geographic atrophy, complement, CD46, inflammation, immunohistochemistry, histopathology, human

1. Introduction

1.1.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) affects 11 million elderly individuals in the United States (Congdon et al., 2004). AMD involves four layers of the chorioretinal complex (from outer to inner): 1) the choriocapillaris; 2) Bruch’s membrane (BrM), the inner wall of the choroidal vasculature and site of the hallmark extracellular lesions of AMD (drusen and basal deposits (Green and Enger, 1993; Sarks, 1976)); 3) the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a polarized monolayer that maintains photoreceptor health; and 4) the photoreceptors, which are ultimately affected in AMD. Choroidal neovascularization, an invasion of choriocapillaries through BrM (Grossniklaus and Green, 2004), is a sight-threatening complication in ~15% of AMD patients, treatable with intraocular injections of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors (Ciulla and Rosenfeld, 2009; Rich et al., 2006). In contrast, geographic atrophy (GA), manifesting as sharply circumscribed areas of RPE cell death across the macula, preceded by soft drusen and RPE detachments (Klein et al., 2008; Roquet et al., 2004), is a slow and currently untreatable loss of vision.

1.2.

Now that treating choroidal neovascularization is lowering the burden of vision loss from that complication of AMD, GA is receiving attention as ophthalmology’s next major challenge for new therapeutic approaches (Meleth et al., 2011). Clinical trials involving immunomodulatory, anti-oxidant, retinoid-binding, and cyto-protective agents are underway. Quantifying the rate or extent of the slow outward expansion of atrophy is recognized as appropriate for tracking GA progression and monitoring efficacy of new treatments (Csaky et al., 2008; Sunness et al., 2007a) (Csaky et al., 2008; Sunness et al., 2007b). Further, contemporary clinical imaging techniques reveal the transition zone between unaffected and atrophic RPE in unprecedented detail (Bearelly et al., 2009; Brar et al., 2009a; Fleckenstein et al., 2008; Fleckenstein et al., 2010). Because cells at this critical transition zone between normal and atrophic retina are likely to die and in fact may be fated for death regardless of intervention, an understanding of the molecular changes in this region is important for validating GA enlargement as a clinical endpoint. Histopathologic characterizations of this GA transition are limited (Curcio et al., 1996; Guidry et al., 2002; McLeod et al., 2009; Sarks et al., 1988), showing RPE cells of irregular shape and pigmentation, involuted choriocapillaries, loss of photoreceptors (especially rods), and, up-regulation of the intermediate filament protein vimentin in reactive, overtly altered RPE (Guidry et al., 2002). These changes are a classic RPE stress response, but the events leading to these alterations are unknown, although toxic Alu RNA has been recently implicated (Kaneko et al., 2011). Initial changes occuring within RPE are thought to be central to AMD pathogenesis (Hogan, 1972).

1.3.

The complement system clearly is involved in the pathogenesis of AMD, with many activated fragments of the complement cascade detectable in drusen, (Anderson et al., 2002; Crabb et al., 2002; Hageman et al., 2001; Mullins et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2010b) and alterations in complement factors, both pro-inflammatory(Jakobsdottir et al., 2008; McKay et al., 2009) and regulatory,(Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman, 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Jakobsdottir et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2005; Zareparsi et al., 2005) associated with disease risk. Host tissue is protected from complement by both fluid phase and membrane-bound regulators of complement activation (RCA). The former, specifically factor H, have been most widely linked to AMD risk.(Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman, 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005; Zareparsi et al., 2005) The membrane-bound RCAs CD46 (also called membrane cofactor protein or MCP), CD55 (also called decay accelerating factor or DAF), and CD59 interfere with complement activation at the critical C3 step (CD46 and CD55) or prevent the actions of the membrane attack complex (CD59).

1.4.

The expression pattern of these membrane-bound RCAs has been established in the eye. Cultured human RPE cells exhibit high expression of CD59, intermediate expression of CD46, and low expression of CD55, though the latter is abundant in choroidal endothelial cells (Yang et al., 2009). Of these 3 RCA, CD46 protein was most abundant in freshly isolated human RPE cells, with CD59 protein minimally detectable and CD55 non-detectable. These latter Western blot findings agree with prior work including ours (McLaughlin et al., 2003; Vogt et al., 2006) showing that CD46 is expressed in a highly polarized fashion on the basolateral surface of the RPE. CD46 is thus the only membrane-bound RCA detected by immunohistochemistry on human RPE.

1.5.

Because of its exquisite localization on the basolateral RPE and its presence as at least the most abundant, if not only, RCA on the RPE, CD46 offers the opportunity to address several research questions regarding the RPE and GA and thus was the focus of our studies.

1.5.1.

First, we assessed potential role of CD46 in GA by examining the timing of its expression changes relative to disease progression by quantifying CD46 immunoreactivity changes across the transition from normal to GA in human donor eyes, using a semi-quantitative grading system for RPE pathology (Curcio et al., 1998; Guidry et al., 2002; Sarks, 1976; van der Schaft et al., 1992b) revised to incorporate additional intermediate stages.

1.5.2.

Second, because polarity is an essential RPE function, we provided a cellular context for the CD46 changes with additional immunolabeling studies using other polarized proteins: MCT3 (basolateral) and ezrin (apical).

1.5.3.

Third, since the RPE, photoreceptors, and choriocapillaris are a tightly integrated functional unit, we provided a global context for the RPE changes within overall chorioretinal health by assessing photoreceptor outer segment length, abundance of basal laminar deposit, and BrM calcification (Spraul and Grossniklaus, 1997a; van der Schaft et al., 1992a) within vertically oriented strips of adjoining retina and choroid. We find that polarized protein expression and likely CD46-conferred protection is impaired remarkably early in the GA transition.

2. Methods

2.1. Donor eyes

2.1.1.

All research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and IRB approval was obtained prior to initiation. Details of donors are provided in Table 1. Eleven human donor eyes with grossly visible RPE atrophy consistent with GA and without other gross chorioretinal pathology and 5 age-matched control eyes without AMD were provided by the UAB Age Related Maculopathy Histopathology Laboratory. These eyes resulted from screening post-mortem fundus appearance in non-diabetic donor eyes obtained within 6 hr post-mortem. Clinical records were obtained by follow-up with donor families and eye care providers. Globes were fixed in phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde following removal of the anterior segment and stored in 1% paraformaldehyde at 4°C (Vogt et al., 2006). Maculas were photographed using epi- and trans-illumination after removal of the vitreous.

Table 1.

Donor Eyes

| SingleID | Group | Case # | Age (yr) |

Gender | Clinic information | Genotyping results | GA margin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LastExam | Macular Hx | VAcc | Protective allele | Risk allele | |||||||||

| (mo) | C21 | CFB2 | CFH3 | HTRA14 | ARMS25 | ||||||||

| 2004014L | GA | 1 | 81 | F | 1.8 | Dry ARMD | 2 | GC | AA | TC | AA | TG | lobulated |

| 2000012L | 2 | 82 | M | n.a. | n.a. | n.a | GC | TT | CC | AA | TT | smooth | |

| 2004061L | 3 | 83 | F | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | GG | TT | TC | GG | TG | n.d | |

| 2000067L | 4 | 84 | F | n.a | n.a | n.a. | GG | TT | CC | AA | TG | lobulated | |

| 2000020L | 5 | 85 | F | 8.4 | Dry ARMD | 4 | n.a. | AA | CC | AA | GG | smooth | |

| 2005025L | 6 | 88 | F | 41.2 | Other | 3 | GG | TT | TC | AG | TG | smooth | |

| 2002046L | 7 | 89 | M | 33.2 | CNV/ARMD | 5 | GG | AT | TT | AG | TT | lobulated | |

| 2002095L | 8 | 90 | F | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | GG | AA | CC | AA | GG | lobulated | |

| 2000028L | 9 | 91 | F | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | GG | TT | TC | AG | TG | lobulated | |

| 2004053L | 10 | 91 | F | 87.8 | Dry ARMD | 3 | GC | AT | TC | GG | TG | lobulated | |

| 2000051L | 11 | 93 | M | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | GC | TT | CC | AA | TG | no record | |

| 2004008L | Control | 12 | 75 | M | 14.3 | Normal | 1 | GG | TT | CC | GG | GG | n.a. |

| 2002097L | 13 | 85 | F | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | GG | TT | TC | AA | GG | n.a. | |

| 2003107L | 14 | 92 | F | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | GC | AT | CC | AA | GG | n.a. | |

| 2004054L | 15 | 92 | M | n.a. | n.a | n.a. | GG | TT | TC | GG | GG | n.a. | |

| 2002091R | 16 | 94 | F | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | GG | TT | TC | AG | TG | n.a. | |

All donors were Caucasian. n.d., not determinable from photographs; n.a., not applicable/available.

VAcc, corrected visual acuity; 1=20/20 or better; 2=20/25 − 20/40; 3= 20/50 − 20/200; 4=20/300 − 20/1600; 5= hand movement – light perception.

Complement component 2, SNP rs 9332739, Protective allele C is bold and italicized.

Complement factor B, SNP rs 4151667, Protective allele A is bold and italicized.

Complement factor H, SNP rs1061170 (Y402H). Risk allele C is underlined.

HtrA serine peptidase 1, SNP, rs11200638 (−625G/A). Risk allele A is underlined.

ARSM2, SNP rs 10490924 (A69S). Risk allele T is underlined.

2.2. Tissue preparation, sectioning, and staining

2.2.1.

Rectangular blocks (5 × 8 mm) of fixed tissue containing the macula were cryoprotected, embedded in sucrose OCT, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and sectioned at 10 µM (Vogt et al., 2006). Slides were selected for H&E staining from 3 separate planes through the macula. Selected planes contained at least one transition zone between normal and atrophy, on the temporal side of the macula. Since GA in several eyes included atrophy associated with the peripapillary area, a transition on the nasal side did not exist in those eyes. To permit assessment of overall chorioretinal health, adjacent slides from the 3 planes were stained with periodic acid-Schiff hematoxylin (PASH) for basement membranes and basal laminar deposit and von Kossa for calcium deposition in BrM (kits from Poly Scientific R&D Corp., Bay Shore NY).

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

2.3.1.

Three macular sections per 11 GA and 5 control eyes were analyzed for CD46 and MCT3. One section in each of 5 GA and 2 controls were analyzed for ezrin. Proteins were localized using an alkaline phosphatase Vectastain ABC Kit and a Vector Red Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as described (Vogt et al., 2006). Tissue was incubated overnight at 4°C with either a monoclonal antibody to CD46 (1:100, clone E4.3, Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), a rabbit polyclonal antibody to MCT3 (1:200) (Philp et al., 2003), or a mouse monoclonal to ezrin (1:100, clone 3C12, Abcam)(Kivela et al., 2000). Levamisole was added to minimize background. Slides were dehydrated through ascending alcohols and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Isotype controls with equivalent concentrations of antibody (mouse IgG2a for CD46 (and ezrin) and rabbit IgG for MCT3) were processed concurrently and were negative (not shown).

2.3.2.

A second, smaller section of healthy appearing retina from the same donor was included on the slide with the macular tissue section to serve as an internal positive control for protein labeling. Donor eyes that did not reveal positive staining for either protein in the healthy retinal section were excluded from analysis.

2.4. Microscopic evaluation and imaging

2.4.1.

Zones corresponding to the different RPE morphology grades of the Alabama AMD Grading System (Curcio et al., 1998; Guidry et al., 2002) were independently identified in each tissue section by 2 individuals with expertise in GA and ophthalmic pathology (CA and RWR). Slides were viewed using two research microscopes (BX51, Olympus, Center Valley PA and Eclipse 80i, Nikon, Melville, NY). Sections were read from temporal to nasal (i.e., across the fovea and towards the optic nerve head). To permit determination of zone lengths, zone boundaries were recorded as lengths along BrM in the PASH-stained section using a stepping-motor stage with digital read-out (Ludl, Hawthorne NY) on the Eclipse microscope. Chorioretinal health was assessed by semi-quantitative measures of photoreceptor outer segment length (normal, short, or absent, relative to uninvolved retina on the same section) and basal laminar deposit thickness (none, patchy, <1/2 normal RPE height, >1/2 normal RPE height) for each zone in the PASH-stained sections. To evaluate BrM calcium deposition, the proportion of BrM containing black von Kossa precipitate was expressed as a percent of total BrM length and thickness (< BrM, =BrM, >BrM) for each zone. For CD46, MCT3, and ezrin immunoreactivity, intensity of staining (<normal, normal, >normal) was determined relative to normal RPE on the same slide. Location of staining on individual RPE cells was also recorded. For CD46 and MCT3, location was characterized as “basolateral” or “not basolateral” while for ezrin, location was “apical” or “not apical” with an additional assessment included for the status of delicate apical processes, which could be pulled into an upright position by retinal detachment in some cases or compacted into a layer on the RPE apical surface by others. Information was recorded at the time of microscopy in a custom database (FileMaker, Santa Clara CA).

2.4.2.

Differential interference contrast optics in bright field was used on the Olympus BX51 microscope and digital images captured using an Olympus Qcolor 5 camera (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and Qcapture software (Burnaby, Canada). Images were assembled into a composite without enhancement (Adobe Photoshop CS2, San Jose CA).

2.5. Data analysis and statistics

2.5.1.

The relationship of chorioretinal health and immunoreactivity to RPE pathology grade within and between GA and control eyes was evaluated by pooling semi-quantitative values for each parameter across eyes (1132 graded RPE zones total). Analysis incorporated mixed statistical models to account for clustering of zones within individual eyes.

2.6. SNP genotyping

2.6.1.

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral retina preserved in 1% paraformaldehyde using the Recover All Total Nucleic Acid kit (Ambion Inc., Austin TX) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, tissue was dehydrated in a series of increasing ethanol concentrations ranging from 30% to 100% and then digested with protease at 50°C for 48 hr. DNA concentration (260/280 ratio = 1.8) was determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDropTM 1000 Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Genotyping for complement component 2 (C2, rs9332739), complement factor B (CFB, rs4151667), and age-related maculopathy susceptibility protein 2 (ARMS2, rs10490924) was performed using Taqman single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) Genotyping Assays. Complement factor H (CFH, rs1061170) and HtrA serine peptidase 1 (HTRA1, rs11200638) polymorphisms were determined using Custom Taqman SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Product was amplified using a PTC 200 thermocycler PCR system (MJ Research, Reno, NV).

3. Results

3.1. Patients and eyes, sampling methods, criteria

3.1.1.

Information about study eyes is summarized in Table 1. Eleven GA eyes came from 8 women and 3 men (age 87.0 ± 4.1 yr). Five control eyes came from 3 women and 2 men (age 84.0 ± 8.9 yr). All donors were Caucasian. Available eye health history for 4 of the GA eyes indicated a clinical presentation of AMD at 1.8 to 87.8 months prior to donor death, with visual acuity in these eyes ranging from mildly to severely impaired (Table 1). To characterize the genetic risk profile of each donor, the genotype for several known enhancing and protective genetic states were determined (Table 1). Analysis of risk and protective genotypes for C2, CFB, CFH, HTRA1, and ARMS2 showed only that a greater number of individuals with ARMS2 risk alleles were among GA donors.

3.1.2.

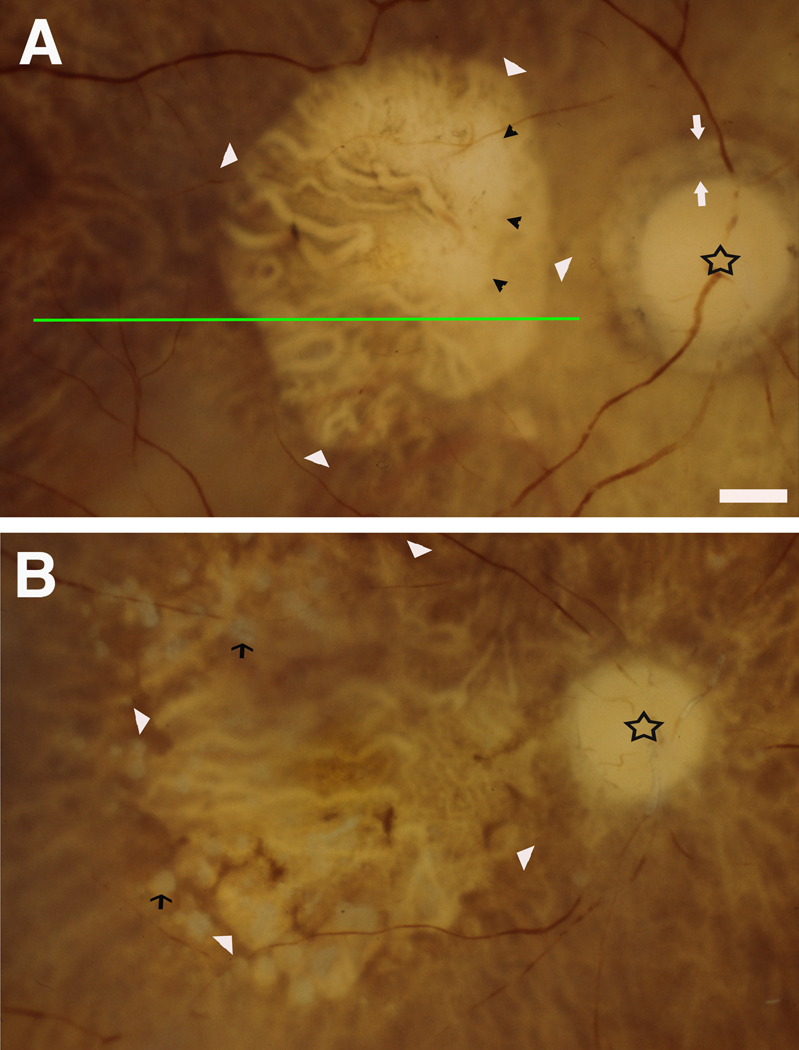

For GA eyes, large areas of RPE atrophy consistent with that diagnosis were evident in the fundi of preserved eyes (Figure 1). The margin between normal and atrophic RPE assumed one of two forms, smooth (Figure 1A) or lobulated (Figure 1B)(Table 1) (Brar et al., 2009b), the latter featuring multiple circular atrophic areas with intervening RPE islands. Some eyes had choroidal atrophy within the area of geographic RPE atrophy (Figure 1A) and drusen were occasionally visible (Figure 1A). An age-related peripapillary chorioretinal degeneration similar to AMD (Curcio et al., 2000; Jonas et al., 1989) surrounded the nerve head completely (n=5) or partly (n=4) in most samples.

Figure 1. Post-mortem fundus appearance in donor eyes with geographic atrophy.

Maculas with anterior segments removed were photographed with trans- and epi-illumination (shown as right eyes). Star indicates optic nerve head. Large retinal vessels are dark red (especially in A). The choroidal circulation, beneath the retina, is best visible in areas where the RPE is atrophic, and the emptied large vessels contrast with the intervening pigmented stroma. Bar = 1 mm. A. Geographic atrophy with a smooth border. White arrowhead, border; white arrow, peripapillary atrophy border; black arrowhead, border of choroidal atrophy. (ID #2000051L, 93 yr, male) B. Geographic atrophy with a lobulated border. White arrowhead, lobulated GA border; black arrows, drusen. (ID# 2000028L, 91 yr, female) Green line demonstrates how histological sections transitioned from unaffected to atrophic areas.

3.2. RPE Staging

3.2.1.

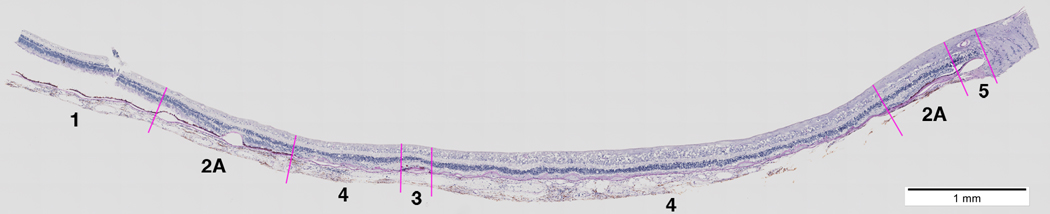

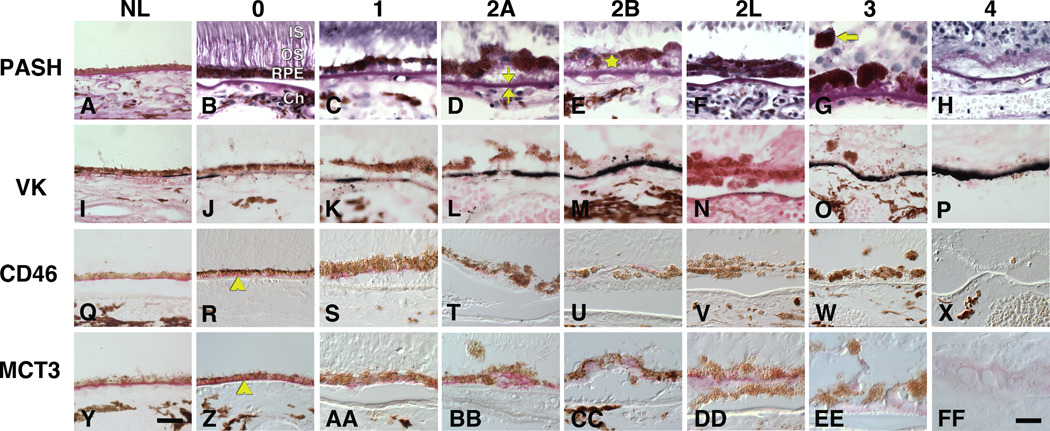

A representative section divided into zones of RPE morphology is shown in Figure 2, and examples of each morphology stage for each stain are shown in Figure 3. Grades 0 (uniform pigmentation and morphology, Figure 3, column 0) and 1 (non-uniform but still epithelioid pigmentation and morphology, Figure 3, column 1) are considered normal aging (Sarks et al., 2007; Sarks, 1976) and will therefore be collectively called normal. Grades 2A (heaping of RPE cells with anterior migration into the sub-retinal space, Figure 3, column 2A), 2B (basal migration into basal deposits, Figure 3, column 2B), and 2L (leaflets of RPE cells, Figure 3, column 2L) indicate an RPE that is attached only partly to BrM or basal deposits. Grade 3 (Figure 3, column 3) reveals anterior migration of pigmented cells across the sub-retinal space through the external limiting membrane and into the neurosensory retina. The fate of these migrating cells is not fully known but melanin and lipofuscin granules can be found interspersed among photoreceptor axons and Müller glial cells in the Henle fiber layer (not shown), suggesting clearance by resident retinal phagocytes. Atrophic areas include Grade 4 (loss of pigmented cells with persisting basal deposits, Figure 3, column 4) and 5 (loss of both pigmented cells and basal laminar deposit, not shown).

Figure 2.

Section of a GA macula demonstrating assignment of RPE pathology zones. Section is stained with periodic acid Schiff-hematoxylin and is located superior to the fovea. Optic nerve and peripapillary terminus of BrM is at the right. Zones of different grades of RPE morphology are indicated. In the evaluation of RPE morphology, sections were read from the uninvolved temporal end (at the left), and new zones were assigned at the first encounter with new pathology.

Figure 3. Grades of RPE change and associated staining patterns in geographic atrophy (for a 2-page spread).

The first column shows control eyes. Other columns show different stains at each pathology grade from different GA eyes. Grades of worsening pathology are arranged across rows. Bright field and differential interference contrast microscopy. Bars, 50 µm. Periodic acid Schiff hematoxylin (PASH). A. Control, grade 0. B. Grade 0, normal RPE morphology. IS, inner segments of photoreceptors, OS, outer segments of photoreceptors; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; Ch, choroid. C. Grade 1, non-uniform RPE, patches of basal deposits. D. Grade 2A, heaped and sloughed RPE, BrM (bracketed) with basal laminar deposit on inner aspect. E. Grade 2B, RPE cellular material shed into basal deposits (star). F. Grade 2L, RPE forms 2 leaflets. G. RPE (arrow) invading neurosensory retina. H. Grade 4, RPE or photoreceptors absent, deposits present. Visible retinal cells are in the inner nuclear layer. Von Kossa stain for calcium (VK, black) reveals compacted laminae within BrM (I-M) and globular particulates within BrM (N), cells (I, M) or basal deposits (M). Q, R. CD46 immunoreactivity (red) localizes to the RPE basolateral aspect (arrowhead). S, T, U. CD46 immunoreactivity is lighter and not limited to the basolateral aspect. V, W, X. CD46 immunoreactivity is undetectable. Y, Z. MCT3 immunoreactivity (red) localizes to the RPE basolateral aspect (arrowhead). AA, BB, CC. MCT3 immunoreactivity is lighter and not limited to the basolateral aspect. DD. MCT3 immunoreactivity is largely, but not exclusively localized to the basolateral aspect of the inner (upper) leaflet of RPE cells. None is present in the outer (lower) leaflet. EE, FF. Pale MCT3 immunoreactivity is present in RPE and in basal deposits (bracketed by carets in CC), the latter persisting after cells disappeared.

3.3. RPE Status and Chorioretinal Health

3.3.1.

The photoreceptors, RPE, and BrM form a highly integrated physiological unit. We evaluated the characteristics of the photoreceptor outer segments and BrM in relation to the adjacent zones of RPE change. A total of 1132 RPE zones were characterized, summarized in Table 2. Control eyes contained mainly long zones of grade 0 and 1, with shorter zones of grades 4 and 5, the latter found exclusively in the peripapillary region. In GA eyes, zones of grade 0 and 1 were shorter than in control eyes, with the addition of numerous short zones of grades 2 to 3. In most eyes, zones at the uninvolved temporal end of sections were rated as grades 0 and 1 while the higher grades were located next to the macular atrophic area. Grades 2A and 2L were on average similar in length, and grade 2B was shorter (Table 2). Grades 2B and 2L were always closer to the atrophic area than 2A. In eyes with lobulated GA margins, the small RPE islands between atrophic areas were exclusively grades 2A, 2B, 2L, or 3. The transition from normal to atrophic RPE typically included 1 to 3 zones of varying grades. Of 166 transitions from 0/1 (normal) to 4/5 (atrophic) observed in GA eyes, 24 (14.5%) passed directly from normal to atrophic, 97 (58.4%) included one intervening zone of grades 2 to 3 (median length, 1.188 mm), and 45 (27.1%) included 2 or more zones of grades 2 to 3 (median length, 2.371 mm).

Table 2.

Zones of RPE morphology

| RPE Grade | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA | 0 | 1 | 2A | 2B | 2L | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| # zones | 75 | 180 | 185 | 22 | 88 | 107 | 193 | 73 |

| % of total zones | 8.1% | 19.5% | 20.0% | 2.4% | 9.5% | 11.6% | 20.9% | 7.9% |

| Mean length, mm | 1.783 | 1.376 | 1.238 | 0.825 | 1.262 | 0.731 | 1.238 | 1.284 |

| Maximum length, mm | 4.206 | 4.479 | 4.622 | 4.473 | 4.334 | 3.771 | 4.838 | 4.334 |

| % of total length analyzed | 11.6% | 21.5% | 19.9% | 1.6% | 9.7% | 6.8% | 20.8% | 8.1% |

| Control | 0 | 1 | 2A | 2B | 2L | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| # zones | 53 | 31 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 8 |

| % of total zones | 39.3% | 23.0% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.7% | 24.4% | 5.9% |

| Mean length, mm | 5.420 | 1.131 | 0.330 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.549 | 0.305 | 0.231 |

| Maximum length, mm | 8.080 | 6.453 | 0.626 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.549 | 0.766 | 0.360 |

| % of total length analyzed | 85.0% | 10.4% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 3.0% | 0.5% |

Legend: RPE, retinal pigment epithelium

3.3.2.

Photoreceptor outer segments (OS) shorten early in the course of all degenerations and injuries affecting these cells (Ripps, 1982). We characterized the length of the OS overlying each RPE zone as either normal (Figure 2B), shortened (Figure 2C), or absent (Figure 2G). In control eyes the OS were absent only adjacent to peripapillary RPE atrophy. In GA eyes, the OS were absent in many zones of grade 2A and higher. Significant changes in OS length were found as RPE atrophy progressed from grades 0 to 5 but not in the early transition between 0 and 1 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Chorioretinal health in relation to RPE grade

| Feature | Group | Pattern | RPE Grade | Within group P value | Between group P value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2A | 2B | 2L | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | Grades 0–5 | Grades 0–1 | Grades 0–5 | Grades 0–1 | |||

| Outer Segments | GA | Absent | 0 | 5 | 24 | 4 | 15 | 33 | 49 | 20 | 150 | <0.0001 | 0.2603 | <0.0001 | 0.1363 |

| Short | 1 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 35 | ||||||

| Normal | 12 | 27 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 51 | ||||||

| Total | 13 | 38 | 44 | 9 | 22 | 39 | 51 | 20 | 236 | ||||||

| Control | Absent | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 7 | <0.0001 | 0.2234 | |||

| Short | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | ||||||

| Normal | 20 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | ||||||

| Total | 21 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 44 | ||||||

| BlamD | GA | None | 11 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 42 | <0.0001 | 0.0059 | <0.0001 | 0.0088 |

| Patchy | 2 | 15 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 3 | 15 | 3 | 67 | ||||||

| <1/2 | 0 | 10 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 20 | 23 | 1 | 77 | ||||||

| >1/2 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 8 | 0 | 43 | ||||||

| Total | 13 | 38 | 44 | 9 | 22 | 39 | 48 | 16 | 229 | ||||||

| Control | None | 12 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 23 | 0.2309 | 0.3606 | |||

| Patchy | 9 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 17 | ||||||

| <1/2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||||||

| >1/2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Total | 21 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 43 | ||||||

| Calcification (%BrM Length) |

GA | Mean% | 36 | 43 | 50 | 16 | 16 | 64 | 60 | 68 | <0.0001 | 0.49 | 0.4814 | 0.0254 | |

| SD | 35 | 38 | 39 | 28 | 23 | 38 | 38 | 32 | |||||||

| Total | 20 | 75 | 85 | 13 | 23 | 40 | 75 | 39 | 370 | ||||||

| Control | Mean % | 13 | 35 | 40 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 42 | 20 | 0.2323 | 0.05 | ||||

| SD | 23 | 37 | 14 | 0 | ---- | 0 | 18 | 0 | |||||||

| Total | 18 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 42 | ||||||

| P value | 0.0254 | 0.4814 | 0.7141 | ---- | 0.5387 | ---- | 0.2977 | 0.0461 | |||||||

| Calcification (Relative to BrM Thickness) |

GA | <BrM | 12 | 42 | 37 25 | 7 | 18 | 19 | 31 | 16 | 182 | 0.0088 | 0.2603 | 0.0079 | 0.1581 |

| =BrM | 7 | 21 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 19 | 13 | 100 | ||||||

| >BrM | 0 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 26 | 10 | 75 | |||||||

| Total | 19 | 72 | 78 | 10 | 23 | 40 | 76 | 39 | 357 | ||||||

| Control | <BrM | 15 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 34 | 0.3719 | 0.5235 | |||

| =BrM | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | ||||||

| >BrM | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||||

| Total | 17 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 41 | ||||||

Legend: RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; GA, geographic atrophy; BlamD, basal laminar deposit; BrM, Bruch's membrane

“Total” refers to total number of observations in each grade.

Note: see Methods for description of grades. <1/2, >1/2 is reference to the typical height of normal RPE.

3.3.3.

Basal laminar deposit (BlamD) is extracellular basement membrane material formed by the RPE, the abundance of which is associated with AMD severity (Sarks et al., 2007; Spraul and Grossniklaus, 1997a). We characterized the presence of BlamD as patchy (Figure 2C), thin continuous (Figure 2E), or thick continuous (Figure 2G). In control eyes BlamD was minimal and almost exclusively patchy. In GA eyes BlamD was significantly more prominent early in the progression between RPE grades 0 and 1 (Table 3).

3.3.4.

Calcification of BrM is associated with risk for choroidal neovascularization (Spraul and Grossniklaus, 1997b). We assessed the degree of calcification of BrM within each RPE zone in von Kossa-stained sections. The percentage of BrM length and the proportion of BrM thickness stained, characterized as less than full thickness (<BrM, Figure 2K) or greater than full thickness (>BrM, Figure 2M), were recorded. In control eyes, BrM calcification was minimal except in the peripapillary region and showed no relationship to RPE grade (Table 3). In GA eyes, calcification of BrM, both in terms of length and thickness, increased with RPE grade, with significant differences among grades 0 and 5 but not between 0 and 1 (Table 3).

3.4.

In summary, all three laminar health indices (photoreceptor outer segment length, BlamD, and BrM calcification) worsened with advancing RPE morphology grade. The index signaling the earliest difference between GA and control eyes and between grades 0 and 1 in GA eyes was BlamD.

3.5. CD46 immunoreactivity: intensity and localization

3.5.1.

CD46 is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on all nucleated cells with four commonly expressed isoforms produced by alternative splicing of its gene. CD46 contains four extracellular short consensus repeats, a transmembrane region, and one of two possible alternatively spliced cytoplasmic tails, both of which contain signalling motifs that mediate distinct cellular functions. CD46 is the only ubiquitously expressed cofactor for the Factor I mediated cleavage of C3b and C4b (Reviewed in (Cardone et al., 2011)).

3.5.2.

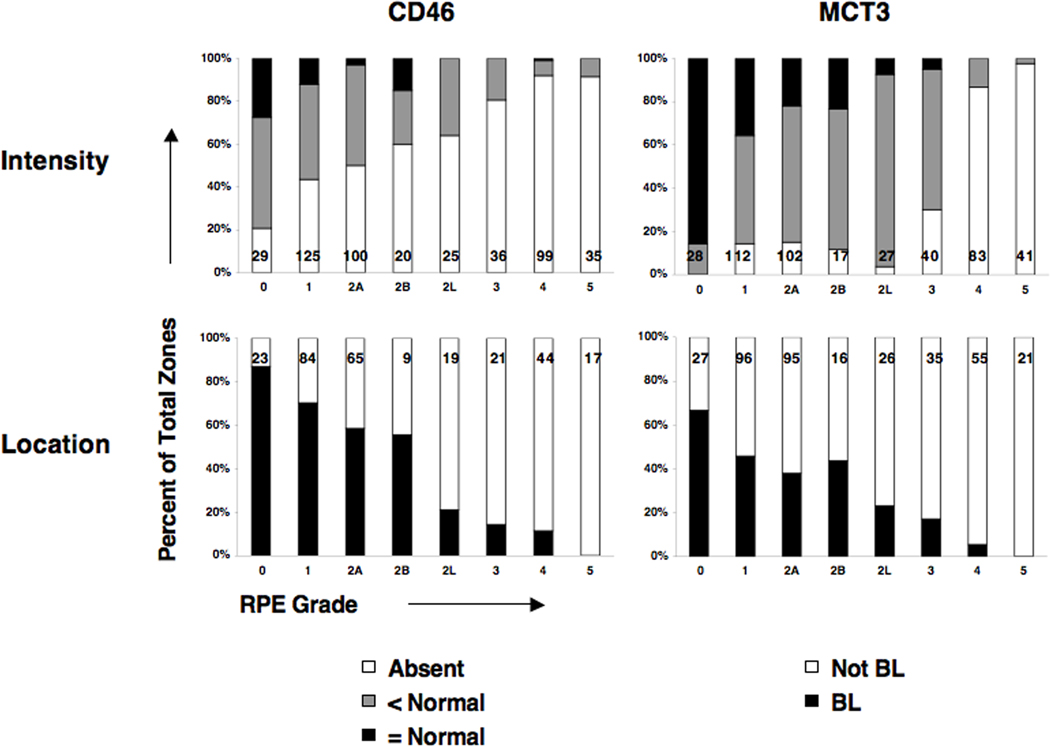

CD46 was readily recognized by the specific and exclusively basolateral location of red reaction product in grade 0 zones of control and GA eyes (Figure 3R) (Vogt et al., 2006). With increasing severity of RPE change, immunoreactivity became less intense (Figure 3S–W). Little CD46 was visible in zones at grade 2L and higher. Further, the location of immunoreactivity departed from basolateral restriction at early grades of RPE change, becoming diffuse and non-polarized (Figure 3T–V). Statistical analysis of CD46 immunoreactivity associated with different RPE grades of GA or control eyes, and between the healthier RPE grades (0, 1) of both groups is provided in Table 4. Alteration from normal in intensity and location were significantly associated with increasing severity of RPE grade in GA, with borderline significant differences between CD46 intensities at grades 0 and 1. Graphical analysis (Figure 4) shows the reduction in CD46 staining intensity and basolateral localization with the progression of RPE alteration across GA lesions.

Table 4.

Association of CD46 and MCT3 staining features with RPE grade

| Feature | Group | Pattern | RPE Grade | Within group P value | Between group P value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2A | 2B | 2L | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | Grades 0–5 | Grades 0–1 | Grades 0–5 | Grades 0–1 | |||

| CD46 Intensity |

GA | Absent | 6 | 54 | 50 | 12 | 16 | 29 | 91 | 32 | 290 | <0.0001 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | 0.07 |

| <Normal | 15 | 55 | 47 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 148 | ||||||

| =Normal | 8 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 30 | ||||||

| >Normal | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Total | 29 | 125 | 100 | 20 | 25 | 36 | 99 | 35 | 469 | ||||||

| Control | Absent | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 15 | 0.0061 | 0.757 | |||

| <Normal | 14 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 26 | ||||||

| =Normal | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | ||||||

| Total | 20 | 16 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 48 | ||||||

| CD46 Location |

GA | BL | 20 | 59 | 38 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 134 | <0.0001 | 0.11 | <0.0001 | 0.05 |

| Not BL | 3 | 25 | 27 | 4 | 15 | 18 | 39 | 17 | 148 | ||||||

| Total | 23 | 84 | 65 | 9 | 19 | 21 | 44 | 17 | 282 | ||||||

| Control | BL | 16 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 0.0012 | 0.26 | |||

| Not BL | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 13 | ||||||

| Total | 18 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 40 | ||||||

| MCT3 Intensity |

GA | Absent | 0 | 16 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 72 | 40 | 158 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| <Normal | 4 | 56 | 63 | 11 | 24 | 26 | 11 | 1 | 196 | ||||||

| =Normal | 24 | 40 | 22 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 94 | ||||||

| >Normal | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||||

| Total | 28 | 112 | 102 | 17 | 27 | 40 | 83 | 41 | 450 | ||||||

| Control | Absent | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 10 | <0.0001 | 0.1 | |||

| <Normal | 7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 19 | ||||||

| =Normal | 24 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 | ||||||

| Total | 31 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 65 | ||||||

| MCT3 Location |

GA | BL | 18 | 44 | 36 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 120 | <0.0001 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | 0.02 |

| Not BL | 9 | 52 | 59 | 9 | 20 | 29 | 52 | 21 | 251 | ||||||

| Total | 27 | 96 | 95 | 16 | 26 | 35 | 55 | 21 | 371 | ||||||

| Control | BL | 11 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0.1871 | 0.2 | |||

| Not BL | 20 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 45 | ||||||

| Total | 31 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 60 | ||||||

Note: see Methods for description of grades. BL, basolateral.

There were no instances of staining that were > Normal in the control eyes.

“Total” refers to total number of observati in each grade.

Figure 4. Protein expression by RPE grade in GA eyes.

Data for intensity and location of immunoreactivity are displayed as a percentage of total zones rated (1,132) pooled across all GA eyes (Table 2). The total number of zones per grade is shown at the base of each grade’s bar. Normal is referenced to the staining characteristics of RPE at grade 0 in periphery of GA eyes. CD46 and MCT3 immunoreactivity diminishes in intensity and becomes progressively less polarized, in association with worsening RPE morphology. MCT3 immunoreactivity is apparent at higher grades than CD46. Basolateral indicates that staining is confined to the basolateral surface. The differences between grades 0 and 1 are significant (see Table 3) Not basolateral indicates that staining was not so confined. Legend: BL, basolateral.

3.6. Analysis of other polarized proteins (MCT3 and ezrin): intensity and location

3.6.1.

To determine if altered CD46 expression is due to global changes in polarized protein expression unrelated to complement, we assessed immunoreactivity for MCT3, a basolaterally expressed transporter, and ezrin, an apically expressed actin-associated protein.

3.6.2.

The MCTs are members of the SLC16A gene family of transporters and several MCT isoforms are expressed in the mammalian eye. MCT3 (Slc16a8) is preferentially expressed at high levels in the differentiated RPE cells where it is polarized to the RPE basolateral membrane (Longbottom et al., 2009; Philp et al., 2001).

3.6.3.

Overall, MCT3 exhibited more intense staining in grade 0 of control and GA eyes (Figure 3Z) than CD46. MCT3 was present diffusely and exclusively on the inner leaflet of grade 2L RPE cells (Figure 3DD). MCT3 was not detected in any grade 3 cells within the neurosensory retina. MCT3 was detected extracellularly (Figure 3BB,CC), even within deposits persisting after complete RPE atrophy (Figure 3FF), consistent with others findings about membrane-bound proteins of basolateral RPE origin (Gouras et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2001). Statistical and graphical analysis of MCT3 immunoreactivity (Table 4, Figure 4) showed that the decline with advancing pathology was consistent with that seen with CD46. At the earliest stages of RPE change within GA eyes, MCT3 intensity differs significantly between grades 0 and 1 while location changes are of borderline significance at that stage.

3.6.4.

The ezrin/ radixin/ moesin (ERM) protein family is part of the cortical cytoskeleton and provides architectural and/or regulatory contribution to epithelial actin cytoskeleton. Ezrin is localized in the long apical microvilli of RPE cells that invest outer segment tips and participate in phagocytosis, serving as an epithelial marker and a morphogenetic agent in development (Bonilha, 2007).

3.6.5.

Ezrin immunoreactivity was decreased in the macula of GA eyes, roughly in relation to worsening RPE pathology (Figure 5). The small sample of eyes available for ezrin staining precludes assessing the stage of change to the same degree possible for CD46 and MCT3. Changes in ezrin localization were consistent with those seen for MCT3, i.e., labeling was not confined to the typical apical domain, only the inner leaflet of stage 2L showed orthotopic staining, and extracellular labeling was detected. Some cells sloughed into the sub-retinal space (2A) exhibited diffusely distributed ezrin immunoreactivity without detectable apical processes.

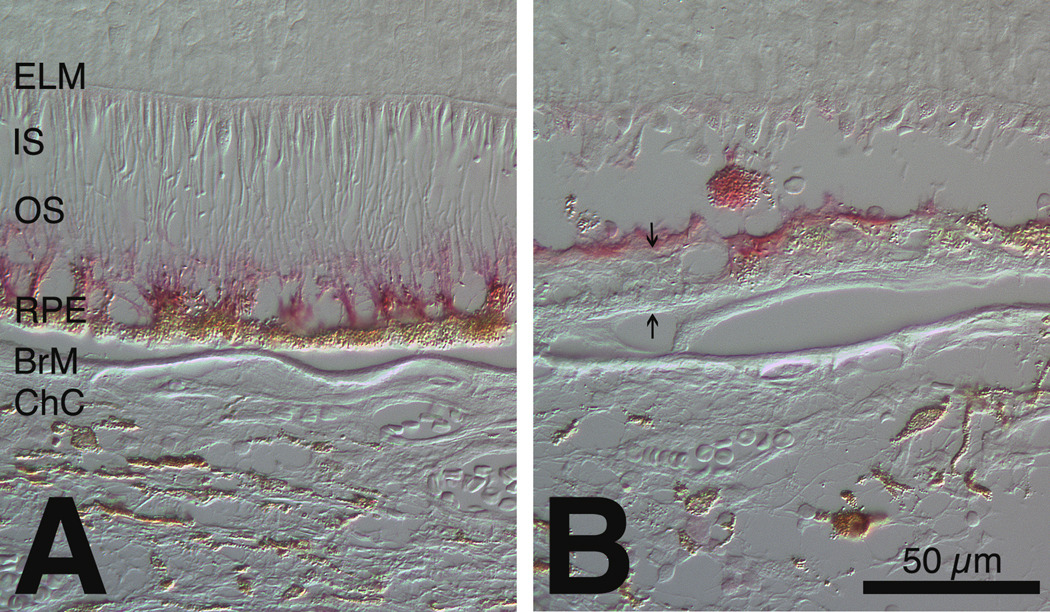

Figure 5. Ezrin localization in unaffected periphery (A) and affected macula (B) of geographic atrophy eye.

Immunoreactivity is red. Differential interference contrast microscopy. A. RPE apical processes are upright and intensely immunoreactive after detachment of neurosensory retina. B. Light extracellular immunoreactivity and a diffusely labeled sloughed RPE cell in a grade 2A area. Arrows delimit BlamD. ELM, external limiting membrane; IS, inner segments; OS, outer segments; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; BrM, Bruch’s membrane; ChC, choriocapillaris.

4. Discussion

4.1.

The current study includes, to our knowledge, the largest group to date of exclusively GA eyes examined with immunohistochemical methods and the first to focus on RPE health and the transition between normal and atrophic cells. We found alterations in RPE expression of complement regulator CD46, at least one other RPE specific basolateral protein (MCT3) and an apical protein (ezrin). Strikingly, these alterations are apparent at the earliest stages of GA (stage 1), prior to frank atrophy or even clinically detectable change. Eyes with GA exhibited less intense CD46 staining at healthier RPE grades (0–1) than control eyes, suggesting altered RPE cell health even in cells with near normal morphology and in advance of pathology in adjacent photoreceptors or BrM. Our results have significance for understanding the role of complement, the status of polarized RPE functions, and the timeline of disease progression across the GA transition.

4.2. Implications of findings for role of complement in AMD

4.2.1.

Despite multiple theories, the specific inciting event(s) leading to RPE degeneration and the development of AMD are unknown. One potential stressor is chronic inflammation, possibly evoked by lipid hydroperoxides on lipoproteins deposited with age in BrM (Curcio et al., 2009; Spaide et al., 2003) or shed cellular debris (Hageman et al., 2001). Complement is continually activated in the serum at a low level, a process known as tick over activation. If not regulated, then this low level activation is amplified and clinically significant levels of activated complement components are created. It is thus possible that a defect in complement regulation by any RCA could result in the chronic inflammation thought involved in AMD pathogenesis. This concept is supported by both genetic and tissue-based studies. A tyrosine-402 to histidine-402 protein polymorphism in the RCA Factor H is associated with a significantly increased AMD risk Edwards, 2005 #3030;Hageman, 2005 #3027;Haines, 2005 #3029;Klein, 2005 #3028]. Associations with other complement component genes have also been found, including factor B, C2, and C3. (Gold et al., 2006) (Maller et al., 2007). Drusen contain complement components C1q, C3, C5, and C5b-9 (Anderson et al., 2002; Crabb et al., 2002; Hageman et al., 2001; Mullins et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2010b).

4.2.2.

Based on the hypothesis that reduced CD46 on the RPE is detrimental to the RPE, we sought to determine if changes in the presence of CD46 on the RPE were associated with early stage AMD. We found alterations in RPE CD46 expression progressively increase as RPE morphology deteriorates in the transition from normal to GA. Of greatest significance, changes in CD46 expression occur even on grade 1 RPE cells, which exhibit minimal morphological alterations. Whether these CD46 changes indicate that a defect in complement protection is an initiating factor in GA or another manifestation of an already dysfunctional RPE remains to be determined. Either of these scenarios could lead to the extracellular complement deposition documented in AMD, as both result in reduced CD46 expression on the RPE. Others have shown that CD46 on the RPE interacts with β−1 integrin, suggesting a role in basement membrane adhesion (McLaughlin et al., 2003). A progressive loss of this interaction could explain the release of RPE cells from BrM in grades 2 and 3. The classic description of complement actions includes nonspecific targeting of cells for phagocytosis, induction of inflammation via anaphylatoxin production, and assembly of the membrane attack complex, a pore forming structure that inserts into cell membranes to disrupt homeostasis (Walport, 2001a, b). However, features of this acute phase reaction, such as an influx of neutrophils and macrophages (at least in large number), and lysis of RPE, were not detectable in our sample, suggesting that complement‘s involvement in GA is not in the “classical” sense, but rather is likely involved in induction of chronic inflammation.

4.3. Implications of findings for RPE and its polarized functions

4.3.1.

We provided the first in situ evidence regarding RPE polarity status in AMD eyes, with the finding that stage-specific loss of CD46 occurs in the setting of decreased expression of two other highly polarized RPE proteins. Part of the outer-blood retinal barrier, the RPE provides essential services to both photoreceptors and choriocapillaris, and like other epithelia, it is structurally and functionally polarized (Strauss, 2005). The RPE polarity program includes mechanisms for directional sorting and delivery of bio-molecules and maintenance of apical and basolateral domain-identity. The latter, in turn, involves the circumferential belt of tight junctions that provide a fence between those two domains and helps organize intracellular secretory, endocytotic, and cytoskeletal pathways (Tanos and Rodriguez-Boulan, 2008). miR-204 and Mir-211 expression are essential for maintaining differentiated properties of the RPE including junctional proteins that maintain trans-epithelial resistance (Wang et al., 2010a). Trans-epithelial transport of lactate from aerobic glycolysis (Wang et al., 1997; Winkler et al., 1997) is facilitated by monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) in apical and basolateral RPE membranes (Philp et al., 2003). MCT3 expression is developmentally regulated, making it a marker for differentiated RPE cells, and loss of MCT3 occurs rapidly in mechanically wounded monolayers of human fetal RPE. (Gallagher-Colombo et al., 2010). Ezrin is present throughout the entire length of RPE microvilli, which play essential roles in phagocytosis and retinoid processing (Bonilha et al., 2004; Steinberg et al., 1977). As apical processes have been observed in early AMD eyes (Curcio et al., 1996), their loss in GA is a novel observation, warranting additional samples for more detailed characterization.

4.3.2.

We propose that the observed changes in CD46, MCT3, and ezrin expression collectively serve as bellwethers for other key RPE functions that may also be impaired in AMD eyes. These include orchestration of chemokine release (Shi et al., 2008), secretion of angiogenic VEGF and angiostatic PEDF (Sonoda et al., 2010), and expression of junctional complexes (Economopoulou et al., 2009), all of which are dramatically less efficient in non-polarized cells (Sonoda et al., 2010).

4.4. Implications of approach for time line of GA progression

4.4.1.

Our RPE-based grading system exploits the layered organization of the retina and choroid, using spatial localization as a surrogate for time of disease progression. We refined existing histopathologic stagings of AMD severity (Curcio et al., 1998; Curcio et al., 2000; Guidry et al., 2002; Sarks, 1976; van der Schaft et al., 1992b) to include several RPE morphologies (grades 2A, 2B, 2L) preceding cell death (grade 4). Grades were based on a characteristic RPE stress response described in multiple conditions (Anderson et al., 2010; Capon et al., 1989; Hahn, 2004; Hilton, 1974; Kuntz et al., 1996; Lopez et al., 1995; Zhao et al., 2011). These RPE grades do not represent snapshots of a linear process in time. Early reactive Grade 2A cells are plausible direct precursors of grade 3 cells, but grades 2B and 2L appear to represent alternative routes to RPE death. Of note, in clinical descriptions of the GA transition zone using spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT), the hyper-reflective band commonly interpreted as RPE-BrM shows irregularities, elevations, double layers, and associated clumps in the subretinal space and neurosensory retina (Fleckenstein et al., 2008), remarkably similar to our grades 2–3. Further, over time these areas lose reflectivity and eventually fade to become newly formed atrophy (Fleckenstein et al., 2010), consistent with our histological interpretations.

4.4.2.

We found that reduced CD46 and MCT3 immunoreactivity and basal deposit accumulation occurred early in GA disease process, when RPE morphology was minimally affected at grade 1, whereas photoreceptor degeneration was not reliably detected until the RPE was more seriously affected at grade 2A. Although patchy BlamD is considered normal aging (Bressler et al., 2006), it begins a continuum that ends with the abundant BlamD associated with AMD (Spraul and Grossniklaus, 1997a). These changes should be interpreted in the context of normal aging, as, rod photoreceptors in the macula die slowly throughout adulthood and RPE numbers remain stable (Curcio et al., 1993; Del Priore et al., 2002). In contrast, in GA loss of RPE polarity and deposition of BlamD together suggest that RPE degeneration precedes that of the photoreceptors, at least as detectable by light microscopy. Further, current evidence suggests that RPE dysfunction also precedes secondary choriocapillaris loss in GA (McLeod et al., 2009). This implies that therapies and interventions to save outer retinal functions are best directed at the RPE.

4.5.

In summary, we have shown that RPE expression of the complement regulator CD46 at the very earliest stages of AMD. This alteration consists of a loss of intensity of staining as well as alterations in the polarized location of staining, the latter associated with more advanced stages of RPE degeneration. These changes parallel those seen in other polarized proteins not associated with complement (MCT3 and ezrin). The current study is limited by its use of immunohistochemical methods to detect protein presence and semi-quantify protein levels as well as by a limitation in the number of stains that could be performed due to tissue availability. Thus a characterization of whether alterations in complement activation status or fragment deposition were present concurrent with regulator alteration was not performed. Nonetheless, the findings presented are intriguing in their demonstrating RPE protein alterations at the earliest stages of GA, before clinically apparent changes are evident.

Highlights.

We examine expression of complement regulator CD46 on the RPE in geographic atrophy

CD46 expression is compared to control polarized proteins MCT3 and ezrin

CD46 expression is altered at the earliest stage of geographic atrophy

This alteration occurs before clinically detectable changes are evident

Acknowledgments

We thank the Alabama Eye Bank for timely retrieval of donor eyes..

Support: International Retinal Research Foundation (no grant #)(SDV, CAC, RWR); EyeSight Foundation of Alabama grant FY2006-07-31 (SDV, RWR); NIH grant EY06109 (CAC); NIH grant EY012042 (NJP); and unrestricted funds to the Department of Ophthalmology from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., and EyeSight Foundation of Alabama. Dr. Read is a Research to Prevent Blindness Physician-Scientist.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson DH, Mullins RF, Hageman GS, Johnson LV. A role for local inflammation in the formation of drusen in the aging eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:411–431. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Radeke MJ, Gallo NB, Chapin EA, Johnson PT, Curletti CR, Hancox LS, Hu J, Ebright JN, Malek G. The pivotal role of the complement system in aging and age-related macular degeneration: Hypothesis re-visited✩. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2010;29:95–112. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearelly S, Chau FY, Koreishi A, Stinnett SS, Izatt JA, Toth CA. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging of geographic atrophy margins. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1762–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha VL. Focus on molecules: ezrin. Exp. Eye Res. 2007;84:613–614. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha VL, Bhattacharya SK, West KA, Crabb JS, Sun J, Rayborn ME, Nawrot M, Saari JC, Crabb JW. Support for a proposed retinoid-processing protein complex in apical retinal pigment epithelium. Exp. Eye Res. 2004;79:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brar M, Kozak I, Cheng L, Bartsch DU, Yuson R, Nigam N, Oster SF, Mojana F, Freeman WR. Correlation between spectral-domain optical coherence tomography and fundus autofluorescence at the margins of geographic atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009a;148:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brar M, Kozak I, Cheng L, Bartsch DU, Yuson R, Nigam N, Oster SF, Mojana F, Freeman WR. Correlation between spectral-domain optical coherence tomography and fundus autofluorescence at the margins of geographic atrophy. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009b;148:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler SB, Bressler NM, Sarks SH, Sarks JP. Age-related macular degeneration: nonneovascular early AMD, intermediate AMD, and geographic atrophy. In: Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. Mosby: 2006. pp. 1041–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Capon MR, Marshall J, Krafft JI, Alexander RA, Hiscott PS, Bird AC. Sorsby's fundus dystrophy. A light and electron microscopic study. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1769–1777. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardone J, Le Friec G, Kemper C. CD46 in innate and adaptive immunity: an update. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2011;164:301–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciulla TA, Rosenfeld PJ. Antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2009;20:158–165. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32832d25b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon N, O'Colmain B, Klaver CC, Klein R, Munoz B, Friedman DS, Kempen J, Taylor HR, Mitchell P. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb JW, Miyagi M, Gu X, Shadrach K, West KA, Sakaguchi H, Kamei M, Hasan A, Yan L, Rayborn ME, Salomon RG, Hollyfield JG. Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14682–14687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222551899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csaky KG, Richman EA, Ferris FL., 3rd Report from the NEI/FDA Ophthalmic Clinical Trial Design and Endpoints Symposium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:479–489. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang J-D, Rudolf M. Aging, age-related macular degeneration, and the Response-to-Retention of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. Prog Ret Eye Res. 2009;28:393–422. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio CA, Medeiros NE, Millican CL. Photoreceptor loss in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1236–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio CA, Medeiros NE, Millican CL. The Alabama Age-Related Macular Degeneration Grading System for donor eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1085–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio CA, Millican CL, Allen KA, Kalina RE. Aging of the human photoreceptor mosaic: evidence for selective vulnerability of rods in central retina. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1993;34:3278–3296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio CA, Saunders PL, Younger PW, Malek G. Peripapillary chorioretinal atrophy: Bruch's membrane changes and photoreceptor loss. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:334–343. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Priore LV, Kuo YH, Tezel TH. Age-related changes in human RPE cell density and apoptosis proportion in situ. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2002;43:3312–3318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economopoulou M, Hammer J, Wang F, Fariss R, Maminishkis A, Miller SS. Expression, localization, and function of junctional adhesion molecule-C (JAM-C) in human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1454–1463. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AO, Ritter R, 3rd, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1110189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein M, Charbel Issa P, Helb HM, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Finger RP, Scholl HP, Loeffler KU, Holz FG. High-resolution spectral domain-OCT imaging in geographic atrophy associated with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4137–4144. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Adrion C, Kramer I, Eter N, Helb HM, Brinkmann CK, Charbel Issa P, Mansmann U, Holz FG. Tracking Progression using Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography in Geographic Atrophy due to Age-related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Colombo S, Maminishkis A, Tate S, Grunwald GB, Philp NJ. Modulation of MCT3 expression during wound healing of the retinal pigment epithelium. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2010;51:5343–5350. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold B, Merriam JE, Zernant J, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Gehrs K, Cramer K, Neel J, Bergeron J, Barile GR, Smith RT, Hageman GS, Dean M, Allikmets R. Variation in factor B (BF) and complement component 2 (C2) genes is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:458–462. doi: 10.1038/ng1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras P, Braun K, Ivert L, Neuringer M, Mattison JA. Bestrophin detected in the basal membrane of the retinal epithelium and drusen of monkeys with drusenoid maculopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:1051–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WR, Enger C. Age-related macular degeneration histopathologic studies. The 1992 Lorenz E. Zimmerman Lecture. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1519–1535. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus HE, Green WR. Choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry C, Medeiros NE, Curcio CA. Phenotypic variation of retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman GS. From The Cover: A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:7227–7232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501536102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman GS, Luthert PJ, Victor Chong NH, Johnson LV, Anderson DH, Mullins RF. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch's membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:705–732. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn P. Disruption of ceruloplasmin and hephaestin in mice causes retinal iron overload and retinal degeneration with features of age-related macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:13850–13855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Olson LM, Gallins P, Spencer KL, Kwan SY, Noureddine M, Gilbert JR, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Agarwal A, Postel EA, Pericak-Vance MA. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:419–421. doi: 10.1126/science.1110359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton GF. Subretinal pigment migration. Effects of cryosurgical retinal reattachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;91:445–450. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1974.03900060459006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan MJ. Role of the retinal pigment epithelium in macular disease. Trans. Am. Acad. Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. 1972;76:64–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsdottir J, Conley YP, Weeks DE, Ferrell RE, Gorin MB. C2 and CFB genes in age-related maculopathy and joint action with CFH and LOC387715 genes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LV, Leitner WP, Staples MK, Anderson DH. Complement activation and inflammatory processes in Drusen formation and age related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:887–896. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas JB, Nguyen XN, Gusek GC, Naumann GOH. Parapapillary chorioretinal atrophy in normal and glaucoma eyes. I. Morphometric data. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989;30:908–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko H, Dridi S, Tarallo V, Gelfand BD, Fowler BJ, Cho WG, Kleinman ME, Ponicsan SL, Hauswirth WW, Chiodo VA, Kariko K, Yoo JW, Lee DK, Hadziahmetovic M, Song Y, Misra S, Chaudhuri G, Buaas FW, Braun RE, Hinton DR, Zhang Q, Grossniklaus HE, Provis JM, Madigan MC, Milam AH, Justice NL, Albuquerque RJ, Blandford AD, Bogdanovich S, Hirano Y, Witta J, Fuchs E, Littman DR, Ambati BK, Rudin CM, Chong MM, Provost P, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA, Dunaief JL, Baffi JZ, Ambati J. DICER1 deficit induces Alu RNA toxicity in age-related macular degeneration. Nature. 2011;471:325–330. doi: 10.1038/nature09830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivela T, Jaaskelainen J, Vaheri A, Carpen O. Ezrin, a membrane-organizing protein, as a polarization marker of the retinal pigment epithelium in vertebrates. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:217–223. doi: 10.1007/s004410000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein ML, Ferris FL, 3rd, Armstrong J, Hwang TS, Chew EY, Bressler SB, Chandra SR. Retinal precursors and the development of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, SanGiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, Bracken MB, Ferris FL, Ott J, Barnstable C, Hoh J. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:385–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1109557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz CA, Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Li ZY, Stone EM, Possin D, Milam AH. Sub-retinal pigment epithelial deposits in a dominant late-onset retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1772–1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longbottom R, Fruttiger M, Douglas RH, Martinez-Barbera JP, Greenwood J, Moss SE. Genetic ablation of retinal pigment epithelial cells reveals the adaptive response of the epithelium and impact on photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18728–18733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902593106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez PF, Yan Q, Kohen L, Rao NA, Spee C, Black J, Oganesian A. Retinal pigment epithelial wound healing in vivo. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1437–1446. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100110097032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller JB, Fagerness JA, Reynolds RC, Neale BM, Daly MJ, Seddon JM. Variation in complement factor 3 is associated with risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1200–1201. doi: 10.1038/ng2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay GJ, Silvestri G, Patterson CC, Hogg RE, Chakravarthy U, Hughes AE. Further assessment of the complement component 2 and factor B region associated with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:533–539. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin BJ, Fan W, Zheng JJ, Cai H, Del Priore LV, Bora NS, Kaplan HJ. Novel role for a complement regulatory protein (CD46) in retinal pigment epithelial adhesion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3669–3674. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod DS, Grebe R, Bhutto I, Merges C, Baba T, Lutty GA. Relationship between RPE and choriocapillaris in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4982–4991. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleth AD, Wong WT, Chew EY. Treatment for atrophic macular degeneration. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2011;22:190–193. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834594b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins RF, Russell SR, Anderson DH, Hageman GS. Drusen associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration contain proteins common to extracellular deposits associated with atherosclerosis, elastosis, amyloidosis, and dense deposit disease. Faseb J. 2000;14:835–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philp NJ, Wang D, Yoon H, Hjelmeland LM. Polarized expression of monocarboxylate transporters in human retinal pigment epithelium and ARPE-19 cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1716–1721. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philp NJ, Yoon H, Lombardi L. Mouse MCT3 gene is expressed preferentially in retinal pigment and choroid plexus epithelia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1319–C1326. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.5.C1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich RM, Rosenfeld PJ, Puliafito CA, Dubovy SR, Davis JL, Flynn HW, Jr, Gonzalez S, Feuer WJ, Lin RC, Lalwani GA, Nguyen JK, Kumar G. Short-term safety and efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26:495–511. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000225766.75009.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripps H. Night blindness revisited: from man to molecules. Proctor lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1982;23:588–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roquet W, Roudot-Thoraval F, Coscas G, Soubrane G. Clinical features of drusenoid pigment epithelial detachment in age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:638–642. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.017632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarks JP, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC. Evolution of geographic atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Eye (Lond) 1988;2(Pt 5):552–577. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarks S, Cherepanoff S, Killingsworth M, Sarks J. Relationship of basal laminar deposit and membranous debris to the clinical presentation of early age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:968–977. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarks SH. Ageing and degeneration in the macular region: a clinico-pathological study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1976;60:324–341. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.5.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G, Maminishkis A, Banzon T, Jalickee S, Li R, Hammer J, Miller SS. Control of chemokine gradients by the retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4620–4630. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda S, Sreekumar PG, Kase S, Spee C, Ryan SJ, Kannan R, Hinton DR. Attainment of polarity promotes growth factor secretion by retinal pigment epithelial cells: relevance to age-related macular degeneration. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:28–42. doi: 10.18632/aging.100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaide RF, Armstrong D, Browne R. Continuing medical education review: choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration--what is the cause? Retina. 2003;23:595–614. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200310000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spraul CW, Grossniklaus HE. Characteristics of Drusen and Bruch's membrane in postmortem eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997a;115:267–273. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150269022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spraul CW, Grossniklaus HE. Characteristics of drusen and Bruch's membrane in postmortem eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1997b;115:267–273. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150269022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg RH, Wood I, Hogan MJ. Pigment epithelial ensheathment and phagocytosis of extrafoveal cones in human retina. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 1977;277:459–474. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1977.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:845–881. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunness JS, Applegate CA, Bressler NM, Hawkins BS. Designing clinical trials for age-related geographic atrophy of the macula: enrollment data from the geographic atrophy natural history study. Retina. 2007a;27:204–210. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000248148.56560.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunness JS, Margalit E, Srikumaran D, Applegate CA, Tian Y, Perry D, Hawkins BS, Bressler NM. The long-term natural history of geographic atrophy from age-related macular degeneration: enlargement of atrophy and implications for interventional clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2007b;114:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanos B, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The epithelial polarity program: machineries involved and their hijacking by cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:6939–6957. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Schaft TL, Mooy CM, de Bruijn WC, Oron FG, Mulder PG, de Jong PT. Histologic features of the early stages of age-related macular degeneration. A statistical analysis. Ophthalmology. 1992a;99:278–286. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31982-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Schaft TL, Mooy CM, de Bruijn WC, Oron FG, Mulder PGH, de Jong PTVM. Histologic features of the early stages of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol. 1992b;99:278–286. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31982-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt SD, Barnum SR, Curcio CA, Read RW. Distribution of complement anaphylatoxin receptors and membrane-bound regulators in normal human retina. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport MJ. Complement. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001a;344:1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport MJ. Complement. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001b;344:1140–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang FE, Zhang C, Maminishkis A, Dong L, Zhi C, Li R, Zhao J, Majerciak V, Gaur AB, Chen S, Miller SS. MicroRNA-204/211 alters epithelial physiology. The FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2010a;24:1552–1571. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-125856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Clark ME, Crossman DK, Kojima K, Messinger JD, Mobley JA, Curcio CA. Abundant Lipid and Protein Components of Drusen. PLoS ONE. 2010b;5:e10329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Tornquist P, Bill A. Glucose metabolism in pig outer retina in light and darkness. Acta Physiol Scand. 1997;160:75–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1997.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler BS, Arnold MJ, Brassell MA, Sliter DR. Glucose dependence of glycolysis, hexose monophosphate shunt activity, energy status, and the polyol pathway in retinas isolated from normal (nondiabetic) rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:62–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Tyrrell J, Han I, Jaffe GJ. Expression and modulation of RPE cell membrane complement regulatory proteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3473–3481. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareparsi S, Branham KE, Li M, Shah S, Klein RJ, Ott J, Hoh J, Abecasis GR, Swaroop A. Strong association of the Y402H variant in complement factor H at 1q32 with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;77:149–153. doi: 10.1086/431426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Yasumura D, Li X, Matthes M, Lloyd M, Nielsen G, Ahern K, Snyder M, Bok D, Dunaief JL, Lavail MM, Vollrath D. mTOR-mediated dedifferentiation of the retinal pigment epithelium initiates photoreceptor degeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:369–383. doi: 10.1172/JCI44303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]