Abstract

The surface-exposed antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi represent important targets for induction of protective host immune responses. BBA52 is preferentially expressed by B. burgdorferi in the feeding tick, and a targeted deletion of bba52 interferes with vector-host transitions in vivo. In this study, we demonstrate that BBA52 is an outer membrane surface-exposed protein and that disulfide bridges take part in the homo-oligomeric assembly of native protein. BBA52 antibodies lack detectable borreliacidal activities in vitro. However, active immunization studies demonstrated that BBA52 vaccinated mice were significantly less susceptible to subsequent tick-borne challenge infection. Similarly, passive transfer of BBA52 antibodies in ticks completely blocked B. burgdorferi transmission from feeding ticks to naïve mice. Taken together, these studies highlight the role of BBA52 in spirochete dissemination from ticks to mice and demonstrate the potential of BBA52 antibody-mediated strategy to complement the ongoing efforts to develop vaccines for blocking the transmission of B. burgdorferi.

Keywords: Borrelia burgdorferi, Lyme disease, immunization, pathogen transmission

1. INTRODUCTION

Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, is a prevalent vector-borne illness in the United States and many European countries [1, 2]. The pathogen survives in nature in a tick-mammal infection cycle. Ticks acquire the pathogen from infected hosts, usually wild rodents, and subsequently transmit it to other mammals, including humans. B. burgdorferi adapts to the transition between the vector and hosts in part by preferential gene expression [3]. For instance, the production of outer surface protein (Osp) A and OspB is turned on when the spirochetes enter and reside in ticks [4, 5]. However, during transmission to a host, spirochetes downregulate many genes including ospA and induce other genes including bba52, ospC, dbpA and bbk32, which facilitate transmission from ticks and subsequent colonization of host tissues [6-12]. The predominant expression of tick-induced genes and their ability to induce protective immunity, such as OspA [13, 14], has lead to the development of an FDA-approved transmission-blocking vaccine [15, 16]. The OspA vaccine induces host antibodies that neutralize OspA expressing spirochetes in the tick gut blood meal and blocks pathogen transmission to the host [17]. Despite the impressive effectiveness of OspA vaccine in inducing protective immunity in animals and humans, the vaccine has been withdrawn from the marketplace. This is primarily due to complications arising from the need of frequent boosting to ensure high circulating OspA antibody titers, and the development of autoimmunity in some vaccinated individuals amongst other reasons. Due to limitations of the OspA-based vaccine and the lack of an alternative strategy, research efforts are warranted to identify new borrelial target antigens involved in survival and vector-host transmission of the pathogen.

B. burgdorferi BBA52, a 33-kDa gene-product is encoded on a conserved linear plasmid, lp54, which is considered as part of the core spirochete genome [18]. Our previous study showed that bba52 expression is confined to the vector-phase of the microbial life cycle, with highest expression in feeding ticks [8]. Also, a bba52 deletion mutant was impaired in its ability to migrate to salivary glands and transmit to mice suggesting that BBA52 may serve a function in the tick, possibly facilitating the dissemination of the spirochete from the vector to murine hosts [8]. In this study, we assessed the immunogenicity and cellular localization of BBA52 and subsequently evaluated the efficacy of BBA52 as a potential vaccine candidate. Active immunization of mice with recombinant BBA52 or passive administration of BBA52 antibodies to ticks has shown immense promise in its ability to protect against B. burgdorferi infection in the host.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. B. burgdorferi, ticks and mice

An infectious isolate of B. burgdorferi, B31-A3 [19], was used throughout this study. Four- to six-week-old C3H/HeN mice were purchased from the National Institutes of Health. I. scapularis ticks used in this study originated from a colony that is maintained in the laboratory [20]. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Bio-safety Committee.

2.2. Generation of recombinant BBA52 protein and BBA52 antisera

A full-length version of BBA52 was made using a Baculovirus expression system (Invitrogen). The bba52 ORF without the signal peptide sequence and a 6×His tag at N-terminus was amplified by PCR using primers containing BamHI and XhoI sites (italicized) CGG GAT CCA TGC ACC ACC ACC ACC ACC ACA GTG TTG CAA GAC CAT TTG ATT TTA and CCG CTC GAG TTA AAT AAA CTG ATC TTC AAG AGA A, respectively and cloned between the BamHI and XhoI sites of the pFastBac plasmid. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli DH10Bac™cells for homologous recombination, and the recovered Bacmid was transfected to Sf9 cells for the generation of infectious stocks. The BBA52 protein was purified using Ni-NTA (Invitrogen) affinity chromatography and antiserum was raised in rabbits. In addition, polyclonal antibodies against a BBA52 peptide sequence (EFLDDPSQESDELER) of predicted immunogenicity were generated in rabbits, as detailed [8].

2.3. Western blotting

Purified recombinant proteins or whole cell lysates of various B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE (0.1-5μg/lane), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with 1:1,000 – 5,000 dilutions of antisera against the various recombinant proteins. To assess the development of BBA52-specific antibody response during mammalian infection, serum samples collected from B. burgdorferi-infected mouse (5 animals) or 7 human patients with diagnosed Lyme disease as well as 4 normal healthy individuals were immunoblotted against recombinant BBA52 as detailed [21]. The immunoblots were developed by the addition of HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence as previously described [22].

2.4. Assessment of BBA52 oligomer formation

The oligomeric nature of BBA52 and the presence of intra- and interchain disulfide bonds were evaluated by immunoblot analysis of whole cell proteins and recombinant protein in the presence or absence of β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME; 5% [vol/vol]). To prevent post-lysis formation of disulfide bonds and further assess the degree of BBA52 oligomerization in intact cells, an alkylating agent, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) was added at a concentration of 20 mM to the cell lysis buffer. The lysates were processed for immunoblotting using BBA52 antibody as detailed [8].

2.5. Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

To examine whether BBA52 antibody binds to the surface of Borrelia cells, immunofluorescence assay was performed as described previously [8]. Briefly, intact unfixed B. burgdorferi were immobilized on glass slides and probed with BBA52 antibody. Antibody against GST and known surface protein, OspA [20] or subsurface protein, Lp6.6 [22] spirochete proteins were used as controls. Spirochete loading and antibody labeling was assessed using propidium iodide (PI) and Alexa-488 tagged secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen), respectively. Images were acquired using a 40x objective lens of a Zeiss confocal microscope. Spirochete distribution in the gut of unfed-nymphs was analyzed using confocal microscopy, as detailed [8].

2.6. Triton X-114 phase partitioning

To examine the amphiphilic characteristic of BBA52, Triton X-114 (TX-114) phase partitioning [23] was performed, as detailed [24]. Briefly, 1 × 109 spirochetes were sonicated, extracted with 10% TX-114 (Sigma Chemical Co.) and the aqueous and detergent-enriched phases were assessed by immunoblot analysis.

2.7. Proteinase K accessibility assay

Proteinase K accessibility assays were performed as detailed [25]. Degradation of Proteinase K-sensitive surface proteins was evaluated using immunoblotting with antibodies against FlaB (1:2000), OspA (1:200), BBA52 peptide (1:15000) and full-length BBA52 (1: 2000), as detailed [8].

2.8. Purification of B. burgdorferi outer membrane

Isolation of outer membrane (OM) vesicles of B. burgdorferi was performed as described [26]. OM vesicles were released from whole cells and were separated from protoplasmic cylinder (PC) using sucrose density gradient centrifugation. For localization of BBA52, immunoblotting was performed using equal amounts (0.3μg/lane) of OM vesicles and PC, and probed with BBA52 (1:2000), FlaB (1:2000), or OspA (1:200) antibodies.

2.9. Bactericidal assay

BBA52 antibodies were tested for bactericidal activities against B. burgdorferi via dark-field microscopy [27] using a re-growth assay, as described [24]. Briefly, spirochetes (5 × 106/ml) were incubated in BSK-H medium (Sigma-Aldrich,) supplemented with BBA52 full-length or peptide antibodies at 33°C. Normal rabbit sera (NRS), rabbit OspA antibodies (OspA), and anti-B. burgdorferi serum collected from 15-day infected mice served as controls. Bactericidal potential of BBA52 antibodies were performed using undiluted sera (with or without complement inactivation), which were stored at 70°C until use. At 48 h following antiserum treatment, 1 μl of medium containing spirochetes was added to 2 ml of fresh BSK-H medium to assess the spirochetes’ ability to re-grow in the culture. Spirochetes were incubated at 33°C and were enumerated by dark-field microscopy, as detailed [24].

2.10. Immunization experiments

In the active immunization study, groups of 5 mice were immunized by subcutaneously injecting either 10 μg of purified recombinant BBA52 suspended in complete Freund's adjuvant or PBS adjuvant alone (control). Mice were boosted with 10 μg of antigen suspended in incomplete Freund's adjuvant every two weeks. Two weeks after the final boost, mice were bled to measure BBA52 antibody titer by ELISA, as detailed [9], using wells coated with recombinant BBA52 (0.2μg /well). The BBA52-immunized mice were then challenged with infected ticks (2 nymphs/mouse). Mice were euthanized 7 days after the nymphs had fallen off and tested for Borrelia infection by qRT-PCR and organ culture in BSK-II medium, as detailed [8]. Infected nymphal ticks that had fed to repletion on the BBA52 and PBS-immunized mice were homogenized and the spirochete load in the nymphs was assessed by qRT-PCR.

For the passive transfer of BBA52 antibody into the infected tick gut, a microinjection procedure was used, as described [9]. Naturally-infected nymphs were generated by allowing larvae to engorge on B. burgdorferi-infected mice and molt to nymphs. Two groups of nymphs (10 ticks/group) were injected with equal amounts of BBA52 antibody raised against the carboxyl terminal peptide, as detailed in earlier paragraphs or normal rabbit antibody (control). One group of injected nymphs (5 ticks/group) was kept in the unfed condition for 5 days and spirochete burden were determined by qRT-PCR and confocal immunofluorescence, as described above. To assess the effects of BBA52 antibodies on spirochete transmission from ticks to mice, antibody-injected ticks (1 tick/mouse) were fed on groups of two naïve mice, and B. burgdorferi burden in the repleted ticks were determined by qRT-PCR analysis. At day 7, following tick repletion, all the mice were sacrificed, and the tissues were isolated for the assessment of spirochete burden by qRT-PCR and culture analysis [8]. Two independent experiments were performed and the average of the results obtained was statistically analyzed.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SEM). The significance of the difference between the mean values of the groups was evaluated by two-tailed Student's t-test.

3. RESULTS

3.1. BBA52 exists as homo-oligomers in B. burgdorferi

B. burgdorferi BBA52 is a putative outer-membrane protein [28] and has recently been identified to assist in spirochete transmission from the vector to the host [8]. This prompted us to characterize BBA52 and its potential role as target of transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccines. Characterization of BBA52 required its production as recombinant proteins; however, its expression in tested E. coli strains yielded lower quantities of purified protein. Therefore, a baculovirus expression system was employed for improved production of BBA52 (Fig. 1A). Rabbit antiserum was generated which readily detected recombinant and native BBA52 with minor cross-reactivity to other proteins (Fig. 1B, left and middle lanes). Under non-reducing conditions, both recombinant (data not shown) and native BBA52 predominantly existed as a trimeric protein of 90 kDa (Fig. 1B, right lane). Notably, both the monomeric and oligomeric BBA52 appeared as doublet proteins of closer molecular weight (arrows, Fig. 1B, right lane) suggesting existence of both inter- and intra-molecular disulfide bonds. In fact, predicted amino acid sequence of BBA52 [28, 29] reflects occurrence of two cysteine residues at positions 78 and 202. To assess if disulfide bridges are responsible for oligomerization of BBA52 in intact cells, we treated spirochetes with NEM, which quenches free thiol groups and prevents isomerization of existing disulfide bonds and block formation of artificial disulfide bridges after cell lysis. As shown in Fig. 1C, NEM-treated cells also displayed doublets of corresponding BBA52 oligomers including most prominent trimers, in the absence of β-ME, consistent with the interpretation that native BBA52 in B. burgdorferi formed oligomeric complexes involving both inter- and intra-molecular disulfide bonds. Also, BBA52 antibodies generated against B31 isolates readily recognized orthologues in tested infectious isolates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato species (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Characterization of recombinant and native BBA52.

(A) Recombinant BBA52. Production of recombinant BBA52 in insect cells using baculovirus expression system (left panel, purified recombinant BBA52, arrow). (B) Immunoblot analysis of recombinant BBA52 (middle panel), or B. burgdorferi lysates (right panel) in the presence or absence of β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME). Note that in addition to monomeric form, native BBA52 exists as higher-order oligomer (arrows) in the absence of β-ME. (C) Native BBA52 exists as oligomeric protein in B. burgdorferi cells. Spirochetes cells were lysed in the presence or absence of N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) and assessed using BBA52 antibody. The oligomerization property of BBA52 under non-reducing conditions remained unaltered in the presence of NEM, indicating that major fraction of native BBA52 exists in trimeric conformation (arrow). Note that except for trimeric conformation, other relatively less abundant forms of native BBA52 appeared as faint bands (arrowheads). (D) Production of BBA52 in major infectious strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. B. burgdorferi cell-lysates prepared from isolates B31, 297 or N40 and B. garinii isolate PBi were immunoblotted with anti-BBA52 antibody generated against B. burgdorferi B31 isolate.

3.2. BBA52 is an outer membrane antigen that is exposed in the microbial surface via carboxyl-terminal end

Since B. burgdorferi BBA52 is annotated as an outer membrane protein, we sought to assess the precise cellular distribution of BBA52. To accomplish this, spirochetes were separated into outer membrane (OM) vesicles and protoplasmic cylinder (PC) fractions, and subjected to immunoblot analyses. OspA and FlaB served as controls for representative proteins of OM and PC fractions respectively. Unlike FlaB, both BBA52 and OspA fractionated into OM suggesting the existence of BBA52 as an outer membrane protein (Fig. 2A). However, a major fraction of BBA52 was associated with the protoplasmic cylinder indicating its possible association with inner membrane. Triton X-114 phase partitioning studies [24] further demonstrated that similar to known amphiphilic membrane protein OspA [25], BBA52 partitioned into both aqueous and detergent phase whereas a known hydrophilic protein BBA74 [30] separated exclusively into the aqueous phase (Fig. 2B). Together, these findings suggest that BBA52 is an outer membrane associated protein.

Figure 2. BBA52 is an outer membrane protein and is exposed on the microbial surface via carboxyl terminus.

(A) BBA52 is distributed in the outer membrane of cultured spirochetes. B. burgdorferi protoplasmic cylinders (PC) and outer membranes (OM) were separated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Equal amounts of protein from two sub-cellular fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with BBA52, OspA and FlaB antiserum. (B) Triton-X-114 phase partitioning of B. burgdorferi proteins. Spirochete lysates were subjected to Triton X-114 phase partitioning of aqueous and detergent phases and immunoblotted using BBA52 antibody or antibodies against known hydrophilic (BBA74) protein. (C) Association of BBA52 with borrelial membranes as assessed by the salt and detergent treatment. B. burgdorferi preparations were treated with indicated PBS, salt, detergent or sonication as described in the text. Supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were separated by centrifugation and assessed by immunoblot analysis using BBA52 or FlaB antibody. (D) BBA52 is exposed on the B. burgdorferi surface via the carboxyl terminus. Viable spirochetes were incubated with (+) or without (–) proteinase K for the removal of protease-sensitive surface proteins and processed for immunoblot analysis using antibodies raised against full-length BBA52 or against a carboxyl terminus peptide of the protein. B. burgdorferi OspA and FlaB antibodies were utilized as controls for surface exposed and sub-surface proteins, respectively.

Given the lack of identifiable lipidation or transmembrane motifs, exactly how BBA52 is associated with borrelial membrane remains unknown. To address this, spirochetes were subjected to salt treatments that are known to disrupt the OM and release periplasmic proteins and proteins that are loosely associated with the OM or with the outer leaflet of the IM [31, 32]. Spirochetes were treated with salts, detergents or sonication, and cell supernatant and pellet fractions were immunoblotted with BBA52 or FlaB antibodies. In cases of salt treatment or sonication, BBA52 remained exclusively in the pelleted membrane fraction while periplasmic FlaB was released into the supernatant (Fig. 2C). In comparison, detergent treatment liberated both BBA52 and FlaB into the supernatant (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that unlike salt-extractable peripheral outer membrane proteins described in other spirochetes [33], BBA52 is tightly associated with the cellular membrane.

As above experiments demonstrated the existence of BBA52 as an outer membrane antigen, we further assessed its exposure on the microbial surface. To accomplish this, intact spirochetes were subjected to a controlled proteinase K (PK) digestion and then assessed by immunoblot analysis using antisera against BBA52 or known surface (OspA) or subsurface (FlaB) antigens. The results suggested that BBA52 is exposed on the borrelial surface (Fig. 2D). A subsequent PK-digestion assay using antibodies raised against a specific region of BBA52 further suggested that the carboxyl-terminus of the protein is exposed to the surface (Fig. 2D).

3.3. BBA52 antibodies bind to the microbial surface and lack borreliacidal activity in vitro

To assess if the BBA52 antibody could bind to the surface of B. burgdorferi, an indirect immunofluorescence assay was used. Antibodies against GST and known B. burgdorferi surface (OspA) or subsurface (Lp6.6) proteins were used as controls. As shown in Fig. 3A both anti-BBA52 and anti-OspA bound to the surface of intact borreliae. However as expected, both anti-GST and anti-Lp6.6 lacked surface-binding abilities (Fig. 3A). Since BBA52 could be readily detected on the surface of intact bacteria, these results suggest that the BBA52 protein has antibody accessible epitope(s) on the pathogen surface. However, no significant bactericidal activity was found when B. burgdorferi cells were exposed to antibodies (undiluted sera with or without complement inactivation) against either full-length BBA52 (data not shown) or C-terminal peptide of BBA52 (Fig. 3B) whereas antibodies directed against OspA or B. burgdorferi readily killed the spirochetes (Fig. 3B). These data suggests that BBA52 antibody, either in the presence or absence of complement, lacks measurable borreliacidal activities in vitro.

Figure 3. BBA52 antibodies bind to the surface of B. burgdorferi but lack borreliacidal activities in vitro.

(A) BBA52 antibodies bind to the surface of intact unfixed B. burgdorferi (arrow). Spirochetes were immobilized on glass slides and probed with BBA52 or control (GST) antibodies. Antibody against known surface (OspA) and subsurface (Lp6.6) spirochete proteins were used as controls. Spirochete (arrow) loading and antibody labeling was assessed using propidium iodide (PI) and Alexa-488 tagged secondary antibodies, respectively. Images were acquired using a 40x objective lens of a Zeiss confocal microscope. (B) BBA52 antibodies lack borreliacidal activities in culture. Spirochetes were incubated without serum (control) or in the presence of either normal rabbit sera (NRS), rabbit OspA antibodies (OspA), serum collected from 15-day infected mice or peptide antibodies raised against carboxyl terminus of BBA52. The sensitivity of spirochetes to the bactericidal effects of the antibodies was assessed by a re-growth assay after 48 h of antibody incubation and presented as mean ± SEM of viable spirochete number (cells/ml). The numbers of viable spirochetes were significantly reduced in the samples exposed to the OspA or B. burgdorferi antibodies, compared to spirochetes that received no treatment or were incubated with BBA52 antibodies or normal serum (P < 0.002).

3.4. Active immunization of mice with BBA52 interferes with B. burgdorferi transmission from ticks to naïve hosts

Since BBA52 was identified as a surface-exposed protein and our previous studies show that spirochetes induced BBA52 within ticks during engorgement facilitating Borrelia transmission [8], we next examined whether BBA52 antisera generated in mice via active immunization could interfere with BBA52 function in the feeding vector and influence spirochete transmission to naïve hosts. To accomplish this, separate groups of C3H mice (5 animals/group) were immunized with either recombinant BBA52 (Fig. 1A) or PBS in the presence of similar volume of adjuvant (control). ELISA (Fig. 4A) and immunoblot (data not shown) analyses confirmed that the immunized mice had developed a strong BBA52 antibody titer. Two weeks after the final immunization, mice were parasitized by B. burgdorferi-infected nymphs (2 ticks/mouse). The spirochete burden in engorged ticks was determined by qRT-PCR, which indicated that BBA52 antibody did not affect persistence of B. burgdorferi in feeding ticks (data not shown). Strikingly, qRT-PCR analysis of mouse infection following one week of tick engorgement indicated that, unlike the control, BBA52 immunization significantly blocked the transmission of spirochetes from ticks to mice (Fig. 4B). However, spirochetes were recovered from each of the murine skin and the spleen samples by culture analysis regardless of whether they were immunized with recombinant BBA52 or PBS (data not shown). This result demonstrates the ability of an unknown fraction of spirochetes to evade BBA52 elicited protective immunity and colonize different organs in the immunized hosts.

Figure 4.

Active immunization of mice with recombinant BBA52 induces robust antibody responses and interfere with spirochete transmission from infected ticks to naïve hosts. A) ELISA showing development of high-titer serum antibodies induced in recombinant BBA52-immunized mice. Groups of C3H mice (5 animals/group) were immunized with recombinant BBA52, and two weeks after final immunization, serum was collected and subjected to ELISA. The wells were coated with recombinant BBA52 and probed either with BBA52 antiserum (black bars) or normal mouse serum (NMS, white bars) serially diluted from 1,000 -128,000. Differences between the OD values of wells probed with BBA52 antiserum with respective control wells treated with NMS were significant (P < 0.05). B) Active immunization of mice with recombinant BBA52 significantly interferes with spirochete transmission from infected ticks. Mice (5 animals/group) were immunized with either BBA52 or PBS (control) mixed with an equal amount of adjuvant, as described in Figure 4A. Two weeks after final immunization, B. burgdorferi-infected nymphs were allowed to engorge on naive immunized mice (2 ticks/mouse) and murine skin, heart and bladder samples were assessed for spirochete transmission after 7 days of feeding. Total RNA was isolated from murine samples, and B. burgdorferi flaB was measured using quantitative RT-PCR. Amount of murine β-actin was determined in each sample and used to normalize the quantities of spirochete RNA. The entire animal immunization and challenge studies were independently repeated three times and the bars represent the mean measurements ± SEM of three experiments reflecting similar results. Difference in the spirochete transmission in BBA52 immunized group with the control PBS group is significant (*P < 0.05).

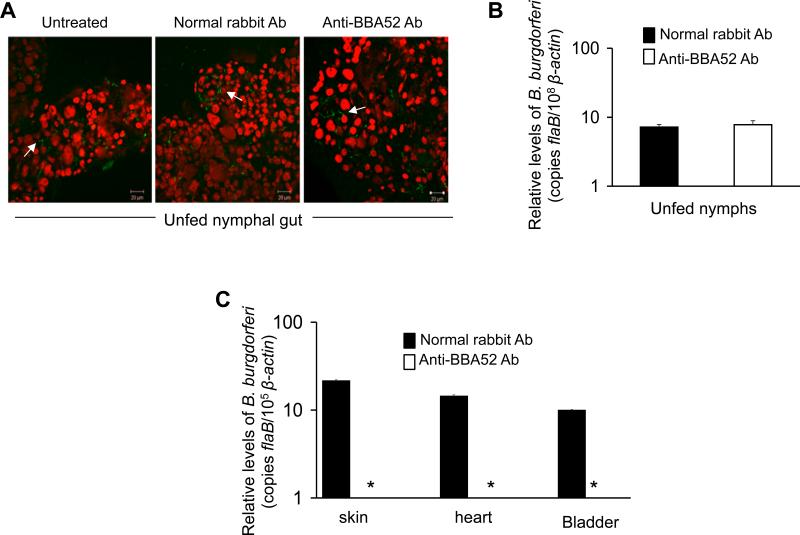

3.5. Passive transfer of antibodies against carboxyl-terminus of BBA52 in ticks block transmission of B. burgdorferi to murine hosts

Our PK-digestion assay (Fig. 2D) indicated that unlike major subsurface portion of the antigen, carboxyl-terminus of BBA52 is exposed on the microbial surface. We next assessed whether passive transfer of antibodies raised against the surface-exposed carboxyl-terminus of BBA52 in ticks could exert a greater effect on Borrelia transmission than what was achieved through active immunization studies. To examine this, ticks were injected with similar amounts of normal rabbit antibodies or BBA52 peptide antibodies. We found comparable spirochete burdens in dissected gut contents from different groups of injected ticks, as assessed by confocal immunofluorescence (Fig. 5A) and qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 5B). Next, parallel groups of injected ticks were allowed to engorge on naïve C3H mice (1 tick/mouse). The qRT-PCR assessment of spirochete burdens in fed ticks indicated that, similar to unfed nymphs (Fig. 5B), BBA52 antibody did not affect the persistence of B. burgdorferi in feeding ticks (data not shown). However, qRT-PCR analysis of mouse infection following one week of tick engorgement indicated that, unlike the control antibody, BBA52 antibody treatment effectively blocked the transmission of spirochetes from ticks to mice (Fig. 5C). Culture analyses corroborated these data showing that while B. burgdorferi is readily recovered from murine skin, spleen and heart tissues in control antibody-treated groups (5 out of 5 tissues were culture positive), the mice fed on by BBA52 antibody-treated ticks remained culture negative at all tissue locations (8 out of 8 tissues were culture negative). Combined together the data presented herein, and our previous genetic studies [8] establish that BBA52 facilitates B. burgdorferi transitions from feeding ticks to the murine hosts and that surface-exposed region of BBA52 may serve as an antigenic target for protective antibodies to interfere with borrelial transmission.

Figure 5. Passive transfer of BBA52 antibodies in ticks interfere with B. burgdorferi transmission to mice.

(A) Passive transfer of antibodies raised against a carboxyl-terminal BBA52 peptide does not interfere with spirochete persistence in unfed ticks. Naturally-infected nymphal ticks were microinjected with equal amounts of antibodies against BBA52 peptide (anti-BBA52 Ab) or control antibody (normal rabbit Ab), and spirochete distribution in the gut of unfed ticks were analyzed 5 days after injection. Spirochetes (arrow) were labeled with FITC-labeled goat anti-B. burgdorferi antibody (shown in green), and the nuclei of the gut cells were stained with propidium iodide (shown in red). Images were obtained using a confocal immunofluorescence microscope and presented as merged image for clarity. (B) Quantitative representation of the data shown in Fig. 5A. B. burgdorferi burden in ticks were assessed by qRT-PCR analysis by measuring copies of the B. burgdorferi flaB RNA and normalized against tick β-actin levels. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of four qRT-PCR analyses derived from two independent infection experiments. Spirochete burdens in BBA52 antibody-treated ticks are similar to the control ticks (P > 0.05). (C) BBA52 peptide antibodies blocked transmission of B. burgdorferi from ticks to mice. Naturally infected nymphal ticks were microinjected with antibodies as described in Fig. 5A and placed on naive mice 48 h after injection. Ticks were allowed to fully engorge on mice and the transmission of B. burgdorferi was assessed by measuring copies of the B. burgdorferi flaB gene in the indicated murine tissues 7 days after tick feeding. Amounts of mouse β-actin were determined in each sample and used to normalize the quantities of B. burgdorferi flaB. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of relative tissue levels of B. burgdorferi from two independent animal experiments showing similar results. * Spirochetes were undetectable in the anti-BBA52 Ab group.

4. DISCUSSION

Our recent gene inactivation studies demonstrated that BBA52 is directly involved in host infection by assisting pathogen transmission from the vector [8]. BBA52 orthologues exist among all sequenced isolates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, as well as in relapsing fever Borrelia species. This extensive conservation among tick-borne spirochete pathogen suggests that bba52 may be used by diverse Borrelia species for successful persistence in a tick-rodent transmission cycle. Although the precise mechanism by which bba52 serves to facilitate borrelial transmission remains unclear, data presented herein support the contention that bba52 should be included among a crucial set of genes, such as ospA [34], ospB [35], ospC [9], dps [36], btpA [37] and lp6.6 [22] which impact vector-associated events crucial to spirochete persistence in tick-rodent infection cycle. Although more in-depth analysis is required for the use of BBA52 as a Lyme vaccine, our studies conclusively established that the protein, as a surface-exposed antigen that is the target of host-generated antibodies in the tick blood meal, especially the carboxyl terminus of the antigen, is a potential candidate for the development of effective transmission-blocking vaccines.

Our results suggest that similar to certain lipoproteins, such as OspA, OspB or Lp6.6. [38-40], BBA52 reflects a dual-membrane distribution in spirochetes. Although the exact function of BBA52 in spirochete biology is unknown, the trimeric and higher order homo-oligomeric organization properties in the outer membrane tempts us to speculate its role as a potential porin. Additionally, the surface-exposed region of BBA52 can potentially interact to cellular receptors, a feature previously recorded for other proteins with porin activity, such as P66 adhesin of B. burgdorferi [41-43], OmpC of Shigella flexeneri [44] and Msp of Treponema denticola [45]. However, none of the topology prediction algorithms used could identify any β-barrel topology characteristics of a membrane-spanning porin. Alternatively, BBA52 could play a role in other diverse biological processes related to signal transduction, transportation of nutrients across the cell membrane or other unidentified cellular function relevant to oligomeric surface-exposed outer membrane proteins.

BBA52 is quickly downregulated during mammalian infection [8], and accordingly, we were unable to detect BBA52-specific antibody response during B. burgdorferi infection of murine hosts or in humans diagnosed with Lyme disease (data not shown). However, BBA52 is induced in feeding ticks [8], and in agreement with previous genetic studies [8], our active immunization results suggested that BBA52 antisera interfered with B. burgdorferi transmission from ticks to hosts. As previously shown in case of another transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine target, OspA [17], immunization with recombinant BBA52 induces antibodies in the host that likely enter the gut of infected feeding ticks and prevent the transmission of spirochetes from the vector to the host. Although this immunization strategy reduced transmission however, it failed to exert complete inhibition. The immunogen used in our studies was produced in eukaryotic cells. Therefore, one can argue that this approach could potentially introduce aberrant post-translational modifications in bacterial proteins [46] masking protective epitopes. However, our data indicate this is not the case with BBA52 as it behaves like native protein, at least in terms of its molecular weight and oligomerization properties. Thus, a lesser effect of BBA52 active immunization on borrelial transmission could be attributed to sub-optimal antibody transport or degradation within the gut or due to insufficient concentration of protective IgG that are able to bind the surface exposed portion of BBA52. The latter speculation is particularly supported by our passive immunization studies involving BBA52 peptide antibody that binds to the surface-exposed carboxyl-terminus of the antigen and exerted a greater effect on borrelial transmission. Currently, we do not know exactly how BBA52 antibody blocks spirochete transmission but such effects may not be due to the bactericidal action of the antibody or its indirect effects on tick biology. As BBA52 is a surface-exposed protein, the antibody binding could potentially interfere with BBA52 function in disseminating spirochetes including its possible interaction with the vector environment, as previously demonstrated for B. burgdorferi OspA and its tick receptor [47]. Regardless of the precise mechanism(s) by which BBA52 facilitates borrelial transmission, our studies support the notion that BBA52 may represent a new vaccine target, at least as a component of a potential multivalent transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine that may be useful to combat B. burgdorferi infection.

Highlights.

BBA52 is an outer membrane and surface-exposed protein of Lyme disease pathogen >

BBA52 antibody lacks bactericidal activities in vitro but binds to pathogen surface >

BBA52 vaccinated mice are less susceptible to infection with Lyme disease pathogen

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Allergy And Infectious Diseases (Award Number R01AI080615 to U.P). We sincerely thank Justin D. Radolf, Melissa J. Caimano, Aravinda M. de Silva, Kamoltip Promnares, Deborah Y. Shroder and Xinyue Zhang for their excellent help with this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Piesman J, Eisen L. Prevention of Tick-Borne Diseases. Annu Rev Entomol. 2008;53:323–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. The emergence of Lyme disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(8):1093–101. doi: 10.1172/JCI21681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Silva AM, Fikrig E. Arthropod- and host-specific gene expression by Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(3):377–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI119169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pal U, Fikrig E. Adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the vector and vertebrate host. Microbes Infect. 2003;5(7):659–66. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwan TG, Piesman J. Temporal changes in outer surface proteins A and C of the Lyme disease- associated spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, during the chain of infection in ticks and mice. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(1):382–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.382-388.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimm D, Tilly K, Byram R, Stewart PE, Krum JG, Bueschel DM, et al. Outer-surface protein C of the Lyme disease spirochete: a protein induced in ticks for infection of mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(9):3142–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306845101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo BP, Brown EL, Dorward DW, Rosenberg LC, Hook M. Decorin-binding adhesins from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30(4):711–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar M, Yang X, Coleman AS, Pal U. BBA52 facilitates Borrelia burgdorferi transmission from feeding ticks to murine hosts. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(7):1084–95. doi: 10.1086/651172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pal U, Yang X, Chen M, Bockenstedt LK, Anderson JF, Flavell RA, et al. OspC facilitates Borrelia burgdorferi invasion of Ixodes scapularis salivary glands. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(2):220–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI19894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Probert WS, Johnson BJ. Identification of a 47 kDa fibronectin-binding protein expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi isolate B31. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30(5):1003–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwan TG, Piesman J, Golde WT, Dolan MC, Rosa PA. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(7):2909–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Xu Q, McShan K, Liang FT. Both decorin-binding proteins A and B are critical for the overall virulence of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2008 Mar;76(3):1239–46. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00897-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fikrig E, Barthold SW, Kantor FS, Flavell RA. Protection of mice against the Lyme disease agent by immunizing with recombinant OspA. Science. 1990;250:553–6. doi: 10.1126/science.2237407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon MM, Schaible UE, Kramer MD, Eckerskorn C, Museteanu C, Muller-Hermelink HK, et al. Recombinant outer surface protein A from Borrelia burgdorferi induces antibodies protective against spirochetal infection in mice. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:123–32. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigal LH, Zahradnik JM, Lavin P, Patella SJ, Bryant G, Haselby R, et al. A vaccine consisting of recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface protein A to prevent Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(4):216–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steere AC, Sikand VK, Meurice F, Parenti DL, Fikrig E, Schoen RT, et al. Vaccination against Lyme disease with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface lipoprotein A with adjuvant. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(4):209–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Silva AM, Telford SR, Brunet LR, Barthold SW, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi OspA is an arthropod-specific transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine. J Exp Med. 1996;183(1):271–5. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terekhova D, Iyer R, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. Comparative genome hybridization reveals substantial variation among clinical isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto with different pathogenic properties. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(17):6124–34. doi: 10.1128/JB.00459-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elias AF, Stewart PE, Grimm D, Caimano MJ, Eggers CH, Tilly K, et al. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect Immun. 2002;70(4):2139–50. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2139-2150.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Yang X, Kumar M, Pal U. BB0323 function is essential for Borrelia burgdorferi virulence and persistence through tick-rodent transmission cycle. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(8):1318–30. doi: 10.1086/605846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman AS, Pal U. BBK07, a dominant in vivo antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi, is a potential marker for serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009 Sep 23; doi: 10.1128/CVI.00301-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Promnares K, Kumar M, Shroder DY, Zhang X, Anderson JF, Pal U. Borrelia burgdorferi small lipoprotein Lp6.6 is a member of multiple protein complexes in the outer membrane and facilitates pathogen transmission from ticks to mice. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74(1):112–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordier C. Phase separation of integral membrane proteins in Triton X-114 solution. J Biol Chem. 1981;256(4):1604–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang X, Lenhart TR, Kariu T, Anguita J, Akins DR, Pal U. Characterization of unique regions of Borrelia burgdorferi surface-located membrane protein 1. Infect Immun. 2010;78(11):4477–87. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00501-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks CS, Vuppala SR, Jett AM, Akins DR. Identification of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface proteins. Infect Immun. 2006;74(1):296–304. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.296-304.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skare JT, Shang ES, Foley DM, Blanco DR, Champion CI, Mirzabekov T, et al. Virulent strain associated outer membrane proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(5):2380–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI118295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pal U, Montgomery RR, Lusitani D, Voet P, Weynants V, Malawista SE, et al. Inhibition of Borrelia burgdorferi-tick Interactions in vivo by outer surface protein A antibody. J Immunol. 2001;166(12):7398–403. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, Lathigra R, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390(6660):580–6. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casjens S, Palmer N, van Vugt R, Huang WM, Stevenson B, Rosa P, et al. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35(3):490–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulay VB, Caimano MJ, Iyer R, Dunham-Ems S, Liveris D, Petzke MM, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi bba74 is expressed exclusively during tick feeding and is regulated by both arthropod- and mammalian host-specific signals. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(8):2783–94. doi: 10.1128/JB.01802-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts DM, Theisen M, Marconi RT. Analysis of the cellular localization of Bdr paralogs in Borrelia burgdorferi, a causative agent of lyme disease: evidence for functional diversity. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(15):4222–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4222-4226.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skare JT, Champion CI, Mirzabekov TA, Shang ES, Blanco DR, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Porin activity of the native and recombinant outer membrane protein Oms28 of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1996;178(16):4909–18. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4909-4918.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cullen PA, Haake DA, Adler B. Outer membrane proteins of pathogenic spirochetes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004 Jun;28(3):291–318. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang XF, Pal U, Alani SM, Fikrig E, Norgard MV. Essential role for OspA/B in the life acycle of the Lyme disease spirochete. J Exp Med. 2004;199(5):641–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neelakanta G, Li X, Pal U, Liu X, Beck DS, Deponte K, et al. Outer Surface Protein B Is aCritical for Borrelia burgdorferi Adherence and Survival within Ixodes Ticks. PLoS Pathog. a2007;3(3):e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Pal U, Ramamoorthi N, Liu X, Desrosiers DC, Eggers CH, et al. The Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi requires BB0690, a Dps homologue, to persist within ticks. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63(3):694–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Revel AT, Blevins JS, Almazan C, Neil L, Kocan KM, de la Fuente J, et al. bptA (bbe16) is essential for the persistence of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, in its natural tick vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(19):6972–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502565102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brusca JS, McDowall AW, Norgard MV, Radolf JD. Localization of outer surface proteins A and B in both the outer membrane and intracellular compartments of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1991;173(24):8004–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.8004-8008.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cox DL, Akins DR, Bourell KW, Lahdenne P, Norgard MV, Radolf JD. Limited surface exposure of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(15):7973–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lahdenne P, Porcella SF, Hagman KE, Akins DR, Popova TG, Cox DL, et al. Molecular characterization of a 6.6-kilodalton Borrelia burgdorferi outer membrane-associated lipoprotein (lp6.6) which appears to be downregulated during mammalian infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65(2):412–21. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.412-421.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bergström S, Zückert WR. Structure, Function and Biogenesis of the Borrelia Cell Envelope. In: Samuels DS, Radolf JD, editors. Borrelia, Molecular Biology, Host Interaction and Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press; Norfolk, UK: 2010. pp. 139–66. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skare JT, Mirzabekov TA, Shang ES, Blanco DR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Bunikis J, et al. The Oms66 (p66) protein is a Borrelia burgdorferi porin. Infect Immun. 1997;65(9):3654–61. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3654-3661.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coburn J, Cugini C. Targeted mutation of the outer membrane protein P66 disrupts attachment of the Lyme disease agent, Borrelia burgdorferi, to integrin alpha-v-beta-3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(12):7301–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131117100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernardini ML, Sanna MG, Fontaine A, Sansonetti PJ. OmpC is involved in invasion of epithelial cells by Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 1993 Sep;61(9):3625–35. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3625-3635.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fenno JC, Muller KH, McBride BC. Sequence analysis, expression, and binding activity of recombinant major outer sheath protein (Msp) of Treponema denticola. J Bacteriol. 1996;178(9):2489–97. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2489-2497.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gipson CL, Davis NL, Johnston RE, de Silva AM. Evaluation of Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis (VEE) replicon-based Outer surface protein A (OspA) vaccines in a tick challenge mouse model of Lyme disease. Vaccine. 2003;21(25-26):3875–84. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pal U, Li X, Wang T, Montgomery RR, Ramamoorthi N, Desilva AM, et al. TROSPA, an Ixodes scapularis receptor for Borrelia burgdorferi. Cell. 2004;119(4):457–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]