Abstract

Exenatide once-weekly (EQW [2 mg s.c.]) is under development as monotherapy as an adjunct to diet and exercise or as a combination therapy with an oral antidiabetes drug(s) in adults with type 2 diabetes. This long-acting formulation contains the active ingredient of the original exenatide twice-daily (EBID) formulation encapsulated in 0.06-mm-diameter microspheres of medical-grade poly-(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLG). After mechanical suspension and subcutaneous injection by the patient, EQW microspheres hydrate in situ and adhere to one another to form an amalgam. A small amount of loosely bound surface exenatide, typically less than 1%, releases in the first few hours, whereas drug located in deeper interstices diffuses out more slowly (time to maximum, ∼2 weeks). Fully encapsulated exenatide (i.e., drug initially inaccessible to diffusion) releases over a still longer period (time to maximum, ∼7 weeks) as the PLG matrix hydrolyzes into lactic acid and glycolic acid, which are subsequently eliminated as carbon dioxide and water. For EQW, plasma exenatide concentrations reach the therapeutic range by 2 weeks and steady state by 6–7 weeks. This gradual approach to steady state seems to improve tolerability, as nausea is less frequent with EQW than EBID. EQW administrations may be associated with palpable skin nodules that generally resolve without further medical intervention. In comparative trials, EQW improved hemoglobin A1c more than EBID, sitagliptin, pioglitazone, or insulin glargine and reduced fasting plasma glucose more than EBID. Weight loss due to EQW or EBID was similar. EQW is the first glucose-lowering agent that is administered once weekly.

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a growing class of biologics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.1 Including exenatide,2,3 liraglutide,4,5 and various investigational agents,1,6 these drugs mimic the activities of GLP-1, a hormone that is released from specialized intestinal L-cells in response to nutrient ingestion.1 GLP-1 is responsible, in part, for the so-called incretin effect (i.e., the augmented insulin response to oral versus intravenous glucose). Activation of GLP-1 receptors in the pancreas and digestive tract stimulates glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppresses glucagon secretion, and slows gastric emptying, all of which lower blood glucose.1 GLP-1 receptor activation in the hypothalamus also promotes satiety and reduces food intake, which can lead to weight loss.1

Exenatide, the first GLP-1 receptor agonist approved for clinical use, is a synthetic version of the naturally occurring Heloderma suspectum peptide exendin-4 and has an amino acid sequence approximately 50% identical to that of human GLP-1.1 Following subcutaneous administration, exenatide twice-daily (EBID) was shown to reach its peak plasma concentration in 2.1 h and to be eliminated subsequently with a terminal half-life of 2.4 h.7 In randomized clinical trials, subcutaneous administration of EBID decreased hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, lowered postprandial and fasting glucose, and reduced weight in patients with type 2 diabetes.2,3 Extraglycemic effects were also observed, including blood pressure lowering, small decreases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, increases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and decreases in fasting triglyceride levels.8

Several technical approaches have been used to extend the activities of GLP-1 receptor agonists.1,6 Liraglutide is a modified form of mammalian GLP-1 that has an amino acid substitution at position 34 (Ser to Arg) and a C16 palmitoyl fatty acid side chain at Lys26. These changes facilitate the drug's binding to serum albumin, promote its self-oligomerization, and increase its resistance to dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), thereby allowing for once-daily injection.1 A second GLP-1 receptor agonist, taspoglutide, contains two α-aminoisobutyric acid substitutions at positions 8 and 35 of human GLP-1, which makes the agent fully resistant to DPP-4 and allow for once-weekly dosing.1,6 Clinical development of taspoglutide was recently halted because of a higher than expected incidence of hypersensitivity reactions in clinical trials.9,10 Three additional once-weekly agents are under development, each engineered as a fusion protein or conjugate between a GLP-1 receptor agonist and a larger “carrier moiety” that slows in vivo clearance. These agents include albiglutide (fusion between a DPP-4-resistant dimer of GLP-1 and human albumin), dulaglutide (fusion between a DPP-4-resistant GLP-1 analog and modified immunoglobulin G4 Fc fragment), and CJC-1134-PC (covalent conjugate between exendin-4 and human recombinant albumin).1,6

The purpose of the present review is to describe the technology underlying a new exenatide once-weekly (EQW) formulation and to compare its efficacy and safety profiles with those of EBID.

Microsphere Technology

General features

EQW is based on the Medisorb® microsphere technology (Alkermes, Inc., Waltham, MA). Other pharmaceuticals utilizing this technology include RISPERDAL® CONSTA® (Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Titusville, NJ), an extended-release formulation of the atypical antipsychotic risperidone that is used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,11–13 VIVITROL® (Alkermes), an extended-release formulation of naltrexone that is used to treat alcohol and opioid dependence,14,15 and Sandostatin LAR® (Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Wast Hanover, NJ), a long-acting release formulation of octreotide that is used to treat acromegaly, severe diarrhea associated with metastatic carcinoid tumors, and profuse watery diarrhea associated with vasoactive intestinal peptide-secreting tumors.16 Healthcare professionals must administer RISPERDAL CONSTA by deep intramuscular deltoid or gluteal injection every 2 weeks17 and VIVITROL and Sandostatin LAR by intramuscular gluteal injection every 4 weeks.16,18 By comparison, EQW is administered subcutaneously by patients or their caregivers.

In general terms, the proprietary Medisorb technology encapsulates a medication of interest in injectable microspheres that slowly degrade in situ and release drug into circulation in a sustained fashion. The structural matrix of the microsphere is composed of a medical-grade biodegradable polymer called poly-(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLG) (Fig. 1a), which has been used in surgical sutures, bone plates, and orthopedic implants for decades19–21 and in microsphere form as a long-acting drug delivery system since 1984.18 Degradation of the PLG polymer occurs by natural (i.e., noncatalyzed) hydrolysis of the ester linkages into lactic acid and glycolic acid, which are naturally occurring substances that are easily eliminated as carbon dioxide and water.

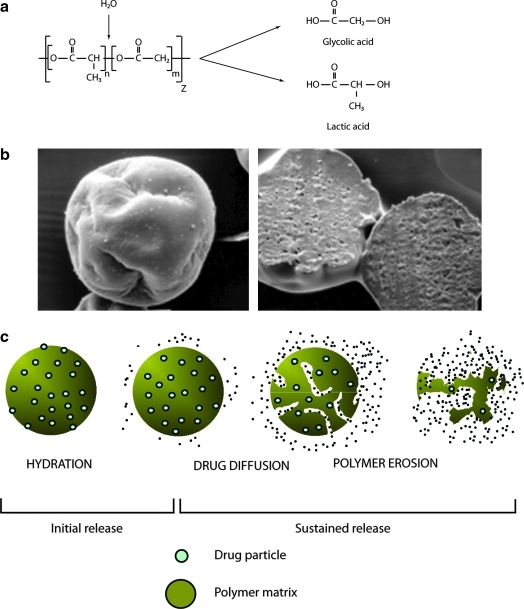

FIG. 1.

Basics of poly-(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. (a) Spontaneous hydrolysis of poly-(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) polymers. (b) Exenatide once-weekly microspheres exhibiting (left) a typical pinched raisin shape and (right) dense surface layer. (c) Mechanism of drug release from poly-(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres.

It is important to note that the encapsulated exenatide in EQW, as well as the active agent that is released into circulation, is identical to that in EBID (i.e., the sustained release arises solely from the microspheres). In scanning electron micrographs, nonhydrated EQW microspheres have a pinched or shriveled appearance and a dense surface layer (Fig. 1b), features that arise during an extraction step in the manufacturing process. The microsphere beads are approximately 0.06 mm in size (upper end of distribution, 0.1 mm), which is roughly equivalent to the diameter of a human hair.

Medication release occurs in three stages, known as initial, diffusion, and erosion release (Fig. 1c). During initial release, loosely bound and easily accessible drug molecules on or close to the surface are liberated as the microspheres hydrate immediately post-administration. Blood drug concentrations may rise transiently during this stage, which is an important consideration for medications that use this technology. The drug release profile then enters a “lag phase” as the polymer hydrolyzes into smaller fragments. Once the polymer molecular size declines to approximately 20 kDa, diffusion release initiates, during which time drug molecules enter the circulation at a relatively constant rate from interstices of the microsphere fragments. It might be expected that the kinetics of diffusion release would change as the diameter of the microspheres decreases, owing to the increased ratio of surface area to volume. However, because the microspheres are soft and sticky when wet at body temperature and because hydrated microspheres tend to “fuse” together into amalgams, their initial diameter has only a minor effect on diffusion release, but may affect injectability and needle-gauge selection. Finally, during erosion release, the PLG matrix fully hydrolyzes, leading eventually to the end of drug liberation. Time between initial injection and the end stage varies according to manufacturing parameters, but the process may extend over months for some formulations.

Controlling drug release from microspheres

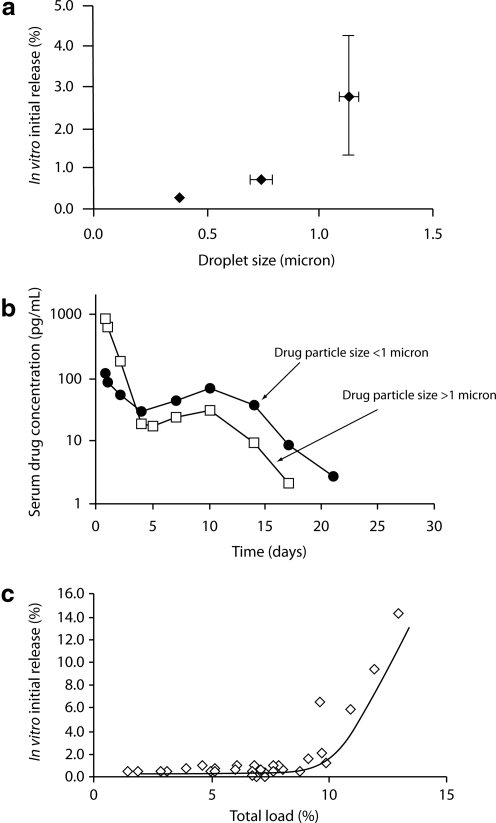

Manufacturing parameters have been identified that, when properly controlled, change the timing and pattern of drug release from PLG microspheres. At the drug level, release patterns can be modified via changes in drug particle size, drug load, and/or chemical modifications that affect the solubility or clearance properties of the liberated medication. For example, small drug particle sizes may be associated with low initial release rates for some medications (Fig. 2a). However, altering drug particle size may also affect the diffusion and erosion phases (Fig. 2b), demonstrating that changes in a single manufacturing parameter can affect multiple aspects of the drug release profile.

FIG. 2.

Control of initial release: (a and b) effect of drug particle size and (c) total load (drug+excipients) on release.

Excipient(s) can affect the porosity of the microspheres and/or alter the rate of polymer breakdown, either by modifying local pH conditions or by catalyzing ester hydrolysis. Another simple effect of excipients is demonstrated in Figure 2c. As shown, initial release increases quickly above a threshold total load, which is defined as including both drug and excipients. Thus, an increase in drug amount may need to be offset by a decrease in level of excipient to limit initial release, but this may impact other features of the release profile.

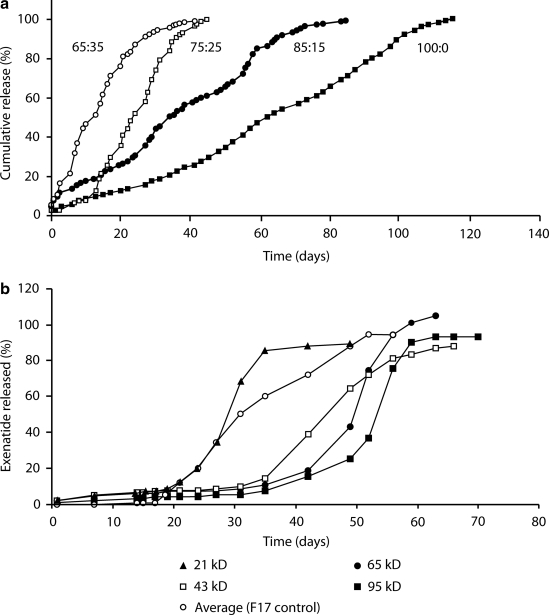

Finally, the PLG matrix can be modified to affect drug release. Increasing the ratio of lactide to glycolide in the matrix, for instance, decreases the overall hydrophilicity of the microspheres and thereby reduces their rate of biodegradation (Fig. 3a). Conversely, adding carboxylic end groups to the PLG polymers increases the hydrophilicity of the microspheres, favoring faster release. Increments or decrements in polymer molecular weight can reduce or increase, respectively, biodegradation rates (Fig. 3b).

FIG. 3.

Control of diffusion/erosion: (a) effect of lactide:glycolide ratio and (b) polymer molecular size on in vitro release.

Biological response to microspheres

A mild inflammatory “foreign body reaction” can occur in response to injected microspheres. In a prototypical reaction,22 polymorphonuclear leukocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and lymphocytes migrate to a foreign body. After several weeks, macrophages predominate and subsequently fuse to form foreign-body giant cells, which enclose the foreign-body reaction site, often in association with a fibrous capsule. In the case of microspheres, it is thought that the macrophages and giant cells contribute to biodegradation by engulfing the fragments as the microsphere polymer hydrolyzes.

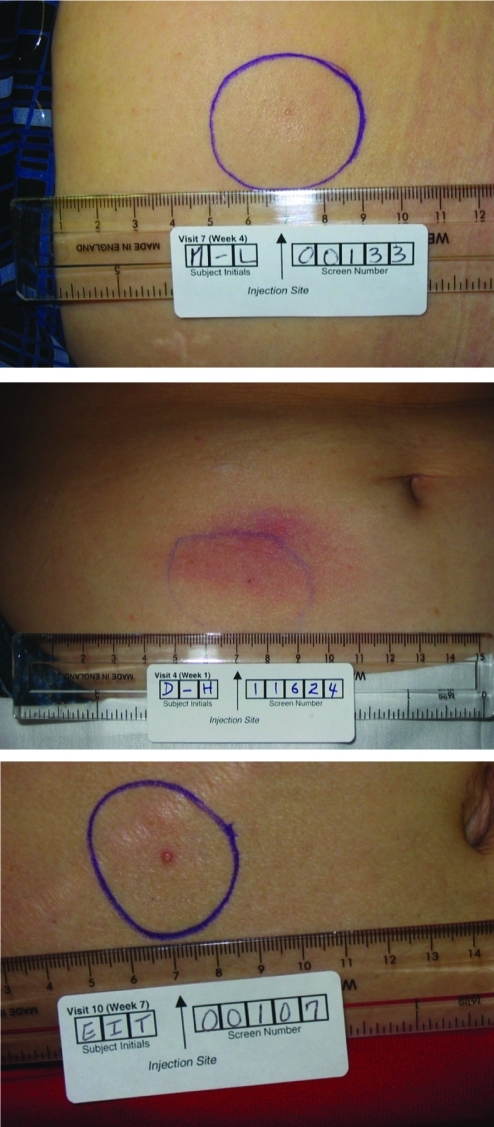

Because of the foreign body reaction, small nodules at the injection site may be observed after subcutaneous injection of drugs that use PLG microsphere technology.19 A typical nodule is a discrete, well-demarcated soft tissue mass or lump that is relatively firm (Fig. 4), although a softer surrounding swelling may occur early in its development. Nodule size depends on the quantity of administered microspheres, depth and volume of injection, and time after injection. In clinical trials, nodules were usually transient, typically resolving without medical intervention, and were therefore not recorded as adverse events unless symptoms were present, such as tenderness, pruritus, and/or erythema.

FIG. 4.

Examples of subcutaneous nodules observed after exenatide once-weekly injection in patients with type 2 diabetes.

EQW

EQW (2 mg s.c.) has been developed as a monotherapy as an adjunct to diet and exercise or as a combination therapy with another oral antidiabetes drug(s) in adults with type 2 diabetes. Several studies were required to develop the final EQW formulation (data on file, Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). In the first, both sucrose and mannitol were investigated as “pore formers” that would modulate release profiles and also act as stabilizers to maintain peptide integrity during manufacturing. However, mannitol, but not sucrose, was associated with excessive initial release, and sucrose was therefore used in all subsequent formulations. In a second study, ammonium sulfate was added in an effort to increase exenatide release during the lag phase. Although successful, the presence of ammonium sulfate also caused an undesired increase in initial release.

The optimal formulation, identified in the third study, resulted in extended release of exenatide at consistent therapeutic levels over the dosing interval, while also providing an acceptably low initial release. It contains encapsulated exenatide at a concentration of 5.0 mg per 100 mg of microspheres. The microspheres contain Medisorb 50:50 DL 4AP (Alkermes internal terminology) polymer, composed of lactide and glycolide monomers in a molar ratio of 50:50. The PLG polymer has a carboxylic end group and an inherent viscosity of approximately 0.4 dL/g. The only excipient in EQW is sucrose.

The EQW dosing kit includes everything required for patient self-administration: a vial of dry powder with a premeasured 2-mg dose of exenatide encapsulated in 40 mg of microspheres; a syringe prefilled with 0.65 mL of diluent; a vial connector; and needles for subcutaneous injection. To administer EQW, the patient connects the syringe to the vial via the vial connector, adds the diluent to the powder, shakes the mixture to ensure complete suspension, and injects the final solution subcutaneously into the abdomen, thigh, or back of the upper arm. EQW can be taken any time of day, with or without food, in contrast to EBID, which must be administered within 60 min before the two main meals of the day.7

Today, pen systems are often used for injectable diabetes medications like insulins.23 When compared with these therapies, administration of EQW requires a single additional step (i.e., suspension of the microspheres before administration). One study showed that a majority of patients were capable of independently self-administering a microsphere preparation: 88.3% of subjects with type 2 diabetes completed the fundamental steps necessary to prepare medication and deliver an injection with the EQW device (72.6% [n=74] completed the procedure without assistance, 15.7% [n=16] requested assistance by calling a simulated customer support line, and 11.8% [n=12] did not complete one or more of the fundamental steps).24

Pharmacokinetics

In one study,25 62 patients with type 2 diabetes were monitored for 12 weeks after a single administration of EQW at exenatide dosages of 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 7 mg, and 10 mg. The data demonstrated a multiphasic concentration–time profile consistent with the known mechanism of drug release from Medisorb microspheres. This included a very limited initial release phase (time of maximum plasma concentration during the first 48 h, 2.1–5.1 h) accounting for approximately 1–2% of the total area under the plasma concentration–time curve, followed by two additional phases corresponding to diffusion and erosion release with peak exenatide concentrations at approximately 2 and 7 weeks, respectively. Exenatide plasma concentrations were sustained for longer than 60 days postinjection for all doses. Plasma exenatide concentrations increased with increasing dose but were not strictly dose-proportional. The ratio of the maximum plasma concentration to the average plasma concentration was approximately 3 in all treatment groups, indicating a similar release profile over a fourfold dosage range.

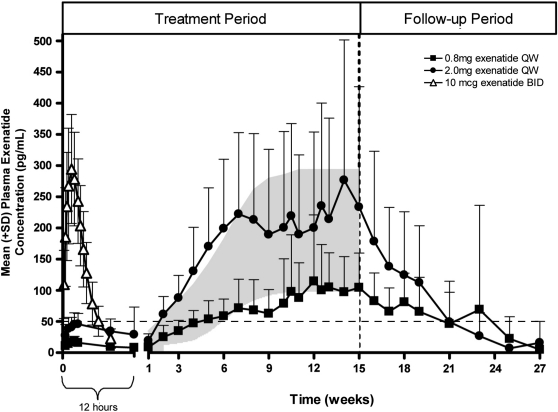

Nonparametric superpositioning of the single-dose data suggested that a 2-mg dose administered at weekly intervals would sustain an average steady-state exposure within the maximum plasma concentration (10th–90th percentile) range for EBID (211 [100, 385] pg/mL), which was considered a desirable therapeutic target.7,25 To test this prediction, 45 patients with type 2 diabetes were administered EQW once per week at dosages of 0.8 and 2.0 mg, and blood levels of exenatide were assessed over 15 weeks (Fig. 5).25 The subsequent concentration–time profiles demonstrated dosage-related increases in plasma exenatide concentrations that approached steady state after week 6–7. By week 2, plasma exenatide concentrations with the 2-mg dose exceeded the minimally effective level (approximately 50 pg/mL) shown to reduce fasting plasma glucose (FPG) concentrations;26 exenatide concentrations for the 2-mg dose remained within the target therapeutic range throughout the remainder of the treatment period.

FIG. 5.

Pharmacokinetics of exenatide once-weekly (QW), shown in plasma exenatide concentrations following a single dose of exenatide twice-daily (BID) (n=39) and multiple doses of exenatide QW (n=31). Shading represents exenatide blood level predictions for 2-mg (top boundary) and 0.8-mg (bottom boundary) weekly repeating exenatide QW administrations with the use of superpositioning of single-dose data. The vertical dashed line shows the end of the exenatide QW dosing period in the trial. The horizontal line is the minimally effective level of exenatide demonstrated to reduce fasting plasma glucose concentrations.26 Modified from Fineman et al.25 and reproduced with permission from Adis, a Wolters Kluwer business (© Adis Data Information BV 2011. All rights reserved).

Efficacy

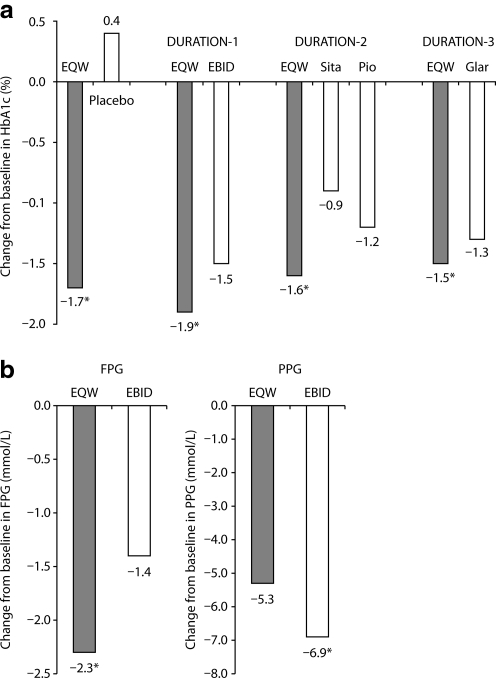

The most important test of any new formulation is its activity and safety during clinical use. The glucose-lowering efficacy of EQW has been reported in five published randomized clinical trials, including one placebo-controlled study27 and four comparative studies named Diabetes Therapy Utilization: Researching Changes in A1c, Weight and Other Factors Through Intervention with Exenatide ONce Weekly (DURATION-1, -2, -3, and -5),28–33 all of which demonstrated improved glycemic control with EQW (Table 1 and Fig. 6a). Other DURATION trials have been described in press releases (DURATION-4 and DURATION-6).34,35 Results from the latter trials have been consistent with the earlier DURATION studies.

Table 1.

Design, Efficacy, and Select Adverse Events for Published DURATION Studies

| DURATION-1 | DURATION-2 | DURATION-3 | DURATION-5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | OL | DBDD | OL | OL |

| Duration (weeks) | 30 | 26 | 26 | 24 |

| Background therapy | D/E alone or with Met, SU, or TZD (or combinations) | Met | Met±SU | D/E alone or with Met, SU, or TZD (or combinations) |

| EQW | 2 mg QW | 2 mg QW | 2 mg QW | 2 mg QW |

| Comparator(s) | EBID (10 μg BID) | Sit (100 mg QD) | Insulin glargine (10 IU QD)a | EBID (10 μg BID) |

| Pio (45 mg QD) | ||||

| ITT population (n) | 148 | 160 | 233 | 129 |

| Withdrawal (%) | 13.5% | 20.6% | 10.3% | 15.5% |

| HbA1c (%) | ||||

| Baseline | 8.3 | 8.6 | 8.3 | 8.5 |

| LS mean change | −1.9 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −1.6 |

| HbA1c targets (%) | ||||

| <7.0% | 71 | 59 | 60 | 58 |

| ≤6.5% | 45 | 39 | 35 | 41 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | ||||

| Baseline | 9.60 | 9.21 | 9.82 | 9.60 |

| LS mean change | −2.33 | −1.78 | −2.11 | −1.94 |

| Weight (kg) | ||||

| Baseline | 101.7 | 89.9 | 91.2 | 97 |

| LS mean change | −3.7 | −2.3 | −2.6 | −2.3 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | ||||

| Baseline | 127.8 | 126.4 | 135.4 | 130.4 |

| LS mean change | −4.7 | −3.6 | −3.0 | −2.9 |

| Adverse events (%) | ||||

| Nausea | 26.4 | 23.8 | 12.9 | 14.0 |

| Diarrhea | 14.9 | 18.1 | 8.6 | 9.3 |

| Vomiting | 10.8 | 11.3 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| Constipation | 10.8 | 5.6 | 3.0 | 0.8 |

| Injection site pruritus | 18.2 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 4.7 |

| Injection site erythema | 7.4 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 5.4 |

Adjusted to target fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of 4.0–5.5 mmol/L.

BID, twice-daily; DBDD, double-blind double-dummy; D/E, diet and exercise; EBID, exenatide BID; EQW, exenatide once-weekly; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; ITT, intent to treat; LS, least square; Met, metformin; OL, open-label; Pio, pioglitazone; QD, once-daily; QW, once-weekly; SBP, systolic blood pressure; Sit, sitagliptin; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

FIG. 6.

Glucose control mediated by exenatide once-weekly (EQW). (a) Change from baseline in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in the placebo-controlled trial (Kim et al.27) and DURATION-1, -2, and -3.28,30,31 (b) Change from baseline in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and postprandial plasma glucose (PPG) in DURATION-1.28 EBID, exenatide twice-daily; Glar, insulin glargine; Pio, pioglitazone; Sita, sitagliptin. *P<0.05 versus comparators.

The results of DURATION-1 demonstrated the similarities and differences between the clinical activities of exenatide when administered in microsphere form (EQW) or by itself (EBID). The trial was an open-label non-inferiority study in which 148 subjects received EQW and 147 received EBID.28 Eligible patients had type 2 diabetes, a mean HbA1c of 8.3%, and a diabetes duration of 6–7 years and were treated with diet modification and exercise alone or with one or more oral glucose-lowering medications (metformin, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones). After 30 weeks of therapy, patients on EQW had a greater mean reduction from baseline in HbA1c (Fig. 6a) and a higher proportion reaching target HbA1c ≤7% (77% vs. 61%, P=0.0039) than did those on EBID. At study end point, 96% of patients treated with EQW and 90% treated with EBID demonstrated reductions in HbA1c. Body weight decreased progressively in both treatment groups, with similar decrements at week 30 (−3.7 kg vs. −3.6 kg, P=0.89). More than 75% of patients in both treatment groups lost weight. Similar mean reductions from baseline in fasting triglycerides (−15% vs. −11%) and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (−4.7 mm Hg vs. −3.4 mm Hg and −1.7 mm Hg vs. −1.7 mm Hg, respectively) were observed for EQW and EBID, respectively.

Both EQW and EBID reduced FPG and postprandial plasma glucose (PPG) from baseline values. However, the overall reduction in FPG was significantly greater for EQW than it was for EBID, whereas change from baseline in 2-h PPG after a meal tolerance test was significantly greater for EBID than it was for EQW (Fig. 6b). These results are consistent with the pharmacokinetic properties of the two formulations. The activity of EBID is highest 2 h after mealtime administration,7 when the PPG measurements were performed, but is relatively low 10–12 h later, when the FPG assessments occurred. By comparison, EQW levels are maintained continuously throughout the day.

Efficacy differences between EQW and EBID were confirmed in a DURATION-1 extension study,29 in which 128 patients on EQW remained on EQW for an additional 22 weeks (52 weeks total treatment), whereas 130 patients on EBID switched to EQW. Patients continuing on EQW maintained HbA1c reductions, whereas patients switching from EBID to EQW achieved further reductions in HbA1c, so that both treatment groups had mean HbA1c levels of 6.6% at week 52. The conclusions from DURATION-1 were further confirmed in DURATION-5, a second trial with a similar design that compared the safety and efficacy profiles of EQW and EBID (Table 1).32

Safety and tolerability

Withdrawal rates due to an adverse event were relatively low in the placebo-controlled27 and DURATION28–33 studies, demonstrating an overall favorable tolerability profile for EQW. Most adverse events were similar for EQW and EBID. Hypoglycemic episodes were rare in patients on either therapy,28 although hypoglycemia can be seen more commonly with concomitant sulfonylurea therapy, and the most common tolerability issue was gastrointestinal upset. However, in DURATION-1, patients exhibited greater tolerance for the once-weekly formulation than they did for the twice-daily formulation;28 thus, the incidence of nausea was reduced (26.4% vs. 34.5% for EQW vs. EBID, P<0.05), as was the incidence of vomiting (10.8% vs. 18.6% for EQW vs. EBID) and discontinuation rates due to gastrointestinal adverse events (3% vs. 5% for EQW vs. EBID). For EQW, reported events of nausea occurred predominantly during treatment initiation in the first 6–8 weeks of therapy. In general, the adverse event profile in DURATION-1 was similar to that observed in DURATION-5.32 Gradual dose escalation of exenatide has been shown to reduce nausea and vomiting,36 and the greater gastrointestinal tolerability of EQW relative to EBID in both DURATION-1 and -5 may reflect the more gradual approach of EQW to steady state.25

In the placebo-controlled study, injection site nodules associated with EQW were reported by 80% of patients (Table 2) (Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., data on file). Informal communication from DURATION-1 study staff indicated that nodules were generally 0.5–0.75 cm in diameter, and their incidence seemed to decline over time, even in patients with numerous earlier episodes. Some nodules were observed by palpation, whereas others were visible (Fig. 4). Nodules resolved unremarkably in DURATION-1 in all but two patients, who experienced delayed resolution. One of these patients withdrew.

Table 2.

Skin Nodules and Injection Site-Related Adverse Events Associated with Exenatide Once-Weekly Injections

| EQW | Placebo* | |

|---|---|---|

| Skin nodules (placebo-controlled)† | ||

| Subjects (n) | 15 | 13 |

| Subjects with ≥1 palpable nodules [n (%)] | 12 (80) | 7 (53.8) |

| Injections associated with nodule (%) | 83.0 | 42.9 |

| Subjects with ≥1 nodule- associated AE [n (%)]‡ | 1 (6.7) | 2 (15.4) |

| Mean time to first detection (days) | 28 | 28 |

| Mean duration of nodules (days) | 31.7 | 20.7 |

| Injection site-related adverse events over 30 weeks (DURATION-1)† | ||

| Total injections (n) | 4,161 | — |

| Pruritus or urticaria [n (% injections)] | 200 (4.8) | — |

| Pruritus [n (% patients)] | 26 (17.6) | |

| Irritation, burning, or pain [n (%)] | 58 (1.4) | — |

| Erythema [n (%)] | 37 (0.9) | — |

Data shown are from those on file at Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Microspheres without exenatide.

The placebo-controlled study and DURATION-1 had treatment phases of 15 and 30 weeks, respectively.

Nodules were not considered adverse events (AEs) unless accompanied by prolonged pain, induration, redness, bleeding, or inflammation.37

EQW, exenatide once weekly.

The rate of nodule-associated adverse events (i.e., accompanied by prolonged pain, induration, redness, bleeding, or inflammation) was low in the placebo-controlled trial (6.7%; Table 2) and in DURATION-1 (0.7%). Other injection site adverse events in DURATION-1 were generally mild in intensity and relatively rare (Table 2), and most resolved within a month. The most common was injection site pruritus, although its rate appeared to wane over time from 11.0% between weeks 4 and 6 to 4.6% between weeks 28 and 30.

In DURATION-1, antibody titers were higher with EQW than EBID (P=0.0002).28 In the DURATION-1 extension study, antibody titer to exenatide peaked at week 6 for both treatment groups (geometric mean antibody titer±SE, 33.2±8.2 for patients who had received EQW exclusively and 12.6±3.4 for patients who had switched from EBID to EQW) but decreased over time as occurs in most patients who develop antibodies to exenatide.29 At week 52, geometric mean antibody titers to exenatide were 12.8±3.4 in the group treated with EQW only. In the small percentage of patients with higher antibody titers to exenatide (∼5%), a wide range of HbA1c response was observed, with the mean effect being a robust, albeit somewhat attenuated, reduction in HbA1c compared with those with lower antibody titers. Patients who developed antibodies to exenatide tended to have more injection site reactions, such as redness or itching. No immune-mediated respiratory symptoms or anaphylactic reactions were reported with EQW.

Conclusions

A long-acting formulation of exenatide has been developed for once-weekly administration by encapsulating exenatide in microspheres of the biodegradable polymer PLG. Although this formulation is new, exenatide and PLG encapsulation have been used clinically for >5 and >25 years, respectively.7,18 EQW provides constant exposure to exenatide following once-weekly, patient-administered, subcutaneous injections. Like EBID, EQW has been show to reduce HbA1c, improve fasting glucose, and reduce body weight.28,29,32 Advantages of EBID over EQW include modestly better postprandial control for the two postinjection meals, no resuspension step before injection, and fewer injection site adverse events. Advantages of EQW over EBID include a greater ability to meet therapeutic HbA1c goals, better fasting glucose control, a lower incidence of gastrointestinal upset, more flexible dosing, and less frequent injections (one vs. 14 per week).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Norris, Ph.D., of Ecosse Medical Communications (Princeton, NJ) for editorial assistance provided during the preparation of this manuscript and Stephen Flores for helpful discussion. Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Eli Lilly & Co. provided funding for this study.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.B.DeY. and L.M. are employees and stockholders of Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. V.Sa. and M.T. are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly & Co. P.H. is an employee and stockholder of Alkermes, Inc.

References

- 1.Lovshin JA. Drucker DJ. Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:262–269. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norris SL. Lee N. Thakurta S. Chan BK. Exenatide efficacy and safety: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2009;26:837–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gentilella R. Bianchi C. Rossi A. Rotella CM. Exenatide: a review from pharmacology to clinical practice. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:544–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montanya E. Sesti G. A review of efficacy and safety data regarding the use of liraglutide, a once-daily human glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue, in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2009;31:2472–2488. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drab SR. Clinical studies of liraglutide, a novel, once-daily human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog for improved management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:43S–54S. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.pt2.43S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madsbad S. Kielgast U. Asmar M. Deacon C. Torekov SS. Holst JJ. An overview of once-weekly GLP-1 receptor agonists—available efficacy and safety data and perspectives for the future. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:394–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.San Diego, CA: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2009. Byetta [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mudaliar S. Henry RR. Incretin therapies: effects beyond glycemic control. Am J Med. 2009;122(6 Suppl):S25–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Roche Announces Amendment of the Trial Protocols for the Taspoglutide Phase III Programme. www.roche.com/investors/ir_update/inv-update-2010-06-18b.htm. [May 25;2011 ]. www.roche.com/investors/ir_update/inv-update-2010-06-18b.htm

- 10.Torsoli A. Roche Said to Return Diabetes Drug Rights to Ipsen. www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-02-01/roche-said-to-return-taspoglutide-diabetes-drug-rights-amid-patient-trials.html. [May 25;2011 ]. www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-02-01/roche-said-to-return-taspoglutide-diabetes-drug-rights-amid-patient-trials.html

- 11.Fagiolini A. Casamassima F. Mostacciuolo W. Forgione R. Goracci A. Goldstein BI. Risperidone long-acting injection as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1727–1740. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2010.490831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deeks ED. Risperidone long-acting injection: in bipolar I disorder. Drugs. 2010;70:1001–1012. doi: 10.2165/11204480-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moller HJ. Long-acting injectable risperidone for the treatment of schizophrenia: clinical perspectives. Drugs. 2007;67:1541–1566. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swainston Harrison T. Plosker GL. Keam SJ. Extended-release intramuscular naltrexone. Drugs. 2006;66:1741–1751. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666130-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mannelli P. Peindl K. Masand PS. Patkar AA. Long-acting injectable naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:1265–1277. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.; 2009. Sandostatin LAR Depot [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Titusville, NJ: Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2010: Risperdal CONSTA [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waltham, MA: Alkermes, Inc.; 2010. Vivitrol [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson JM. Shive MS. Biodegradation and biocompatibility of PLA and PLGA microspheres. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;28:5–24. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis DH. Controlled release of bioactive agents from lactide/glycolide polymers. In: Chasin M, editor; Langer RS, editor. Biodegradable Polymers as Drug Delivery Systems. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1990. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overview Emergence of Suture Materials. www.sutures-bbraun.com/index.cfm?BA9BA32D2A5AE6266471269F12FB4F8C. [Dec 28;2010 ]. www.sutures-bbraun.com/index.cfm?BA9BA32D2A5AE6266471269F12FB4F8C

- 22.Anderson JM. Rodriguez A. Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunbar JM. Madden PM. Gleeson DT. Fiad TM. McKenna TJ. Premixed insulin preparations in pen syringes maintain glycemic control and are preferred by patients. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:874–878. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.8.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenzi G. Schreiner B. Osther J. Boardman M. Application of adult-learning principles to patient instructions: a usability study for an exenatide once-weekly injection device. Clin Diabetes. 2010;28:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fineman M. Flanagan S. Taylor K. Aisporna M. Shen LZ. Mace KF. Walsh B. Diamant M. Cirincione B. Kothare P. Li WI. MacConell L. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of exenatide extended-release after single and multiple dosing. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50:65–74. doi: 10.2165/11585880-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor K. Kim D. Nielsen LL. Aisporna M. Baron AD. Fineman MS. Day-long subcutaneous infusion of exenatide lowers glycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 2005;37:627–632. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim D. MacConell L. Zhuang D. Kothare PA. Trautmann M. Fineman M. Taylor K. Effects of once-weekly dosing of a long-acting release formulation of exenatide on glucose control and body weight in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1487–1493. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drucker DJ. Buse JB. Taylor K. Kendall DM. Trautmann M. Zhuang D. Porter L. DURATION-1 Study Group: Exenatide once weekly versus twice daily for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2008;372:1240–1250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buse JB. Drucker DJ. Taylor KL. Kim T. Walsh B. Hu H. Wilhelm K. Trautmann M. Shen LZ. Porter LE. DURATION-1 Study Group: DURATION-1: exenatide once weekly produces sustained glycemic control and weight loss over 52 weeks. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1255–1261. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergenstal RM. Wysham C. Macconell L. Malloy J. Walsh B. Yan P. Wilhelm K. Malone J. Porter LE. DURATION-2 Study Group: Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus sitagliptin or pioglitazone as an adjunct to metformin for treatment of type 2 diabetes (DURATION-2): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:431–439. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamant M. Van Gaal L. Stranks S. Northrup J. Cao D. Taylor K. Trautmann M. Once weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-3): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375:2234–2243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60406-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blevins T. Pullman J. Malloy J. Yan P. Taylor K. Schulteis C. Trautmann M. Porter L. DURATION-5: exenatide once weekly resulted in greater improvements in glycemic control compared with exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1301–1310. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wysham C. Bergenstal R. Malloy J. Yan P. Walsh B. Malone J. Taylor K. DURATION-2: efficacy and safety of switching from maximum daily sitagliptin or pioglitazone to once-weekly exenatide. Diabet Med. 2011;28:705–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amylin Pharmaceuticals I. DURATION-4 Study Results: BYDUREON Efficacy and Tolerability Profile Extended to Monotherapy Treatment. investors.amylin.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=101911&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1438147&highlight= [Dec 20;2010 ]. investors.amylin.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=101911&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1438147&highlight=

- 35.Amylin Pharmaceuticals I. DURATION-6 Top-Line Study Results Announced. investors.amylin.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=101911&p=irol-newsArticle&id=1535419. [May 10;2011 ]. investors.amylin.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=101911&p=irol-newsArticle&id=1535419

- 36.Fineman MS. Shen LZ. Taylor K. Kim DD. Baron AD. Effectiveness of progressive dose-escalation of exenatide (exendin-4) in reducing dose-limiting side effects in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2004;20:411–417. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothstein E. Kohl KS. Ball L. Halperin SA. Halsey N. Hammer SJ. Heath PT. Hennig R. Kleppinger C. Labadie J. Varricchio F. Vermeer P. Walop W. Brighton Collaboration Local Reaction Working Group: Nodule at injection site as an adverse event following immunization: case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation. Vaccine. 2004;22:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]