Abstract

It has been debated whether human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and embryonic stem cells (ESCs) express distinctive transcriptomes. By using the method of weighted gene co-expression network analysis, we showed here that iPSCs exhibit altered functional modules compared with ESCs. Notably, iPSCs and ESCs differentially express 17 modules that primarily function in transcription, metabolism, development, and immune response. These module activations (up- and downregulation) are highly conserved in a variety of iPSCs, and genes in each module are coherently co-expressed. Furthermore, the activation levels of these modular genes can be used as quantitative variables to discriminate iPSCs and ESCs with high accuracy (96%). Thus, differential activations of these functional modules are the conserved features distinguishing iPSCs from ESCs. Strikingly, the overall activation level of these modules is inversely correlated with the DNA methylation level, suggesting that DNA methylation may be one mechanism regulating the module differences. Overall, we conclude that human iPSCs and ESCs exhibit distinct gene expression networks, which are likely associated with different epigenetic reprogramming events during the derivation of iPSCs and ESCs.

Introduction

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) produced from somatic cells by overexpressing key transcription factors closely resemble embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in many aspects, including cell morphology, chromatin modifications, and differentiation potency [1–6]. Human iPSCs have become a powerful tool for biomedical research and may provide a promising alternative for cell-replacement therapies [7–9]. However, regardless of parental cell lineages or reprogramming techniques, several studies have shown that iPSCs are different from ESCs at the level of RNA transcription, leading to a debate regarding whether iPSCs are truly similar to ESCs [10–14].

It is suggested that transcriptome changes between human ESCs and iPSCs arise from different culture conditions or different laboratory practices [1–2,10–12]. This hypothesis is supported by cluster analysis of gene expression profiling from different research groups [11,12], in which iPSCs and ESCs derived from individual research labs tend to be clustered together into a lab-specific pattern [11,12]. However, these analyses simply merged gene expression data generated from different labs without removing batch effects, which may significantly mislead the conclusions derived from independently measured microarray data [15]. These lab-specific gene expression patterns between iPSCs and ESCs may need more thorough re-examination.

Several studies have attempted to identify individual genes differentially expressed between iPSCs and ESCs. One study reported a total of 294 differentially expressed genes between human iPSCs and ESCs, suggesting that iPSCs have a unique expression signature [13]. However, these 294 individual gene signatures are not conserved in different iPSCs after independently re-examining the same database by several groups [11,12,14]. This suggests that unique and reliable gene expression signatures distinguishing iPSCs and ESCs still remain elusive.

In contrast to individual gene expression signatures that are less conserved in various iPSCs as discussed above, certain functional groups have been consistently found to be altered between ESCs and iPSCs [16,17]. For example, functional groups involved in development, transcription, immune response, and enzyme activities for metabolism have been frequently found in recent studies [16,17]. Functional groups (modules) are believed to be stable units in systems biology because the overall function of a module can remain the same, whereas individual gene expression can be changed or replaced by other genes with similar redundant functions. Potentially, functional modules can more effectively reveal consistent differences between iPSCs and ESCs than individual gene signatures.

Here, we utilized a systems biology method, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), to analyze a large set of genome-wide gene expression profiles of typical human iPSCs and ESCs. Our analysis revealed that iPSCs are inherently different from ESCs at the module level. In particular, we identified 17 functional modules primarily functioning in transcription, development, immune response, and metabolism that distinguish iPSCs from ESCs. We further demonstrated that differentially expressed functional modules are associated with different DNA methylation profiles between human iPSCs and ESCs.

Materials and Methods

Microarray data

Microarray data for iPSCs and ESCs were gathered from previously published data deposited in GEO (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The collected database includes data of various iPSCs such as those derived from different sets of gene combinations and different cells, even different species, human and mouse. Concerning the well-known data variations derived from different microarray platform, we focused on data generated by Affymetrix platform. However, for validation, we also include one set of data from Illumina microarray platform. The following data sets were extracted, including human genome U133 Plus 2.0 array, GSE12390, GSE14711, GSE15176 GSE15148, GSE16093, GSE16654, and GSE9865; Affymetrix Mouse Genome Array, GSE 14012, GSE10806, GSE10871, and GSE15267; and Illumina, GSE16062. Three new available datasets were also included: GSE27280, GSE26455, and GSE23583.

DNA methylation profiling with Illumina Infinium assays

Human Methylation DNA Analysis BeadChip from Illumina, Inc. (San Diego, CA), was used to interrogate 26,837 highly informative CpG sites over 14,152 genes for 10 samples, 5 iPSCs (hNPC8iPS, hNPC9iPS, hNPC10iPS, CCD1079iPS, and IMR90iPS), and 5 ESCs (HSF6, H1, H9, HSF1, and Hues7). The experiment was performed following procedures based on the manufacturer's instructions, including bisulfite conversion of genomic DNAs, hybridization, and extraction of raw hybridization signals. BeadStudio software from Illumina, Inc., was used to analyze the methylation data.

Gene expression data analysis

The microarray data were analyzed using R (www.r-project.org/), the preliminary array quality assessment with affyQCReport package, the background adjustment and normalization with affy package, and the gene expression values estimation with limma package. Because these microarray data were generated by different research groups, the batch effect should be filtered out before combining these microarray datasets. An algorithm called ComBat [15], which runs in R environment and uses parametric and nonparametric empirical Bayes frameworks to adjust microarray data for batch effects, was used to adjust the final gene expression values for all datasets.

After filtering the outlier chips by the preprocessing function from our network software, WGCNA [18], we had a total of 47 chips for network analysis: 34 iPSCs and 13 ESCs. These 34 remaining iPSCs samples were generated by the most stringent methods and their biological properties close to human ESCs.

Network construction and module identification

The network was constructed by using WGCNA as we previously described [18]. Briefly, WGCNA measure any gene pair (i,j) similarity Sij as defined below [19–22].

|

where xi and xj as the gene expression of genes i and j across multiple microarray samples.

The similarity was measured continuously with a power β as a weight to obtain the weighted adjacency αi,j for any gene pair as

|

where β can be chosen using the scale-free topology criterion. Since log(aij)=β×log(sij), the overall network adjacency is linearly correlated with the co-expression similarity on a logarithmic scale. The adjacency matrix A=[αi,j] constructs a weighted network.

The network modules are defined as cluster branches derived from hierarchical clustering based on the network proximity as input. The proximity is defined by the topological overlap measure [18,20–22] of connection strengths of all possible gene pairs collected in the adjacency matrix A described above.

The network and module membership

The network membership is measured by the network eigengene based connectivity, Ki [23–26]

|

where xi is the expression profile of the gene i and E is the eigengene of the network as defined below.

|

where V1 is the singular vector in V below corresponding to the largest absolute singular value in D below

|

where X is the n×m matrix of standardized expression profiles of the n genes in the network/network-module across m samples, U is an n×m matrix with orthogonal columns, D is an m×m diagonal matrix of singular values, and V is an m×m orthogonal matrix of singular vectors.

Key node identification

The connectivity considers both the network topology and the eigengene-based connectivity as our previously reported [26,27] and as defined below.

|

where di represents the ith node degree that measures the total connectivity of the ith node, and dmax represents the maximum degree of a node in the network. |Cor(xi, E)| is the absolute value of Pearson correlation coefficient, where xi is a vector of gene expression of ith node, and E eigengene of the network. We put twice weight on eigengene-based connectivity because our network is highly connected in topology and our data showed almost equal importance on first and second components.

Support vector machines

Support vector machines (SVMs) [28] are a set of related machine learning methods for classifying datasets based on hyperplanes in a high or infinite dimensional space in which samples of a cluster can be separated with the largest distance to others. The R package e1071 was used to train our datasets and predict the accuracy of module-based separations in this study. We used 70% samples as training set, and the rest (30%) as test data. The accuracy was calculated by measuring both average percentage and kappa value (a value for measuring agreement) after randomly sampling 3,000 times for each module combination. The module combination starts with 1 module to 2 modules, 3 modules until 17 modules in 17 module set (Table 1, Fig. 3C), and begins from 1 module to 2 modules, until 4 modules in 4 super-module set (Fig. 3D).

Table 1.

Total 17 Modules Differently Expressed in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Embryonic Stem Cells

| Module no. | Module color | P_value | Nodes | Annotation | IPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Blue | 2.50E-28 | 110 | Gene expression and RNA metabolism | Down |

| 11 | Lightyellow | 4.12E-21 | 13 | RNA binding/lysosomal lumen acidification | Down |

| 8 | Grey | 4.01E-20 | 30 | ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process, glycine dehydrogenase (decarboxylating) activity | Down |

| 3 | Brown | 8.50E-20 | 99 | transferase activity, signaling transduction | Down |

| 9 | Lightcyan | 1.67E-18 | 15 | catalytic activity/nucleoside triphosphate adenylate kinase activity | Down |

| 10 | Lightgreen | 8.91E-16 | 14 | peptide antigen-transporting ATPase activity | Down |

| 7 | Greenyellow | 3.74E-15 | 37 | glutathione transferase activity, myeloid progenitor cell differentiation | Down |

| 16 | Turquoise | 1.82E-13 | 163 | DNA repair, transcription | Down |

| 12 | Midnightblue | 2.95E-13 | 15 | acetyltransferase activity, enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase activity | Down |

| 6 | Green | 3.72E-13 | 40 | cGMP-stimulated cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity, negative regulation of lymphocyte differentiation | Down |

| 4 | Cyan | 1.68E-24 | 32 | RNA splicing, vitamin B6 metabolic process | Up |

| 15 | Tan | 2.88E-21 | 22 | acute inflammatory response/membrane organization and biogenesis | Up |

| 13 | Pink | 4.68E-17 | 30 | regulation of cell growth | Up |

| 17 | Yellow | 9.04E-17 | 41 | Cell surface/regulation of developmental process | Up |

| 1 | Black | 1.04E-14 | 57 | mediator complex/regulation of adenosine receptor signaling pathway | Up |

| 14 | Salmon | 1.19E-14 | 20 | glycoprotein-N-acetylgalactosamine-3-beta-galactosyltransferase activity | Up |

| 5 | Darkred | 6.99E-13 | 12 | catalytic activity, single-stranded DNA specific endodeoxyribonuclease activity | Up |

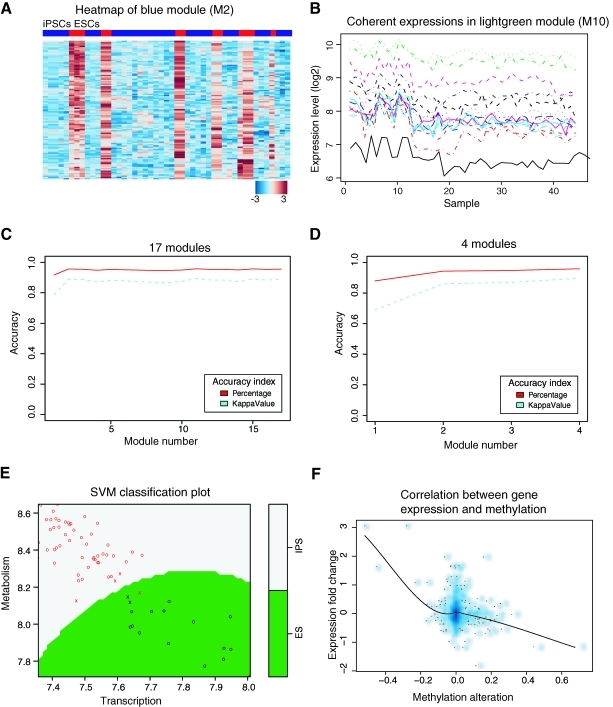

FIG. 3.

Differential activations of functional modules in iPSCs and ESCs are inversely correlated with DNA methylation and can be used for annotation of iPSCs and ESCs. (A) We use the heatmap of M2, blue module (Table 1) as an example to show gene co-expression in iPSCs (blue) and ESCs (red). In the heatmap, each row represents a gene, and each column denotes a sample. Red and blue represent up- and downregulated genes, respectively. (B) Gene expression in a module is all differentially regulated in the same pattern across all observed conditions (ie, coherently expressed). (C–E) Predictive model using SVMs. Accuracy represents the mean of 3,000 random samplings for every possible module permutation with sample size from 1 to 17 modules (C) or 1 to 4 meta-modules (D). (E) SVM plot visualizing the classification of iPSCs and ESCs based on 2 meta-modules, transcription and metabolism. “X” denotes support vectors and “O” with corresponding color represents classified true groups (iPSCs/ESCs). The colored background visualizes the predicted group regions. (F) Density dot plot showing overall inverse correlation between gene expressions and DNA methylation based on all genes in total 17 modules. Darker blue indicates higher density of genes. SVMs, support vector machines. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

Results

Human iPSCs and ESCs exhibit distinctive transcriptional profiles

Recent studies reported that distinctive iPSC expression profiles are lab-specific patterns [11,12]. However, these analyses did not take into account of experimental batch effects that may confound the conclusions. To determine if these profiling are intrinsic properties in various iPSCs or random across different conditions, we analyzed available iPSC and ESC gene expression datasets deposited in the GEO database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) [7,29–31] (Materials and Methods section). These datasets include data of various iPSCs resources such as virus-integrating-iPSCs, vector-free iPSCs, and protein-directed reprogramming iPSCs (Materials and Methods section). These iPSCs generated by stringent methods are well characterized and show similar biological properties to human ESCs [7,30]. To compare all collected gene expression datasets generated from different labs, we first filtered potential outliers based on low inter-array correlation, followed by global normalization, and finally batch effect removal (Materials and Methods section). Therefore, the different gene expression patterns expressed between these iPSCs and ESCs should represent typical profiling variations between iPSCs and ESCs.

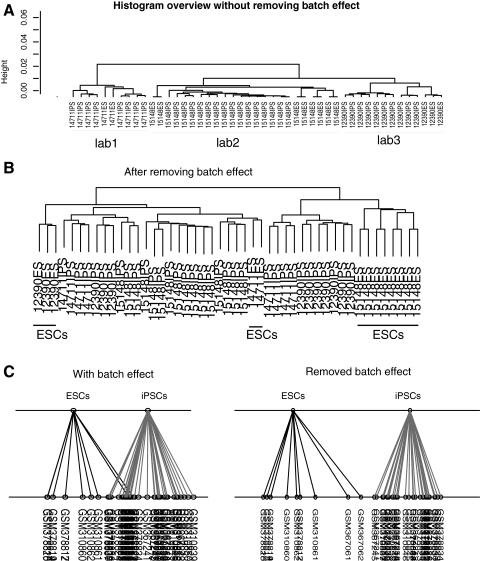

Without removing batch effects, cluster analysis of these expression data shows lab-specific groupings (Fig. 1A) as previously reported; however, the same analysis with removed batch effects revealed cell-type-specific profiling (Fig. 1B). In other words, ESCs are mostly separated from iPSCs regardless of lab origin; only 2 ESC samples were misgrouped (Fig. 1B). To determine whether the misgrouped samples were caused by computational limitations of cluster analysis, we applied between-group analysis, a high sensitivity multivariate analysis [32], to discriminate the samples. Consistently, between-group analysis of the same samples revealed 2 clearly separated groups after batch effect removal (Fig. 1C, right panel). This indicated that batch effects caused the lab-specific groupings, and that iPSCs indeed show distinct gene expression profiles compared with ESCs.

FIG. 1.

Human iPSCs express distinctive transcriptomes compared with ESCs. Typical iPSCs and ESCs gene expression profiles were analyzed by both cluster analysis and between-group. Lab-specific patterns were gone after removing batch effects. Cluster analysis (A, B) of samples before (A) and after (B) removing batch effects. (C) Between-group analysis of same samples and before (left panel) and after (right panel) removing batch effects. Samples were labeled by GEO deposited number. iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; ESCs, embryonic stem cells.

Gene networks are differentially expressed in iPSCs and ESCs

Because individual gene signatures distinguishing iPSCs and ESCs could not be extracted [11,12], we turned to gene network analysis to examine consistent functional module differences between iPSCs and ESCs by employing WGCNA [18] (see Materials and Methods section).

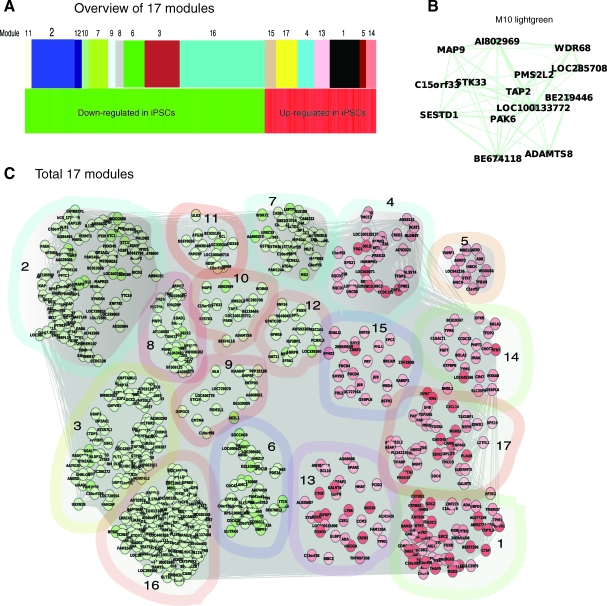

WGCNA analysis of the differentially expressed genes (Materials and Methods) produced a network significantly altered between iPSCs and ESCs (Fig. 2, P<3.505E-08). This network contains 751 nodes (genes), 79,159 edges (interactions), and 17 primary modules (Fig. 2A–C, Table 1). Of note, 10 out of 17 modules (537 genes) were downregulated, whereas only 214 genes distributed in 7 modules were overexpressed in iPSCs (Table 1). Based on Gene Ontology (GO, www.geneontology.org), these modules primarily function in transcription (M2, M11, M12, and M16), development (M6, M7, M13, and M17), immune response (M15), metabolism (M4, M5, and M14), and enzyme activities for broad bioprocesses primarily including metabolism (M3, M8, M9, M10) (Table 1). We thereafter refer these primary functional modules as meta-modules (transcription, development, immune response, and metabolism).

FIG. 2.

Gene networks are differentially expressed in human iPSCs and ESCs. (A) An overview of 17 network modules identified by weighted gene co-expression network analysis (Table 1 for detail). (B) An example of a module (light green) shows network component connections. Node color denotes differential expression level (iPSCs/ES), green for downregulation, and red for upregulation. Node size represents the importance of a node; bigger size indicates more importance. Edge denotes interaction strength, thicker for stronger interactions. (C) A holistic view of all 17 modules. Ten and 7 out of total 17 modules are downregulated (green nodes) and upregulated (red nodes) in iPSCs, respectively. The same illustration strategy was used in all network figures in this study. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

Genes of network modules are coherently co-expressed and can be used as variables to distinguish iPSCs from ESCs

Genes in our 17 identified differentially expressed modules are consistently co-expressed (Fig. 3A) and coherent (Fig. 3B). To determine whether these modules can be used as variables to distinguish iPSCs and ESCs, we added 3 independent datasets (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd; Materials and Methods section) and quantified these modules by calculating the module eigengene (see definition in Materials and Methods section). The quantitative values were used to train discriminative models and to predict the accuracy of our models in discriminating iPSCs from ESCs. SVMs [28] were employed here for classifying samples and the accuracy was measured by calculating both correct proportion and kappa value (Materials and Methods section). Based on the 17 modules (Table 1, Fig. 1) and 4 meta-modules (transcription, metabolism, immune response, and development), we used re-iterative random sampling (of 3,000 times) on 70% samples as training set and the rest as testing dataset, and found that the overall accuracy reached 96% (kappa 0.90) and 95.9% (kappa 0.90), respectively (Fig. 3C, D). Even with 2 meta-modules, transcription and metabolism, iPSCs and ESCs can be classified with an accuracy of 94% (kappa 0.85) (Fig. 3E). This indicated that the modules identified in this study can be used as quantitative variables to discriminate these 2 cell types.

The expression level of modular genes is inversely correlated with DNA methylation

To explore the mechanisms underlying the functional module differences between iPSCs and ESCs, we compared genome-wide DNA methylation profiling of iPSCs and ESCs by performing an independent microarray experiment on 5 iPSCs and 5 ESCs (Materials and Methods section). If DNA methylation plays a role in regulating gene expression, we expect genes with lower expressions to have higher levels of methylation at their promoters. After correlating methylation profiles with gene expression data used for building the network (751 genes total), we found an overall inverse correlation between gene expression and DNA methylation in the network (Fig. 3F). However, a large fraction of genes do not show methylation changes (middle in Fig. 3F), indicating that DNA methylation only partially accounts for the gene expression differences between iPSCs and ESCs.

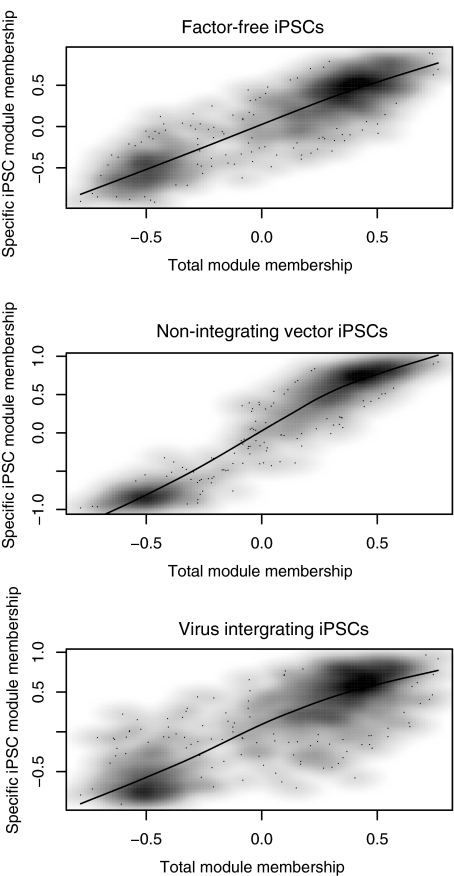

The network modules are conserved across in various iPSCs

To investigate the conservation of network modules across different types of iPSCs, we examined the network module membership of 3 types of iPSCs (ie, virus-integrating-iPSCs, factor-free iPSCs through the cre/loxP system, and vector-free iPSCs with episomal-vectors) by measuring the network module eigengene-based connectivity [26] (Materials and Methods section). We first calculated the total network module membership and then calculated the network module membership of each type of iPSCs separately. We then correlated the total network module membership with each type of iPSCs (Materials and Methods section). The module memberships of these 3 types of iPSCs are highly correlated with total modules (rho 0.78–0.92; Fig. 4). The slight difference in correlation coefficient between cell types from 0.92, 0.85, to 0.78 may result from sample sizes in different subsets of above 3 types of iPSCs and biological experiment variations, but overall they are very similarly correlated to total network. Therefore, our data indicate that the network modules identified above are overall conserved in different types of iPSCs.

FIG. 4.

Network module membership in subtypes of iPSCs. Correlation of total network module membership (x-axis) and module membership of specific subtypes of iPSCs (y-axis). Three subtypes of iPSCs were presented here, factor-free iPSCs (rho=0.85), iPSCs with nonintegrating episomal vectors (rho=0.92), and retrovirus-integrating iPSCs (rho=0.78).

To determine the extent of functional module conservation in different species, we investigated the conservation of these functional modules in mouse iPSCs. Global analysis of mouse iPSC and ESC datasets available in GEO database from different microarray platforms revealed that the primary human functional modules, including transcription, development, metabolism, and immune response, are consistently conserved in all mouse datasets (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. S1A–C). Together, our data demonstrate that distinctively expressed functional modules are highly conserved molecular features distinguishing iPSCs and ESCs.

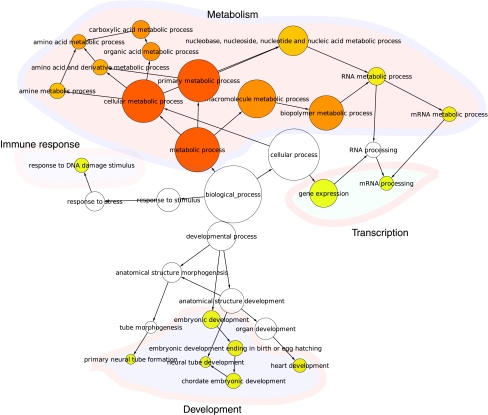

FIG. 5.

Different functional modules are conserved in mouse iPSCs and ESCs. Gene ontology analysis showed functional modules are conserved in mouse iPSCs versus ESCs comparisons, similar to human iPSCs and ESCs. Presented here are the functional module annotations of mouse iPSCs versus ESCs extracted from GEO number GSE16062 as measured by Illumina microarray platform. Larger node size represents the higher density of genes, and dark node color represents greater significance (adjusted P value <0.05). For illustration purposes, we grouped all modules with similar functions into a meta-module and labeled it with their corresponding functions. Similar functional conservations were observed in Affymetrix mouse datasets (Supplementary Fig. S1). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

Analysis of hub genes in the network

The highly connected hub genes may play crucial roles in a network; we searched for such hub genes by ranking the genes based on the network connectivity that considers both the network topology and the eigengene-based connectivity (Materials and Methods section) [26,27]. We selected the top 35 hub genes (Table 2, Supplementary Table S2), which represents ∼5% of total genes in this network, including the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 1 (EIF2AK1, P value <2.0e-19). In silico knockout [33] of these top genes resulted in significant perturbations in network diameter compared with random simulation (Supplementary Fig. S2A), further indicating that these genes contribute significantly to the network structure. These key genes are found in large modules with high connectivity, such as module M1, M3, M6, and M16 (Supplementary Fig. S2B), and exhibit highly coherent expression with their modules (Fig. 6A), indicating that they are central genes within their modules. Surprisingly, the top genes show similar expression across different iPSCs (Fig. 6B–D), indicating that they are consistently important for all iPSCs.

Table 2.

Top 35 Hubs

| ID | Gene symbol | Total score |

|---|---|---|

| 1557215_at | AK056212 | 2.74 |

| 206778_at | CRYBB2 | 2.70 |

| 206777_s_at | CRYBB2 | 2.66 |

| 229155_at | BF508891 | 2.65 |

| 229026_at | BE675995 | 2.65 |

| 217736_s_at | EIF2AK1 | 2.61 |

| 227785_at | SDCCAG8 | 2.61 |

| 228727_at | ANXA11 | 2.54 |

| 226253_at | LRRC45 | 2.49 |

| 216098_s_at | HTR7 | 2.45 |

| 202818_s_at | TCEB3 | 2.42 |

| 213489_at | MAPRE2 | 2.42 |

| 229883_at | GRIN2D | 2.41 |

| 1569191_at | ZNF826 | 2.41 |

| 230499_at | AA805622 | 2.41 |

| 207036_x_at | GRIN2D | 2.41 |

| 225337_at | ABHD2 | 2.38 |

| 225601_at | HMGB3 | 2.38 |

| 1558333_at | C22orf15 | 2.37 |

| 240997_at | AA455864 | 2.37 |

| 220870_at | NM_018503 | 2.36 |

| 228160_at | LOC400642 | 2.34 |

| 204906_at | RPS6KA2 | 2.33 |

| 229378_at | STOX1 | 2.33 |

| 229939_at | AA926664 | 2.33 |

| 240071_at | AI800790 | 2.32 |

| 243027_at | IGSF5 | 2.32 |

| 1564359_a_at | LOC339260 | 2.32 |

| 227732_at | ATXN7L1 | 2.32 |

| 242385_at | RORB | 2.32 |

| 207818_s_at | HTR7 | 2.31 |

| 235333_at | B4GALT6 | 2.31 |

| 237709_at | AI698256 | 2.28 |

| 230439_at | LOC389458 | 2.28 |

FIG. 6.

Coherent expression of top key genes in the network. (A) An example of the coherent expression pattern between the turquoise module and 17 key genes located inside turquoise module. (B–D) Gene expression patterns of top key genes are conserved in different subtypes of iPSCs, for example, those derived from nonintegrating episomal vectors iPSCs (B), virus integrating iPSCs (C), and factor-free iPSCs (D). For clear illustration, only top 10 genes were shown. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

While relatively little is known about most of these hub genes, a few genes with known functions can be classified into the following functional groups: cell development and differentiation (HMGB3, RORB), immune response and translation initiation (EIF2AK1 and ABHD2), transcription (TCEB3), metabolism (GRIN2D), magnesium ion binding and enzyme activity (RPS6KA2,GRIN2D,B4GALT6), and calcium-dependent phospholipid binding(ANXA11). This indicated that functional differences for these 2 cell types are still primarily in transcription, development, metabolism, and immune response, consistent with our finding observed above. Thus, our data uncovered top genes that regulate their corresponding protein module expression and potentially contribute to functional differences between iPSCs and ESCs.

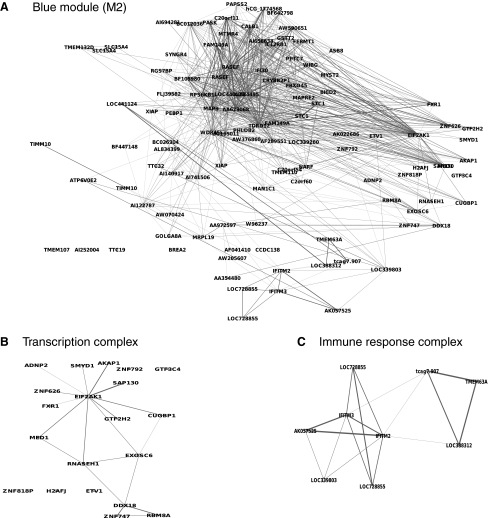

The largest and most significantly altered module primarily functions in transcription

After viewing the global properties of the entire network, we next examined details of particular modules. We first explored the most significantly altered module M2 (blue, P<2.5e-28), which is downregulated in iPSCs with 110 nodes and also the second largest module in terms of gene number (Fig. 7A, Table 1). Based on gene ontology and network topology, this module primarily contained 2 protein complexes functioning in transcription (Fig. 7B, Supplementary Fig. S3), and immune response (Fig. 7C). Genes in the gene expression complex were enriched with transcription factors, especially zinc finger proteins (Fig. 7B), including MYST2, MED1, GTF3C4, ZNF818P, EIF2AK1, DDX18, EXOSC6, RBM8A, CUGBP1, RNASEH1, AKAP1, FXR1, GTF2H2, ZNF792, SMYD1, H2AFJ, ZNF626, ADNP2, ZNF747, SAP130, and ETV1. The whole transcription complex was centered at EIF2AK1 and was strongly connected with other components (Fig. 7B). EIF2AK1 strongly interacts with MED1 (mediator complex subunit 1), a subunit important for efficient transcription initiation. EIF2AK1 is functionally involved in an array of bioprocesses, such as regulation of translation, apoptosis with FXR1, and viral immune response, indicating that translation and programmed cell death also strongly interact with transcription machinery in the complex. The immune response module (Fig. 7C) includes 2 genes (interferon induced transmembrane protein, IFITM3, IFITM2) feathered with broad functions in immune response to stimuli, leading to transcription initiation. This indicates that the whole module (M2, blue) primarily functions in mediating gene expression.

FIG. 7.

Network structure of M2 module (blue). (A) Gene interaction network in the entire module. (B) Genes and their interactions form a complex functionally enriched for transcription (B) and immune response (C).

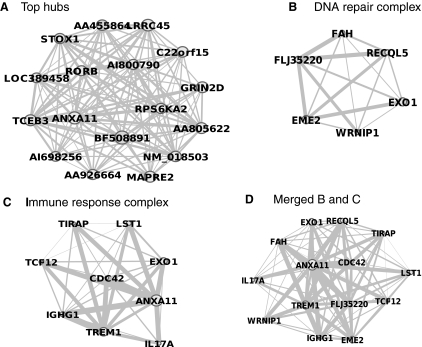

We next decomposed the most predominant module (M16, turquoise; Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S4) with 163 genes and 12,692 interactions, downregulated in iPSCs. Because most genes in the module have unknown functions, we focus on genes with known functions to discuss the primary functions of this module.

The majority of key proteins, 17 of 35 crucial genes identified in the network, are located in this module (Fig. 8A). These genes strongly interact with each other (Fig. 8A) and it is therefore difficult to determine the most important gene. Key genes with known functions are associated with transcription (including RORB and TCEB3), indicating that transcription is the primary process mediated by the key genes in the entire network differentially expressed between iPSCs and ESCs.

FIG. 8.

Decompositions of the most dominated network module (M16, turquoise, Supplementary Fig. S4). (A) Interactions of top 17 genes (out of total 35 top identified genes) in this module. For visualization propose, the weak interactions were deleted. (B) DNA repair complex. (C) Immune response complex. (D) Merged complex from (B, C).

Two other primary functional protein complexes were found in the modules DNA repair (Fig. 8B) and immune response (Fig. 8C). The DNA repair complex consists of 6 genes centered around EXO1 and RECQL5 (Fig. 8B), including EXO1, FLJ35220, RECQL5, WRNIP1, EME2, and FAH, whereas immune response complex contains 9 genes centered around EXO1 and TREM1, including EXO1, IGHG1, CDC42, IL17A, LST1, ANXA11, TIRAP, TREM1, and TCF12. These 2 groups overlapped very well both in interactions and in key genes like EXO1 (Fig. 8D), suggesting that the overall function of these 2 complexes is immune response to DNA damage. Together, our module data suggest that the differences in transcription and immune response between iPSCs and ESCs are primary molecular features distinguishing these 2 cell types.

Discussion

A critical question we must answer before applying iPSCs in regenerative medicine is how close iPSCs resemble ESCs and whether there are any features distinguishing them. Here, we reveal that iPSCs generated to date still inherently express distinctive transcriptome compared with ESCs, and that these 2 cell types can be distinguished by several basic biological modules.

Experimental conditions such as cell culture, cell handling, and treatment conditions have been proposed as factors that contribute to stochastic variations in iPSCs transcriptome [1–2,10]. This seemed true after observing lab-specific iPSC transcriptome profiling [11,12]. However, these lab-specific patterns were drawn from microarray analyses without adjusting for batch effects, which is notorious for misleading microarray data interpretation [15]. In addition, these patterns [11,12] were generated from cluster analysis that has low sensitivity for discriminating samples with high dimensions. In this study, we removed the batch effects from all datasets and employed between-group analysis [32] to re-analyze the iPSC samples. Between-group analysis uses a standard conversion method such as correspondence analysis to calculate an ordination of sample groups rather than that of individual microarray samples and thus it has a discriminating power compatible to artificial neural network with high sensitivity. Our analysis revealed that the lab-specific iPSC profiling is a consequence of batch effects in microarray data (Fig. 1A, C right panel) and that, after removing batch effects, we find iPSCs are clearly separated from ESCs (Fig. 1B, C right panel). This indicates that human iPSCs inherently express distinctive transcriptome compared with ESCs.

Here, we employed systems biology approaches based on WGCNA to systematically investigate the system-wide biological picture between these 2 cell types and revealed conserved molecular features distinguishing these 2 cell types. Our analysis revealed a network containing 17 modules differentially expressed in iPSCs and ESCs (Fig. 2, Table 1). These modules can be grouped into meta-modules based on functions and they primarily function in transcription, metabolism, development, and immune response. Strikingly, the functional modules are highly conserved in various iPSCs (Fig. 4). This conservation relationship was measured by the module membership correlation based on the network eigengene scores, which uses the principle component of high dimension data and thus captures the maximum information that may explain the natural relationship of the variables.

The modules identified in this study can be used as quantitative variables to classify samples and to predict the new samples (Fig. 3). By employing SVMs, our module-based models successfully discriminate these 2 cell types with a very high accuracy, ∼96% for models based on both 17 modules and 4 meta-modules (transcription, metabolism, immune response, and development). Even with 2 meta-modules (transcription and metabolism), our model reaches a 94% accuracy (Fig. 3C–E). Together, coherent co-expression, conservation, and discriminating powers of these modules suggest that these functional modules identified here serve as inherently conserved features distinguishing iPSCs and ESCs. This further suggests that these 2 cell types exhibit the distinctive differences in fundamental biological functions such as in transcription and metabolism. Consistently, recent studies have observed improvements in transcription and metabolism during iPSC production by adjusting transcription factor composition and hypoxia condition [34], adding microRNAs [35], and other factors like vitamin D [36]. Furthermore, enzyme activity differences in metabolism between iPSCs and ESCs may explain the recent observations showing that modified culture medium enhances the iPSCs generation [36]. Therefore, iPSCs have unique distinguishing features to ESCs.

Altered expression of functional modules may be modulated by many mechanisms, including epigenetic and genetic factors. Our data uncovered an overall inverse correlation between module expression and DNA methylation level (Fig. 3). We observed a similar trend even when we expanded our data set with 67 samples (unpublished data), suggesting that DNA methylation may serve as one epigenetic mechanism underlying functional module differences. Our present result on DNA methylation differences parallels the most current observations showing that iPSCs retain DNA methylation patterns from original somatic cells [10,37], and that iPSCs differentially express a panel of DNA methylation sites compared with ESCs [38–40]. Further biological experiments and bioinformatics algorithms are needed to fully understand the role of DNA methylation in regulating these modules. Recently, copy number variations are uncovered in iPSC compared with the parental somatic cells, suggesting that genetic changes can also take place in iPSC derivation [41,42]. Thus, we cannot rule out that genetic changes may also contribute to functional differences of human iPSCs and ESCs.

Our study systematically reveals inherent functional modules that are uniquely activated in iPSCs. Our findings provide an avenue to guide the further efforts on overcoming the barriers of transcriptional differences between iPSCs and ESCs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors deeply appreciate Dr. Peter Langfelder for providing assistance during data analysis. This work is supported by CIRM RC 1-00111 grant, NIH PO1 GM 081621, 2011CB965102, and 2011CB966204 from Ministry of Science and Technology in China.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Yamanaka S. A fresh look at iPS cells. Cell. 2009;137:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamanaka S. Elite and stochastic models for induced pluripotent stem cell generation. Nature. 2009;460:49–52. doi: 10.1038/nature08180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi K. Tanabe K. Ohnuki M. Narita M. Ichisaka T. Tomoda K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu J. Vodyanik MA. Smuga-Otto K. Antosiewicz-Bourget J. Frane JL. Tian S. Nie J. Jonsdottir GA. Ruotti V, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samavarchi-Tehrani P. Golipour A. David L. Sung HK. Beyer TA. Datti A. Woltjen K. Nagy A. Wrana JL. Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soldner F. Hockemeyer D. Beard C. Gao Q. Bell GW. Cook EG. Hargus G. Blak A. Cooper O, et al. Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell. 2009;136:964–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordes KR. Sheehy NT. White MP. Berry EC. Morton SU. Muth AN. Lee TH. Miano JM. Ivey KN. Srivastava D. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460:705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou H. Wu S. Joo JY. Zhu S. Han DW. Lin T. Trauger S. Bien G. Yao S, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polo JM. Liu S. Figueroa ME. Kulalert W. Eminli S. Tan KY. Apostolou E. Stadtfeld M. Li Y, et al. Cell type of origin influences the molecular and functional properties of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:848–855. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guenther MG. Frampton GM. Soldner F. Hockemeyer D. Mitalipova M. Jaenisch R. Young RA. Chromatin structure and gene expression programs of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman AM. Cooper JB. Lab-specific gene expression signatures in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin MH. Mason MJ. Xie W. Volinia S. Singer M. Peterson C. Ambartsumyan G. Aimiuwu O. Richter L, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are distinguished by gene expression signatures. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stadtfeld M. Apostolou E. Akutsu H. Fukuda A. Follett P. Natesan S. Kono T. Shioda T. Hochedlinger K. Aberrant silencing of imprinted genes on chromosome 12qF1 in mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;465:175–181. doi: 10.1038/nature09017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson WE. Li C. Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8:118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szabo E. Rampalli S. Risueno RM. Schnerch A. Mitchell R. Fiebig-Comyn A. Levadoux-Martin M. Bhatia M. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to multilineage blood progenitors. Nature. 2010;468:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nature09591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh Z. Wilson KD. Wu Y. Hu S. Quertermous T. Wu JC. Persistent donor cell gene expression among human induced pluripotent stem cells contributes to differences with human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langfelder P. Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang B. Horvath S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2005;4 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1128. Article 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravasz E. Somera AL. Mongru DA. Oltvai ZN. Barabasi AL. Hierarchical organization of modularity in metabolic networks. Science. 2002;297:1551–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.1073374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li A. Horvath S. Network neighborhood analysis with the multi-node topological overlap measure. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:222–231. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yip AM. Horvath S. Gene network interconnectedness and the generalized topological overlap measure. BMC Bioinform. 2007;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghazalpour A. Doss S. Zhang B. Wang S. Plaisier C. Castellanos R. Brozell A. Schadt EE. Drake TA. Lusis AJ. Horvath S. Integrating genetic and network analysis to characterize genes related to mouse weight. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong J. Horvath S. Understanding network concepts in modules. BMC Syst Biol. 2007;1:24. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oldham MC. Horvath S. Geschwind DH. Conservation and evolution of gene coexpression networks in human and chimpanzee brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17973–17978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvath S. Dong J. Geometric interpretation of gene coexpression network analysis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mason MJ. Fan G. Plath K. Zhou Q. Horvath S. Signed weighted gene co-expression network analysis of transcriptional regulation in murine embryonic stem cells. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:327. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cortes Corinna. Vapnik V. Support-vector network. Machine Learning. 1995;20:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou H. Wu S. Joo JY. Zhu S. Han DW. Lin T. Trauger S. Bien G. Yao S, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J. Hu K. Smuga-Otto K. Tian S. Stewart R. Slukvin II. Thomson JA. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science. 2009;324:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1172482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim D. Kim CH. Moon JI. Chung YG. Chang MY. Han BS. Ko S. Yang E. Cha KY. Lanza R. Kim KS. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Culhane AC. Perriere G. Considine EC. Cotter TG. Higgins DG. Between-group analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1600–1608. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.12.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang A. Johnston SC. Chou J. Dean D. A systemic network for Chlamydia pneumoniae entry into human cells. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2809–2815. doi: 10.1128/JB.01462-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida Y. Takahashi K. Okita K. Ichisaka T. Yamanaka S. Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Judson RL. Babiarz JE. Venere M. Blelloch R. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs promote induced pluripotency. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:459–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esteban MA. Wang T. Qin B. Yang J. Qin D. Cai J. Li W. Weng Z. Chen J, et al. Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim K. Doi A. Wen B. Ng K. Zhao R. Cahan P. Kim J. Aryee MJ. Ji H, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nature09342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doi A. Park IH. Wen B. Murakami P. Aryee MJ. Irizarry R. Herb B. Ladd-Acosta C. Rho J, et al. Differential methylation of tissue- and cancer-specific CpG island shores distinguishes human induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1350–1353. doi: 10.1038/ng.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lister R. Pelizzola M. Kida YS. Hawkins RD. Nery JR. Hon G. Antosiewicz-Bourget J. O'Malley R. Castanon R, et al. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bock C. Kiskinis E. Verstappen G. Gu H. Boulting G. Smith ZD. Ziller M. Croft GF. Amoroso MW, et al. Reference Maps of human ES and iPS cell variation enable high-throughput characterization of pluripotent cell lines. Cell. 2011;144:439–452. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hussein SM. Batada NN. Vuoristo S. Ching RW. Autio R. Narva E. Ng S. Sourour M. Hamalainen R, et al. Copy number variation and selection during reprogramming to pluripotency. Nature. 2011;471:58–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laurent LC. Ulitsky I. Slavin I. Tran H. Schork A. Morey R. Lynch C. Harness JV. Lee S, et al. Dynamic changes in the copy number of pluripotency and cell proliferation genes in human ESCs and iPSCs during reprogramming and time in culture. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.