Abstract

The metabolism of doxorubicin, a widely used anticancer drug, is different in young adult and old cancer patients. In this study, we demonstrate that micellar electrokinetic chromatography with laser-induced fluorescence detection is highly suited to monitor the metabolism of doxorubicin in subcellular fractions isolated from young adult (11 months, 100% survival rate) and old (26 months, ∼25% survival rate) Fischer 344 rat livers. The relative amounts of doxorubicin metabolized in both mitochondria-enriched and postmitochondria fractions of young adult were larger than the respective fractions of old rat liver. 7-Deoxydoxorubicinolone and 7-deoxydoxorubicinone were identified using internal standard addition and structural elucidation by high-performance liquid chromatography with combined laser-induced fluorescence and mass spectrometry detection. Although high-performance liquid chromatography with combined laser-induced fluorescence and mass spectrometry detection is more useful in the identification of compounds, micellar electrokinetic chromatography with laser-induced fluorescence detection has low-sample requirements, simplified sample processing procedures, short analysis times and low limit of detection. Therefore, the combination of these two techniques provides a powerful approach to investigate metabolism of fluorescent drugs in aging studies.

Keywords: Metabolism, Doxorubicin, Capillary electrophoresis, Fluorescence, HPLC-MS

THE majority of patients with cancer are 65 years and older. Although the administered chemotherapy treatments to this age group have been evaluated in clinical trials, the elder is usually underrepresented in such trials (1,2). Thus, the findings of such trials cannot be directly extrapolated to the use of chemotherapy drugs in the elder. The pharmacokinetics and toxicity of doxorubicin (DOX) and other chemotherapy drugs such as etoposide, ifosfamide, daunorubicin, mitomycin, cisplatin, and methotrexate are influenced by aging (3). Because the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of a given compound depend on the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of such a compound, evaluation of how each one of these parameters changes with aging is of paramount importance (4).

The liver is key in the metabolism and hepatic clearance of xenobiotics (5). Unfortunately, assessing liver function in vivo using either human or animal subjects is plagued with multiple confounding factors and methodological artifacts. Such studies are particularly complicated in the elder who take multiple medications. In addition, such studies are more powerful when the same subject is monitored over time (ie, longitudinal studies). With the exception of plasma or blood sampling, the limited sample volumes at each sampling time make them incompatible with the sensitivity of current analytical methodologies. Comparison of young and old liver metabolism using sensitive methodologies may provide new resources to understand age-related changes in chemotherapeutic metabolism.

DOX is a widely used anticancer drug in treating solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, such as breast cancer and leukemia, respectively (6). Studies of DOX in rat showed that the area under the concentration-time curve (plasma and cardiac) of doxorubicinol (DOXol), which is associated with cardiotoxicity (7), increased in old compared with young rats (8,9). In agreement, equal chemotherapy treatments, including treatment with DOX, accelerated toxicity in old relative to younger patients (10). These studies were interpreted as if the observed changes in metabolism were associated with the cytotoxic effects observed in the elderly population. Thus, understanding the altered metabolism of chemotherapy drugs in elderly persons may help to administrate proper dose and avoid adverse effects.

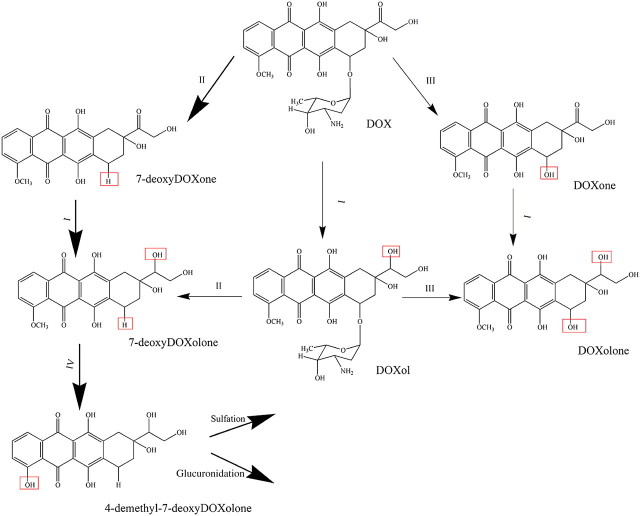

A schematic representation of DOX metabolism is shown in Figure 1. This drug is metabolized by microsomal, an aldo-ketoreductase dependent on the reduced form of β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate (NADPH) hydrolase-type deglycosidase, reductase-type deglycosidase, uridine diphosphate glucuronyltransferase, and sulfotransferase activities (11–13). The metabolism and elimination of DOX are primarily done through the hepatobiliary route (14). Although there is some consensus on the reduction in hepatic drug metabolism with age (15), the effect of aging on hepatic enzymes is still controversial because of other factors such as the lipophilic nature of the drug (4). Different hepatic enzymes respond differently to aging, and they may display change in abundance or activity (16,17). Particularly, studies have focused on cytochrome P450 enzymes (18,19). So far, there are no reports on the age-related changes in enzymatic activities associated with DOX metabolism.

Figure 1.

Possible doxorubicin (DOX) metabolic pathways (13). Changes in the chemical structures upon reaction are indicated by boxes. (I) Carbonyl reduction by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-dependent carbonyl reductase, (II) reductase-type deglycosidation by NADPH-cytochrome c reductase, (III) hydrolase-type deglycosidation by glycosidase, and (IV) demethylation by cytochrome P450. The possible metabolic pathway of DOX in this study is shown in bold arrows.

Micellar electrokinetic chromatography with laser-induced fluorescence detection (MEKC-LIF) is ideal for the analysis of fluorescent compounds, such as DOX and its metabolites. It has low limits of detection (ie, 10−18 to 10−20 mole of DOX), making it possible to detect low-abundant metabolites, which cannot be otherwise detected (20,21). In addition, samples are directly dissolved in the separation buffer containing a surfactant, making sample extraction unnecessary and avoiding analyte losses during the extraction. Moreover, micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC) only requires nanoliter sample volumes, which is advantageous in the analysis of small volumes, such as those from subcellular fractions. On the other hand, MEKC-LIF alone cannot provide unique identification of metabolites. Other techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry detection are more suitable to identify metabolites (22), albeit lacking the attributes of MEKC-LIF mentioned above.

In this study, we first used high-performance liquid chromatography with combined laser-induced fluorescence and mass spectrometry detection (HPLC-LIF-MS) to identity the detectable most abundant metabolites, 7-deoxydoxorubicinone (7-deoxyDOXone) and 7-deoxydoxorubicinolone (7-deoxyDOXolone). Second, we used MEKC-LIF to obtain a more sensitive description of DOX metabolism in subcellular fractions (mitochondria-enriched fraction [MF] and postmitochondria fraction [PMF]) from livers of young adult (11 months, 100% survival rate) and old (26 months, ∼25% survival rate) Fischer 344 rats. Aided by spiking of samples with neat standards and the complementary analysis of PMF by HPLC-LIF-MS, we noted by MEKC-LIF that DOXol and doxorubicinone (DOXone) are not detectable in in vitro rat liver metabolism and suggested that two of the detected metabolites are 7-deoxyDOXone and 7-deoxyDOXolone. Furthermore, MEKC-LIF detected two unidentified metabolites in young adult liver that were absent in the old liver; one of these metabolites was also absent in the young adult MF. Although the PMF is more metabolically active than the MF in both young adult and old rats, DOX metabolism was clearly reduced in the old relative to the young adult livers. The analytical approach to monitor subcellular metabolism holds promise in studying the effect of aging on drug metabolism in longitudinal animal models and human tissue biopsies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Reagents

DOX hydrochloride was a generous gift from Meiji Seika Kaisha Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). DOXol and doxorubicinone were from Qvantas Inc. (Newark, DE). Bradford reagent, protease inhibitor cocktail, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase type I, D-glucose-6-phosphate dipotassium salt hydrate, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+) and NADPH tetrasodium salt were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). NADP+ was purchased from Roche Diagnostics, GmBH (Mannheim, Germany). Sodium dodecyl sulfate, hydrochloric acid (HCl), perchloric acid, magnesium chloride, potassium phosphate monobasic, and dibasic were from Mallinckrodt (Phillipsburg, NJ). Sodium borate decahydrate and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were from Fischer Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Phosphate-buffered saline (10×; containing 1.37 M NaCl, 14.7 mM KH2PO4, 78.1 mM Na2HPO4, and 26.8 mM KCl) was from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). γ-Cyclodextrin (γ-CD) was from TCI America (Portland, OR). Fluorescein was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH = 7.4) with 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail was used as homogenization and incubation buffer. MEKC separation buffer was made up of 50 mM borate, 50 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 20 mM γ-CD, pH = 9.3 (BS50-γ-CD20).

Preparation of Liver Subcellular Fractions

Liver samples were obtained from a pair of young adult (11 months old) and old (26 months old) female Fischer 344 rats with a life span of 29 months (23). The animal protocol was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The livers were removed after anesthesia and kept on ice-cold 1× phosphate-buffer saline until homogenization (within 30 min of removal). They were cut into small pieces and washed with 1× phosphate-buffer saline three times. After washing, they were homogenized (1.5 mL homogenization buffer was added to 1 g liver sample) by five strokes in an ice-chilled Dounce homogenizer (0.00025” clearance; Kontes Glass, Vineland, NJ). The homogenate was centrifuged at 600g for 10 min to remove nuclei, intact cells, and liver debris. The supernatant (postnuclear fraction) was further centrifuged at 9,000g. The resulting supernatant (PMF) was saved for further use and the pellet (MF) was reconstituted in incubation buffer. The MF also contains lysosomes and peroxisomes; the PMF is made up of microsomes and cytosol. The protein amounts in the MF and PMF were determined using a Bradford assay according to the manufacture’s (Sigma-Aldrich) protocol. The volume of the two fractions was adjusted with incubation buffer, so that the protein concentrations were the same in both fractions (∼8 mg/mL).

Identification of Abundant DOX Metabolites by HPLC-LIF-MS

HPLC-LIF-MS was used to identify abundant metabolites produced during in vitro metabolism of DOX in rat livers. This method has been described previously (24). Briefly, DOX (50 μM) was incubated with PMF of young adult and old rat livers with the addition of NADPH-generating system, ie, MgCl2 (5 mM), Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (0.25 mM), glucose-6-phosphate (2.5 mM), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (2.0 U; final volume of 1.1 mL) at 37°C in a heated mixer (Eppendorf Thermomixer). A small volume of the reaction mixture (40 μL) was removed at 10, 20, 30 and 40 min for extraction of DOX and its metabolites. Each volume was treated with 14 μL of concentrated perchloric acid and mixed with 60 μL of HPLC mobile phase (67% water: 33% acetonitrile). The resulting mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 3000g for 3 min. The supernatant was used directly for HPLC-LIF-MS analysis. Note: The acid treatment of DOX causes formation of DOXone; thus, its detection by HPLC-LIF-MS does not imply that DOXone is a natural metabolite.

An Agilent (Santa Clara, CA) 1100 capillary HPLC system was used for HPLC-LIF-MS analysis. A sample volume of 0.5 μL was injected into the HPLC apparatus and separated on a C18 column (0.3 × 150 mm, 3 μm particles, ACE11115003; Mac-Mod Analytical, Inc., Chadds Ford, PA). The mobile phase consisted of 67% water (0.1% formic acid) and 33% acetonitrile. The flow rate was set at 3.5 μL/min. For LIF detection, a 473-nm diode-pumped solid-state laser (OnPoint Lasers; LTD, Eden Prairie, MN) was used for excitation. An approximately 5-mm section of the polyimide coating of the fused silica capillary was burned off, creating a detection window. A fluorescence flow-through cell (SpectrAlliance, Inc., St Louis, MO) equipped with fiber optics to deliver incident light and collect fluorescent light was used as an on-column detector. The collected fluorescence was filtered with a 580BP45 filter (Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT) and monitored using a photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) biased at 800 V. Data from the photomultiplier tube was digitized (10 Hz) using a National Instruments I/O board (PCI-6034E) run with a LabVIEW 5.1.1 (National Instruments, Austin, TX) program created in house. Mass spectral data were collected using a Bruker MicrOTOFQ mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA) using positive ion mode. The parameters (funnel 1 and 2 radio frequency, hexapole radio frequency and collision radio frequency) were adjusted to achieve a maximum detection of DOX and metabolites.

MEKC-LIF Analysis of the In Vitro DOX Metabolism

DOX (10 μM) and cofactors (1 mM NADPH and 5 mM MgCl2) were added into MF and PMF for in vitro metabolism. The start of the reaction was defined as the addition of DOX. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C in a heated mixer. Samples were taken out at four different time points (15 min, 30 min, 1 h, and 2 h), and the reaction was stopped by freezing the sample in dry ice. The samples were kept at −80°C until analysis.

The samples were analyzed by MEKC-LIF. Before analysis, MF and PMF were diluted 25 or 50 times with separation buffer. Samples were introduced into a fused silica capillary (50 μm inner diameter and 150 μm outer diameter; Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ) by hydrodynamic injection at 12 kPa for 2 s. Then the capillary was brought into a vial with separation buffer, and MEKC was performed under a +400 V/cm electric field in a home-built instrument equipped with postcolumn LIF detection, previously described (25). Briefly, a sheath flow cuvette encased the detection end of the capillary. The last 2 mm of this end had the polyimide coating burned off to reduce the background fluorescence caused by this material. As fluorescent analytes migrated out from the capillary, they were excited at 488 nm with an argon-ion laser (JDS Uniphase, San Jose, CA). Fluorescence was collected at a 90° angle with respect to the laser beam by a 60× microscope objective (Universe Kogaku, Inc., Oyster Bay, NY). A 505-nm long-pass filter (505 AELP; Omega Optical, and a 1.4-mm pinhole were used to reduce light scattering. A 635 ± 27.5 nm (XF3015; Omega Optical) was used to select fluorescence from DOX and metabolites. Fluorescence was then detected in a photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu) biased at 1000 V. The photomultiplier tube output was sampled at 10 Hz with a data acquisition board driven by Labview software (National Instruments).

Prior to MEKC analysis, the capillary was conditioned with sequential flushes of 0.1 mM NaOH, water, and separation buffer for 30 min each using 150 kPa pressure at the inlet. The separation buffer was replaced every 2 h with a fresh one to avoid electrolyte depletion and buffer contamination. Prior to sample analysis, the instrument was aligned by maximizing the response of 5 ×10−10 M fluorescein which continuously flowed through the detector while applying a +400 V/cm electric field. The limit of detection (S/N = 3) of DOX in BS50-γ-CD20 buffer was (4.9 ± 0.5) × 10−18 mole (n = 3) as determined from the peak intensity resulting from injecting 8.4 × 10−16 mole of DOX.

MEKC-LIF Data Analysis

Electropherograms were processed by Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) to determine peak intensity and area of DOX and metabolites. The peak area of each metabolite (Ai) was adjusted by its fluorescence quantum yield relative to that of DOX:

| (1) |

where Ai,adj is the adjusted peak area of each metabolite and Фi is its fluorescence quantum yield relative to DOX. The fluorescence quantum yields of DOXol and 7-deoxyDOXone relative to DOX were determined by comparing the fluorescence intensities over the 607–663 nm range of equimolar (5 μM) solutions in the MEKC separation buffer (ie, BS50-γ-CD20). This wavelength range was chosen according to the transmission range of the 635 ± 27.5 nm bandpass filter used in MEKC-LIF detector. The fluorescence intensities were measured at 488 nm excitation with a Jasco FP-6200 spectrofluorometer (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan). The relative quantum yields of DOXol and 7-deoxyDOXone relative to DOX were 1.38 and 0.76, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). In the absence of 7-deoxyDOXolone standard, we assumed that its relative quantum yield can be predicted from its molecular similarities with DOXol and 7-deoxyDOXone. Thus, we assumed that the relative quantum yield of 7-deoxyDOXolone to DOX is 1.05. The quantum yields of unidentified metabolites to DOX were assumed to be 1.0.

Because Ai,adj values are proportional to the number of moles detected for compound (i), the molar percent of DOX and metabolites in each reaction mixture was calculated as

| (2) |

Comparisons of molar percent of DOX and metabolites between samples used Student’s t tests. The null hypothesis “there is no significant difference in the relative abundance of a given metabolite X between two different fractions” was rejected when the p value <0.02 (98% confidence level).

RESULTS

Identification of Metabolites

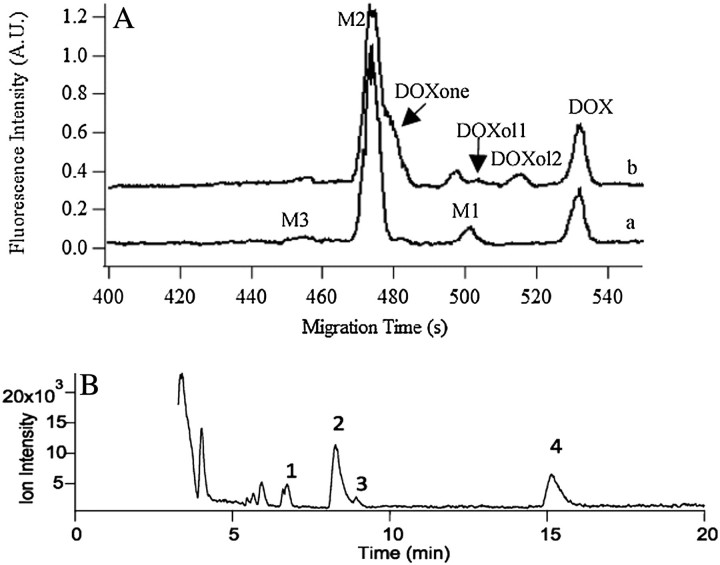

Previous studies have shown that DOX is metabolized to different metabolites (eg, DOXol, DOXone, 7-deoxyDOXone, and 7-deoxyDOXolone) in human and animal subjects through enzymatic reactions that include carbonyl reduction, reductive glycosidic cleavage, hydrolytic glycosidic cleavage, demethylation, sulfation, and glucuronidation (11,26,27). According to Figure 1, in addition to DOX, up to eight additional compounds could be detected as a result of DOX metabolism. However, fewer compounds are typically expected in metabolite analysis. For instance, MEKC-LIF revealed three peaks after incubating DOX with the MF of a young adult rat liver for 1 h (Figure 2A, Trace a). Similarly, HPLC-LIF-MS revealed four compounds (1 = DOX, 2 = 7-deoxyDOXolone, 3 = DOXone, and 4 = 7-deoxyDOXone, Figure 2B), but DOXone is not related to DOX metabolism. DOXone forms as a result of acid-catalyzed cleavage of the daunosamine sugar during the sample preparation (24). Other peaks detected in the HPLC-LIF-MS chromatograms corresponded to sample matrix (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Identification metabolites with the aid of internal standard addition and HPLC-LIF-MS. (A) Electropherograms of 10 μM doxorubicin (DOX) incubated in mitochondria-enriched fraction (MF) for 1 h (Trace a) and with internal addition of DOX, DOXol, and DOXone (Trace b). Trace b is y-axis offset for clarity. M1 is 7-deoxyDOXone and M2 is 7-doxyDOXolone. Separations were performed in a 45.7-cm long, 50-μm i.d.–fused silica capillary at 400 V/cm in BS50-γ-CD20 buffer. Analytes were excited at 488 nm and fluorescence was detected at 635 ± 27.5 nm. (B) Mass chromatogram of DOX metabolites formed in a liver postmitochondria fraction (PMF). The PMF was treated with 50 μM doxorubicin and acid extracted after 10 min. Separation was conducted in a 150 × 0.3 mm C18 column under isocratic conditions (67% water, 0.1% formic acid: 33% acetonitrile). The ESI-MS used a Mass spectrometry was done with a Bruker MicrOTOFQ instrument. Peak 1: DOX, 2: 7-deoxyDOXolone, 3: Doxone, and 4: 7-deoxyDOXone. Doxone is formed during sample preparation and is not considered a natural metabolite (24).

Because the goal of these studies was to exploit the high sensitivity and low-sample requirements of MEKC-LIF to monitor the age-related changes of the in vitro metabolism of DOX in rat liver fractions, we aimed to identify the peaks in the MEKC-LIF electropherograms using (a) internal standard addition and (b) relative electrophoretic mobilities of the various compounds. The latter could be associated with the retention times observed in HPLC-LIF-MS.

We used the addition of DOXol and DOXone standards to narrow down on the identity of the metabolite peaks (Figure 2A, Trace a). The addition of DOXol resulted in the appearance of two more peaks (DOXol1 and DOXol2, Figure 2A, Trace b), previously reported to correspond to DOXol enantiomers (25). Neither of the peaks overlapped with the peaks observed in the original sample (Figure 2A, Trace a). Thus, DOXol was not detected. Addition of DOXone standard resulted in the appearance of a shoulder peak on M2 (Figure 2A, Trace b). The similarity in migration times of M2 and DOXone suggests that M2 has a molecular structure similar to DOXone, but it is not DOXone.

To further identify the DOX metabolites detected by MEKC-LIF, we also analyzed the DOX metabolism in rat PMF using HPLC-LIF-MS and identified 7-deoxyDOXone and 7-deoxyDOXolone as the only two detectable metabolites. The more abundant of these two was 7-deoxyDOXolone, and in agreement with MEKC-LIF, no DOXol was detected (Figure 2B) (24). The elution order in the reverse phase mode of the HPLC separation was DOX, 7-deoxyDOXolone, DOXone, and 7- deoxyDOXone, which is in perfect agreement with their relative hydrophobicity and molecular structure (Figure 1). Because these aglycones (ie, those compounds that lack the daunosamine sugar) are expected to be practically electrically neutral, their order of migration is mainly based only their partitioning between the micellar and aqueous phases of the MEKC buffer. That is, the less hydrophobic molecules are expected to migrate faster. Thus, the MEKC migration order and the HPLC elution order are expected to be the same for aglycones. Therefore, M1 is tentatively identified as 7-deoxyDOXone, whereas M2 or M3 could be 7-deoxyDOXolone. Lastly, because 7-deoxyDOXone was more abundant than 7-deoxyDOXolone in the HPLC-LIF-MS studies, the more abundant M2 corresponds to 7-deoxyDOXolone. The least hydrophobic M3 remained unidentified. These assignments will be used in the rest of this report.

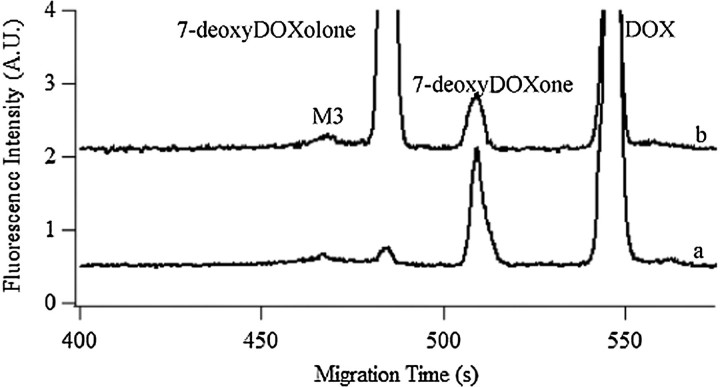

Effect of Cofactors NADPH and Mg2+ on Metabolic Activity

Some of the enzymes involved in DOX metabolism may require NADPH and Mg2+ as cofactors (11,12). In order to further characterize the in vitro DOX metabolism, assays were done in the presence or absence of NADPH and Mg2+ (Figure 3). After 1-h incubation, ∼65% and ∼25% DOX was metabolized, in the presence and absence of cofactors, respectively (Table 1). The enhanced metabolism in the presence of cofactors favored accumulation of 7-deoxyDOXolone and decreased accumulation of 7-deoxyDOXone, which is in agreement with the role NADPH-dependent reductases that may lead to reduction of the carbonyl at the C13 position (c.f., Pathway II, Figure 1). On the other hand, the least hydrophobic M3 did not significantly change with the addition of cofactors (Table 1), which further suggests that this metabolite is further downstream in the DOX metabolism pathways (eg, Phase II metabolism).

Figure 3.

Effect of cofactors on the metabolic activity of rat liver. Electropherograms of 10 μM doxorubicin incubated in MF for 1 h without cofactors (Trace a) or with 1 mM β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate reduced tetrasodium salt hydrate and 5 mM Mg2+ (Trace b); trace b is y-axis offset for clarity. Separations were performed in a 45.3-cm long, 50-μm i.d.–fused silica capillary. Other conditions were same as in Figure 2A.

Table 1.

Fraction of DOX Remaining and Metabolites Formed in the Presence and Absence of Cofactors*

| 7-deoxyDOXone | 7-deoxyDOXolone | M3 | DOX | |

| With cofactors† | 8.0 ± 0.2 | 55.0 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 35.4 ± 0.7 |

| Without cofactors | 20 ± 0 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 75.6 ± 0.5 |

Notes: DOX = Doxorubicin.

Values are in mole percent. According to equation 2, 100% mole corresponds to the sum of all metabolites and DOX detected in a given sample. Errors are equal to 1 SD (n = 3).

Cofactors: 1 mM NADPH and 5 mM Mg2+.

Metabolism in the MF and PMF of Young Adult and Old Rat Liver

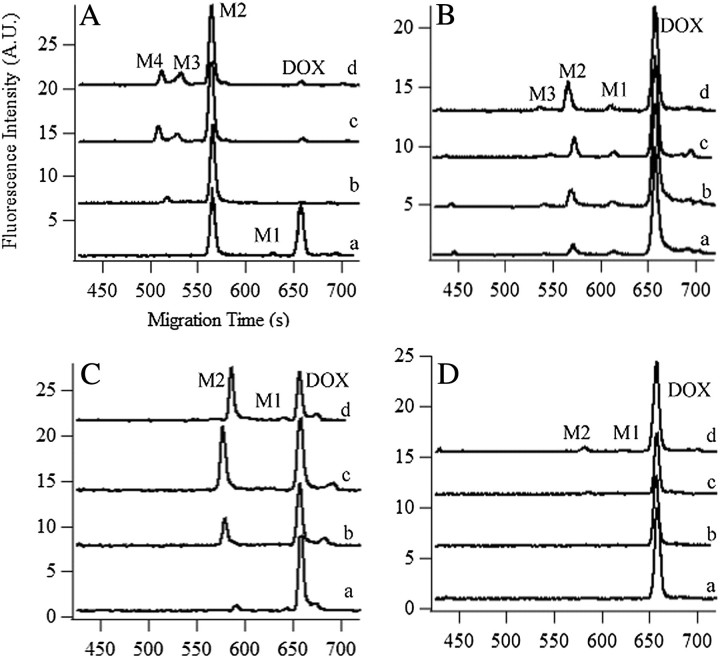

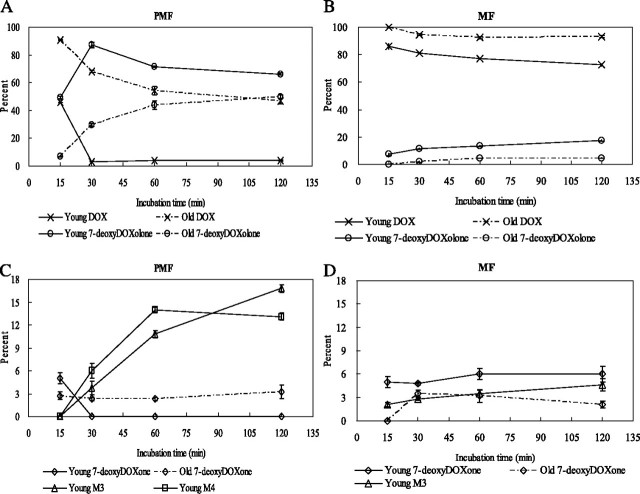

We determined that the MF and PMF of the young adult are more metabolically active than the respective fractions in the old rat (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S1). In the PMF of the young adult rat liver, more than 95% DOX was metabolized, whereas only 53% DOX was metabolized in the old rat liver after a 2-h incubation (Figure 4A and C, respectively). Similarly, in the MF of these rat livers, about 27% and 7% DOX was metabolized in the young adult and old, respectively (Figure 4B and D, respectively).

Figure 4.

In vitro metabolism of doxorubicin (DOX) in postmitochondria fraction (PMF) and mitochondria-enriched fraction (MF) of young adult and old rat livers. Electropherograms of DOX metabolism in (A) PMF of young adult rat liver; (B) MF of young adult rat liver; (C) PMF of old rat liver, and (D) MF of old rat liver after 15 min (trace a), 30 min (trace b), 60 min (trace c), and 120 min (trace d). Traces b, c, and d are y-axis offset for clarity. M1 is 7-deoxyDOXone and M2 is 7-deoxyDOXolone. Separations were performed in a 45-cm (A and B) or 45.8-cm (C and D) long, 50-μm i.d.–fused silica capillary. Other conditions were same as in Figure 2A.

The number of detected metabolites also decreased with age. Four and two metabolites were observed in the PMF of young adult (Figure 4A) and the old (Figure 4C) rat livers. The young adult PMF metabolism involved 7-deoxyDOXone (M1), 7-deoxyDOXolone (M2), M3, and an even less hydrophobic compound M4. The last two were absent in the old PMF metabolism. Three and two metabolites were observed in the MF of young adult (Figure 4B) and the old (Figure 4D) rat livers. The young adult MF metabolism involved 7-deoxyDOXone (M1), 7-deoxyDOXolone (M2), and M3. The last one was absent in the old MF metabolism.

DOX Metabolism in Young Adult and Old as a Function of Time

Using MEKC-LIF, we monitored the changes of DOX and the metabolites observed in the PMF and MF as a function of time. Figure 5A and B shows the results for DOX and 7-deoxyDOXolone in the PMF and MF, respectively. Figure 5C and D shows the results for 7-deoxyDOXone, M3, and M4 in PMF and MF, respectively. The numeric values are tabulated in the Supplementary Table S2. The rate of metabolism was fast during the first 30 min of incubation and then slowed down. The metabolism in PMF of young adult rat liver is different from the rest (Figure 5A). For the PMF, 7-deoxyDOXone was only observed in the first 15-min incubation, and the percent of 7-deoxyDOXolone increased in the first 30 min and then decreased. This temporal pattern is consistent with the transformation of 7-deoxyDOXone into 7-deoxyDOXolone prior to it further metabolic degradation (c.f. Figure 1, Pathways II and IV). These temporal patterns in 7-deoxyDOXolone and 7-deoxyDOXone abundance are consistent with those previously observed by HPLC-LIF-MS (24). In the rest of the samples (ie, young adult MF, old PMF, and old MF), the percent of 7-deoxyDOXone (Figure 5C and D) and 7-deoxyDOXolone (Figure 5A and B) became steady or increased slightly after 30-min incubation. After 30 min of incubation, M3 and M4 were observed in the young adult rat liver PMF (Figure 5C), whereas only M3 was observed in the young adult rat liver MF (Figure 5D). The delayed appearance of M3 and M4 in the most metabolically active system (ie, young adult PMF) further suggests that these compounds are associated with downstream metabolism of DOX. The absence of these compounds in the old PMF and MF suggests that such metabolic pathways are compromised in the old rat liver.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance of doxorubicin (DOX) and its metabolites in postmitochondria fraction (PMF) and mitochondria-enriched fraction (MF) as a function of incubation time. (A) Changes in DOX and 7-deoxyDOXolone in the young adult and old PMF. (B) Changes in DOX and 7-deoxyDOXolone in the young adult and old MF. (C) Changes in 7-deoxyDOXone, M3, and M4 in the young adult and old PMF. (D) Changes in 7-deoxyDOXone and M3 in the young adult and old MF. Percentages (molar) are calculated using equation 2. The young adult and old rat livers are represented in solid and dash lines, respectively. DOX and metabolites are labeled as DOX (×), 7-deoxyDOXone (◊), 7-deoxyDOXolone (o), M3 (Δ), and M4 (□).

DISCUSSION

Elucidation of DOX Metabolism by MEKC-LIF and HPLC-LIF-MS

Understanding age-related changes in metabolism could benefit tremendously from ultrasensitive techniques, such as MEKC-LIF, capable of analyzing extremely small volumes (eg, nanoliter samples). Such techniques would decrease sample demands (eg, enabling ultra-micro-biopsies), making longitudinal studies on animal and human subjects more appealing and less invasive. MEKC-LIF also has high separation efficiency and short separation times and requires little sample preparation, making this technique adequate for fast sampling, which is needed to enhance time profiling while providing the resolution needed to deal with high sample complexity. Because MEKC-LIF has not used previously in any age-related studies, in this report, we took a first step to utilize this technique in an in vitro metabolism involving young adult and old Fischer 344 rat livers.

Because MEKC-LIF does not provide structural information alone, we also utilized HPLC-LIF-MS to identify 7-deoxyDOXolone and 7-deoxyDOXone as the main metabolites formed and detected in the MEKC-LIF analysis. Furthermore, the MEKC-LIF analysis demonstrated that the metabolism of the PMF of young adult rat liver further includes the formation of two more metabolites that were not detected by HPLC-LIF-MS and that remain unidentified (M3 and M4). On the other hand, their shorter migration times relative to that of 7-deoxyDOXolone suggests that M3 and M4 are less hydrophobic than this compound (eg, they may be the sulfation or glucuronidation product of 4-demethyl-7-deoxyDOXolone). Identification of these compounds was outside the scope of this study. Interestingly, these metabolites were absent in the old PMF rat liver metabolism.

DOXol, which is reported as one of the major metabolites of DOX, was not detected in any of our studies agreeing with the previous studies using homogenized rat hepatocytes and livers (27,28). However, Vrignaud and coworkers (28) indicated that DOX aglycone metabolites were only observed in large amounts in homogenized hepatocytes but not in intact ones. They suggested that the homogenization procedure may cause cytolysis and the release of the enzyme that catalyzes the formation of aglycones. Future comparisons between subcellular fractions, whole hepatocytes, and in vivo studies will help further understand differences between these three systems.

Because mitochondria may have a distinct metabolic profile, we also used MEKC-LIF to monitor DOX metabolism in rat liver MF. Relative to the PMF, the MF displayed the same metabolic profile but lower overall metabolic activity suggesting that such differential centrifugation is not sufficient to isolate metabolically distinct subcellular fractions. Lastly, the general decreased in DOX metabolism with aging observed in the MEKC-LIF results demonstrated that this technology could be highly amenable to monitor age-related changes of anthracycline metabolism (ie, fluorescent compounds) and that the DOX metabolism in the rat liver PMF and MF decreases with aging.

Effect of Cofactors on the Metabolism of DOX

NADPH is a cofactor required for oxidoreductase reactions (29). Magnesium is another important cofactor that increases the activity of a number of drug-metabolizing enzymes, such as microsomal NADPH oxidase, NADPH-cytochrome c reductase, and cytochrome P450 reductase (30). In these studies, the addition of NADPH and Mg2+ to the young adult liver fractions decreased 7-deoxyDOXone and increased 7-deoxyDOXolone formation. These changes are consistent with enhanced activity of carbonyl reductase in the presence of such cofactors, which facilitate the transformation of 7-deoxyDOXone to 7-deoxyDOXolone (Figure 1, Pathway II). On the other hand, the relative abundance of M3 did not significantly change with the addition of cofactors further supporting the argument that this less hydrophobic compound is more likely part of Phase II biotransformations. It is worth noticing that NADPH and Mg2+ were always used in the comparison of metabolic time profiles in young adult and old rat liver fractions, described below. Inclusion of these cofactors in the reaction mixture ruled out that the observed age-related changes of DOX, 7-deoxyDOXone, and 7-deoxyDOXolone (described below) were caused by depletion of either NADPH or Mg2+.

DOX Metabolism in Young Adult and Old Rat Livers

The most striking age-related difference in DOX metabolism was the decrease in metabolic activity of the PMF in the old rat liver (Figure 5A and C and Supplementary Table S2). DOX was rapidly consumed in the young adult PMF, whereas half of the original DOX amount has been consumed after 2 h in the old PMF. The 7-deoxyDOXone levels were steady in the old PMF, whereas it was depleted after 30 min in the young adult PMF (Figure 5C). This suggests higher activity of carbonyl reductase, which catalyzes the conversion of 7-deoxyDOXone to 7-deoxyDOXolone, in young adult relative to the old rat liver. Consistently, 7-deoxyDOXolone reaches higher levels in the PMF of young adult relative to the old rat liver (Figure 5A). Similarly, after 30 min, M3 and M4 became detectable and increased in the young adult PMF, whereas they were always absent in the old PMF. As stated above, M3 and M4 are less hydrophobic and could be the glucuronidation or sulfation products of 4-demethyl-7-deoxyDOXolone. The absence of M3 and M4 in the old rat liver may indicate lower activity of the enzymes, such as uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferases (31) and sulfotransferases (32) that catalyze the formation of the conjugates of 4-demethyl-7-deoxyDOXolone. Our findings would then be in agreement with other reports in which these two enzymes showed low activity in old rat livers (33,34).

Because metabolic transformations are only one component of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of chemotherapeutic agents, the studies reported here must be considered proof-of-principle of the potential of MEKC-LIF that may contribute to further elucidate the intricacies of drug treatments in the elder and animal studies. As immediate future work, it would be important to further validate and include MEKC-LIF analysis of metabolism in longitudinal studies that assess hepatic drug clearance and cytotoxicity (3,4,9). Long-term new technologies such as MEKC-LIF may help administer better anthracycline (eg, DOX) treatments to the elder cancer patient (35).

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we demonstrate the synergy of combining HPLC-LIF-MS and MEKC-LIF for identification and monitoring changes in metabolite abundance in young adult and old rat liver samples. HPLC-LIF-MS made possible the identification of 7-deoxyDOXolone and 7-deoxyDOXone as the main metabolic products in the rat liver PMF. Due to its better sensitivity and reproducibility, MEKC-LIF was more suitable to monitor these compounds as a function of time, thereby revealing that young adult rat liver is more metabolically active in both the MF and PMF. MEKC-LIF also uncovered two unidentified metabolites in the young adult that are absent in the old rat liver PMF. Further use of MEKC-LIF in aging studies may contribute to our understanding on the intricacies of drug treatment and aging.

FUNDING

Y.W. was supported by a Merck Graduate Fellowship in Analytical/Physical Chemistry. J.B.K was supported by NIH Training grant T32-AG029796.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material can be found at: http://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor L. Thompson and her research group, primarily W. Torgerud, who handled animal protocols and procedures.

References

- 1.Lichtman SM, Wildiers H, Chatelut E, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology Chemotherapy Taskforce: evaluation of chemotherapy in older patients—an analysis of the medical literature. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(14)):1832–1843. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John V, Mashru S, Lichtman S. Pharmacological factors influencing anticancer drug selection in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2003;20(10):737–759. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200320100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekine I, Fukuda H, Kunitoh H, Saijo N. Cancer chemotherapy in the elderly. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28(8):463–473. doi: 10.1093/jjco/28.8.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klotz U. Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism in the elderly. Drug Metab Rev. 2009;41(2):67–76. doi: 10.1080/03602530902722679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maton AJH, McLaughlin CW, Johnson S, Warner MQ, LaHart D, Wright JD. Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum RH, Carter SK. Adriamycin. A new anticancer drug with significant clinical activity. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80(2):249–259. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-2-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cusack BJ, Mushlin PS, Voulelis LD, Li X, Boucek RJ, Jr., Olson RD. Daunorubicin-induced cardiac injury in the rabbit: a role for daunorubicinol? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1993;118(2):177–185. doi: 10.1006/taap.1993.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cusack BJ, Musser B, Gambliel H, Hadjokas NE, Olson RD. Effect of dexrazoxane on doxorubicin pharmacokinetics in young and old rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51(2):139–146. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombo T, Donelli MG, Urso R, Dallarda S, Bartosek I, Guaitani A. Doxorubicin toxicity and pharmacokinetics in old and young rats. Exp Gerontol. 1989;24(2):159–171. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(89)90026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, et al. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91(5):710–717. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-5-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Licata S, Saponiero A, Mordente A, Minotti G. Doxorubicin metabolism and toxicity in human myocardium: role of cytoplasmic deglycosidation and carbonyl reduction. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13(5):414–420. doi: 10.1021/tx000013q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donelli MG, Zucchetti M, Munzone E, D’Incalci M, Crosignani A. Pharmacokinetics of anticancer agents in patients with impaired liver function. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sturgill MG, August DA, Brenner DE. Hepatic enzyme induction with phenobarbital and doxorubicin metabolism and myelotoxicity in the rabbit. Cancer Invest. 2000;18(3):197–205. doi: 10.3109/07357900009031824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preiss R, Matthias M, Sohr R, Brockmann B, Huller H. Pharmacokinetics of adriamycin, adriamycinol, and antipyrine in patients with moderate tumor involvement of the liver. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1987;113(6):593–598. doi: 10.1007/BF00390872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler JM, Begg EJ. Free drug metabolic clearance in elderly people. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(5):297–321. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmucker DL, Woodhouse KW, Wang RK, et al. Effects of age and gender on in vitro properties of human liver microsomal monooxygenases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1990;48(4):365–374. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1990.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sotaniemi EA, Arranto AJ, Pelkonen O, Pasanen M. Age and cytochrome P450-linked drug metabolism in humans: an analysis of 226 subjects with equal histopathologic conditions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;61(3):331–339. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Mimura M, Inui Y, Guengerich FP. Interindividual variations in human liver cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the oxidation of drugs, carcinogens and toxic chemicals: studies with liver microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270(1):414–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George J, Byth K, Farrell GC. Age but not gender selectively affects expression of individual cytochrome P450 proteins in human liver. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50(5):727–730. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Hong J, Cressman EN, Arriaga EA. Direct sampling from human liver tissue cross sections for electrophoretic analysis of doxorubicin. Anal Chem. 2009;81(9):3321–3328. doi: 10.1021/ac802542e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson AB, Ciriacks CM, Fuller KM, Arriaga EA. Distribution of zeptomole-abundant doxorubicin metabolites in subcellular fractions by capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. Anal Chem. 2003;75(1):8–15. doi: 10.1021/ac020426r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold RD, Slack JE, Straubinger RM. Quantification of doxorubicin and metabolites in rat plasma and small volume tissue samples by liquid chromatography/electrospray tandem mass spectroscopy. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;808(2):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi R, Goto S. Age-associated accumulation of heat-labile aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in mice and rats. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1987;6(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(87)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katzenmeyer JB, Eddy CV, Arriaga EA. Tandem laser-induced fluorescence and mass spectrometry detection for high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of the in vitro metabolism of doxorubicin. Anal Chem. 2010;82(19):8113–8120. doi: 10.1021/ac1011415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eder AR, Chen JS, Arriaga EA. Separation of doxorubicin and doxorubicinol by cyclodextrin-modified micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography. Electrophoresis. 2006;27(16):3263–3270. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takanashi S, Bachur NR. Adriamycin metabolism in man. Evidence from urinary metabolites. Drug Metab Dispos. 1976;4(1):79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gewirtz DA, Yanovich S. Metabolism of adriamycin in hepatocytes isolated from the rat and the rabbit. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36(11):1793–1798. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vrignaud P, Londos-Gagliardi D, Robert J. Hepatic metabolism of doxorubicin in mice and rats. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1986;11(2):101–105. doi: 10.1007/BF03189834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollak N, Dolle C, Ziegler M. The power to reduce: pyridine nucleotides—small molecules with a multitude of functions. Biochem J. 2007;402(2):205–218. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters MA, Fouts JR. A study of some possible mechanisms by which magnesium activates hepatic microsomal drug metabolism in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970;173(2):233–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King CD, Rios GR, Green MD, Tephly TR. UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Curr Drug Metab. 2000;1(2):143–161. doi: 10.2174/1389200003339171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Negishi M, Pedersen LG, Petrotchenko E, et al. Structure and function of sulfotransferases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;390(2):149–157. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santa Maria C, Machado A. Changes in some hepatic enzyme activities related to phase II drug metabolism in male and female rats as a function of age. Mech Ageing Dev. 1988;44(2):115–125. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(88)90084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galinsky RE, Johnson DH, Kane RE, Franklin MR. Effect of aging on hepatic biotransformation in female Fischer 344 rats: changes in sulfotransferase activities are consistent with known gender-related changes in pituitary growth hormone secretion in aging animals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255(2):577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wildiers H, Highley MS, de Bruijn EA, van Oosterom AT. Pharmacology of anticancer drugs in the elderly population. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(14):1213–1242. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.