Abstract

Background/Aims

Mutations in the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (SLC10A2) block intestinal bile acid absorption, resulting in a compensatory increase in hepatic bile acid synthesis. Inactivation of the basolateral membrane bile acid transporter (OSTα-OSTβ) also impairs intestinal bile acid absorption, but hepatic bile acid synthesis was paradoxically repressed. We hypothesized that the altered bile acid homeostasis resulted from ileal trapping of bile acids that act via the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) to induce overexpression of FGF15. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether blocking FXR signaling would reverse the bile acid synthesis phenotype in Ostα null mice.

Methods

The corresponding null mice were crossbred to generate OstαFxr double-null mice. All experiments compared wild-type, Ostα, Fxr and OstαFxr null littermates. Analysis of the in vivo phenotype included measurements of bile acid fecal excretion, pool size and composition. Hepatic and intestinal gene and protein expression were also examined.

Results

OstαFxr null mice exhibited increased bile acid fecal excretion and pool size, and decreased bile acid pool hydrophobicity, as compared with Ostα null mice. Inactivation of FXR reversed the increase in ileal total FGF15 expression, which was associated with a significant increase in hepatic Cyp7a1 expression.

Conclusions

Inactivation of FXR largely unmasked the bile acid malabsorption phenotype and corrected the bile acid homeostasis defect in Ostα null mice, suggesting that inappropriate activation of the FXR-FGF15-FGFR4 pathway partially underlies this phenotype. Intestinal morphological changes and reduced apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter expression were maintained in Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice, indicating that FXR is not required for these adaptive responses.

Key Words: Enterohepatic circulation, Intestine, Liver, Cholesterol, Villus

Introduction

Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and secreted with bile into the small intestine to facilitate absorption of dietary lipids. Bile acids are almost quantitatively reclaimed by the intestine (>95%) and transported back to the liver to be resecreted into bile. Efficient intestinal reabsorption and hepatic extraction of bile acids enables a very effective recycling and conservation mechanism that largely restricts these cytotoxic detergents to the intestinal and hepatobiliary compartments [1,2]. Since the early 1990s, many of the hepatic and intestinal transporters that function to maintain the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids have been identified [3,4].

In the ileum, the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (Asbt or ibat; gene symbol Slc10a2) mediates the uptake of bile acids from the gut lumen across the apical brush border membrane of the enterocyte. Considering the large flux of bile acids across the ileal enterocyte (approx. 25 mg/day in mice; approx. 20–30 g/day in humans) and that there is a dedicated apical carrier, it is likely that a dedicated basolateral bile acid transporter is also involved. More recently, the unusual heteromeric transporter Ostα-Ostβ was identified and shown to transport a variety of solutes, including bile acids and steroids [5]. Subsequently, several lines of evidence emerged that support a role for Ostα-Ostβ in the basolateral membrane transport of bile acids in the intestine, liver and kidney [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Targeted inactivation of Ostα in mice was associated with significantly decreased ileal absorption of bile acids, as demonstrated using everted gut sacs or by intraluminal administration of bile acids [12,15]. However, whereas hepatic bile acid synthesis and fecal bile acid excretion is typically elevated in patients with Asbt mutations [16] or in Asbt–/– mice [17,18], Ostα–/– mice exhibited decreased hepatic Cyp7a1 expression and no increase in fecal bile acid excretion. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is involved in the dysregulated bile acid metabolism and adaptive responses observed in Ostα–/– mice.

Results

Phenotype of Ostα–/–Fxr–/– Mice

Ostα–/– mice (in a mixed C57BL/6J-129/SvEv background) were generated as previously described by Rao et al. [12]. Fxr–/– mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (stock No.: 004144, strain: B6;129X(FVB)-Nr1h4tm1Gonz/J). The corresponding null mice were crossbred to generate Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice. The experiments were performed using wild-type, Ostα–/–, Fxr–/– and Ostα–/–Fxr–/– littermates in a mixed background, which were maintained on a rodent-chow diet. The Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice were viable and fertile. There was no obvious prenatal mortality in these backgrounds as crosses between heterozygous mice produced the predicted Mendelian distribution of wild-type and mutant genotypes. There were no significant differences in body weight or liver weight between the adult wild-type and Ostα–/– mice or between the Fxr–/– and Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice. As previously reported [12,15], the most significant morphological finding was a longer and heavier small intestine in Ostα–/– mice as compared with wild-type littermates. Specifically, the small intestine of adult male Ostα–/– mice (3 months of age) was approximately 18% longer and 46% heavier; similar results were observed for female Ostα–/– mice versus wild-type mice. Inactivation of FXR in Ostα–/– mice largely restored the small intestine to the wild-type length, but did not reverse the increase in the intestinal weight. The increased intestinal weight was particularly evident in distal small intestine of Ostα–/– and Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice.

Quantitative morphometric analyses were also performed to examine the effects of Ostα inactivation on small intestine. Histological evaluation revealed little change in proximal small intestine, but it did show a significantly thickened mucosa in ileum. Villus width and crypt depth were all significantly increased in ileum of Ostα–/– mice as compared with wild-type or Fxr–/– littermates. FXR deficiency did not reverse this phenotype in Ostα–/– mice, suggesting that bile acid signaling via this nuclear receptor is not responsible for the intestinal hyperplasia. These morphological changes were not accompanied by an increase in inflammatory cell infiltration. In addition, analysis of mRNA expression revealed no increases in expression of proinflammatory genes such as TNFα or IL-1β, or genes involved in ER stress such as X-box-binding protein-1 (Xbp1) or activating transcription factor-6 (Atf6) in ileum of Ostα–/– or Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice versus wild-type or Fxr–/– mice. The gene expression profile was consistent with the histological absence of intestinal inflammation and the lack of diarrhea in Ostα–/– and Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice.

Fecal Bile Acid Excretion and Pool Size in Ostα–/–Fxr–/– Mice

Inactivation of Ostα was predicted to induce bile acid malabsorption by blocking enterocyte basolateral membrane bile acid transport, a phenotype similar to that observed for a block in intestinal apical uptake of bile acids [16,17,18]. However, as previously reported [12,15], fecal bile acid excretion was not increased in Ostα–/– mice, despite an apparent block in intestinal bile acid absorption and a greater than 50% decrease in the bile acid pool size. Although this decrease in bile acid pool size was similar to that observed in Asbt–/– mice, the Ostα–/– mice exhibited a disproportionate decrease in the taurocholate fraction, yielding a more hydrophilic bile acid pool that is enriched in tauro-β-muricholate. This phenotype is in contrast with the Asbt–/– mice, where elevated hepatic bile acid synthesis via the Cyp7a1/Cyp8b1 pathway results in a bile acid pool that is significantly enriched in taurocholate.

The phenotype in Ostα–/– mice is consistent with a paradoxical downregulation of hepatic bile acid synthesis via the Cyp7a1 pathway. In light of the central role of the FXR-FGF15-FGFR4 pathway in regulation of Cyp7a1 and hepatic bile acid synthesis [19,20], we hypothesized that the altered bile acid homeostasis in Ostα–/– was secondary to increased activation of FXR and induction of FGF15 expression in ileum. In support of that hypothesis, FXR deficiency in Ostα–/– mice unmasked the underlying bile acid malabsorption phenotype, increasing fecal bile acid excretion by almost threefold in Ostα–/–Fxr–/– versus Ostα–/– mice.

The bile acid pool size was also partially restored following inactivation of FXR, increasing almost twofold in male and female Ostα–/–Fxr–/– versus Ostα–/– mice. However, the bile acid pool size was still reduced in Ostα–/–Fxr–/– versus Fxr–/– mice and wild-type mice, demonstrating that the increased hepatic bile acid synthesis cannot fully compensate for the decreased intestinal bile acid absorption as a result of inactivation of Ostα. FXR deficiency increased the proportion of taurocholate in the bile acid pool, as reflected by an increased calculated hydrophobicity of the bile acid pool in Ostα–/–Fxr–/– versus Ostα–/– mice. Overall, inactivation of FXR in Ostα–/– mice resulted in a bile acid phenotype that was more similar to the Asbt–/– than wild-type mice.

Expression of Hepatic and Intestinal Genes Involved in Bile Acid Metabolism in Ostα–/–Fxr–/– Mice

In agreement with the bile acid fecal excretion and pool size results, inactivation of FXR was associated with a dramatic induction of Cyp7a1 mRNA expression in the Ostα–/– mice. Hepatic expression of Cyp7a1 mRNA was increased almost eightfold in Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice as compared to Ostα–/– mice. A similar trend was observed for hepatic Cyp8b1 mRNA expression, which was increased almost fourfold. The gene expression changes appeared to be restricted to the classical bile acid biosynthetic pathway, as there were no changes in hepatic mRNA expression for Cyp27a1, a major enzyme in the alternative pathway.

Analysis of the gradient of FGF15 mRNA expression along the cephalocaudal axis of the small intestine revealed no major differences between the four genotypes, and FGF15 mRNA expression was largely restricted to distal small intestine. Contrary to the predicted mechanism for the decreased hepatic Cyp7a1 expression, ileal FGF15 mRNA expression (when normalized to expression of the housekeeping gene cyclophilin) was not significantly increased in Ostα–/– versus wild-type mice. However, total ileal FGF15 mRNA expression was increased almost threefold in Ostα–/– versus wild-type mice when the intestinal hyperplasia was considered and gene expression was normalized for the increased RNA content of the tissue. Inactivation of FXR dramatically reduced ileal cellular and total FGF15 mRNA expression in agreement with previous studies demonstrating an essential role of FXR in regulating FGF15 expression [19,20,21]. In Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice, ileal total FGF15 mRNA expression was reduced by approximately 90% as compared to Ostα–/– mice.

Although these results indicate that FXR is essential for the increased intestinal FGF15 expression, the finding that the FGF15 mRNA expression per cell was not increased suggests that bile acids do not accumulate within the enterocyte or that the cell is hyporesponsive to the bile acid load. In order to investigate those potential mechanisms, the cellular expression of other FXR-responsive genes was investigated. Ileal cellular mRNA expression of the FXR target genes Ibabp and Ostβ was significantly decreased in ileum from Ostα–/– mice. This apparent decrease in FXR activity may be secondary to the decreased bile acid pool size in Ostα–/– mice. However, another potential mechanism is decreased Asbt expression, which would function to limit the uptake and accumulation of cytotoxic bile acids in ileal enterocytes. In fact, ileal Asbt expression was found to be reduced by approximately 50% at the mRNA level and greater than 90% at the protein level in Ostα–/– mice. Notably, the dramatic reduction in Asbt mRNA and protein expression was maintained in Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice, indicating that FXR is not required for this adaptive response.

Discussion

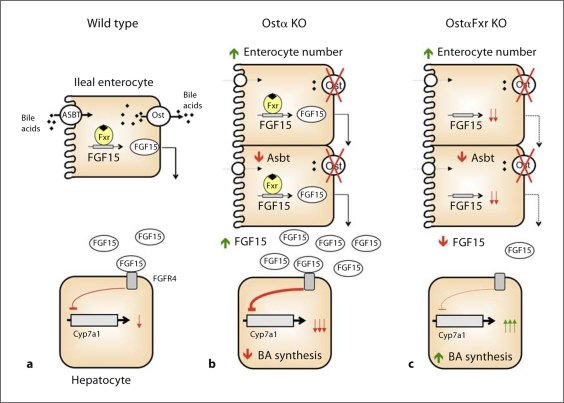

In this study, we examined the role of FXR in the altered regulation of bile acid metabolism in Ostα–/– mice. In summary, we demonstrated that FXR is essential for repression of Cyp7a1 expression in Ostα–/– mice. Genetic inactivation of FXR in Ostα–/– mice increased bile acid synthesis, reversed shifts in bile acid pool composition and restored intestinal cholesterol absorption. However, FXR deficiency failed to reverse the intestinal morphological changes in Ostα–/– mice. Moreover, it is not an enhanced activation of FXR that drives the increase in intestinal FGF15 expression, but rather a complex adaptive response that increases the ileal enterocyte population. In fact, a decrease in the bile acid pool size and significantly reduced ileal Asbt expression may function to protect the enterocytes in Ostα–/– mice from accumulating potentially cytotoxic levels of bile acids. These findings are consistent with a critical but limited role of FXR in the adaptive responses engaged to compensate for the loss of Ostα in mice. The current model depicting the hypothesized mechanism for regulation of bile acid homeostasis in wild-type, Ostα–/– and Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice is shown in figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Model depicting the regulation of ileal FGF15 synthesis and hepatic bile acid (BA) synthesis in wild-type, Ostα–/– and Ostα–/–Fxr–/– mice. Schematic model depicting the differential regulation of Cyp7a1. a Bile acids are absorbed from the intestinal lumen via Asbt and activate FXR to induce FGF15 expression. Ileal-derived FGF15 acts on the liver via its receptor, FGFR4, to repress Cyp7a1 expression and bile acid synthesis. b A reduction in the bile acid pool size and decreased Asbt expression reduces the accumulation of bile acids in the ileal enterocytes. However, ileal hyperplasia leads to an increase in the number of FGF15-expressing enterocytes. As a result, the total intestinal FGF15 expression is increased and signals to repress hepatic Cyp7a1 expression and bile acid synthesis. c Inactivation of FXR does not reverse the downregulation of Asbt expression or intestinal morphological changes in the Ostα–/– mice. However, inactivation of FXR significantly reduces ileal FGF15 expression. As a result, the total intestinal FGF15 expression is reduced, and hepatic Cyp7a1 expression and bile acid synthesis is increased.

These results generally support a significant role for Ostα-Ostβ in intestinal basolateral bile acid transport. However, many questions remain to be answered, particularly with regard to the complex intestinal adaptive response in Ostα–/– mice. This intestinal phenotype is not a general response to bile acid malabsorption, as similar changes in intestinal morphology were not observed in Asbt–/– or Mrp3–/– mice [17,18,22]. Nor does the intestinal adaptation appear to be a direct response to bile acid toxicity, as neither bile acid accumulation nor intestinal inflammation were observed in Ostα–/– mice. The finding that inactivation of FXR failed to reverse the intestinal adaptive response indicates that the changes are not mediated through increased bile acid signaling via this nuclear receptor. As such, other mechanisms such as the accumulation of non-bile acid substrates may be involved. Ostα-Ostβ has been shown to transport other solutes, such as steroids and steroid sulfates [23], and enhanced signaling due to accumulation of these substrates may be involved in promoting intestinal growth in Ostα–/– mice.

In conclusion, activation of the FXR-FGF15-FGFR4 pathway is essential for the altered bile acid homeostasis associated with genetic ablation of the intestinal basolateral bile acid transporter Ostα-Ostβ. Surprisingly, a complex adaptive response that increases the ileal enterocyte population largely accounts for the increase in total intestinal FGF15 expression in Ostα–/– mice rather than increased bile acid accumulation and FXR activation.

Disclosure Statement

P.A.D. has served on the Scientific Advisory Board and owns equity in XenoPort Inc. He has also served as a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Isis Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb. T.L., J.H. and A.R. have no conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by NIH DK047987 and an American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate grant-in-aid (to P.A.D.). A.R. is supported by a National Research Service Award (F32 DK079576) from the NIDDK.

References

- 1.Hofmann AF, Hagey LR. Bile acids: chemistry, pathochemistry, biology, pathobiology, and therapeutics. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2461–2483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmann AF. Bile acids: trying to understand their chemistry and biology with the hope of helping patients. Hepatology. 2009;49:1403–1418. doi: 10.1002/hep.22789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alrefai WA, Gill RK. Bile acid transporters: structure, function, regulation and pathophysiological implications. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1803–1823. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson PA, Lan T, Rao A. Bile acid transporters. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2340–2357. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900012-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seward DJ, Koh AS, Boyer JL, Ballatori N. Functional complementation between a novel mammalian polygenic transport complex and an evolutionarily ancient organic solute transporter, OSTalpha-OSTbeta. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27473–27482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H, Zhang Y, Lee FY, Nelson SF, Gonzalez FJ, Edwards PA. FXR regulates organic solute transporters alpha and beta in the adrenal gland, kidney, and intestine. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:201–214. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500417-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankenberg T, Rao A, Chen F, Haywood J, Shneider BL, Dawson PA. Regulation of the mouse organic solute transporter alpha-beta, Ostalpha-Ostbeta, by bile acids. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G912–G922. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00479.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landrier JF, Eloranta JJ, Vavricka SR, Kullak-Ublick GA. The nuclear receptor for bile acids, FXR, transactivates human organic solute transporter-alpha and -beta genes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G476–G485. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00430.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer JL, Trauner M, Mennone A, et al. Upregulation of a basolateral FXR-dependent bile acid efflux transporter OSTalpha-OSTbeta in cholestasis in humans and rodents. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1124–G1130. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00539.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson PA, Hubbert M, Haywood J, et al. The heteromeric organic solute transporter alpha-beta, Ostalpha-Ostbeta, is an ileal basolateral bile acid transporter. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6960–6968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412752200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballatori N, Christian WV, Lee JY, et al. OSTalpha-OSTbeta: a major basolateral bile acid and steroid transporter in human intestinal, renal, and biliary epithelia. Hepatology. 2005;42:1270–1279. doi: 10.1002/hep.20961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao A, Haywood J, Craddock AL, Belinsky MG, Kruh GD, Dawson PA. The organic solute transporter alpha-beta, Ostalpha-Ostbeta, is essential for intestinal bile acid transport and homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3891–3896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712328105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soroka CJ, Mennone A, Hagey LR, Ballatori N, Boyer JL. Mouse organic solute transporter alpha deficiency enhances renal excretion of bile acids and attenuates cholestasis. Hepatology. 2010;51:181–190. doi: 10.1002/hep.23265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson PA, Hubbert ML, Rao A. Getting the mOST from OST: Role of organic solute transporter, OSTalpha-OSTbeta, in bile acid and steroid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:994–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballatori N, Fang F, Christian WV, Li N, Hammond CL. Ostalpha-Ostbeta is required for bile acid and conjugated steroid disposition in the intestine, kidney, and liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G179–G186. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90319.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oelkers P, Kirby LC, Heubi JE, Dawson PA. Primary bile acid malabsorption caused by mutations in the ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter gene (SLC10A2) J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1880–1887. doi: 10.1172/JCI119355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung D, Inagaki T, Gerard RD, et al. FXR agonists and FGF15 reduce fecal bile acid excretion in a mouse model of bile acid malabsorption. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2693–2700. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700351-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawson PA, Haywood J, Craddock AL, et al. Targeted deletion of the ileal bile acid transporter eliminates enterohepatic cycling of bile acids in mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33920–33927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;2:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim I, Ahn SH, Inagaki T, et al. Differential regulation of bile acid homeostasis by the farnesoid X receptor in liver and intestine. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2664–2672. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700330-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroeve JH, Brufau G, Stellaard F, Gonzalez FJ, Staels B, Kuipers F. Intestinal FXR-mediated FGF15 production contributes to diurnal control of hepatic bile acid synthesis in mice. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1457–1467. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belinsky MG, Dawson PA, Shchaveleva I, et al. Analysis of the in vivo functions of Mrp3. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:160–168. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballatori N, Li N, Fang F, Boyer JL, Christian WV, Hammond CL. OST alpha-OST beta: a key membrane transporter of bile acids and conjugated steroids. Front Biosci. 2009;14:2829–2844. doi: 10.2741/3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]