Abstract

Background

Midbrain atrophy is a well-known feature of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). Some clinical features of vascular parkinsonism (VP) such as pseudobulbar phenomena, lower body predominance and early postural instability suggest that the brainstem could be associated with VP. The aim of this study was to determine whether midbrain atrophy was present in patients with VP.

Methods

We measured the midbrain (Amd) and pons area (Apn) of 20 patients with VP, 15 patients with probable PSP and 30 patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD). The Amd and Apn were measured on mid-sagittal T1-weighted MRI scans using a computerized image analysis system.

Results

For the Amd, the patients with VP (99.86 mm2) and PSP (87.30 mm2) had significantly smaller areas than the patients with IPD (130.52 mm2). For the Apn, there was a significant difference only between the VP (407.23 mm2) and the IPD (445.05 mm2) patients. The Amd/Apn ratios of the patients with VP (0.245) and PSP (0.208) were significantly smaller than in the patients with IPD (0.292).

Conclusions

Our study shows that brainstem atrophy often occurs in patients with VP and the midbrain is more vulnerable than the pons to atrophic changes.

Key Words: Vascular parkinsonism, Progressive supranuclear palsy, MRI, Atrophy, Brainstem

Introduction

Parkinsonism has a variety of etiologies. In addition to the idiopathic occurrence, it can also be caused by toxins, drugs, trauma, stroke, as well as metabolic and genetic disorders. After Critchley's original report on arteriosclerotic parkinsonism, at a time when the etiology of idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD) was not fully understood [1], it has been shown that vascular parkinsonism (VP) is a distinct heterogeneous clinical entity among the parkinsonian syndromes [2]. The clinical features of VP vary and the brain imaging findings used to diagnose VP have not been clearly established.

Hyperintense white matter lesions on T2-weighted images were more common in patients with VP compared with those of IPD [3]. The presence of vascular disease in two or more vascular territories on brain imaging supports the diagnosis of VP but does not establish a cause-and-effect relationship. Apparently, similar vascular lesions noted on brain imaging may be associated with parkinsonism in some patients but not in others [4].

Brainstem atrophy was more common in patients with parkinsonian syndromes compared with patients with IPD [3]. Midbrain atrophy is a well-known feature of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) [5,6,7,8]. A lot of previous reports have suggested that measurements for diameters and areas of midbrain and pons on routine MRIs are valuable in discriminating PSP from either IPD or multiple system atrophy [5,6,8,9]. In addition to PSP, some studies have shown that patients with vascular dementia (VaD) also had midbrain atrophy on MRIs [10,11]. Some of the characteristics of VP and VaD overlap – both have the frequent occurrence of brain atrophy, white matter lesions and a predominance of motor symptoms such as gait disturbances [12]. Furthermore, several clinical features of VP such as early postural instability, pseudobulbar phenomena, and lower body predominance suggest that brainstem atrophy could be associated with VP.

The aim of this study was to determine whether midbrain atrophy, measured by morphometric MRI, was present in patients with clinically diagnosed VP in comparison to patients with PSP and IPD.

Methods

Subjects

Parkinsonism was defined by the presence of bradykinesia and at least one of the following: muscular rigidity, 4–6 Hz rest tremor, and postural instability not caused by primary visual, vestibular, cerebellar, or proprioceptive dysfunction [13]. The clinical diagnoses of IPD and probable PSP were based on the UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank clinical diagnostic criteria for PD [13] and the clinical criteria of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Society for Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (NINDS-SPSP) [14]. Some PSP patients had only vertical gaze slowing at the time of initial examination, but eventually showed vertical gaze palsy at follow-up. All PSP patients were compatible with Richardson's syndrome [15]. The diagnosis of VP was based on those previously published [3,16,17,18], which include lower body predominance, frontal gait disorder, muscle rigidity, no resting tremor, symmetric progression, postural instability, and poor response to levodopa. The patients were considered dopa-responsive when levodopa reduced scores of the modified Hoehn & Yahr stage by >0.5. All VP patients had evidence of relevant cerebrovascular disease on brain MRI using a previously described approach [16] and all patients with IPD and PSP did not have significant cerebrovascular lesions. We also used a modified Fazekas scale [19] to quantify the vascular lesion load in the VP patients and in the patients of the other groups (table 1). Two neurologists (J.T.K, M.S.P.), blinded to clinical diagnosis, rated signal abnormalities on T2-weighted and FLAIR images. The intraclass correlation coefficients for inter-rater reliability was good (κ scores = 0.81–0.93). The incidence and extent of white matter hyperintensity and basal ganglia lesion in the VP patients were higher and greater than those in the patients of the other groups. In clinical practice, it is clinically difficult to separate between vascular PSP and neurodegenerative PSP [3]. For the diagnostic accuracy of VP, we excluded the VP patients who showed evidence of slowing or palsy of saccadic eye movements. Also patients with a history of repeated head trauma, encephalitis, brain surgery, neuroleptic treatment at onset of symptoms, presence of cerebral tumor or hydrocephalus on MRI scan, or other alternative causes for parkinsonism were excluded. All patients received full neurologic evaluations by a movement disorder specialist (S.M.C.).

Table 1.

Incidence and extent of MR abnormalities in Parkinson's disease, VP and PSP

| IPD (n = 30) | VP (n = 20) | PSP (n = 15) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periventricular white matter hyperintensity | ||||

| With lesions, n (%) | 24 (80.0) | 20 (100) | 10 (66.6) | |

| Score, mean ± SD | 0.8±0.4 | 2.3±0.8 | 0.7±0.4 | <0.001a |

| Deep white matter hyperintensity | ||||

| With lesions, n (%) | 12 (40.0) | 20 (100) | 7 (46.6) | |

| Score, mean ± SD | 0.4±0.3 | 2.0±0.8 | 0.4±0.4 | <0.001a |

| Basal ganglia foci | ||||

| With lesions, n (%) | 8(26.6) | 18(90.0) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Number, mean ± SD | 0.3±0.5 | 1.7±0.7 | 0.2±0.3 | <0.001a |

| Cortical hyperintensity | ||||

| With lesions, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Number, mean ± SD | 0±0 | 0.1±0.3 | 0±0 | NS |

IPD = Idiopathic Parkinson's disease; VP = vascular parkinsonism; PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy; NS = not significant; SD = standard deviation.

Significant difference between the VP group and the IPD group (p < 0.001) and between the VP group and the PSP group (p < 0.001).

We enrolled patients visiting the Neurology Clinic at Chonnam National University Hospital (CNUH), who fulfilled the above-mentioned criteria, retrospectively. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants and the study was approved by the CNUH Institutional Review Board. All participants received full neurological and physical examinations, routine laboratory tests, and the Korean version of Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE).

MRI Analysis of the Midbrain and Pons

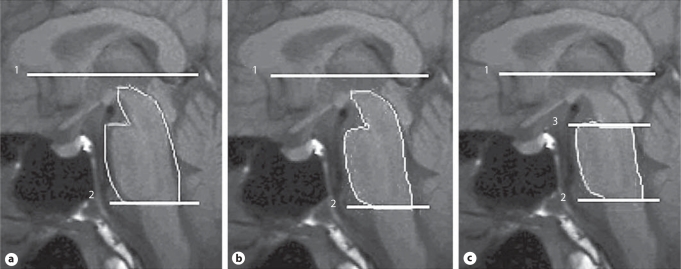

All MRI studies were carried out on a 1.5-T GE Signar LS imager (General Electric, Milwaukee, Wisc., USA). All subjects received a diagnostic MRI with sagittal T1-weighted images (TR = 420 ms, TE = 14 ms; acquisition matrix = 320 × 224; section thickness = 4 mm), axial T1-weighted images and axial T2-weighted images. The quantitative data was derived by semi-automated methods. The images were transferred to a Sun SPARC workstation (Sun Microsystems, Mountain View, Calif., USA), and analyzed with Multimodal Image Data Analysis System (MIDAS) software [20]. According to a modified Kato's procedure [6], the line connecting the base of the genu and splenium of the corpus callosum was set horizontally (fig. 1a–c, line 1). Lines 2 and 3 were marked parallel to line 1. After drawing the horizontal border between the pons and medulla at the lower end of the pons (line 2), we roughly drew a region of interest (ROI) that contained all of the midbrain and pons as well as the adjacent cerebrospinal fluid (fig. 1a). After the intensity normalization of the individual scan, we defined the intensity threshold for the extraction of brainstem segmentation from the ROI (fig. 1b). The remaining area was the midbrain plus pons. After drawing the horizontal border between the midbrain and pons at the upper end of the pons (line 3), we obtained the pons area by excluding the midbrain area (fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Scheme for the measurement of the Amd and Apn on mid-sagittal MRI (a–c). Line 1 connects the base of the genu and splenium of the corpus callosum. Lines 2 and 3 are parallel to line 1. Line 2 is at the level of the lower end of the pons. Line 3 is at the level of the upper end of the pons. a ROI of the figure was drawn manually. b ROI of the figure was drawn automatically using signal intensity difference between brainstem and cerebrospinal fluid. c After drawing the horizontal border between the midbrain and pons at the upper end of the pons (line 3), the Apn was obtained by excluding the Amd.

All imaging processing steps were performed by one neurologist (B.C.K.) who was blind to all clinical information. We measured the areas of the midbrain (Amd) and pons (Apn), and calculated the ratio of the midbrain area to the pons area (Amd/Apn).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical software SPSS version 11.5 for Windows was used for all statistical analyses. The χ2 test for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for continuous variables were used to analyze the demographic and clinical variables among the three groups. The ANOVA test was also used to compare MRI variables (Amd, Apn and Amd/Apn) among the individual groups, and Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. The results were considered statistically significant at a p value <0.05.

Results

Thirty patients with IPD, 20 patients with VP, and 15 patients with probable PSP were included in this study from January 2005 through June 2008. There were no significant differences among the three groups with regard to gender, age of symptom onset, age at MRI, and time interval from symptom onset to MRI. There were significant differences among the three groups of patients in Hoehn & Yahr stage and mean K-MMSE score (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic data and clinical features of the patients with IPD, VP, and PSP

| IPD (n = 30) | VP (n = 20) | PSP (n = 15) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 19/11 | 12/8 | 11/4 | NS |

| Age at symptom onset, years | 67.2±5.8 | 69.0±6.2 | 64.1 ±5.6 | NS |

| Age at MRI, years | 68.6±5.6 | 70.4±6.6 | 65.6±6.1 | NS |

| Time interval from symptom onset to MRI, years | 1.8± 1.3 | 1.7± 1.4 | 2.0 ±1.7 | NS |

| Hoehn & Yahr stage | 1.5±0.63 | 3.0 ±0.61 | 3.1 ±1.5 | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 26.1±2.3 | 18.9±3.1 | 22.±±4.5 | <0.001 |

IPD = Idiopathic Parkinson's disease; VP = vascular parkinsonism; PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy; NS = not significant. p value by ANOVA.

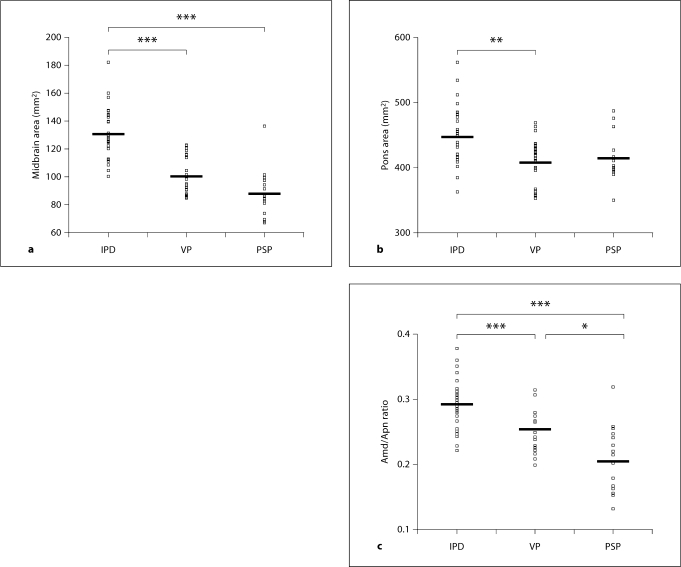

The comparisons, by ANOVA, for the mean value of the Amd, Apn, and the Amd/Apn among the three patient groups, were statistically significant. The Amd was 130.52 ± 17.89 mm2 in the IPD patients, 99.86 ± 13.36 mm2 in the VP patients, and 87.30 ± 17.77 mm2 in the PSP patients. The statistical analysis revealed that there were significant differences in the Amd between the IPD patients and the VP patients (p < 0.001) or the PSP patients (p < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in the Amd between the VP patients and the PSP patients (p = 0.091) (fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of the Amd (a) and the Apn (b) and the Amd/Apn (c) in the patients with IPD, VP, and PSP. The Amd in the patients with VP and PSP differed significantly from the same area in the patients with IPD. The Apn in the patients with VP differed significantly from the same area in the patients with IPD. The ratios in the patients with VP and PSP differed significantly from those in the patients with IPD. In addition, the ratio differed significantly between the patients with VP and those with PSP. ∗∗∗ p < 0.001; ∗∗ p < 0.01; ∗ p < 0.05; bar is mean value.

The Apn was 445.05 ± 45.56 mm2 in the IPD patients, 407.23 ± 36.65 mm2 in the VP patients, and 415.36 ± 35.52 mm2 in the PSP patients. The statistical analysis revealed that there was a significant difference in the Apn between the IPD patients and VP patients (p = 0.006). However, there was no significant difference in the Apn between the PSP patients and IPD patients (p = 0.075) or the VP patients (p = 1.000) (fig. 2b).

The Amd/Apn was 0.293 ± 0.037 in the IPD patients, 0.246 ± 0.031 in the VP patients, and 0.208 ± 0.051 in the PSP patients. The statistical analysis revealed that there were significant differences in the ratios between the IPD patients and VP patients (p < 0.001) or the PSP patients (p < 0.001). In addition, there was a significant difference in the ratio between the VP patients and PSP patients (p = 0.021) (fig. 2c).

Discussion

The results of our study show that, in the VP patients, the Amd and Apn were smaller than they were in the IPD patients. In addition, the Amd/Apn of VP patients was smaller than in the IPD patients and larger than in the PSP patients. Therefore, brainstem atrophy appears to occur often in VP patients, and the midbrain is more vulnerable than the pons to atrophic changes. Our findings correlate with some clinical features such as pseudobulbar phenomena, predominantly lower body signs and are less responsive to levodopa in VP.

Midbrain atrophy is a typical neuropathological feature of PSP [21]. The MRI features of the brainstem are closely related to the histological findings of PSP [22]. However, the methods used to evaluate midbrain atrophy on MRI vary, and some methods are not accurate enough for the objective evaluation of midbrain atrophy because they lack reproducibility [23,24]. The axial MRI is not accurate and objective for the evaluation of midbrain atrophy because the measurement values vary according to the scanning angle. However, the mid-sagittal MRI can precisely show atrophic changes that are reproducible by objective measurements which are not subject to the influence of the scanning angle [8,25]. In this study, we used the mid-sagittal image for the measurements of the areas of interest, and also used a semi-automatic computerized system for circumscribing the boundary of the midbrain and the pons to complement any defects of the manual tracing.

There were no significant differences of the Amd and Apn between IPD and control in previous studies [8,9]. So we used IPD patients as control for the comparison of brainstem areas. The atrophy of the midbrain relative to the pons, in the PSP patients, was similar to the findings of a previous study [8]. In the patients with multiple system atrophy of the Parkinson type, atrophy of the pons has been reported to be a more common finding [8]. Therefore, the pattern of the brainstem atrophy can be useful in the differential diagnosis of parkinsonism. This is the first report on the pattern of brainstem atrophy in patients with VP and the results of our study can be used to help differentiate patients with parkinsonian syndromes.

The interpretation of the midbrain atrophy in VP patients should be considered with caution. There are several possible reasons for midbrain atrophy. First, the midbrain structures may be involved in the pathophysiology of VP. In patients with VP, brainstem and cerebellar involvement have been previously reported on MRI [3], and degenerative changes in the ipsilateral substantia nigra could occur 2 weeks after a striatal stroke [26]. Second, the midbrain atrophy could be related to global cortical atrophy, most probably attributable to axonal degeneration secondary to supratentorial pathology [10]. The association of midbrain atrophy and cognitive performance, in VaD patients, supports this hypothesis [10]. We are not able to conclude whether midbrain atrophy is related to parkinsonism or to axonal degeneration. To elucidate if midbrain atrophy has a role in parkinsonian symptom manifestations, it may be useful to add a further group of patients that includes matched patients for vascular lesion load but without parkinsonism. Our findings could be interpreted as midbrain atrophy which occurs more frequently in those subjects who have parkinsonism with vascular changes. More work is needed to determine the cause of midbrain atrophy in patients with VP.

This study has several limitations. We used clinical criteria for the diagnosis of IPD, PSP and VP, and did not have pathological confirmation. The diagnosis of VP was made using operational clinical criteria, which needs a validation study. The number of subjects was limited. In addition, there were large overlaps of the area and the ratio among the three diseases. This can limit the interpretation of the results. Further studies with pathological confirmation and larger groups of patients are needed to determine the diagnostic values accurately.

In conclusion, the midbrain was selectively atrophied in the patients with VP and PSP when compared to the patients with IPD; the midbrain atrophy was less severe in the patients with VP than in the patients with PSP. Therefore, midbrain atrophy and the Amd/Apn ratio, on mid-sagittal MRI, may help differentiate VP from IPD and PSP.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant (CRI09065-1) of the Chonnam National University Hospital Research Institute of Clinical Medicine.

References

- 1.Critchley M. Arteriosclerotic parkinsonism. Brain. 1929;52:23–83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demirkiran M, Bozdemir H, Sarica Y. Vascular parkinsonism: a distinct, heterogenous clinical entity. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;104:63–67. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.104002063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winikates J, Jankovic J. Clinical correlates of vascular parkinsonism. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:98–102. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thanvi B, Lo N, Robinson T. Vascular parkinsonism – an important cause of parkinsonism in older people. Age Ageing. 2005;34:114–119. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosottini M, Ceravolo R, Faggioni L, Lazzarotti G, Michelassi MC, Bonucelli U, Murri L, Bartolozzi C. Assessment of midbrain atrophy in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy with routine magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato N, Arai K, Hattori T. Study of the rostral midbrain atrophy in progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol Sci. 2003;210:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yagishita A, Oda M. Progressive supranuclear palsy: MRI and pathological findings. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:S60–S66. doi: 10.1007/BF02278121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oba H, Yagishita A, Terada H, Barkovich AJ, Kutomi K, Yamauchi T, Furui S, Shimizu T, Uchigata M, Matsumura K, Sonoo M, Sakai M, Takada K, Harasawa A, Takeshita K, Kohtake H, Tanaka H, Suzuki S. New and reliable MRI diagnosis for progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 2005;64:2050–2055. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165960.04422.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quattrone A, Nicoletti G, Messina D, Fera F, Condino F, Pugliese P, Lanza P, Barone P, Morgante L, Zappia M, Aguglia U, Gallo O. MR imaging index for differentiation of progressive supranuclear palsy from Parkinson disease and the Parkinson variant of multiple system atrophy. Radiology. 2008;246:214–221. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2453061703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bastos Leite AJ, van der Flier WM, van Straaten EC, Scheltens P, Barkhof F. Infratentorial abnormalities in vascular dementia. Stroke. 2006;37:105–110. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000196984.90718.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung YH, Park KH, Lee YB, Park HM, Shin DJ, Park JS, Oh MS, Ma HI, Yu KH, Kang SY, Kim YJ, Lee BC. Midbrain atrophy in subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. J Neurol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5226-z. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rektor I, Rektorova I, Kubova D. Vascular parkinsonism – an update. J Neurol Sci. 2006;248:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibb WR, Lees AJ. The relevance of Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:745–752. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litvan I, Agid Y, Calne D, Campbell G, Dubois B, Duvoisin RC, Goetz CG, Golbe LI, Grafman J, Growdon JH, Hallett M, Jankovic J, Quinn NP, Tolosa E, Zee DS. Clinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome): report of the NINDS-SPSP international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47:1–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DR, de Silva R, Paviour DC, Pittman A, Watt HC, Kilford L, Holton JL, Revesz T, Lees AJ. Characteristics of two distinct clinical phenotypes in pathologically proven progressive supranuclear palsy: Richardson's syndrome and PSP parkinsonism. Brain. 2005;128:1247–1258. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zijlmans JC, Daniel SE, Hughes AJ, Révész T, Lees AJ. Clinicopathological investigation of vascular parkinsonism, including clinical criteria for diagnosis. Mov Disord. 2004;19:630–640. doi: 10.1002/mds.20083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ondo WG, Chan LL, Levy JK. Vascular parkinsonism: clinical correlates predicting motor improvement after lumbar puncture. Mov Disord. 2002;17:91–97. doi: 10.1002/mds.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okuda B, Kawabata K, Tachibana H, Kamogawa K, Okamoto K. Primitive reflexes distinguish vascular parkinsonism from Parkinson's disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:562–565. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–356. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsui WH, Rusinek H, Wan Gelder P, Lebedev S. Analyzing multi-modality tomographic images and associated regions of interest with MIDAS. SPIE Medical Imaging: Imaging Processing. 2001;4322:1725–1734. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lantos PL. The neuropathology of progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1994;42:137–152. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6641-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aiba I, Hashizume Y, Yoshida M, Okuda S, Murakami N, Ujihira N. Relationship between brainstem MRI and pathologic findings in progressive supranuclear palsy: study in autopsy cases. J Neurol Sci. 1997;152:210–217. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masucci EF, Borts FT, Perl SM, Wener L, Schwankhaus J, Kurtzke JF. MR vs. CT in progressive supranuclear palsy. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1995;19:361–368. doi: 10.1016/0895-6111(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warmuth-Metz M, Naumann M, Csoti I, Solymosi L. Measurement of the midbrain diameter on routine magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1076–1079. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.7.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schonfeld SM, Globe LI, Sage JI, Sager JN, Duvoisin RC. Computed tomographic findings in progressive supranuclear palsy: correlation with clinical grade. Move Disord. 1987;2:263–278. doi: 10.1002/mds.870020404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakane M, Teraoka A, Asota R, Tamura A. Degeneration of the ipsilateral substantia nigra following cerebral infarction in the striatum. Stroke. 1992;23:328–332. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]