Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of specific personality disorder co-morbidity on the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally-representative sample.

Method

Data were drawn from 1,996 participants in a national survey. Participants who met criteria for major depressive disorder at baseline in face-to-face interviews (2001–2002) were re-interviewed three years later (2004–2005) to determine persistence and recurrence. Predictors included all DSM-IV personality disorders. Control variables included demographic characteristics, other Axis I disorders, family and treatment histories, and previously established predictors of the course of major depressive disorder.

Results

15.1% of participants had persistent major depressive disorder and 7.3% of those who remitted had a recurrence. Univariate analyses indicated that avoidant, borderline, histrionic, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders all elevated the risk for persistence. With Axis I co-morbidity controlled, all but histrionic personality disorder remained significant. With all other personality disorders controlled, borderline and schizotypal remained significant predictors. In final, multivariate analyses that controlled for age at onset of major depressive disorder, number of previous episodes, duration of current episode, family history, and treatment, borderline personality disorder remained a robust predictor of major depressive disorder persistence. Neither personality disorders nor other clinical variables predicted recurrence.

Conclusions

In this nationally-representative sample of adults with major depressive disorder, borderline personality disorder robustly predicted persistence, a finding that converges with recent clinical studies. Personality psychopathology, particularly borderline personality disorder, should be assessed in all patients with major depressive disorder, considered in prognosis, and addressed in treatment.

Major depressive disorder is highly prevalent (1), co-morbid with other mental disorders (2), and a leading source of disease burden worldwide (3). Prospective, longitudinal studies of patient samples show that major depressive disorder is a chronic illness, characterized by complex patterns of persistence, remission, and recurrence (4, 5). Similarly, the treatment literature characterizes the disorder as a refractory illness, presenting challenges for both clinicians and researchers (6).

Chronicity may be represented by prolonged time to recovery from an index episode (i.e., persistence) or by the occurrence of a new episode in a remitted case (i.e., relapse or recurrence). Identifying consistent predictors of the course of major depressive disorder (i.e., of remission, relapse, or persistence) has been difficult (4, 5). Recurrent disorder and number of prior episodes are associated with delayed remissions and accelerated relapses (7, 8). Patients with major depressive disorder and co-occurring dysthymic disorder (i.e., “double depression”) have more chronic courses than those without (9, 10). Other Axis I disorder co-morbidity (11), early onset (12), and female gender (13) are also predictors of chronicity, although not in all studies (5).

Personality disorders have received increasing attention as prognostic factors for the course and outcome of major depressive disorder. Critical reviews of naturalistic (14) and treatment (15) studies suggest that personality disorders have a negative impact on course. This literature is also mixed, however, and disparate findings likely reflect methodological limitations, including cross-sectional and retrospective rather than longitudinal and prospective designs, short-term follow-up intervals, assessment of few personality disorders, lack of standardized diagnostic interviews, and sample sizes insufficient to allow for multivariate analyses controlling for potentially confounding variables.

The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS) (16) was designed to provide comprehensive data on the course and outcome of patients with personality disorders, many of whom had major depressive disorder, and a comparison group of patients with major depressive disorder but no personality disorder. In initial two-year analyses, personality disorders predicted slower remission from major depressive disorder, even when controlling for other negative prognostic predictors (gender, ethnicity, Axis I co-morbidity, dysthymic disorder, recurrence, age of onset, and treatment) (17). More recent 6-year follow-up CLPS analyses extended these remission results and found that among those whose major depressive disorder remitted, patients with borderline and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders had shorter time to relapse than patients without personality disorders (18).

Although prospective studies of patient samples such as CLPS provide important information, patient studies may be biased by numerous confounds and selection factors (19). To better understand the course of major depressive disorder and its predictors, prospective epidemiological studies are needed. To our knowledge, no such study has been conducted. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to examine the effects of specific personality disorder co-morbidity on the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally-representative sample. The National Epidemiological Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions (NESARC) is a two-wave, face-to-face survey of more than 43,000 adults in the United States (20, 21). The three-year follow-up interview of the large NESARC sample provides the opportunity to determine the rates of persistence and recurrence of major depressive disorder in the community and the specific effects of all DSM-IV personality disorders on its course, while allowing for multivariate analyses to account for other potential predictors of chronicity. These data present a unique opportunity to confirm the hypothesis generated in clinical populations (17, 18) that personality disorders exert a strong, independent negative impact on the course of major depressive disorder.

Method

Participants

Participants were 1,996 respondents in Waves 1 and 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (20, 21). The target population was the civilian non-institutionalized population 18 years and older residing in households and group quarters (e.g., college quarters, group homes, boarding houses, and non-transient hotels). Blacks, Hispanics, and adults ages 18–24 were over-sampled, with data adjusted for over-sampling, household- and person-level non-response. Of the 43,093 respondents interviewed at Wave 1, census-defined eligible respondents for Wave 2 re-interviews included those not deceased (N=1403); deported, mentally or physically impaired (N=781); or on active military duty (N=950). In Wave 2, 34,653 of 39,959 eligible respondents were re-interviewed, for a response rate of 86.7%. Sample weights were developed to additionally adjust for Wave 2 non-response (21). At Wave 1, 2,422 respondents met criteria for current DSM-IV major depressive disorder. Of these, 1,996 participated in Wave 2 and constitute the present sample. Comparing the 1,996 re-interviewed to the 426 not re-interviewed on predictors and covariates described below, lower follow-up likelihood was predicted by race/ethnicity (Black, t=−3.08, df=5, p=0.003; Asian, t=−3.00, df=5, p=0.004; Hispanic, t=−2.60, df=5, p=0.01); less than college education (t=−3.24, df=2, p=0.002); unmarried status (t=−3.21, df=2, p=0.002); and dysthymic disorder (t=−2.60, df=2, p=0.01); but not age; gender; any substance use disorder; any anxiety disorder; any Axis II disorder; family history of depressive, alcohol, drug, or antisocial personality disorders; age at onset; or current treatment for depression. Of the sample of 1,996, 67.5% were female, 74.1% white, 9.1% black, 10.0% Hispanic, 3.8% Native American, and 3.1% Asian. Approximately one-quarter (26.9%) were <30 years old at Wave 1, 20.1% were 30–39, 24.7% were 40–49, and 27.9% were 50 or older. 49.9% were married or living with someone as if married and 56.6% had at least a high school education.

Procedures

In-person interviews were conducted by experienced lay interviewers with extensive training and supervision (20, 21). All procedures, including informed consent, received full ethical review and approval from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

Assessment and Variables

Interviewers administered the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) (22), a structured diagnostic interview developed to assess substance use and other mental disorders in large-scale surveys. Computer algorithms produced diagnoses of DSM-IV Axis I disorders and all DSM-IV personality disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Major depressive disorder was defined has having at least one major depressive episode over the life course without a history of manic, mixed, or hypomanic episodes. Diagnoses additionally required meeting clinical significance criteria (i.e., distress or impairment), having a “primary” mood disorder (excluding substance-induced or general medical conditions), and ruling out bereavement (1).

At Wave 1, criteria for a major depressive episode were assessed in two time frames: 1) current, i.e., during the last 12 months; and 2) prior to the last 12 months. At Wave 2, three years later, these criteria were again assessed in two time frames covering the entire time period between Waves 1 and 2: 1) current, last 12 months; and 2) prior to last 12 months, but since Wave 1. From these data, two outcome variables were created. Persistent major depressive disorder was defined as meeting full criteria for current disorder at Wave 1, and full criteria for major depressive disorder throughout the entire three-year follow-up, without the occurrence of mania. Recurrent major depressive disorder was defined as meeting full criteria at Wave 1 and again during the last 12 months at Wave 2, but not during the first 24 months after the Wave 1 interview.

The AUDADIS has good test-retest reliability for major depressive disorder (K=0.65–0.73) in clinical and general population samples (23, 24). Importantly, clinical reappraisals showed that AUDADIS-IV and psychiatrists’ diagnoses agreed well (K=0.64–0.68, sensitivity=.76, and specificity=.93) (24).

Predictors of Outcomes

Predictor variables tested included 1) demographic characteristics, 2) other DSM-IV Axis I disorders, 3) personality disorders, 4) clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder course, 5) family history, and 6) treatment history.

Demographic characteristics

These included gender, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and education.

Other Axis I Disorders

AUDADIS-IV operationalizes DSM-IV disorders for alcohol, ten drug classes, and nicotine (25, 26), with good to excellent inter-rater and test-retest reliability (e.g., K=0.70–0.84) and validity (24). Dysthymic disorder and anxiety disorders including panic, social anxiety, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorders were assessed. Test-retest reliability was adequate for dysthymic disorder and anxiety disorders (K=0.40–0.69) (24) and validity was indicated by significant associations with impairment on the Short Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12version2) (27).

Personality disorders

All 10 DSM-IV personality disorders were assessed by algorithms requiring the specified numbers of diagnostic criteria, as well as evidence of long-term maladaptive patterns of cognition, emotion, and functioning (28–32). Personality disorders, except for antisocial, were assessed with an introduction and repeated reminders asking respondents to answer about how they felt or acted “most of the time, throughout your life, regardless of the situation or whom you were with.” Respondents were instructed not to include symptoms occurring only when depressed, manic, anxious, drinking heavily, using drugs, recovering from the effects of alcohol or drugs, or physically ill. Personality disorder criteria items were adapted from items in the DSM-IV versions of semi-structured diagnostic interviews (e.g., the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders and Personality Disorder Examination) that have longstanding histories of being reliably used in research studies of patient groups (33). For all symptoms coded positive, respondents were asked “Did this ever trouble you or cause problems at work or school, or with your family or other people?” Scoring algorithms for diagnoses required endorsement of associated distress or social/occupational dysfunction, in addition to the number of specified criteria (32).

Avoidant, dependent, histrionic, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, and schizoid personality disorders were assessed at Wave 1; borderline, narcissistic, and schizotypal were assessed at Wave 2. Lifetime antisocial personality disorder was assessed at Wave 1, with adult symptoms re-assessed at Wave 2. Antisocial personality disorder was considered present if respondents met criteria for lifetime disorder at Wave 1 and at least three adult criteria persisted at Wave 2. Test-retest studies in the NESARC indicate reliability ranging from fair (paranoid, histrionic, avoidant, K=0.40–0.45) to very good (schizotypal, antisocial, narcissistic, borderline, K=0.67–0.71) (23, 34), generally comparable to the range reported for patient studies (33, 35). Associations with impairment indicate good convergent validity for these diagnoses (26, 28–32).

Because not all personality disorders were measured at Wave 1, we investigated their validity at both waves among the 1,996 respondents, using two methods. The first method, using weighted linear regressions, compared respondents with each personality disorder to those without on impairment at Waves 1 and 2, measured with the Mental Component Summary of the SF-12v2 (27). Some between-wave change in scores occurred, as expected (36), but the participants with personality disorders consistently had greater (p<.0001) impairment in both Waves and 2, regardless of the wave in which the disorder was assessed (Online Table 1). The second method, using logistic regression, compared respondents with each personality disorder to those without on Wave 1 and 2 life events suggesting impaired functioning, such as breaking up of relationships; problems with friends, employer, or finances; being fired or laid off; and being unemployed and looking for work. As summarized in Online Table 2, respondents with personality disorders were more likely to experience the events at both Waves 1 and 2, regardless of when their disorder was diagnosed. The consistency of association of both impairment indicators with personality disorders at Waves 1 and 2, regardless of when the disorder was assessed, further supported the validity of the diagnoses.

Table 1.

Population Attributable Risk Proportions for Effects of Co-occurring Psychopathology and Related Factors on Persistence of Major Depressive Disorder Over Three Years

| Predictor Variable | Percent with MDDa at Follow-up | Percent without MDD at Follow-up | Population Attributable Risk Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personality Disorders | |||

| Antisocial | 20.29 | 15.29 | 24.64 |

| Avoidant | 23.12 | 14.50 | 37.28 |

| Borderline | 28.90 | 12.33 | 57.34 |

| Dependent | 22.42 | 15.20 | 32.20 |

| Histrionic | 24.18 | 14.90 | 38.38 |

| Narcissistic | 14.60 | 15.41 | −5.55 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 19.33 | 14.42 | 25.40 |

| Paranoid | 21.78 | 14.19 | 34.85 |

| Schizoid | 26.93 | 14.02 | 47.94 |

| Schizotypal | 26.07 | 14.26 | 45.30 |

| Axis I Disorders | |||

| Dysthymic disorder | 22.79 | 14.01 | 38.53 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 22.21 | 12.58 | 43.36 |

| Any substance use disorder | 15.33 | 15.32 | 00.07 |

| Other Predictors | |||

| Family history depression | 15.93 | 14.41 | 09.54 |

| Family history substance use or antisocial personality | 15.79 | 14.72 | 06.78 |

| Depression treatment Wave 1 | 23.75 | 12.52 | 47.28 |

| Onset of MDD < age 15 | 17.57 | 14.72 | 16.22 |

MDD = major depressive disorder

Table 2.

Predictors of Major Depressive Disorder Persistence (N=302) among those who had Major Depressive Disorder at W1 (N=1,996): Odds ratios (95% Confidence Intervals)

| Personality Disorder | Control variables | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

| Demographic characteristicsa | Model 1 variables + Axis I disordersb | Demographics, all Axis I disordersb + all personality disorders | Model 3 variables + family historyc | Model 4 variables + other persistence predictors d | ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Antisocial | 1.98 | 0.70–5.58 | 1.58 | 0.56–4.46 | 0.84 | 0.29–2.39 | 0.83 | 0.29–2.37 | 0.92 | 0.28–3.03 |

| Avoidant | 1.97** | 1.25–3.10 | 1.72* | 1.07–2.75 | 1.28 | 0.74–2.21 | 1.28 | 0.74–2.22 | 1.24 | 0.62–2.51 |

| Borderline | 3.24** | 2.34–4.49 | 3.12** | 2.24–4.34 | 3.12** | 2.17–4.49 | 3.12** | 2.17–4.50 | 2.51** | 1.67–3.77 |

| Dependent | 1.67 | 0.58–4.82 | 1.32 | 0.42–4.13 | 0.55 | 0.17–1.86 | 0.56 | 0.17–1.87 | 0.39 | 0.11–1.41 |

| Histrionic | 2.20* | 1.14–4.24 | 1.86 | 0.93–3.69 | 1.68 | 0.85–3.30 | 1.68 | 0.85–3.29 | 1.64 | 0.81–3.30 |

| Narcissistic | 1.09 | 0.69–1.72 | 1.06 | 0.67–1.68 | 0.49 | 0.28–0.86 | 0.49 | 0.28–0.86 | 0.54 | 0.28–1.03 |

| OCPD | 1.40 | 0.94–2.08 | 1.26 | 0.85–1.88 | 1.02 | 0.66–1.58 | 1.03 | 0.66–1.56 | 0.96 | 0.58–1.58 |

| Paranoid | 1.80** | 1.21–2.68 | 1.58* | 1.03–2.42 | 0.98 | 0.60–1.60 | 0.99 | 0.61–1.60 | 1.11 | 0.67–1.87 |

| Schizoid | 2.46** | 1.54–3.95 | 2.30** | 1.44–3.65 | 1.72* | 1.04–2.85 | 1.72* | 1.04–2.86 | 1.63 | 0.95–2.80 |

| Schizotypal | 2.23** | 1.37–3.65 | 2.07** | 1.28–3.36 | 1.22 | 0.65–2.29 | 1.22 | 0.65–2.29 | 1.36 | 0.65–2.85 |

controlled for age, sex, education, marital status, and race/ethnicity

dysthymic disorder, any anxiety disorder, and any substance use disorder

family history of depression, alcohol, drug and antisocial personality disorders

current treatment, age at major depressive disorder onset, number of episodes, and duration of most recent episode

p<0.05

p<0.01

Clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder course

Since early onset, recurrence, and previous chronicity predicted persistent major depressive disorder in some studies (7, 8, 12, 13), analyses included age at first onset (<15, 15–17, ≥18), number of prior episodes, and duration of current episode.

Family history

Family history of depression, antisocial personality disorder, and alcohol or drug use disorders were also investigated as predictors. Family history was assessed by reading observable manifestations of each disorder to respondents, and asking about disorders among relatives, including parents and siblings; test-retest reliability was good to excellent (25).

Treatment

Treatment for major depressive disorder was examined, including outpatient services (counselor, therapist, physician, or other professional), inpatient services (hospitalized overnight or longer), and prescribed medication (37).

Statistical Analyses

Weighted means, frequencies and unvariate associations were computed. Relationships between predictors and the two binary outcome variables (persistent and recurrent MDD), were tested with multiple logistic regression models, producing adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Standard errors and 95% CIs for the predictors were estimated with SUDAAN, which uses Taylor series linearization to adjust for design effects of complex sample surveys.

We first tested the individual effects of Axis I disorders, adjusting for demographics. We then tested a model including the demographics and all other Axis I disorders, controlling for co-morbidity to indicate any potential unique effect of each disorder. Bipolar I and II disorders were excluded from analyses.

We calculated population attributable risk proportions for an additive measure of the effect of our predictors on major depressive disorder persistence. This fraction is calculated by subtracting the proportion of persistence in those with the predictor from the proportion of persistence among those without the predictor, and dividing by the proportion of persistence with the predictor. The resulting attributable risk indicates the proportion of the outcome that would not occur in the absence of the predictor.

To examine the impact of personality disorders on major depressive disorder persistence, we first tested individual models for each personality disorder, controlling for demographics. We then added the Axis I disorders to these models to determine whether apparent personality disorder effects arose from Axis I co-morbidity. We then tested a model that included demographics, Axis I disorders, and all 10 personality disorders simultaneously. Given the considerable co-morbidity of personality disorders with each other (38), this model was intended to control for the effects of all other personality disorders when examining each one, to determine if any specific one had unique effects. We then tested a model to indicate the robustness of unique personality disorder effects by adding family history. Finally, to further test the robustness of personality disorders as predictors, we tested a model with all of the demographic variables, Axis I and personality disorders, and family history, plus age at onset, number of lifetime episodes, most recent episode duration, and current treatment for major depressive disorder.

Results

Of the 1,996 respondents diagnosed with major depressive disorder at Wave 1, 302 (15.1%) (SE=1.0) had persistent disorder at Wave 2, meeting full criteria for major depressive disorder throughout the entire three-year follow-up, without mania or hypomania. One hundred and forty-five (145) of the 1,996 (7.3%) (SE=0.7) who had major depressive disorder at Wave 1 and remitted had a subsequent recurrence.

Of the demographic variables, only gender predicted major depressive disorder persistence or recurrence. Males were less likely than females to have an episode persist (odds ratio=0.66, 95% CI=0.45–0.97) or recur (odds ratio= 0.55, 95% CI=0.33–0.91) by Wave 2. Among Axis I disorders, dysthymic disorder (odds ratio=1.79, 95% CI=1.23–2.60), any anxiety disorder (odds ratio=1.96, 95% CI=1.43–2.68), specific phobia (odds ratio=2.19, 95% CI=1.53–3.12), and panic disorder (odds ratio=2.18, 95% CI=1.30–3.68) all predicted persistence. After additionally controlling for other Axis I disorders, dysthymic disorder (odds ratio=1.75, 95% CI=1.20–2.54), specific phobia (odds ratio=2.08, 95% CI=1.46–2.99), and panic disorder (odds ratio=1.87, 95% CI=1.11–3.15) remained significant predictors of persistence. No co-morbid Axis I disorder predicted recurrence.

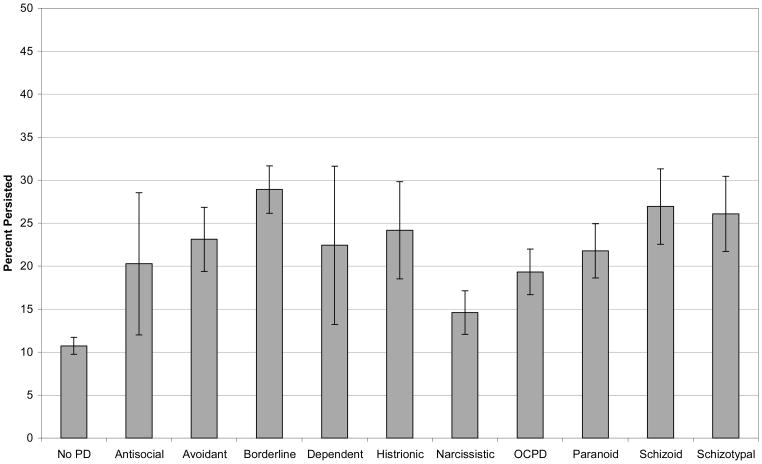

Figure 1 shows the percent of participants who had persistent major depressive disorder by each of the 10 personality disorders and no personality disorder. Among participants with a personality disorder, those with borderline had the highest percent of persistence (28.9%, SE=2.75) and those with narcissistic had the lowest (14.6%, SE=2.52). Several personality disorders predicted major depressive disorder persistence in univariate analyses, including avoidant (odds ratio=1.97, 95% CI=1.25–3.10), borderline (odds ratio=3.23, 95% CI=2.34–4.49), histrionic (odds ratio=2.20, 95% CI=1.14–4.24), paranoid (odds ratio=1.80, 95% CI=1.21–2.68), schizoid (odds ratio=2.46, 95% CI=1.54–3.95), and schizotypal (odds ratio=2.23, 95% CI=1.37–3.65) personality disorders. No personality disorder predicted recurrence.

Figure 1.

Percent of MDD Persistence by Personality Disorder Status, among those who had MDD at W1 (N=1,996)

No family history variable predicted persistence, but a family history of depression predicted recurrence (odds ratio=1.72, 95% CI=1.11–2.67). History of treatment for major depressive disorder predicted persistence (odds ratio=2.07, 95% CI=1.48–2.89), but not recurrence. Among other clinical features of major depressive disorder, earlier age at onset (odds ratio= 0.97, 95% CI=0.96–0.99) and number of previous episodes (odds ratio=1.02, 95% CI=1.01–1.03) weakly predicted persistence, while duration of most recent episode did not. No clinical feature significantly predicted recurrence.

Table 1 presents the population attributable risk proportions for the effects of co-occurring psychopathology and related risk factors on the persistence of major depressive disorder. Those disorders with the highest values included borderline (57.3%), schizoid (47.9%), and schizotypal (45.3%) personality disorders; and any anxiety disorder (43.4%).

Table 2 displays the results of the multivariate analyses testing the associations of personality disorders with major depressive disorder persistence. In Model 1, with demographic factors controlled, avoidant, borderline, histrionic, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders all remained significant predictors. In Model 2, with additional controls for Axis I disorder co-morbidity, avoidant, borderline, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders remained significant. In Model 3, with all personality disorders added simultaneously to the model, only borderline and schizoid remain significant. The addition of family history of psychiatric and substance use disorders (Model 4) resulted in virtually no change in the results. When a history of treatment, age at first onset, number of previous episodes, and duration of current episode at Wave 1 were added (Model 5), borderline personality disorder remained a robust predictor of major depressive disorder persistence (odds ratio=2.51, 95% CI=1.67–3.77).

Discussion

This study provides a rigorous test of the impact of personality disorders on the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally-representative sample assessed with a well-established instrument. A large number of participants were ascertained independently of treatment status and re-evaluated three years later with excellent retention to determine the rates of persistence and recurrence of major depressive disorder. This study tested the prognostic significance of personality disorders while controlling for demographic factors, psychiatric and other personality disorder co-morbidity, clinical factors that could have impacted the course of major depressive disorder, family history, and treatment history. The large sample allowed for multivariate tests of predictors in a logical progression that enabled the untangling of the effects of these multiple factors in a manner not possible in previous smaller studies.

In this study, co-morbid personality disorders, anxiety disorders, and dysthymic disorder significantly predicted persistence of major depressive disorder. According to population attributable risk proportions, borderline personality disorder was the strongest predictor, followed by schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders, any anxiety disorder (the strongest Axis I disorder predictor), and dysthymic disorder. Population attributable risk proportions indicate the proportion of persistence of major depressive disorder attributable to each disorder. Thus, approximately 57% of cases would not have persisted to follow-up in the absence of borderline personality disorder, a larger proportion than any Axis I disorder. Even after controlling for other potentially negative prognostic indicators, borderline personality disorder significantly and robustly predicted major depressive disorder persistence.

Overall, the 84.9% remission rate of major depressive disorder in this 3-year follow-up study is comparable to rates observed in two major NIMH-funded prospective studies of patient groups. The NIMH-Collaborative Depression Study (CDS) reported major depressive disorder remission rates of 70% at 2 years and 88% at 5 years (14), while the CLPS reported remission rates of 73.5% at 2 years (24) and 86% at 6 years (25). Our findings that personality disorders are negative prognostic indicators for the course of major depressive disorder and that borderline personality disorder, in particular, is a robust independent predictor of chronicity are consistent with the findings from the CLPS (17, 18) and from an earlier Norwegian study using DSM-III criteria (39). Grilo and colleagues (17) reported that the co-occurrence of personality disorders in patients with major depressive disorder predicted significantly longer time to remission even when controlling for several other negative prognostic factors. Our findings, which controlled more comprehensively for co-morbidity of Axis I and Axis II disorders, and clinical, family, and treatment variables, highlights the specific negative effects of borderline personality disorder on major depressive disorder persistence.

Overall, the 7.3% recurrence rate among remitted participants is substantially lower than the relapse rates observed in the CDS over five years (11) and the CLPS over six years (18). In contrast to the CLPS (18), which found that borderline personality disorder predicted shorter time to relapse, the present study found no significant predictors of recurrence except for gender and family history of depression. This discrepancy may reflect, in part, the intensive weekly tracking of the symptoms of major depressive disorder in the CLPS compared to the one-time re-test in the present study. Alternatively, the discrepancy may reflect differences in major depressive disorder severity between general population and clinical samples (19).

Our findings should be interpreted considering the study’s strengths and potential limitations. Strengths include: epidemiological sampling to obtain a large nationally-representative study of adults with major depressive disorder ascertained independently of treatment-seeking; use of reliable and standardized measures; high retention rates over three-year follow-along; consideration of both persistence and recurrence as outcomes; and multivariate analyses controlling for a comprehensive set of potential predictors. Potential limitations include: reliance on data obtained with structured interviews administered by trained lay interviewers rather than trained clinicians; reliance on only one follow-up time point three years later (i.e., additional waves over a longer follow-up period may have allowed more observations of recurrences); focus on DSM-IV categorical personality disorder diagnoses (i.e., alternative dimensional models were not tested); and three personality disorders assessed at Wave 2. While our impairment analyses supported the validity of the personality disorder diagnoses regardless of the timing of their assessment, the design introduced the small possibility that the timing of the assessments might have affected the results.

In summary, our findings confirm the growing clinical literature on the negative prognostic effects of personality disorders on the course of major depressive disorder and extend these findings to a nationally-representative sample of adults unselected for treatment-seeking. Our primary finding was that borderline personality disorder significantly and robustly predicted persistence even after controlling for other potentially negative prognostic indicators. The findings suggest the need to assess personality disorders in depressed patients for consideration in both prognosis and treatment (40).

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants U01AA018111 from the NIAAA and K05 AA014223 from NIMH (Dr. Hasin) and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Footnotes

The authors have no interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Chui W, Demler O, Merikangas K, Walters E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic análysis of population heath data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, Warshaw M, Maser JD. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1000–1006. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Shea MT, Warshaw M, Maser JD, Coryell W, Endicott J. Recovery from major depression: a 10-year prospective follow-up across multiple episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1001–1006. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Amsterdam JD, Salomon RM, O’Reardon JP, Lovett ML, Young PR, Harman KL, Freeman BB, Gallop R. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medication in moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:417–422. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bockting CL, Spinhoven P, Koeter MW, Wouters LF, Schene QA. Prediction of recurrent depression and the influence of consecutive episodes on vulnerability for depression: a 2-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:747–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Lewis CE, Klerman GL. Predictors of relapse in major depressive disorder. JAMA. 1983;250:3299–3304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller MB, Shapiro RW, Lavori PW, Wolfe N. Recovery in major depressive disorder: analysis with the life table and regression models. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:905–910. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein DN, Shankman SA, Rose S. Ten-year prospective follow-up study of the naturalistic course of dysthymic disorder and double depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:872–880. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Coryell W, Hirschfeld RMA, Shea MT. Time to recovery, chronicity and levels of psychopathology in major depression: a 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:809–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100053010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein DN, Schatzberg AF, McCullough JP, Dowling F, Goodman D, Howland RH, Markowitz JC, Smith C, Thase ME, Rush AJ, Lavange L, Harrison WM, Keller MB. Age of onset in chronic major depression: relationship to demographic and clinical variables, family history, and treatment response. J Affective Disord. 1999;55:149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Yonkers KA, McCullough JP, Keitner GI, Gelenberg AJ, Ryan CE, Hess AL, Harrison W, Davis SM, Keller MB. Gender differences in chronic major and double depression. J Affective Disord. 2000;60:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Skodol AE. Stability and course of personality disorders: the need to consider comorbidities and continuities between axis I psychiatric disorders and axis II personality disorders. Psychiatr Quart. 2000;71:291–309. doi: 10.1023/a:1004680122613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulder RT. Personality pathology and treatment outcome in major depression: a review. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:359–371. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, Grilo CM, Oldham JM, Keller MB. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. J Personal Disord. 2000;14:300–315. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Gunderson JG, Yen S, Bender DS, Pagano ME, Zanarini MC, Morey LC, McGlashan TH. Two-year prospective naturalistic study of remission from major depressive disorder as a function of personality disorder comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:78–85. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grilo CM, Stout RL, Markowitz JC, Sanislow CA, Ansell EB, Skodol AE, Bender DS, Pinto A, Shea MT, Yen S, Gunderson JG, Morey LC, McGlahan TH. Personality disorders predict relapse after remission from an episode of major depressive disorder: a six-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04200gre. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen P, Cohen J. The clinician’ illusion. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:1178–1182. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790230064010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Prevalence and co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Saha TD, Smith SM, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—DSM-IV version (AUDADIS-IV) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canino GJ, Bravo M, Ramfrez R, Febo V, Fernandez R, Hasin D. The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability and concordance with clinical diagnosis in a Hispanic population. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:790–799. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heiman GA, Ogburn E, Gorroochurn P, Keyes KM, Hasin D. Evidence for a two-stage model of dependence using the NESARC and its implications for genetic association studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Colliver JD, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:677–685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JE, Kosinkski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Smith SM, Ruan WJ, Pulay AJ, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV narcissistic personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1033–1045. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou PS, Huang B, Smith SM, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP, Hasin DS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/pcc.08m00679. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Ruan WJ, Huang B. Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:948–958. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Kellman HD, Hyler SE, Rosnick L, Davies M. Diagnosis of DSM-III-R personality disorders by two structured interviews: patterns of comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:213–220. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Dawson DA, Huang B, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimmerman M. Diagnosing personality disorders. a review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:225–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030061006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skodol AE. Longitudinal course and outcome of personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keyes K, Hatzenbuehler M, Alberti P, Narrow W, Grant B, Hasin D. Service utilization for axis I psychiatric and substance disorders in white and black adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:893–901. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.8.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ. Co-occurrence of DSM-IV personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alnaes R, Torgersen S. Personality and personality disorders predict development and relapses of major depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95:336–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Gallop R, Amsterdam JD, Hollon SD. Antidepressant medication v. cognitive therapy in people with depression with or without personality disorder. Brit J Psychiatry. 2008;192:124–129. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]