Abstract

The L232A mutation at triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) from Trypanosoma brucei brucei results in a small 6-fold decrease in kcat/Km for the reversible enzyme-catalyzed isomerization of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to give dihydroxyacetone phosphate. By contrast, this mutation leads to a 17-fold increase in the second-order rate constant for the TIM-catalyzed proton transfer reaction of the truncated substrate piece [1-13C]-glycolaldehyde ([1-13C]-GA) in D2O; a 25-fold increase in the third-order rate constant for reaction of the substrate pieces GA + and phosphite dianion (HPO32-); and a 16-fold decrease in Kd for binding of HPO32- to the free enzyme. Most significantly, the mutation also results in an 11-fold decrease in the extent of activation of the enzyme towards turnover of GA by bound HPO32-. The data provide striking evidence that the L232A mutation leads to a ca. 1.7 kcal/mol stabilization of a catalytically active loop-closed form of TIM (Ec) relative to an inactive open form (Eo). We propose that this is due to the relief, at L232A mutant TIM, of unfavorable steric interactions between the bulky hydrophobic side chain of Leu-232 and the basic carboxylate side chain of Glu-167, the catalytic base, which destabilize Ec relative to Eo.

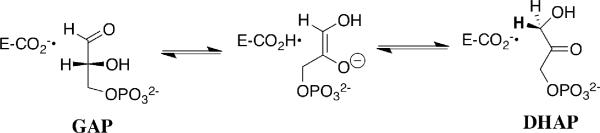

Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) catalyzes the stereospecific and reversible 1,2-hydrogen shift at dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) to give (R)-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) by a single base (Glu-167)1 proton transfer mechanism through an enzyme-bound cis-enediolate reaction intermediate (Scheme 1).2-4 TIM catalyzes proton transfer at carbon in an early step in glycolysis, a remarkably successful metabolic pathway.5,6 The enzyme appeared early during the evolution of life, and is potentially an ancestor of other enzymes that catalyze deprotonation of carbon, or that contain the eponymous TIM barrel. Conclusions about the mechanism of action of TIM might therefore be generalized to many other enzymatic reactions.

Scheme 1.

The identity and location of the catalytic amino acid side chains at TIM define the elementary chemical steps for enzyme-catalyzed isomerization.7,8 By contrast, there is no consensus of opinion about the origin of the large catalytic rate acceleration. We have shown that TIM uses binding interactions with the nonreacting phosphodianion group of the substrate to stabilize the transition state for enzyme-catalyzed isomerization of GAP by 12 kcal/mol, which represents ca. 80% of the total enzymatic rate acceleration.9 The binding interactions with the phosphodianion group anchor the substrates GAP and DHAP to TIM and activate the enzyme for catalysis of carbon deprotonation.10 Around 50% of this intrinsic phosphate binding energy is observed as specific stabilization of the transition state by the binding of phosphite dianion to the transition state for the TIM-catalyzed reaction of the truncated substrate glycolaldehyde (GA) in a two-part substrate experiment, where the covalent connection between the carbon acid and phosphodianion parts of the substrate has been eliminated.10,11

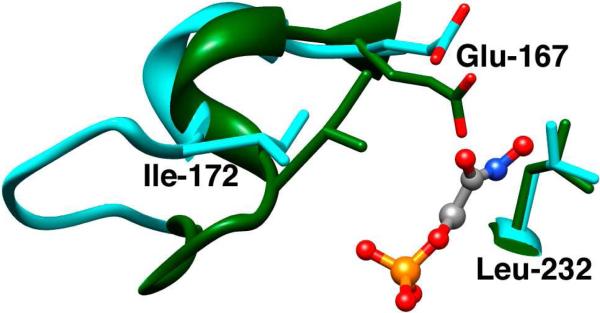

Flexible loop 6 of the TIM barrel fold is disordered at unliganded TIM but is folded over the phosphodianion group of enzyme-bound DHAP12,13 and the inhibitors 2-phosphoglycolate (PGA)14 and 2-phosphoglycolohydroxamate (PGH).15 This closure of loop 6 over the substrate or inhibitor (Figure 1) is the most dramatic of the many changes in the protein conformation that occur upon formation of complexes between TIM and phosphodianion ligands.4 We have proposed that these ligand-induced conformational changes activate TIM for catalysis of deprotonation of carbon.10,11,16,17

Figure 1.

Models, from X-ray crystal structures, of the unliganded open (cyan, PDB entry 5TIM) and the PGH-liganded closed (green, PDB entry 1TRD) forms of TIM from Trypanosoma brucei brucei in the region of the enzyme active site. Closure of loop 6 (residues 168 – 178) over the ligand phosphodianion group results in movement of the hydrophobic side chain of Ile-172 towards the carboxylate side chain of the catalytic base Glu-167. This is accompanied by movement of Glu-167 towards the hydrophobic side chain of Leu-232, which maintains a nearly fixed position.

Wierenga and coworkers made the astute observation that the closure of loop 6 of TIM over the bound ligand PGA results in movement of the hydrophobic side chain of Ile-172 toward the carboxylate side chain of the catalytic base Glu-167 and “drives” this anionic side chain toward the hydrophobic side chain of Leu-232, which maintains a nearly fixed position (see Figure 1).18 This conformational change sandwiches the catalytic base at the loop-closed enzyme between two hydrophobic side chains (Figure 1) and shields it from interactions with bulk solvent. This hydrophobic local environment should lead to an increase in the basicity of the carboxylate side chain of Glu-167 and hence in its reactivity toward deprotonation of carbon, relative to its reactivity in aqueous solution.

If Leu-232 plays a significant role in activating TIM for catalysis of deprotonation of carbon, then the L232A mutation should result in significant changes in the kinetic parameters for TIM-catalyzed reactions. We prepared the L232A mutant of TIM from Trypanosoma brucei brucei (Tbb TIM) starting from a plasmid containing the gene for wildtype Tbb TIM,17,19 using the standard protocol described in the Supporting Information. Table 1 gives the kinetic parameters for the isomerization reactions of GAP and DHAP catalyzed by wildtype17 and L232A mutant Tbb TIM at pH 7.5, 25 °C and I = 0.1. These data show that the L232A mutation leads to only a small 6-fold falloff in kcat/Km for the enzyme-catalyzed reactions of GAP and DHAP. The mutation results in a small decrease in Km for isomerization of GAP, but a surprisingly large 9-fold decrease in Km for the reaction of DHAP, and a compensating 60-fold decrease in kcat for its isomerization to give GAP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kinetic Parameters for the reactions of GAP, DHAP, and [1-13C]-GA catalyzed by wildtype and L232A mutant triosephosphate isomerase from Trypanosoma brucei brucei.

| GAPa | DHAPa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tbb TIM | kcat (s-1) | Km (M) | kcat/Km (M-1 s-1) | kcat (s-1) | Km (M) | kcat/Km (M-1 s-1) |

| Wildtypeb | 2100 | 2.5 × 10-4 | 8.4 × 106 (1.7 × 108)c | 300 | 7.0 × 10-4 | 4.3 × 105 (7.2 × 105)c |

| L232A | 220 | 1.4 × 10-4 | 1.5 × 106 (3.0 × 107)c | 4.7 | 7.7 × 10-5 | 6.1 × 104 (1.0 × 105)c |

| [1-13C]-GAd | {[1-13C]-GA + HPO32-}d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kcat/Km)E (M-1 s-1) | Kd (M) | (kcat/Km)E•HPi (M-1 s-1) | (kcat/Km)E•HPi/Kd (M-2 s-1) | Phosphite Activation (kcat/Km)E•HPi/(kcat/Km)E | |

| Wildtypeb,e | 0.07 | 0.019 | 64 | 3400 | 900-fold |

| L232Ae | 1.2f | 1.2 × 10-3g | 100g | 8.3 × 104 | 80-fold |

At pH 7.5 (30 mM triethanolamine), 25 °C and I = 0.1 (NaCl), determined as described previously.17 The range of error in the reported values of kcat and Km is estimated to be ± 10%.

Data from Ref. 17.

The values in parentheses have been corrected for the fraction of GAP (5%) or DHAP (60%) present in the reactive free carbonyl form.

In D2O at pD 7.0 (10 - 20 mM imidazole), 25 °C and I = 0.1 (NaCl). The range of error in the reported values of kcat/Km and Kd is estimated to be ± 10%.

The reported parameters refer to the reactive free carbonyl form of [1-13C]-GA.

Average of two determinations in the absence of phosphite dianion.

The disappearance of [1-13C]-GA catalyzed by L232A mutant Tbb TIM in D2O to give the products of proton transfer (a mixture of [2-13C]-GA, [2-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA) at pD 7.0, 25 °C and I = 0.1 in the absence and presence of phosphite dianion was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy, as described previously for the wildtype enzyme.17 First-order rate constants, kobs (s-1), were determined from the slopes of linear semi-logarithmic plots of reaction progress against time covering 70 - 80 % of the reaction according to eq 1, where fS is the fraction of [1-13C]-GA that remains at time t. The observed second-order rate constants for these TIM-catalyzed proton transfer reactions of [1-13C]-GA in D2O, (kcat/Km)obs (M-1 s-1), were determined from the values of kobs using eq 2, where fhyd = 0.94 is the fraction of [1-13C]-GA present as the hydrate form and [E] is the concentration of TIM.10,11 We also determined the yields of the products of the L232A Tbb TIM-catalyzed reactions of GAP20 and [1-13C]-GA10,11,17 in D2O and these data will be reported in a later publication.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

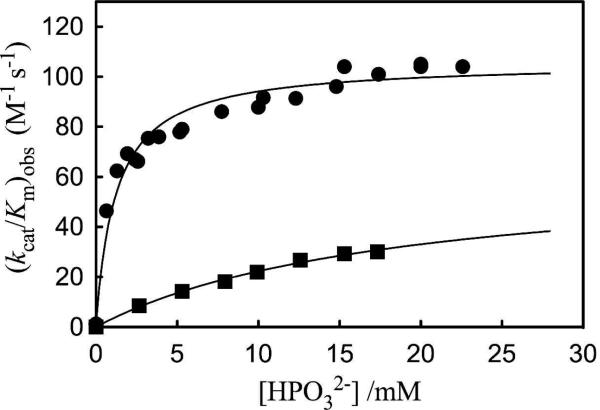

Figure 2 shows the effect of increasing concentrations of phosphite dianion on (kcat/Km)obs for the deprotonation of [1-13C]-GA catalyzed by wildtype Tbb TIM17 and by the L232A mutant enzyme. These data were fit to eq 3, derived for Scheme 2, with the values of (kcat/Km)E for the unactivated reaction in the absence of phosphite (Table 1), to give the values of Kd and (kcat/Km)E•HPi reported in Table 1. We note the following effects of the L232A mutation on these kinetic parameters: (1) A 17-fold increase in the second-order rate constant (kcat/Km)E for the unactivated reaction of GA from 0.07 to 1.2 M-1 s-1. (2) A 24-fold increase in the third-order rate constant (kcat/Km)E•HPi/Kd for reaction of the substrate pieces {GA + HPO32-}. (3) A 16-fold decrease in the dissociation constant Kd for the phosphite dianion activator, from 19 mM to 1.2 mM. (4) Only a small change in the second-order rate constant (kcat/Km)E•HPi for reaction of the substrate piece GA catalyzed by the TIM•HPO32- complex, from 64 M-1 s-1 to 100 M-1 s-1. (5) An 11-fold decrease, from 900-fold to 80-fold, in the extent of activation of Tbb TIM towards deprotonation of GA upon the binding of phosphite to give the E•HPO32- complex, calculated as the ratio (kcat/Km)E•HPi/(kcat/Km)E (Scheme 2). In summary, to our surprise, the L232A mutation leads to only a relatively small decrease in kcat/Km for the physiological isomerization reactions of GAP and DHAP, but to an increase in the reactivity of the enzyme towards the substrate pieces GA and phosphite dianion in a two-part substrate experiment.

Figure 2.

The dependence of the observed second-order rate constant (kcat/Km)obs for the proton transfer reactions of the free carbonyl form of [1-13C]-GA (20 mM total substrate) catalyzed by wildtype and L232A mutant Tbb TIM on the concentration of phosphite dianion in D2O at pD 7.0 (10 - 20 mM imidazole), 25 °C and I = 0.1 (NaCl). Key: (■) Data for wildtype Tbb TIM (Ref. 17); (●) Data for L232A mutant Tbb TIM.

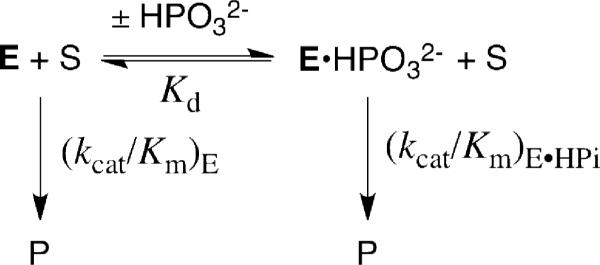

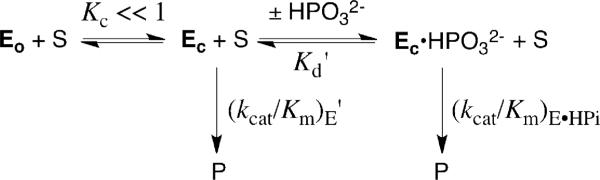

Scheme 2.

The observation that the mutation of a highly conserved residue results in an increase in the efficiency of the TIM-catalyzed reaction of the substrate pieces (increases in (kcat/Km)E and (kcat/Km)E•HPi/Kd) provides strong evidence that the deleted hydrophobic side chain of Leu-232 plays an important role in the activation of TIM for deprotonation of carbon. They are consistent with the proposal that the L232A mutation leads to an increase in the equilibrium constant Kc for the thermodynamically unfavorable conversion of an inactive loop open form of TIM (Eo) to a higher energy, but active, loop closed enzyme (Ec) that shows a high specificity for the binding of phosphite dianion and the transition state for deprotonation of GA (Scheme 3).10,11,16 In this model the closed enzyme Ec is assumed to have a reactivity toward carbon deprotonation that is essentially identical to that of the phosphite-liganded closed enzyme species Ec•HPO32-, so that (kcat/Km)E' = (kcat/Km)E•HPi (Scheme 3).10,11,16 The value of Kc can then be obtained from the ratio of the second-order rate constants for turnover of the substrate piece GA by the phosphite-liganded enzyme and the free enzyme according to eq 5, which is the magnitude of activation of the enzyme by the binding of phosphite dianion (Table 1). The increase in Kc due to the L232A mutation is estimated to be ca. 17-fold, calculated as the average of the effects of the mutation on the kinetic parameters (kcat/Km)E (17-fold), Kd (16-fold), (kcat/Km)E•HPi/Kd (24-fold) and the observed 11-fold decrease in the extent of enzyme activation by bound phosphite (Table 1).

| (5) |

Scheme 3.

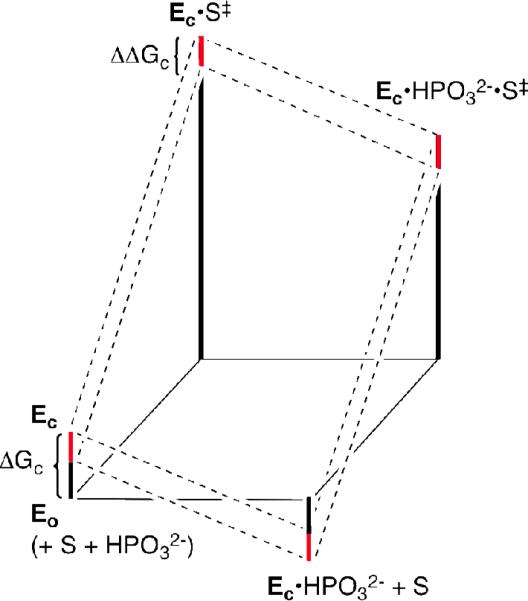

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of a decrease in ΔGc (increase in Kc) and hence an increase in the fraction of enzyme present in the active closed form (Ec, Scheme 3) on the kinetic parameters for reaction of the substrate pieces {GA + HPO32-}. The overall barrier to the change from Eo to Ec (ΔGc = 4.0 kcal/mol) for wildtype Tbb TIM is given by the SUM of the red and black bars in the lower left hand corner of Figure 3. The red bars show the magnitude of the effect of the L232A mutation on this barrier, ΔΔGc ≈ 1.7 kcal/mol. The decrease in ΔGc for L232A mutant TIM is expected to lead to the following changes in the kinetic parameters that depend on the fraction of enzyme present as Ec (Figure 3): (1) An increase in the second-order rate constant for turnover of the substrate piece GA, (kcat/Km)E, as a result of stabilization of the transition state Ec•S‡ relative to the ground state Eo + S. (2) A decrease in the dissociation constant for the phosphite dianion activator (Kd), due to the stabilization of Ec•HPO32-. (3) An increase in the third-order rate constant (kcat/Km)E•HPi/Kd for turnover of the two-part substrate {GA + HPO32-} as a result of stabilization of Ec•HPO32-•S‡. On the other hand, the magnitude of the activation of TIM for deprotonation of GA by the binding of phosphite dianion should decrease with increasing Kc, until only a minimal two-fold activation is observed for Kc = 1 (eq 5). The observed 11-fold decrease in phosphite activation of the L232A mutant enzyme-catalyzed reaction of GA from 900-fold to 80-fold (Table 1) is therefore consistent with an increase in Kc (decrease in ΔGc, Figure 3). We suggest that the effect of the L232A mutation on ΔΔGc (Figure 3) results from the relief of a ca. 1.7 kcal/mol destabilizing steric interaction between the hydrophobic side chain of Leu-232 and the carboxylate anion of Glu-167, the catalytic base. We propose that this strain is induced by loop closure that moves the carboxylate side chain from a catalytically inactive swung-out position to the reactive swung-in conformation (Figure 1).4,18

Figure 3.

Proposed free energy profiles for the turnover of glycolaldehyde (S) by free TIM (Eo) and by the phosphite-liganded enzyme Ec•HPO32-. The red bars show the effect of the L232A mutation on the barrier for the conformational change from Eo to Ec (ΔΔGc). The effect of this change in ΔGc on turnover of the substrate pieces is shown by a comparison of the reaction profiles for wildtype TIM (upper dashed lines) and L232A mutant TIM (lower dashed lines).

The small ca. six-fold decreases in kcat/Km for the TIM-catalyzed isomerization of the whole substrates GAP or DHAP as a result of the L232A mutation (Table 1) cannot be rationalized simply by an increase in the concentration of active Ec relative to inactive Eo. We note that this mutation results in even larger ca. 150-fold decreases in the ratio of kcat/Km for isomerization of the whole substrate GAP or DHAP and (kcat/Km)E•HPi/Kd for reaction of the two-part substrate {GA + HPO32-}. Effective catalysis of the reaction of the whole substrate or of the pieces {GA + HPO32-} requires the development of optimal binding interactions between TIM and the carbon acid and dianion portions of the substrate or the pieces. We suggest that the L232A mutation leads to a small shift in the position of the active site catalytic residues that leads to a specific decrease in the stabilization of the transition state for the reaction of the whole substrate GAP or DHAP, but not for the reaction of {GA + HPO32-}, because these pieces are able to move independently at the active site.

The proposal that unliganded TIM exists mainly in the catalytically inactive open form Eo might appear to make TIM less perfect than an enzyme that exists exclusively in the active form, because the second-order rate constant for the reaction of poor substrates such as GA with the ground state Eo will decrease in direct proportion to the barrier to loop closing, ΔGc (Figure 3). However, the second-order rate constant for the reaction of the physiological substrate GAP will approach the “perfect” diffusion-controlled limit, provided conversion of the first-formed Eo•GAP complex by loop closing to give the catalytically active Ec•GAP complex and then to product is faster than dissociation of GAP from Eo•GAP. There is evidence that the closure of loop 6 over the substrate analog glycerol 3-phosphate is fast relative to the turnover of GAP,21 and that release of bound GAP from TIM is slower than its conversion to DHAP.2

The catalytic advantage to the inclusion of an unfavorable ligand-driven conformational change from Eo to Ec is that this provides a simple mechanism to attenuate the expression of the very strong enzyme-phosphodianion interactions at the Michaelis complex. This is necessary in order to avoid tight binding to TIM which could lead to slow, rate-determining, release of products.22 The observed 9-fold decrease in Km for the reaction of DHAP (Table 1) shows that the L232A mutation does in fact result in a larger expression of the binding interactions of DHAP at the Michaelis complex, at the expense of a decrease in kcat. The intrinsic binding energy of the substrates GAP and DHAP that is utilized to drive an unfavorable conformational change prior to product formation will not be expressed in the kinetic parameter Km. Rather, if the dianion-driven conformational change activates TIM for deprotonation of GAP then this binding energy will be expressed as stabilization of the transition state for deprotonation of bound substrate and an increase in kcat. The observation that the binding of phosphite dianion strongly activates TIM for catalysis of deprotonation of the substrate piece GA suggests that these dianion interactions also activate TIM for catalysis of deprotonation of GAP and DHAP.10,11,16

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Astrid P. Koudelka for the preparation of L232A mutant Tbb TIM and the National Institutes of Health Grant GM39754 for generous support of this work.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Procedure for preparation of L232A mutant Tbb TIM. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.The residues are numbered according to the sequence for the enzyme from Trypanosoma brucei brucei.

- 2.Knowles JR, Albery WJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1977;10:105–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rieder SV, Rose IA. J. Biol. Chem. 1959;234:1007–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wierenga RK. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:3961–3982. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gebbia JA, Backenson PB, Coleman JL, Anda P, Benach JL. Gene. 1997;188:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00811-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webster KA. J. Exper. Biol. 2003;206:2911–2922. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowles JR. Nature. 1991;350:121–124. doi: 10.1038/350121a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowles JR. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B. 1991;332:115–21. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1991.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amyes TL, O'Donoghue AC, Richard JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11325–11326. doi: 10.1021/ja016754a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5841–5854. doi: 10.1021/bi700409b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Go MK, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5769–5778. doi: 10.1021/bi900636c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alber T, Banner DW, Bloomer AC, Petsko GA, Phillips D, Rivers PS, Wilson IA. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B. 1981;293:159–71. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jogl G, Rozovsky S, McDermott AE, Tong L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:50–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0233793100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lolis E, Petsko GA. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6619–25. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davenport RC, Bash PA, Seaton BA, Karplus M, Petsko GA, Ringe D. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5821–6. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:702–710. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malabanan MM, Go M, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5767–5679. doi: 10.1021/bi2005416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kursula I, Wierenga RK. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9544–9551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borchert TV, Pratt K, Zeelen JP, Callens M, Noble MEM, Opperdoes FR, Michels PAM, Wierenga RK. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;211:703–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2610–2621. doi: 10.1021/bi047954c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desamero R, Rozovsky S, Zhadin N, McDermott A, Callender R. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2941–2951. doi: 10.1021/bi026994i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jencks WP. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1975;43:219–410. doi: 10.1002/9780470122884.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.