Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In order to support cancer patients, nurses need to identify different physio-psycho- social needs of patients using a holistic approach. Focusing on Quality of Life (QoL) is congruent with the philosophy of a holistic approach in nursing. The main aim of this research study thus was to identify the level of agreement between cancer patients and nurses about cancer patients’ QoL.

METHODS:

The study was a survey which was completed in 2008. 166 cancer patients and 95 nurses were conveniently recruited from three major hospitals in Adelaide, Australia. Each patient and nurse was invited to complete the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) questionnaire separately. This questionnaire considers QoL across four domains or dimensions: physical health, psychological health, social relationship and environment.

RESULTS:

The proportion of the exact agreement between the two groups was 34.9%, 34.5%, 33.8% and 36.9% for the physical, psychological, social relationship, and environmental QoL domains, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

Results may indicate that nurses do not have a holistic understanding of cancer patients’ QoL. QoL tools like the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) might be used as guidelines for nurses to assess cancer patients’ QoL rather than relying heavily on their perceptions and intuitions. The results provide some implications for Iran.

KEY WORDS: Nursing, quality of life, patients, oncology, nurses, world health organization, questionnaires

In the clinical area of cancer patients, the role of nurses is important as far as the supportive care of patients is concerned. In order to support cancer patients, nurses need to identify different physio-psycho-social needs of patients using a holistic approach.1,2 The philosophy of nursing invites nurses to nurture people to achieve holistic health and to adopt an approach that incorporates and integrates all aspects of their life into care decision making.3 Focusing on Quality of Life (QoL) is congruent with the philosophy of a holistic approach in nursing.4 Perceptions that nurses form about cancer patients’ QoL provide nurses with the best possible opportunity to identify needs, make decisions and select appropriate actions to be more therapeutic in their supportive roles and to improve patients’ QoL.5 Conversely, without a full understanding of patients’ QoL, decision making about patient care would not be optimal.6–8

Therefore, a reasonable degree of agreement needs to exist between the patients’ and nurses’ perceptions of cancer patients’ QoL. It might show if nurses are providing a holistic care to cancer patients. Given this, assessing the level of agreement between the cancer patients and the nurses over the patients’ QoL is considered important and worthy of investigation. The need for a research study comparing nurses’ and patients’ perceptions on QoL was further reinforced when it was identified that there is still a gap in the QoL research literature. Firstly, research studies in which the perceived QoL of cancer patients is compared with that of nurses across the world appear to be inconsistent in their outcomes. For example, nurses’ perceptions of cancer patients’ QoL are considered inaccurate in some research studies9–12 whereas others reported that such perceptions are reasonably correct.13–15 Generally, researchers recommend further studies to compare care providers’ ratings of patients’ QoL with that of patients’ own rating.16–19

Secondly, few research studies address the influence of major factors affecting agreement between patients and care providers adequately.19–23 As stated by several researchers,24,25 the findings of research studies have not been consistent and there is need for further research work. For example, in one research study, the degree of QoL agreement between patients and their care providers was influenced predominantly by the patients’ performance status.11 Another study yielded no evidence of such a relationship.26 Further research is necessary to identify the different variables affecting QoL agreement18–20 using more accurate statistical tests like the proportion of exact agreement.

Therefore, the main aim of this research study thus was to identify the level of agreement between cancer patients and nurses about cancer patients’ QoL.

Methods

This study is a survey by questionnaire which was completed in 2008 in Adelaide, South Australia. 166 cancer patients and 95 nurses were conveniently recruited to take part in the study. They were selected from three major hospitals and different wards including two specialist oncology wards, five non-specialist oncology wards, three outpatient chemotherapy units, one radiotherapy center and one palliative care area. Convenience sampling increased the variability in QoL ratings and allowed outcomes of the study to be generalized to a wider group of patients.26

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they had confirmed diagnosis of any kind of cancer, reached the age of 18 years or older, had the ability to read and write in English to be able to respond to the questionnaire appropriately, and agreed to participate in the study. Patients were selected from all inpatient and outpatient oncology centers and differed in their health status, disease severity and treatment modalities. All registered nurses who provided nursing care for a patient were eligible to take part if they stated that they knew the patient and consented to take part in the research study.

The principal researcher introduced the research study to each patient-nurse pair. If they agreed to take part in the study, the principal investigator gave the patient the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) questionnaire to complete and the nurse then filled out a World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) separately, based on his/her understanding of the patient's QoL. The questionnaire was generally completed by nurses on the same day at a time which was suitable for them (in work hours, rest time or after work) based on their perceptions of cancer patients’ QoL. However, there were very limited cases (less than 10) that nurses filled out the forms relating to their patients a day later than the patients due to busy environment and their related tasks. The nurses were not allowed to ask the patients any questions specific to the questionnaire, before filling out their own questionnaire but instead were to refer to the medical or nursing records.

This research was approved by the appropriate Clinical Research Ethics Committees of three hospitals. The same number was recorded on a patient's and nurse's characteristic form as well as the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) questionnaire, to be completed by patients and nurses, so that the information from the patient's and nurse's forms were able to be properly matched and the data compiled, while participant's anonymity was assured. Verbal and written information about the research project was provided for both patients and nurses. Agreement to complete the questionnaire was considered as consent for both patients and nurses and they were informed that this was the case, as well as of their right to withdraw from the study at any time if they desired so. In order to deal with patients’ possible emotional distress, supportive care in the form of counselling was negotiated with the Clinical Nurse Consultant. Nurses were not expected to experience any emotional stress by filling out a QoL questionnaire for patients.

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) questionnaire was used for this research. This test uses 26 items which assess the QoL for four domains or dimensions, including physical (7 items), psychological (6 items), social relationship (3 items), and environmental (8 items) domains, as well as 2 items measuring overall quality of life and general health. All 26 items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale.27

As the WHO group27 stated, the internal consistency of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) ranges from 0.66 in the social relationship domain to 0.84 in the physical domain and test-retest reliability of the tool is 0.75 for all domains. All above mentioned correlations fall within intervals 0.61-0.80 and 0.81-1.00 which indicate almost substantial and perfect associations, respectively.28

As suggested,19,25,29 one of the main statistical tests used in this study to measure the level of agreement between cancer patients and nurses was the proportion of exact agreement. Exact agreement is defined as those cases where the response category chosen by the patient and the nurse for a given item is identical.30

Results

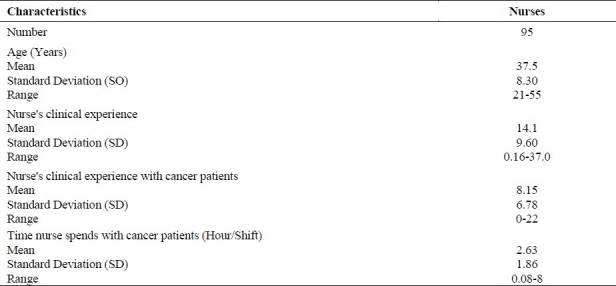

The demographic variables of nurses are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of nurses based on their number, their clinical experience and time they spent with cancer patients/shift

95 nurses took part in the research study with the average age of 37.5 (8.30 SD), ranging from 21 to 55. The mean time the nurse spent for providing care for a given patient (hour/shift) was 2.63 (1.86 SD) with a range of 0.08-8 hour. The mean clinical experience of nurses was 14.1 years (9.60 SD) with a range of 0.16-37 years. The nurses’ mean clinical experience with cancer patients was 8.15 years (6.78 SD) with a range of 0-22 years. The patients had a range of cancer diagnoses with breast cancer being the most prevalent. Most of the patients were being treated as inpatients with chemotherapy being their primary treatment.

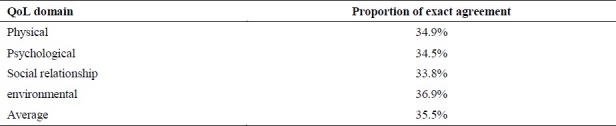

The proportion of exact agreement between patients and nurses for different QoL domains of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) questionnaire is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The proportion of exact agreement for different QoL domains between patients and nurses

These data show that the average proportion of exact agreement between patients and nurses is 35.5%. The proportion of the exact agreement between the two groups was 34.9%, 34.5%, 33.8%, and 36.9% for the physical, psychological, social relationship, and environmental QoL domains.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to measure the level of agreement between cancer patients and nurses about cancer patients’ QoL. The level of agreement between QoL ratings of patients and nurses may show if nurses have a holistic understanding of patients’ QoL. The proportion of the exact agreement identified that in 35.5% of cases a similar response category had been chosen by both patients and nurses in the questionnaire. It means that, for example, in answering item one in the questionnaire, 35.5% of both patients and nurses chose the category ′satisfied’ or ′very satisfied’ for that item. Previous research studies14–30 suggest that at least 60% of agreement between patients and proxies in QoL tool items is satisfactory. Therefore, 35.5 % was not considered a substantial agreement because it is far from the acceptable level (60%).

These findings are similar to general trends found in many other research studies in which the level of agreement between patients and other care providers including nurses was assessed using QoL tools other than the WHOQoL questionnaires.31–33 The outcomes are also very similar to two following research studies34,35 in which the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief questionnaires (WHOQoL-BREF or WHOQoL-100) were used but with populations other than cancer patients.

Herrman, Hawthorne and Thomas35 in their research study in Australia compared psychosis patients and their case managers as patients’ proxies using a set of questionnaires including the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) questionnaire. Results identified that scores of the case managers and patients correlated moderately, correlations ranged from 0.31 in the social domain up to 0.47 in the physical domain. Their research study concluded that a significant difference exists between patients and proxies. These outcomes are generally supported by another research study conducted by Becchi et al34 in which QoL of patients with schizophrenia was compared by proxies using the WHOQoL- 100 questionnaire. Of the proxies, 52.7% were relatives whereas 47.3% were non-relatives (e.g. friends, social workers, and nurses). The outcomes of Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) ranged between 0.26 for the psychological area to 0.42 for the physical area, indicating a poor agreement between patients and proxies.

The above results are in contrast with some other research findings. For example, in a research study conducted by Sneeuw et al15 QoL of cancer patients was assessed and compared with the perspectives of significant others, physicians, and nurses using a QoL tool. Part of the outcomes identified that 41 % of all comparisons were in exact agreement. While the level of agreement was far from 60%, the authors concluded that “judgments made by significant others and professional caregivers about general aspects of cancer patients’ QoL are reasonably accurate”. Authors of this article explained that these interpretations were based on calculations of the proportion of approximate (global) agreement as well as the proportion of exact agreement. In calculating the proportion of approximate (global) agreement, when both patients’ and nurses’ responses differ from each other along the response scale by one category in either direction, differences can be interpreted as small. Only differences of more than one category are considered large. The proportion of approximate (global) agreement in Sneeuw's study15 was 43% and along with outcomes of the exact agreement (41%), it was concluded that a reasonable level of agreement exists between patients and nurses.

Altogether it might be concluded that nurses do not have a holistic understanding of cancer patients’ QoL. However, other underlying reason for differences between perceptions of cancer patients and nurses about cancer patients’ QoL can be seen in the manner that nurses actually assess QoL for their patients. Nurses generally appear to assess the QoL of patients more informally during interactions with them rather than through the application of QoL tools. Moreover, the state of QoL might change over the time and that is relatively dependent on individual priorities and feelings. QoL tools may not be able to identify these changes unless they are performed longitudinally and frequently, and often this is not practical.

When a nurse differs in their perceptions of each patient's QoL, it is most likely that their decisions do not meet a patient's needs in all aspects. Conversely, when a nurse has a reasonable understanding of a cancer patient's QoL, their decision making can better follow a patient's needs. In turn, the nursing care they will provide may improve patients’ QoL and care can be more individualised.5 Therefore, this supports a need for nurses to develop a more holistic relationship and stronger rapport with patients. QoL tools like the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) might also be used as guidelines for nurses to assess cancer patients’ QoL rather than relying heavily on their perceptions and intuitions.

The findings of this research study must be interpreted within its limitations. Firstly, an attempt was made to include as many nurses as possible in the research study;36 however, like other research studies,29,32 the number of nurses included was around half of patients. Secondly, the study was conducted in a very busy oncology environment and on some occasions this may have affected the nurses’ concentration while completing the questionnaires.

Even though the research study is conducted in Australia, research outcomes might be still relevant to Iran. In this research study, the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQoL-BREF) questionnaire was chosen. This questionnaire has been developed across different countries and the dimensions that are covered by this tool may be broad enough to cover many QoL issues that are relevant to both countries, i.e. Australia and Iran. Some empirical outcomes of the research study therefore might have external validity and are generalized to Iran, but with necessary cautions. It is suggested that a similar research study should be conducted in Iran and results then be compared with other countries like Australia. Comparing QoL across different countries in the shape of cross-cultural research trials is one important line of research for investigators. This would help, for instance, to explore if cancer patients in a developed country like Australia have a better state of QoL compared with a developing country like Iran and what would be the underlying reasons. Such research studies would be very useful particularly for improving the health systems.

The author declare no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- 1.Rebollo P, Alvarez-Ude F, Valdes C, Estebanez C. Different evaluations of the health related quality of life in dialysis patients. J Nephrol. 2004;17(6):833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tallis K. How to Improve The Quality of Life in Patients Living with End Stage Renal Failure. Renal Society of Australia Journal. 2005;1(1):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson HC, Tomlin E, Swain M. Modeling and Role-Modeling: A Theory and Paradigm for Nursing. Prentice Hall. 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 4.King CR, Hinds P, Dow KH, Schum L, Lee C. The nurse's relationship-based perceptions of patient quality of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(10):E118–26. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.E118-E126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King CR. Advances in how clinical nurses can evaluate and improve quality of life for individuals with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(1 Suppl):5–12. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.S1.5-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickard AS, Knight SJ. Proxy evaluation of health-related quality of life: a conceptual framework for understanding multiple proxy perspectives. Med Care. 2005;43(5):493–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160419.27642.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nekolaichuk CL, Bruera E, Spachynski K, MacEachern T, Hanson J, Maguire TO. A comparison of patient and proxy symptom assessments in advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 1999;13(4):311–23. doi: 10.1191/026921699675854885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King CR, Ferrell BR, Grant M, Sakurai C. Nurses’ perceptions of the meaning of quality of life for bone marrow transplant survivors. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18(2):118–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao H, Kanda K, Liu SJ, Mao XY. Evaluation of quality of life in Chinese patients with gynaecological cancer: assessments by patients and nurses. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9(1):40–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172x.2003.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slevin ML, Plant H, Lynch D, Drinkwater J, Gregory WM. Who should measure quality of life, the doctor or the patient? Br J Cancer. 1988;57(1):109–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton R. Differences in assessment of symptoms and quality of life between patients with advanced cancer and their specialist palliative care nurses in a home care setting. Palliat Med. 2002;16(6):488–94. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm588oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunelli C, Costantini M, Di Giulio P, Gallucci M, Fusco F, Miccinesi G, et al. Quality-of-life evaluation: when do terminal cancer patients and health-care providers agree? J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15(3):151–8. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geddes DM, Dones L, Hill E, Law K, Harper PG, Spiro SG, et al. Quality of life during chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer: assessment and use of a daily diary card in a randomized trial. Eur J Cancer. 1990;26(4):484–92. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(90)90022-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisch MJ, Titzer ML, Kristeller JL, Shen J, Loehrer PJ, Jung SH, et al. Assessment of quality of life in outpatients with advanced cancer: the accuracy of clinician estimations and the relevance of spiritual well-being--a Hoosier Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(14):2754–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, Detmar SB, Wever LD, Schornagel JH. Evaluating the quality of life of cancer patients: assessments by patients, significant others, physicians and nurses. Br J Cancer. 1999;81(1):87–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPherson CJ, Addington-Hall JM. Judging the quality of care at the end of life: can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(1):95–109. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickard AS, Johnson JA, Feeny DH, Shuaib A, Carriere KC, Nasser AM. Agreement between patient and proxy assessments of health-related quality of life after stroke using the EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index. Stroke. 2004;35(2):607–12. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110984.91157.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampic C, Sjoden PO. Patient and staff perceptions of cancer patients’ psychological concerns and needs. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(1):9–22. doi: 10.1080/028418600430923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang ST, McCorkle R. Use of family proxies in quality of life research for cancer patients at the end of life: a literature review. Cancer Invest. 2002;20(7-8):1086–104. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120005928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Essen L. Proxy ratings of patient quality of life--factors related to patient-proxy agreement. Acta Oncol. 2004;43(3):229–34. doi: 10.1080/02841860410029357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novella JL, Jochum C, Jolly D, Morrone I, Ankri J, Bureau F, et al. Agreement between patients’ and proxies’ reports of quality of life in Alzheimer's disease. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(5):443–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1012522013817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sands LP, Ferreira P, Stewart AL, Brod M, Yaffe K. What explains differences between dementia patients’ and their caregivers’ ratings of patients’ quality of life? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):272–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, Hebel JR. Patient-proxy response comparability on measures of patient health and functional status. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1065–74. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sneeuw KC, Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK. The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(11):1130–43. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lobchuk MM, Degner LF. Patients with cancer and next-of-kin response comparability on physical and psychological symptom well-being: trends and measurement issues. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25(5):358–74. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, Detmar SB, Wever LD, Schornagel JH. Value of caregiver ratings in evaluating the quality of life of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):1206–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, Detmar SB, Wever LD, Schornagel JH. Comparison of patient and proxy EORTC QLQ-C30 ratings in assessing the quality of life of cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(7):617–31. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Osoba D, Muller MJ, Hsu MA, Yung WK, et al. The use of significant others as proxy raters of the quality of life of patients with brain cancer. Med Care. 1997;35(5):490–506. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199705000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson KA, Dowling AJ, Abdolell M, Tannock IF. Perception of quality of life by patients, partners and treating physicians. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(9):1041–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1016647407161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molzahn AE, Northcott HC, Dossetor JB. Quality of life of individuals with end stage renal disease: perceptions of patients, nurses, and physicians. ANNA J. 1997;24(3):325–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsson G, von Essen L, Sjoden PO. Quality of life in patients with endocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: patient and staff perceptions. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21(6):411–20. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becchi A, Rucci P, Placentino A, Neri G, de Girolamo G. Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia--comparison of self-report and proxy assessments. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(5):397–401. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrman H, Hawthorne G, Thomas R. Quality of life assessment in people living with psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(11):510–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0587-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broberger E, Tishelman C, von Essen L. Discrepancies and similarities in how patients with lung cancer and their professional and family caregivers assess symptom occurrence and symptom distress. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(6):572–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]