Abstract

As the neural network becomes wired postsynaptic signaling molecules are thought to control the growth of dendrites and synapses. However, how these molecules are coordinated to sculpt postsynaptic structures is less well understood. We find that ephrin-B3, a transmembrane ligand for Eph receptors, functions postsynaptically as a receptor to transduce reverse signals into developing dendrites of murine hippocampal neurons. Both tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent Grb4 SH2/SH3 adaptor-mediated signals and PDZ domain-dependent signals are required to inhibit dendrite branching, while only PDZ interactions are necessary for spine formation and excitatory synaptic function. Pick1 and syntenin, two PDZ domain proteins, participate with ephrin-B3 in these postsynaptic activities. Pick1 plays a specific role in spine/synapse formation, while syntenin promotes both dendrite pruning and synapse formation to build postsynaptic structures essential for neural circuits. The study thus dissects ephrin-B reverse signaling into three distinct intracellular pathways and protein-protein interactions that mediate the maturation of postsynaptic neurons.

Keywords: ephrin-B3, reverse signaling, SH2, PDZ, Grb4, Pick1, syntenin, syndecan, hippocampus, dendrites, spine formation, synapse

During brain development neurons wire together by axon-dendrite contact and the initial connections of nerve terminals with dendritic protrusions are thought to initiate the formation of excitatory synapses. While a number of cell surface receptors, cell adhesion molecules, and intracellular cytoskeletal regulators have been implicated in the formation of neural circuits 1,2, how these molecules signal and coordinate their activities in vivo remains poorly understood.

Recent studies have showed Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and their membrane-anchored ephrin ligands play critical roles in neuronal connectivity and excitatory synapse formation upon axon-dendrite contact 1,3,4. The Eph family is the largest group of receptor tyrosine kinases and is divided into two subfamilies, termed EphA and EphB. Their ephrin ligands are also attached to the plasma membrane either through a glycosylphosphatidylinositol linkage (ephrin-A) or by a hydrophobic transmembrane domain (ephrin-B) that is followed by a short, highly conserved cytoplasmic tail that becomes tyrosine phosphorylated and can associate with both SH2 and PDZ domain-containing proteins 5. Key features of EphB/ephrin-B interactions are their ability to transduce signals bidirectionally into both the EphB-expressing cells (forward signaling) and ephrin-B-expressing cells (reverse signaling) upon cell-cell contact 6,7, and their ability to play diverse roles in a wide array of developmental and adult processes 8.

EphB receptors are known to be expressed in dendrites and transduce postsynaptic forward signals that promote the assembly, maturation, and plasticity of synapses 1,3,4. Ephrin-Bs are expressed in both axons and dendrites, and as a presynaptic player can function as the ligand to induce postsynaptic EphB forward signaling 9–12 as well as a receptor to transduce reverse signals important for axon guidance and pruning 6,13,14, presynaptic development 15, and plasticity of mossy fiber-CA3 and retinal-tectal synapses 16,17. While much less understood, ephrin-B proteins expressed in the postsynaptic compartment have been implicated in synapse formation in cultured neurons 18–20 and synaptic plasticity of the Schaffer/CA3-CA1 circuit in the fully developed adult brain 21–25. However, as a postsynaptic player, the roles of ephrin-Bs as revealed using in vitro cultured neuron-based assays remain ambiguous, and the involvement of reverse signals in vivo in developing dendrites and spines are largely unknown even though ephrin-B3 (throughout called eB3) is expressed to high levels in the dendritic field of certain neurons (see below). We thus hypothesized that postsynaptic eB3 may be able to transduce reverse signals into dendrites necessary for the early development of synaptic structures. Here we report our in vivo analysis of gene targeted mutant animals that shows eB3 transduces tyrosine phosphorylation/SH2-dependent and PDZ-dependent reverse signals to bring about morphogenesis of the postsynaptic compartment.

RESULTS

Ephrin-B3 reverse signaling shapes dendrites and spines

We used the Thy1-GFP-M transgenic mouse 26 to visualize a subset of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons during the critical postnatal period (P9 to P20), and observed that the development of dendrites in wild-type (WT) mice proceeds through initial elongation and pruning of primary branches that extend from the cell body, subsequent branching of secondary dendritic arbors, and finally the formation of spines and synapses (Supplementary Fig. 1). The Allen Developing Mouse Brain Atlas expression database shows the ephrin-B3 gene (Efnb3), encoding one of the transmembrane ligands for Eph receptors, is specifically and highly expressed in CA1 pyramidal neurons (Supplementary Fig. 2). We further analyzed the expression of eB3 protein in CA1 area throughout postnatal development (P7–42) using X-gal staining of brain sections from mice carrying the Efnb3lacZ reporter knock-in mutation (Efnb3lacZ/+) 27. This mutation encodes a membrane localized C-terminal truncated ephrin-B3-β-galactosidase (eB3-β-gal) fusion protein that is expressed in the correct temporal, spatial, and subcellular pattern as the endogenous WT protein and provides for a high signal-to-noise ratio reporter. Our analysis revealed that while eB3-β-gal was barely detected at P7, it strongly and specifically labeled the dendritic field of CA1 pyramidal cells afterwards (Fig. 1a). This eB3 expression is colocalized with PSD-95, a postsynaptic marker in cultured hippocampal neurons (Supplementary Fig. 3). The data is consistent with the Allen Brain Atlas database (Supplementary Fig. 2) and previous studies 21,22,24,25 that indicated a postsynaptic role in the mature adult brain for ephrin-B2 (eB2) and eB3 proteins in mediating synaptic plasticity of the Schaffer/CA3-CA1 circuit. Although roles for ephrin-B1 (eB1) mediated reverse signaling have also been implicated in the dendrites of cultured hippocampal neurons 20, expression of the ephrin-B1 gene (Efnb1) is undetectable in the developing and adult hippocampus as shown in the Allen Brain Atlas database (Supplementary Fig. 2).

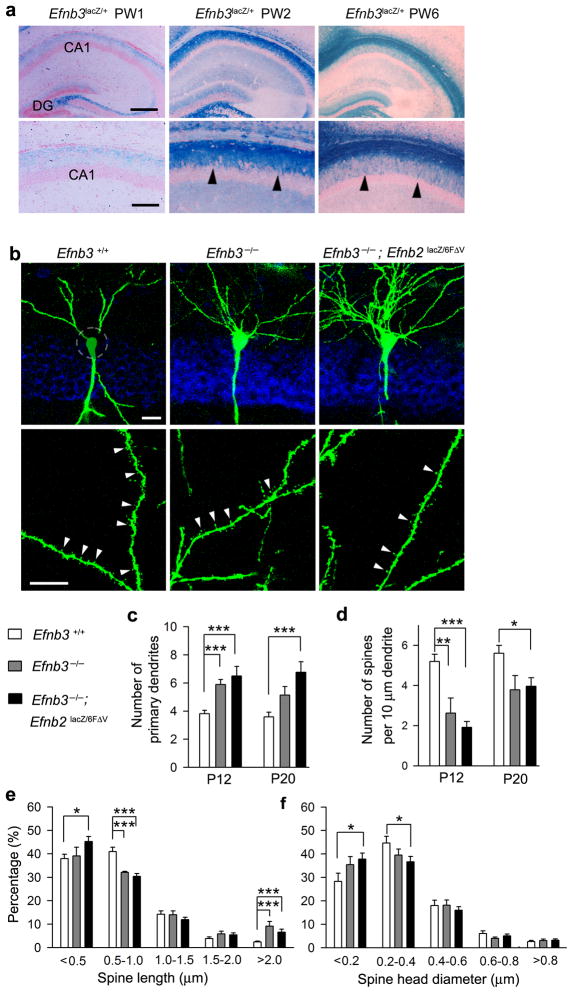

Figure 1. Ephrin-B3 is required for dendrite pruning and spine formation in hippocampal CA1 neurons.

(a) Developmental expression of eB3 in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer visualized by X-gal staining of coronal sections for the eB3-β-gal fusion protein (blue) in Efb3lacZ mice from one week (PW1) to six weeks age (PW6). Structure of the hippocampus is visualized by eosin counterstaining (red). Arrowheads indicate the localization of eB3 protein in the CA1 dendritic field. There is also strong expression of eB3 in granule cells of the dentate gyrus (DG) where the eB3-β-gal fusion localizes to mossy fiber axons and dendrites. Scale bars, 300 μm in the upper panel and 150 in the lower panel. (b) Efnb3−/− null and Efnb3−/−;Efnb2lacZ/6FΔV mutants at postnatal day 12 (P12) showed excessive dendrites and reduced spine density in CA1 pyramidal neurons. White circle in the upper left panel indicates the crossed primary dendrites. Green: Thy1-GFP-M fluorescence; Blue: neurotrace to stain CA1 pyramidal cell layer. Scale bars, 20 μm in upper panel and 10 μm in lower panel. (c, d, e, f) Quantification of primary dendrites (c), spine density (d), spine length (e) and spine head diameter (f) in wild-type (WT), Efnb3−/− null, and Efnb3−/−;Efnb2lacZ/6FΔV mutants at P12 and P20 (n = 12 per group). Mean ± s.e.m. * P < 0.05; ** P< 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

To determine if eB3 has a role in the initial development of dendrites and synapses, we examined the early morphological changes of dendritic branches and the density of spines along the dendrites in various Efnb mutants crossed with the Thy1-GFP-M transgenic mouse line to label a subset of CA1 neurons (Fig. 1b). The neurons in Efnb3−/− null mice showed a significant increase in the number of primary dendrites and total dendritic branches compared to the Efnb3+/+ WT littermates at P12 (Fig. 1c,d and Supplementary Fig. 1). This result was confirmed using Golgi stain (Supplementary Fig. 4), and together these two methods indicate eB3 negatively regulates dendrite growth and arborization of the developing CA1 pyramidal neurons. We carefully examined the postnatal time course of dendrite arborization in the CA1 pyramidal neurons of WT and Efnb3−/− null mutants (Supplementary Fig. 1). The data showed there are approximately 50% more primary dendrites extending from WT neurons at early postnatal days (i.e. P9) than what is observed at later stages (P12 to P20), indicating exuberant processes normally become eliminated/pruned between P9 and P12. In contrast, the number of primary dendrites in Efnb3−/− mice did not become reduced at later postnatal stages. The Efnb3−/− mice also showed more total dendritic branches at P12 compared to the WT controls, however both mutant and WT groups eventually reached a stable level after P16 when no significant difference was noted between the two groups. As WT and Efnb3−/− mutant mice both showed similar numbers of primary dendrites at P9, we conclude that the initial outgrowth of dendrites is not affected by the lack of eB3 expression. However, the failure to eliminate exuberant primary dendrites observed in the Efnb3−/− mutant as the animal ages indicates a role for eB3 in postnatal pruning of dendritic branches.

We next asked whether the cytoplasmic domain of eB3 is required for dendritic pruning. As described previously 27, the Efnb3lacZ mutation expresses a truncated eB3-β-gal fusion protein that retains the extracellular and transmembrane domains to provide ligand-like activities to initiate forward signaling, but lacks the cytoplasmic segment and thus cannot transduce reverse signals. Efnb3lacZ/lacZ mutants showed approximately 50% more primary dendrites and total dendritic branches that were similar to the Efnb3−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 5), suggesting the role of eB3 in dendrite elimination is due to its ability to act like a receptor and transduce reverse signals. We next generated compound mutants using Efnb2lacZ (C-terminal truncated 28) and Efnb26FΔV (point mutant eliminating both SH2 and PDZ binding 29) alleles that interfere with reverse signaling of the related eB2 protein, which is also expressed in CA1 neurons (Supplementary Fig. 2). The analysis showed Efnb3−/−;Efnb2lacZ/6FΔV compound mutants null for Efnb3 and reverse signaling mutant for Efnb2 exhibited an enhanced phenotype with even more primary dendrites, especially noted at P20 (Fig. 1b,c).

The Thy1-GFP-M transgene also allowed for analysis of dendritic spines on the CA1 neurons in the various mutants (Fig. 1b, lower panels). In contrast to the increase in primary dendrites and dendritic branches, the density of spines was greatly reduced in mutants analyzed at P12 compared to that of WT (Fig. 1d). In WT neurons most spines are mushroom shaped (thin neck and large head) while spines in the mutant have protrusions with smaller head diameter and different length of either very short (< 0.5 μm) or very long (> 2 μm) (Fig. 1e,f), suggesting the change in density of spines is attributable to an alteration of spine maturation. The strongest reduction in spine density was noted in the Efnb3−/−; Efnb2lacZ/6FΔV compound mutants, where significant differences with WT remained even at P20. This data is consistent with a role for ephrin-B reverse signaling in neuron maturation.

As EphB receptors are highly expressed in CA3 pyrimadal neurons 14, it raises the question if these molecules act as ligands to stimulate ephrin-B reverse signaling for CA1 maturation. We therefore analyzed dendritic morphogenesis in protein-null mutants of EphB1, which is specifically expressed in CA3 neurons, and compound knockouts of both EphB1 and EphB2 to determine if these molecules are biological partners for eB3 (Supplementary Fig. 6). We found increased CA1 branches and less matured spines in EphB1−/− single mutants and an even more severe phenotype in EphB1−/−; EphB2−/− compound mutants, suggesting that EphB molecules are important for dendrite elimination and spine maturation. Interestingly, the deficit was recovered in EphB1−/−; EphB2lacZ/ lacZ mice to the level of EphB1−/− single mutants, indicating that the intracellular segment of EphB2 is not required. These data confirms the results with eB3 mutants, and indicates the role for EphB receptors here is to act as CA3-expressed ligands to stimulate ephrin-B reverse signals into dendrites of CA1 neurons.

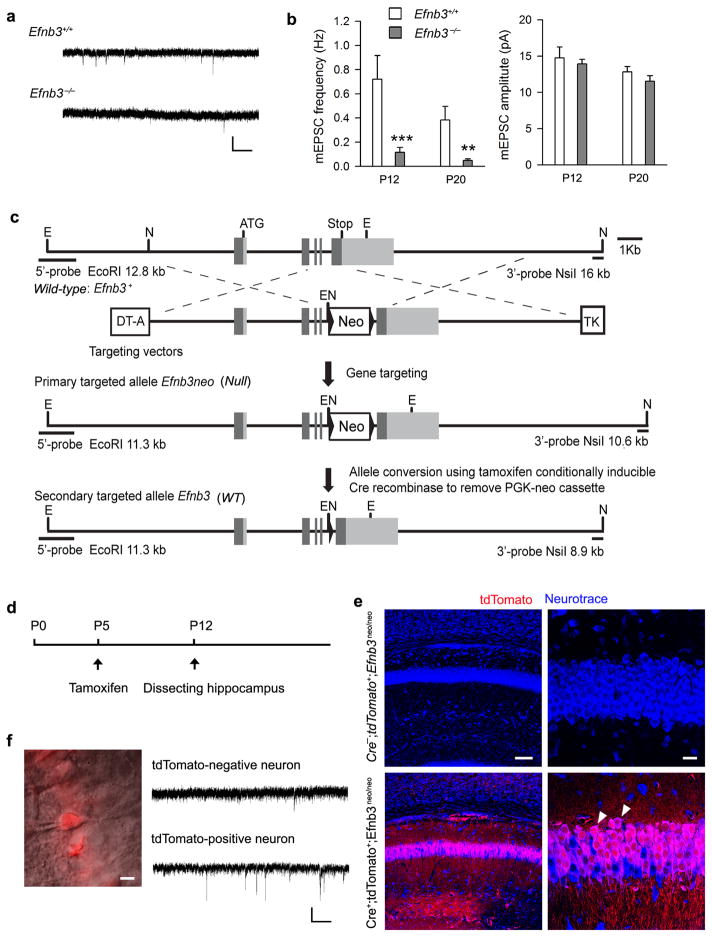

Ephrin-B3 is required and sufficient for synaptic function

We next examined the role of eB3 in synaptic function by performing whole-cell voltage clamp recordings in brain slices collected at P12 and P20 to assess spontaneous miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) occurring in CA1 pyramidal neurons in acute WT and Efnb3 mutants. Spontaneous mEPSCs are a measurement of the random release of presynaptic vesicles at different synaptic sites and are used to assess numbers of functional synapses. Although no significant change in amplitude was observed, both Efnb3−/− (Fig. 2a,b) and Efnb3lacZ/lacZ mutants (data not shown) exhibited a greatly reduced mEPSC frequency compared to the WT (17.5% and 34.1%, respectively). Combined with the morphological data that indicated reduced numbers of dendritic spines in the mutants (Fig. 1d), the electrophysiology confirms a reduction in the number of functional Schaffer/CA3-CA1 synapses in the absence of postsynaptic eB3 reverse signaling.

Figure 2. Ephrin-B3 is required and sufficient for excitatory synaptic function in hippocampal CA1 neurons.

(a,b) Efnb3−/− null mutant showed reduced mEPSC frequency in CA1 pyramidal neurons at P12 (a) and P20. Scale bar: 20 pA (vertical) × 1 s (horizontal). Mean ± s.e.m. ** P< 0.01; *** P < 0.001. (c) Generation of conditional floxed knock-in Efnb3neo mutant. Exons (coding/ non-coding segments are dark/ gray filled boxes) and introns (lines) are flanked by a diphtheria toxin (DT-A) and thymidine kinase (TK) expression cassette for negative selection. E (EcoRI) and N (NsiI) indicate restriction sites. The primary targeted allele, Efnb3neo homozygous was crossed with CAGG-CreERT2M driver and a tdTomato reporter to identify cells exposed to active Cre. eB3 expression in the initial Efnb3neo/neo null is restored upon tamoxifen administration to induces Cre-mediated excision of the loxP-flanked PGK-neo cassette. (d) Schedule of tamoxifen treatment and hippocampus dissection during postnatal development. (e) Cre-mediated recombination in CA1 area was detected in P12 hippocampal sections by td-Tomato fluorescence (arrowheads) in Cre+; tdTomato+; Efnb3neo/neo mice but not in Cre−; tdTomato+; Efnb3neo/neo mice following tamoxifen administration at P5. Scale bar: 100 μm in the left panel and 20 μm in the right panel. (f) mEPSC recording were performed in tdTomato positive (indicated by a glass electrodes) and negative neurons in hippocampal CA1 area of Cre+; tdTomato+; Efnb3neo/neo mice after tamoxifen treatment. Scale bar: 10 μm for the left panel and 20 pA (vertical) × 1 s (horizontal) for the right panel.

To further investigate the sufficiency of eB3 in synaptic development, we designed an experiment to rescue expression of eB3 in a genetically null mouse. To accomplish this, a conditional knock-in mouse line was generated, termed Efnb3neo, by inserting a loxP-flanked PGK-neo cassette into the intron between the forth and the fifth exons of Efnb3 (Fig. 2c). We previously used a similar strategy in our original generation of Efnb3 mutations 27 and showed that such an insertion results in a protein-null allele as judged by a hopping locomotion in adult homozygotes. Efnb3neo/neo mice containing an ubiquitous CAGG-CreERT2M transgene 30 and a floxed-Stop tdTomato reporter 31 (Cre+;tdTomato+;Efnb3neo/neo) were treated with tamoxifen at P5 (Fig. 2d,e) or at P8 (Supplementary Fig. 7) to activate Cre recombinase and delete the PGK-neo cassette which allowed eB3 expression, for our purpose, in a subset of CA1 pyramidal neurons. At P12 mEPSCs were recorded from tdTomato-positive, which indicates eB3 rescued, or negative CA1 neurons in acute brain slices (Fig. 2f). The frequency of mEPSCs in tdTomato-positive neurons (0.52 ± 0.08 Hz), that was treated with tamoxifen at P5, was significantly higher than that of the tdTomato-negative neurons (0.11 ± 0.03 Hz), with no difference observed in amplitude between two groups (Fig. 2f). Thus, eB3 expression initiated at P5 is sufficient to rescue the Schaffer/CA3-CA1 synaptic defects associated with the mutants.

SH2 and PDZ binding mediate ephrin-B3 reverse signals

Reverse signaling mediated by ephrin-B proteins may involve at least two distinct pathways governed by the ability of its intracellular domain to form protein-protein interactions with both SH2 and PDZ domain-containing intracellular proteins. Following interactions with their cognate EphB receptors (and EphA4) and formation of circular tetramers and higher order clusters, the ephrin-B cytoplasmic tail becomes tyrosine phosphorylated and recruits the SH2/SH3 adaptor protein Grb4 32 to bridge the ephrin-B molecule with a number of intracellular proteins including the Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor Dock180 and downstream effector Pak1 (Ref. 14). The ephrin-B proteins also bind numerous PDZ domain proteins through their conserved C-terminal tail 5. As shown in Fig. 3a, we generated germline point mutations in the Efnb3 gene that eliminate either tyrosine phosphorylation, termed Efnb33F and Efnb35F (Ref. 14), or/and the PDZ interaction motif by deleting the extreme C-terminal valine residue essential for PDZ binding, which are termed Efnb3ΔV and Efnb33FΔV, respectively (Supplementary Fig.8a,b). Using these mutations, we aimed to precisely determine which signals eB3 needs to transduce into the CA1 neurons for dendritic morphogenesis and synaptic transmission.

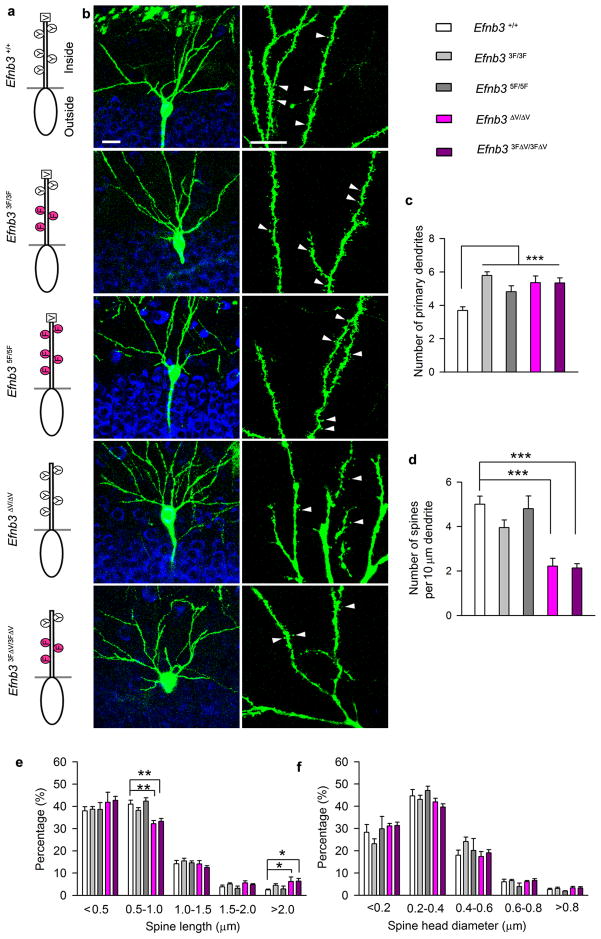

Figure 3. Ephrin-B3 tyrosine phosphorylation and PDZ binding are differentially required for dendrite morphogenesis and synaptic function.

(a) Point mutations in the Efnb3 gene that eliminate tyrosine phosphorylation and SH2 binding (3F and 5F), PDZ binding (ΔV), or both SH2 and PDZ binding (3FΔV). (b) Thy1-GFP-M fluorescence (green) was used to visualize the morphology of CA1 neurons at P12. Scale bar: 20 μm for left panels and 10 μm for right panels. (c, d, e, f) Quantification of primary dendrites (c), spine density (d), spine length (e) and spine head diameter (f) in WT, Efnb33F/3F, Efnb35F/5F, Efnb3ΔV/ΔV, and Efnb33FΔV/3FΔV mutants at P12 (n = 25 per group). Mean ± s.e.m, **, P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

As expected, the new Efnb3ΔV and Efnb33FΔV mutations were found to be viable as homozygotes at Mendelian ratios and the adults appeared healthy, fertile and long lived as previously shown for all the other Efnb3 mutants. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed that all the mutants have similar Efnb3 mRNA level compared to that of WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Importantly, like the previously described Efnb3lacZ/lacZ, Efnb33F/3F, and Efnb35F/5F mutants, the Efnb3ΔV/ΔV and Efnb33FΔV/3FΔV adults also exhibit normal locomotion (as opposed to the Efnb3−/− mice which show a hopping gait), indicating all these mutations express proteins that traffic to the plasma membrane and can still function as ligands to stimulate Eph forward signaling important for locomotor circuitry 27. In order to confirm the plasma membrane localization of the new eB3mutant proteins, primary hippocampal neurons from WT, Efnb3−/−, Efnb33F/3F, Efnb35F/5F, Efnb3ΔV/ΔV and Efnb33FΔV/3FΔV mice were cultured for 12 days and cell surface proteins were labeled with biotin 6. Biotinylated proteins were then pulled down from lysates with streptavidin and immunoblotted with anti-eB3 antibodies revealing all mutants expressed eB3 protein on the cell surface (Supplementary Fig. 8d). We then exposed neuron cultures to soluble preclustered EphB2-Fc extracellular domains, and observed obvious tyrosine phosphorylation of eB3 in neurons from WT and Efnb3ΔV/ΔV cultures (Supplementary Fig. 9a), but not Efnb35F/5F or Efnb33F ΔV/3FΔV neurons. Further, while cultures from WT or Efnb35F/5F mice showed clear co-localization of the PDZ domain-containing protein Pick1 with eB3, this was not observed in Efnb3ΔV/ΔV or Efnb33F ΔV/3FΔV neurons (Supplementary Fig. 9a). We further tested for a physical interaction between eB3 and Pick1 using co-immunoprecipitation from brain protein lysates. The data showed that eB3 was co-immunoprecipitated with Pick1 from WT or Efnb35F/5F but not that from Efnb3ΔV/ΔV or Efnb33FΔV/3FΔV mutants (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Therefore, while the Efnb3ΔV and Efnb33F ΔV mutations do express their respective eB3-ΔV and eB3-3FΔV proteins on the surface of hippocampal neurons and can be clustered by EphB-Fc treatment, they are not able to interact with PDZ domain-containing proteins.

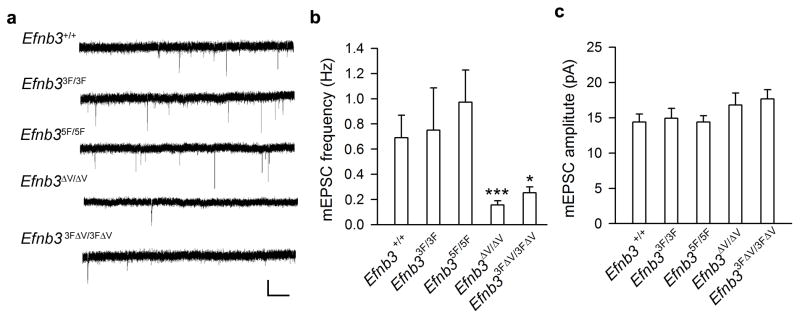

Dendritic morphogenesis of the various Efnb3 point mutants was then visualized using the Thyl-GFP-M transgene at P12 to determine the roles of distinct signaling motifs of eB3 in arborization and spine formation. All the Efnb3 point mutants showed similar excessive primary dendritic branches comparable to that of the Efnb3−/− or EfnbB3lacZ/lacZ homozygotes, while only the Efnb3ΔV/ΔV and Efnb33FΔV/3FΔV mutantsshowed reduced spine density along the dendrites (Fig. 3b–d). In the mutants with valine deleted, the percentage of matured spines (0.5–1μm) was significantly decreased whereas that of long dendritic protrusions (> 2.0 μm) was significantly increased (Fig. 3e–f). Recordings of Schaffer/CA3-CA1 synapses in P12 brain slices revealed that the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs in Efnb33F/3F and Efnb35F/5F mutants were not significantly different from that of WT littermates. However, both Efnb3ΔV/ΔV and Efnb33FΔV/3FΔV mutantsshowed a reduced mEPSC frequency with no change in amplitude (Fig. 4). This data indicates that both tyrosine phosphorylation and PDZ interactions of the eB3 cytoplasmic tail are required for normal pruning of developing dendrites, and that only PDZ binding activities are essential for the development of spines and normal synaptic activity.

Figure 4. PDZ binding of ephrin-B3 are required for synaptic function.

(a) mEPSCs were recorded in CA1 pyramidal neurons from WT, Efnb33F/3F, Efnb35F/5F, Efnb3ΔV/ΔV, and Efnb33FΔV/3FΔV mutants at P12. Scale bar: 20 pA (vertical) × 1s (horizontal). (b, c) Quantification of mEPSC frequency (b) and amplitude (c) for CA1 pyramidal neurons from the different Efnb3 mutants (n = 15). Mean ± s.e.m. * P < 0.05; *** P< 0.001.

We next studied dendritic branching and synaptogenesis in cultures of primary hippocampal neurons from WT, Efnb3−/−, and Efnb3ΔV/ΔV mutants collected at birth (P0). Following 8 days growth in vitro, the cultures were transfected with a membrane-anchored farnesylated EGFP (f-EGFP) marker and then analyzed four days later with antibodies against GFP and synapsin, a presynaptic marker, to visualize dendrites and synapses. The data showed that neurons from Efnb3−/− hippocampi had more primary dendritic processes (8.3 ± 1.3) and less spines and synapsin-positive synapses on spines compared to the WT neurons which exhibited fewer primary dendrites (4.8 ± 0.8) and greater density of spines and synapses (Supplementary Fig. 10a,b and Fig. 5a,b). Similarly, neurons from Efnb3ΔV/ΔV cultures also exhibited more primary dendrites (9.4 ± 0.7) and fewer spines and synapses on both spines and shafts (Supplementary Fig. 10a,b and Fig. 5a,b). We further transfected eB2, eB3 or eB3ΔV into cultured Efnb3−/− hippocampal neurons to see if the role of eB3 is rescued. The data showed that both eB2 and eB3 expression were able to compensate Efnb3 deficit whereas eB3-ΔV mutant failed to rescue (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Electrophysiological recordings further revealed a reduced frequency of mEPSCs in Efnb3 −/− and Efnb3ΔV/ΔV neuron cultures compared to WT littermates (Fig. 5c), which is consistent with the results obtained from acute hippocampal slices and indicates fewer functional synapses form in the absence of the eB3 PDZ binding motif.

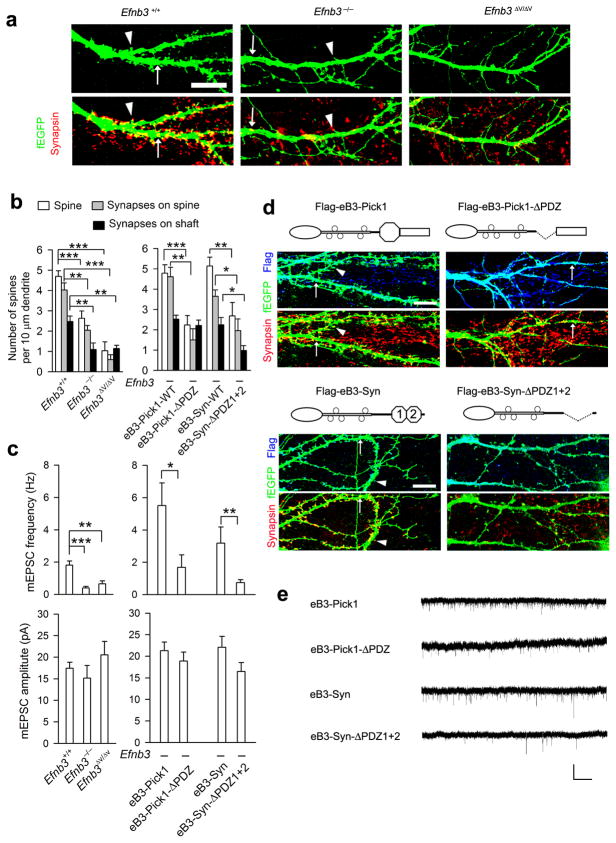

Figure 5. Pick1 and syntenin mediate ephrin-B3 reverse signaling through PDZ binding to control spine/synapse formation and synaptic function.

(a) Spine and synapse formation were indicated with a transfected f-EGFP reporter and presynaptic marker synapsin in 12d cultured hippocampal neurons from WT, Efnb3−/−, and Efnb3ΔV/ΔV mice. Arrowhead and arrow indicate synapse on spine and synapse on shaft, respectively. Scale bar: 10 μm. (b) The density of spines and synapses on spines (arrowhead)/shafts (arrow) were quantified. n = 10. (c) mEPSCs were recorded in 12–14 day cultured neurons from Efnb3 mutants and WT (left), and in Efnb3−/− hippocampal neurons that were infected with lentivirus packaged eB3-Pick1 or eB3-syntenin (Syn) expression vectors. Quantification of mEPSC frequency (upper) and amplitude (lower) is shown. n =15–20. Mean ± s.e.m. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 in b and c. (d) Expression of Flag-tagged WT eB3-Pick1 or eB3-syntenin (Syn) chimeric fusion proteins (left panels) in transfected Efnb3−/− neurons rescues spine and synapse formation as visualized with f-EGFP and synapsin in chimeric protein expressing neurons labeled with anti-Flag antibodies (upper panels). Expression of the eB3-Pick1-ΔPDZ or eB3-Syn-ΔPDZ1+2 fusion proteins deleted for the respective PDZ domains (right panels) had little if any effect on spine and synapse formation in Efnb3−/− neurons. Scale bar: 10 μm. (e) Example of mEPSC recorded in Efnb3−/− neurons expressing eB3-Pick1 or eB3-syntenin (Syn) fusion proteins and their PDZ deleted mutant forms. Scale bar: 40 pA (vertical) × 2 s (horizontal).

Pick1/syntenin transduces ephrin-B3 signals in dendrites

Among the downstream PDZ domain-containing molecules that may participate in ephrin-B reverse signaling, Pick1 and syntenin are expressed in the developing hippocampus (Supplementary Fig. 11), are localized to dendritic spines and synapses 33–35, and associate with ephrin-B proteins 36–38. Pick1 is a homo-oligomerizing BAR domain protein that contains a single N-terminal PDZ domain that binds many target proteins 39. Syntenin has two PDZ domains with different binding affinity to ephrin-B and other membrane associated molecules such as syndecan, glutamate receptors and neurofascin 40, and has been implicated to participate with eB1 and eB2, but not eB3, in presynaptic development 15. To determine if Pick1 or syntenin is involved in postsynaptic development of dendrites and synapses, we overexpressed in primary hippocampal neurons the full-length versions of Pick1 or syntenin and various mutants, including the isolated Pick1 PDZ domain (Pick1-PDZ), and PDZ deletion mutants Pick1-ΔPDZ, Syn-ΔPDZ1, and Syn-ΔPDZ2, along with f-EGFP to label the transfected cells. Dendritic branches, spine density, and synapse formation were visualized with antibodies against GFP and synapsin. The data showed overexpressing WT syntenin in Efnb3 −/− neurons reduced the number of primary dendrites and increased density of spines and synapses while overexpressing Pick1 did not (Supplementary Fig. 12 and 13), suggesting that eB3 is essential for Pick1 but not syntenin mediated function in neurons. In WT neurons, overexpressing WT syntenin but not its mutants reduced the number of primary dendrites compared to untransfected control neurons, while no change in number of primary dendrites was observed for any of the Pick1 expressing neurons (Supplementary Fig. 12). Moreover, expression of either Pick1-PDZ or syntenin mutants Syn-ΔPDZ1/Syn-ΔPDZ2, which have one PDZ domain left, reduced the density of spines and synapses (Supplementary Fig. 13). Consistent with this observation, electrophysiological recordings in neuron cultures determined that expression of Pick1-PDZ or syntenin mutants reduced the frequency of mEPSCs in WT neurons, while WT Pick1 and syntenin led to an increase (Supplementary Fig. 14). This data suggests roles for Pick1 and syntenin and their PDZ domains in regulating the number of functional synapses.

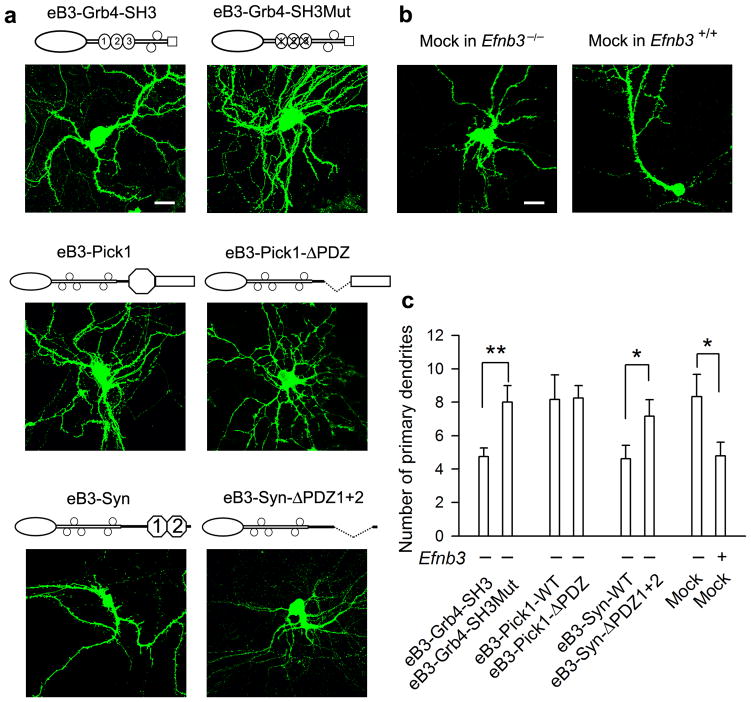

To further determine the sufficiency of Pick1 and syntenin in ephrin-B signaling, we expressed in Efnb3−/− primary hippocampal neurons Flag-tagged eB3-Pick1 and eB3-syntenin chimeric fusion proteins, in which the eB3 C-terminal valine residue was deleted and replaced with either full length Pick1 or syntenin (Flag-eB3-Pick1 or Flag-eB3-Syn) or their ΔPDZ mutants (Flag-eB3-Pick1-ΔPDZ or Flag-eB3-Syn-ΔPDZ1+2) (see cartoons in Fig. 5d). The idea behind these constructs is to bypass the requirement for PDZ mediated protein-protein associations of Pick1 or syntenin with eB3 and to exclude other possible PDZ associations by covalently linking Pick1 or syntenin directly to the eB3 C-terminus but still keeping their ability to interact with downstream Pick1/syntenin binding proteins. For the control fusion proteins Flag-eB3-Pick1-ΔPDZ or Flag-eB3-Syn-ΔPDZ1+2, lack of PDZ domains will disrupt their binding to other proteins. The expression vectors were co-transfected with f-EGFP into 8 day cultured primary hippocampal neurons from Efnb3−/− pups collected at P0 and scored 4 days later using IF with anti-GFP, anti-synapsin and anti-Flag antibodies. The data showed that Efnb3−/− neurons expressing either eB3-Pick1 or eB3-Syn, which is indicated by anti-Flag IF (Fig. 5d upper panels), exhibited significantly higher density of spines and spine synapse than the neurons expressing their PDZ deleted forms (Fig. 5b, d) which appeared like the control untransfected Efnb3−/− neurons. Interestingly, eB3-Syn expressing neurons also showed reduced primary dendritic branches (Fig. 6a, c), which were similar to that of WT neurons (Fig. 6b, c), while eB3-Pick1 expressing neurons remained unchanged (Fig. 6a, c). This is in contrast to the effects of gain-of-function eB3-Grb4-SH3 chimeric fusion proteins for axon pruning in transfected neurons 14, and which presented here with a reduction in primary dendritic branches but same amount of spines and synapses compared to loss-of-function eB3-Grb4-SH3Mut fusion proteins with inactivated SH3 domains (Fig. 6a, c). Electrophysiological recordings further confirmed that both eB3-Pick1 and eB3-Syn expressing neurons exhibited remarkably higher mEPSC frequency than those expressing the PDZ domain deleted mutants while no change in amplitude was observed (Fig. 5c, e). These results indicate that both eB3-Pick1 and eB3-Syn chimeric fusion proteins provide for a gain-of-function of eB3 to induce spine maturation and synapse formation in the absence of other PDZ protein binding to eB3. Consistent with this their PDZ domain deleted forms act as loss-of-function.

Figure 6. Grb4, Pick1 and syntenin mediated distinct reverse signaling to prune primary dendrites in cultured hippocampal neurons.

(a) Expression of eB3-Grb4-SH3 or eB3-syntenin (Syn) chimeric fusion proteins in transfected Efnb3−/− hippocampal neurons reduces primary dendrites as visualized with f-EGFP. Expression of eB3-Pick1 or its mutant eB3-Pick1-ΔPDZ or mutants of eB3-Grb4 or eB3-Syn fusion proteins had little if any effect on the number of primary dendrites in Efnb3−/− neurons. Scale bar: 10 μm. (b) Cultured hippocampal neurons at P12 from Efnb3−/− mice show more primary dendritic branches comparable to that from WT littermates as visualized with f-EGFP. Scale bar: 10 μm. (c) Quantitative analysis for number of the primary dendrites in neurons expressing different chimeric fusion proteins. Mean ± s.e.m. n =10–12. * P < 0.05; ** P< 0.01.

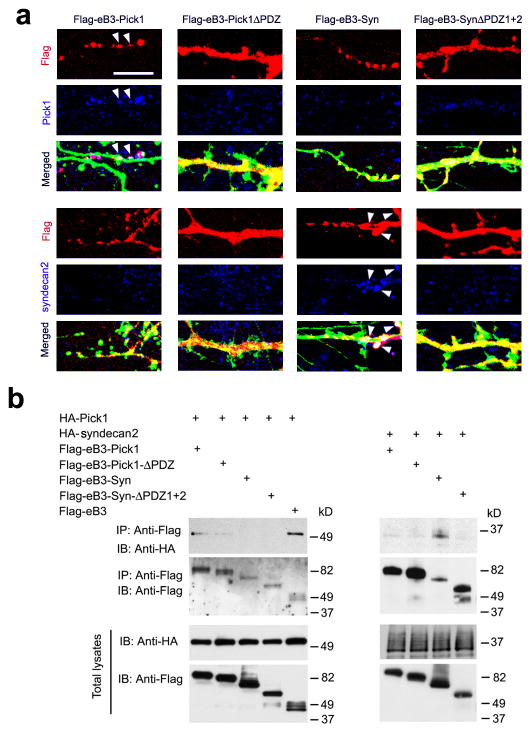

To further clarify how the various WT and PDZ deleted eB3-Pick1 and eB3-Syn fusion proteins result in gain-of function and loss-of-function effects, we tested whether these chimeric fusion proteins were able to form protein-protein complexes with syndecan2, a syntenin associated protein expressed in the hippocampus 36,41, or additional Pick1, which is thought to homo-oligomerize 39, using IF co-localization and co-immunoprecipitation in transfected cells (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 15). The data showed that the WT form eB3-Pick1 was able to recruit more Pick1 than the eB3-Pick1-ΔPDZ form did, but no obvious interaction of syndecan2 was found with either eB3-Pick1 fusion proteins. In contrast, the WT form eB3-Syn was able to interact with syndecan2 but not Pick1, while Syn-ΔPDZ1+2 bound to neither. These data suggests that while both Pick1 and syntenin are capable of mediating eB3 reverse signaling via PDZ dependent mechanism, these two proteins transduce ephrin-B signals via two distinct pathways involving different protein-protein interactions that either enable both dendrite pruning and spine maturation (syntenin) or only spine maturation (Pick1).

Figure 7. Association of eB3-Pick1 or eB3-Syn with downstream signaling molecules.

(a) Following EphB2-Fc treatment for 16 h in cultured hippocampal neurons to cluster the eB3 proteins to spots on the plasma membrane, WT Flag-eB3-Pick1 co-localized with Pick1 while WT Flag-eB3-syntenin (Syn) colocalized with syndecan-2 (SDC2), which is indicated by arrowheads. The PDZ domain deleted proteins showed highly diminished or no ability to form protein-protein interactions with Pick1 or syndecan-2. Scale bar: 5 μm. (b) In transfected Cos-1 cells, HA-Pick1 or HA-syndecan2 was co-immunoprecipitated with WT Flag-eB3-Pick1 or Flag-eB3-syntenin (Syn), respectively, but little if any was precipitated with the eB3-Pick1-ΔPDZ or eB3-Syn-ΔPDZ1+2 PDZ deleted counterparts. IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation. The presented bolts were cropped and the full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 15.

DISCUSSION

Ephrin-B mediates reverse signaling at postsynaptic structures

The current study is in contrast to the extensive studies of postsynaptic Eph receptors on dendritic morphogenesis 1,3,4 that invoke ephrin-Bs as presynaptic players in axons and nerve terminals 13–17, and indicates eB3 also functions as a postsynaptic receptor to transduce reverse signals required for both long-scale dendrite pruning and short-scale spine maturation. As interacting molecules EphB1 and EphB2, on the other hand, act as presynaptic ligands to stimulate eB3 reverse signals. Such a postsynaptic role for eB3 in the CA3-CA1 circuit is consistent with its intense expression in CA1 neurons initiated after the first postnatal week and coinciding with robust expression of EphB1 and EphB2 molecules in CA3 neurons 14.

The present study provides evidence that upon axon-dendrite contact followed by interaction with presynaptic EphB receptors, postsynaptic eB3 is able to recruit Grb4 and Pick1/syntenin through SH2 or PDZ binding motifs, respectively. These downstream molecules bridge eB3 with different cytoskeletal regulators, receptors, and ion channels by protein-protein interaction and altering either their subcellular targeting and/or surface expression 5,39,40. This provides a mechanism by which both dendrite pruning molecules and functional synaptic structure related molecules are recruited to the postsynaptic sites upon axon-dendrite contact at the earliest developmental stages. The dual function of postsynaptic eB3 is attributable to its ability to interact with three different downstream proteins, the SH2/SH3 adaptor Grb4 and two PDZ domain-containing proteins, syntenin and Pick1, which we hypothesize are able to recruit cytoskeletal regulators to prune exuberant dendritic processes and synaptic components needed to sculpt dendritic spines and form synapses.

Grb4, Pick1 and syntenin transduce distinct signals

Grb4 has been shown to couple eB3 to Dock180 and PAK to bring about guanine nucleotide exchange and signaling downstream of Rac and cdc42 (Ref. 14), which may be involved in regulation of dendrite growth and remodeling 42. Pick1 contains a PDZ domain in the N terminus and a BAR domain in the C terminus 39. The PDZ domain of Pick1 binds to a large number of membrane proteins including ephrin-Bs, while the BAR domain binds lipid molecules and may oligomerize with other BAR domains 39. Our results show that the PDZ domain also contributes to the oligomerization/dimerization of Pick1, which is also supported by evidence the PDZ domain enhances the BAR domain’s lipid binding 43. Therefore, both BAR and PDZ domains are crucial for the formation of Pick1 homodimer on the cell membrane to bridge eB3 with various postsynaptic associated molecules.

Interestingly, unlike Grb4 or Pick1 with sole function for either dendritic pruning or spine maturation, respectively, syntenin affects both pruning and spine maturation and both functions require its PDZ domains. Mechanistically, syntenin might interfere with actin dynamics by interacting with focal-adhesion kinase (FAK) 44 and by facilitating receptor subcellular trafficking such as syndecan, which is regulated by PIP2 and Arf family GTPase 45 and has been implicated to regulate dendritic filopodia and branching 46. Furthermore, syntenin interacts with adhesion molecules such as synCAM, neurofascin and syndecan, all of which contribute to synaptic structure 40. Thus, the dual function of syntenin in dendrite morphogenesis which relays its surprising variety and diversity of interacting partners 40 contributes to the eB3 reverse signals that mediate synaptic maturation and formation of neural circuits.

Presynaptic EphBs act as ligands

In addition to the role of eB3 at postsynapses, the present study also provides evidence that presynaptic EphB1 and EphB2 localized in CA3 axon terminals serve as ligands to mediate trans-synaptic signaling. Although the postsynaptic requirement of EphB forward signaling for spine maturation and synapse formation in CA3 neurons has been demonstrated previously 12, our data shows the specific CA3 expressed receptor EphB1 is also required and CA3/CA1 expressed EphB2 receptor intercellular domain is not required for spine maturation of developing CA1 pyramidal neurons. This data indicates the role of EphB for the development of dendrites and spines is as the presynaptic, CA3-expressed ligands to bind CA1-expressed eB3 and stimulate reverse signaling.

Our study does not rule out the possibility of a cis interaction of eB3 and EphB2 in CA1 neurons. EphB2 has been shown to interact with the NMDA receptor via its extracellular domain in adult animals which does not require the intracellular segment 9,11,47. However, for subsequent steps in postsynaptic specialization, the trans-synaptic binding with ephrin-Bs and the kinase activity of EphB are important 9,48. This scenario is in contrast to what we show here, in which ephrin-B molecules are specifically expressed in the postsynaptic compartment of CA1 neurons and the intracellular segment of EphB2 is not required for spine maturation. Therefore, the deficits in CA1 dendrites observed in EphB mutants are unlikely caused by interacting with EphB in cis manner, but are due to a ligand-like role of EphB receptors in presynaptic CA3 axons and nerve terminals.

Taken together, upon axon-dendrite contact, presynaptic EphB molecules bind postsynaptic eB3 which interacts with Grb4, Pick1 and syntenin to transduce distinct reverse signals into developing dendrites to control both long-scale branching elimination/pruning and short-scale spine maturation/synapse formation (Supplementary Fig. 16). Ephrin-B3 was also shown to regulate spine formation using in vitro cultured cortical neurons via the MAPK pathway 19 and has been implicated in promoting shaft synapse formation through GRIP 18. Therefore, further clarification of the mechanisms by which ephrin-B, Grb4, Pick1, syntenin, and other signaling pathways are coordinated upon axon-dendrite contact to regulate cytoskeletal elements should lead to an increased understanding of the complex dynamics of dendrite morphogenesis, spine maturation, and synaptic plasticity in the developing and adult brain.

METHODS

Mice and sample preparation

Efnb3−, Ephb33F, Ephb35F, Efnb3lacZ, Efnb2lacZ, Efnb26FΔV, EphB1−/−, and EphB2−/− knockout and knockin mutant mice and genotyping methods have been described 6,14,27–29,49. Mice were crossed with the Thy1-GFP M transgenic mouse line 26. Consecutive backcrosses to the CD1 strain were performed to move the mutations to CD1 background. Mice were anesthetized (ketamine, 450 mg/kg), perfused transcardially with 0.1 M PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer. The brains were then removed, postfixed and sectioned at 50 μM using a vibratome. All experiments involving mice were carried out in accordance with the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Animals under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol and Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care approved Facility at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

X-gal staining, immunofluorescence and Golgi stain

To detect the β-gal expression by X-gal stain, mouse brain sections were processed as described 6. For immunofluorescence, vibratome sections were incubated with a blue fluorescence dye NeuroTrace 640/660 (Molecular Probes) for visualization. For Golgi stain, freshly dissected P12, P20 mouse brains were incubated in Golgi solution containing 1.25% potassium dichromate, 1.25% HgCl and 1% KCl in distilled water for 12 days. After incubation mouse brains were embedded and sectioned at 100μM using a vibratome and mounted on 3% gelatin-coated slides. For staining, the slides were washed with 20 % ammonium hydroxide and fixed in Kodak fixer solution.

Generation of Efnb3 mutant mice

The Efnb3 targeting vectors used incorporated loxP site-specific recombination sequences and were designed to generate two-step mutations as described previously 14 from a single gene targeting event in murine embryonic stem cells (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7). The initial insertions, which are called Efnb3neo, eB3neoΔV or eB3neo3FΔV, inserts into the Efnb3 fourth intron (171 bp upstream of the splice acceptor for the fifth exon) a PGK promoter driven neomycin resistance (neo) cassette that was flanked with loxP sequences. As designed, this replaces WT Efnb3 exon 5 encoding amino acids 205–340 including the cytoplasmic domain with WT, or engineered mutations ΔV or 3FΔV in which tyrosine codons at positions 311, 318, 323 (for 3FΔV) are changed to phenylalanines and/or valine codon at position 340 is deleted (for 3FΔV or ΔV). Chimeric mice were made from two lines of each mutation and germline transmission was obtained, leading to recovery of the initial targeted Efnb3neo, Efnb3neoΔV or Efnb3neo3FΔV lines. Because this strategy was based on our initial gene targeting of Efnb3 that showed insertion of a neo cassette into the fourth intron disrupts the gene and leads to the null phenotype of a hopping locomotion 27, the initial, Efnb3neoΔV or Efnb3neo3FΔV lines when made homozygous also resulted in a loss-of-function hopping phenotype as expected. These mice were then crossed to a ubiquitous CAGG-CreERT2M driver following with a tamoxifen administration (for Efnb3neo) or a germline Cre-expressing transgenic mouse (for Efnb3neoΔV or Efnb3neo3FΔV) to remove the loxP-flanked neo cassette and convert the locus to restore eB3 expression conditionally or to generate the intended Efnb3 mutants alleles that express the intended eB3 protein with select point mutations in the cytoplasmic domain. Animals were genotyped by Southern blot with the probes as indicated and PCR with forward primer TCCCATCTTCAGGTCCCCGAG and reverse primer TGGAAATCCAGGTGTCCGGCC for wild-type (380 bp), and forward primer GGTGCTTCTGCGAGTGG and reverse primer GCATACATTATACGAAGTTATATTAAGGG for mutant (530 bp) (Supplementary Fig. 7b). The 3F and 5F mutations in the Efnb3 exon 5 were further confirmed by sequencing PCR amplified products from Efnb3neoΔV and Efnb3neo3FΔV mice. The expression level of Efnb3 and Efnb2 mRNA in hippocampus from Efnb3 mutants were further examined by using quantitative real-time PCR with forward primer GTGCCAGACAAG AGCCATGAA and reverse primer GGTGCTAGAACCTGGATTTGG for Efnb2, and forward primer cgtagtCCCCTTCTGCCCTCAC and reverse primer AGATGTTCGGAGGGCTCTGG for Efnb3.

Biochemistry analysis

Brain tissues from WT and Efnb3 mutants were dissected and homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 1% Triton-100, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaF, 1% BSA, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor mixture; Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Following immunoprecipitation with Goat anti-Pick1 (Novus) over night and incubation with protein G beads for 2 h at 4 °C, bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and then immunoblotted with Rabbit-anti-eB3 (Invitrogen). For biotinalytion of cell surface proteins, primary neurons dissected from P0 hippocampus were cultured for 12 days and surface proteins were isolated by using Biotinylation Kits (Pierce).

For immunopreciptation in Cos-1 cells, Flag-eB3-Pick1, Flag-eB3-Syn and their mutant form were transfected to assay protein-protein interaction with HA-Pick1 or HA-syndecan-2. The procedure was performed as described previously 14.

DNA constructs

To express various eB3 proteins by transfection and infection, Flag tagged WT and mutant Efnb3 coding sequences were generated from pEXPRmELF3 (provided by Andrew Bergemann) and ligated in the EcoR1 and Nhe1sites of pFUGW vector. Various syntenin and Pick1 coding regions were produced by PCR and ligated into pFUGW vector. Constructs were transfected directly into neurons or packaged into lentivirus to infect cells.

Primary neuron culture, transfection, and lentiviral infection

Hippocampal neurons from dissected P0 hippocampi were grown as described previously 14. Lentiviruses were produced by transfecting HEK293 cells with pFUGW vectors and two helper plasmids (pVSVg and pCMVΔ8.9). Viruses were harvested 48 hr after transfection by collecting the medium from transfected cells. Neurons were infected with 0.2–0.5 ml conditioned HEK293 cell medium for each 24 well of high-density neurons at 5 and 8 DIV culture, and the medium was exchanged to normal growth medium 1 day later, then kept until 12 DIV-14 DIV electrophysiological analyses. For immunocytochemistry, the neurons were transfected by using polyethylenimine.

Electrophysiology

Mutant mice and their wild-type littermates aged P12 were anaesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and decapitated. Brains were quickly dissected in 5% CO2 and 95% O2 ice-cold ACSF (119 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 26.2 mM NaHCO3, 11 mM glucose, 2 mM CaCl2 and 2 mM MgCl2) after bubbling with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Brains were vibratome-sectioned in the same solution at 400 μm and transferred to a chamber with bubbling with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 30 min and then maintained at room temperature (22–25 °C). Neurons were targeted for whole-cell patch-clamp recording with borosilicate glass electrodes having a resistance of 5–8 MΩ. The electrode internal solution was composed of 125 mM potassium gluconate, 10 mM HEPES, 2.6 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1.3 mM NaCl, 0.07 mM CaCl2, 15 mM Sucrose, 17.3 mM Tris phosphocreatine, 0.36 mM Na-GTP and 5 mM Mg-ATP. CA1 pyramidal neurons were selected from the dorsomedial hippocampus. For mEPSC recording, tetrodotoxin (1 μM) and picrotoxin (100 μM) were included in the external solution. Cells were held at −70 mV. Miniature responses were acquired with a Multiclamp 700B at 10 kHz. Prior to mEPSC detection and analysis, current traces were low-pass filtered at 5 kHz. Events having amplitude of 2× root mean square noise were detected using Mini Analysis (Synaptosoft).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings on cultured neurons were made at room temperature from 12–14 DIV cultured neurons, with 4–6 MΩ patch pipettes filled with an internal solution containing 120 mM CsCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 0.3 mM Na3-GTP, 4 mM Na2-ATP ( pH 7.4). Cultures were continuously superfused with external solution containing of 140 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2,1 μM tetrodotoxin and 100 μM picrotoxin (pH 7.4). Miniature responses were acquired with PCLAMP 10 software (Molecular Devices) at 10 kHz.

Quantification of dendrites, spine density and synaptic puncta

Confocal images of Thy1-GFP expressed neurons from P9–P20 mice were obtained with sequential acquisition settings at the maximal resolution of the microscope (1024 × 1024 pixels). Each image was a Z-series of 7 images each averaged 2 times. The resulting z-stack was flatted into a single image using maximum projection. A total of 20 cells for WT, Efnb3 mutants; four animals were used per genotype. Quantification of the number of primary dendrites (defined as dendrites longer than 21 μm emanating directly from the soma) and total dendrites (defined as the amount of all dendritic branches) was done on images acquired with 25× objective, in which a circle was drawn around the cell body and the number of dendrites crossing each circle (primary dendrites) and the total branches were manually counted. Quantitative analysis for spines was performed by using NeuronStudio 50 and ImageJ in images acquired with 100× objective. The number of spines with length of 0.5–2.0 μm and wide head diameter (> 0.2 μm) were accounted and divided by the total length of GFP labeled dendritic branches. For quantitative analysis for cumulative plot of spine length and head width, the protrusions with length 0.2–3.0 μm and Max width 3 μm were counted. For assessment of synapses on spine or shaft in cultured neurons, only synapsin puncta with directly adjacent GFP labeled spine buttons or shafts were scored as colocalized synapses on spine. Acquisition of the images as well as morphometric quantification was performed under “blinded” conditions.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical differences were determined by Student’s t test for two-group comparisons or ANOVA followed by Tukey test for multiple comparisons among more than two groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joshua Sanes for Thy1-GFP-M transgenic mice, George Chenaux for Efnb26FΔV mice, Hongkui Zeng and Jane E. Johnson for providing CAGG-tdTomato transgenic mice, Andrew McMahon and Richard Lu for providing CAGG-Cre-ER™ transgenic mice, Iryna M. Ethell for HA-syndecan-2 plasmid, Ilya Bezprozvanny for electrophysiological recording setup for studies of cultured cells, Benjamin Miller and Ankur Patel for assistance on electrophysiology, and Frances Prince for genotyping. This research was supported by the NIH (R01 MH66332) to MH.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contribution

N.-J.X. generated Ephb33F, Ephb35F, Efnb3ΔV and Efnb33FΔV knockin mice. N.-J.X. and S.S. performed the experiments. J.G. supervised the electrophysiological recording in brain slides. N.-J.X. and M.H. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ethell IM, Pasquale EB. Molecular mechanisms of dendritic spine development and remodeling. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:161–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parrish JZ, Emoto K, Kim MD, Jan YN. Mechanisms that regulate establishment, maintenance, and remodeling of dendritic fields. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:399–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein R. Bidirectional modulation of synaptic functions by Eph/ephrin signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:15–20. doi: 10.1038/nn.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai KO, Ip NY. Synapse development and plasticity: roles of ephrin/Eph receptor signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. Ephrins in reverse, park and drive. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henkemeyer M, et al. Nuk controls pathfinding of commissural axons in the mammalian central nervous system. Cell. 1996;86:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland SJ, et al. Bidirectional signalling through the EPH-family receptor Nuk and its transmembrane ligands. Nature. 1996;383:722–725. doi: 10.1038/383722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalva MB, et al. EphB receptors interact with NMDA receptors and regulate excitatory synapse formation. Cell. 2000;103:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ethell IM, et al. EphB/syndecan-2 signaling in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Neuron. 2001;31:1001–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunwald IC, et al. Kinase-independent requirement of EphB2 receptors in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2001;32:1027–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00550-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henkemeyer M, Itkis OS, Ngo M, Hickmott PW, Ethell IM. Multiple EphB receptor tyrosine kinases shape dendritic spines in the hippocampus. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1313–1326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush JO, Soriano P. Ephrin-B1 regulates axon guidance by reverse signaling through a PDZ-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1586–1599. doi: 10.1101/gad.1807209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu NJ, Henkemeyer M. Ephrin-B3 reverse signaling through Grb4 and cytoskeletal regulators mediates axon pruning. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:268–276. doi: 10.1038/nn.2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClelland AC, Sheffler-Collins SI, Kayser MS, Dalva MB. Ephrin-B1 and ephrin-B2 mediate EphB-dependent presynaptic development via syntenin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20487–20492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811862106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Contractor A, et al. Trans-synaptic Eph receptor-ephrin signaling in hippocampal mossy fiber LTP. Science. 2002;296:1864–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.1069081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim BK, Matsuda N, Poo MM. Ephrin-B reverse signaling promotes structural and functional synaptic maturation in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:160–169. doi: 10.1038/nn2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoto J, et al. Postsynaptic ephrinB3 promotes shaft glutamatergic synapse formation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7508–7519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0705-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClelland AC, Hruska M, Coenen AJ, Henkemeyer M, Dalva MB. Trans-synaptic EphB2-ephrin-B3 interaction regulates excitatory synapse density by inhibition of postsynaptic MAPK signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8830–8835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910644107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segura I, Essmann CL, Weinges S, Acker-Palmer A. Grb4 and GIT1 transduce ephrinB reverse signals modulating spine morphogenesis and synapse formation. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:301–310. doi: 10.1038/nn1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antion MD, Christie LA, Bond AM, Dalva MB, Contractor A. Ephrin-B3 regulates glutamate receptor signaling at hippocampal synapses. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;2010:30. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouzioukh F, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation sites in ephrinB2 are required for hippocampal long-term potentiation but not long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11279–11288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3393-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Essmann CL, et al. Serine phosphorylation of ephrinB2 regulates trafficking of synaptic AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1035–1043. doi: 10.1038/nn.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grunwald IC, et al. Hippocampal plasticity requires postsynaptic ephrinBs. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/nn1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodenas-Ruano A, Perez-Pinzon MA, Green EJ, Henkemeyer M, Liebl DJ. Distinct roles for ephrinB3 in the formation and function of hippocampal synapses. Dev Biol. 2006;292:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng G, et al. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron. 2000;28:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokoyama N, et al. Forward signaling mediated by ephrin-B3 prevents contralateral corticospinal axons from recrossing the spinal cord midline. Neuron. 2001;29:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dravis C, et al. Bidirectional signaling mediated by ephrin-B2 and EphB2 controls urorectal development. Dev Biol. 2004;271:272–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thakar S, Chenaux G, Henkemeyer M. Critical roles for EphB and ephrin-B bidirectional signaling in retinocollicular mapping. Nat Commun. 2011;2 :431. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2002;244:305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madisen L, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2009;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. The SH2/SH3 adaptor Grb4 transduces B-ephrin reverse signals. Nature. 2001;413:174–179. doi: 10.1038/35093123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Citri A, et al. Calcium binding to PICK1 is essential for the intracellular retention of AMPA receptors underlying long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16437–16452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4478-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirbec H, Martin S, Henley JM. Syntenin is involved in the developmental regulation of neuronal membrane architecture. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:737–746. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura Y, et al. PICK1 inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex controls dendritic spine size and synaptic plasticity. Embo J. 2011;30:719–730. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grootjans JJ, Reekmans G, Ceulemans H, David G. Syntenin-syndecan binding requires syndecan-synteny and the co-operation of both PDZ domains of syntenin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19933–19941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002459200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin D, Gish GD, Songyang Z, Pawson T. The carboxyl terminus of B class ephrins constitutes a PDZ domain binding motif. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3726–3733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres R, et al. PDZ proteins bind, cluster, and synaptically colocalize with Eph receptors and their ephrin ligands. Neuron. 1998;21:1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu J, Xia J. Structure and function of PICK1. Neurosignals. 2006;15:190–201. doi: 10.1159/000098482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beekman JM, Coffer PJ. The ins and outs of syntenin, a multifunctional intracellular adaptor protein. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1349–1355. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ethell IM, Yamaguchi Y. Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan-2 induces the maturation of dendritic spines in rat hippocampal neurons. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:575–586. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Threadgill R, Bobb K, Ghosh A. Regulation of dendritic growth and remodeling by Rho, Rac, and Cdc42. Neuron. 1997;19:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80376-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin W, et al. Lipid binding regulates synaptic targeting of PICK1, AMPA receptor trafficking, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2380–2390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3503-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boukerche H, et al. mda-9/Syntenin: a positive regulator of melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10901–10911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zimmermann P, et al. Syndecan recycling [corrected] is controlled by syntenin-PIP2 interaction and Arf6. Dev Cell. 2005;9:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin YL, Lei YT, Hong CJ, Hsueh YP. Syndecan-2 induces filopodia and dendritic spine formation via the neurofibromin-PKA-Ena/VASP pathway. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:829–841. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henderson JT, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase EphB2 regulates NMDA-dependent synaptic function. Neuron. 2001;32:1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takasu MA, Dalva MB, Zigmond RE, Greenberg ME. Modulation of NMDA receptor-dependent calcium influx and gene expression through EphB receptors. Science. 2002;295:491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1065983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams SE, et al. Ephrin-B2 and EphB1 mediate retinal axon divergence at the optic chiasm. Neuron. 2003;39:919–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez A, Ehlenberger DB, Dickstein DL, Hof PR, Wearne SL. Automated three-dimensional detection and shape classification of dendritic spines from fluorescence microscopy images. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.