Abstract

Background. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of premature mortality in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). We examined peripheral augmentation index (AIx) as a measure of systemic vascular function and circulating markers of vascular inflammation in patients with ADPKD.

Methods. Fifty-two ADPKD patients with hypertension and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, 50 ADPKD patients with hypertension and eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, 42 normotensive ADPKD patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 51 normotensive healthy controls were enrolled in this study. AIx was measured from peripheral artery tone recordings using finger plethysmography. Serum levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, P-selectin, E-selectin, soluble Fas (sFas) and Fas ligand (FasL) were measured as markers of vascular inflammation.

Results. AIx was higher in all three patient groups with ADPKD compared to healthy controls (P < 0.05). AIx was similar between the normotensive ADPKD patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and hypertensive ADPKD patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (P > 0.05). ICAM, P-selectin, E-selectin and sFas were higher and FasL lower in all ADPKD groups compared to controls (P < 0.05). ICAM, P-selectin and E-selectin were similar between the normotensive ADPKD patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and hypertensive ADPKD patients with eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (P > 0.05). According to multiple regression analysis, predictors of AIx in ADPKD included age, height, heart rate and mean arterial pressure (P < 0.05). Vascular inflammatory markers were not predictors of AIx in ADPKD.

Conclusions. Systemic vascular dysfunction, manifesting as an increase in AIx and vascular inflammation is evident in young normotensive ADPKD patients with preserved renal function. Vascular inflammation is not associated with elevated AIx in ADPKD.

Keywords: hypertension, inflammation, kidney disease, vascular function

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of premature mortality in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), with >80% of deaths attributable to coronary artery disease [1]. Approximately 70% of patients with ADPKD have hypertension, which often manifests before and compounds subsequent renal dysfunction [2]. Recent evidence has implicated systemic vascular dysfunction and vascular inflammation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic CVD [3, 4], hypertension [5, 6] and renal demise [7–9] in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Moreover, vascular dysfunction and inflammation are associated with numerous cardiovascular morbidities and mortality in several clinical cohorts, including patients with CKD [10, 11]. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors do not fully explain CVD burden in CKD. Thus, measures of vascular function and vascular inflammation may offer novel insight into residual cardiovascular risk in patients with kidney disease.

Augmentation index (AIx) is a measure of systemic vascular function and ventricular–vascular coupling [12, 13]. In patients with CKD, elevated AIx is associated with progression to end-stage renal disease [7, 8]. Elevated AIx is also associated with numerous cardiovascular morbidities of polycystic kidney disease (PKD) pathology including coronary artery disease [3, 14], microalbuminuria [15], left ventricle (LV) hypertrophy [16, 17], cardiovascular events [14] and mortality [10]. Thus, AIx may be a clinically viable measure of CVD risk in ADPKD.

Patients with ADPKD have elevated AIx [18]. The mechanisms that contribute to elevated AIx in ADPKD remain unknown but may be related to inflammatory state. There is a strong link between systemic vascular dysfunction and inflammation [19, 20] and patients with ADPKD have an activated pro-inflammatory phenotype [21]. The relationship between AIx and vascular inflammation in ADPKD remains unexplored.

This is an ancillary study to the Halt Progression in PKD (HALT-PKD) Trial [22]. The overall purpose of the current cross-sectional study is to examine systemic vascular function (i.e. AIx) in patients with ADPKD after carefully characterizing hypertensive, inflammatory and renal state (strong determinants and confounders of vascular function). A secondary purpose is to examine traditional correlates (e.g. CVD risk factors) and non-traditional correlates (e.g. vascular inflammatory markers) of elevated AIx in ADPKD in an attempt to gain insight into underlying mechanism governing systemic vascular modulation in ADPKD. We hypothesized that patients with ADPKD would have higher AIx and this would be associated with elevated vascular inflammatory markers.

Materials and methods

Participants for this study consisted of 52 ADPKD patients with hypertension [systolic blood pressure (SBP) > 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) > 90 mm Hg] and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, 50 ADPKD patients with hypertension and eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, 42 normotensive ADPKD patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 51 normotensive healthy controls with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Major exclusion criteria for this study consisted of renal vascular disease, diabetes mellitus and history of severe heart failure. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated from serum creatinine using the 4-variable MDRD equation [23]. All patients gave written informed consent and this study was approved by the institutional review board at Tufts Medical Center.

Study design for HALT-PKD has previously been described in detail [22]. Of the 102 hypertensive patients recruited for this study, 78 patients underwent a 2-week medication washout (as part of the HALT-PKD study design) prior to hemodynamic, vascular and inflammatory appraisal. During this time, blood pressure (BP) was controlled in hypertensive patients with labetalol or clonidine. Non-HALT-PKD hypertensive patients (7 with eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73m2 and 17 with eGFR 25–60 mL/min/1.73m2 not included in HALT-PKD due to age and eGFR restrictions or inability to tolerate study medications) did not undergo this washout. All patients withheld antihypertensive medications for a minimum of 12 h prior to testing. Subjects were instructed to fast overnight and refrain from caffeine or alcohol intake and smoking on the day of testing.

Blood pressure

BP was assessed by a trained nurse using an automated device (Dinamap DPC120X-EN) following standard guidelines. Measurements were made with patients in a seated position following 5–10 min of quiet rest and the mean of three measures used for average resting BP.

Finger pulse wave amplitude

With patients in the supine position, beat-by-beat pulse wave amplitude (PWA) was captured using finger plethysmography (Itamar Medical Ltd, Caesarea, Israel) as previously described in detail by our group [24, 25]. AIx was calculated from PWA waveforms as the ratio of the difference between the early and late systolic peaks of the waveform relative to the early peak expressed as a percentage (P2 − P1/P1 * 100). The volume pulse waveform obtained from the finger has been shown to correlate well with pressure waveforms obtained from the finger, radial artery and carotid artery and changes in the digital volume pulse with perturbation have been shown to be very similar to changes in the pressure waveforms [26]. A computerized algorithm automatically identified peak volume and inflection points using a fourth-order derivative as previously described by Kelly et al. [27] and Takazawa et al. [28]. We have previously shown that AIx derived from this method is a sensitive measure of ventricular–vascular coupling [12].

Blood work

Fasting blood draws were obtained and stored at −70°C for subsequent batch analysis. Circulating markers of vascular inflammation measured from serum samples included: soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1, E-selectin, soluble Fas (sFas) and Fas ligand (FasL). Analysis of blood samples were performed in the general clinical research center’s laboratory using standard kits, in the Division of Nephrology at Tufts Medical Center.

Statistical analysis

All data are reported as means ± SDs. A priori significance was set at P < 0.05. Normality of distribution was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnof and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Group comparisons were made using analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc testing where appropriate. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables. If significant group differences in potential confounders existed, analysis of covariance was used to statistically remove the influence of these parameters of outcome variables of interest. Pearsons correlation coefficients were used to assess relationships between variables of interest. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed to examine predictors of AIx in our ADPKD cohort. Variables that demonstrated a univariate association (P = 0.1) with AIx were entered into the model and these included: age, gender, height, heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), P-selectin, E-selectin, sFas, total cholesterol, fasting glucose and eGFR. In order to further examine the association between age and AIx in patients with ADPKD, regression curve analysis was performed. The curve (linear, quadratic, cubic, logarithmic and power) that explained the greatest proportion of the variance in AIx was taken as the model of best fit.

Results

Patient descriptive characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients with ADPKD hypertension (HTN) eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 were older than other groups (P < 0.05). There were significantly more white patients in the ADPKD groups compared to healthy controls (P < 0.05). Healthy controls had significantly higher eGFR compared to all patient groups with ADPKD (P < 0.05). By design, there were also significant group differences in eGFR between ADPKD groups (Table 1, P < 0.05). Patients with ADPKD HTN eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 had higher body mass than patients with ADPKD eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 and healthy controls (P < 0.05). Patients with ADPKD HTN eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 had significantly lower HR than healthy controls and ADPKD eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 (P < 0.05). Both patient groups with ADPKD HTN had significantly higher SBP, DBP and MAP than healthy controls and normotensive ADPKD (P < 0.05). Antihypertensive medication use was also significantly different between groups with ADPKD patients taking more of these agents than healthy controls (Table 1, P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Patient descriptive and clinical characteristicsa

| Variable | Healthy control, n = 51 | ADPKD GFR ≥ 60, n = 42 | ADPKD HTN GFR ≥ 60, n = 50 | ADPKD HTN GFR < 60, n = 52 |

| Age, years | 37 ± 11 | 36 ± 10 | 39 ± 10 | 49 ± 8bcd |

| Male, % | 45 | 17b | 46c | 44c |

| White race, % | 61 | 83b | 96b | 92b |

| eGFR mL/min/1.73m2 | 102 ± 11 | 92 ± 21b | 89 ± 17b | 41 ± 13bcd |

| Height, meters | 1.71 ± 0.1 | 1.66 ± 0.08b | 1.73 ± 0.1c | 1.73 ± 0.1c |

| Body mass, kilograms | 72 ± 17 | 67 ± 13 | 78 ± 16 | 82 ± 18bc |

| HR, beats per minute | 66 ± 10 | 67 ± 12 | 61 ± 10c | 62 ± 10 |

| SBP, mmHg | 118 ± 15 | 121 ± 14 | 137 ± 15bc | 132 ± 18bc |

| DBP, mmHg | 70 ± 9 | 74 ± 9 | 81 ± 12bc | 78 ± 10b |

| PP, mmHg | 48 ± 12 | 47 ± 11 | 57 ± 11bc | 54 ± 15 |

| MAP, mmHg | 86 ± 10 | 90 ± 9 | 100 ± 11bc | 96 ± 11bc |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 186 ± 34 | 187 ± 30 | 196 ± 35 | 194 ± 41 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 85 ± 11 | 81 ± 8 | 77 ± 9b | 84 ± 9d |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 4 (8%) | 6 (14%) | 5 (10%) | 2 (4%) |

| Medication history | ||||

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | 9 (18%)b | 17 (33%)bc |

| Ca channel blocker, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (8%) | 11 (21%)bcd |

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 31 (62%)bc | 30 (58%)bc |

| AR blocker, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 10 (20%)bc | 15 (29%)bc |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 7 (14%)bc | 16 (31%)bcd |

| Statin, n (%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 10 (19%)bcd |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (13%)bcd |

Data are mean ± SD unless indicated.

Significantly different from healthy controls (P < 0.05).

Significantly different from ADPKD GFR > 60 (P < 0.05).

Significantly different than ADPKD HTN GFR > 60 (P < 0.05).

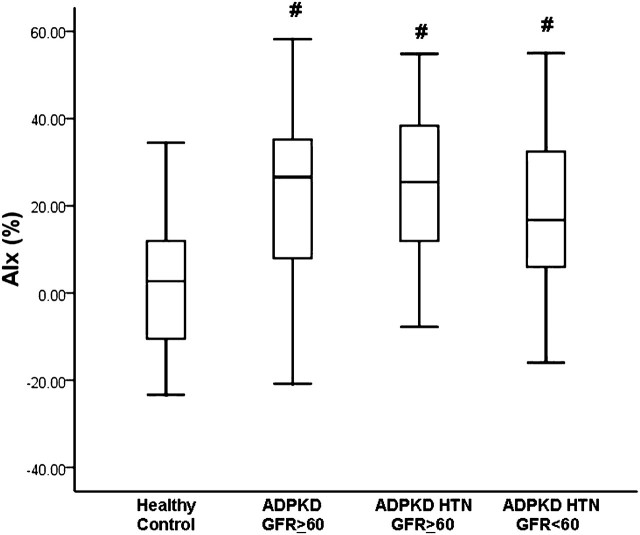

AIx was significantly higher in patients with ADPKD versus healthy controls (P < 0.05). As can be seen in Figure 1, AIx was similar between all ADPKD patient groups and this was higher than that seen in healthy controls (healthy control = 3 ± 17%, ADPKD eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 23 ± 19%, ADPKD HTN eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 25 ± 17%, ADPKD HTN eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 17 ± 19%; P < 0.05). Adjusting for age, height, HR, body mass, fasting glucose, gender and race had no effect on group differences in AIx (adjusted means: healthy control = 5%, ADPKD eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 16%, ADPKD HTN eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 24%, ADPKD HTN eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 20%; P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

AIx in healthy controls, patients with ADPKD and GFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2, patients with ADPKD HTN and GFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 and patients with ADPKD HTN and GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2. #Significantly different from healthy controls (P < 0.05).

Patients with ADPKD HTN eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 had significantly higher VCAM than patients with ADPKD eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 and patients with ADPKD HTN eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 (Table 2, P < 0.05). Patients with ADPKD had significantly higher sFas, ICAM, P-selectin and E-selectin than controls (Table 2, P < 0.05). Patients with ADPKD HTN eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 and ADPKD HTN eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 had significantly lower FasL than healthy controls and ADPKD eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 (Table 2, P < 0.05). Covarying for group differences in MAP and pulse pressure had no effect on aforementioned group differences in vascular inflammatory markers (data not shown).

Table 2.

| Variable | Healthy control, n = 51 | ADPKD GFR ≥60, n = 42 | ADPKD HTN GFR ≥60, n = 50 | ADPKD HTN GFR < 60, n = 52 |

| VCAM-1 ng/mL | 839 ± 264 | 705 ± 251c | 758 ± 250 | 912 ± 307de |

| ICAM-1, ng/mL | 194 ± 71 | 221 ± 67c | 241 ± 67c | 246 ± 82c |

| sFas, pg/mL | 6456 ± 1819 | 7695 ± 1729c | 8175 ± 1808c | 10510 ± 2207cde |

| FasL, pg/mL | 93 ± 37 | 89 ± 35 | 73 ± 35cd | 74 ± 43c |

| P-selectin, ng/mL | 19 ± 22 | 62 ± 22c | 53 ± 21cd | 61 ± 24c |

| E-selectin, ng/mL | 33 ± 18 | 43 ± 18c | 41 ± 17c | 44 ± 19c |

Data are mean ± SD.

Adjusted for age, body mass, gender, race and fasting glucose.

Significantly different from healthy control (P < 0.05).

Significantly different from ADPKD GFR ≥ 60 (P < 0.05).

Significantly different than ADPKD HTN GFR ≥ 60 (P < 0.05).

Adjusting for inflammatory markers (P-selectin, E-selectin and sFas) in addition to aforementioned confounders (age, height, HR, gender, race and fasting glucose) had no effect on group differences in AIx. Patients with ADPKD maintained higher AIx compared to controls (adjusted means: healthy control = 7%, ADPKD eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 17%, ADPKD HTN eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 22%, ADPKD HTN eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 16%; P < 0.05). Adjusting for MAP and pulse pressure in addition to aforementioned confounders also had no effect on group differences in AIx. Patients with ADPKD maintained higher AIx compared to controls (adjusted means: healthy control = 7%, ADPKD eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 18%, ADPKD HTN eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 21%, ADPKD HTN eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 = 18%; P < 0.05).

Univariate associations are presented in Table 3. According to stepwise multiple regression analysis, significant predictors of AIx included age (β = 0.39, P < 0.001; accounting for 14.8% of the variance), HR (β = −0.44, P < 0.001; accounting for an additional 8.9% of the variance), height (β = −0.35, P < 0.001; accounting for an additional 7.2% of the variance) and MAP (β = 0.24, P = 0.007; accounting for an additional 5.2% of the variance). Overall, the model accounted for 36.0% of the variance in AIx.

Table 3.

Intercorrelations for hemodynamic and vascular inflammatory parameters in ADPKD; PP, Pulse pressure

| Variable | AIx | GFR | MAP | PP | VCAM | ICAM | P-selectin | E-selectin | Fas |

| GFR | −0.29a | ||||||||

| MAP | 0.12 | −0.04 | |||||||

| PP | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.35a | ||||||

| VCAM | −0.02 | −0.40a | 0.06 | 0.21a | |||||

| ICAM | 0.08 | −0.19a | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.28a | ||||

| P-selectin | −0.13 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.03 | |||

| E-selectin | −0.21a | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.25a | −0.04 | ||

| Fas | 0.16 | −0.60a | 0.16 | 0.35a | 0.34a | 0.25a | −0.01 | 0.08 | |

| FasL | −0.05 | 0.15 | −0.14 | 0.15 | −0.15 | −0.12 | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.08 |

Significant association (P < 0.05).

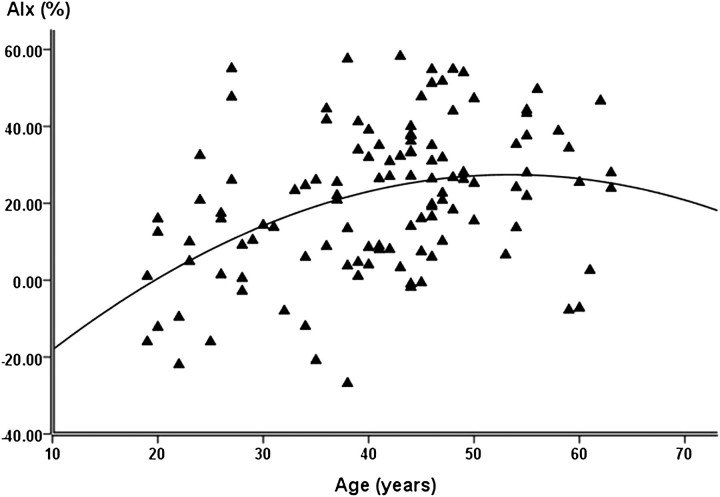

We examined the association of AIx with age in outpatients with ADPKD via regression curve analysis. In these patients, the association between AIx and age was best described by a quadratic curve (Figure 2, R2 = 15.3, P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Quadratic association between age and AIx in patients with ADPKD.

Discussion

In the present study, we characterized vascular function and vascular inflammation in a large cohort of patients with ADPKD after carefully appraising their hypertensive and renal status, potential detrimental modulators of vascular function and inflammation. Our findings suggest that elevated AIx and vascular inflammation are evident in young ADPKD patients without overt hypertension or renal dysfunction. Interestingly, elevated AIx in ADPKD is not associated with vascular inflammation. These findings suggest that elevated AIx in ADPKD may be independent of hypertensive, renal and inflammatory state.

We noted significantly higher AIx in patients with ADPKD compared to healthy controls and this is consistent with previous work by Borresen et al. [18] conducted in a smaller cohort of patients. AIx is a measure of systemic vascular function and ventricular–vascular coupling that is influenced by both the pump function of the heart (i.e. LV systolic and diastolic function) and properties of the systemic vasculature (forward pressure wave genesis, pressure from wave reflections, vascular compliance, vascular impedance, vascular resistance, vascular capacitance, arteriolar/vasomotor tone, vascular path length and vascular geometry) [12, 13]. Appropriate coupling between the LV and the systemic vasculature results in an optimal transfer of blood from the LV to the periphery (optimal cardiometabolic efficiency) without excessive changes in pressure pulsatility. Uncoupling owing to altered inoptropic/lusotropic/chronotropic cardiac function, increased arterial stiffness and forward pressure wave genesis and/or altered timing/increased magnitude of pressure from wave reflections increases AIx. Our study adds to previous findings by examining various traditional and non-traditional predictors of elevated AIx in ADPKD.

Predictors of AIx in our cohort included previously established ‘traditional’ factors such as height, HR, MAP and age [29, 30]. Height is presupposed as a surrogate for aortic path length. Shorter stature would equate with a reduced aortic path length, thus reducing overall travel time of forward and reflected pressure waves, increasing AIx [31]. HR affects AIx via altering the temporal association of forward and reflected waves. With a reduction in HR, systolic ejection duration is increased, allowing greater time for the reflected pressure wave to arrive during early systole, increasing AIx [32, 33]. Arterial stiffness varies non-linearly with distending pressure (i.e. MAP). With a rise in MAP, load bearing is transposed from more compliant elastin fibers to stiffer collagen fibers, passively increasing vascular stiffness and speeding the transit time of forward and reflected pressure waves, increasing AIx.

AIx increases with advancing age, however, this association is not linear. Previous studies note that there is an increase in AIx until ∼60–65 years of age, followed by a plateau and in some cases, a gradual decrease with further aging [34–36]. Our results support previous work by demonstrating that the increase in AIx with age in ADPKD is quadratic. The age-associated plateau in AIx occurred ∼10–15 years earlier in patients with ADPKD (∼50 years of age) suggesting possible premature vascular aging in this cohort.

Consistent with previous reports, we noted elevated plasma concentrations of vascular inflammatory markers (sFas, ICAM, P-selectin and E-selectin) in patients with ADPKD compared to healthy controls [21, 37, 38]. Interestingly, normotensive patients with ADPKD and preserved renal function had a heightened vascular inflammatory state as evidence by higher levels of ICAM, P-selectin, E-selectin and sFas compared to healthy controls. Thus, vascular inflammation is also seen in young patients with ADPKD independent of the presence of hypertension or renal dysfunction and this is a novel finding. We noted an association between select vascular inflammatory markers (VCAM, ICAM and sFas) and renal function. ADPKD patients with renal dysfunction had a trend toward higher vascular inflammation than ADPKD patients with preserved renal function. In pre-dialysis patients, vascular inflammatory markers ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 have been shown to be positively correlated with creatinine clearance [39]. Similarly, in patients with varying degrees of kidney function and types of glomerular disease, there is a positive correlation between sFas and level of creatinine clearance and proteinuria [40]. Thus, vascular inflammation has been implicated in the progressive loss of kidney function that characterizes ADPKD [41].

A strong link between vascular inflammation and vascular function has been suggested [19, 20]. Numerous studies have reported an association between AIx and inflammation in various clinical cohorts including patients with essential hypertension [42, 43] systemic vasculitis [44] and renal transplant recipients [45]. In the present study, none of the vascular inflammatory markers were significant predictors of AIx. Moreover, adjusting for vascular inflammatory markers had no effect on group differences in AIx. Our findings would suggest that vascular inflammation may not be a strong modulator of AIx in ADPKD. Thus, the pathogenesis of systemic vascular dysfunction and vascular inflammation may not be linked in this unique cohort.

Although there were group differences in age, height, HR and MAP, adjusting for these factors had no effect on group differences in AIx. Therefore, differences in traditional correlates of AIx cannot explain the higher values witnessed in ADPKD at this time. Non-traditional CVD-damaging factors inherent to the ADPKD phenotype may be responsible for elevations in AIx. Increased arterial stiffness increases pulse wave velocity, altering the timing and magnitude of forward and reflected pressure waves, increasing AIx [46]. However, previous studies have reported that patients with ADPKD do not have increased arterial stiffness [18, 47]. Thus, altered kinetics of forward and reflected pressure waves secondary to increased pulse wave velocity as an explanation for the increase AIx in ADPKD seems unlikely. There are numerous potential reflection sites that give rise to a single effective reflection site, contributing to the inflection point from which AIx is derived. One of the more prominent reflection sites is at the level of the renal arterial branches [48–50]. Moreover, the kidneys are a highly vascular organ with numerous potential smaller reflection sites. Renal cysts may mechanically compress the renal vasculature [51], physically altering renal reflection sites. Calcification of renal cysts is also a common occurrence in ADPKD [52] and this too may contribute to altered renal and systemic vascular properties [53]. Finally, normotensive patients with ADPKD and preserved renal function have higher renal vascular resistance [54]. Elevated renal vascular resistance combined with mechanical compression from calcified cysts may alter renal reflection coefficients, increasing the magnitude of reflected waves. AIx may thus be a sensitive measure of this early onset small vessel disease in ADPKD.

In conclusion, increases in AIx and vascular inflammation are evident in young normotensive ADPKD patients with preserved renal function and the level of vascular dysfunction is comparable to that seen in ADPKD patients with overt hypertension and renal dysfunction. Vascular inflammation exhibits a trend toward a graded relationship with level of kidney function while AIx demonstrates a threshold effect. These findings support the contention that systemic vascular dysfunction is a phenotypic expression in ADPKD. Further research is needed to examine the relative contributions of genetic aberrations, hypertension, inflammation, reduced renal function and vascular dysfunction to the increased CVD risk noted in ADPKD and whether intervening in aforementioned pathways can prevent progression and improve CVD outcomes in this patient population.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIDDK K23 DK67303; K24 DK078204; UL1 RR025752 from the National Center for Research Resources; Norman S. Coplon Extramural Grant from Satellite Healthcare and a grant from the Polycystic Kidney Foundation. The HALT-PKD study site at Tufts Medical Center is supported by a cooperative agreement from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases UO1DK62411, the NCRR GCRC RR000054 and UL1 RR025752. K.S.H was supported by funding from NIH T32 HL069770-06. We acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Gertrude (Peachy) Simon, Julie Driggs and Wendy Shinzawa.

Conflict of interest statement. Authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose. The results presented in this paper have not been previously published elsewhere, except in abstract form.

References

- 1.Perrone RD, Ruthazer R, Terrin NC. Survival after end-stage renal disease in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: contribution of extrarenal complications to mortality. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:777–784. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.27720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ecder T, Schrier RW. Hypertension in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: early occurrence and unique aspects. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:194–200. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V121194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covic A, Haydar AA, Bhamra-Ariza P, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity and arterial wave reflections predict the extent and severity of coronary artery disease in chronic kidney disease patients. J Nephrol. 2005;18:388–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filiopoulos V, Vlassopoulos D. Inflammatory syndrome in chronic kidney disease: pathogenesis and influence on outcomes. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2009;8:369–382. doi: 10.2174/1871528110908050369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell GF, Wang N, Palmisano JN, et al. Hemodynamic correlates of blood pressure across the adult age spectrum: noninvasive evaluation in the framingham heart study. Circulation. 2010;122:1379–1386. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Rifai N, et al. C-reactive protein and the risk of developing hypertension. JAMA. 2003;290:2945–2951. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taal MW, Sigrist MK, Fakis A, et al. Markers of arterial stiffness are risk factors for progression to end-stage renal disease among patients with chronic kidney disease stages 4 and 5. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;107:c177–c181. doi: 10.1159/000110678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takenaka T, Mimura T, Kanno Y, et al. Qualification of arterial stiffness as a risk factor to the progression of chronic kidney diseases. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:417–424. doi: 10.1159/000087605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation and progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68:237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.London GM, Blacher J, Pannier B, et al. Arterial wave reflections and survival in end-stage renal failure. Hypertension. 2001;38:434–438. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menon V, Greene T, Wang X, et al. C-reactive protein and albumin as predictors of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68:766–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heffernan KS, Patvardhan EA, Hession M, et al. Elevated augmentation index derived from peripheral arterial tonometry is associated with abnormal ventricular-vascular coupling. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2010;30:313–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2010.00943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heffernan KS, Sharman JE, Yoon ES, et al. Effect of increased preload on the synthesized aortic blood pressure waveform. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:484–490. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00196.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiura R, Kita T, Yamada K, et al. Radial augmentation index is related to cardiovascular risk in hemodialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial. 2008;12:157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2008.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsioufis C, Tzioumis C, Marinakis N, et al. Microalbuminuria is closely related to impaired arterial elasticity in untreated patients with essential hypertension. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;93:c106–c111. doi: 10.1159/000069546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.London GM, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, et al. Cardiac and arterial interactions in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 1996;50:600–608. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchais SJ, Guerin AP, Pannier BM, et al. Wave reflections and cardiac hypertrophy in chronic uremia. Influence of body size. Hypertension. 1993;22:876–883. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.6.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borresen ML, Wang D, Strandgaard S. Pulse wave reflection is amplified in normotensive patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease and normal renal function. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:240–246. doi: 10.1159/000101369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieb W, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, et al. Multimarker approach to evaluate correlates of vascular stiffness: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;119:37–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnabel R, Larson MG, Dupuis J, et al. Relations of inflammatory biomarkers and common genetic variants with arterial stiffness and wave reflection. Hypertension. 2008;51:1651–1657. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.105668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merta M, Tesar V, Zima T, et al. Cytokine profile in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1997;41:619–624. doi: 10.1080/15216549700201651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman AB, Torres VE, Perrone RD, et al. The HALT polycystic kidney disease trials: design and implementation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:102–109. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04310709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heffernan KS, Karas RH, Patvardhan EA, et al. Peripheral arterial tonometry for risk stratification in men with coronary artery disease. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:94–98. doi: 10.1002/clc.20705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuvin JT, Patel AR, Sliney KA, et al. Assessment of peripheral vascular endothelial function with finger arterial pulse wave amplitude. Am Heart J. 2003;146:168–174. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Millasseau SC, Guigui FG, Kelly RP, et al. Noninvasive assessment of the digital volume pulse. Comparison with the peripheral pressure pulse. Hypertension. 2000;36:952–956. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly R, Hayward C, Avolio A, et al. Noninvasive determination of age-related changes in the human arterial pulse. Circulation. 1989;80:1652–1659. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.6.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takazawa K, Tanaka N, Takeda K, et al. Underestimation of vasodilator effects of nitroglycerin by upper limb blood pressure. Hypertension. 1995;26:520–523. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurnberger J, Keflioglu-Scheiber A, Opazo Saez AM, et al. Augmentation index is associated with cardiovascular risk. J Hypertens. 2002;20:2407–2414. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200212000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Trijp MJ, Bos WJ, Uiterwaal CS, et al. Determinants of augmentation index in young men: the ARYA study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:825–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smulyan H, Marchais SJ, Pannier B, et al. Influence of body height on pulsatile arterial hemodynamic data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkinson IB, MacCallum H, Flint L, et al. The influence of heart rate on augmentation index and central arterial pressure in humans. J Physiol. 2000;525 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00263.x. Pt 1: 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkinson IB, Mohammad NH, Tyrrell S, et al. Heart rate dependency of pulse pressure amplification and arterial stiffness. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:24–30. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fantin F, Mattocks A, Bulpitt CJ, et al. Is augmentation index a good measure of vascular stiffness in the elderly? Age Ageing. 2007;36:43–48. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McEniery CM, Yasmin Hall IR, et al. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1753–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell GF, Parise H, Benjamin EJ, et al. Changes in arterial stiffness and wave reflection with advancing age in healthy men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 2004;43:1239–1245. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000128420.01881.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clausen P, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Iversen J, et al. Flow-associated dilatory capacity of the brachial artery is intact in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:335–339. doi: 10.1159/000094402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hogas SM, Voroneanu L, Serban DN, et al. Methods and potential biomarkers for the evaluation of endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease: a critical approach. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stam F, van Guldener C, Schalkwijk CG, et al. Impaired renal function is associated with markers of endothelial dysfunction and increased inflammatory activity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:892–898. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato M, Konuma T, Yanagisawa N, et al. Fas-Fas ligand system in the peripheral blood of patients with renal diseases. Nephron. 2000;85:107–113. doi: 10.1159/000045642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woo D. Apoptosis and loss of renal tissue in polycystic kidney diseases. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:18–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kampus P, Muda P, Kals J, et al. The relationship between inflammation and arterial stiffness in patients with essential hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2006;112:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahmud A, Feely J. Arterial stiffness is related to systemic inflammation in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:1118–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000185463.27209.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Booth AD, Wallace S, McEniery CM, et al. Inflammation and arterial stiffness in systemic vasculitis: a model of vascular inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:581–588. doi: 10.1002/art.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verbeke F, Van Biesen W, Peeters P, et al. Arterial stiffness and wave reflections in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3021–3027. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanbay M, Afsar B, Gusbeth-Tatomir P, et al. Arterial stiffness in dialysis patients: where are we now? Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:741–752. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9675-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azurmendi PJ, Fraga AR, Galan FM, et al. Early renal and vascular changes in ADPKD patients with low-grade albumin excretion and normal renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2458–2463. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Latham RD, Rubal BJ, Westerhof N, et al. Nonhuman primate model for regional wave travel and reflections along aortas. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H299–H306. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.2.H299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Latham RD, Westerhof N, Sipkema P, et al. Regional wave travel and reflections along the human aorta: a study with six simultaneous micromanometric pressures. Circulation. 1985;72:1257–1269. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Segers P, Verdonck P. Role of tapering in aortic wave reflection: hydraulic and mathematical model study. J Biomech. 2000;33:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torres VE, King BF, Chapman AB, et al. Magnetic resonance measurements of renal blood flow and disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:112–120. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00910306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levine E, Grantham JJ. Calcified renal stones and cyst calcifications in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: clinical and CT study in 84 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:77–81. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.1.1609726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haydar AA, Covic A, Colhoun H, et al. Coronary artery calcification and aortic pulse wave velocity in chronic kidney disease patients. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1790–1794. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barrett BJ, Foley R, Morgan J, et al. Differences in hormonal and renal vascular responses between normotensive patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and unaffected family members. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1118–1123. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]