Abstract

Background. Previous reports demonstrated that digitalis-like cardiotonic steroids (CTS) contribute to the pathogenesis of end-stage renal disease. The goal of the present study was to define the nature of CTS in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and in partially nephrectomized (PNx) rats.

Methods. In patients with CKD and in healthy controls, we determined plasma levels of marinobufagenin (MBG) and endogenous ouabain (EO) and erythrocyte Na/K-ATPase activity in the absence and in the presence of 3E9 anti-MBG monoclonal antibody (mAb) and Digibind. Levels of MBG and EO were also determined in sham-operated Sprague–Dawley rats and in rats following 4 weeks of PNx.

Results. In 25 patients with CKD plasma, MBG but not EO was increased (0.86 ± 0.07 versus 0.28 ± 0.02 nmol/L, P < 0.01) and erythrocyte Na/K-ATPase was inhibited (1.24 ± 0.10 versus 2.80 ± 0.09 μmol Pi/mL/h, P < 0.01) as compared to that in 19 healthy subjects. Ex vivo, 3E9 mAb restored Na/K-ATPase in erythrocytes from patients with CKD but did not affect Na/K-ATPase from control subjects. Following chromatographic fractionation of uremic versus normal plasma, a competitive immunoassay based on anti-MBG mAb detected a 3-fold increase in the level of endogenous material having retention time similar to that seen with MBG. A similar pattern of CTS changes was observed in uremic rats. As compared to sham-operated animals, PNx rats exhibited 3-fold elevated levels of MBG but not that of EO.

Conclusions. In chronic renal failure, elevated levels of a bufadienolide CTS, MBG, contribute to Na/K-ATPase inhibition and may represent a potential target for therapy.

Keywords: chronic renal failure, marinobufagenin, monoclonal antibody, Na/K-ATPase, ouabain

Introduction

One of the factors implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic renal failure is the increased circulating concentration of endogenous cardiotonic steroids (CTS), i.e. endogenous ligands of the Na/K-ATPase [1, 2]. CTS, belonging to classes of cardenolides [e.g. endogenous ouabain (EO)] and bufadienolides [e.g. marinobufagenin (MBG) and telocinobufagin], act as physiological regulators of sodium pump activity and are implicated in regulation of natriuresis and vascular tone [2]. More recently, CTS have been shown to contribute to pro-hypertrophic and pro-fibrotic cell signaling [3]. We demonstrated that in partially nephrectomized (PNx) rats, diastolic dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis are accompanied by elevated plasma levels of MBG; we also noted increased cardiac and plasma levels of oxidative stress markers as well as other evidence for signaling through the Na/K-ATPase such as activation of Src and MAPK [4–6]. In these studies, chronic administration of MBG to normotensive rats to achieve similar plasma concentrations of MBG as seen with PNx produced a very similar cardiac phenotype as seen with PNx. Conversely, active immunization of PNx rats against MBG dramatically reduced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, as well as evidence of Na/K-ATPase signaling including reduced left ventricular and systemic levels of oxidative stress [4–6].

The above findings suggest that immunoneutralization of CTS may hold promise for the treatment of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and of uremic cardiomyopathy. Since data on the nature of CTS implicated in chronic renal failure are conflicting [6–9], our goal was to define whether EO, MBG or both become elevated in uremia. To answer this question, we determined plasma levels of CTS in patients with CKD and in PNx rats using MBG immunoassay based on a monoclonal antibody (mAb) and two EO assays based on antibodies with different cross-reactivities, as well as an assay utilizing Digibind as the primary antibody. Previously, Digibind™ (the Fab fragments of ovine digoxin antibody) has been demonstrated to both bind endogenous CTS and lower blood pressure in patients with preeclampsia, a syndrome associated with elevated CTS levels [10–12]. We also compared the ability of anti-MBG and anti-ouabain antibodies to interact with CTS material from human uremic plasma following its fractionation on reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) columns.

Methods

Human studies

The protocol for the human study was approved by the Research Council of Mechnikov Medical Academy, St. Petersburg, Russia, and by the Institutional Review Board of Medstar Research Institute, Washington, DC. Twenty-five patients with CKD on chronic dialysis treatment at the Chronic Dialysis Division, Mechnikov Medical Academy, St. Petersburg, Russia, and 19 healthy volunteers (Mechnikov Medical Academy, St. Petersburg, Russia) were included in this study. Of the patients, 20 were on hemodialysis (HD) and 5 on chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). The cause of CKD was chronic glomerulonephritis (12 patients), pyelonephritis (4 patients), polycystic kidney disease (4 patients), congenital renal dysplasia (1 patient), diabetes mellitus (3 patients) and amyloidosis (1 patient). Patients on HD were treated three times weekly with standard bicarbonate dialysis with synthetic membranes. Patients on CAPD were all on a four exchanges per day schedule with standard 2 L peritoneal dialysate containing varying amounts of dextrose (1.5, 2.5 or 4.25%) depending on their volume status. Twelve patients were on treatment with erythropoietin, and 16 were taking antihypertensive drugs (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, alpha- and beta-blockers). None of the subjects studied had ever been administered digitalis drugs. The clinical characteristics of the patients and control subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjectsa

| Control (n = 19) | CKD (n = 25) | |

| Age (years) | 46.5 ± 2.4 | 52.8 ± 3.7 |

| Sex (male/female) | 9/10 | 14/11 |

| Body weight (kg) | 68 ± 3 | 71 ± 2 |

| HD/CAPD | n.a. | 20/5 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 86 ± 2 | 848 ± 45* |

| Serum Na (mmol/L) | 141 ± 1 | 139 ± 1 |

| Serum K (mmol/L) | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 125 ± 2 | 127 ± 4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76 ± 1 | 81 ± 3 |

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 0/19 | 16/9 |

Means ± SEM.

P < 0.001 versus healthy subjects, two-tailed t-test. n.a, not applicable.

Erythrocyte Na/K-ATPase activity

Activity of Na/K-ATPase in the whole erythrocytes of patients with CKD and control subjects was determined as reported previously [13]. The in vitro effects of anti-MBG 3E9 mAb and Digibind (Glaxo SmithKline) on erythrocyte Na/K-ATPase were studied in red blood cells from patients with CKD. Anti-MBG 3E9 mAbs were used at concentration 50 μg/L, which, in vitro, reversed the MBG-induced 75% inhibition of rat kidney Na/K-ATPase (α-1 isoform) and in vivo reduced blood pressure in hypertensive Dahl-S rats [14]. Digibind was used at concentration 10 μg/mL, which, is in the same range as doses of Digibind previously used to treat patients with preeclampsia [10–12]. Aliquots of the whole blood (0.5 mL) were preincubated at room temperature for 30 min in the presence and absence of 3E9 mAb or Digibind. Erythrocytes were washed three times in an isotonic medium (145 mmol/L NaCl in 20 mmol/L Tris buffer; pH 7.6 at 4°C), and activity of Na/K-ATPase was determined. Erythrocytes were preincubated with Tween-20 (0.5%) in sucrose (250 mmol/L) and Tris buffer (20 mmol/L, pH 7.4, 37°C) for 30 min and were incubated for 30 min in the medium containing (in mmol/L) NaCl 100, KCl 10, MgCl2 3, EDTA 0.5, Tris 50 and ATP 2 (pH 7.4, 37°C) in the final dilution 1:40. The reaction was stopped by the addition of trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 7%. Total ATPase activity was measured by the production of inorganic phosphate (Pi), and Na/K-ATPase activity was estimated as the difference between ATPase activity in the presence and absence of 5 mmol/L ouabain.

Animal studies

All animal experimentation described in this article was conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under protocols approved by the University of Toledo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–300 g) were used for these studies. Eight sham-nephrectomized rats comprised the control group. In 18 rats, PNx was performed as we have previously described [4]. This maneuver produces sustained hypertension within 2 weeks. At 5 weeks following PNx, these rats were sacrificed. Plasma samples were stored at −80°C for determination of CTS. Blood pressure was determined using the tail cuff method by IITC, Inc. (Amplifier model 229, Monitor model 31, Test chamber Model 306; IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA).

Creatinine measurement

Plasma creatinine was measured with a colorimetric method using a commercial kit from Teco Diagnostics (Cat# C515-480; Anaheim, CA). Creatinine standards or plasma samples were mixed with the picric acid reagent and creatinine buffer reagent provided with the kit. The OD value at 510 nm was measured immediately after and at 15 min. The differences between the two time points were used to calculate the creatinine concentrations.

Oxidative stress markers

Total protein carbonyl concentration in plasma and left ventricular homogenate as a marker of oxidative stress [15] was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using the BIOCELL PC Test kit (Northwest Life Science Specialties).

CTS immunoassays

For measurement of CTS, plasma samples were extracted using C18 SepPak cartridges (Waters Inc., Cambridge, MA) [16]. Cartridges were activated with 10 mL acetonitrile and washed with 10 mL water. Then, 0.5 mL plasma samples were applied to the cartridges and consecutively eluted with 7 mL 20% acetonitrile followed by 7 mL 80% acetonitrile in the same vial, which provides elution of material with lower and higher polarity, respectively, and permits measurement of various CTS in the sample [16]. Following elution, samples were vacuum dried and kept at −50°C. Before immunoassays, samples were reconstituted in the initial volume of assay buffer. MBG was measured using a fluoroimmunoassay [association-enhanced fluoroimmunoassay (DELFIA)] based on a murine anti-MBG 4G4 mAb recently described in detail [14]. This assay is based on competition between immobilized antigen (MBG-glycoside-thyroglobulin) and MBG, other cross-reactants, or endogenous CTS within the sample for a limited number of binding sites on an anti-MBG mAbs. Secondary (goat anti-mouse) antibody labeled with nonradioactive europium was obtained from Perkin-Elmer (Waltham, MA). The EO assays were based on a similar principle utilizing an ouabain–ovalbumin conjugate and two ouabain antiserums (anti-OU-S, 1:100 000 and anti-OU-M, 1:20 000) obtained from rabbits immunized with ouabain–bovine serum albumin (BSA) conjugate (anti-OU-S) or with a mixture of ouabain–BSA and ouabain–RNAase conjugates (anti-OU-M). Plasma levels of digoxin-like immunoreactivity were determined using a competitive immunoassay based on Digibind [14]. Since levels of ‘digoxin immunoreactivity’ in the individual (nonconcentrated), samples in this assay are beyond its sensitivity, levels of digoxin-like immunoreactive material in plasma of patients with CKD and PNx rats were determined in the samples which were pooled (n = 6), extracted of C18 cartridges and concentrated 10-fold. For this digoxin immunoassay, we labeled the primary antibody (Digibind; Glaxo SmithKline, King of Prussia, PA) using a europium-labeling kit (Perkin-Elmer). The assay was based on a competition between the CTS in the sample and digoxin–BSA conjugate immobilized on the bottom of immunoprecipitation strips for a limited number of binding sites of the Digibind (0.125 μg/well). The sensitivity of Digibind immunoassay for digoxin was 0.01 nmol/L. In a separate experiment, we pooled 50-μL aliquots of control plasma samples, spiked 0.25 mL samples of pooled plasma with increasing concentrations of MBG (0.125–2 nmol/L), extracted samples of on C18 SepPak cartridges as described above and determined levels of MBG and of ouabain-like immunoreactivity using assays based on anti-ouabain antibodies ‘S’ and ‘M’.

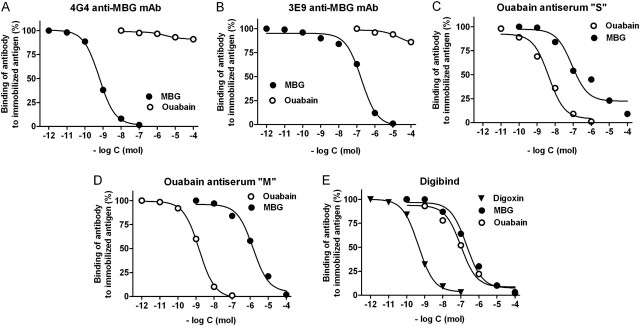

Data on cross-reactivity of each assay and calibration curves from immunoassays illustrating cross-reactivity of each antibody with MBG, ouabain and digoxin are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1, respectively. MBG and telocinobufagin (>98% HPLC pure) were purified from secretions from parotid glands of Bufo marinus toads as reported previously [13]. Bufalin, cinobufagin, cinobufatalin and ouabain were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Proscillaridin A and resibufagenin were obtained from Axxora LLC (San Diego, CA), and marinobufotoxin was a generous gift by Dr. Vincent P. Butler, Department of Medicine, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Table 2.

Cross-immunoreactivity of anti-MBG and anti-ouabain antibodies

| Cross-reactants | Cross-immunoreactivity of antibodies (%) |

||||

| Anti-MBG 4G4 mAb | Anti-MBG 3E9 mAb | Digibind | Anti-ouabain serum S | Anti-ouabain serum M | |

| Marinobufagenin | 100 | 100 | 0.2 | 7 | 0.05 |

| Marinobufotoxin | 43 | 4 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.06 |

| Telocinobufagin | 14 | 7 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.02 |

| Cinobufotalin | 40 | 44 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 0.02 |

| Cinobufagin | 0.07 | 1.4 | 0.02 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Resibufagenin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.15 |

| Bufalin | 0.08 | 0.3 | 2.7 | 6 | 0.1 |

| Proscillaridin A | <0.001 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.03 |

| Ouabain | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 100 | 100 |

| Ouabagenin | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1 | 25 | 52 |

| Digoxin | 0.03 | 1.8 | 100 | 0.1 | 1.5 |

| Digitoxin | <0.01 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.47 |

| Aldosterone | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Progesterone | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.08 | 0.002 |

| Prednisone | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | 0.07 | 0.001 |

Fig. 1.

Displacement of binding of anti-MBG 4G4 (A) and 3E9 (B) mAbs, anti-ouabain S antiserum (C), anti-ouabain M antiserum (D) and Digibind (E) to conjugated antigens by cardiotonic steroids in a competitive fluoroimmunoassays.

High-performance liquid chromatography

The 50-μL alliquotes of uremic or control plasma samples were pooled. Pooled normal or uremic plasma (0.5 mL) was extracted on C18 SepPak cartridges, as described above, dried in a vacuum centrifuge and fractionated on an Agilent 1100 series liquid chromatographic system. Specifically, this involved the use of an Agilent Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), 4.6_150mm, 5-μm particle size, 80A° column, a flow rate of 1 mL/min and a linear (10–85.5%) gradient of acetonitrile against 0.1% trifluoroacetic (TFA) for 45 min. Thirty 1.5-min fractions were collected and analyzed for MBG and ouabain immunoreactivity.

Statistical analyses

The results are presented as means ± SEM. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Newman–Keuls test and by two-tailed t-test (when applicable) (GraphPad Prism software, San Diego, CA). A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

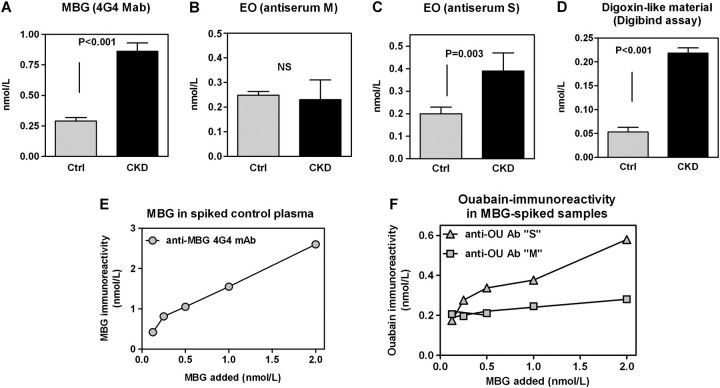

Patients with CKD did not differ significantly from the control group with respect to age, gender and body mass (Table 1). As presented in Figure 2, patients with CKD had 3.5-fold greater plasma levels of MBG as compared to that in the control group. When EO concentrations were determined by an assay based on anti-ouabain antibody M, levels of this hormone in patients with CKD were not different from control values but the assay based on antibody S, which exhibits cross-immunoreactivity with bufadienolides, detected an almost 2-fold elevation of EO in patients with chronic renal failure. The assay based on Digibind did not detect immunoreactivity in individual samples of plasma from both CKD and control groups (data not shown). When samples from each group were pooled and concentrated 10-fold, levels of CTS measured by Digibind fluoroimmunoassay in patients with CKD were increased 4-fold versus that in control group, which was proportional to the observed increase in the plasma levels of MBG seen in these patients (Figure 2D). In order to confirm that anti-ouabain antibody S indeed exhibits greater cross-reactivity with MBG as compared to anti-ouabain antibody M, we pooled aliquots of control plasma, spiked it with MBG (Figure 2E), extracted them on C18 SepPak cartridges and determined levels of MBG and ouabain-like immunoreactivity using both anti-ouabain antibodies. As presented in Figure 2F, anti-ouabain antibody S detected elevation in the levels of MBG much better than anti-ouabain antibody M.

Fig. 2.

Plasma levels of MBG measured using 4G4 anti-MBG mAb (A) and of EO measured using anti-ouabain antiserums M (B) and S (C) in healthy controls (Ctrl) and in patients with CKD. (D) Determination of levels of CTS in pooled samples of plasma from Ctrl and CKD using competitive fluoroimmunoassay based on Digibind. Means ± SEM. Two-tailed t-test. Determination of MBG immunoreactivity (4G4 mAb) (E) and of ouabain immunoreactivity determined using anti-ouabain antiserums M and S (F) in pooled plasma samples from healthy controls spiked with MBG (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2 nmol/L).

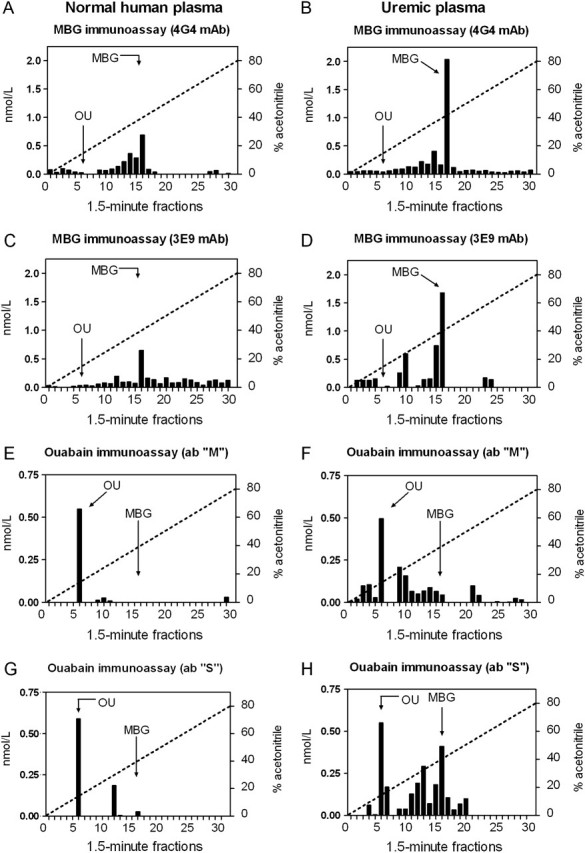

Figure 3A and C demonstrate the elution of endogenous MBG-immunoreactive material from control plasma from the Agilent Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 HPLC column. Standard of MBG eluted in fraction 16, as indicated on the graphs by an arrow. Endogenous MBG-immunoreactive material from normal, determined using both 4G4 and 3E9 anti-MBG mAbs, eluted in fractions 9–29 with a distinctive peak of immunoreactivity eluting in fraction 16, which coincided with the elution time of MBG standard. Following HPLC fractionation of uremic plasma levels of MBG, immunoreactivity eluting in fraction 16 exhibited a substantial increase versus that in control plasma (Figure 3B and D). The magnitude of this increase was proportional to the magnitude in the elevation in plasma MBG levels in CKD patients.

Fig. 3.

Pattern of elution of endogenous MBG and ouabain immunoreactivity following fractionation of extracts of normal human plasma (A, C, E and G) and of human uremic plasma (B, D, F and H) on reverse-phase HPLC column in the linear gradient of acetonitrile (dotted line). The retention times of MBG and ouabain (OU) standards are indicated by arrows.

As presented in Figure 3E and G, the maximum of endogenous ouabain-immunoreactive material detected by both S and M anti-ouabain antibodies eluted from HPLC column in fraction 6, which corresponds to the elution tome ouabain standard. Following HPLC fractionation of uremic plasma, both anti-ouabain antibodies did not detect an increase in the levels of EO in HPLC fraction eluting in fraction 6. Anti-ouabain antibody M detected a modest increase in the ouabain-immunoreactivity eluting in fractions 9–16, while antibody S detected a substantial increase in ouabain immunoreactivity eluting in fractions 11–17 (Figure 3F and H), which overlaps with the elution time of MBG and other bufadienolide CTS (telocinobufagin, fraction 14; MBG, fraction 16; cinobufatalin, fraction 16 and bufalin, fraction 17).

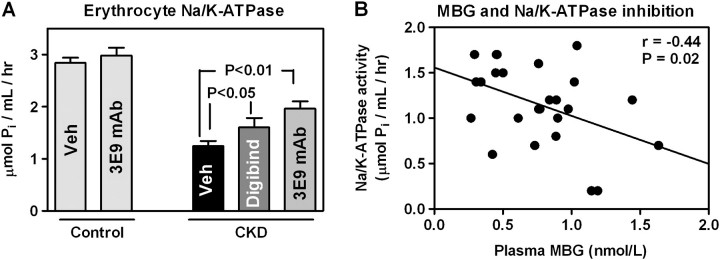

As presented in Figure 4A, in patients with CKD activity of the Na/K-ATPase in erythrocytes was inhibited by 56% as compared to that in the control group and was negatively correlated with plasma concentrations of MBG (Figure 4B) but not EO (r = 0.34, P = 0.30 for EO measured with antibody M and r = 0.45, P = 0.16 for EO measured with antibody S). The ex vivo treatment of erythrocytes from patients with CKD with 3E9 anti-MBG mAb and with Digibind produced a partial but significant restoration of Na/K-ATPase activity (Figure 4A). Notably, the ex vivo treatment with 3E9 antibody did not significantly alter the activity of the Na/K-ATPase in erythrocytes from control subjects.

Fig. 4.

(A) Erythrocyte Na/K-ATPase in healthy control subjects and in patients with CKD in the absence and in the presence of Digibind and 3E9 anti-MBG mAb. Means ± SEM. One-way analysis of variance followed by Newman–Keuls test. (B) Correlation between plasma levels of MBG and activity of Na/K-ATPase in erythrocytes in patients with CKD. Two-tailed t-test.

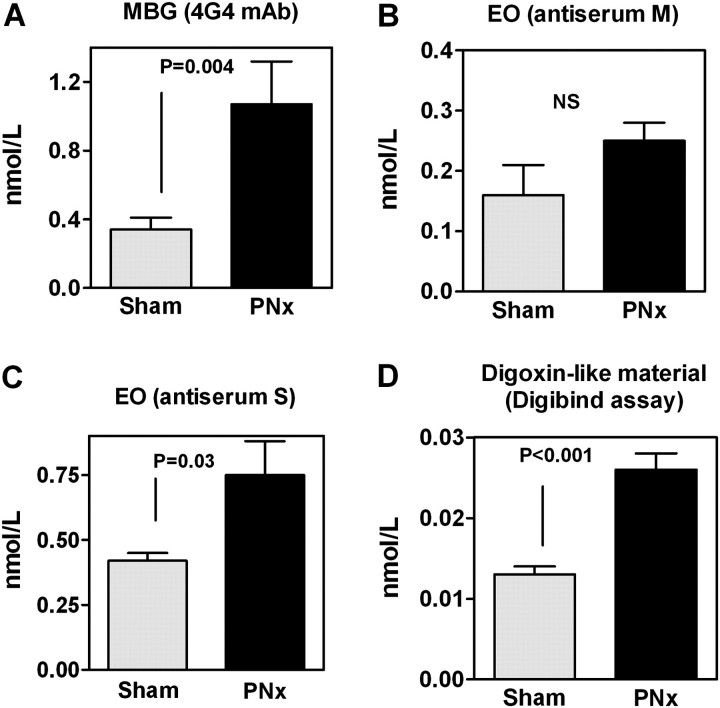

In order to define whether in PNx rats changes in CTS mimic those observed in patients with CKD, we next determined levels of MBG, EO and digoxin immunoreactivity in intact Sprague–Dawley rats in the animals with renal failure. In Sprague–Dawley rats, PNx led to marked increases in plasma creatinine, development of hypertension and oxidative stress assessed by plasma and cardiac levels of carbonylated protein (Table 3). As illustrated in Figure 5, patterns of changes in plasma levels of CTS in PNx rats were identical to those observed in patients with CKD. In Sprague–Dawley rats, PNx was accompanied by significant elevations of MBG measured by 4G4 mAb and EO determined using antiserum S but not antiserum M. DELFIA digoxin assay based on Digibind detected elevated levels of CTS in pooled 10-fold concentrated samples of plasma from PNx versus control rats. Similar to that in patients with CKD, in PNx rats, the magnitude of elevation of plasma CTS determined using Digibind was proportional to that determined using assay based on anti-MBG 4G4 mAb.

Table 3.

Physiological measurements after PNxa

| Variable | Sham (n = 8) | PNx (n = 6) |

| Plasma creatinine, mg/dL | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.64 ± 0.03* |

| Systolic blood pressure | 110 ± 5 | 189 ± 14* |

| HW/BW, ×102 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.36 ± 0.03* |

| Left ventricular carbonylated protein, pmol/mg protein | 319 ± 7 | 514 ± 20* |

| Plasma carbonylated protein, pmol/mg protein | 171 ± 9 | 320 ± 20* |

Systolic blood pressure measured in conscious animals with a tail cuff at the indicated time points 4 weeks post surgery. BW, body weight; HW, heart weight determined at the time of euthanasia.

P < 0.01 versus Sham.

Fig. 5.

CTS in rats with renal failure. Plasma levels of MBG measured using 4G4 anti-MBG mAb (A) and of EO measured using antiserums M (B) and S (C) in sham-operated (Sham) and PNx rats. (D) Determination of levels of CTS in pooled samples of plasma from Sham and PNx using competitive fluoroimmunoassay based on Digibind. Means ± SEM. Two-tailed t-test.

Discussion

The major findings of the present study are that levels of CTS in patients and in experimental rats with chronic renal failure exhibit a similar pattern of changes and that MBG rather than EO becomes elevated and contributes to Na/K-ATPase inhibition in CKD. Since in chronic renal failure CTS represent potentially important therapeutic targets, the importance of determination of the nature of CTS implicated in pathogenesis of CKD is obvious. Elevations of CTS in uremic subjects [17] and in PNx rats [18, 19] have been found long ago, and detection of false-positive digitalis immunoreactivity in uremic serum was among the first findings indicating the importance of endogenous digitalis-like CTS in volume-expanded hypertension and renal failure [17]. Data on the nature of CTS implicated in chronic renal failure are controversial. Naruse et al. [7] reported increased plasma levels of ouabain immunoreactivity in uremic subjects. Recently, Stella et al. [9] demonstrated that levels of EO in plasma of patients with CKD substantially exceeded those observed in normotensive subjects in the other studies. Schoner et al. [20], however, demonstrated that ouabain-like CTS which becomes elevated in uremic plasma is more hydrophobic than ouabain which is consistent with the profile of elution of MBG from reverse-phase HPLC columns in our present (Figure 3) and previous [14, 16] studies. Accordingly, Tao et al. [21] demonstrated that CTS purified from peritoneal dialysate of patients with chronic renal failure exhibits heightened affinity to α-1 rather that to α2/α-3 isoforms of the Na/K-ATPase, which is similar to profile of inhibition of Na/K-ATPase isoforms by MBG [22, 23]. Subsequently, using assays based on polyclonal antibodies, we demonstrated that levels of MBG rather than EO are elevated in the plasma of patients with CKD [8].

In the present study, using a competitive immunoassay based on a monoclonal antibody, which is highly specific to bufadienolide CTS, we demonstrate that levels of MBG are markedly increased in both patients with CKD and in rats following subtotal nephrectomy. In the present study, both anti-MBG mAbs used for measurement of CTS and for ex vivo CTS immunoneutralization exhibited extremely low cross-reactivity with ouabain, and the pattern of uremia-induced changes in the levels of CTS was identical in both patients with CKD and rats subjected to PNx. In our study, for determination of EO, we used two anti-ouabain antibodies, an antiserum S, which exhibits a substantial cross-immunoreactivity with bufadienolide CTS including MBG, and antiserum M, which does not cross-react with the bufadienolides (Table 1). We found that in both uremic patients and PNx rats, elevations of EO were detected by antibody S but not by antibody M. Notably, following HPLC fractionation of uremic plasma, anti-ouabain antibody M cross reacted with the material coeluting with authentic ouabain, while anti-ouabain antibody S in addition to less polar material, which coeluted with ouabain, also reacted with more polar HPLC fractions, which overlapped with the fractions containing high levels of MBG immunoreactivity. These observations do not agree with the previous finding of elevated EO levels in patients with CKD [7, 9] and suggest that it is MBG, rather than EO, which becomes elevated with renal failure. Ergo, we believe it is MBG that represents the more logical therapeutic target in this condition, especially considering that in PNx rats active immunization against MBG reduced levels of cardiac oxidative stress and fibrosis [5], the hallmarks of uremic cardiomyopathy [24, 25]. It should be noted that in previous studies demonstrating elevated EO levels in patients with CKD and in PNx rats, data on cross-reactivity of anti-ouabain antibody with bufadienolide CTS were not reported [7, 9, 20]. Considering substantial variability in plasma levels of EO reported by various groups [26], the standardization of the ‘in-house’ CTS assays and development of reliable commercial immunoassays preferably based on monoclonal antibodies will be essential for subsequent clinical studies of endogenous sodium pump ligands.

Previously, we demonstrated that in patients with preeclampsia-elevated plasma, MBG levels were associated with the inhibition of erythrocyte Na/K-ATPase which was reversible by both 3E9 mAb and Digibind [14] and that in preeclamptic placentae, bufadienolide CTS, including MBG, rather than EO, represents a target for Digibind [27]. In the present study, both 3E9 mAb and Digibind ex vivo restored activity of Na/K-ATPase in erythrocytes from patients with CKD. Furthermore, in the present study, plasma levels of MBG exhibited a negative correlation with Na/K-ATPase, indicating on a causative link between elevated levels of MBG and inhibited Na/K-ATPase in patients with CKD. These observations agree with the results of several previous studies in which activity of erythrocyte Na/K-ATPase was shown to reflect plasma levels of endogenous [13, 14, 28, 29] and exogenous [30–32] CTS and in which ex vivo incubation of plasma in the presence of CTS-neutralizing antibodies reversed CTS-induced inhibition of Na/K-ATPase in the erythrocytes from newborns [28], from human subjects during voluntary hypoventilation [13] and from NaCl-loaded Dahl-S rats [33]. Our present and previous observations that Digibind detects elevated levels of CTS in plasma from patients with CKD, reverses CTS-induced Na/K-ATPase inhibition and reduces blood pressure in experimental NaCl-induced hypertension [14] suggest that Digibind could be used clinically for immunoneutralization of heightened CTS levels in these patients.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (O.V.F., G.P. and A.Y.B.) and by NIH grant HL071556 (J.I.S.). The authors are grateful to Anton Bzhelyansky, MA (MedStar Research Institute, Hyattsville, MD), for advice and HPLC analyses.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Ritz E. Uremic cardiomyopathy—an endogenous digitalis intoxication? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1493–1497. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagrov AY, Shapiro JI. Endogenous digitalis: pathophysiologic roles and therapeutic applications. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4:378–392. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagrov AY, Shapiro JI, Fedorova OV. Endogenous cardiotonic steroids: physiology, pharmacology, and novel therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:9–38. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy DJ, Vetteth S, Periyasamy SM, et al. Central role for the cardiotonic steroid marinobufagenin in the pathogenesis of experimental uremic cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2006;47:488–495. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000202594.82271.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elkareh J, Kennedy DJ, Yashaswi B, et al. Marinobufagenin stimulates fibroblast collagen production and causes fibrosis in experimental uremic cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2007;49:215–224. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252409.36927.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elkareh J, Periyasamy SM, Shidyak A, et al. Marinobufagenin induces increases in procollagen expression in a process involving protein kinase C and Fli-1: implications for uremic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1219–F1226. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90710.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naruse K, Naruse M, Tanabe A, et al. Does plasma immunoreactive ouabain originate from the adrenal gland? Hypertension. 1994;23(1 Suppl):I102–I105. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.1_suppl.i102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonick HC, Ding Y, Vaziri ND, et al. Simultaneous measurement of marinobufagenin, ouabain, and hypertension-associated protein in various disease states. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1998;20:617–627. doi: 10.3109/10641969809053240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stella P, Manunta P, Mallamaci F, et al. Endogenous ouabain and cardiomyopathy in dialysis patients. J Intern Med. 2008;263:274–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodlin RC. Antidigoxin antibodies in eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:518–559. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198802253180815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adair CD, Buckalew V, Taylor K, et al. Elevated endoxin-like factor complicating a multifetal second trimester pregnancy: treatment with digoxin-binding immunoglobulin. Am J Nephrol. 1996;16:529–531. doi: 10.1159/000169054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adair CD, Luper A, Rose JC, et al. The hemodynamic effects of intravenous digoxin-binding fab immunoglobulin in severe preeclampsia: a double-blind, randomized, clinical trial. J Perinatol. 2009;29:284–289. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagrov AY, Fedorova OV, Austin-Lane JL, et al. Endogenous marinobufagenin-like immunoreactive factor and Na+, K+ ATPase inhibition during voluntary hypoventilation. Hypertension. 1995;26:781–788. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fedorova OV, Simbirtsev AS, Kolodkin NI, et al. Monoclonal antibody to an endogenous bufadienolide, marinobufagenin, reverses preeclampsia-induced Na/K-ATPase inhibition and lowers blood pressure in NaCl-sensitive hypertension. J Hypertens. 2008;26:2414–2425. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328312c86a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine RL, Williams JA, Stadtman ER, et al. Carbonyl assays for determination of oxidatively modified proteins. Meth Enzymol. 1994;233:346–357. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)33040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopatin DA, Ailamazian EK, Dmitrieva RI, et al. Circulating bufodienolide and cardenolide sodium pump inhibitors in preeclampsia. J Hypertens. 1999;17:1179–1187. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917080-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graves SW, Brown B, Valdes R., Jr An endogenous digoxin-like substance in patients with renal impairment. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:604–608. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-5-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huot SJ, Pamnani MB, Clough DL, et al. The role of sodium intake, the Na+-K+ pump and a ouabain-like humoral agent in the genesis of reduced renal mass hypertension. Am J Nephrol. 1983;3:92–99. doi: 10.1159/000166698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pamnani MB, Bryant HJ, Harder DR, et al. Vascular smooth muscle membrane potentials in rats with one-kidney, one clip and reduced renal mass-saline hypertension: the influence of a humoral sodium pump inhibitor. J Hypertens Suppl. 1985;3:S29–S31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoner W, Heidrich-Lorsbach E, Kirch U, et al. Purification and properties of endogenous ouabain-like substances from hemofiltrate and adrenal glands. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;22(Suppl 2):S29–S31. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199322002-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tao QF, Soszynski PA, Hollenberg NK, et al. Specificity of the volume-sensitive sodium pump inhibitor isolated from human peritoneal dialysate in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1996;49:420–429. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fedorova OV, Bagrov AY. Inhibition of Na/K ATPase from rat aorta by two endogenous Na/K pump inhibitors, ouabain and marinobufagenin. Evidence of interaction with different alpha-subinit isoforms. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:929–935. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedorova OV, Kolodkin NI, Agalakova NI, et al. Marinobufagenin, an endogenous α-1 sodium pump ligand, in hypertensive Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2001;37:462–466. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.London GM. Cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure: pathophysiologic aspects. Semin Dial. 2003;16:85–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2003.16023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Himmelfarb J, Stenvinkel P, Ikizler TA, et al. The elephant in uremia: oxidant stress as a unifying concept of cardiovascular disease in uremia. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1524–1538. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholls MG, Lewis LK, Yandle TG, et al. Ouabain, a circulating hormone secreted by the adrenals, is pivotal in cardiovascular disease. Fact or fantasy? J Hypertens. 2009;27:3–8. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831101d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fedorova OV, Tapilskaya NI, Bzhelyansky AM, et al. Interaction of Digibind with endogenous cardiotonic steroids from preeclamptic placentae. J Hypertens. 2010;28:361–366. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328333226c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boero R, Guarena C, Deabate MC, et al. Erythrocyte Na+, K+ pump inhibition after saline infusion in essentially hypertensive subjects: effects of canrenone administration. Int J Cardiol. 1989;25(Suppl 1):S47–S52. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(89)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balzan S, Montali U, Pieraccini L, et al. The stimulatory effect on human erythrocyte rubidium-86 uptake by anti-cardiac-glycoside antibodies. Q J Nucl Med. 1995;39:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curd J, Smith TW, Jaton JC, et al. The isolation of digoxin-specific antibody and its use in reversing the effects of digoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2401–2406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.10.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang W-H, Askari A. Red cell Na+, K+-ATPase: a method for estimating the extent of inhibition of an enzyme sample containing an unknown amount of bound cardiac glycoside. Life Sci. 1975;16:1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(75)90310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cumberbatch M, Zareian K, Davidson C, et al. The early and late effects of digoxin treatment on the sodium transport, sodium content and Na+K+- ATPase or erythrocytes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;11:565–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fedorova OV, Talan MI, Agalakova NI, et al. Endogenous ligand of alpha(1) sodium pump, marinobufagenin, is a novel mediator of sodium chloride-dependent hypertension. Circulation. 2002;105:1122–1127. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]