Abstract

Gametogenesis is a fundamental aspect of sexual reproduction in eukaryotes. In the unicellular fungi Saccharomyces cerevisiae (budding yeast) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (fission yeast), where this developmental programme has been extensively studied, entry into gametogenesis requires the convergence of multiple signals on the promoter of a master regulator. Starvation signals and cellular mating-type information promote the transcription of cell fate inducers, which in turn initiate a transcriptional cascade that propels a unique type of cell division, meiosis, and gamete morphogenesis. Here, we will provide an overview of how entry into gametogenesis is initiated in budding and fission yeast and discuss potential conserved features in the germ cell development of higher eukaryotes.

Keywords: entry into gametogenesis, meiosis, germ cell, sporulation, master regulator, yeast

1. Introduction

A fundamental aspect of cell-fate decisions is to convert temporary changes in gene expression induced by external signals into a stable phenotype. A crucial and highly coordinated cell-fate decision is the production of gametes (sex cells) from diploid progenitor cells in a process known as gametogenesis. An essential aspect of gametogenesis is the specialized cell division, meiosis, during which the diploid genome of the progenitor cell is reduced to the haploid state by two consecutive chromosome segregations to produce gametes. Thus, the two key aspects of gametogenesis are the expression (i) of genes that transform the canonical mitotic cell division programme into the specialized meiotic division pattern and (ii) of a morphogenesis programme that produces gametes.

Given that proper production of gametes is critical for sustaining a sexually reproducing species, it is important to understand how this cell fate is established. In this review, we will discuss how gametogenesis is induced. First, we will review how entry into the gametogenesis, known as sporulation, is controlled in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and how convergence of many signals at a single promoter plays a pivotal role in this process. A similar overview will be given of the events governing gamete formation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. We will end by highlighting which gametogenesis-inducing processes are conserved and speculate how the principles uncovered in the two model organisms could provide insights into how germ cell-fate determination occurs in mammals.

2. Cell-fate decisions in response to poor growth conditions in budding yeast

When nutrients are limiting, several cell adaptation strategies can be induced. In response to severe nutrient deprivation, haploid and diploid cells enter a quiescent G1 state. When nitrogen is limiting, cells switch from growth by budding to growth by filamentation, in which cells form long-branched chains of elongated cells also known as pseudohyphae. Both haploid and diploid cells can form pseudohyphae, and this cell type is employed to forage for new food sources by enabling invasion and survival in host tissues. Last but not least, nitrogen starvation and the lack of a fermentable carbon source trigger gametogenesis, known as sporulation in yeast. This developmental choice is restricted to MATa/MATα diploid cells that are respiratory competent (have functional mitochondria). In what follows, we will discuss the signals that lead to this developmental decision.

3. Sporulation is governed by IME1

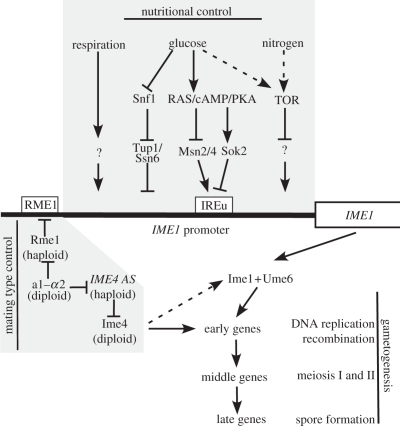

Mating-type information, respiratory state and nutritional information all converge at a single promoter, the IME1 promoter. IME1 (inducer of meiosis 1) is the master regulator of gametogenesis and encodes a transcription factor that activates the expression of the so-called early meiotic genes (figure 1) [1]. Ime1 induces the expression of genes important for pre-meiotic DNA replication, genes essential for meiosis-specific chromosome remodelling and genes encoding factors essential for homologous recombination [2–4]. Ime1 also sets in motion the subsequent events of the sporulation programme. Among the genes whose expression, albeit indirectly, depends on Ime1 is NDT80, which encodes a transcription factor. Ndt80, through an autoregulatory positive feedback loop, induces a wave of transcripts called the ‘middle genes’ (figure 1) [3,5]. Once NDT80-dependent genes are induced, cells are irreversibly committed to meiosis because this group of genes bring about and regulate the processes necessary for entry into and progression through the two meiotic chromosome segregation phases [6]. After the induction of middle genes a third wave of transcripts called the ‘late genes’ is initiated, which control spore formation.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the signals controlling entry into sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nutritional signals, respiration and mating-type control converge at the IME1 promoter to induce gametogenesis. Ime1 together with Ume6 induces the transcription of early meiotic genes. Subsequently, a cascade of middle and late meiotic genes is induced to complete the sporulation programme. See text for details.

Successful completion of sporulation also requires that genes responsible for vegetative growth are repressed. During vegetative growth, S. cerevisiae proliferates by budding. During sporulation, budding is repressed and pre-meiotic S phase and the two meiotic divisions occur within the confines of the mother cell. Sporewalls are then produced around the four meiotic products and the mother cell remnants become the ascus sack that surrounds the four spores. During vegetative growth, budding and the initiation of DNA replication are induced by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) Cdc28 complexed with G1 cyclins (Cln1, 2 or 3). Their expression needs to be inhibited to prevent budding. Nutritional starvation represses CLN expression, thus inhibiting budding. However, DNA replication also relies on Cln–CDKs. How can pre-meiotic DNA replication occur in the absence of Cln–CDK function? The sporulation-specific protein kinase Ime2 takes over Cln–CDK's role in promoting DNA replication [7]. IME2 transcription is induced by Ime1 [8]. Thus, Ime1 ensures that pre-meiotic DNA replication occurs in the absence of Cln–CDK activity and it sets in motion the programme that culminates in the halving of the genome and the production of spores. Understanding what governs IME1 gene expression thus lies at the heart of understanding the basis of gamete formation in budding yeast.

4. The IME1 promoter functions as a signal integrator

Initiation of the sporulation programme requires the following events:

— glucose must be absent from the growth medium,

— nitrogen must be absent from the growth medium,

— Cln–CDKs must be repressed,

— cell must use a non-fermentable carbon source, and thus be respiratory competent, and

— cells must be of the MATa/MATα mating type.

These signals converge at the IME1 promoter (figure 1). This promoter is over 2 kilobases in length, which makes it one of the largest and most regulated promoters in S. cerevisiae. The importance of IME1 transcriptional regulation is revealed when IME1 expression is mis-regulated. The nutritional control of IME1 can be partially suppressed by over-expressing IME1, leading to sporulation in the presence of ample nutrients [9]. Haploid cells can also be induced to sporulate by the over-expression of IME1. This causes a meiotic catastrophe and cell death [10]. Together, these observations illustrate the importance of controlling IME1 expression. In what follows, we will describe our current state of knowledge of how the various signals described above affect IME1 expression. To sum up, a number of important players have been identified, but many of the details of regulation need to be worked out.

5. Glucose represses IME1 expression via multiple mechanisms

In the presence of glucose, budding yeast displays an almost exclusively fermentative metabolism, which results in the excretion of ethanol and low respiratory activity. The Ras/protein kinase A (PKA) signalling pathway is activated by glucose. The Ras guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase), anchored in the plasma membrane, is activated by glucose by an unknown mechanism. Ras–GTP activates adenylate cyclase (CYR1) to produce cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). cAMP binds to the inhibitory subunit of PKA called Bcy1, and induces its dissociation from PKA (Tpk1, 2 and 3 in budding yeast). High PKA levels promote vegetative growth and repress pseudohyphal growth, quiescence and sporulation. The importance of low PKA pathway activity for entry into sporulation has been revealed by mutations that affect PKA pathway activity. A constitutively active allele of RAS2, RAS2Val19, prevents sporulation in nutrient-poor conditions [11]. Similarly, inactivation of BCY1 results in constitutively active PKA and an inability to sporulate [11]. Conversely, deletion of one of the two RAS genes in yeast, RAS2, allows sporulation in rich medium [11]. Loss-of-function mutations in CYR1 induce sporulation even in the presence of high glucose and nitrogen [11].

PKA has multiple targets, among which are several transcription factors. For example, two stress-related transcription factors called Msn2 and Msn4 are kept inactive by PKA [12]. When PKA activity drops, Msn2 is dephosphorylated and translocates into the nucleus where it activates transcription of genes that harbour a stress-response element (STRE) in their promoters [13,14]. The STRE, which is also present within a 32 basepairs (bp) region (called IREu) of the IME1 promoter, can bind Msn2 and Msn4 in vitro [15]. In vivo this region of the IME1 promoter responds to MSN2 and MSN4 activity [15]. Whether Msn2 and Msn4 are the only transcriptional regulators of IME1 that are inhibited by the PKA pathway remains to be determined. It is however clear that PKA not only inhibits IME1 transcriptional activators, but also activates repressors of IME1 expression. The transcriptional repressor Sok2 is phosphorylated by PKA to repress IME1 transcription in the presence of glucose [16,17]. The binding site of Sok2 in the IME1 promoter overlaps with that of Msn2/4, and it has been suggested that they compete in the regulation of IME1 expression [16]. A third target of PKA that regulates IME1 expression is Rim15. This protein kinase, also regulated by target of rapamycin (TOR, discussed further below), is involved in the control of gene regulation during stationary phase and activates IME1 expression by an unknown mechanism [18,19]. Rim15 phosphorylates the Igo1 and Igo2 proteins, which prevent specific mRNAs from degradation during stationary phase [20]. Perhaps Rim15 indirectly controls IME1 mRNA stability. Rim15 also mediates the interaction between Ime1 and Ume6 (discussed later) to activate early meiotic gene expression [18,21].

The PKA pathway is not the only regulator of IME1 expression in response to glucose. Snf1, the AMP kinase of budding yeast, is activated in response to low glucose levels (reviewed in Hedbacker & Carlson [22]). Snf1 regulates the expression of genes involved in alternative carbon source utilization, respiration, glycogen accumulation and thermotolerance. One transcriptional repressor inhibited by Snf1 phosphorylation is Mig1 [23,24]. In the presence of high glucose, Mig1 together with the co-repressor complex, Tup1–Ssn6, inhibits transcription of genes required for energy production, such as alternative carbon source utilization and respiration [23,25]. Interestingly, IME1 is also a target of this transcription repressor complex (figure 1). In the presence of glucose, Tup1–Ssn6 represses IME1 expression by binding at two sites in the IME1 promoter [26].

Whether PKA and Snf1 are the only mediators of carbon source signals at the IME1 promoter remains to be determined. Some studies have implicated the IME1 promoter to be responsive in the presence of a non-fermentable carbon source [15,27], but the mechanisms that underlie this regulation remain to be elucidated.

6. Tor controls IME1 expression

Nitrogen starvation is required for IME1 activation. How the nitrogen starvation signal is conveyed to the IME1 promoter is not well understood. A highly conserved signalling pathway known as the TOR pathway has been implicated in regulating cell growth in response to nutritional signals, among them nitrogen. In budding yeast, the TOR pathway promotes cell growth by stimulating multiple processes including transcription, translation and nutrient uptake. TOR is a protein kinase and budding yeast harbours two TOR genes, TOR1 and TOR2. Tor kinases form two distinct complexes. TOR-complex 1 (TORC1) is primarily involved in nutrient signalling and TOR-complex 2 (TORC2) regulates the actin cytoskeleton (reviewed in Wullschleger et al. [28]). When TOR signalling is inhibited, a starvation response ensues. TOR signalling also appears to inhibit sporulation. Treatment of cells with rapamycin, a chemical inhibitor of TORC1, leads to the induction of IME1 and sporulation regardless of the nutritional condition (figure 1) [29,30].

How TORC1 is activated by nutrient signals such as the presence of a nitrogen source is not understood, but effectors of the pathway have been identified. Among them are several transcription factors that regulate stress-response genes or genes regulated by nutritional starvation. The nitrogen catabolite repression transcription factors, also known as GATA factors, Gln3 and Gat1 are sequestered outside the nucleus by cytoplasmic protein Ure2, but upon nitrogen starvation Gat1 and Gln3 translocate into the nucleus [31–33]. During nitrogen starvation, pools of the phosphatases Sit4 and PP2A, which associate with the TORC1 target Tap42 in nutritional-rich growth conditions, are released from Tap42, which activates the phosphatases [34]. This is thought to stimulate dephosphorylation and disassociation of Ure2 from Gln3 and Gln3 translocation into the nucleus [31,35]. Msn2 and 4 are also regulated by TOR, and so is the transcription factor Sfp1 that regulates ribosome biogenesis genes [31,36]. Finally, under nutrient-poor conditions, TOR promotes the accumulation of the Rtg1 and Rtg3 transcription factors in the nucleus [32,37].

Are any of the TOR effectors IME1 regulators? Potential binding sites for Gln3/Gat1 and Rtg1/3 are found in the IME1 promoter. Msn2/4 is known to be recruited to the IME1 promoter. It is tempting to speculate that all of these or a subset of these transcription factors modulate IME1 expression in response to TOR signalling.

7. Cln–CDKs inhibit IME1

Cln–CDKs not only promote budding and hence vegetative growth, but they also actively interfere with entry into the sporulation programme. Cln–CDKs inhibit IME1 expression. Over-expression of Cln1, Cln2 or Cln3 in nutrient-starved conditions prevents sporulation and stimulates budding [38]. Furthermore, Cln overexpression represses IME1 transcription and causes translocation of the remaining Ime1 protein from the nucleus into the cytoplasm [38]. In addition, the transcription repressor Xbp1, which is induced during sporulation, reduces the transcription of CLN1 to stimulate sporulation [39]. The mutually antagonistic relationship between G1 cyclins and IME1 is a key aspect of the decision between vegetative growth and sporulation.

8. Respiration is required for entry into the sporulation programme

Cells can only sporulate in the absence of a fermentable carbon source, but a non-fermentable carbon source must also be present to provide the energy necessary to undergo the meiotic divisions and to form four spores. Utilization of a non-fermentable carbon source requires that yeast cells respire to produce energy. It is thus perhaps not surprising that cells with impaired respiratory abilities fail to form spores [27,29]. However, IME1 expression is completely repressed in respiratory-deficient mutants raising the possibility that additional control mechanisms rather than simple lack of energy are responsible for inhibiting IME1 expression when respiration is impaired (figure 1) [27,29]. The Rim101 transcription repressor, which is involved in pH response and cell wall construction, has been implicated in IME1 regulation [40,41]. Rim101 regulates the transcription of two transcriptional repressors, NRG1 and SMP1 [42]. Deletion of SMP1 can partly suppress the sporulation defects of a rim101 mutant [42]. In respiration-deficient cells, RIM101 expression is strongly reduced and could at least in part account for why IME1 is not transcribed in these cells [29]. Respiration also appears to be critical for induction of sporulation in fission yeast (see below) suggesting that communication between mitochondria and the nucleus is a fundamental aspect of gametogenesis. Understanding the relationship between gene expression and respiratory state will therefore be critical to determine how entry into gametogenesis is controlled.

9. RME1 represses IME1 expression in haploid cells

Haploid cells are of either the MATa or the MATα mating type and must not express IME1, as this is sufficient to induce sporulation. In both mating types, the DNA-binding protein Rme1 (repressor of IME1) prevents IME1 expression (figure 1). The IME1 promoter harbours two Rme1-binding sites and it is thought that binding of Rme1 to these sites inhibits IME1 expression [43–45]. Indeed, deletion of these RME1 binding sites will cause haploid cells to sporulate [44]. The mediator complex subunits Rgr1 and Sin4, global regulators of transcription and involved in chromatin organization, are required for the repression of IME1 by Rme1, suggesting that chromatin plays an important role in the repression mechanism [46–48].

Encoded at the MAT locus are DNA-binding proteins, a1 at the MATa locus and α2 at the MATα locus. When expressed together, the two proteins form a transcriptional repressor complex, a1–α2 that binds to the RME1 promoter and inhibits RME1 expression. Thus, RME1 inhibition of IME1 expression is alleviated in MATa/MATα diploid cells and the sporulation programme can be set in motion provided that appropriate nutritional cues are present.

10. Other factors controlling entry into sporulation

IME1 is not only regulated at the level of transcription, but multiple post-transcriptional mechanisms also ensure that Ime1 protein is produced in the right cell type and in response to the appropriate cues. There is some evidence to indicate that IME1 RNA, protein stability, protein localization and activity are also regulated.

Entry into the sporulation programme in some but not all genetic backgrounds depends on an N6-methyladenosine mRNA methyltransferase called Ime4 [49]. Substrates of Ime4 are the IME1, IME2 and IME4 mRNAs [50]. We do not yet know how Ime4 methylation affects these transcripts, but in the absence of IME4 entry into the sporulation programme is delayed or does not occur at all depending on the strain back-ground [40,49,51]. IME4 transcription is regulated in a manner highly similar to that of IME1. The IME4 promoter responds to the same nutritional cues as the IME1 promoter [49]. IME4 is also only expressed in diploid cells, and repressed in haploids. However, this inhibition in haploids is not brought about by RME1, but by an unusual mechanism involving the expression of an antisense RNA. In haploids, an antisense transcript (recently named RME2; [52]) is initiated from the 3′ end of IME4 to repress IME4 transcription [51]. In diploid cells, this antisense transcript is repressed by the a1–α2 repressor [51].

Ime1 stability and protein localization are also regulated. Little is known about these controls, but the protein kinase Ime2 is required for destabilizing Ime1 protein once cells have entered the sporulation programme [53]. Subcellular localization of Ime1 appears to be governed by nutritional cues. When TOR signalling is re-activated by switching cells to a preferred nitrogen source, Ime1 translocates from the nucleus into the cytoplasm [54]. Finally, Ime1 collaborates with another transcriptional regulator, Ume6, to regulate early gene expression during sporulation. In vegetatively growing cells, Ume6 acts as repressor by recruiting the Sin3 co-repressor and Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex to the promoters of early meiotic genes [21,55]. Upon nitrogen starvation, Ume6 transforms into an activator, and is essential for the induction of early meiotic genes [56]. Through a direct interaction Ume6 recruits Ime1 to early gene promoters, upon which Ume6 is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation to activate gene expression [57]. The switch from activator to repressor function of Ume6 is under nutritional control and involves the kinase activities of PKA and Rim15 [21,57].

Ime1 is the master regulator of entry into gametogenesis in budding yeast. Understanding the regulatory mechanisms which ensure that the transcription factor is active in the right cell type and responds to certain extracellular cues is essential, and much needs to be learned about the details of this control. Is initiation of gametogenesis wired similarly in other eukaryotes in the sense that multiple signals converge on a single factor, which then triggers gametogenesis or not? In what follows, we will summarize how entry into gametogenesis is controlled in fission yeast, highlighting remarkable parallels in the logic of cell-fate determination in the two yeasts.

11. Initiation of sporulation in schizosaccharomyces pombe

Schizosaccharomyces pombe and S. cerevisiae diverged approximately 330–420 million years ago. The two ascomycete fungi are thus evolutionarily highly divergent from each other [58]. Despite this divergence, many of the signals and pathways shown to be important for entry into the sporulation programme in budding yeast are also operative in fission yeast.

The vegetative state in S. pombe is haploid. Fission yeast cells do mate to form diploids, but this state is transient. Concomitant with the mating programme, fission yeast cells initiate the sporulation programme to undergo meiosis, once a diploid has been produced, and form four haploid spores. Thus, in fission yeast, a concerted mating—sporulation programme is initiated when nutrients are limiting. In response to nitrogen starvation, haploid fission yeast cells arrest in G1 and cells of opposite mating type, h+ and h−, undergo conjugation. The resulting zygote undergoes meiosis and forms four haploid spores.

The proteins that regulate the initiation to gamete formation are not conserved between budding and fission yeast. Ime1 is not present in S. pombe, but analogously to budding yeast a master transcription factor, Ste11, determines whether cells enter the sporulation programme. As conjugation is tightly coupled with sporulation, it is not surprising that Ste11 also regulates mating.

12. Ste11: master regulator of sexual differentiation and sporulation in schizosaccharomyces pombe

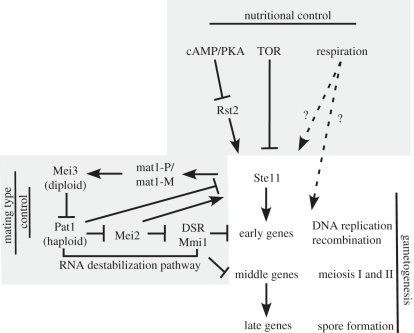

As in the case of IME1 in budding yeast, multiple external signals converge on the ste11+ promoter (figure 2). Entry into gametogenesis in S. pombe requires a nitrogen starvation response, and glucose has an inhibitory effect on the expression of genes important for meiosis and sporulation. These nutritional signals control ste11+ expression. When ste11+ is expressed from a constitutive promoter, cells mate and sporulate even in the presence of ample nitrogen [59]. When activated, ste11+ induces the transcription of genes required for mating and the early stages of sporulation. Furthermore, ste11+ also indirectly conveys mating-type control into sporulation. Finally, as in budding yeast, respiratory activity is also essential for sporulation [29]. However, mating does not appear to be affected indicating that this signal does not operate on the ste11+ promoter. In what follows, we will describe how ste11+ expression is controlled by various nutrient sensing pathways.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the signals controlling entry into sporulation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nutritional signals converge at the ste11+ promoter. Subsequently, Ste11 induces mating and sporulation. See text for details.

13. The protein kinase a pathway represses ste11+ transcription

Glucose also regulates the PKA pathway in fission yeast. Mutations that lead to constitutively active PKA activity or addition of cAMP to the growth medium prevent the initiation of sporulation. Conversely, low levels of PKA activity promote sexual development and subsequent sporulation irrespective of nutritional conditions. ste11+ transcription mirrors this response to PKA pathway activity. Loss of PKA activity brought about by deleting pka1+ (encoding the catalytic subunit of PKA) or cyr1+ (encoding adenylate cyclase) results in constitutive expression of ste11+, whereas a deletion of the gene encoding the inhibitory subunit of PKA, cgs1+, represses ste11+ transcription [60,61].

PKA regulates the transcription factor Rst2. Phosphorylation of Rst2 by PKA causes this zinc finger transcription factor to localize to the cytoplasm where it is kept inactivate [62,63] (figure 2). When glucose levels are low, Rst2 translocates into the nucleus and binds a stress-response DNA element in the ste11+ promoter to stimulate transcription [63]. Interestingly, Rst2 has a similar type of zinc finger motif as budding yeast Msn2, which activates IME1 (see previous section), indicating that activation of IME1 and ste11+ by the PKA pathway is a conserved feature of spore development in the two fungi [62].

14. Tor signalling represses ste11+

As in budding yeast, TOR signalling controls sporulation. Inactivation of TOR signalling through the use of a temperature-sensitive tor2+ allele showed that loss of TOR signalling causes a G1 arrest, and initiates sexual differentiation and subsequently sporulation [64,65] (figure 2). Accordingly, tor2+ inactivation also results in transcription of ste11+. Although it is clear that TOR signalling is a key regulator of gametogenesis, it is not known how TOR signalling causes the repression of ste11+. Unlike in budding yeast, transcriptional regulators controlled by TOR activity await identification.

It should be noted that TOR signalling not only regulates ste11+ transcription, but also Ste11 activity. Tor2 interacts with Ste11 and Mei2, a factor critical for entry into sporulation described below, to inhibit their cellular function [65]. Furthermore, PKA and TOR act together to regulate Ste11 localization and control Ste11-dependent transcription [66]. Thus, TOR signalling affects ste11+ in multiple ways to ensure that mating and sporulation do not occur under nutrient-rich conditions.

15. Respiration is required for sporulation in schizosaccharomyces pombe

Unlike S. cerevisiae, S. pombe was initially described as a ‘petite negative’ strain, requiring mitochondrial activity for survival [67]. Subsequently, fission yeast cells lacking mitochondrial DNA, which causes respiration failure, have been isolated, but these mutants require a nuclear mutation for survival [68]. These second-site suppressor mutations allowed researchers to ask whether respiration was required for mating and/or sporulation. Defects in respiration do not appear to interfere with mating, but respiration defective fission yeast cells fail to form spores [29]. We do not yet know which aspect of gametogenesis requires respiration, but it is clear that in fission yeast, it is not an indirect consequence of a lack of energy as could be argued in budding yeast because S. pombe cells can sporulate in the presence of a fermentable carbon source. Thus, energy generation should occur even in the absence of respiration. Understanding the respiratory requirement for sporulation initiation may thus be best examined in fission yeast.

16. Mating-type control of sporulation: Pat1 kinase prevents haploid sporulation in schizosaccharomyces pombe

Haploid fission yeast cells, like haploid budding yeast cells, do not initiate meiosis and sporulation. In both species, sporulation is repressed in cells harbouring only one of the two mating types. The molecular mechanism of repression of sporulation in haploid fission yeast cells differs from the mechanism in S. cerevisiae, perhaps because mating and sporulation are coupled.

In haploid cells of S. pombe, entry into the sporulation programme is repressed by a protein kinase called Pat1 [69,70] (figure 2). Pat1 represses the activity of two early sporulation proteins. First, Pat1 phosphorylates Ste11. This causes binding to the 14-3-3 protein Rad24, and inhibition of Ste11′s transcriptional activity [69,70]. Secondly, Pat1 phosphorylates an RNA-binding protein known as Mei2 that is essential for the early stages of sporulation including the initiation of pre-meiotic DNA synthesis [71,72] (figure 2). Phosphorylation of Mei2 by Pat1 targets the protein for ubiquitin-mediated degradation [70]. A Mei2 mutant refractory to Pat1 phosphorylation causes haploid cells to undergo a fatal meiosis [72].

How does Mei2 promote entry into the sporulation programme? Mei2 regulates an RNA degradation system known as the determinant of selective removal (DSR)–Mmi1 system that selectively removes sporulation-specific transcripts [73] (figure 2). Mmi1 is an RNA-binding protein of the YT521-B homology (YTH) family and binds to early and middle meiotic transcripts that contain an element in their 3′ UTRs. Subsequently, Mmi1 interacts with Pab1, a polyA-binding protein, and the exosome, a protein complex involved in RNA degradation, to degrade meiotic mRNAs [73–75]. Mei2 inhibits the DSR–Mmi1 by binding to Mmi1. The interaction between the two proteins can be seen as a dot-like structure in the nucleus [73]. The polyadenylated meiRNA, encoded by the sme2+ locus, is also found in this focus and interacts with Mei2 and is required for Mei2–Mmi1 nuclear localization [71,73,76]. However, the role of meiRNA in the Mei2–Mmi1 complex is not understood.

In diploid cells, Pat1 must be inactivated for Mei2 to bind to and inhibit the DSR–Mmi1. Ste11 brings about this inhibition, albeit indirectly (figure 2). As part of Ste11's role in mating, the transcription factor induces expression of the mat1-locus-induced genes, mat1-Mc/mat1-Mm (in h− cells) and mat1-Pc/mat1-Pm (in h+ cells) [59]. In diploid cells, mat1-Pc and mat1-Mc are induced first to generate a pheromone signal and to activate transcription of mat1-Pm and mat1-Mm, which are required for sporulation [77]. The Mat1-Pm, a homeodomain protein, and Mat1-Mc, a high mobility group (HMG) box protein, synergistically activate the transcription of the mei3+ gene [77–79] (figure 2). Mei3 inhibits Pat1 kinase activity. The protein acts as a pseudosubstrate preventing the protein kinase from phosphorylating other substrates [69]. When mei3+ is ectopically expressed in haploid cells, they will enter a lethal meiosis [80].

The ste11+ promoter, like the IME1 promoter, integrates nutritional signals to induce the mating–sporulation programme. In contrast to IME1 however, its transcription is not controlled by mating type but, instead, Ste11 is required to establish mating-type control over sporulation. These differences in wiring probably reflect differences in lifestyle. Mating and sporulation are uncoupled in budding yeast, whereas the two events are tightly coupled in fission yeast. This coupling is facilitated by ste11+. Thus, ste11+ must be active in both haploid and diploid cells, which necessitates loss of mating-type control on ste11+ expression.

17. Gametogenesis in mammals

In higher eukaryotes, germ cells, the cells that will eventually undergo gametogenesis to form sperm or egg, are specified very early during embryogenesis. In the Drosophila embryo, for example in nuclei in the vicinity of polar granules, protein–RNA complexes that specify germ cell fate will cellularize first to form pole cells, the future germ cells [81]. In the mouse, a small number of pluripotent epiblast cells gives rise to the germ cells. Once specified, these primordial germ cells (PGCs) migrate into the gonad where they will develop into cells capable of undergoing meiosis and gamete formation. Many of the genes involved in determining germ cell fate and their migration into the gonad have been identified in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. We direct the reader to several excellent reviews that discuss these topics [82,83]. Instead, here, we will focus on describing recent advances in our understanding how PGCs develop into gametogenesis competent cells and how entry into the meiotic divisions is controlled in the mouse. We will also highlight parallels between mouse and budding and fission yeast.

In mammals, PGCs are specified during early embryogenesis. They migrate into the gonad during day 10.5–11.5 of embryonic development. The fate of male and female PGCs diverges after their arrival in the somatic gonad. Female PGCs will differentiate into oogonia that undergo mitotic divisions to increase cell number, and then enter gametogenesis. By day 13.5 of embryonic development, chromosome condensation indicative of meiotic prophase is observed. In males, PGCs will remain arrested in G0 and only enter gametogenesis after birth.

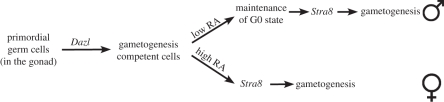

The putative transcription factor Stra8 could be viewed as the functional counterpart of IME1 and ste11+ in mammals (figure 3) [86]. It is essential for gamete formation in males and females. Mice-lacking Stra8 do not enter meiosis and gametogenesis [87,88]. Importantly, Stra8 expression appears to function as an integrator of internal and external cues to induce gametogenesis. Cell intrinsic cues are mediated by Dazl and pluripotency factors. Stra8 is repressed by the pluripotency factor and RNA-binding protein NANOS2 and requires Dazl for expression [89]. Dazl, for Deleted in azoospermia-like, is the mouse homologue of the human Y-chromosome-encoded DAZ gene, which was first identified as deleted in patients with azoospermia [90]. Dazl is expressed in post-migratory PGCs of both sexes and, unlike human DAZ, is essential for gametogenesis in both sexes. In its absence neither female nor male PGCs show any sign of entry into the meiotic programme or gametogenesis [84]. Proteins specific for the meiotic divisions, such as REC8 and SYCP3, which are produced during the mitotic divisions preceding entry into the germ cell fate, do not associate with chromosomes in Dazl null mice, indicating that entry into the meiotic programme and hence gametogenesis does not occur [84]. Instead, germ cells of Dazl-deficient mice retain an undifferentiated PGC-like state with the expression levels of pluripotency factors such as Oct4, Nanog and Sox2 remaining high [85]. These results indicate that Dazl is essential for committing PGCs to gametogenesis. The protein sets in motion a developmental programme that downregulates pluripotency factors and induces gametogenesis in females and G0 arrest in males (figure 3). How Dazl commits PGCs to gametogenesis is not known. The protein encodes an RNA-binding protein. Perhaps, as in fission yeast, an RNA stability regulatory mechanism is important for gametogenesis in mammals.

Figure 3.

Schematic of how germ cell fate is established in mice. Cell intrinsic (DAZL activity) and extrinsic (RA) signals converge to regulate Stra8 expression. Adapted from [84,85]. See text for details.

Stra8 is also regulated by signals generated by the somatic gonad. Stra8 transcription is induced by retinoic acid (RA), which activates the retinoic acid receptors (RARs α, β and γ) and X (RXR α, β and γ; figure 3). In fact Stra8 stands for stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8. In embryonic ovaries, RA induces Stra8 expression in an anterior–posterior manner [91]. This RA response of Stra8 expression can be recapitulated in vitro. Local injection of RA is sufficient to induce Stra8 expression in cultured embryonic ovaries [88,92]. In the embryonic testis, RA levels are low and as a result Stra8 is not expressed [92]. It has been suggested that RA levels are kept low by CYP26B, an enzyme that is expressed in the somatic testes and oxidizes RA into non-active polar metabolites such as 4-oxo-RA [93]. Stra8 expression is induced in the testes later in development, at day 10 postpartum and then induces meiosis and spermatogenesis [94]. The sexually dimorphic regulation of Stra8 by extrinsic signals explains why entry into gametogenesis occurs during embryogenesis in females and postpartum in males.

How Stra8 induces entry into pre-meiotic S phase and triggers gametogenesis is not yet understood. The protein localizes to the nucleus and cytoplasm and harbours transcriptional activity [86]. It will be interesting to determine whether Stra8, like IME1 and ste11+, regulates transcription of genes critical for meiotic chromosome morphogenesis and homologous recombination, one of the earliest events of gametogenesis.

18. Concluding remarks

At first glance, the mechanisms underlying gametogenesis appear quite diverse between budding yeast, fission yeast and mammals. However, some striking similarities exist. In all three species, a master regulator is essential for the entry into gametogenesis: IME1 in budding yeast, ste11+ in fission yeast and Stra8 in mice. Cell intrinsic and extrinsic signals converge at their promoters to regulate their expression. Cell intrinsic signals such as mating-type information and respiration in the yeasts and germ cell-specific expression of Dazl in the mouse create a gametogenesis competency state on which extracellular signals act to induce gamete formation. In S. pombe and S. cerevisiae, these extracellular signals are nutritional signals that function through highly conserved pathways—the PKA and the TOR pathways—to induce sporulation. It will be interesting to determine whether the two pathways also regulate entry into gametogenesis in mammals. Downregulation of PKA activity is required during oocyte maturation [95,96], and perhaps it is also needed during entry into gametogenesis. A recent study showed that downregulation of mTORC1 is important for maintenance of the spermatogonial progenitor cells population [97]. Perhaps reduced mTOR activity is also needed for initiation of gametogenesis.

The involvement of nutrient-sensing pathways in controlling gametogenesis in mammals or higher eukaryotes, in general, is speculation. However, another signal critical for entry into the sporulation programme in both fission and budding yeast—respiration—could very well play an important role in mammalian gametogenesis. Defects in mitochondrial function correlate with female infertility in humans [98]. In addition, mutations in mitochondrial DNA affecting respiratory activity in the female mouse germline are selectively removed within four generations, suggesting that functional mitochondria are required for oogenesis [99]. Exploring the importance of the pathways governing gametogenesis identified in yeasts could—as it has done in many instances previously—provide important clues as to how gametogenesis is controlled in humans.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Alexi Goranov, Elçin Ünal and Yoshinori Watanabe for their critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by a grant GM62207 from the NIH and a Rubicon grant (825.09.004) from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research to F.W. A.A. is also an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Kassir Y., Granot D., Simchen G. 1988. IME1, a positive regulator gene of meiosis in S. cerevisiae. Cell 52, 853–862 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90427-8 (doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90427-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin K. R., Zhang C., Shokat K. M., Herskowitz I. 2003. Control of landmark events in meiosis by the CDK Cdc28 and the meiosis-specific kinase Ime2. Genes Dev. 17, 1524–1539 10.1101/gad.1101503 (doi:10.1101/gad.1101503) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pak J., Segall J. 2002. Regulation of the premiddle and middle phases of expression of the NDT80 gene during sporulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6417–6429 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6417-6429.2002 (doi:10.1128/MCB.22.18.6417-6429.2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith H. E., Su S. S., Neigeborn L., Driscoll S. E., Mitchell A. P. 1990. Role of IME1 expression in regulation of meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 6103–6113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primig M., Williams R. M., Winzeler E. A., Tevzadze G. G., Conway A. R., Hwang S. Y., Davis R. W., Esposito R. E. 2000. The core meiotic transcriptome in budding yeasts. Nat. Genet. 26, 415–423 10.1038/82539 (doi:10.1038/82539) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu S., Herskowitz I. 1998. Gametogenesis in yeast is regulated by a transcriptional cascade dependent on Ndt80. Mol. Cell 1, 685–696 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80068-4 (doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80068-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dirick L., Goetsch L., Ammerer G., Byers B. 1998. Regulation of meiotic S phase by Ime2 and a Clb5,6-associated kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 281, 1854–1857 10.1126/science.281.5384.1854 (doi:10.1126/science.281.5384.1854) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell A. P., Driscoll S. E., Smith H. E. 1990. Positive control of sporulation-specific genes by the IME1 and IME2 products in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 2104–2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith H. E., Mitchell A. P. 1989. A transcriptional cascade governs entry into meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 2142–2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell A. P., Bowdish K. S. 1992. Selection for early meiotic mutants in yeast. Genetics 131, 65–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuura A., Treinin M., Mitsuzawa H., Kassir Y., Uno I., Simchen G. 1990. The adenylate cyclase/protein kinase cascade regulates entry into meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through the gene IME1. Embo. J. 9, 3225–3232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith A., Ward M. P., Garrett S. 1998. Yeast PKA represses Msn2p/Msn4p-dependent gene expression to regulate growth, stress response and glycogen accumulation. Embo J. 17, 3556–3564 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3556 (doi:10.1093/emboj/17.13.3556) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorner W., Durchschlag E., Martinez-Pastor M. T., Estruch F., Ammerer G., Hamilton B., Ruis H., Schuller C. 1998. Nuclear localization of the C2H2 zinc finger protein Msn2p is regulated by stress and protein kinase A activity. Genes Dev. 12, 586–597 10.1101/gad.12.4.586 (doi:10.1101/gad.12.4.586) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez-Pastor M. T., Marchler G., Schuller C., Marchler-Bauer A., Ruis H., Estruch F. 1996. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae zinc finger proteins Msn2p and Msn4p are required for transcriptional induction through the stress response element (STRE). Embo J. 15, 2227–2235 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sagee S., Sherman A., Shenhar G., Robzyk K., Ben-Doy N., Simchen G., Kassir Y. 1998. Multiple and distinct activation and repression sequences mediate the regulated transcription of IME1, a transcriptional activator of meiosis-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 1985–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shenhar G., Kassir Y. 2001. A positive regulator of mitosis, Sok2, functions as a negative regulator of meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1603–1612 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1603-1612.2001 (doi:10.1128/MCB.21.5.1603-1612.2001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward M. P., Gimeno C. J., Fink G. R., Garrett S. 1995. SOK2 may regulate cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase-stimulated growth and pseudohyphal development by repressing transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 6854–6863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vidan S., Mitchell A. P. 1997. Stimulation of yeast meiotic gene expression by the glucose-repressible protein kinase Rim15p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 2688–2697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swinnen E., Wanke V., Roosen J., Smets B., Dubouloz F., Pedruzzi I., Cameroni E., De Virgilio C., Winderickx J. 2006. Rim15 and the crossroads of nutrient signalling pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Div. 1, 3. 10.1186/1747-1028-1-3 (doi:10.1186/1747-1028-1-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talarek N., et al. 2010. Initiation of the TORC1-regulated G0 program requires Igo1/2, which license specific mRNAs to evade degradation via the 5′-3′ mRNA decay pathway. Mol. Cell 38, 345–355 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.039 (doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.039) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pnueli L., Edry I., Cohen M., Kassir Y. 2004. Glucose and nitrogen regulate the switch from histone deacetylation to acetylation for expression of early meiosis-specific genes in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5197–5208 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5197-5208.2004 (doi:10.1128/MCB.24.12.5197-5208.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedbacker K., Carlson M. 2008. SNF1/AMPK pathways in yeast. Front. Biosci. 13, 2408–2420 10.2741/2854 (doi:10.2741/2854) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papamichos-Chronakis M., Gligoris T., Tzamarias D. 2004. The Snf1 kinase controls glucose repression in yeast by modulating interactions between the Mig1 repressor and the Cyc8-Tup1 co-repressor. EMBO Rep. 5, 368–372 10.1038/sj.embor.7400120 (doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400120) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treitel M. A., Kuchin S., Carlson M. 1998. Snf1 protein kinase regulates phosphorylation of the Mig1 repressor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 6273–6280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treitel M. A., Carlson M. 1995. Repression by SSN6-TUP1 is directed by MIG1, a repressor/activator protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 3132–3136 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3132 (doi:10.1073/pnas.92.8.3132) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizuno T., Nakazawa N., Remgsamrarn P., Kunoh T., Oshima Y., Harashima S. 1998. The Tup1-Ssn6 general repressor is involved in repression of IME1 encoding a transcriptional activator of meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 33, 239–247 10.1007/s002940050332 (doi:10.1007/s002940050332) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treinin M., Simchen G. 1993. Mitochondrial activity is required for the expression of IME1, a regulator of meiosis in yeast. Curr. Genet. 23, 223–227 10.1007/BF00351500 (doi:10.1007/BF00351500) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N. 2006. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124, 471–484 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jambhekar A., Amon A. 2008. Control of meiosis by respiration. Curr. Biol. 18, 969–975 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.047 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.047) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng X. F., Schreiber S. L. 1997. Target of rapamycin proteins and their kinase activities are required for meiosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 3070–3075 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3070 (doi:10.1073/pnas.94.7.3070) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck T., Hall M. N. 1999. The TOR signalling pathway controls nuclear localization of nutrient-regulated transcription factors. Nature 402, 689–692 10.1038/45287 (doi:10.1038/45287) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crespo J. L., Powers T., Fowler B., Hall M. N. 2002. The TOR-controlled transcription activators GLN3, RTG1, and RTG3 are regulated in response to intracellular levels of glutamine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6784–6789 10.1073/pnas.102687599 (doi:10.1073/pnas.102687599) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuruvilla F. G., Shamji A. F., Schreiber S. L. 2001. Carbon- and nitrogen-quality signaling to translation are mediated by distinct GATA-type transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7283–7288 10.1073/pnas.121186898 (doi:10.1073/pnas.121186898) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Como C. J., Arndt K. T. 1996. Nutrients, via the Tor proteins, stimulate the association of Tap42 with type 2A phosphatases. Genes Dev. 10, 1904–1916 10.1101/gad.10.15.1904 (doi:10.1101/gad.10.15.1904) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tate J. J., Georis I., Dubois E., Cooper T. G. 2010. Distinct phosphatase requirements and GATA factor responses to nitrogen catabolite repression and rapamycin treatment in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17 880–17 895 10.1074/jbc.M109.085712 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.085712) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marion R. M., Regev A., Segal E., Barash Y., Koller D., Friedman N., O'Shea E. K. 2004. Sfp1 is a stress- and nutrient-sensitive regulator of ribosomal protein gene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 14 315–14 322 10.1073/pnas.0405353101 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0405353101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komeili A., Wedaman K. P., O'Shea E. K., Powers T. 2000. Mechanism of metabolic control. Target of rapamycin signaling links nitrogen quality to the activity of the Rtg1 and Rtg3 transcription factors. J. Cell Biol. 151, 863–878 10.1083/jcb.151.4.863 (doi:10.1083/jcb.151.4.863) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colomina N., Gari E., Gallego C., Herrero E., Aldea M. 1999. G1 cyclins block the Ime1 pathway to make mitosis and meiosis incompatible in budding yeast. Embo J. 18, 320–329 10.1093/emboj/18.2.320 (doi:10.1093/emboj/18.2.320) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mai B., Breeden L. 2000. CLN1 and its repression by Xbp1 are important for efficient sporulation in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 478–487 10.1128/MCB.20.2.478-487.2000 (doi:10.1128/MCB.20.2.478-487.2000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su S. S., Mitchell A. P. 1993. Molecular characterization of the yeast meiotic regulatory gene RIM1. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 3789–3797 10.1093/nar/21.16.3789 (doi:10.1093/nar/21.16.3789) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li W., Mitchell A. P. 1997. Proteolytic activation of Rim1p, a positive regulator of yeast sporulation and invasive growth. Genetics 145, 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamb T. M., Mitchell A. P. 2003. The transcription factor Rim101p governs ion tolerance and cell differentiation by direct repression of the regulatory genes NRG1 and SMP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 677–686 10.1128/MCB.23.2.677-686.2003 (doi:10.1128/MCB.23.2.677-686.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Covitz P. A., Herskowitz I., Mitchell A. P. 1991. The yeast RME1 gene encodes a putative zinc finger protein that is directly repressed by a1-alpha 2. Genes Dev. 5, 1982–1989 10.1101/gad.5.11.1982 (doi:10.1101/gad.5.11.1982) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Covitz P. A., Mitchell A. P. 1993. Repression by the yeast meiotic inhibitor RME1. Genes Dev. 7, 1598–1608 10.1101/gad.7.8.1598 (doi:10.1101/gad.7.8.1598) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimizu M., Li W., Covitz P. A., Hara M., Shindo H., Mitchell A. P. 1998. Genomic footprinting of the yeast zinc finger protein Rme1p and its roles in repression of the meiotic activator IME1. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 2329–2336 10.1093/nar/26.10.2329 (doi:10.1093/nar/26.10.2329) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang Y. W., Dohrmann P. R., Stillman D. J. 1995. Genetic and physical interactions between yeast RGR1 and SIN4 in chromatin organization and transcriptional regulation. Genetics 140, 47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y., Bjorklund S., Jiang Y. W., Kim Y. J., Lane W. S., Stillman D. J., Kornberg R. D. 1995. Yeast global transcriptional regulators Sin4 and Rgr1 are components of mediator complex/RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 10 864–10 868 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10864 (doi:10.1073/pnas.92.24.10864) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Covitz P. A., Song W., Mitchell A. P. 1994. Requirement for RGR1 and SIN4 in RME1-dependent repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 138, 577–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shah J. C., Clancy M. J. 1992. IME4, a gene that mediates MAT and nutritional control of meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 1078–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bodi Z., Button J. D., Grierson D., Fray R. G. 2010. Yeast targets for mRNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 5327–5335 10.1093/nar/gkq266 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkq266) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hongay C. F., Grisafi P. L., Galitski T., Fink G. R. 2006. Antisense transcription controls cell fate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 127, 735–745 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.038 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gelfand B., Mead J., Bruning A., Apostolopoulos N., Tadigotla V., Nagaraj V., Sengupta A. M., Vershon A. K. 2011. Regulated antisense transcription controls expression of cell-type specific genes in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1701–1709 10.1128/MCB.01071-10 (doi:10.1128/MCB.01071-10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guttmann-Raviv N., Martin S., Kassir Y. 2002. Ime2, a meiosis-specific kinase in yeast, is required for destabilization of its transcriptional activator, Ime1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 2047–2056 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2047-2056.2002 (doi:10.1128/MCB.22.7.2047-2056.2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colomina N., Liu Y., Aldea M., Gari E. 2003. TOR regulates the subcellular localization of Ime1, a transcriptional activator of meiotic development in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 7415–7424 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7415-7424.2003 (doi:10.1128/MCB.23.20.7415-7424.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inai T., Yukawa M., Tsuchiya E. 2007. Interplay between chromatin and trans-acting factors on the IME2 promoter upon induction of the gene at the onset of meiosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 1254–1263 10.1128/MCB.01661-06 (doi:10.1128/MCB.01661-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Washburn B. K., Esposito R. E. 2001. Identification of the Sin3-binding site in Ume6 defines a two-step process for conversion of Ume6 from a transcriptional repressor to an activator in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2057–2069 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2057-2069.2001 (doi:10.1128/MCB.21.6.2057-2069.2001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mallory M. J., Cooper K. F., Strich R. 2007. Meiosis-specific destruction of the Ume6p repressor by the Cdc20-directed APC/C. Mol. Cell. 27, 951–961 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.019 (doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sipiczki M. 2000. Where does fission yeast sit on the tree of life? Genome Biol. 1, REVIEWS1011. 10.1186/gb-2000-1-2-reviews1011 (doi:10.1186/gb-2000-1-2-reviews1011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sugimoto A., Iino Y., Maeda T., Watanabe Y., Yamamoto M. 1991. Schizosaccharomyces pombe ste11+encodes a transcription factor with an HMG motif that is a critical regulator of sexual development. Genes Dev. 5, 1990–1999 10.1101/gad.5.11.1990 (doi:10.1101/gad.5.11.1990) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maeda T., Mochizuki N., Yamamoto M. 1990. Adenylyl cyclase is dispensable for vegetative cell growth in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 87, 7814–7818 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7814 (doi:10.1073/pnas.87.20.7814) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maeda T., Watanabe Y., Kunitomo H., Yamamoto M. 1994. Cloning of the pka1 gene encoding the catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 9632–9637 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kunitomo H., Higuchi T., Iino Y., Yamamoto M. 2000. A zinc-finger protein, Rst2p, regulates transcription of the fission yeast ste11+gene, which encodes a pivotal transcription factor for sexual development. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 3205–3217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Higuchi T., Watanabe Y., Yamamoto M. 2002. Protein kinase A regulates sexual development and gluconeogenesis through phosphorylation of the Zn finger transcriptional activator Rst2p in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1–11 10.1128/MCB.22.1.1-11.2002 (doi:10.1128/MCB.22.1.1-11.2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsuo T., Otsubo Y., Urano J., Tamanoi F., Yamamoto M. 2007. Loss of the TOR kinase Tor2 mimics nitrogen starvation and activates the sexual development pathway in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3154–3164 10.1128/MCB.01039-06 (doi:10.1128/MCB.01039-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alvarez B., Moreno S. 2006. Fission yeast Tor2 promotes cell growth and represses cell differentiation. J. Cell. Sci. 119, 4475–4485 10.1242/jcs.03241 (doi:10.1242/jcs.03241) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valbuena N., Moreno S. 2010. TOR and PKA pathways synergize at the level of the Ste11 transcription factor to prevent mating and meiosis in fission yeast. PLoS ONE 5, e11514. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011514 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011514) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heslot H., Goffeau A., Louis C. 1970. Respiratory metabolism of a ‘petite negative’ yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe 972h. J. Bacteriol. 104, 473–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haffter P., Fox T. D. 1992. Nuclear mutations in the petite-negative yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe allow growth of cells lacking mitochondrial DNA. Genetics 131, 255–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li P., McLeod M. 1996. Molecular mimicry in development: identification of ste11+ as a substrate and mei3+ as a pseudosubstrate inhibitor of ran1+ kinase. Cell 87, 869–880 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81994-7 (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81994-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kitamura K., Katayama S., Dhut S., Sato M., Watanabe Y., Yamamoto M., Toda T. 2001. Phosphorylation of Mei2 and Ste11 by Pat1 kinase inhibits sexual differentiation via ubiquitin proteolysis and 14-3-3 protein in fission yeast. Dev. Cell 1, 389–399 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00037-5 (doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00037-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watanabe Y., Yamamoto M. 1994. S. pombe mei2+ encodes an RNA-binding protein essential for premeiotic DNA synthesis and meiosis I, which cooperates with a novel RNA species meiRNA. Cell 78, 487–498 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90426-X (doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90426-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watanabe Y., Shinozaki-Yabana S., Chikashige Y., Hiraoka Y., Yamamoto M. 1997. Phosphorylation of RNA-binding protein controls cell cycle switch from mitotic to meiotic in fission yeast. Nature 386, 187–190 10.1038/386187a0 (doi:10.1038/386187a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harigaya Y., et al. 2006. Selective elimination of messenger RNA prevents an incidence of untimely meiosis. Nature 442, 45–50 10.1038/nature04881 (doi:10.1038/nature04881) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.St-Andre O., Lemieux C., Perreault A., Lackner D. H., Bahler J., Bachand F. 2010. Negative regulation of meiotic gene expression by the nuclear poly(a)-binding protein in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27 859–27 868 10.1074/jbc.M110.150748 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.150748) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamanaka S., Yamashita A., Harigaya Y., Iwata R., Yamamoto M. 2010. Importance of polyadenylation in the selective elimination of meiotic mRNAs in growing S. pombe cells. Embo J. 29, 2173–2181 10.1038/emboj.2010.108 (doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamashita A., Watanabe Y., Nukina N., Yamamoto M. 1998. RNA-assisted nuclear transport of the meiotic regulator Mei2p in fission yeast. Cell 95, 115–123 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81787-0 (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81787-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Willer M., Hoffmann L., Styrkarsdottir U., Egel R., Davey J., Nielsen O. 1995. Two-step activation of meiosis by the mat1 locus in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 4964–4970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van Heeckeren W. J., Dorris D. R., Struhl K. 1998. The mating-type proteins of fission yeast induce meiosis by directly activating mei3 transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 7317–7326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McLeod M., Stein M., Beach D. 1987. The product of the mei3+ gene, expressed under control of the mating-type locus, induces meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. Embo J. 6, 729–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang W., Li P., Schettino A., Peng Z., McLeod M. 1998. Characterization of functional regions in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe mei3 developmental activator. Genetics 150, 1007–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williamson A., Lehmann R. 1996. Germ cell development in Drosophila. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 12, 365–391 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.365 (doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.365) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Richardson B. E., Lehmann R. 2010. Mechanisms guiding primordial germ cell migration: strategies from different organisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 37–49 10.1038/nrm2815 (doi:10.1038/nrm2815) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kimble J., Crittenden S. L. 2005. Germline proliferation and its control. WormBook (eds The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook) (doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.13.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin Y., Gill M. E., Koubova J., Page D. C. 2008. Germ cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors govern meiotic initiation in mouse embryos. Science 322, 1685–1687 10.1126/science.1166340 (doi:10.1126/science.1166340) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gill M. E., Hu Y. C., Lin Y., Page D. C. 2011. Licensing of gametogenesis, dependent on RNA binding protein DAZL, as a gateway to sexual differentiation of fetal germ cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 7443–7448 10.1073/pnas.1104501108 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1104501108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tedesco M., La Sala G., Barbagallo F., De Felici M., Farini D. 2009. STRA8 shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm and displays transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35 781–35 793 10.1074/jbc.M109.056481 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.056481) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baltus A. E., Menke D. B., Hu Y. C., Goodheart M. L., Carpenter A. E., de Rooij D. G., Page D. C. 2006. In germ cells of mouse embryonic ovaries, the decision to enter meiosis precedes premeiotic DNA replication. Nat. Genet. 38, 1430–1434 10.1038/ng1919 (doi:10.1038/ng1919) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Anderson E. L., Baltus A. E., Roepers-Gajadien H. L., Hassold T. J., de Rooij D. G., van Pelt A. M., Page D. C. 2008. Stra8 and its inducer, retinoic acid, regulate meiotic initiation in both spermatogenesis and oogenesis in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14 976–14 980 10.1073/pnas.0807297105 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0807297105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Suzuki A., Saga Y. 2008. Nanos2 suppresses meiosis and promotes male germ cell differentiation. Genes Dev. 22, 430–435 10.1101/gad.1612708 (doi:10.1101/gad.1612708) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Saxena R., et al. 1996. The DAZ gene cluster on the human Y chromosome arose from an autosomal gene that was transposed, repeatedly amplified and pruned. Nat. Genet. 14, 292–299 10.1038/ng1196-292 (doi:10.1038/ng1196-292) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bowles J., et al. 2006. Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science 312, 596–600 10.1126/science.1125691 (doi:10.1126/science.1125691) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Koubova J., Menke D. B., Zhou Q., Capel B., Griswold M. D., Page D. C. 2006. Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2474–2479 10.1073/pnas.0510813103 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0510813103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.White J. A., et al. 2000. Identification of the human cytochrome P450, P450RAI-2, which is predominantly expressed in the adult cerebellum and is responsible for all-trans-retinoic acid metabolism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6403–6408 10.1073/pnas.120161397 (doi:10.1073/pnas.120161397) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhou Q., Nie R., Li Y., Friel P., Mitchell D., Hess R. A., Small C., Griswold M. D. 2008. Expression of stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (Stra8) in spermatogenic cells induced by retinoic acid: an in vivo study in vitamin A-sufficient postnatal murine testes. Biol. Reprod. 79, 35–42 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066795 (doi:10.1095/biolreprod.107.066795) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bornslaeger E. A., Mattei P., Schultz R. M. 1986. Involvement of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and protein phosphorylation in regulation of mouse oocyte maturation. Dev. Biol. 114, 453–462 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90209-5 (doi:10.1016/0012-1606(86)90209-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dekel N., Beers W. H. 1978. Rat oocyte maturation in vitro: relief of cyclic AMP inhibition by gonadotropins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 75, 4369–4373 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4369 (doi:10.1073/pnas.75.9.4369) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hobbs R. M., Seandel M., Falciatori I., Rafii S., Pandolfi P. P. 2010. Plzf regulates germline progenitor self-renewal by opposing mTORC1. Cell 142, 468–479 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.041 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.041) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.May-Panloup P., Chretien M. F., Jacques C., Vasseur C., Malthiery Y., Reynier P. 2005. Low oocyte mitochondrial DNA content in ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. 20, 593–597 10.1093/humrep/deh667 (doi:10.1093/humrep/deh667) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fan W., et al. 2008. A mouse model of mitochondrial disease reveals germline selection against severe mtDNA mutations. Science 319, 958–962 10.1126/science.1147786 (doi:10.1126/science.1147786) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]