Abstract

Many flavoenzymes – oxidases and monooxygenases – react faster with oxygen than free flavins do. There are many ideas on how enzymes cause this. Recent work has focused on the importance of a positive charge near N5 of the reduced flavin. Fructosamine oxidase has a lysine near N5 of its flavin. We measured a rate constant of 1.6 × 105 M−1s−1 for its reaction with oxygen. The Lys276Met mutant reacted with a rate constant of 291 M−1s−1, suggesting an important role for this lysine in oxygen activation. The dihydroorotate dehydrogenases from E. coli and L. lactis also have a lysine near N5 of the flavin. They react with O2 with rate constants of 6.2 × 104 M−1s−1 and 3.0 × 103 M−1s−1, respectively. The Lys66Met and Lys43Met mutant enzymes react with rate constants that are nearly the same as the wild-type enzymes, demonstrating that simply placing a positive charge near N5 of the flavin does not guarantee increased oxygen reactivity. Our results show that the lysine near N5 does not exert an effect without an appropriate context; evolution did not find only one mechanism for activating the reaction of flavins with O2.

Keywords: Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, Fructosamine oxidase, Oxygen reactivity, Oxygen activation, Flavin

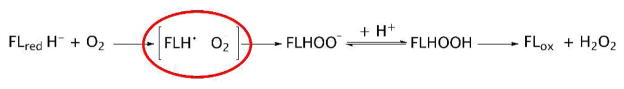

Flavins in solution, when reduced, react with molecular oxygen. However this reaction is not very fast. The reaction is slow because spin inversion is required for the reaction of a singlet (reduced flavin) with a triplet (O2) to form singlet products, oxidized flavin and H2O2 1, 2. This reaction occurs by electron transfer from reduced flavin to O2 yielding a caged radical pair – superoxide anion and semiquinone - which collapses to the C4a-hydroperoxide, which decomposes into H2O2 and oxidized flavin (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanism of reaction of reduced flavin with oxygen. It has been proposed that stabilizing the superoxide-semiquinone pair (circled in red) allows rapid reaction with O2.

Flavoproteins can be categorized based on their reactivity with O2 and the products that are formed from their reactions 3. Reduced oxidases react rapidly with O2 to give oxidized enzyme and H2O2 3. Reduced monooxygenases react rapidly to form the flavin hydroperoxide, which either oxygenates a substrate or eliminates H2O2 4. Although the radical pair in Figure 1 is thought to be an intermediate in oxidases and monooxygenases, it has not been observed, with the possible exception of one enzyme 5, suggesting that forming the radical pair is rate-determining. Dehydrogenases usually react slowly with O2, sometimes more slowly than free flavins, to give a mixture of H2O2 and superoxide anion 6. There is considerable interest in understanding how reduced flavoenzymes control oxygen reactivity 6. Structures of flavoproteins have been studied in an attempt to uncover clues for the basis of the acceleration of the reaction. At this time there is no clear understanding of how structures may explain oxygen reactivity.

There are many ideas on how enzymes can speed the reaction of reduced flavins with O2. These either focus on controlling the access of O2 to the flavin, or on stabilizing O2− in the caged radical intermediate. Access has been proposed to be controlled by channels through which O2 would approach the flavin, facilitating their encounter 7, 8. Recent molecular dynamics studies suggested that the protein matrix guides oxygen to a spot over C4a of the flavin for the reaction in some enzymes 9, 10. Crystal structures of L-galactono-γ-lactone dehydrogenase (GALDH), which belong to the vanillyl-alcohol oxidase family, reveal that an alanine is near the C4a position of the flavin; it reacts poorly with O2 11. Replacing the alanine residue of GALDH with a glycine increased oxygen activation by 400-fold, suggesting that the bulk of the alanine side-chain inhibits the flavoprotein dehydrogenase from reacting with molecular oxygen.

Ideas that consider increasing reactivity emphasize ways in which the protein could stabilize the obligate semiquinone–superoxide intermediate, especially by considering the polarity of the local environment in which O2− would form 12. Lewis acid catalysis could promote superoxide formation 13, 14. For example, glucose oxidase has two histidines near the flavin that appear to be important for oxygen activation. The positive charge of one of the histidines stabilizes the developing negative charge of O2−. The positive charge that activates oxygen is thought to be located on the product bound to the active site in choline oxidase 15.

Recent studies have shown that a lysine near N5 is important for reactivity of several enzymes with O2. Monomeric sarcosine oxidase, an enzyme which contains covalently bound flavin, catalyzes the oxidation of sarcosine 16, 17. Monomeric sarcosine oxidase has a lysine that hydrogen-bonds to a water which hydrogen-bonds to N5 of the flavin 18. Mutating Lys265 to the neutral methionine decreased the rate constant for the reaction of O2 by 8,000-fold 19. Crystallography showed that Cl− can bind in a pocket, near N5 of the flavin, lysine, and the water, suggesting that this is a pre-organized site for the reaction of O2 20. Another oxidase, N-methyltryptophan oxidase, also has a lysine near N5 of the flavin. Mutating this residue to glutamine decreased the rate constant for the oxygen reaction by ~2,500 fold 21. These are among the largest decreases in oxygen reactivity seen as an effect of site directed mutagenesis.

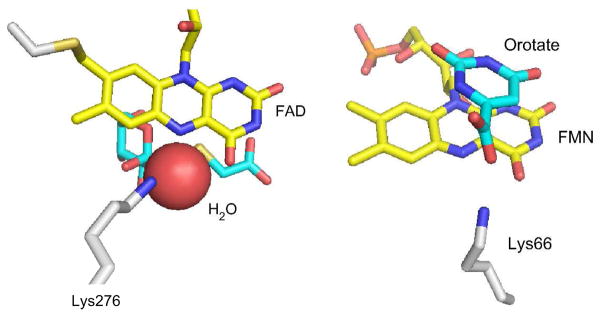

These observations show that a lysine near N5 is a key player in oxygen activation in these oxidases and thus sparked our interest in exploring the generality of lysine’s ability to accelerate the reaction of O2. The model-enzymes fructosamine oxidase and dihydroorotate dehydrogenases (DHODs) were studied because they all have lysines near N5 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fructosamine oxidase (left, from 3dje.pdb) and E. coli DHOD (right, from 1f76.pdb) active site structures. The DHOD complex with orotate is shown, but the structure remains the same in its absence. Note that each enzyme has a lysine near N5 of the flavin. The structure of a Class 1A DHOD is not shown, but is essentially identical.

Fructosamine oxidase from the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus is a flavoprotein oxidase that catalyzes the oxidation of the carbon-nitrogen bond of fructosamines. The amine substrate of the enzyme, formed physiologically by the spontaneous reaction of glucose and amino groups of amino acids, is oxidized to an imine and hydrolyzed non-enzymatically 22.

The reaction of the reduced wild-type fructosamine oxidase with O2 was studied in stopped-flow experiments. Flavin oxidation was observed by an increase in absorbance at 450 nm without any indication of an intermediate. Observed rate constants varied linearly with O2 concentrations, giving a bimolecular rate constant of 1.6 × 105 M−1s−1 23. Fructosamine oxidase has a lysine orthologous to that of monomeric sarcosine oxidase, the residue identified to be important in O2 reactivity. Lys276 was mutated to methionine. The reduced Lys276Met mutant reacts with O2 with a rate constant of 291 M−1s−1, a 550-fold decrease (Table 1). Again, there was no indication of an intermediate and the reaction produced H2O2 a. As with monomeric sarcosine oxidase, a large decrease in reactivity occurred, showing that lysine plays an important role in oxygen-activation in these two oxidases. The location of this positive charge is important. The Lys53Met mutant enzyme, where the lysine is nearly centered over the aromatic ring of the flavin on the si-face, reacted with O2 only 30-fold slower than wild-type 23.

Table 1.

Oxidative Half-reaction rate constants.

| Enzyme | kox (M−1s−1) | kox (wild-type)/kox (mutant) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type FAOXa | 1.6 × 105 b | |

| Lys276Met FAOXa | 291 | 550 |

| Lys53Met FAOXa | 5.6 × 103 b | 29 |

| Wild-type L. lactis DHOD | 3.0 × 103 | |

| Lys43Met L. lactis DHOD | 2.6 × 103 | 1.2 |

| Wild-type E. coli DHOD | 6.2 × 104 c | |

| Wild-type E. coli DHOD•Orotate | 5.0 × 103 c | 12.4 d |

| E. coli Lys66Met | 6.2 × 104 | 1.0 |

| E. coli His19Asn | 3.7 × 104 | 1.7 |

| E. coli Arg102Met | 5.9 × 104 | 1.1 |

Unrelated enzymes, DHODs, catalyze the oxidation of dihydroorotate to orotate during the only redox reaction in the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway. DHODs can be categorized into two different classes based on their sequences: Class 1 and Class 2 24. The Class 1 and 2 enzymes have different selectivity for oxidizing substrates and are also located in different compartments of the cell. The Class 2 enzymes are mitochondrial membrane proteins while Class 1 enzymes are cytosolic. Class 2 DHODs in vivo are oxidized by ubiquinone while Class 1A enzymes are oxidized by fumarate 3.

Class 2 E. coli DHOD has a lysine (Lys 66) near N5 of the isoalloxazine of the flavin 26. The rate constant for the reaction of O2 with the reduced wild-type enzyme is 6.2 × 104 M−1s−1 25, a value that is similar to that seen in some oxidases 27. The oxidative half-reaction of the Lys66Met mutant enzyme was studied by mixing the reduced enzyme with buffer containing various concentrations of O2. The Lys66Met mutant enzyme reacted with a rate constant of 6.2 × 104 M−1s−1, no change. Neither the wild-type nor the mutant enzyme formed an observable intermediate during their reactions and each produced H2O2 a.

The Class 1A DHOD from Lactococcus lactis also has a lysine (Lys43) near N5 of the isoalloxazine of the flavin 28. The rate constant for the reaction of O2 with the reduced wild-type enzyme is 3.0 × 103 M−1s−1. The Lys43Met mutant enzyme reacted with a rate constant of 2.6 × 103 M−1s−1, only 1.2-fold slower – virtually no change. Again, the removal of the lysine residue near N5 of the flavin had no significant impact. Neither the mutant nor the wild-type enzyme formed an intermediate during their reactions and each produced H2O2 a.

The reactivity of the mutant DHODs shows that lysine near N5 is not guaranteed to be important for oxygen reactivity. If O2 reacts elsewhere in DHOD, then the Lys66Met substitution should have little affect in the Class 2 enzyme, as observed. The physiological oxidizing substrate of Class 2 DHODs is ubiquinone, which binds near the methyls of the isoalloxazine of the flavin; the reaction occurs by two single-electron transfers 25. Therefore, Class 2 DHODs have evolved to transiently stabilize the flavin semiquinone. There are two conserved positively charged residues in the ubiquinone binding site, His19 and Arg102 in the E. coli enzyme. Conceivably, either of these positive charges could stabilize a developing negative charge if O2 reacted at this site. Therefore the reactivity of the His19Asn and Arg102Met mutant enzymes was determined. Neither change significantly altered the bimolecular rate constant for the reaction of O2 (Table 1), eliminating this site as the site where O2 reacts.

A unifying mechanism for oxygen activation by flavoproteins is being sought by many researchers. Our results show that a single mechanism cannot explain oxygen activation. The lysine near N5, a critical ingredient in oxygen activation for some oxidases, does not exert an effect without an appropriate context – some feature (or features) of the active site allows it to activate oxygen. Aligning the isoalloxazines of the structures of fructosamine oxidase and Class 1A and 2 DHODs shows that there is enough space near N5 and the lysine in each to accommodate O2. DHOD (not an oxidase) reacts with O2 at virtually the same rate regardless of the presence of a lysine near N5 – it plays no role in oxygen activation. Other structural features must be responsible. Mutagenesis eliminated the quinone binding bucket as the site of the reaction of O2. The hydrophilic pyrimidine binding site over the si-face of the flavin, ringed by hydrogen-bonding side-chains, does not appear to be the site of the reaction of O2 because the reduced enzyme-orotate complex reacts only about ten-fold slower than the free enzyme (Table 1) 25. The site of the reaction of O2 in DHODs remains a mystery. Our results suggest that many mechanisms are possible for oxygen activation by flavoproteins. This is consistent with the variety of structures of flavoproteins that react with oxygen 3. A small, reactive molecule like O2, which appeared after the origin of life and flavoenzymes, would be expected to find many sites to react.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant GM61087 to B.A.P. R.L.F was supported by NIGMS training grant GM07767. C.A.M. was supported by a University of Michigan Rackham Merit Fellowship and National Institutes of Health Grant GM61087-08-S1. F.C. was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation and the Belgian F.N.R.S. V.M.M. was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant EY07099.

We thank Maria Nelson for her work on creating and purifying the His19Asn and Arg102Met E.coli DHOD mutant enzymes.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DHOD

Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase

Footnotes

Cytochrome c, which is rapidly reduced by superoxide, was included in oxidation mixtures in order to determine the reduced oxygen species produced by the flavoenzyme. No superoxide was detected.

Materials and methods S1–S4. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bruice TC. Isr J Chem. 1984;24:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massey V. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22459–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagan RL, Palfey BA. Flavin-Dependent Enzymes. Vol. 7 Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palfey BA, McDonald CA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;493:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennati A, Gadda G. Biochemistry. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattevi A. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:276–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulombe R, Yue KQ, Ghisla S, Vrielink A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30435–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Lyubimov AY, Brammer L, Vrielink A, Sampson NS. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5368–77. doi: 10.1021/bi800228w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron R, Riley C, Chenprakhon P, Thotsaporn K, Winter RT, Alfieri A, Forneris F, van Berkel WJ, Chaiyen P, Fraaije MW, Mattevi A, McCammon JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10603–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903809106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saam J, Rosini E, Molla G, Schulten K, Pollegioni L, Ghisla S. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24439–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leferink NG, Fraaije MW, Joosten HJ, Schaap PJ, Mattevi A, van Berkel WJ. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4392–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang R, Thorpe C. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7895–901. doi: 10.1021/bi00246a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth JP, Klinman JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:62–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252644599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth JP, Wincek R, Nodet G, Edmondson DE, McIntire WS, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15120–31. doi: 10.1021/ja047050e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghanem M, Gadda G. Biochemistry. 2005;44:893–904. doi: 10.1021/bi048056j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner MA, Trickey P, Chen ZW, Mathews FS, Jorns MS. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8813–24. doi: 10.1021/bi000349z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner MA, Jorns MS. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8825–9. doi: 10.1021/bi000350y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trickey P, Wagner MA, Jorns MS, Mathews FS. Structure. 1999;7(3):331–45. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao G, Bruckner RC, Jorns MS. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9124–35. doi: 10.1021/bi8008642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kommoju PR, Chen ZW, Bruckner RC, Mathews FS, Jorns MS. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5521–34. doi: 10.1021/bi200388g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruckner RC, Winans J, Jorns MS. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4949–62. doi: 10.1021/bi200349m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerhardinger C, Taneda S, Marion MS, Monnier VM. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collard F, Fagan RL, Zhang J, Palfey BA, Monnier VM. Biochemistry. 2011 doi: 10.1021/bi1020666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Björnberg O, Rowland P, Larsen S, Jensen KF. Biochemistry. 1997;36:16197–205. doi: 10.1021/bi971628y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palfey BA, Björnberg O, Jensen KF. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4381–90. doi: 10.1021/bi0025666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nørager S, Jensen KF, Björnberg O, Larsen S. Structure. 2002;10:1211–23. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00831-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macheroux P, Massey V, Thiele DJ, Volokita M. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4612–9. doi: 10.1021/bi00232a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowland P, Nielsen FS, Jensen KF, Larsen S. Structure. 1997;5:239–52. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.