Abstract

Paramagnetic and superparamagnetic metals are used as contrast materials for magnetic resonance (MR) based techniques. Lanthanide metal gadolinium (Gd) has been the most widely explored, predominant paramagnetic contrast agent until the discovery and association of the metal with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), a rare but serious side effects in patients with renal or kidney problems. Manganese was one of the earliest reported examples of paramagnetic contrast material for MRI because of its efficient positive contrast enhancement. In this review, manganese based contrast agent approaches are discussed with a particular emphasis on their synthetic approaches. Both small molecules based typical blood pool contrast agents and more recently developed novel nanometer sized materials are reviewed focusing on a number of successful molecular imaging examples.

1. Introduction

The science of theranostics (or theragonostics) has emerged as an interdisciplinary area, which shows promise to understand the components, processes, dynamics and therapies of a disease at a molecular level.1–3 The potential of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging has long been realized for early detection, diagnosis and personalized treatment of diseases.4 The intrinsic MR contrast of different tissues is much more flexible than in other clinical imaging techniques; however, the detection of pathologies requires the utilization of contrast metals that differentiate the normal and diseased tissues by modifying their intrinsic parameters. As opposed to X-ray based techniques, these contrast metals are indirect agents and they do not appear visible by themselves. The technique involves paramagnetic and superparamagnetic metals to produce high resolution (<10 micrometres) noninvasive images in space and time of normal as well as abnormal cellular processes at a molecular or genetic level of function.5–7, 8–18 The efficiency of the contrast metals depends on their longitudinal (r1) and transverse (r2) relaxivity, which is defined as the increase of the nuclear relaxation rate (the reciprocal of the relaxation time) of water protons produced by one mmol/L of contrast agent. Paramagnetic metals shorten the longitudinal relaxation time (T1), and hence increase the relaxation rate (1/T1) of solvent water protons. Accumulating organs become bright in a T1-weighted (T1w) MRI sequence. Therefore these contrast agents are typically referred to as positive contrast media. Superparamagnetic iron oxides are regarded as negative contrast agents that influence the signal intensity mainly by shortening transverse relaxation time (T2) and T2* to produce the darkening of the contrast-enhanced tissue. These agents are generally composed of iron oxides (magnetite, Fe3O4, maghemite, γFe2O3, and others).

A contrast agent with relatively high relaxivity may be detected at lower concentrations, which in turn allows the imaging of subtle changes at the molecular level. The relaxivity is highly dependent on a dipolar mechanism of the ion-nuclear distance to the inverse 6th power. Therefore metal ions with a large spin number, S, are highly desired for MR contrast agents. Gadolinium (Gd) has been the most predominantly used paramagnetic lanthanide metal owing to the presence of seven unpaired electrons and slow electronic relaxation time in its trivalent state. The non-lanthanide metal manganese (Mn), which is critical in cell biology, represents one of the early reported examples of paramagnetic contrast material for MRI. In its bivalent state, the metal carries five unpaired electron to produce efficient positive contrast enhancement.19–21 Unlike the lanthanides and resembling Ca2+, it is a natural cellular constituent, and often acts as a cofactor for enzymes and receptors. The intrinsic properties of manganese include high spin number, long electronic relaxation time and labile water exchange. When used as a contrast agent, manganese ion (Mn2+) works similarly as other paramagnetic ions, like gadolinium (Gd3+) and copper (Cu2+), which are capable of shortening the T1 of water protons, thus increasing the signal intensity of T1w MR images. Additionally, Mn also has a minor T2 effect, which reduces the signal intensity to produce dark signals. At a biochemical level, manganese is involved in mitochondrial function, and the greater the mitochondria density in the cell, the higher the level of Mn uptake. Mitochondria are a rich component of hepatocytes and thus manganese is an excellent contrast agent for MR imaging of the liver and similar mitochondria rich organs like pancreas and kidneys.17 Taken together, these properties of manganese make it an attractive contrast agent for MRI.

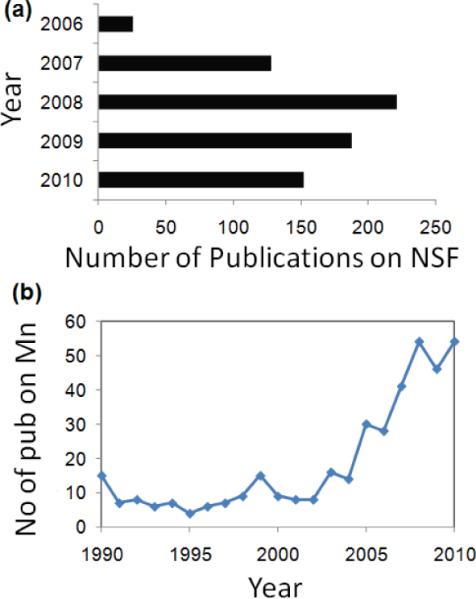

This report summarizes the progress achieved so far in the field of manganese based contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Specifically we review the different manganese contrast agent families, their synthetic strategies and associated properties. Although gadolinium has been the most popular choice among the paramagnetic metals, it has recently been linked with a medical condition known as nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF). NSF is a rare but potentially harmful side effect observed in some patients with severe renal disease or following liver transplant. It was first diagnosed in 1997, but only very recently in 2006 a possible link with Gd-containing contrast agents was identified. Since then the matter has been studied rigorously which is reflected in the surge in publications (Figure 1) relevant to NSF.11–15 For obvious reasons, this potential relationship has led to new concerns over the safety of Gd as an MRI contrast agent and to FDA restrictions on their clinical use.8–10,16–17 Furthermore, it has been recently reported that the high surface density presentation of gadolinium chelates on nanoparticle contrast agents could also induce significant, acute complement based activation in vitro and in vivo.18 With the increasing safety concerns associated with these conventionally pursued approaches, scientists are now in pursuit of a safer, more precise, and more effective way to practice personalized medicine. Toward this goal, much emphasis is now being put on alternative approaches based on non-lanthanide metals, in particular manganese, for T1w imaging. It is also important to mention here that although no relation between Mn and NSF has been found so far, the metal is still known to pose some toxicity when inhaled and in certain occupational settings.22–25 Although small amounts are essential to human health, overexposure to free Mn ions may result in the neurodegenerative disorder known as `manganism' with symptoms resembling Parkinson's disease. However, the fundamental issue for Mn, as well as other metals, as contrast agents is in their chelation stability. Chelation stability is an important property that reflects the potential release of free metal ions in vivo. Macrocyclic chelates are known to provide higher kinetic stability than their linear counter parts. Manganese is known to form thermodynamically and kinetically stable associates with macrocyclic ligands, e.g. diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) and dipyridoxal diphosphate (DPDP). Two Mn(II)-based agents, the liver-specific Mn-DPDP (Teslascan™)26 and an oral contrast containing Mn(II) chloride (LumenHance™),27 are available clinically for human use. A recent study in rats indicated that the optimal MnCl2 dose for manganese enhanced MRI of the rat would be 150–300 nmol. Relatively higher doses result in toxic reactions, causing retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death, impairing active clearance from the vitreous.22 A preclinical toxicological evaluation of 0.5 M solutions of Mangascan™ ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Mn-EDTA) and Pentamang diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (Mn-DTPA) at 5–10 ml/kg revealed toxic effects detected within 2 weeks in the general condition, bone marrow, cardiovascular and central nervous systems, and liver and kidney functions.28 The influence of the molecular architecture (linear vs dendritic) and chelator structure on the in vitro neurotoxicity in cultured rat primary neurons was also studied.29 A hydrosoluble dendritic manganese (II) has been compared with Mn-linear-DTPA and Mn-DPDP (Teslascan) within a concentration range of 0.1–10 mM. It has been observed that the linear-DTPA and dendritic-DTPA are relatively well tolerated. This points to the fact that a dendritic architecture is not much more toxic than a linear architecture of comparable molecular weights.

Figure 1.

Publication trend from Scopus: (a) surge in publications related to Gd and NSF; (b) renewed interest in manganese.

2. Contrast agent families

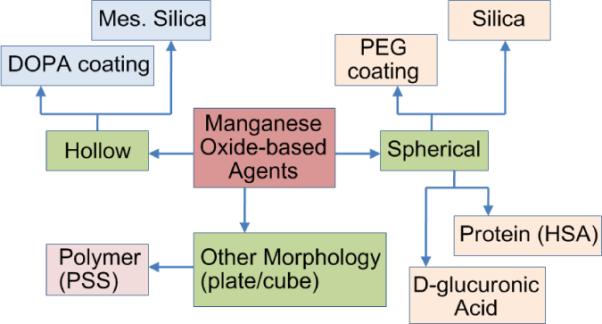

In this review, manganese-based contrast agents are classified into three broad categories, i.e., small molecule agents (Table 1), hybrid manganese agents (oxo clusters), and agents coupled (or incorporated into) to macromolecules or nanoparticulates.

Table 1.

Small molecule ligands used for manganese chelation

| Entry | Types of ligandsaa | Structure | Application reported | rl (mM−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alanine / VitaminD3 | Oral contrast | 8 (20 MHz) | |

| 2 | DPDP |

|

Rat carcinoma | 37.4 (20 MHz) (liposomal) |

| 3 | EDTA/EDTA-DPP |

|

Rat carcinoma | 37.4 (20 MHz) (liposomal) |

| 4 | EDTA-BOM | In suspension/in vitro | 55 (20 MHz) | |

| 5 | EDTA-diphenylcyclohexyl | In vivo (rabbit carotid artery injury) | Buffer: 5.8 (20 MHz) Rabbit plasma: 51 Human plasma: 46 | |

| 6 | DTPA-SA |

|

Dog liver | > relaxivity than Gd vesicles due to the slow release of Mn(II) |

| 7 | TTHA |

|

In vitro | 5.5 (10 MHz) |

| 8 | PcS4 |

|

Mice (human breast carcinoma) | 10.10 (10.7 MHz) |

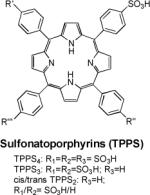

| 9 | TPPS4 |

|

Rat brain gliomas and other models | 10.36 (20 MHz) |

| 10 | TPPS3 | Subcut. mammary carcinoma (SMT-F) and MCF-7 human breast carcinoma | Mn-TPPS3 demonstrates the greatest relaxivity among other sulfonated porphyrins | |

| 11 | TPPS2 | |||

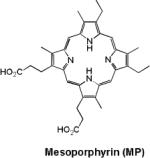

| 12 | Mesoporphyrin |

|

Hepatobiliary contrast agent | 1.9 (20 MHz) |

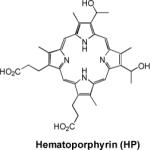

| 13 | Hematoporphyrin |

|

Rat liver | various |

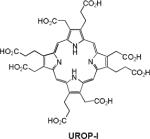

| 14 | UROP-1 |

|

Rat cerebral gliomas | 4.75 (10 MHz) |

| 15 | ATN-10 |

|

Brain tumor, cold injury model and cytotoxic brain edema | various |

| 16 | TPP |

|

Hepatocellular carcinomas | 13.0 (20 MHz) |

| 17 | HOP-8P |

|

Tumor-bearing (SCC-VII) mice | various |

DPDP, dipyridoxal diphosphate; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; DPP, dipeptidyl peptidases; BOM, benzyloxymethyl; DTP A, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid; TPPS, tetraphenylporphine sulfonate; UROP-1, URO porphyrin-1, TPP, tetraphenyl porphyrin.

2.1. Free ionic manganese

Free ionic manganese (MnCl2) is commonly used for Manganese-enhanced MRI (MEMRI)-based techniques.30 MEMRI is known for assessing tissue viability as well as providing a surrogate marker of cellular calcium influx and a tracer of neuronal connections. However, MEMRI is not the focus of this article and for further details readers are referred to some excellent review articles on this topic.31–33

MnCl2 represents one of the earliest examples of a manganese contrast agent with a measured r1 value of 8.0 ± 0.1 mM−1·s−1 at 20 MHz, 37°C and 6.0 mM−1·s−1 at 40 MHz, 40°C. A MnCl2-based oral contrast agent (Lumenhance®, Bracco Diagnostics) has been evaluated and approved for medical use.34 A major drawback to the use of manganese in ionic form as a contrast agent, however, is its cellular toxicity. The aqueous manganese (II) has been found to impart neurotoxicity with a LD50 in mice of 0.3 mmol·kg−1 injected intravenously and 1.0 mmol·kg−1 injected intraperitonially. Orally administered MnCl2 toxicity is improved relative to i.v. presumably due to the slow rates of metal absorption and presystemic elimination.35–37 Also, manganese in its ionic form has a very short plasma half-life and therefore cannot be considered as an effective blood pool agent. Therefore, critical to the successful application of manganese-based agents is their ability to reach the site of interest using a lower dose while maintaining detectability by MRI.

2.2. Chelated manganese (porphyrins, polycarboxylic acids etc.)

Chelated manganese deals with the apparent toxicity problem associated with free manganese ions and has been widely used as a blood pool contrast agent. The only clinically approved, injectable Mn(II) contrast agent is manganese(II) dipyridoxaldiphosphate (Mn-DPDP) for liver imaging. The safety factor (LD50/effective dose) of Mn-DPDP was 540, which was much higher in comparison to gadolinium diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA, safety factor = 60–100).38 The MR relaxivities of Mn-DPDP in aqueous solutions were found to be: r1=2.8 mM−1·s−1, r2 = 3.7 mM−1s−1 with the highest values in kidney. An EDTA chelated agent (similar to Gd-based MS-325) was reported by Troughton et al. for Mn(II) containing a diphenylcyclohexyl moiety.39 This group noncovalently binds to serum albumin and thereby increases the relaxivity by slowing down the rotation of the chelate.

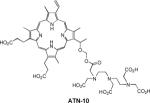

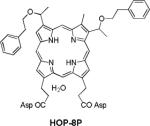

Manganese in its bivalent state has been chelated to porphyrins, such as sulfonatoporphyrins, where it undergoes rapid oxidation to Mn(III) (Table 1).40 One of the earliest example of sulfonatoporphyrins was manganese (III) tetra-(4-sulfonatophenyl) porphyrin (TPPS4) followed by analogs with progressively fewer sulfonate functionalities (TPPS3, TPPS2, Table 1).41–42 There are other examples of comparable manganese complexes which include uroporphyrin (UROP-1),43 mesoporphyrin, hematoporphyrin44–45 and metalloporphyrin (ATN-10).46Paramagnetic porphyrin-Mn has been reported to produce sustained tumor T1w enhancement up to at least 24 h following contrast injection in tumor-bearing (SCC-VII) mice.47 HOP-8 P (α-Aqua-13,17-bis(1-carboxypropionyl)carbamoylethyl-3,8 bis(1phenethyloxyethyl)-β-hydroxy-2,7,12,18-tetramethylporphyrinato manganese (III)) represents an example of a tumor specific manganese based agent which has been evaluated in a tumor-bearing mouse model.48

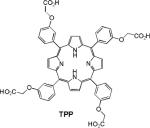

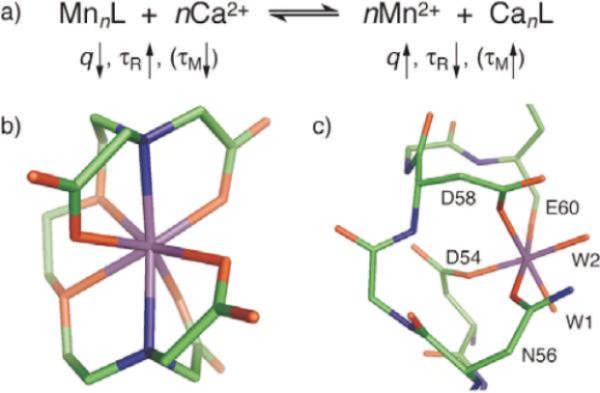

Ion sensing by MRI is emerging as an important area. Typically competitive displacement of paramagnetic ions is achieved, which results in alteration of solvent interaction parameters and changes in relaxivity and MRI contrast. Lippard and coworkers demonstrated a Ca-dependent displacement of manganese(II) ions bound to EGTA [ethylene glycol bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid] and BAPTA (1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid), which results in an increase in T1w MRI signal.49 The mechanism of MRI calcium sensors based on displacement of Mn2+ from chelated complexes is shown in Figure 2. Manganese complexes were assembled with EGTA, BAPTA, and calmodulin (CaM), all well-studied metal-binding molecules with selective affinity for Ca2+ ions. It has been observed that upon addition of excess Ca2+, Mn2+ ions are released from ligand molecules (L) including EGTA, BAPTA, and CaM. Dissociated Mn2+ ions have higher q, lower τR, and, for L = CaM, higher τM, than chelated manganese. This study indicates that the Mn2+ displacement mechanism for measuring Ca2+ or other ion concentrations by MRI influences longitudinal relaxivity and could be useful for applications in solution, as well as in other naturalistic environments where few extraneous metal ligands are present.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of MRI calcium sensors based on displacement of Mn2+ from chelated complexes. (τR and τM are rotational and water exchange time constants; q is the number of inner sphere).

2.3. Hybrid manganese agents

2.3.1. Manganese-based oxo clusters

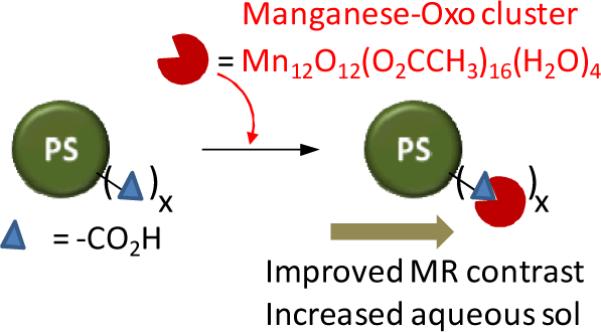

Manganese-based oxo clusters are considered as prototypical `Single Molecule Magnet' (SMM). At low temperature the high spin state (S = 10) and anisotropy of these oxo clusters results in favorable magnetic properties.50–53 Mertzman et al. recently showed that manganese-oxo clusters offer promise as an MRI contrast agent and their magnetic properties and water solubility are improved when they were conjugated onto the surface of polymer (e.g., polystyrene) beads (Figure 3).54 Mn-oxo cluster has a large number of unpaired electrons and has four coordinated waters that are exchanged rapidly on the NMR timescale due to the coordination to the labile Mn(III). It can undergo ligand exchange for attachment onto any surface containing carboxylic acid functionality. The reaction was straightforward and involved soaking the polystyrene beads in ethanolic solutions of Mn-oxo-cluster followed by centrifugation and washing of the brown powder to remove excess cluster. This is self-limiting and proceeds until a monolayer of clusters is attached. The relaxivity of the clusters were found to be highly dependent on the size of the polymer beads. An increase in the bead diameter from 47 nm to 209 nm resulted in a significant increase in R1 from 22.0 s−1 to 37.5 s−1.

Figure 3.

Surface attached manganese-oxo clusters improve MR contrast (PS: polystyrene beads).

Synthesis and MR characterization of two Mn(II)-monosubstituted polyoxometalates (MnPOMs), MnSiW11 and MnP2W17, were evaluated in vivo and in vitro as tissue-specific MRI contrast agent candidates.55 The measured relaxivities exhibited improved relaxation in comparison with Gd-DTPA. In vivo MR imaging in healthy rats demonstrated signal enhancement in organs e.g. liver and kidney, suggesting that these agents can produce sufficient signals for animal imaging.

2.3.2. Manganese-organic frame work

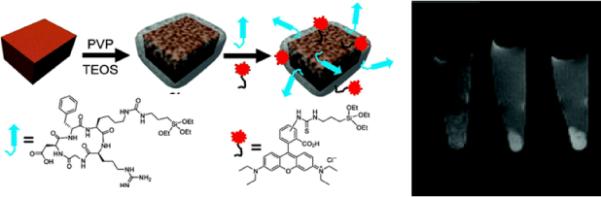

An example of another interesting class of hybrid materials is manganese-based core-shell nanoscale metal-organic frameworks (NMOFs). Wenbin Lin's group synthesized novel Mn-NMOFs comprised of terephthalic acid (BDC) and trimesic acid (BTC) bridging ligands by reverse-phase microemulsions.56 Mn-NMOFs are morphologically comparable to nanorods. Mn (BDC)(H2O)2 was synthesized by stirring a cetyl trimethylammonium bromid (CTAB)/1-hexanol/nheptane/water microemulsion containing equimolar MnCl2 and [NMeH3]2(BDC). Nanoparticles of Mn3(BTC)2(H2O)6 were prepared in a CTAB/1-hexanol/isooctane/water microemulsion mixture containing a Na3(BTC)/MnCl2 molar ratio of 2:3. (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

(a) Illustration of Mn-NMOF formation

The particle morphology was confirmed in anhydrous state by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) techniques, which revealed that the particles adopt uniform spiral rod structures with diameter 50–100 nm and lengths ~1–2 μm. The particles were made dispersible in water by a silica coating. Polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP)-coated particles under base-catalyzed condensation of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) produced a thin layer of silica shell, which provided a chemical basis for conjugating a fluorophore (rhodamine B) and a cell-targeting cyclic peptide (cRGDfk) for selective recognition of αvβ3 integrin, which is over-expressed in tumor angiogenesis. Rhodamine B- and c(RGDfK)-coupled particles demonstrated effective target-specific MR imaging to cancer cells in vitro, which was corroborated by optical imaging. The relaxivity offered by this system was modest and eventual release of large doses of Mn2+ ions inside cells further questions the practical applicability of this system due to the possible toxicity.

2.4. Macromolecular agents

A dendritic manganese (II) chelate has been evaluated by in vitro (relaxivity) and in vivo (toxicity and relaxivity) experiments as a MEMRI contrast agent.57 The influence of the molecular architecture (linear vs dendritic) and chelator structure on the in vitro neurotoxicity was also studied in cultured rat primary neurons. The Mn(II) DTPA-derived complexes were synthesized starting from a bromo derivative as depicted in Scheme 1. The bromide in the presence of methyl 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate and potassium carbonate in acetone led to the formation of methyl ester followed by the reduction of ester with LiAlH4 in THF. This allowed the preparation of the corresponding benzyl alcohol in 90% yield. Finally, the ligand was obtained by reaction of benzyl alcohol with commercially available diethylenetriaminepentaacetic dianhydride in the presence of triethylamine in dichloromethane. After purification, an equimolar solution of ligand and MnCl2 was reacted at pH 6.5 to produce manganese dendritic complex 1 in high yield. This hydrosoluble dendritic manganese (II) was compared with Mn-Linear-DTPA and Mn-DPDP (Teslascan™) within a concentration range of 0.1–10 mM. It has been observed that the linear-DTPA and dendri-DTPA are relatively well tolerated suggesting that dendritic architecture of comparable molecular weights are equally safe. The examples of other polymeric manganese contrast agents are based on novel hydrophilic dendritic Mn(II) complex derived from DTPA for MEMRI experiments for brain imaging. These complexes exhibit no in vitro neuronal toxicity at concentration ~1 mM. The MR properties were also found to be much better than that of the commercial MRI contrast agents (Gd-DTPA).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the dendritic manganese (II) chelate: i) Methyl-3,5-dihydroxybenzoate, K2CO3, (ii) LiAlH4, THF, 0°C; (iii) diethylenetriamine pentaacetic dianhydride, TEA; (iv) for Mn complex 1: MnCl2·4H2O, pH 7.

2.5. Nanoparticle based agents

Small molecule chelated contrast agents have been classically entrapped into liposomes, while the examples of other nanoparticulate agents were comprised of purely inorganic or included organic (and/or polymeric) components. Although liposomes have been widely used in the literature as a blood pool contrast agents, their apparent in vivo instability presents a problem. Also, liposomes injected into the blood stream quickly become captured and degraded by the immune system. Pegylated “stealth” liposomes last long but unexpected immune responses are reported to occur. Therefore, the conventional liposomes seldom make it to sites in the body other than the liver and the spleen, making them not an attractive choice for the molecular imaging applications. These problems were addressed very recently by several groups including ours. Examples of these agents typically include “soft” or “hard” type agents derived from colloidal emulsion, dendritic polymers or inorganic oxide based agents. In this section we will discuss the synthetic and MR properties of these agents in detail.

2.5.1. Liposome based agents

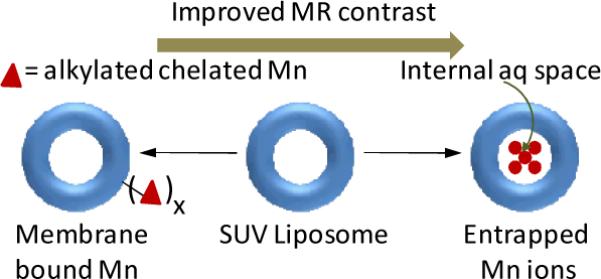

Manganese (II) ions have been incorporated into the phospholipid based liposomal bilayers to reduce the toxicity in mice in comparison to the free Mn(II). The construct had a r1 value of 35.34 mM−1 s−1 at 20 MHz. Various chelated manganese (polycarboxylic acid ligands e.g., EDTA,58 EDTA-DPP, DTPA, DTPA (PAS)59 and TTHA.60) were successfully used (Table 1). Chelates containing a BOM (benzyloxy methyl) moiety were also prepared to promote a noncovalent interaction with human serum albumin (HSA).61 The exchange rate of coordinated water was one order of magnitude higher compared to the exchange rates previously reported for Gd(III) complexes with octadentate ligands. These fast exchange rates can be attributed to the formation of macromolecular adducts with HSA to attain systems producing high relaxivity values compared to the analogous gadolinium based agents. Small unilamellar liposomes (SUVs) were prepared entrapping manganese chloride within the internal aqueous space of the vesicles or into the bilayer surface via membrane bound complexes as alkylated manganese.62

They were compared for in vitro relaxivity, stability, toxicity, and in vivo imaging in rats with liver tumors. Results indicate that the liposomes entrapping alkylated manganese had a concentration-dependent change in relaxivity that was maximal at a several-fold molar excess of phospholipids relative to the free manganese ion. On the other hand, liposomes bearing membrane-bound complexes showed relaxivity inversely proportional to lamellar size. In vivo imaging showed specific hepatic enhancement with manganese liposomes bearing alkylated complexes in comparison to the manganese ion entrapped liposomes.62 (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Examples of manganese incorporated liposomes.

2.5.2. “Soft” nanoparticle based agents

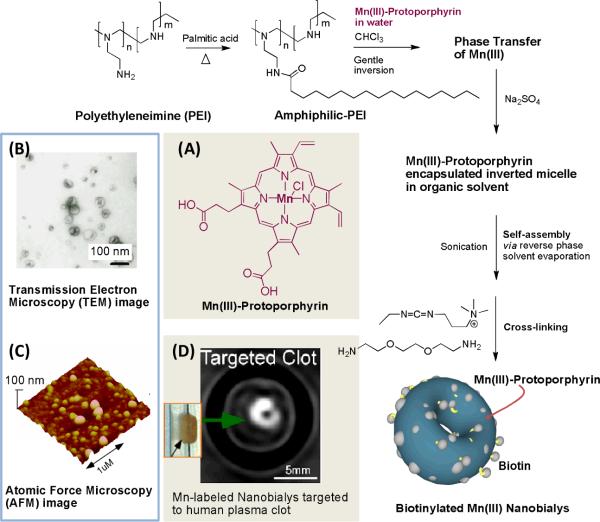

Very recently Pan et al. reported one of the first examples of MR imaging with trivalent manganese incorporated within a nanoparticle which morphologically resembles red blood cells.63 Toroidal shaped manganese (III)-labeled “nanobialys” represent an ideal `soft-type' biconcave polymer-lipid particle. Preliminary in vitro data show its potential as a targeted MR theranostic agent. Nanobialys were prepared through spontaneous self-assembly of amphiphilic hyperbranched polyethylenimine with a particle size within 180–200 nm and narrow polydispersities (Figure 6). Commercially available hyperbranched polyethyleneimine (MW=10kDa) were hydrophobically modified with either palmitic acid or linoleic acid through a nominal 55% conjugation of the 1° amines. The conjugation of the fatty acids was performed either by direct thermal coupling or using 1-(3′-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide methiodide (1.2 equiv) carbodiimide-mediated conjugation at ambient temperature. The amphiphilic polymer assumed inverted micellar structures in anhydrous chloroform that were able to transfer a novel water soluble contrast agent Mn(III)-protoporphyrin chloride (Mn-PPC, Figure 6A) in a kinetically stable, complex. Synergistic self-assembly of this agent alone or in presence of biotin-caproyl-DSPE (5 w/w% of total amphiphiles) produced the bialys presumably due to the formation of a bilayer structure. Hydrodynamic particle sizes for the biotinylated and non-biotinylated bialys were comparable (<200 nm), with a narrow distribution (polydispersities ~ 0.01). Biotin was used as a homing agent for targeting these particles to fibrin clots through classic avidin-biotin interactions and a well-characterized biotinylated fibrin-specific monoclonal antibody (NIB5F3). Manganese protoporphyrins were directly exposed to the surrounding water producing ionic r1 and r2 relaxivities of 3.7 ± 1.1 mmol−1 s−1 and 5.2 ± 1.1 mmol−1 s−1 per Mn ion and particulate relaxivities of 612,307 ± 7213 mmol−1 s−1 and 866,989 ± 10,704 mmol−1s−1 per particle, respectively.

Figure 6.

Preparation and characterization of manganese nanobialys. Reaction conditions: (1) anhydrous chloroform, gentle vortexing, room temperature; (2) aqueous solution of 2 [Mn(III)-protoporphyrin], inversion, room temperature, filter using short bed of sodium sulfate and cotton; (3) Biotin-Caproyl-PE, filter mixed organic solution using cotton bed, 0.2 μM water, vortex, gently evaporation of chloroform at 45°C, 420 mbar, 0.2 μM water, sonic bath, 50°C, 1/2 h, dialysis (2 kDa MWCO cellulose membrane) against water. (A) : Structure of Mn(III)-protoporphyrin; (Top left) (B) transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image (drop deposited over nickel grid, 1% uranyl acetate) and (C) atomic force microscope (AFM) image of nanobialys (drop deposited over glass); (D) magnetic resonance image (MR) of human plasma clot targeted with biotinylated nanobialys. (inset)

Moreover, the potential to entrap both hydrophobic and hydrophilic therapeutic agents (anticancer drugs) within these nanoparticles was demonstrated. The efficient (>98%) synthetic incorporation and in vitro dissolution confirmed the retention (80%) of chemotherapeutic compounds (e.g. doxorubicin and camptothecin). Nanobialys represented a unique platform for theranostic application which was demonstrated through targeted MR imaging in vitro using anti fibrin monoclonal Ab targeting to fibrin-rich clots. However, these particles presented modest in vivo contrast enhancement, which led to the exploration of alternative `soft-particle' approaches.

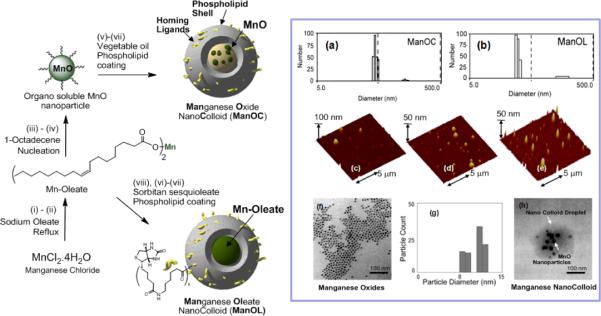

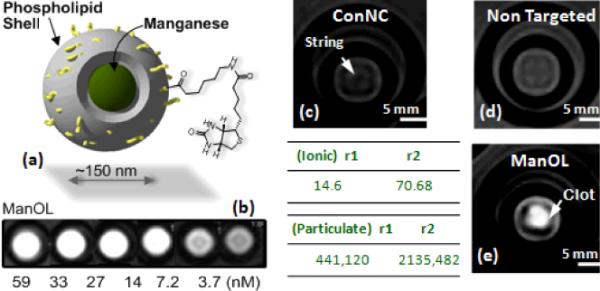

The alternative approaches included manganese oxide and manganese oleate nanocolloids (particle size >130 nm), which were developed by incorporating manganese (II) oxide (10 nm) particles or manganese (II) oleate within a hydrophobic core (vegetable oil) matrix encapsulated by phospholipids.64 (Figure 7) In a typical procedure, manganese chloride tetrahydrate was reacted with sodium oleate in a mixture of ethanol/water/hexane for 14 h at 80 °C and 4 h at ambient temperature to afford Mn (II)-oleate, an organically soluble manganese complex. Mn-oleate was then thermally decomposed in octadecene at 325 °C for 70 min to produce coated MnO nanoparticles (8–12 nm). These particles were highly uniform in size (Figure 7f) and easily dispersed in chloroform. Coated MnO was then incorporated in almond oil matrix (2 w/v%) and subjected to high pressure (20000 psi, 4 min) homogenization with the surfactant mixture to produce manganese oxide nanocolloids (ManOC). The surfactant mixture was mainly comprised of phosphatidylcholine (PC) (90 mol%) and biotin-caproyl-PE (1%) (Scheme 1) for targeting fibrin rich clots as discussed before. Manganese oleate nanocolloids (ManOL), containing only Mn-oleate suspended with sorbitan sesquioleate as the inner matrix, trapped even higher amounts of manganese (>2w/v%). This unique methodology incorporated nominally >100,000 manganese metal atoms on a per particle basis.

Figure 7.

Preparation and characterization of manganese nanocolloids. Reaction conditions: (Left) Preparation of ManOC and ManOL. (i)–(ii) sodium oleate, reflux, stirring; (iii)–(iv) 1-octadecene, 325°C/70 min, stirring; (v) suspended with vegetable oil (2 w/v%), vortex, mixing; evaporation of chloroform under reduced pressure, 45°C; (vi) thin film formation from phospholipids mixture; (vii) homogenization, 20,000 psi, 4 min, 0°C; (viii) Mn-oleate, suspended with sorbitan sesquioleate (>2 w/v%), vortex, mixing, evaporation of chloroform under reduced pressure, 45°C; then steps (vi), followed by (vii). (In box) Characterization of ManOC and ManOL. Number averaged hydrodynamic (DLS) distribution of (a) ManOC and (b) ManOL; (c)–(e) atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of ManOC, ManOL and ConNC respectively; (f) TEM image of coated MnO drop deposited over nickel grid and (g) their distribution; (h) TEM image of ManOC.

MR experiments at 3.0 T magnetic field strength demonstrated high-resolution T1w molecular imaging with ManOC and ManOL. (Figure 8) The specific relaxivities were found to be markedly and unexpectedly higher for the ManOL as compared to the ManOC. Results suggest that ManOL has outstanding potential for imaging intravascular microthrombus such as that associated with ruptured atherosclerotic plaque, and may provide adequate contrast to detect the very sparse bio-signatures such as αvβ3 integrin associated with angiogenesis in cancer and vascular diseases. Moreover, the overall safety and high efficiency (i.e. avidity) raises the potential of the platform for further transition of the work from research to clinical studies.

Figure 8.

MRI images of fibrin-targeted nanocolloids: (a) Structure of nanocolloid; (b) MR image of varying concentrations of ManOL phanotoms; (c) Control nanocolloid (no Mn; `ConNC'); (c) non targeted-ManOL and (d) fibrin targeted ManOL, bound to cylindrical plasma clots measured at 3 T (res: 0.73 mm × 0.73 mm × 5 mm).

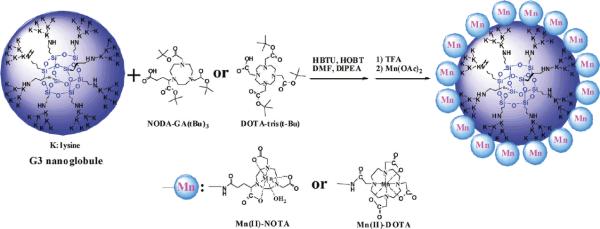

Tan et al. very recently reported the synthesis of a nanoglobular carriers, where macrocyclic Mn(II) chelates were conjugated to the lysine dendrimers with a silsesquioxane core.65 A generation 3 nanoglobular conjugate of Mn(II)-1,4,7-triaazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetate-GA amide (G3-NOTA-Mn) was also synthesized and evaluated. (Figure 9) Two different macrocyclic ligands NOTA (coordination no 6) and DOTA (corordination no 8) monoamide were used to chelate paramagnetic Mn(II) ions. The ligand effect on relaxivities of the agents was tested with macrocyclics having different coordination number. The synthetic scheme for the preparation of nanoglobular Mn(II)-DOTA and Mn(II)-NOTA conjugates is depicted in Figure 9. DOTA-tris(tBu) and excess of NODA-GA(tBu)3 were used for the conjugation of the ligands to the nanoglobules. The Boc functionality was deprotected with TFA to yield nanoglobule-DOTA-monoamide or nanoglobule-(NOTAGA) conjugates. Mn(II) complexes were prepared by reacting the nanoglobular ligand conjugates with large excess Mn(OAc)2 at 100 °C to achieve a complete complexation of Mn(II) with the ligands. Finally the excess manganese ions were removed by ultrafiltration and dialysis. Nominally >70% of the surface amino groups of the nanoglobules were conjugated with macrocyclic Mn(II) chelates. In this report, ionic relaxivity of G2–G4 nanoglobular Mn(II)-DOTA monoamide conjugates were determined. The relaxivities decreased with increasing generation of the carriers. Although the cellular toxicity of this agent is unknown, it exhibited good in vivo stability and were readily excreted via renal filtration in a rodent animal model. The construct also resulted in lower nonspecific liver enhancement than MnCl2 which points to their potential safety. They were also found to be effective for contrast-enhanced tumor imaging in nude mice bearing MDA-MB-231 breast tumor xenografts at a dose of 0.03 mmol Mn/kg. The advantages of this system include the controllable size, morphology and easy access to the functional groups on the surface, which makes the agent a promising example of “soft” nanometer sized manganese-based molecular contrast agent. Overall, they have great potential owing to their thermodynamic stability, high solubility in water and uniform size distribution. However, more synthetic advancements are needed to generate biocompatible and biodegradable systems for further translational work.

Figure 9.

Synthesis of G3 nanoglobular macrocyclic Mn(II) chelate conjugates with NODA or DOTA chelates.

2.5.3. “Hard” type inorganic nanoparticle based agents

The inorganic “hard” nanoparticle catagories include a major class of manganese based agents. A colloidal suspension of manganese sulfide (MnSC) represents one of the first examples of “hard” inorganic particles. The suspension was prepared by the co-precipitation of equal molar quantities of manganese acetate and sodium sulfide. The preparation was characterized as a salmon-colored suspension with an anhydrous state particle size of 0.1–10 μm observed by scanning electron microscopy. Chilton et al. investigated the effect of this suspension upon liver and lung spin-lattice relaxation times (T1) in rats following intravenous administration.66

Based on the seminal work by Hyeon and coworkers,67 there has been a recent surge in publications on biocompatible manganese oxide (MnO) nanoparticles for MR imaging. (Figure 10) These particles in either spherical or hollow morphology elicit bright signal enhancement and provide fine anatomic detail in the T1-weighted MR image in rodent models. Uniformly sized spherical MnO nanoparticles were prepared by thermal decomposition of manganese (II) oleate complexes at 300 °C.67 These particles are soluble in common organic solvents (e.g. chloroform, toluene etc.). The organically compatible nanoparticles (10–30 nm) were encapsulated in a either polyethyleneglycol (PEG) or phospholipids shell for increased water solubility and improved biocompatibility. They are anti ferromagnetic and therefore do not exert the susceptibility artifacts in MRI as observed with the super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO)-based T2* agents. These particles were shown to target breast cancer cells in a metastatic tumor in mouse brain and were used to label rat glioma cells by electroporation. The viability and proliferation of the labeled cells were similar to the non labeled cells and they produced “positive contrast” with an increased R1. However, the higher dose of MnO (785 μg Mn/ml) was found to be strongly toxic.68

Figure 10.

Examples of manganese oxide based MRI contrast agents.

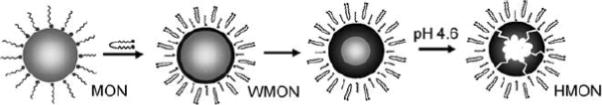

The relaxivity of MnO nanoparticles can be tuned by manipulation of their size and curvature. Manganese oxide nanoparticles (MONs, 20 nm) stabilized by oleic acid as well as water-dispersible manganese oxide nanoparticles (WMONs) were prepared and encapsulated with poly(ethylene glycol) phospholipids.69 The hollow manganese oxide nanoparticles (HMONs) were prepared by the selective removal of oxide phase from the WMONs. (Figure 11) HMON showed enhanced relaxivities and drug-loading capacities compared to those with solid interiors (WMON). Drug encapsulation capability combined with their efficient cellular uptake points to the potential of theranostic applications. HMONs with void interior spaces may offer advantages over perfectly spherical morphology, owing to their large water-accessible surface areas, which are capable of carrying high payloads of MR-active magnetic centers, and a large amount of therapeutics within the interior void.

Figure 11.

Formation of HMONs. (gray: MnO, black: Mn3O4)

A similar methodology was followed to prepare multifunctional HMONs by a bio-inspired surface functionalization approach, using 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (DOPA) as an adhesive moiety.70 Cationic polyethylenimine-DOPA conjugates were stably immobilized onto the surface of HMON due to the strong binding affinity of DOPA to metal oxides and functionalized with Herceptin antibody to selectively target breast cancer cells and deliver siRNA therapeutics.

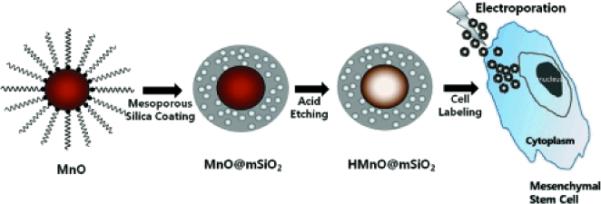

Very recently Hyeon group published a work on the synthesis of mesoporous silica-coated hollow manganese oxide (HMnO@mSiO(2)) nanoparticles as a novel T1w MRI contrast agent.71 The mesoporous structure of the nanoparticle shell helps to enable optimal access of water molecules to the magnetic core, and thereby an effective enhancement of R1 relaxation of water protons was achieved (0.99 mM−1s−1) at 11.7 T. (Figure 12) These nanoparticles exhibited high cellular uptake by adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), using electroporation, and were detected with MRI both in vitro and in vivo. These findings are encouraging and the hollow nanoparticles show great potential for MRI cell tracking using positive contrast. However, the average diameter of the particles was obtained as 65 nm (MnO core size ~15 nm). It is generally regarded that 6–10 nm is a typical kidney cut-off. Considering this and the fact that these “hard” type crystalline particles are never bio-metabolized, an improved synthetic strategy to reduce the particle is warranted for their clinical translation.

Figure 12.

Synthesis of HMnO@mSiO2 nanoparticles and labeling of Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) using electroporation.

In another example,72 oleate coated manganese oxide crystals were transferred to the aqueous phase by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) followed by a sol gel reaction for the formation of spherical mesoporous silica shells by hydrolysis and condensation of tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS). An iridium complex ([5-pyridyl-3-(butyl triethoxysilyl)pyrazolate]1[phenyl isoquinolinate]2 iridium) (Ir(III) complex) was strategically placed connecting the (EtO)3Si functional group, so that it is simultaneously encapsulated into the mesoporous silica framework during the co-condensation reaction. This unique design provides the capability for MR imaging, while the simultaneous red phosphorescence and singlet oxygen generation from the Ir complex opens up the possibility of optical imaging and inducing apoptosis, respectively.

Sub 10 nm manganese oxide (Mn3O4) particles were prepared as spheres, plates and cube morphologies.73 The manganese stearate (Mn(SA)2) salt was used as a precursor and a negatively charged polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) polymer was used to prepare Mn3O4@PSS nanoparticles. They exhibited paramagnetic behavior at room temperature on the basis of superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUID) measurements. It was found that nanoplate-treated A549 lung cancer cells showed a MR signal increase up to 139% in T1w images compared with untreated cells with a metal concentration as low as to 1.3 × 10−2 mM.

Baek et al. reported a one-pot synthesis of hydrophilic D-glucuronic acid-coated MnO nanoparticle ranging from 2–3 nm.74 High in vivo T1w MR contrast were obtained for various organs, showing the potential of these colloids as a sensitive positive contrast agent.

A facile, two-step surface modification strategy was reported by Huang et al. to achieve manganese oxide nanoparticles with prominent MRI T1 contrast.75 Oleate coated manganese oxide nanoparticles were synthesized using a pyrolysis method and dispersed in a 1:1 CHCl3/DMSO mixture solution, incubated and surface-exchanged with dopamine. This solution was added dropwise to an aqueous solution of human serum albumin (HSA). Because of the excellent ligand binding capacity of HSA and the post-modification amine-rich particle surface, the protein was efficiently adsorbed onto the particle surface. Analytical measurements with protein assay and ICP measurements determined that there were about 10 HSA molecules on each coated particle.

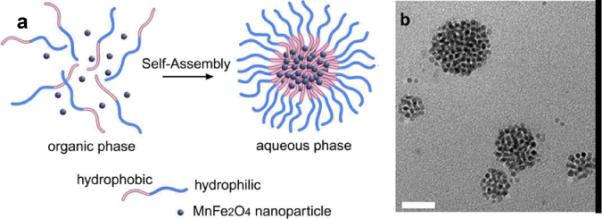

Lu et al. synthesized manganese ferrite nanoparticle (Mn-SPIO) micellar nanocomposites.76 These clustered nanocomposites were prepared from a self-assembly of diblock copolymer mPEG-b-PCL that noncovalently transferred Mn-SPIO nanoparticles into the micellar compartment (hydrodynamic diameter = 79 ± 29 nm). (Figure 13) Atomic force microscopy revealed the height of these composite particles as 8–50 nm. Mn-SPIO micelles had no relative detrimental effects on mouse macrophage cell lines as determined by their cytotoxicity measurements with MTT assay. At a magnetic field strength of 1.5T, these particles had a T2 relaxivity of 270 (Mn and Fe) mM−1 s−1, which was effective enough to bring significant liver contrast in vivo (signal intensity changes of −80% at 5 min after i.v.). The time window was about 36h for enhanced-MRI, which strongly improved the contrast between small lesions and normal tissues. Leung and co-workers prepared one-dimensional Mn-Fe oxide composite nanostructures of 400–1000 nm sizes in needles, rods, and wires form.77 The nanostructures were synthesized by the treatment of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles in the presence of cystamine by a linker-induced organization of manganese doped iron oxide nanoparticles. In vitro studies showed that the nanostructures could be transported into monocyte/macrophage cells (RAW264.7). The viability and proliferation potential of these cells were not affected at a labeling concentration <50 μg/mL. However their MR properties were not promising. The results from 1.5T MR indicated that the T2 relaxivities (r2) for nanoneedles, nanorods, and nanowires were 20.81 ± 0.58, 8.10± 0.31, and 6.62 ± 0.42 mM−1·s−1, respectively, which were lower than the corresponding iron oxide nanoparticle derivatives (e.g. VSOP-C184 and SHU-555C (Supravist)). It is believed that the formation of the larger 1-D nanostructures led to lower MR relaxivities.77

Figure 13.

(a) Illustartion of mPEG-b-PCL/Mn-SPIO micelle formation and Mn-SPIO nanocrystal clustering inside the micelle core. (b) TEM bright field image of Mn-SPIO micelles (copper grids); (scale bar = 50 nm).

2.5.4. Inorganic bulk particle approach

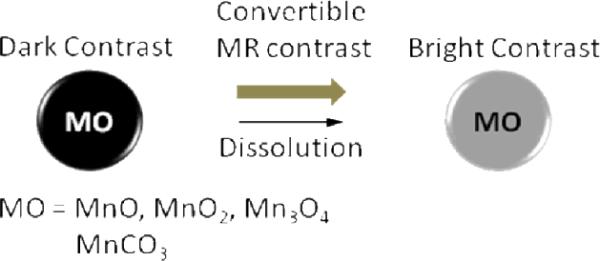

Recently, another class of manganese oxide particles was reported based on inorganic bulk material. Insoluble, inorganic manganese oxide particles (i.e., MnO, MnO2, and Mn3O4) and manganese carbonate (MnCO3) in form of bulk inorganic powder were developed as convertible contrast agents for molecular and cellular MRI agents.78 These Mn particles are typically water insoluble at neutral pH and exhibit high magnetic susceptibilities to produce dark contrast when using T2*-weighted MRI pulse sequences. (Figure 14) However, the particles were degraded by the abundant proteolytic enzymes in the predominantly acidic environment after cellular internalization and localization within endosomes and/or lysosomes. After internalization, they release Mn2+ ions, which are strong T1 MRI contrast agents. If the size of the particles can be controlled, the potential of the system is clearly noted for an entire class of novel environmentally responsive MRI contrast agents.

Figure 14.

Illustration of the manganese oxide-based “bulk” material as a convertible MR contrast.

3. Conclusion

Manganese offers great advantages as a T1 weighted MR contrast agent due to its favorable electronic configuration and enriched biochemical features. However, manganese in its free form is toxic and needs to be “masked” before administration. Manganese chelates, e.g. Mn-DPDP (Teslascan™), prevent the premature release of the metal and enhance the T1 signal. Teslascan™ has been successfully used in the clinic for the detection of liver lesions. It is the only FDA approved manganese contrast agent. The chelate DPDP dissociates in vivo into the metal and DPDP where the former is absorbed intra-cellularly and excreted in bile, while the latter is eliminated via the renal filtration. Recent discovery of NSF and its association with Gd based agents has triggered an important question over the future use of lanthanide based metals. Although manganese is not free from toxicity, it clearly offers an alternative MR contrast agent. With this aim in mind, manganese-based agents are gaining tremendous attention. Novel nanotechnologies are evolving with the goal to achieve high MR contrast by keeping the target specificity intact. Manganese in the form of nanoparticles reduces the risk of free metal based toxicities by preventing the premature loss of the free metal. Some strategies involved the use of liposomes, which are cleared rapidly from circulation due to uptake by the reticulo endothelial system (RES), primarily in the liver. Also with these systems, typically the production cost is very high and they are unsuitable for large scale preparation. The system further lacks stability due to the leakage and fusion of the entrapped metal from the uni- or multi-lamellar particles. There has been a steady growth of publications related to the use of “hard” type crystalline (and coated) manganese oxide based materials in various morphological states. Although these systems undoubtedly offer great contrast and targeting potential in vivo, their clearance mechanism has mostly remained under investigated. Keeping in mind an optimum kidney cut-off of <10nm, new synthetic strategies are desired to achieve particles in smaller size ranges. Dendritic systems are evolving rapidly as defined, macromolecular architectures. They offer the advantages of using a particle with “soft” nature, which are generally regarded as highly safe for the living system. The dendritic agents also retain the specificity for their intended target in vitro and in vivo. However, the synthetic pathways to a typical generation five (G5) dendrimer are long and require advanced skills, which may raise questions regarding their commercial success in industrial set up. Also, their ability to target sparse epitopes (e.g. angiogenic markers) is mostly uninvestigated. The “soft” nanocolloids incorporating manganese (II) oleate present huge potential in terms of their safety, ability to target sparse biological tissues and defined in vivo properties. More in depth studies are warranted to delineate their potential as manganese-based molecular imaging agents.

Acknowledgments

The financial support from the AHA 0835426N, 11IRG5690011, NIH under the Grants NS059302, CA119342, HL073646, CA1547371, NS073457 and the NCI under the Grant N01CO37007 is greatly appreciated.

Biographies

Dr. Dipanjan Pan is Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Division of Cardiology, Washington University in St. Louis with over 50 original publications, numerous abstracts, and patents in the area of materials science, chemistry and nanotechnology. He received his Ph.D. in Synthetic Chemistry from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, India in 2002 and pursued a postdoctoral career in polymer science and technology at the Department of Chemistry, Washington University in St. Louis. In 2005, he joined General Electric and worked as a part of the global research team towards the development of their biosciences initiatives. Dr. Pan joined the WU faculty in 2007. Subsequently, h e c o-invented several nanoparticle platforms for molecular imaging application with CT, MRI, optical and photoacoustic imaging. His research is broadly aimed at the understanding and developing novel lipid-based and polymeric nanoparticle platforms for molecular imaging, drug delivery and non viral gene delivery applications with a focus on structure, function and engineering processes. His multidisciplinary approaches encompass a variety of chemical, polymeric, molecular biological and analytical methods to address issues related to cardiovascular and cancer diseases. He is a research member of the Siteman Cancer Center and presently serves as the editorial board member of the Journal of Biotechnology and Biomaterials (OMICS) and World Journal of Radiology (Baishideng Publishing).

Anne Schmieder is a Senior Staff Scientist at Washington University in St Louis. She received her B.S. in Biochemistry from the University of Missouri-Columbia in 1999, and her M.S. degree in Biomedical Engineering from Washington University in St Louis in 2005. She subsequently joined the Washington University “Consortium for Translational Research in Advanced Imaging and Nanomedicine” (C-TRAIN) at the St Louis CORTEX Center. Her research focuses on the preclinical development and validation of multimodality molecular imaging agents and site targeted nanoparticle vehicles for diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other inflammatory conditions.

Samuel A. Wickline is Professor of Medicine, Physics, Biomedical Engineering, and Cell Biology and Physiology at Washington University. He received the B.A. degree from Pomona College, Claremont, CA in 1974 and the M.D. degree from the University of Hawaii School of Medicine, Honolulu, HI, in 1980. He completed postdoctoral training in Internal Medicine and Cardiology at Barnes Hospital, St. Louis, MO in 1987 and joined the faculty of the School of Medicine in the Cardiovascular Division before becoming Director of the Cardiovascular Division at Jewish Hospital and subsequently Co-Director of the Cardiovascular Division at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. He is Co-Director of the Cardiovascular Bioengineering graduate Program at Washington University and a member of the executive faculty of the Institute for Biological and Medical Engineering. He established the Washington University “Consortium for Translational Research in Advanced Imaging and Nanomedicine” (C-TRAIN) at the St Louis CORTEX Center devoted to diagnostic and therapeutic development of nanotechnology in concert with corporate and academic partners for broad based clinical applications. He also directs the “Siteman Center For Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence” at Washington University. Dr. Wickline is a founder of 2 local biotech startup companies in St Louis: Kereos, Inc., a nanotechnology startup company devoted to molecular imaging and targeted therapeutics; and PixelEXX Systems, Inc., a company that makes semiconductor nanoarrays for molecular diagnostics and microscopy. He also directs the new St Louis Institute of Nanomedicine, a consortium of academic and commercial partners devoted to enhancing regional infrastructure for the translational advancement of nanotechnology in medicine.

Dr. Lanza is Professor of Medicine and Bioengineering at Washington University in St. Louis with over 200 original publications, as well as abstracts, chapters, and patents across multiple disciplines. He received his Ph.D. from the University Of Georgia School Of Agriculture and joined Monsanto Company in1981, where he established and directed the preclinical research program supporting the development a 14-day parenteral, controlled release product, which is marketed today as Posilac ®. In 1988, Dr. Lanza matriculated at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago, where he received an MD degree in 1992 and developed expertise in ultrasonic imaging and patented the first acoustic molecular imaging agent. He completed residency in Internal Medicine and fellowship in Cardiology at Barnes-Jewish Hospital at Washington University School of Medicine, In 1994, as a fellow he co-invented a new perfluorocarbon based, ligand-targeted contrast agent, which has been broadly patented for use as a multimodality molecular imaging agent as well as for targeted drug delivery platform. Dr. Lanza joined the WU faculty in 1999. Subsequently, he has co invented numerous nanoparticle platforms for molecular imaging with MRI, ultrasound, CT, optical, and photoacoutics. In addition, he has developed nanoparticle platforms and compatible prodrugs to address a variety of unmet medical needs in cardiovascular disease, cancer, and arthritis. Dr. Lanza is the recipient of numerous awards for research excellence. He is an established principal investigator of the NIH and he is co-Director of the Consortium for Translational Research in Advanced Imaging and Nanomedicine (C-TRAIN), where his research continues to focus on developing new nanomedicine tools and converting these tools into translatable solutions for medical problems.

References

- 1.Pan D, Lanza GM, Wickline SA, Caruthers SD. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70(2):274–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanza GM, Caruthers SD, Winter PM, Hughes MS, Schmieder AH, Hu G, Wickline SA. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(Suppl 1):S114–26. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jang YY, Ye Z, Cheng L. Mol Imaging. 2011;10(2):111–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds F, Kelly KA. Mol Imaging. 2011;26 online. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan D, Carauthers SD, Chen J, Winter PM, SenPan A, Schmieder AH, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Future Med Chem. 2010;2(3):471–90. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2010;3:12, 62. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-12-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gore JC, Manning HC, Quarles CC, Waddell KW, Yankeelov TE. Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;25 doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.02.003. online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abu-Alfa AK. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18(3):188–98. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy C, Magee C, Eltayeb E, Gulmann C, Conlon PJ. Ir Med J. 2010;103(7):208–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen AY, Zirwas MJ, Heffernan MP. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(7):829–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin DR. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(3):427–30. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kay J, Czirják L. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):1895–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jalandhara N, Arora R, Batuman V. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Apr 6; doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.346. online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stratta P, Canavese C, Quaglia M, Fenoglio R. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(4):821–3. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguilera C, Agustí A. Med Clin (Barc) 2011 Mar 10; online. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KH, Fonda JR, Lawler EV, Gagnon D, Kaufman JS. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(3):458–67. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin DR, Krishnamoorthy SK, Kalb B, Salman KN, Sharma P, Carew JD, Martin PA, Chapman AB, Ray GL, Larsen CP, Pearson TC. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31(2):440–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pham CT, Mitchell LM, Huang JL, Lubniewski CM, Schall OF, Killgore JK, Pan D, Wickline SA, Lanza GM, Hourcade DE. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(1):123–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lauterbur PC, Dias MH, Rudin AM. In: Frontiers of Biological Energetics. Dutton PL, Leigh JS, Scarpa A, editors. Academic Press; New York: 1978. pp. 752–759. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendonca-Dias MH, Gaggelli E, Lauterbur PC. Sem Nucl Med. 1983;13:364–76. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(83)80048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wendland MF. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:581–594. doi: 10.1002/nbm.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thuen M, Berry M, Pedersen TB, Goa PE, Summerfield M, Haraldseth O, Sandvig A, Brekken C. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:855–865. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Churin AA, Karpova GV, Fomina TI, Vetoshkina TV, Dubskaia TIu, Voronova OL, Filimonov VD, Belianin ML. Eksp Klin Farmakol. 2008;71:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santamaria AB. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128:484–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertin A, Michou-Gallani A-I, Gallani JL, Felder-Flesch D. Toxicol in Vitro. 2010;24:1386–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skjold A, Amundsen BH, Wiseth R, Støylen A, Haraldseth O, Larsson HB, Jynge P. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(3):720–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Small WC, Macchi DD, Parker JR, Bernardino ME. Acad Radiol. 1998;5(Suppl 1):S147–50. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(98)80087-1. discussion S156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Churin AA, Karpova GV, Fomina TI, Vetoshkina TV, Dubskaia TIu, Voronova OL, Filimonov VD, Belianin ML, Usov VIu. Eksp Klin Farmakol. 2008;71(4):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertin A, Michou-Gallani A-I, Gallani JL, Felder-Flesch D. Toxicol in Vitro. 2010;24:1386–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massaad CA, Pautler RG. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;711:145–74. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-992-5_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pautler RG. Methods Mol Med. 2006;124:365–86. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-010-3:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wendland MF. NMR Biomed. 2004;17(8):581–94. doi: 10.1002/nbm.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva AC, Lee JH, Aoki I, Koretsky AP. NMR Biomed. 2004;17(8):532–43. doi: 10.1002/nbm.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernardino ME, Weinreb JC, Mitchell DG, et al. Safety and optimum concentration of a manganese chloride-based oral MR contrast agent. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 1994;4(6):872–876. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880040620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenberg DM, Copp DH, Cuthbertson EM. J Bio Chem. 1943;147:749–756. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima S, Hirai M, Kiyozumi M, Sasawa Y, Nakagawa M, Shin-o T. Chem Pharm Bull. 1983;31:2459–2465. doi: 10.1248/cpb.31.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandstr̈om B, Davidsson L, Cederblad Å , Eriksson R, Lonnerdal B. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol. 1986;59:60–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1986.tb02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elizondo G, Fretz CJ, Stark DD, Rocklage SM, Quay SC, Worah D, Tsang YM, Chen MC, Ferrucci JT. Radiology. 1991;178(1):73–78. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.1.1898538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Troughton JS, Greenfield MT, Greenwood JM, Dumas S, Wiethoff AJ, Wang J, Spiller M, McMury TJ, Caravan P. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:6313–6323. doi: 10.1021/ic049559g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchler JW. The Porphyrins. vol I A. Academic Press; New York: 1979. pp. 389–483. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Place DA, Faustino PJ, Berghmans KK, van Zijl PCM, Chesnick AS, Cohen JS. Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;10:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(92)90446-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiel RJ, Musser DA, Mark EH, Mazurchuk R, Alletto J. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90097-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmiedl UP, Nelson JA, Robinson DH, Michalson A, Starr F, Frenzel T, Ebert W, Schuhmann-Giampieri G. Invest Radiol. 1993;28:925–932. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199310000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fawwaz RA, Winchell HS, Frye F, Hemphill W, Lawrence JH. J NuclMed. 1969;10:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fawwaz RA, Hemphill W, Winchell HS. J Nucl Med. 1971;12:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujimori H, Matsumura A, Yamamoto T, Shibata Y, Yoshizawa T, Nakagawa K, Yoshii Y, Nose T, Sakata I, Nakajima S. Acta Neurochir. 1997;70:167–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6837-0_51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takehara Y, Sakahara H, Masunaga H, Isogai S. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1681–1685. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takehara Y, Sakahara H, Masunaga H, Isogai S, Kodaira N, Sugiyama M, Takeda H, Saga T, Nakajima S, Sakata I. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:549–553. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Atanasijevic T, Zhang X, Lippard SJ, Jasanoff A. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:2589–2591. doi: 10.1021/ic100150e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lis T. Acta Crystallogr. Sect B: Struct Crystallogr Cryst Chem. 1980;36:2042. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caneschi A, Gatteschi D, Sessoli R, Barra A-L, Brunel L-C, Guillot M. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5873. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sessoli R, Gatteschi D, Caneschi A, Novak M. Nature. 1993;365:141. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christou G, Gatteschi D, Hendrickson D, Sessoli R. MRS Bull. 2000;25:66. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mertzman JE, Kar S, Lofland S, Fleming T, Keuren EV, Tong YY, Stoll SL. Chem Commun. 2009;45:788–790. doi: 10.1039/b815424d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Z, Li W, Li X, Pei F, Wang X, Lei H. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor KM, Rieter WJ, Lin W. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14358–14359. doi: 10.1021/ja803777x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertin A, Steibel J, Michou-Gallani AI, Gallani JL, Felder-Flesch D. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20(4):760–7. doi: 10.1021/bc8004683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strijkers GJ, Mulder WJ, van Tilborg GA, Nicolay K. Med Chem. 2007;7:291–305. doi: 10.2174/187152007780618135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwendener RA, Wüthrich R, Duewell S, Wehrli E, von Schulthess GK. Invest Radiol. 1990;25:922–932. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rongved P, Klaveness J. Carbohydr Res. 1991;214:315–323. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(91)80038-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aime S, Anelli PL, Botta M, Brocchetta M, Canton S, Fedeli F, Gianolio E, Terreno E. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7:58–67. doi: 10.1007/s007750100265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Unger E, Fritz T, Shen DK, Wu G. Investigative Radiology. 1993;28(10):933–938. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199310000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan D, Caruthers SD, Hu G, Senpan A, Scott MJ, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(29):9186–7. doi: 10.1021/ja801482d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pan D, Senpan A, Caruthers SD, Williams TA, Scott MJ, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Chem Commun (Camb) 2009;22:3234–6. doi: 10.1039/b902875g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan M, Ye Z, Jeong EK, Wu X, Parker DL, Lu ZR. Bioconjug Chem. 2011 Apr 19; doi: 10.1021/bc100573t. online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chilton HM, Jackels SC, Hinson WH, Ekstrand KE. J Nucl Med. 1984;25(5):604–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Na HB, Lee JH, An K, Park YI, Park M, Lee IS, Nam DH, Kim ST, Kim SH, Kim SW, Lim KH, Kim KS, Kim SO, Hyeon T. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(28):5397–401. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gilad AA, Walczak P, McMahon MT, Na HB, Lee JH, An K, Hyeon T, van Zijl PC, Bulte JW. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shin J, Anisur RM, Ko MK, Im GH, Lee JH, Lee IS. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(2):321–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bae KH, Lee K, Kim C, Park TG. Biomaterials. 2011;32(1):176–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim T, Momin E, Choi J, Yuan K, Zaidi H, Kim J, Park M, Lee N, McMahon MT, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Bulte JW, Hyeon T, Gilad AA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(9):2955–61. doi: 10.1021/ja1084095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peng YK, Lai CW, Liu CL, Chen HC, Hsiao YH, Liu WL, Tang KC, Chi Y, Hsiao JK, Lim KE, Liao HE, Shyue JJ, Chou PT. ACS Nano. 2011 May 6; doi: 10.1021/nn200928r. Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang CC, Khu NH, Yeh CS. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):4073–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baek MJ, Park JY, Xu W, Kattel K, Kim HG, Lee EJ, Patel AK, Lee JJ, Chang Y, Kim TJ, Bae JE, Chae KS, Lee GH. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2010;2(10):2949–55. doi: 10.1021/am100641z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang J, Xie J, Chen K, Bu L, Lee S, Cheng Z, Li X, Chen X. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46(36):6684–6. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01041c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu J, Ma S, Sun J, Xia C, Liu C, Wang Z, Zhao X, Gao F, Gong Q, Song B, Shuai X, Ai H, Gu Z. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2919–2928. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leung KC, Wang YX, Wang H, Xuan S, Chak CP, Cheng CH. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci. 2009;2:192–198. doi: 10.1109/TNB.2009.2021521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shapiro EM, Koretsky AP. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:265–269. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]