Abstract

Human NUDT5 (hNUDT5) hydrolyzes various modified nucleoside diphosphates including 8-oxo-dGDP, 8-oxo-dADP and ADP-ribose (ADPR). However, the structural basis of the broad substrate specificity remains unknown. Here, we report the crystal structures of hNUDT5 complexed with 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP. These structures reveal an unusually different substrate-binding mode. In particular, the positions of two phosphates (α and β phosphates) of substrate in the 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP complexes are completely inverted compared with those in the previously reported hNUDT5–ADPR complex structure. This result suggests that the nucleophilic substitution sites of the substrates involved in hydrolysis reactions differ despite the similarities in the chemical structures of the substrates and products. To clarify this hypothesis, we employed the isotope-labeling method and revealed that 8-oxo-dGDP is attacked by nucleophilic water at Pβ, whereas ADPR is attacked at Pα. This observation reveals that the broad substrate specificity of hNUDT5 is achieved by a diversity of not only substrate recognition, but also hydrolysis mechanisms and leads to a novel aspect that enzymes do not always catalyze the reaction of substrates with similar chemical structures by using the chemically equivalent reaction site.

INTRODUCTION

Nucleic acid bases in cells are easily modified by reactive oxygen species. Of these modified bases, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG), an oxidized form of guanine, is one of the major sources of spontaneous mutagenesis because it can pair with adenine and cytosine with almost equal efficiencies (1–3).

Escherichia coli MutT has a high specificity for its substrates, 8-oxoG-containing nucleotides (8-oxo-dGTP, 8-oxo-dGDP, 8-oxo-GTP and 8-oxo-GDP), and catalyzes their hydrolysis to the corresponding nucleoside monophosphates. These 8-oxoG-containing nucleotides are available for DNA or RNA synthesis because 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-GDP are readily phosphorylated to generate 8-oxo-dGTP and 8-oxo-GTP, respectively (4–7). In this way, MutT strongly avoids replicational and transcriptional errors caused by 8-oxoG (4,8,9). Recently, we determined the crystal structures of several forms of MutT and revealed how MutT strictly discriminates the 8-oxoG-containing nucleotides from canonical guanine nucleotides (10,11).

Mammalian cells also have enzymes capable of eliminating 8-oxoG-containing nucleotides from the nucleotide pool. These include MTH1, MTH2 and NUDT5, which have broad substrate specificity for various oxidized nucleotides. Human MTH1 (hMTH1) catalyzes the hydrolysis of 8-oxo-dGTP, 2-oxo-dATP, 2-oxo-ATP, 8-oxo-dATP and 8-oxo-GTP(12–14). Human NUDT5 (hNUDT5) hydrolyzes 8-oxo-dGDP, 8-oxo-GDP, 8-oxo-dADP, 2-oxo-dADP and 5-CHO-dUDP into their corresponding nucleoside monophosphates and inorganic phosphates (Pi) (15–17). Since 8-oxo-dGDP inhibits hMTH1 activity (12,18), the catalytic activity of hNUDT5 also results in the promotion of hMTH1 activity as well as in a reduction in the amount of 8-oxo-dGTP generated from 8-oxo-dGDP by nucleoside diphosphate kinase. Thus, hNUDT5 has a role in preventing replicational and transcriptional errors in human cells. The biological significance of hNUDT5 has also been demonstrated by experiments using mutT-deficient E. coli mutant cells (15,16). According to these studies, the frequency of spontaneous mutation and the production of erroneous proteins by oxidative damage in mutT− cells can be recovered to wild-type levels by expression of hNUDT5. In addition, the recent report has shown that the knockdown of hNUDT5 in human 293T cells increased the A:T to C:G transversion mutations induced by 8-oxo-dGTP, as did the knockdown of hMTH1 (19). This means that because 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dGTP are interconvertible by cellular enzymes, the decreased 8-oxo-dGDPase activity in the NUDT5-knocked-down cells could increase the 8-oxo-dGTP concentration.

Meanwhile, hNUDT5 was originally identified as an ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase (ADPRase) that catalyzes the hydrolysis of ADPR to AMP and ribose 5′-phosphate (R5P). ADPR is generated by turnover of NAD+, cyclic ADPR, mono-ADP-ribosylated proteins and poly-ADP-ribosylated proteins. ADP-ribosylation of proteins plays important roles in cellular process such as cell signaling, DNA repair, transcription and cell death (20). However, high concentration of ADPR in cells would result in non-enzymatic ADP-ribosylation of proteins and give deleterious effects for organisms. Therefore, hNUDT5 seems to prevent non-enzymatic ADP-ribosylation of proteins (21–23). The crystal structures of hNUDT5 in the apo form and in ternary complexes with the substrate ADPR and an undetermined metal ion (ADPR complex), the product AMP and Mg2+, and the nonhydrolyzable ADPR analog α,β-methylene-ADPR (AMPCPR) and Mg2+ (AMPCPR complex) have been determined, and the recognition and hydrolysis reaction mechanisms of ADPR by hNUDT5 have been studied by means of mutagenic and structural analyses (24,25). However, as described above, hNUDT5 is not just an ADPRase, it is also a multi-functional hydrolase that contributes greatly to the removal of various deleterious compounds from cells by hydrolysis. Although the chemical structures of these substrates—except for the moiety ‘X’ linked to the nucleoside diphosphate—are similar (Figure 1), hNUDT5 is the only reported enzyme that hydrolyzes a substrate in which the X moiety is absent (X-lacking substrate) among the members of the ADPRase family so far. Nevertheless, how hNUDT5 obtains such extremely broad substrate specificity and catalyzes these substrates remains unknown.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of hNUDT5 substrates. Atom numbering is shown on 8-oxo-dGDP. Characteristic features of the oxidized bases are shown in red. The hydrolysis cleavage sites are shown by dashed lines.

NUDT5, as well as MutT, MTH1 and MTH2, belong to the Nudix (nucleoside diphosphate linked to another moiety X) hydrolase superfamily of versatile enzymes that are defined by the having of a consensus MutT signature (Nudix motif), i.e. GX5EX7REUXEEXGU, where U is a hydrophobic amino acid and X is any amino acid. Nudix hydrolases catalyze the hydrolysis of a variety of substrates, including oxidatively damaged nucleotides, ADP-sugars, diadenosine polyphosphates (ApnA), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), in the presence of divalent cations (26). Current genome analyses have found a large number of open reading frames containing the MutT signature, but the functions, i.e. the substrates, of a vast majority of the proteins encoded by the open-reading frames have not been identified because of a lack of homology outside the MutT signature. Although many crystal structures of Nudix proteins with unknown function have been determined and deposited to Protein Data Bank, only few structures have been published (27,28) and it is difficult to predict their substrates on the basis of their active site structures. Further, understanding the recognition and reaction mechanisms for 8-oxo-dGDP and other substrates by hNUDT5 is difficult even if we consider the crystal structure of hNUDT5 in complex with ADPR and the crystal structure of MutT in complex with 8-oxo-dGMP (11,24). Therefore, in order to explain the extremely broad substrate specificity of hNUDT5, it is necessary to determine the crystal structures of hNUDT5 in complexes with oxidized nucleoside diphosphates.

In this study, we present the crystal structures of hNUDT5 complexed with 8-oxo-dGMP (hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGMP), Mn2+ and 8-oxo-dGDP (hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+) and Mn2+ and 8-oxo-dADP (hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+). A comparison of these structures with the structure of the ADPR complex illustrates extremely different substrate-binding modes for oxidized nucleotides from ADPR, suggesting differences of nucleophilic substitution sites among these substrates. To verify whether the suggestion is accepted, we determined the substitution sites of 8-oxo-dGDP and ADPR using 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of the reaction mixtures in 18O-labeled water. As a result, we found that hNUDT5 catalyzes nucleophilic substitutions by water at different phosphorus atoms of the substrates with similar chemical structures, thereby producing similar products.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification

For crystallization, hNUDT5 (residues 1–210) was prepared from full-length hNUDT5 and subcloned into pET28b(+) vector (Novagene) with an N-terminal His-tag. The plasmid was transformed into the E. coli strain BL21(DE3). The transformed cells were grown in LB media at 37°C in the presence of 50 μg/ml kanamycin until A600 reached 0.6. Cells were then induced with 0.01 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h at 37°C. The protein was purified by using Ni-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow resin (GE Healthcare), followed by purification using a HisTrap HP Column (GE Healthcare) and thrombin protease digestion. Purification of hNUDT5 was subsequently performed through Superdex 75 gel filtration chromatography (GE Healthcare). The protein was concentrated in 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM 2-mercaptho-ethanol to a final concentration of ∼20 mg/ml. The construct was previously shown to have comparable enzymatic activity to that of the full-length enzyme (25).

Crystallization and data collection

Synthesis of 8-oxo-dGMP, 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP was performed as described previously (12,17). The protein solution (10 mg/ml) was incubated with 2 mM nucleotide and 5 mM MnCl2 at room temperature for a few minutes before crystallization. All crystals were obtained by the hanging- or sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 20°C.

Crystals of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGMP and hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ were grown from a drop consisting of equal volumes of the protein solution and the reservoir solution containing 0.8 M NaH2PO4/1.2 M K2HPO4 and 0.1 M acetate (pH 4.5), and 0.2 M ammonium acetate, 35% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350 and 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 6.2), respectively. The crystals of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+ were also obtained under similar conditions, as were the crystals of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+, with a slight modification. Namely, the reservoir solution contained 30% (w/v) rather than 35% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350. Both substrate complex crystals were obtained in 3 days and were immediately flash-cooled to avoid reaction within the crystals.

Diffraction data were collected at beamlines BL41XU and BL44XU at SPring-8 (Harima, Japan) and at beamlines NW-12A, BL5A and BL17A at the Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan). The diffraction dataset used for refinement of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGMP was collected to a resolution of 2.3 Å under cryocooled conditions at −173°C with 25% (w/v) sucrose in mother liquid as a cryoprotectant at a wavelength of 0.9 Å at beamline BL44XU. Diffraction data used for refinements of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ and hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+ were collected to 2.1 and 2.05 Å resolution at a wavelength of 1.0 Å at beamlines BL41XU and NW12, respectively. Both data sets were also collected at the wavelength of 1.5 Å for determination of positions for Mn2+ ions. All diffraction data were processed using the HKL2000 Suite (29). Data collection statistics and refinement parameters are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ | hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGMP | hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Beam line | SPring-8 BL41XU | SPring-8 BL44XU | PF-AR NW12 |

| Space group | C2 | C2 | C2 |

| Unit cell parameters | |||

| a/b/c (Å) | 113.2/40.4/99.4 | 112.7/40.0/98.5 | 113.6/40.7/99.8 |

| β (°) | 121.6 | 121.5 | 121.6 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 | 0.900 | 1.000 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0–2.1 (2.18–2.10) | 50.0–2.3 (2.38–2.30) | 50.0–2.05 (2.09–2.05) |

| Number of observed reflections | 155 670 | 38 488 | 172 327 |

| Number of unique reflections | 22 415 | 15 339 | 24 799 |

| Completeness (%) | 97.6 (87.7) | 90.8 (64.9) | 99.4 (97.3) |

| Rmerge (%)a | 6.9 (36.8) | 8.0 (42.6) | 5.2 (36.6) |

| <I/σI> | 31.3 (3.4) | 15.9 (1.8) | 37.7 (5.3) |

| Refinement | |||

| PDB ID Code | 3AC9 | 3L85 | 3ACA |

| Rcryst/Rfree (%)b | 19.5/23.6 | 21.5/26.1 | 19.9/24.7 |

| Number of atoms | |||

| Protein | 3034 | 3034 | 3038 |

| Water | 167 | 75 | 250 |

| Nucleotide | 47 | 37 | 54 |

| Mn2+ ion | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

| Most favored | 91.1 | 88.7 | 90.5 |

| Additional allowed | 8.9 | 11.3 | 9.5 |

| Generously allowed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disallowed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RMSD in bonds (Å) | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| RMSD in angles (°) | 0.915 | 0.621 | 0.584 |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell.

a

is the mean value of

is the mean value of

b Rfree was calculated from the test set (5% of the total data).

Rfree was calculated from the test set (5% of the total data).

Structure determination and refinement

The structure of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGMP was determined by using the phase data from the ADPR-binding structure (PDB code: 2DSC). Refinement was carried out with CNS and PHENIX (30,31).

The structures of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ and hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+ were determined using the phase data from the hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGMP structure. Refinements of each structure were carried out with CNS and subsequently with REFMAC5 (30,32), including refinement of atomic displacement parameters by the translation, liberation and screw (TLS) method, with each monomer in the asymmetric unit treated as a single TLS group. The metal sites were located in anomalous difference Fourier maps at λ = 1.5Å. Final occupancy refinement of the Mn2+ ions and structure refinement were carried out with PHENIX (31).

All structures contained two hNUDT5 molecules in an asymmetric unit, forming a homodimer related by a non-crystallographic 2-fold axis. No electron density corresponding to N-terminal 1–12 or 1–13 residues in all structures was observed, and these residues were omitted from the models.

Manual model building was performed periodically using Coot (33). The stereochemical quality of all structures was evaluated using PROCHECK (34). Superposition of the structures was carried out using Lsqkab (35).

31P NMR analysis

The ADPR hydrolysis reaction was carried out under the following conditions: 1.7 mM ADPR, 57 mM Tris–HCl (pH 9.0), 9.2 mM MgCl2, 5.7 µg/ml hNUDT5 and 0, 23.8 or 47.5% H218O; the reaction mixture was then incubated for 12 h at 30°C. The 8-oxo-dGDP hydrolysis reaction was carried out under the following conditions: 1.7 mM 8-oxo-dGDP, 57 mM Tris–HCl (pH 9.0), 9.2 mM MgCl2, 28.7 µg/ml hNUDT5 and 0, 23.8 or 47.5% H218O; the reaction mixture was incubated for 2 days at 30°C. The reactions were terminated by adding EDTA to a concentration of 15 mM. Under these conditions, the substrates were almost completely cleaved, which was confirmed by high-performance liquid chromatography. The cleavage of 8-oxo-dGDP was confirmed by using a Wakopak Handy ODS column (4.6 × 250 mm, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd, Osaka, Japan) equilibrated with 0.1 M KH2PO4/K2HPO4 (pH 7.0) and 10% (v/v) methanol. The cleavage of ADPR was confirmed as described previously (36). For 31P NMR analysis, D2O and DSS were added to the reaction mixtures to 10% (v/v) and 0.1 mM, respectively.

NMR experiments were conducted at 25°C on a Varian UnityPlus 500 NMR spectrometer using a 5-mm broadband probe with field/frequency locking on the D2O resonance; 31P chemical shifts were referenced to DSS (0 ppm). One-dimensional 31P NMR spectra were obtained at 202.34 MHz with a spectral width of 25 000 Hz, an acquisition time of 2.56 s, a relaxation delay of 7.44 s and proton decoupling. Each spectrum was collected with 512 scans. Resonances were assigned by comparing reaction spectra to standards of AMP, R5P, 8-oxo-dGMP and sodium phosphate.

RESULTS

Crystal structures of the 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dGMP complexes

The crystal structures of hNUDT5 complexed with substrate 8-oxo-dGDP and Mn2+ ions (hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+) and with the product 8-oxo-dGMP (hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGMP) were obtained at a resolution of 2.1 and 2.3Å, respectively. Both structures contain two hNUDT5 molecules in the asymmetric unit, forming a homodimer related by a non-crystallographic 2-fold axis.

The bound 8-oxo-dGDP adopts a Z-shaped conformation, i.e. the base moiety and the pyrophosphate group point in opposite directions (Figure 2A). The conformation of 8-oxo-dGDP is somewhat unusual high-anti for the glycosidic bond; C2’-endo for the sugar ring; gauche− for the exocyclic C4’–C5’ bond; and gauche+, gauche− and trans for the C5’–O5’, O5’–Pα, and Pα–O bonds, respectively. The 8-oxoG base is sandwiched between Trp28 and Trp46* (residue numbers of another subunit are indicated by asterisks), forming tight-stacking interactions. In addition, the 8-oxoG base is recognized through a number of hydrogen-bonding interactions with hNUDT5. The main chain of Glu47* forms three hydrogen bonds with N1-H, N2-H and O6 of 8-oxoG. The side chain of Arg51 forms a hydrogen bond with N3 of 8-oxoG, and the side and main chains of Thr45* form water-mediated hydrogen bonds with O6 and N7-H of 8-oxoG. However, no direct interaction is observed at N7-H or O8 of 8-oxoG, both of which are characteristic features of 8-oxoG. This observation is consistent with previous reports in which the Km for 8-oxo-dGDP was noted to be only from 9.2- to 3.6-fold lower than that for canonical dGDP (15,17). The difference in Km between 8-oxo-dGDP and dGDP may reflect the different strengths of the stacking interactions with two Trp residues. On the other hand, MutT with high-substrate specificity discriminates 8-oxoG from guanine nucleotides through the N7-H (8-oxoG) ≡ Oδ (Asn119) hydrogen bond, the syn conformation of 8-oxoG nucleotides, and the van der Waals interactions of O8 with the surrounding residues resulted from the ligand-induced conformational change of MutT (11).

Figure 2.

Recognition mechanisms of oxidized nucleotides by hNUDT5. (A) Stereo view of the interactions of the 8-oxo-dGDP and Mn2+ ions with hNUDT5. Residues from the first subunit are shown in blue and the second subunit in gray. The bound 8-oxo-dGDP shown in ball-and-stick representation is colored yellow. Water molecules are shown as red spheres and Mn2+ ions are shown as purple spheres with the electron density from the anomalous difference Fourier map (cyan) contoured at 3.5σ (λ = 1.5Å). Hydrogen bonds are shown as orange dashed lines. (B) Stereo view of the interactions of 8-oxo-dADP and Mn2+ ions with hNUDT5. Residues, Mn2+ ions, and water molecules are shown using the same representation and color scheme as that of (A). The bound 8-oxo-dADP is shown in light pink. The electron density from the anomalous difference Fourier map contoured at 3.5σ (λ = 1.5Å) is shown in cyan.

The recognition of the deoxyribose moiety is rather loose. Arg51 is the only residue involved in deoxyribose recognition, and there is no residue around the C2’ position of the deoxyribose. Such a moderate recognition of the deoxyribose moiety does not allow hNUDT5 to discriminate 8-oxo-GDP from 8-oxo-dGDP (16).

The negative charges of the pyrophosphate group of 8-oxo-dGDP are neutralized by Arg84 and metal ions bound to the negatively charged active site formed mainly by the MutT signature (residues 97–119). In this structure, two Mn2+ ions are observed at one of the two active sites in the hNUDT5 dimer. The positions of the Mn2+ ions were confirmed by the presence of peaks in the anomalous difference Fourier map at λ = 1.5Å (Figure 2A). The first Mn2+ (M1) is coordinated with distorted octahedral geometry by Ala96 and Glu116 of the enzyme, Oα1 and Oβ1 of 8-oxo-dGDP and two water molecules. The second Mn2+ (M2) is coordinated with incomplete geometry by Glu112 and Glu116 of the enzyme, Oβ1 of 8-oxo-dGDP and a water molecule. Although hNUDT5 requires the divalent cations Mg2+, Mn2+ or Zn2+ for catalysis (23), the hydrolysis of 8-oxo-dGDP did not occur under the crystallization condition of pH 6.2 within at least 3 days.

The overall structures of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ and hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGMP are quite similar, with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.78Å over 390 Cα atoms. The binding mode of 8-oxo-dGMP is also identical to that of 8-oxo-dGDP (Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting that the 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dGMP complexes have a ‘pre-catalytic state structure’ and ‘product state structure’, respectively.

Crystal structure of the 8-oxo-dADP complex

To understand the substrate-recognition diversity of hNUDT5 more completely, we also determined the crystal structure of hNUDT5 complexed with 8-oxo-dADP and Mn2+ ions (hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+) at a resolution of 2.05 Å. In this structure, bound 8-oxo-dADP also adopts a Z-shaped conformation (Figure 2B). The conformation of 8-oxo-dADP is high-anti for the glycosidic bond; C2’-endo for the sugar ring; trans for the exocyclic C4’–C5’ bond; and gauche+, gauche+ and gauche+ for the C5’–O5’, O5’–Pα and Pα–O bonds, respectively. The 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroadenine base (8-oxoA) binds to hNUDT5 with a slight rotation in the horizontal direction of the base plane (∼30°) compared to 8-oxoG in hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+. The main chain of Glu47* and the side chain of Arg51 are hydrogen-bonded to N1 and N3 of 8-oxoA, respectively. Except for this hydrogen-bonding scheme, the 8-oxo-dADP recognition mechanism by hNUDT5 is similar to that of 8-oxo-dGDP. When the active site structures are superposed, the most overlapped atom in the two oxidized nucleoside diphosphates is observed to be Pβ.

In this structure, two Mn2+ ions corresponding to M1 and M2 in hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ are also observed at both active sites. Moreover, an additional peak corresponding to a third Mn2+ (M3) in the anomalous difference Fourier map is observed at one active site, although its coordination geometry is incomplete because of the low occupancy of M3 (Figure 2B).

Comparison of the binding mode between 8-oxo-dGDP (8-oxo-dADP) and ADPR

A comparison of protein structures between the 8-oxo-dGDP and ADPR complexes reveals no significant alteration, even in the substrate-binding pockets (RMSD of 0.80Å over 390 Cα atoms). However, surprisingly, the binding modes of 8-oxo-dGDP and ADPR are extremely different.

First, the faces of 8-oxoG in the bound 8-oxo-dGDP are turned over compared with the adenine of ADPR, i.e. the direction of the sugar linkages are observed to be opposite (Figure 3A). This would result from differences in the hydrogen-bonding ability of the pyrimidine rings at the positions of N1, C2 and C6 when forming hydrogen bonds with Glu47*. In 8-oxoG, N1-H and N2-H act as hydrogen-bond donors, while O6 acts as a hydrogen-bond acceptor. On the other hand, in adenine, N1 acts as the acceptor, while N6-H acts as the donor. In general, a key part of nucleotides in recognition by an enzyme is a base moiety. Enzymes which have broad substrate specificity often recognize common elements of the bases. For example, DNA polymerases recognize N3 of purine and O2 of pyrimidine (37). However, we revealed that hNUDT5 achieves broad substrate specificity by an unusual base recognition mechanism as shown in Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the substrate-binding modes among the 8-oxo-dGDP, 8-oxo-dADP and ADPR complexes. (A) 8-oxoG of 8-oxo-dGDP, 8-oxoA of 8-oxo-dADP and adenine of ADPR recognition schemes. The bases are indicated with bold lines, and the residues involved in the base recognition with thin lines. Hydrogen bonds are shown with dashed lines. Water molecules are shown as spheres. (B) Binding modes of ADPR (pale green) with horseshoe conformation. (C) Superposition of the 8-oxo-dGDP and ADPR complexes. The 8-oxo-dGDP complex is colored, and the ADPR complex is shown in gray.

In addition, the differences of the substrate-binding modes are also observed at the pyrophosphate group, which represents the cleavage site in hydrolysis. Unlike 8-oxo-dGDP with a Z-shaped conformation, ADPR adopts a horseshoe conformation (Figure 3B), i.e. the two ends come together as shown in the crystal structures of bacterial ADPRases (E. coli ORF209 [EcORF209], Mycobacterium tuberculosis ADPRase [MtADPRase], Thermus thermophilus Ndx4 [TtNdx4] and T. thermophilus Ndx2 [TtNdx2]) complexed with ADPR or its analog AMPCPR, all of which have overall structures similar to hNUDT5 (38–42). As a result, the positions of the two phosphate groups (α- and β-phosphates) in the substrate observed in the 8-oxo-dGDP complex are completely inverted compared with those observed in the ADPR complex, and the β-phosphorus (Pβ) of 8-oxo-dGDP and the α-phosphorus (Pα) of ADPR are superposed on the same position (Figure 3C). The orientation of the pyrophosphate group in hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+ structure is also the same as that in hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+.

In spite of the differences of substrate-binding modes, the three metal-binding sites observed in hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+ are essentially identical with those in the AMPCPR complex (Supplementary Figure S2). Among these three metals, however, it seems that M1 and M2 are necessary for positioning the pyrophosphate group of 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP, whereas they are not always necessary for ADPR positioning. In the ADPR complex of hNUDT5, only one metal corresponding to M1 is observed. Moreover, the pyrophosphate group of ADPR strictly binds to enzymes without metal coordination in the bacterial ADPRase structures EcORF209, MtADPRase and TtNdx4 (PDB codes: 1G9Q, 1MK1 and 1V8L, respectively) (38,40,42). The terminal ribose of ADPR is buried at the base of the substrate-binding pocket and is stabilized by several hydrogen-bond interactions with hNUDT5 (Supplementary Figure S3), which helps to maintain ADPR in a horseshoe conformation. However, in hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ and hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP-Mn2+, the lack of an X moiety of substrates causes such interactions to be lost and causes high flexibility of the pyrophosphate group. In fact, the crystal structures of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP and hNUDT5-8-oxo-dADP obtained in the absence of metal ions displayed no electron density corresponding to the deoxyribose-pyrophosphate moiety of the substrates (data not shown).

Catalytic mechanism

It has been shown by mutagenic analyses that two glutamic acid residues at the active site Glu112 and Glu116 in the MutT signature play the most important roles in the hydrolysis of ADPR. This is because both of the mutations, E112Q and E116Q, result in a dramatic decrease in kcat (6.3 × 103 and 2.0 × 103, respectively) (25). Glu112 and Glu116 as well as metal-binding sites are structurally conserved among the 8-oxo-dGDP, 8-oxo-dADP and AMPCPR complexes (Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, the active-site architectures of these complexes are essentially identical, suggesting that the residues involved in catalysis would be mostly shared in the hydrolysis of any substrate by hNUDT5.

Based on its crystal structures and mutagenic analyses, Zha et al. (25) have proposed an ADPR hydrolysis-reaction mechanism by hNUDT5. Briefly, Pα of ADPR is attacked by the conserved nucleophilic water that coordinates with two metal ions (a binuclear complex corresponding to M2 and M3 in the 8-oxo-dATP complex) bound to Glu112 and Glu116. Glu166 located at the tip of the flexible loop L9 acts as a general base that deprotonates the conserved water, which is supported by the data that the E166Q mutation of hNUDT5 led to 120-fold decrease in kcat (25). Similar mechanisms have also been proposed for the hydrolysis of ADPR by EcORF209 and MtADPRase (39,40). Active site structures observed in EcORF209 and MtADPRase complexed with AMPCPR (39,40) are very similar to that in hNUDT5 complexed with AMPCPR (25). The evidence that Pα of ADPR is attacked by the nucleophilic water has been confirmed by ADPR hydrolysis experiments of EcORF209 using 18O-labeled water and mass spectra analysis (39). Since the 120-fold decrease of the E166Q mutant in kcat is a small change compared with the 6300- and 2000-fold decreases of the E112Q and E116Q mutants, respectively, the role of Glu166 as a general base is somewhat debatable. This much smaller contribution of Glu166 than of Glu112 and Glu116 to hydrolysis remains to be resolved.

As these results, when considering the hydrolysis of 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP by hNUDT5, we may propose that 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP are attacked at Pβ (corresponding to Pα of ADPR in the enzyme–substrate complex structures) due to the inverse rearrangement of the pyrophosphate group, as described above (Figure 3C).

Determination of the site of nucleophilic substitution

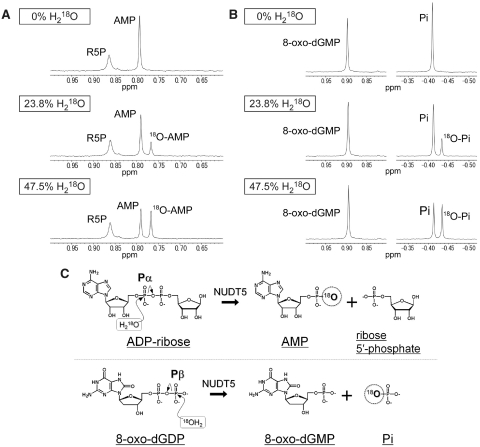

In order to determine the nucleophilic substitution sites for 8-oxo-dGDP and ADPR in hydrolysis reactions, we used the isotope-labeling method. In this method, hydrolysis reactions were carried out for each substrate in the presence of 18O-labeled water. If nucleophilic substitution by an oxygen atom of water occurs at Pα, 8-oxo-dGMP or AMP (as one of the reaction products) would be labeled with 18O. On the other hand, if substitution occurs at Pβ, Pi or R5P (as one of the other reaction products) would be labeled. It has been shown that 18O-labeled reaction products are detectable by a small up-field shift in the 31P NMR spectra (43).

First, we investigated whether or not nucleophilic attack occurs at Pα of ADPR in the hydrolysis by hNUDT5, as established in the case of EcORF209. The proton-decoupled 31P NMR spectra of the ADPR hydrolysis reaction mixtures are shown in Figure 4A. In the absence of H218O, two different resonances at 0.864 and 0.794 ppm were observed, corresponding to R5P and AMP, respectively. When the reaction was carried out in the presence of 23.8 or 47.5% H218O, an additional peak appeared ∼0.02 ppm up-field from the resonance assigned to AMP in a dose-dependent manner. This observation confirmed that ADPR is attacked at Pα, as proposed by Zha et al. (25).

Figure 4.

Proton-decoupled 31P NMR spectra of ADPR or 8-oxo-dGDP hydrolysis reaction mixtures. (A) Products of the ADPR hydrolysis reaction carried out in 0%, 23.8% or 47.5% 18O-labeled water. (B) Products of the 8-oxo-dGDP hydrolysis reaction carried out in 0%, 23.8% or 47.5% 18O-labeled water. (C) Hydrolysis reaction schemes of NUDT5. ADPR is attacked at Pα by nucleophilic water (top), whereas 8-oxo-dGDP is attacked at Pβ (bottom).

Next, the same experiments were performed for the 8-oxo-dGDP hydrolysis reaction. The proton-decoupled 31P NMR spectra of the 8-oxo-dGDP hydrolysis reaction mixtures are shown in Figure 4B. In the absence of H218O, two different resonances at 0.896 and −0.410 ppm were observed, corresponding to 8-oxo-dGMP and Pi, respectively. When the reaction was carried out in the presence of 23.8% or 47.5% H218O, a new peak, corresponding to the 18O-labeled Pi, appeared. This observation clearly indicates that 8-oxo-dGDP is attacked at Pβ, in contrast to ADPR (Figure 4C). We also confirmed that hNUDT5 hydrolyzes dGDP to dGMP through the nucleophilic attack at Pβ by the same method (Supplementary Figure S4). The nucleophilic substitution at Pβ has been also observed in hydrolyses of dGTP by MutT (44) and 8-oxo-dGTP by hMTH1 (45).

It is known that the mechanisms of Nudix hydrolases are highly diverse regarding the position on the substrate at which the substitution occurs. However, it is the first example where a single enzyme catalyzes nucleophilic substitutions by water at the chemically un-equivalent phosphorus atoms on the substitutes among Nudix hydrolases.

Structural comparison of hNUDT5 and E. coli MutT

The structure of E. coli MutT complexed with 8-oxo-dGMP and Mn2+ (MutT-8-oxo-dGMP-Mn2+) has been reported as the first crystal structure of the Nudix hydrolase complexed with the 8-oxoG-containing nucleotide (11). When comparing the structures of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ and MutT-8-oxo-dGMP-Mn2+, the C-terminal region of hNUDT5 is similar to the overall structure of MutT (Figure 5A). However, since hNUDT5 has an additional N-terminal region which is involved in base recognition as well as dimerization, the positions of 8-oxoG bases and sugars of the two 8-oxoG-containing nucleotides are completely different between both structures (Figure 5B). Nevertheless, the positions of the α-phosphate groups of them are essentially identical, and active site residues are structurally conserved between both enzymes, especially at the MutT signature region. The only Mn2+ ion found in MutT-8-oxo-dGMP-Mn2+ is located at the position similar to M1 in hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+. In addition, Pβ of dGTP is attacked by the nucleophilic water in the hydrolysis reaction by MutT (44). Judging from these results, when 8-oxo-dGTP binds to MutT, the position of the β-phosphate group would also be identical to that of the β-phosphate group observed in hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+.

Figure 5.

Structural comparisons between hNUDT5 and E. coli MutT. (A) Superposition of hNUDT5-8-oxo-dGDP-Mn2+ and MutT-8-oxo-dGMP-Mn2+ (PDB code: 3A6U). hNUDT5 is a dimer enzyme; one protomer is shown in blue, the other one in gray and the MutT signature region is shown in magenta. 8-oxo-dGDP and Mn2+ ions bound to hNUDT5 are shown as yellow sticks and purple spheres, respectively. MutT is a monomer enzyme and shown in light orange. 8-oxo-dGMP and Mn2+ bound to MutT are shown as cyan sticks and light orange spheres, respectively. (B) Enlarged view of the active sites. The pyrophosphate group binding site is shown as light blue ellipse.

DISCUSSION

Substrate-conformation selectivity

In the present study, we have clearly documented the difference in nucleophilic substitution sites between 8-oxo-dGDP and ADPR in hydrolysis reactions by hNUDT5 despite the similarities in the chemical structures of the substrates and products. The isotope-labeling method has confirmed that 8-oxo-dGDP is attacked at Pβ, while ADPR is attacked at Pα. The nucleophilic substitution sites of substrates vary by the overall conformation of substrates; that is, a Z-shaped conformation and a horseshoe conformation would have different substitution sites. The overall conformation of bound substrates may be affected by the orientation of their base moieties. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the bases of substrates are strictly fixed through a combination of stacking interactions and several hydrogen-bonding interactions in the crystal structures. The binding orientation of the adenine base in ADPR is quite different from that of the bases in oxidized nucleotides, and as a result, the adenosyl ribose of ADPR faces the solvents. Thus, ADPR never adopts a Z-shaped conformation.

The pyrimidine moiety of 8-oxo-dADP has the same chemical property as adenine, which involves N1 and N6 in hydrogen bonds when ADPR is bound to hNUDT5. However, we observed that the bases bind with different orientations (Figure 3A); when we tried modeling 8-oxo-dADP bound to the enzyme in the same manner as ADPR, steric hindrance between O8 of 8-oxoA and O4’ of deoxyribose, as well as unfavorable contacts between N7-H and the guanidinium group of Arg51, occurred. Therefore, 8-oxo-dADP could not adopt a horseshoe conformation.

Moreover, when we tried to build models in which 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP adopted a horseshoe conformation without changing the orientations of their bases, the α-phosphate group of both substrates (of which Pα was the putative nucleophilic substitution site instead of Pβ in this case) could not be positioned in an appropriate orientation for catalysis, resulting in the disruption of metal coordination or distortion of nucleotide conformations. Hence, both 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP bound to hNUDT5 and Mn2+ prefer to adopt the Z-shaped conformation.

Substrate affinities and reaction rates

It has been reported that hNUDT5 exhibits from ∼8- to 40-fold lower Km values for 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP than for ADPR (15,17,23). The kcat value for 8-oxo-dADP is ∼1300-fold lower than that for ADPR (17,25). The reaction rates for other X-lacking substrates are comparable to or slower than that for 8-oxo-dADP (15,17). Furthermore, recently we have found that the 8-oxo-dGDPase and ADPRase activities associated with NUDT5 exhibit different pH preferences. The optimum pH for cleavage of ADPR is pH 7–9 while that for 8-oxo-dGDPase is around pH 10 and the kcat value of 8-oxo-dGDPase is ∼50-fold lower than that of ADPRase at their optimum pHs. And also it has been found that the 8-oxo-dGDP cleavage by NUDT5 was competitively inhibited by ADPR and its reaction product, AMP, and, in reverse, the cleavage of ADPR is inhibited by 8-oxo-dGDP (46). These facts indicate that the affinity of hNUDT5 for the oxidized nucleoside diphosphates tends to be higher than its affinity for ADPR, whereas the reaction rates for the oxidized nucleotides are considerably slower as compared to that for ADPR in vitro, then, there arises the question if hydrolysis of 8-oxo-dGDP by NUDT5 is important physiologically. However, as already mentioned, the evidences indicated by in vivo studies using E. coli mutT− cells and hNUDT5-knocked-down cells support the answer that NUDT5 is functional in vivo to eliminate mutagenic and oxidized nucleotides from the DNA precursor pool, that is, NUDT5 catalyzes the hydrolysis of 8-oxo-dGDP in the cells.

The overall conformation of the bound ADPR is anti for the glycosidic bond, C3’-endo for the sugar ring, gauche− for the exocyclic C4’–C5’ bond, and trans, gauche− and gauche- for the C5’–O5’, O5’–Pα and Pα–O bonds, respectively. Through interactions of the terminal ribose of ADPR with hNUDT5, the phosphorus atom (Pα) attacked by the nucleophilic water molecule can be easily fixed at the proper position for catalysis. On the other hand, the bound 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP adopt rather unusual conformations. Although electron densities corresponding to deoxyribose moieties are somewhat ambiguous, the densities corresponding to 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP are best fitted to the Z-shaped overall conformations (Supplementary Figure S5). Because 8-substituted purine nucleosides and 5’-nucleotides prefer to adopt the syn conformation, the high-anti conformation in the Z-shaped structure might be unstable for 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP (47). In addition to the lack of an X moiety, such an unfavorable conformation makes it relatively difficult to fix the phosphorus atom (Pβ) attacked by the nucleophilic water at the proper position for catalysis. Thus, hNUDT5 exhibits much slower reaction rates for both 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP than that for ADPR.

The differences in substrate affinity exhibited by hNUDT5 may, to some extent, be explained in terms of the strength of the stacking interactions at base moieties (48). As mentioned above, the base moieties of substrates are sandwiched by two Trp residues (Trp28 and Trp46*), forming π–π stacking interactions. Substrate affinities tend to decrease with decreasing numbers of substitution groups at the base moiety. For example, the Km value of hNUDT5 for 8-oxo-dGDP is lower than that for dGDP (0.77 versus 7.1 µM, or 2.1 versus 7.6 µM) which is expected to bind in a similar manner as 8-oxo-dGDP because their nucleophilic substitution sites in hydrolysis are identical (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S4) (15,17). The Km value for 8-oxo-dADP is also lower than that for dADP (2.9 versus 12.6 µM) (17). Thus, hNUDT5 may discriminate oxidized nucleotides from canonical nucleotides (48). Intriguingly, the two Trp residues (Trp28 and Trp46 of hNUDT5) are not conserved among the prokaryotic ADPRases but highly conserved among the putative eukaryotic ADPRases (function-unknown NUDT5 homologues, Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S6). The two Trp residues seem to greatly contribute in binding and hydrolysis reaction of oxidized nucleotides with relatively unstable Z-shaped conformation by hNUDT5. Hence, although hNUDT5 is the only known enzyme hydrolyzing oxidized nucleotides among the ADPRase subfamily members so far, these eukaryotic homologues may also be able to bind to and hydrolyze oxidized nucleotides with Z-shaped conformation. In addition, these eukaryotic species also have a MTH1 homolog. Considering these facts, the oxidized nucleotide eliminating system by the two Nudix hydrolases (NUDT5 homolog and MTH1 homolog) might have been established at the early stage of evolution.

Figure 6.

Sequence alignment of N-terminal region of eukaryotic and prokaryotic ADPRases. Sequences shown here are as follows: Human (NUDT5 [NP_054861]), Danio rerio (NP_001002086), Micromonas sp. (XP_002504390), Tetrahymena thermophila (XP_001010705), E. coli (ORF209 [NP_417506]), M. tuberculosis (MtADPRase [NP_216216]) and T. thermophilus HB8 (Ndx4 [YP_143794], Ndx2 [YP_144129]). The conserved tryptophan residues are boxed with black background. The structural alignment for the proteins of known structure was calculated with MATRAS, and sequence alignment was prepared with Clustal W (49,50).

CONCLUSIONS

Although at least the pyrophosphate moieties of all substrates were believed to bind to hNUDT5 in a similar manner as ADPR, the crystal structures of the 8-oxo-dGDP and 8-oxo-dADP complexes presented here illustrate unexpected binding modes. In addition, 31P NMR analysis clearly showed the difference in nucleophilic substitution sites between 8-oxo-dGDP and ADPR hydrolysis reactions; this finding indicates that our crystal structures simulate an enzymatic process in solution. As a result, we have provided the structural basis for the diverse recognition of substrates exhibited by hNUDT5 and a unique catalytic mechanism. To our knowledge, this investigation is the first to report that an enzyme catalyzes nucleophilic attacks to chemically un-equivalent atoms of substrates with similar chemical structures. Although it is generally believed that enzymes use similar mechanisms when catalyzing reactions of substrates that possess similar chemical structures, our data contradicts this assumption. Therefore, we propose that it is necessary to determine 3D structures of each enzyme-substrate (or analog) complex in an effort to understand more completely the complexities of enzymology.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

(PDB) 3L85, 3AC9, 3ACA.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan. Funding for open access charge: Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Y.Y.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Sciences and Technology of Japan.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the staff of SPring-8 and Photon Factory, Japan for assistance with X-ray data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuchino Y, Mori F, Kasai H, Inoue H, Iwai S, Miura K, Ohtsuka E, Nishimura S. Misreading of DNA templates containing 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine at the modified base and at adjacent residues. Nature. 1987;327:77–79. doi: 10.1038/327077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moriya M, Ou C, Bodepudi V, Johnson F, Takeshita M, Grollman A. Site-specific mutagenesis using a gapped duplex vector: a study of translesion synthesis past 8-oxodeoxyguanosine in E. coli. Mutat. Res. 1991;254:281–288. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90067-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shibutani S, Takeshita M, Grollman A. Insertion of specific bases during DNA synthesis past the oxidation-damaged base 8-oxodG. Nature. 1991;349:431–434. doi: 10.1038/349431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maki H, Sekiguchi M. MutT protein specifically hydrolyses a potent mutagenic substrate for DNA synthesis. Nature. 1992;355:273–275. doi: 10.1038/355273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satou K, Kawai K, Kasai H, Harashima H, Kamiya H. Mutagenic effects of 8-hydroxy-dGTP in live mammalian cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;42:1552–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satou K, Hori M, Kawai K, Kasai H, Harashima H, Kamiya H. Involvement of specialized DNA polymerases in mutagenesis by 8-hydroxy-dGTP in human cells. DNA Repair. 2009;8:637–642. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayakawa H, Taketomi A, Sakumi K, Kuwano M, Sekiguchi M. Generation and elimination of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine 5'-triphosphate, a mutagenic substrate for DNA synthesis, in human cells. Biochemistry. 1995;34:89–95. doi: 10.1021/bi00001a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito R, Hayakawa H, Sekiguchi M, Ishibashi T. Multiple enzyme activities of Escherichia coli MutT protein for sanitization of DNA and RNA precursor pools. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6670–6674. doi: 10.1021/bi047550k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taddei F, Hayakawa H, Bouton M, Cirinesi A, Matic I, Sekiguchi M, Radman M. Counteraction by MutT protein of transcriptional errors caused by oxidative damage. Science. 1997;278:128–130. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura T, Doi T, Sekiguchi M, Yamagata Y. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of Escherichia coli MutT in binary and ternary complex forms. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:1641–1643. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904016403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura T, Meshitsuka S, Kitagawa S, Abe N, Yamada J, Ishino T, Nakano H, Tsuzuki T, Doi T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Structural and dynamic features of the MutT protein in the recognition of nucleotides with the mutagenic 8-oxoguanine base. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:444–452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujikawa K, Kamiya H, Yakushiji H, Fujii Y, Nakabeppu Y, Kasai H. The oxidized forms of dATP are substrates for the human MutT homologue, the hMTH1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:18201–18205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujikawa K, Kamiya H, Yakushiji H, Nakabeppu Y, Kasai H. Human MTH1 protein hydrolyzes the oxidized ribonucleotide, 2-hydroxy-ATP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:449–454. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.2.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mo J, Maki H, Sekiguchi M. Hydrolytic elimination of a mutagenic nucleotide, 8-oxodGTP, by human 18-kilodalton protein: sanitization of nucleotide pool. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:11021–11025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.11021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishibashi T, Hayakawa H, Sekiguchi M. A novel mechanism for preventing mutations caused by oxidation of guanine nucleotides. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:479–483. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishibashi T, Hayakawa H, Ito R, Miyazawa M, Yamagata Y, Sekiguchi M. Mammalian enzymes for preventing transcriptional errors caused by oxidative damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3779–3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamiya H, Hori M, Arimori T, Sekiguchi M, Yamagata Y, Harashima H. NUDT5 hydrolyzes oxidized deoxyribonucleoside diphosphates with broad substrate specificity. DNA Repair. 2009;8:1250–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bialkowski K, Kasprzak K. A novel assay of 8-oxo- 2′-deoxyguanosine 5'-triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase (8-oxo-dGTPase) activity in cultured cells and its use for evaluation of cadmium(II) inhibition of this activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3194–3201. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.13.3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hori M, Satou K, Harashima H, Kamiya H. Suppression of mutagenesis by 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine 5′-triphosphate (7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine 5′-triphosphate) by human MTH1, MTH2, and NUDT5. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48:1197–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassa P, Haenni S, Elser M, Hottiger M. Nuclear ADP-ribosylation reactions in mammalian cells: where are we today and where are we going? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006;70:789–829. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson E, Cervantes-Laurean D, Jacobson M. Glycation of proteins by ADP-ribose. Mol. Cell Biochem. 1994;138:207–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00928463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasmi L, Cartwright J, McLennan A. Cloning, expression and characterization of YSA1H, a human adenosine 5′-diphosphosugar pyrophosphatase possessing a MutT motif. Biochem. J. 1999;344:331–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang H, Slupska M, Wei Y, Tai J, Luther W, Xia Y, Shih D, Chiang J, Baikalov C, Fitz-Gibbon S, et al. Cloning and characterization of a new member of the Nudix hydrolases from human and mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:8844–8853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zha M, Zhong C, Peng Y, Hu H, Ding J. Crystal structures of human NUDT5 reveal insights into the structural basis of the substrate specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;364:1021–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zha M, Guo Q, Zhang Y, Yu B, Ou Y, Zhong C, Ding J. Molecular mechanism of ADP-ribose hydrolysis by human NUDT5 from structural and kinetic studies. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:568–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bessman M, Frick D, O'Handley S. The MutT proteins or “Nudix” hydrolases, a family of versatile, widely distributed, “housecleaning” enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:25059–25062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S, Mura C, Sawaya M, Cascio D, Eisenberg D. Structure of a Nudix protein from Pyrobaculum aerophilum reveals a dimer with two intersubunit beta-sheets. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:571–578. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902001191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coseno M, Martin G, Berger C, Gilmartin G, Keller W, Doublié S. Crystal structure of the 25 kDa subunit of human cleavage factor Im. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3474–3483. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brünger A, Adams P, Clore G, DeLano W, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R, Jiang J, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams P, Gopal K, Grosse-Kunstleve R, Hung L, Ioerger T, McCoy A, Moriarty N, Pai R, Read R, Romo T, et al. Recent developments in the PHENIX software for automated crystallographic structure determination. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 2004;11:53–55. doi: 10.1107/s0909049503024130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murshudov G, Vagin A, Dodson E. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storoni L, McCoy A, Read R. Likelihood-enhanced fast rotation functions. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:432–438. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabsch W. A solution for the best rotation to relate two sets of vectors. Acta. Crystallogr. A. 1976;32:922–923. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ooga T, Yoshiba S, Nakagawa N, Kuramitsu S, Masui R. Molecular mechanism of the Thermus thermophilus ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase from mutational and kinetic studies. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9320–9329. doi: 10.1021/bi050078y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doublié S, Tabor S, Long A, Richardson C, Ellenberger T. Crystal structure of a bacteriophage T7 DNA replication complex at 2.2 A resolution. Nature. 1998;391:251–258. doi: 10.1038/34593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabelli S, Bianchet M, Bessman M, Amzel L. The structure of ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase reveals the structural basis for the versatility of the Nudix family. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:467–472. doi: 10.1038/87647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabelli S, Bianchet M, Ohnishi Y, Ichikawa Y, Bessman M, Amzel L. Mechanism of the Escherichia coli ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase, a Nudix hydrolase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9279–9285. doi: 10.1021/bi0259296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang L, Gabelli S, Cunningham J, O'Handley S, Amzel L. Structure and mechanism of MT-ADPRase, a nudix hydrolase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Structure. 2003;11:1015–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wakamatsu T, Nakagawa N, Kuramitsu S, Masui R. Structural basis for different substrate specificities of two ADP-ribose pyrophosphatases from Thermus thermophilus HB8. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:1108–1117. doi: 10.1128/JB.01522-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshiba S, Ooga T, Nakagawa N, Shibata T, Inoue Y, Yokoyama S, Kuramitsu S, Masui R. Structural insights into the Thermus thermophilus ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase mechanism via crystal structures with the bound substrate and metal. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37163–37174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohn M, Hu A. Isotopic (18O) shift in 31P nuclear magnetic resonance applied to a study of enzyme-catalyzed phosphate–phosphate exchange and phosphate (oxygen)–water exchange reactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1978;75:200–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber D, Bhatnagar S, Bullions L, Bessman M, Mildvan A. NMR and isotopic exchange studies of the site of bond cleavage in the MutT reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16939–16942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mishima M, Sakai Y, Itoh N, Kamiya H, Furuichi M, Takahashi M, Yamagata Y, Iwai S, Nakabeppu Y, Shirakawa M. Structure of human MTH1, a Nudix family hydrolase that selectively degrades oxidized purine nucleoside triphosphates. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33806–33815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito R, Sekiguchi M, Setoyama D, Nakatsu Y, Yamagata Y, Hayakawa H. Cleavage of oxidized guanine nucleotide and ADP-ribose by human NUDT5 protein. J. Biochem. 2011;149:731–738. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uesugi S, Ikehara M. Carbon-13 magnetic resonance spectra of 8-substituted purine nucleosides. Characteristic shifts for the syn conformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:3250–3253. doi: 10.1021/ja00452a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fromme J, Banerjee A, Huang S, Verdine G. Structural basis for removal of adenine mispaired with 8-oxoguanine by MutY adenine DNA glycosylase. Nature. 2004;427:652–656. doi: 10.1038/nature02306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson J, Higgins D, Gibson T. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawabata T. MATRAS: a program for protein 3D structure comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3367–3369. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.