In overweight/obese adolescents with PCOS, 6 months treatment with rosiglitazone is superior to drospirenone/ethinyl-estradiol in improving metabolic profile, and effective but inferior in attenuating hyperandrogenemia.

Abstract

Context:

Adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have insulin resistance and higher rates of the metabolic syndrome.

Objective:

Our objective was to compare the effects of 6 months treatment with drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol (EE) (3 mg/30 μg) vs. rosiglitazone (4 mg) daily on the hormonal and cardiometabolic profiles of overweight/obese adolescents with PCOS.

Design:

We conducted a randomized, double-blinded, parallel clinical trial in an academic hospital, with n = 46 patients.

Outcome Measures:

The primary outcome measure was insulin sensitivity, hepatic with [6,6-2H2]glucose and peripheral with a 3-h hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp. Other outcome measures included plasma androgen profile and response to ACTH stimulation, glucose and insulin response to oral glucose tolerance test, insulin secretion with a 2-h hyperglycemic clamp, fasting lipid profile, inflammatory markers, intima media thickness, aortic pulse wave velocity, body composition by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, and abdominal adiposity by computed tomography scan.

Results:

Drospirenone/EE resulted in greater reductions in androgenemia. Neither treatment led to change in weight or body mass index, but rosiglitazone led to a significant decrease in visceral adiposity. Compared with drospirenone/EE, treatment with rosiglitazone improved hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity and lowered fasting and stimulated insulin levels during the oral glucose tolerance test. Treatment with drospirenone/EE was associated with elevations in total cholesterol, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and leptin concentrations, whereas treatment with rosiglitazone led to lower triglycerides and higher adiponectin concentrations. Neither treatment affected intima media thickness or pulse wave velocity.

Conclusions:

In overweight/obese adolescents with PCOS, 6 months treatment with rosiglitazone was superior to drospirenone/EE in improving the cardiometabolic risk profile, and effective but inferior in attenuating hyperandrogenemia. Additional studies are needed to test insulin sensitizers in the treatment of the reproductive and cardiometabolic aspects of PCOS.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder among women in the reproductive age group with a prevalence of 6–8% (1–3) and a considerable economic burden (4). Besides being a reproductive disorder characterized by androgen excess, it is also a metabolic disorder characterized by insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia and dysmetabolic syndrome (5–7). Young women and adolescents with this condition are at high risk of developing prediabetes, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and the metabolic syndrome (6–10). Obesity is also widespread among these girls with a predilection toward abdominal adiposity and increased visceral fat (7, 11). Insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia is believed to play a pivotal role in the development of the PCOS associated metabolic disturbances (10, 12). We previously demonstrated that obese adolescents with PCOS have an approximately 50% reduction in peripheral insulin sensitivity with evidence of hepatic insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia compared with equally obese control girls (8). In addition, PCOS adolescents with prediabetes have evidence of β-cell impairment (12), with rapid progression to type 2 diabetes (13). The realization that PCOS is not only a reproductive but also a metabolic disorder starting early in adolescence, and with long-term health implications (7–9), necessitates that therapeutic options target the hormonal and the metabolic disturbances (14). The conventional treatment of PCOS is oral contraceptives (OCPs) and antiandrogenic agents. Although OCPs are effective in attenuating hyperandrogenemia, they have been reported to worsen lipid profile (15, 16), increase inflammatory markers (15), and decrease insulin sensitivity in some studies (17) but not others (18). On the other hand, insulin sensitizers such as metformin have been used successfully in adolescent PCOS with promising results on both the reproductive and the cardiometabolic aspects (14, 15, 19). The thiazolidinediones (TZDs), a class of potent hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin sensitizers (20, 21), have shown promising hormonal and metabolic effects in women with PCOS (22–25). However, they have been associated with weight gain in adults (26) and have not been studied in adolescents. In this randomized double-blinded clinical trial we compared the effects of 6 months treatment with drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol (EE) vs. rosiglitazone on the hormonal, metabolic, and cardiovascular profiles among overweight/obese adolescents with PCOS (www.clinicaltrials.gov; NLM identifier NCT00640224). We hypothesized that treatment with either agent will result in attenuation of the hyperandrogenemia and improvement of menstrual cycles, but rosiglitazone will additionally lead to improvement in insulin sensitivity and cardiometabolic profile, whereas treatment with drospirenone/EE will worsen these parameters.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Overweight/obese patients with PCOS were recruited from the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh (CHP) PCOS center and the community through advertisements and flyers posted in the medical campus and in pediatricians' offices. The diagnosis of PCOS was made as before (8, 12, 19) based on the presence of clinical signs and symptoms of hyperandrogenism and/or biochemical hyperandrogenemia, oligoovulation, and the exclusion of secondary etiologies as per the National Institutes of Health 1990 definition (27). Inclusion criteria were 1) PCOS diagnosis as above, 2) body mass index (BMI) at or above the 85th percentile for age and gender, 3) age 10–20 yr, 4) postmenarche, Tanner stage III–V. Exclusion criteria included 1) existing systemic or psychiatric diseases, 2) preexisting treatment for PCOS, 3) previous thrombotic event, 4) pregnancy, and 5) treatment with medications that impact carbohydrate or lipid metabolism or cardiovascular profile within 4 months of the study. Criteria for withdrawal from the study were 1) pregnancy, 2) use of medications that affect carbohydrate metabolism, and 3) noncompliance with study protocol. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh. Informed consents and assents were obtained from each participant and their legal guardians.

Experimental design

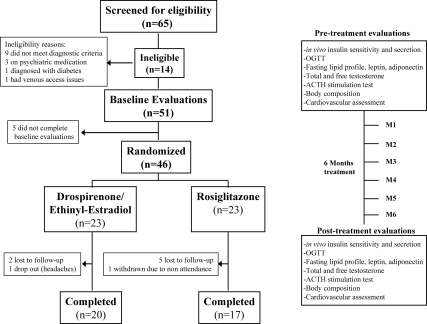

After completing baseline evaluations, patients were randomized to receive double-blinded treatment with either drospirenone 3 mg/EE 30 μg (Yasmin), with a 28-d cycle (21 hormone pills followed by seven placebo pills) or rosiglitazone (Avandia), 4 mg daily. Study medications were prepared by a CHP pharmacist; pills were similarly coated and provided in a 28-d container. Randomization was computer generated by a third party. Patients, their parents, and the investigators were blinded to the intervention until study completion. Each participant was evaluated at baseline and after 6 months of treatment as well as monthly for pill count, side effects evaluation, and urine pregnancy testing. Patients were instructed to continue with their routine dietary and physical activity habits, to use alternative methods of contraception should they be sexually active, and to notify the study coordinator about any medication intake. Procedures are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Summary of study flow and procedures. All procedures were performed at the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center at CHP.

Procedures

Oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT)

After an overnight fast, participants underwent a standard OGTT (1.75 g/kg, maximum 75 g), with samples obtained at −15, 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min for glucose and insulin determination. A fasting blood sample was obtained for total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), very-low-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, adiponectin, leptin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and morning testosterone profile [total testosterone, free testosterone, and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG)] measurements.

ACTH stimulation test

Immediately after completion of the OGTT, participants underwent a Cortrosyn stimulation test (250 μg Cortrosyn IV). Samples were obtained at baseline and at 30 min for measurement of androstenedione, 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHProg), 17-hydroxypregnenolone (17-OHPreg), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS).

Clamp studies

The 3-h hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp and the 2-h hyperglycemic clamp tests were performed on all participants within a 1- to 4-wk period, in random order, and after a 10- to 12-h overnight fast as reported before (12).

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp

Fasting endogenous hepatic glucose production was measured with a primed (2.2 μmol/kg) constant-rate infusion of [6, 6-2H2]glucose (Isotech, Miamisburg, OH) from 0730–0930 h, as described by us previously (28). Blood was sampled at the start of the stable isotope infusion (−120 min) and every 10 min from −30 to 0 min (basal period) for determination of plasma glucose, insulin, and isotopic enrichment of glucose.

After the 2-h baseline isotope infusion period, insulin-mediated glucose metabolism and in vivo insulin sensitivity were measured during a 3-h hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp from 0930–1230 h. Intravenous crystalline insulin (Humulin Regular; Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) was infused at a constant rate of 80 μ/m2 · min, and plasma glucose was clamped at 100 mg/dl with a variable rate infusion of 20% dextrose as reported before (12).

Hyperglycemic clamp

First- and second-phase insulin secretion was assessed during a 2-h hyperglycemic clamp (225 mg/dl), and first- and second-phase glucose and insulin concentrations were measured as before (12).

Calculations

Fasting hepatic glucose production was calculated during the last 30 min of the 2-h isotope infusion (−30 to 0 min) according to steady-state tracer dilution equations (12). Insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rate was calculated during the last 30 min of the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp to be equal to the rate of exogenous glucose infusion. Peripheral insulin sensitivity was calculated by dividing the glucose disposal rate by the steady-state clamp insulin level multiplied by 100 (12). During the hyperglycemic clamp, the first- and second-phase insulin concentrations and the disposition index were calculated as described by us (12).

Biochemical measurements

Plasma glucose was measured with a glucose analyzer (Yellow Springs Instrument Co., Yellow Springs, OH) and insulin, leptin, and adiponectin by RIA (29). Lipids were measured using the standards of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (28), and non-HDL cholesterol was calculated. Total testosterone, 17-OHProg, 17-OHPreg, androstenedione, and DHEAS were measured by HPLC-tandem mass spectroscopy (Esoterix Inc., Calabasas Hills, CA). Free testosterone was measured by equilibrium dialysis, SHBG by immunoradiometric assay, and DHEAS by RIA in dilute serum after hydrolysis (Esoterix Inc., Calabasas Hills, CA), hs-CRP was measured by COAG-Nephelometry [Esoterix Inc., (formerly Colorado Coagulation) Englewood, CO]. All samples, except glucose, were stored at −80 C until study completion. Pre- and posttreatment samples were run in the same assay for each subject. Deuterium enrichment of glucose in the plasma was determined on a Hewlett-Packard Co. (Palo Alto, CA) 5973 mass spectrometer coupled to a 6890 gas chromatograph as reported by us (8).

Body composition

Body composition was determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. A single transverse image of the abdomen (L4–L5) was obtained by computed tomography to determine sc abdominal adipose tissue and visceral adipose tissue (VAT).

Blood pressure determination

Blood pressure was measured when the subjects were resting in the supine position, with an automated sphygmomanometer every 10 min for 1 h from 2200–2300 h before the subject fell asleep and from 0600–0700 h before awakening. The mean of seven measurements during each hour was the outcome for statistical analysis as reported before (12).

Aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV) and intima media thickness (IMT)

PWV, a measure of arterial stiffness, and IMT (right and left carotid arteries) were measured at the Ultrasound Research Laboratory of the Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, by high-resolution B-mode and Doppler ultrasonography, respectively (30).

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the patients in the two groups were compared using independent t tests. In each treatment arm, pre- and posttreatment outcomes were compared using paired t tests. A repeated-measures general linear model with treatment as the between-subject effect and the visit (pretreatment, posttreatment) as the within-subject effect was used to evaluate the differences in response to each treatment. The interaction among the within-subject and between-subject effects, which represents the differential effect of the drug over time, is reported (P treatment × time). Because nine subjects dropped out, analyses obtained from the completers were confirmed using intent-to-treat analysis. The study was powered using our previous data (19) to detect around 40% difference (equal to 1.13 mg/kg · min per μU/ml) in peripheral insulin sensitivity at the end of the trial between the two groups with 80% power and a two sided α of 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± sem. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Bonferroni correction was applied to the secondary outcomes to correct for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (18th edition; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Subjects

The study was conducted from September 2005 to July 2010. Sixty-five adolescents with possible PCOS consented to participate. Of those, 14 were ineligible and five did not complete the baseline evaluations. Forty-six subjects were randomized to receive drospirenone/EE or rosiglitazone. Nine subjects (three in the drospirenone/EE group and six in the rosiglitazone group) did not complete the study for reasons listed in Fig. 1. The dropout rates in the two arms were not statistically different. Participants tolerated the medications well with no notable side effects. Age, race, weight, and BMI were not different between subjects who dropped out and those who completed the study (data not shown). Table 1 depicts pre- and posttreatment characteristics of PCOS adolescents who completed the study treatment arms. Before treatment, there were no significant differences in age, race, weight, BMI, BMI percentile, waist circumference, or body composition between the two study arms. All study participants were Tanner stage V.

Table 1.

Pre- and posttreatment demographic, body composition, hormonal, and cardiometabolic characteristics of the study participants

| Drospirenone/EE |

Pa | Rosiglitazone |

Pa | Pb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 20) | 6 months (n = 20) | Baseline (n = 17) | 6 months (n = 17) | ||||

| AA/C/biracial (n) | 3/15/2 | 3/15/2 | 4/9/4 | 4/9/4 | NSc | ||

| Age (yr) | 16.2 ± 0.3 | 16.7 ± 0.3 | <0.001 | 15.7 ± 0.3 | 16.3 ± 0.3 | <0.001 | NS |

| Weight (kg) | 102.1 ± 4.9 | 101.5 ± 5.1 | NS | 97.0 ± 4.3 | 97.3 ± 4.4 | NS | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 37.5 ± 1.7 | 37.4 ± 1.8 | NS | 35.6 ± 1.5 | 35.7 ± 1.6 | NS | NS |

| BMI (%ile) | 97.7 ± 0.4 | 97.0 ± 0.7 | NS | 97.2 ± 0.4 | 96.8 ± 0.7 | NS | NS |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 104.8 ± 4.5 | 106.9 ± 4.0 | NS | 101.9 ± 3.5 | 101.2 ± 3.7 | NS | NS |

| Fat mass (kg) | 48.0 ± 3.2 | 49.1 ± 3.4 | NS | 44.5 ± 2.8 | 45.4 ± 3.4 | NS | NS |

| % body fat | 47.3 ± 1.1 | 48.2 ± 1.2 | NS | 46.2 ± 1.1 | 46.6 ± 1.6 | NS | NS |

| VAT (cm2) | 71.1 ± 7.3 | 77.2 ± 8.4 | NS | 67.8 ± 4.7 | 60.8 ± 4.8 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| SAT (cm2) | 594.1 ± 49.6 | 600.4 ± 48.0 | NS | 571.3 ± 44.1 | 576.2 ± 44.1 | NS | NS |

| VAT/SAT ratio | 0.126 ± 0.02 | 0.133 ± 0.01 | NS | 0.124 ± 0.01 | 0.110 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.003d |

| Androgen profile | |||||||

| Free testosterone (pg/ml) | 7.5 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | <0.001d | 10.7 ± 2.0 | 7.7 ± 1.6 | 0.002d | 0.04 |

| Total testosterone (ng/dl) | 34.5 ± 3.2 | 30.6 ± 3.1 | NS | 45.7 ± 5.6 | 36.9 ± 3.7 | 0.04 | NS |

| % free testosterone | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | <0.001d | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 0.02 | <0.001d |

| SHBG (nmol/liter) | 22.7 ± 2.2 | 154.5 ± 24.0 | <0.001d | 28.1 ± 4.6 | 37.0 ± 6.6 | 0.01 | <0.001d |

| DHEAS (μg/dl) | 212.2 ± 25.4 | 197.5 ± 25.6 | NS | 165.4 ± 17.0 | 160.9 ± 17.9 | NS | NS |

| ACTH stimulation test | |||||||

| Δ Androstenedione (ng/dl) | 82.6 ± 10.6 | 117.0 ± 18.2 | NS | 79.2 ± 11.5 | 58.4 ± 9.5 | NS | 0.06 |

| Δ DHEA (ug/dl) | 1001.6 ± 183.1 | 1092.1 ± 188.4 | NS | 817.4 ± 119.5 | 643.4 ± 102.4 | NS | NS |

| Δ 17-OHProg (ng/dl) | 169.8 ± 37.3 | 175.4 ± 46.5 | NS | 207.0 ± 37.4 | 178.0 ± 49.1 | NS | NS |

| Δ 17-OHPreg (ng/dl) | 1024.3 ± 114.5 | 1088.9 ± 161.0 | NS | 912.8 ± 92.1 | 914.7 ± 110.9 | NS | NS |

| Metabolic/cardiovascular profile | |||||||

| NGT (n) | 12 | 13 | 15 | 15 | |||

| IGT (n) | 8 | 7 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 92.3 ± 1.5 | 92.6 ± 1.9 | NS | 96.0 ± 1.7 | 95.0 ± 1.4 | NS | NS |

| Fasting insulin (μU/ml) | 34.9 ± 3.7 | 35.5 ± 4.4 | NS | 32.8 ± 3.2 | 24.9 ± 3.2 | 0.001d | 0.03 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 156.5 ± 6.9 | 185.2 ± 9.1 | <0.001d | 149.5 ± 8.1 | 146.2 ± 7.9 | NS | 0.001d |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 40.9 ± 1.9 | 55.0 ± 2.8 | <0.001d | 42.7 ± 3.0 | 46.1 ± 2.1 | NS | 0.005d |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 85.9 ± 6.2 | 97.7 ± 7.4 | 0.06 | 85.4 ± 7.6 | 84.3 ± 7.5 | NS | NS |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 148.4 ± 14.8e | 163.5 ± 14.9 | NS | 106.7 ± 8.1 | 79.2 ± 6.3 | <0.001d | 0.02 |

| Non-HDL C (mg/dl) | 70.6 ± 3.5 | 87.6 ± 4.4 | 0.004d | 65.3 ± 2.0 | 62.3 ± 1.9 | NS | 0.002d |

| Adiponectin (μg/ml) | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | 0.01 | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 11.6 ± 1.2 | <0.001d | <0.001d |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 40.6 ± 3.8 | 46.8 ± 3.9 | 0.001d | 43.8 ± 4.6 | 42.7 ± 4.9 | NS | 0.02 |

| hs-CRP (mg/liter) | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 0.001d | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | NS | NS |

| SBP, morning (mm Hg) | 108.5 ± 3.0 | 112.2 ± 2.1 | NS | 108.2 ± 2.6 | 107.5 ± 2.7 | NS | NS |

| DBP, morning (mm Hg) | 58.1 ± 1.7 | 59.5 ± 1.2 | NS | 58.1 ± 2.0 | 58.7 ± 1.2 | NS | NS |

| SBP, night (mm Hg) | 112.9 ± 2.1 | 116.9 ± 1.9 | NS | 117.5 ± 2.8 | 115.2 ± 2.5 | NS | NS |

| DBP, night (mm Hg) | 58.6 ± 1.6 | 62.6 ± 1.1 | 0.02 | 63.0 ± 1.5 | 61.7 ± 1.5 | NS | 0.03 |

The Δ during the ACTH stimulation test is change in hormone levels from 0–30 min. AA, African-American; C, Caucasian; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NGT, normal glucose tolerance; NS, not significant; SAT, sc adipose tissue; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Paired t test within each treatment group (pre- vs. posttreatment).

Repeated-measures general linear model; P represents the interaction of between-subjects (treatment arm) and within-subjects (time) effects.

χ2 test.

P values that remained significant (P ≤ 0.004) after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Triglycerides at baseline were significantly higher in the drospirenone/EE group (P = 0.02); all other listed measures were similar at baseline between the two study arms.

Effects of treatment on androgen profile, response to the ACTH stimulation test, and clinical characteristics

There were no pretreatment differences in plasma testosterone concentrations or in the incremental response to the ACTH stimulation test (change in hormone levels from 0–30 min) between the two groups. Both treatment modalities resulted in a significant decrease in free testosterone and percent free testosterone and in a significant increase in SHBG, with a more significant effect for drospirenone/EE (Table 1). There were no differences in the response to ACTH stimulation testing between the two groups (Table 1).

In the rosiglitazone arm, pretreatment, three participants had secondary amenorrhea, two of whom did not have any periods throughout the study, and one had one period at month 5. Ten participants in the same arm had oligomenorrhea pretreatment (fewer than six cycles per year); eight of those had regular monthly periods, one had only three periods, and one did not have any periods throughout the study. The remaining four participants in the same arm had irregular menses pretreatment and regular menses during the study.

In the drospirenone/EE arm, pretreatment, one participant had amenorrhea, and she had regular periods during the study. The other participants had either oligomenorrhea (n = 13), irregular periods (n = 3), or monthly periods with intermittent spotting (n = 3) pretreatment, and they all had regular menses during the study. The changes in menstruation compared with baseline were not different between the two treatment arms (P = 0.7).

Effects of treatment on weight and body composition

In both study arms, there were no significant changes in weight, BMI, BMI percentile, waist circumference, fat mass, or percent body fat after 6 months of treatment (Table 1). However, treatment with rosiglitazone was associated with a significant decrease in VAT (Table 1).

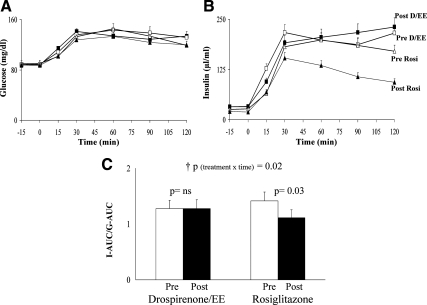

Effects of treatment on glucose tolerance

The changes in glucose tolerance status from baseline to study completion were not statistically different between the two treatment arms (P = 0.4) (Table 1). Neither treatment was associated with significant changes in glucose concentrations during the OGTT (Fig. 2A). However, rosiglitazone treatment was associated with significant reductions in insulin concentrations (Fig. 2B). Accordingly, the ratio of OGTT insulin area under the curve (AUC) to glucose AUC was significantly lower in the rosiglitazone arm (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

A and B, Glucose and insulin responses during the OGTT (drospirenone/EE: □, pretreatment; ■, posttreatment; rosiglitazone: ▵, pretreatment; ▴, posttreatment); C, ratio of insulin AUC to glucose AUC (I-AUC/G-AUC) during the OGTT pre- and posttreatment in the drospirenone/EE and the rosiglitazone groups. p, Paired t test; †p, repeated-measures analysis (treatment × time) interaction, confirmed by intent-to-treat analysis. ns, Not significant.

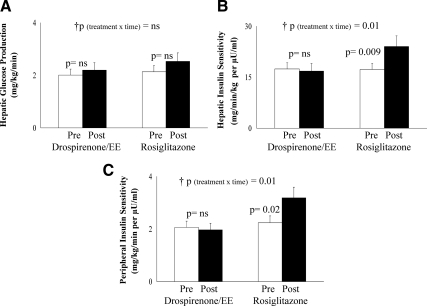

Effects of treatment on insulin sensitivity and secretion

Pre- vs. posttreatment fasting glucose concentrations did not differ with either treatment; however, fasting insulin levels decreased significantly with rosiglitazone (Table 1). Fasting hepatic glucose production did not change with either treatment (Fig. 3A); however, hepatic insulin sensitivity increased significantly in the rosiglitazone group (Fig. 3B). Peripheral insulin sensitivity, expressed per kilogram body weight (Fig. 3C) or per kilogram fat-free mass (data not shown), increased significantly in the rosiglitazone arm with no change in the drospirenone/EE arm. The change in insulin sensitivity negatively correlated with the change in VAT in the pooled groups (r = −0.415; P = 0.02). There were no treatment-associated differences in either first-phase or second-phase insulin secretion or in the disposition index (Fig. 4, A–C).

Fig. 3.

Fasting hepatic glucose production (A), hepatic insulin sensitivity (B), peripheral insulin sensitivity per kilogram body weight (C), pre- and posttreatment in the drospirenone/EE and in the rosiglitazone groups. p, Paired t test; †p, repeated-measures analysis (treatment × time) interaction, confirmed by intent-to-treat analysis. ns, Not significant.

Fig. 4.

First- and second-phase insulin levels during the hyperglycemic clamp (A and B), and the disposition index (C), pre- and posttreatment in the drospirenone/EE and the rosiglitazone arms. p, Paired t test; †p, repeated-measures analysis (treatment × time) interaction, confirmed by intent-to-treat analysis. ns, Not significant.

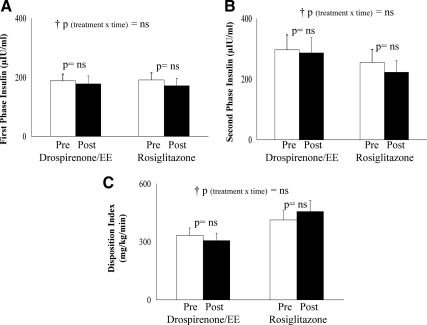

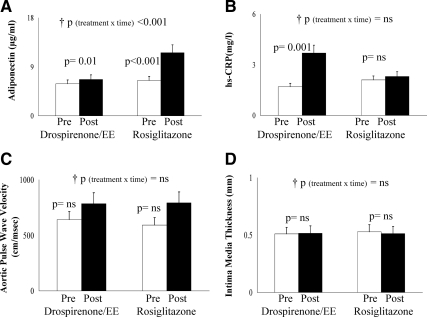

Effects of treatment on cardiovascular risk factors

Treatment with drospirenone/EE was associated with significant increases in total cholesterol, HDL, and non-HDL cholesterol, whereas treatment with rosiglitazone was associated with a significant decline in triglycerides (Table 1). Rosiglitazone was associated with a greater increase in adiponectin levels (Fig. 5A), whereas drospirenone/EE led to elevations in leptin (Table 1) and hs-CRP (Fig. 5B). Posttreatment subjects in the drospirenone/EE arm had significantly higher evening diastolic blood pressure compared with the rosiglitazone arm (Table 1). Neither treatment was associated with significant changes in aortic PWV and IMT (Fig. 5, C and D).

Fig. 5.

Adiponectin (A), hs-CRP (B), aortic PWV (C), and IMT (D), pre- and posttreatment in the drospirenone/EE and the rosiglitazone arms. p, Paired t test; †p, repeated-measures analysis (treatment × time) interaction, confirmed by intent-to-treat analysis for adiponectin, PWV, and IMT. P (treatment × time) = 0.004 by intent-to-treat analysis for hs-CRP. ns, Not significant.

Intent-to-treat analysis

All the above reported interactions P values (i.e. time × treatment) were tested with the intent-to-treat analysis. Significances were similar with the following exceptions (Δ androstenedione, P = 0.03; LDL, P = 0.03; and hs-CRP, P = 0.004, with more significant increase in the drospirenone/EE arm).

Discussion

In this double-blind randomized trial, we compared the effects of 6 months treatment with drospirenone/EE vs. rosiglitazone on the hormonal, metabolic, and cardiovascular risk profiles of overweight/obese adolescents with PCOS. Our data show that 1) both treatments are effective in attenuating hyperandrogenemia and restoring menstrual cycles, although drospirenone/EE is more effective; 2) neither treatment was associated with significant weight gain or increase in percent body fat, although rosiglitazone was associated with significant reductions in VAT; 3) rosiglitazone improved peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity, decreased fasting insulin levels, and insulin AUC during the OGTT, whereas drospirenone/EE did not affect these parameters; 4) rosiglitazone lowered triglyceride concentration, whereas drospirenone/EE increased total cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol concentrations; 5) rosiglitazone treatment improved adiponectin levels, whereas drospirenone/EE resulted in increased levels of leptin and hs-CRP; and lastly, 6) neither treatment affected PWV or IMT.

The improvement in androgen profile and regulation of menses observed with drospirenone/EE is consistent with previous reports (15, 17, 18). Treatment with thiazolidinediones in women with PCOS was reported in some studies to improve androgenic profile (24). However, to our knowledge, there are no reported studies with thiazolidinediones in adolescents. In our study, drospirenone/EE-treated patients had an approximately 7-fold increase in SHBG, which could be attributed to the estrogen component of this OCP, whereas the rosiglitazone-treated patients had a significant but modest increase in SHBG, which is mostly related to the improvement in insulin sensitivity. This discrepancy in SHBG elevation is a possible explanation for the differences in posttreatment free testosterone levels between the two treatment arms. The observed decline in total testosterone with rosiglitazone in the present study (P < 0.04) should be regarded with caution because of the multiple analyses.

Because PCOS is not only a hormonal/reproductive disorder but also a dysmetabolic syndrome with severe insulin resistance, the main outcome measure chosen for this study was insulin sensitivity. The latter improved significantly with rosiglitazone treatment but did not change with drospirenone/EE. Both hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity improved by approximately 40–45% with rosiglitazone, translating to lower fasting and stimulated insulin levels during the OGTT. Studies in adult overweight women with PCOS treated with rosiglitazone for 4 months compared with placebo showed an improvement in insulin sensitivity, measured by the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, despite an increase in BMI (24). Other studies in overweight/obese PCOS women treated with rosiglitazone showed similar improvements using various insulin sensitivity measures (26, 31). Our findings advance the previous observations in adults to demonstrate that rosiglitazone treatment in adolescents with PCOS, besides improving insulin sensitivity, was not associated with significant weight or BMI increase but resulted in favorable decreases in VAT and improvements in adiponectin levels and circulating triglycerides. These observations could be interrelated and explained by the improvement in VAT, an important determinant of insulin sensitivity and metabolic syndrome components in youth (32).

Similar to our findings, a randomized open-label 6-months treatment study of adult women with PCOS with an OCP with antiandrogenic properties did not result in worsening of OGTT-derived insulin sensitivity parameters (18). In this study, similar to ours, weight, BMI, waist circumference, and fat mass did not worsen with OCP (18). A pilot study in adolescent girls with PCOS showed a decrease in insulin AUC after 6 months treatment with a desogestrel-containing OCP with no change in fasting insulin or fasting glucose (15). However, those participants had lower BMI at study completion, and their total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and CRP increased (15). On the other hand, 12 months treatment of adolescents with PCOS with two different forms of OCPs led to deterioration in fasting- and OGTT-derived insulin sensitivity parameters, despite maintenance of BMI and waist to hip ratio (17). The longer duration of treatment and the different forms of OCPs may partly explain the discrepancy between our findings and the latter study. Nevertheless, the concern remains for the potential of deteriorating insulin sensitivity with the prolonged use of OCPs in overweight/obese girls. Moreover, the observed contrast between adult studies and the present study, with respect to weight reduction and reversal of impaired glucose tolerance with rosiglitazone in adults, could stem from differences in the natural history of obesity, insulin resistance, and β-cell dysfunction, which could be more aggressive in youth, potentially necessitating longer treatments. Additional data need to be generated to address such differences.

The increase in total cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol despite maintenance of body weight and composition is concerning. This effect, however, may be offset by a significant increase in HDL, which has been reported in several studies with different OCPs (15, 16, 18). The estrogen component of the OCP is believed to play an important role in this increase (33), possibly through its effect on the hepatic lipase enzyme (34). The increase in total cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides has been reported in some studies of adolescents treated with another OCP with an antiandrogenic component (16) but not in other studies (18). Differences in duration of treatment and study populations may explain this variation.

Another important finding is the increase in hs-CRP, a marker of inflammation linked to increased risk of coronary events independent of other cardiovascular disease risk factors (35), with drospirenone/EE treatment. With respect to IMT and PWV, early markers of atherosclerosis, neither treatment was associated with significant changes in the present study. Whether or not this is related to the relatively short duration of treatment remains to be determined.

One limitation to our study is the potential unblinding due to the rapid regulation of withdrawal bleeding with drospirenone/EE vs. rosiglitazone, which may have influenced the dropout rates. Another limitation is the short duration of treatment in contrast to clinical practice where treatment may be required for several years. Studies that address the effects of longer duration of treatment are needed. The recent U.S. Food and Drug Administration restrictions on rosiglitazone, based on metaanalyses showing increased risk of cardiovascular disease events in adults with type 2 diabetes (36), may impose barriers to its use in adolescents with PCOS. Studies with other insulin sensitizers may be warranted in adolescents with PCOS. It remains questionable whether different doses of rosiglitazone would result in similar effects (26) or other thiazolidinediones may differ in their effect. Our findings in obese/overweight adolescents may not apply to normal-weight adolescents with PCOS. Lastly, the secondary outcome results should be interpreted with caution due to the multiple comparisons; to account for this limitation, we applied the Bonferroni correction to the secondary outcomes as detailed in Table 1.

In conclusion, treatment with either drospirenone/EE or rosiglitazone is effective in improving hyperandrogenemia and restoring menstrual cycles, with the former being more effective. On the other hand, rosiglitazone is superior in improving insulin sensitivity, decreasing visceral adiposity, improving triglycerides and adiponectin levels, whereas drospirenone/EE showed a negative impact on hs-CRP and lipid profile. These factors are important considerations when treating obese adolescent with PCOS, who are already at heightened risk of metabolic disturbances. Ultimately, the choice of a therapeutic modality should be individually tailored to address the priorities for each patient. Considerations include treatment for hirsutism and acne, reproduction or contraception, weight gain, and metabolic disturbances, within the context of genetic and familial risk for cardiometabolic disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the assistance of Nancy Guerra, CRNP; Marcie De Leo, CRNP; Olga Pizov, CRNP; and Julie Byrne, CRNP; the laboratory expertise of Theresa Stauffer and Katie McDowell; and the assistance of the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center nurses and staff. We thank Patricia R. Houck, MSH, for statistical assistance. Most important, we are thankful to the study participants and their parents.

Disclosure summary: H.T., J.W.-U., K.S.-T., and S.A. have nothing to disclose. S.L. had purchased stocks in Glaxo Smith Kline before joining our research team (less than $10,000). We became aware of this at the time of manuscript submission.

Clinical trial registration number: NCT00640224.

This research was supported by grants from the Endocrine Fellows Foundation (to J.W.-U.), T32 DK063686 (to principal investigator S.A. and trainee J.W.-U.), K24-HD01357 (to S.A.), Richard L. Day Endowed Chair (to S.A. and H.T.), M01-RR00084, and UL1 RR024153 (Clinical and Translational Science Award).

Footnotes

- AUC

- Area under the curve

- BMI

- body mass index

- DHEAS

- dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- EE

- ethinyl estradiol

- LDL

- low-density lipoprotein

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- hs-CRP

- high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- IMT

- intima media thickness

- OCP

- oral contraceptive

- OGTT

- oral glucose tolerance test

- 17-OHPreg

- 17-hydroxypregnenolone

- 17-OHProg

- 17-hydroxyprogesterone

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- PWV

- pulse wave velocity

- SHBG

- sex hormone-binding globulin

- TZD

- thiazolidinedione

- VAT

- visceral adipose tissue.

References

- 1. Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Kouli CR, Bergiele AT, Filandra FA, Tsianateli TC, Spina GG, Zapanti ED, Bartzis MI. 1999. A survey of the polycystic ovary syndrome in the Greek island of Lesbos: hormonal and metabolic profile. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:4006–4011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asunción M, Calvo RM, San Millán JL, Sancho J, Avila S, Escobar-Morreale HF. 2000. A prospective study of the prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected Caucasian women from Spain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:2434–2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. 2004. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2745–2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azziz R, Marin C, Hoq L, Badamgarav E, Song P. 2005. Health care-related economic burden of the polycystic ovary syndrome during the reproductive life span. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:4650–4658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, Janssen OE, Legro RS, Norman RJ, Taylor AE, Witchel SF. 2006. Positions statement: criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an Androgen Excess Society guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4237–4245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ehrmann DA. 2005. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 352:1223–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coviello AD, Legro RS, Dunaif A. 2006. Adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome have an increased risk of the metabolic syndrome associated with increasing androgen levels independent of obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:492–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lewy VD, Danadian K, Witchel SF, Arslanian S. 2001. Early metabolic abnormalities in adolescent girls with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Pediatr 138:38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palmert MR, Gordon CM, Kartashov AI, Legro RS, Emans SJ, Dunaif A. 2002. Screening for abnormal glucose tolerance in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1017–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tfayli H, Arslanian S. 2008. Menstrual health and the metabolic syndrome in adolescents. Ann NY Acad Sci 1135:85–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glueck CJ, Morrison JA, Friedman LA, Goldenberg N, Stroop DM, Wang P. 2006. Obesity, free testosterone, and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome and regularly cycling adolescents. Metabolism 55:508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arslanian SA, Lewy VD, Danadian K. 2001. Glucose intolerance in obese adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome: roles of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction and risk of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:66–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saad R, Gungor N, Arslanian S. 2005. Progression from normal glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes in a young girl: longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion assessed by the clamp technique and surrogate estimates. Pediatr Diabetes 6:95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warren-Ulanch J, Arslanian S. 2006. Treatment of PCOS in adolescence. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 20:311–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoeger K, Davidson K, Kochman L, Cherry T, Kopin L, Guzick DS. 2008. The impact of metformin, oral contraceptives, and lifestyle modification on polycystic ovary syndrome in obese adolescent women in two randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4299–4306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mastorakos G, Koliopoulos C, Creatsas G. 2002. Androgen and lipid profiles in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome who were treated with two forms of combined oral contraceptives. Fertil Steril 77:919–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mastorakos G, Koliopoulos C, Deligeoroglou E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Creatsas G. 2006. Effects of two forms of combined oral contraceptives on carbohydrate metabolism in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 85:420–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luque-Ramírez M, Alvarez-Blasco F, Botella-Carretero JI, Martínez-Bermejo E, Lasunción MA, Escobar-Morreale HF. 2007. Comparison of ethinyl-estradiol plus cyproterone acetate versus metformin effects on classic metabolic cardiovascular risk factors in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2453–2461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arslanian SA, Lewy V, Danadian K, Saad R. 2002. Metformin therapy in obese adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome and impaired glucose tolerance: amelioration of exaggerated adrenal response to adrenocorticotropin with reduction of insulinemia/insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1555–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perry CG, Petrie JR. 2002. Insulin-sensitising agents: beyond thiazolidinediones. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 7:165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quinn CE, Hamilton PK, Lockhart CJ, McVeigh GE. 2008. Thiazolidinediones: effects on insulin resistance and the cardiovascular system. Br J Pharmacol 153:636–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dunaif A, Scott D, Finegood D, Quintana B, Whitcomb R. 1996. The insulin-sensitizing agent troglitazone improves metabolic and reproductive abnormalities in the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:3299–3306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lemay A, Dodin S, Turcot L, Déchêne F, Forest JC. 2006. Rosiglitazone and ethinyl estradiol/cyproterone acetate as single and combined treatment of overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome and insulin resistance. Hum Reprod 21:121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rautio K, Tapanainen JS, Ruokonen A, Morin-Papunen LC. 2006. Endocrine and metabolic effects of rosiglitazone in overweight women with PCOS: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Hum Reprod 21:1400–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aroda VR, Ciaraldi TP, Burke P, Mudaliar S, Clopton P, Phillips S, Chang RJ, Henry RR. 2009. Metabolic and hormonal changes induced by pioglitazone in polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:469–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cataldo NA, Abbasi F, McLaughlin TL, Basina M, Fechner PY, Giudice LC, Reaven GM. 2006. Metabolic and ovarian effects of rosiglitazone treatment for 12 weeks in insulin-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 21:109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zawadzki JK, DA 1992. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rationale approach. Boston, MA: Blackwell Scientific Publications [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gungor N, Bacha F, Saad R, Janosky J, Arslanian S. 2005. Youth type 2 diabetes: insulin resistance, β-cell failure, or both? Diabetes Care 28:638–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bacha F, Saad R, Gungor N, Arslanian SA. 2004. Adiponectin in youth: relationship to visceral adiposity, insulin sensitivity, and β-cell function. Diabetes Care 27:547–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wildman RP, Mackey RH, Bostom A, Thompson T, Sutton-Tyrrell K. 2003. Measures of obesity are associated with vascular stiffness in young and older adults. Hypertension 42:468–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ghazeeri G, Kutteh WH, Bryer-Ash M, Haas D, Ke RW. 2003. Effect of rosiglitazone on spontaneous and clomiphene citrate-induced ovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 79:562–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee S, Gungor N, Bacha F, Arslanian S. 2007. Insulin resistance: link to the components of the metabolic syndrome and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction in youth. Diabetes Care 30:2091–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Crook D, Seed M. 1990. Endocrine control of plasma lipoprotein metabolism: effects of gonadal steroids. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 4:851–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tikkanen MJ, Nikkilä EA. 1987. Regulation of hepatic lipase and serum lipoproteins by sex steroids. Am Heart J 113:562–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Corrado E, Rizzo M, Coppola G, Fattouch K, Novo G, Marturana I, Ferrara F, Novo S. 2010. An update on the role of markers of inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb 17:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nissen SE, Wolski K. 2007. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 356:2457–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]