Abstract

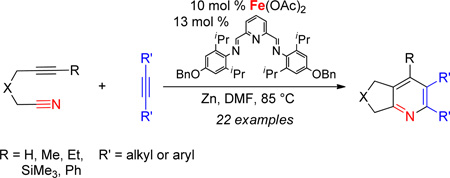

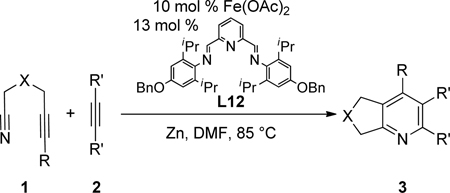

The combination of Fe(OAc)2 and an electron-donating, sterically-hindered pyridyl bisimine ligand catalyzes the cycloaddition of alkynenitriles and alkynes. A variety of substituted pyridines were obtained in good yields.

The abundance and affordability of iron makes it an attractive catalyst source. However, until recently, the number of catalytic processes (other than oxidation1 and polymerization2) iron complexes could facilitate has been low. Over the past decade, the quantity of efficient iron-based catalyst systems has significantly risen.3 For example, effective Fe-catalyzed cross-coupling chemistry4 and cycloaddition chemistry5 has emerged. To date, Fe-catalyzed cycloadditions have been mostly limited to the formation of carbocycles. In 1872, Sir Ramsay demonstrated that the addition acetylene and hydrocyanic acid through a red-hot iron pipe led to the formation of pyridine.6

Despite this very early observation, an effective and general Fe-based catalyst that mediates cycloadditions to form pyridines is still absent.7 Herein, we describe a general iron catalyst that couples alkynenitriles and alkynes to form pyridines.8

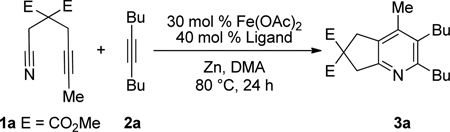

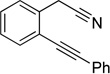

Given the efficacy of Fe-catalyzed cycloadditions to generate carbocyclic structures, we surmised that the inability to prepare pyridines was due to limited reactivity of the nitrile (i.e., for either oxidative coupling or insertion). Thus, alkynenitrile 1a, which tethers the nitrile to the alkyne, was chosen as a model substrate. Alkynenitrile 1a and butyne 2a were subjected to 30 mol % Fe(OAc)2,9 40 mol % ligand, and Zn in DMA at 80 °C (eq 1).

|

(1) |

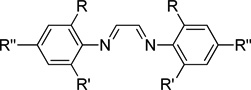

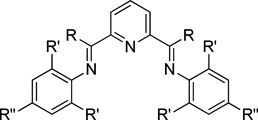

A variety of amines, phosphines, and NHCs (NHC = N-heterocyclic carbene) were evaluated as potential ligand arrays. Neither the use of phosphines or NHCs led to any detectable cycloaddition product. Imino-based ligands have successfully been employed in various Fe-mediated reactions.10,11 As such, bisimines and pyridyl bisimines were also evaluated (Table 1). Although consumption of the alkynenitrile was observed, low or no pyridine was formed in most cases (entries 1–5). An appreciable amount of the desired pyridine product was formed when imine L6 was used as the ligand (entry 6). Unfortunately, all attempts to optimize this reaction failed; yields above 50% were never obtained.

Table 1.

Ligand screen with various bisimine ligandsa

| entry | ligand | coversionb | yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| 1 | R = R' = R" = Me, L1 | 100 | 13 |

| 2 | R = Me, R' = R" = H, L2 | 58 | 0 |

| 3 | R = R'= tBu, R" = H, L3 | 40 | 0 |

| 4 | R = tBu, R' = R" = H, L4 | 36 | 0 |

| 5 | R = Et, R" = R" = H, L5 | 89 | 17 |

| 6 | R = R' = iPr, R" = H, L6 | 100 | 47 |

|

|||

| 7 | R = Me, R' = R" = Me, L7 | 43 | 0 |

| 8 | R = Me, R' = iPr, R" = H, L8 | 63 | 2 |

| 9 | R = H, R' = R" = Me, L9 | 100 | 84 |

| 10 | R = H, R' = iPr, R" = H, L10 | 42 | 0 |

| 11 | R = H, R' = Me, R" = OBn, L11 | 100 | 62c |

Reaction conditions: 30 mol % Fe(OAc)2, 40 mol % Ligand, 40 mol % Zn, 0.1 M DMA, 80 °C, 24 h.

Determined by gas chromatography with naphthalene as internal standard.

Reaction conditions: 20 mol % Fe(OAc)2, 27 mol % Ligand, 22 mol % Zn, 0.1 M DMA, 80 °C.

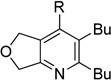

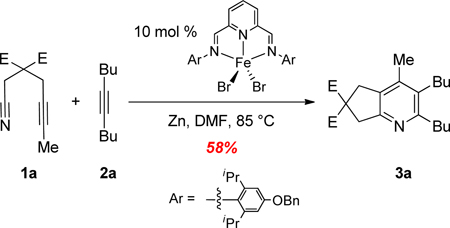

We then turned our attention to pyridyl bisimines (entries 7–12). Reactions run with pyridyl bisimines derived from the corresponding pyridyl bisketones did not afford any pyridine cycloaddition product (entries 7–8). However, reactions run with pyridyl bisimines derived from the corresponding pyridyl bisaldehydes gave promising results. For example, quantitative conversion of the alkynenitrile was observed with L9 (entry 9). Importantly, the pyridine product was observed in 84% GC yield. An increase in the steric bulk of the ligand seemed to have a dramatic deleterious effect on the reaction (entry 10). Specifically, reactions run with L10 gave hardly any conversion and no desired pyridine product. Amazingly, the addition of an electron-donating group (i.e., -OBn) to the para position of the aryl rings had a profound effect on product formation (entries 11–12). When L11 was used as the ligand, the desired pyridine product was formed in 62% yield despite employing a lower catalyst loading of 20 mol % (entry 11). Even more surprisingly, in contrast to the trend observed for neutral ligands, an increase in steric hinderance led to an increase in yield (entries 9–10 vs. entries 11–12, respectively). That is, reactions run with L12 provided the pyridine product in 95%, again while employing a lower catalyst loading (entry 12). Importantly, individual control reactions run without Fe(OAc)2, ligand, or Zn resulted in no pyridine product formation. Further optimization ultimately led to the following reaction conditions: 10 mol % Fe(OAc)2, 13 mol % bisimine L12, 0.4 M alkynenitrile, and 0.4 M alkyne in DMF, rather than DMA, at 85 °C (eq 2).

|

(2) |

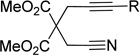

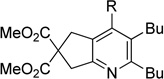

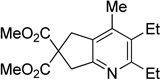

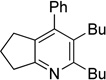

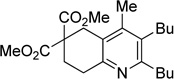

The Fe(OAc)2/L12-catalyzed cycloaddition of alkynenitriles and alkynes is a general reaction as a variety of alkynenitriles and alkynes can be used as substrates (Table 2). The reaction between alkynenitriles 1a and 1b with dec-5-yne (2a) afforded good isolated yields of the pyridine products (entries 1–2). Similarly, the reaction of phenyl-substituted alkynenitrile 1c also afforded the corresponding pyridine in good yield (entry 3).

Table 2.

Fe(OAc)2/L12-catalyzed cycloaddition of cyanoalkynes and symmetrical alkynesa

| entry | cyanoalkyne (1) | alkyne (2) | time(h) | product (% yield)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

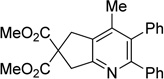

|

|

|||

| 1 | R = Me, 1a | 2a | 2h | 3a, 70 |

| 2 | R = Et, 1b | 2a | 26h | 3b, 86 |

| 3 | R = Ph, 1c | 2a | 5h | 3c, 75 |

| 4 | R = H, 1d | 2a | 26h | 3d, 30 |

| 5 | R = SiMe3, 1e | 2a | 6h | 3e, 57 |

|

||||

| 6 | 1a | 2b | 6h | 3f, 71 |

|

||||

| 7 | 1a | 2c | 5h | 3g, 54c |

|

|

|||

| 8 | R = Et, 1f | 2a | 4h | 3h, 41 |

| 9 | R = Ph, 1g | 2a | 4h, | 3i, 45 |

|

|

|||

| 10 | 1h | 2a | 4h | 3j, 41 |

|

|

|||

| 11 | 1i | 2a | 4h | 3k, 65 |

|

|

|||

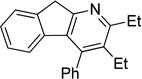

| 12 | 1j | 2b | 4h | 3l, 64 |

|

|

|||

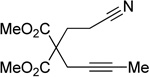

| 13 | 1k | 2a | 24h | 3m, 40d |

Reaction Conditions: 0.4 M 1, 0.4 M 2, 10 mol % Fe(OAc)2, 13 mol % L12, 20 mol % Zn, DMF, 85 °C.

Average of at least two reaction runs.

2 equiv of alkyne.

Reaction Conditions: 0.4 M 1, 0.4 M 2, 20 mol % Fe(OAc)2, 26 mol % L12, 40 mol % Zn, DMF, 85 °C.

Although the cycloaddition of terminal alkynenitrile 1d resulted in low yield (entry 4),5d a reasonable yield was obtained when TMS-substituted alkynenitrile 1e was employed (entry 5). Not surprisingly, 3-hexyne (2b) is an equally effective alkyne substrate (entry 6). Due to competing cyclotrimerization of the alkyne, the cycloaddition of diphenylacetylene 2c and alkynenitrile 1a requires 2 equivalents of 2c to afford the pyridine product in appreciable yield (entry 7). Alkynenitriles containing an either oxygen or a nitrogen backbone (1f, g, and 1h) also react with decyne 2a to afford the pyridine product, albeit in moderate yields (entries 8–10). In contrast, alkynenitrile 1h, which possesses an all-carbon backbone, reacted with decyne 2a and afforded better yields of the pyridine cycloaddition product (entry 11). A tricyclic indenylpyridine was prepared in good yield from the coupling of 1j and 2b (entry 12). In addition, the reaction of alkynenitrile 1k, which possesses a 6-carbon chain that tethers an alkyne to the cyano group, and 2a affords bicycle 3k, albeit in lower yields than the corresponding alkynenitrile which possesses a 5-carbon tether (entry 13 vs. entry 1, respectively).

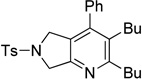

Unsymmetrical alkynes also react in the cycloaddition reaction (eq 3, Table 3). Methyl phenyl acetylene 2d and alkynenitrile 1a afford the pyridine product with 1.2:1 ratio of regioisomers (entry 1). Cycloaddition of an alkyne possessing an electron withdrawing group (p-CF3) (entry 3) affords a higher ratio of the major regioisomer where the phenyl ring is distal from the pyridine nitrogen as compared to an alkyne possessing an electron donating group (entry 2). The reaction of alkynenitrile 1a and alkyne 2g, possessing a pyridyl substituent, also affords a mixture of pyridine products where the aryl ring is distal to the pyridine nitrogen in the major regioisomer (entry 4). A relatively equal mixture of regioisomers were obtained in the reactions of aryl-alkyl alkynes 2h and 2i (entries 5–6). As expected, the cycloaddition of unsymmetrical alkyl-alkyl alkyne 2j and alkynenitrile 1a afforded a 1:1 ratio of the pyridine products in a good yield (entry 7). Pyridine product was obtained as a single regioisomer in the reaction of a sterically hindered alkyne (i.e., methyl-tBu-acetylene 2k, entry 8). Interestingly, the tBu-group is proximal to the nitrogen of the pyridine (entry 8).

|

(3) |

Table 3.

Cycloaddition of 1a and unsymmetrical alkynesa

| entry | alkyne (2) | reaction time | product % yield (3:3')b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ar = Ph, R = Me 2d | 6h | 3n, 69 (1.2:1) |

| 2 | Ar = p-OMeC6H4, R = Me, 2e | 6h | 3o, 39 (3:2) |

| 3 | Ar = p-CF3C6H4, R = Me, 2f | 6h | 3p, 39 (4:1) |

| 4 | Ar = Py, R = Me, 2g | 16h | 3q, 56 (7:3) |

| 5 | Ar = Ph, R = Bu, 2h | 5h | 3r, 53 (2:3) |

| 6 | Ar = Ph, R = −(CH2)2NTsBoc 2i | 5h | 3s, 44 (3:2) |

| 7 | R = Me, R' = Bu, 2j | 24h | 3t, 62 (1:1) |

| 8 | R = Me, R' = tBu,2k | 6h | 3u, 26 (0:1) |

Reaction Conditions: 0.4 M 1, 0.4 M 2, 10 mol % Fe(OAc)2, 13 mol % L12, 20 mol % Zn, DMF, 85 °C.

Average of at least two reaction runs.

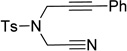

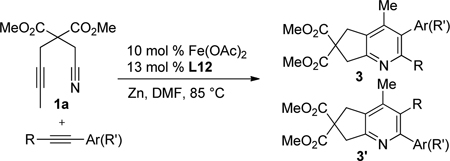

The catalytic system is also effective in the all-intramolecular cycloaddition. Specifcally, addition of 20 mol % Fe(OAc)2 and 32 mol % L12 to substrate 1l afforded tricyclic product 3v in 74% isolated yield (eq 4).

|

(4) |

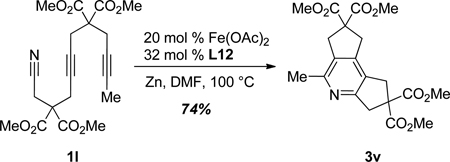

Efforts to isolate an (L12)Fe(OAc)n complex12 proved unsuccessful. However, the analogous (L12)FeBr2 2a,b complex was prepared and used as a catalyst for the cycloaddition of 1a and 2a (eq 5). Importantly, this well-defined Fe complex did catalyze the coupling and afforded pyridine 3a in 58% isolated yield. For comparison, reactions run with 10 mol % FeBr2, in lieu of Fe(OAc)2, provided pyridine 3a in 54% (GC yield).13

|

(5) |

In conclusion we have developed a methodology to prepare pyridines from alkynenitriles and alkynes by employing catalytic amounts of iron acetate and a pyridyl bisimine ligand. Efforts to understand the reactivity patterns of different pyridyl bisimine ligands in the cycloaddition reaction are currently underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the NSF and NIGMS (5RO1GM076125) for support of this research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information All experimental procedures for new substrates and products as well as copies of NMR spectra are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Pleitker OB, editor. Iron Catalysis in Organic Chemistry: Reactions and Applications. Wiley-VCH Weinheim; 2008. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen MS. Science. 2010;327:566. doi: 10.1126/science.1183602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen MS, White MC. Science. 2007;318:783. doi: 10.1126/science.1148597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen K, Que L., Jr Chem. Commun. 1999:1375. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kim C, Chen K, Kim J, Que J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5964. [Google Scholar]; (e) Okuno T, Ito S, Ohba S, Nishida Y. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1997:3547. [Google Scholar]; (f) Groves JT, Viski P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:8537. [Google Scholar]; (g) Khenkin AM, Shilov AE. New J. Chem. 1989;13:659. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Ouchi M, Terashima T, Mitsuo S. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:4963. doi: 10.1021/cr900234b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Louie J, Grubbs RH. Chem. Commun. 2000:1479. [Google Scholar]; (c) Britovsek GJP, Bruce M, Gibson VC, Kimberley BS, Maddox PJ, Mastroianni S, McTavish SJ, Redshaw C, Solan GA, Strömberg S, White AJP, Williams DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:8728. [Google Scholar]; (d) Small BL, Brookhart M, Bennett AMA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4049. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Bolm C, Legros J, Le Paih J, Zani L. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:6217. doi: 10.1021/cr040664h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Correa A, Garcia MO, Bolm C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:1108. doi: 10.1039/b801794h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakamura E, Yoshikai N. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:6010. doi: 10.1021/jo100693m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Fürstner A, Martin R. Chem. Lett. 2005;34:624. [Google Scholar]; (b) Czaplik WM, Mayer M, Cvengroš J, von Wangelin AJ. ChemSusChem. 2009;2:396. doi: 10.1002/cssc.200900055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sherry BD, Fürstner A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1500. doi: 10.1021/ar800039x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fürstner A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:1364. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Fürstner A, Majima K, Martin R, Krause H, Kattnig E, Goddard R, Lehmann Christian W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1992. doi: 10.1021/ja0777180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Breschi C, Piparo L, Pertici P, Maria Caporusso A, Vitulli G. J. Organomet. Chem. 2000;607:57. [Google Scholar]; (c) Saino N, Kogure D, Kase K, Okamoto SN, Kogure D, Kase K, Okamoto S. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006;691:3129. [Google Scholar]; (d) Gonzalez-Arellano C, Balu AM, Luque R, MacQuarrie DJ. Green Chemistry. 2010;12:1995. [Google Scholar]; (e) Saino N, Kogure D, Okamoto S. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3065. doi: 10.1021/ol051048q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Ramsay W. Philos. Mag. 1876;2:269. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ramsay W. Philos. Mag. 1877;4:241. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Knoch F, Kremer F, Schmidt U, Zenneck U, Le Floch P, Mathey F. Organometallics. 1996;15:2713. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ferré K, Toupet L, Guerchais V. Organometallics. 2002;21:2578. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Varela JA, Saá C. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:3787. doi: 10.1021/cr030677f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Varela JA, Castedo L, Saá C. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:8585–8598. doi: 10.1021/jo035050b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamamoto Y, Kinpara K, Saigoku T, Takagishi H, Okuda S, Nishiyama H, Itoh KJ. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:605. doi: 10.1021/ja045694g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) McCorwick MM, Duong H, Zuo G, Louie J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5030. doi: 10.1021/ja0508931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yamamoto Y, Kinpara K, Ogawa R, Nishiyama H, Itoh K. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:5618. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wada A, Noguchi K, Hirano M, Tanaka K. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1295. doi: 10.1021/ol070129e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Varela JA, Saá C. Synlett. 2008:2571. [Google Scholar]; (h) Garcia P, Moulin S, Miclo Y, Leboeuf D, Gandon V, Aubert C, Malacria M. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:2129. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iron acetate (99.995 % purity) was used. Buchwald SL, Bolm C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5586. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902237.

- 10.(a) Bart SC, Lobkovsky E, Chirik PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13794. doi: 10.1021/ja046753t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sylvester KT, Chirik PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8772. doi: 10.1021/ja902478p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Moreau Bt, Wu JY, Ritter T. Org. Lett. 2009;11:337. doi: 10.1021/ol802524r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wu JY, Moreau BT, Ritter T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12915. doi: 10.1021/ja9048493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Gibson VC, Redshaw C, Solan GA. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:1745. doi: 10.1021/cr068437y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fernández I, Trovitch RJ, Lobkovsky E, Chirik P. Organometallics. 2008;27:109. [Google Scholar]; (c) Trovitch RJ, Lobkovsky E, Chirik PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11631. doi: 10.1021/ja803296f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Fe(OAc)2 was only partially souble in most polar solvents.

- 13.Reaction conditions: 0.4M 1a, 0.4M 2a, 10 mol % FeBr2, 13 mol % L12, 20 mol % Zn, DMF, 85 °C.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.