SUMMARY

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory multisystem disorder of unknown cause. Approximately 5-7% of patients manifest symptoms of central nervous system involvement, or neurosarcoidosis. Cranial neuropathy usually entails facial nerve palsy and optic neuritis. Sudden hearing loss has been reported in fewer than 20 cases. Herewith, two new cases of sudden hearing loss due to probable neurosarcoidosis are reported, each having a quite different clinical course. In one case, unilateral sudden hearing loss and facial palsy were the presenting symptoms of systemic sarcoidosis, while in the second, unilateral sudden deafness occurred despite ongoing immunosuppressive treatment for systemic sarcoidosis.

KEY WORDS: Sudden hearing loss, Sarcoidosis, Neurosarcoidosis, Auditory brainstem response, Magnetic resonance imaging

RIASSUNTO

La sarcoidosi è una malattia infiammatoria idiopatica multisistemica. Le manifestazioni cliniche di un interessamento del sistema nervoso centrale – neurosarcoidosi – si rilevano in circa il 5-7% dei pazienti. Il nervo facciale e il nervo ottico sono i nervi cranici più comunemente affetti. L'ipoacusia improvvisa è stata riportata in meno di 20 casi. Il presente lavoro riporta due nuovi casi di ipoacusia improvvisa dovuta a probabile neurosarcoidosi dal decorso clinico differente. L'ipoacusia improvvisa e la paralisi del nervo facciale monolaterale sono stati i primi segni di una sarcoidosi sistemica nel primo caso, mentre nel secondo l'ipoacusia improvvisa monolaterale si è verificata nonostante il trattamento immunosoppressivo in corso.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory multi-system disorder of unknown cause. Approximately 5-7% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis manifest symptoms of central nervous system (CNS) involvement, so-called neurosarcoidosis (NS) 1 2, while imaging studies can detect neurological disease in 10% of all patients with sarcoidosis 3. However, prospective studies reveal subclinical neurological involvement of the CNS evidence in up to 26% of patients affected by sarcoidosis 4. The most prevalent symptom of NS in up to 80% of cases, is a cranial neuropathy, with the facial and optic nerve being most affected 1 2 5. Eighth nerve involvement is found in 1-7% of neurosarcoidosis patients 1 2 5-7. The histopathological correlation of audiovestibular dysfunction in neurosarcoidosis was reported by Babin et al. 8, in 1984, in autopsy findings from a deaf patient with NS. The Authors found generalized cranial nerve neuropathy with perivascular lymphocytic and granulomatous inflammation which were particularly striking in acoustic, vestibular and facial nerves within the internal auditory meatus. These processes were associated with diffuse cochlear destruction with the organ of Corti almost completely degenerated. Because of the extent and degree of cochlear destruction without significant infiltration or inflammation within the cochleae, the Authors concluded that audiovestibular impairment in NS is likely due to vascular occlusion and ischemia 8.

Hearing loss, in approximately 90% of reported cases, is characterised by sudden or rapidly progressive onset and in more than 90% of patients, vestibular symptoms with abnormal vestibular functioning tests have been reported. In almost 50% of the cases at least partial hearing recovery has been achieved after high-dose systemic steroid administration, while balance disorders recover either spontaneously or after treatment 8.

Oral corticosteroids are the cornerstone of treatment of NS, although relapse or deterioration have been reported, after a good initial response, upon dose reduction 5-7.

Despite the fact that cranial neuropathy affects up to 80% of patients with NS, detailed descriptions of sudden hearing loss, possibly accompanying symptoms and course have been reported in fewer than 20 cases 9-13. Herewith, two new cases of sudden hearing loss showing a quite different clinical evolution are reported.

Case 1

A 29-year-old male from Senegal was hospitalized at the Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) Clinic of Treviso General Hospital, in December 2004, with left facial nerve paralysis and sudden left hearing loss. He was otherwise healthy. Pure-tone audiometry was performed upon admission and revealed profound sensorineural hearing loss, in the left ear, and mild, in the right (Fig. 1a). The patient was treated with systemic prednisone (1 mg/kg per day for 10 days) and pentoxifylline (400 mg OS t.i.d. for 3 weeks). A slight hearing improvement was recorded two weeks later in both ears (Fig. 1b). However, after corticosteroid suspension in January 2005, the patient was referred to the Audiology and Phoniatrics Service because of sudden right hearing loss. A further pure-tone audiometry was performed revealing only residual hearing (125-1000 Hz) in the right ear and severe hearing loss in the left (Fig. 1c). Distortion products otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) were absent bilaterally. Auditory brainstem response (ABR) was absent in the right ear. Despite severe hearing impairment in the left ear, wave V was identified with absolute latency 5.87 ms, but showing poor morphology and repeatability (Fig. 2a). Two months later ABR was grossly abnormal in both ears (Fig. 2b).

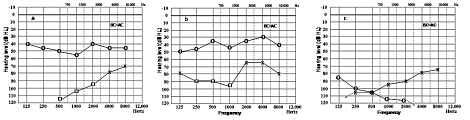

Fig. 1a-c.

Pure tone audiometry performed at admission, December 2004 (a), after 10 days of treatment with Prednisone 1 mg/kg/day, January 2005 (b), and a few days after suspension of prednisone and pentoxyfilline (c). (BC = AC: Bone Conduction = Air Conduction. x: left air conduction threshold; o: right air conduction threshold).

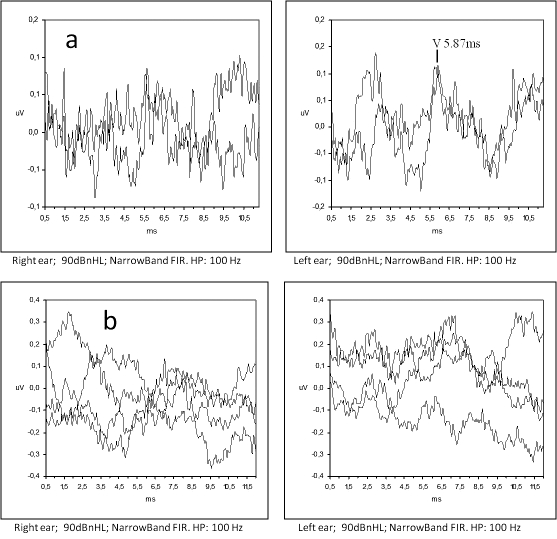

Fig. 2a-b.

(a) Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) performed in January 2005, a few days after suspension of prednisone; the corresponding hearing threshold is reported in Fig. 1c. (b) ABR recordings performed two months later showing highly desynchronized response.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was normal. Due to conjunctival hyperaemia, the patient underwent ophthalmologic evaluation that revealed right anterior uveitis.

Routine chest X-ray showed multiple small pulmonary cavities (< 1 cm) within the apical segment of the left pulmonary lobe. Tuberculosis was excluded by means of negative Mantoux cutaneous reaction and absence of Koch bacilli in the broncho-alveolar lavage culture. Analysis of fluid and cells of broncho-alveolar lavage revealed an increased CD4/CD8 lymphocyte ratio (31) and alveolar macrophages. Multiple trans-bronchial biopsies from the superior pulmonary lobe showed non-specific inflammatory infiltration. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), at 98 U /l, exceeded normal values (NV: 8-52 U/l).

Liver enzymes, alanine amino-transferase (ALT), aspartate amino-transferase (AST) and glutamyl-transpeptidase (GGT) levels were increased. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple lymphadenopathy at the hepatic hilus, and cholelithiasis. Percutaneous hepatic biopsy showed non-caseating and giant-cell granulomas leading, one month after the first symptoms, to the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis with pulmonary, hepatic, ocular and possible CNS involvement. Systemic high dose prednisone treatment was administered for 6 months and then tapered to a maintenance dosage of 7.5 mg/day.

Despite treatment, the patient's hearing evolved to profound deafness within 2 months. Hearing aids were prescribed with very little benefit, while cochlear implant application was refused by the patient. Two years later, he showed no clinical signs of a relapse of systemic sarcoidosis.

Case 2

A 44-year-old male from Sri Lanka was referred to the Audiology and Phoniatrics Service, in April 2009, for ABR recording for sudden right hearing loss. A detailed case history was collected. The patient reported that onset of sudden right hearing loss, was preceded by diplopia and unsteadiness over the previous weeks. He had suffered, since 1996, from diabetes mellitus type II and systemic sarcoidosis that was diagnosed in 2007. Since then he had been receiving prednisone (7.5 mg/day), hydroxychloroquine, alendronic acid, colecalcipherol and ursodesoxycholic acid and insulin substituting previous oral antidiabetics. No other systemic diseases were reported. Pure tone audiometry revealed normal hearing in the left ear and mild sensorineural hearing loss in the right (Fig. 3a). Acoustic reflexes were obtained bilaterally for ipsi-lateral and contra-lateral stimulation. ABR showed normal morphology and latencies, suggesting that the hearing impairment was of cochlear origin (Fig. 3b). Gadolinium-enhanced cerebral MRI was normal. Serum ACE levels were within the normal range. Because of the negativity of cerebral MRI, the absence of unequivocal signs suggesting a relapse of sarcoidosis, the complex therapeutic regime and diabetes mellitus, the corticosteroid dosage was not modified.

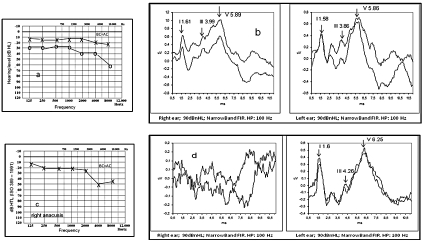

Fig. 3a-d.

Pure tone audiometry (a) and (b) first ABR performed April 2009; pure tone audiometry (c) showing right anacusis and mild left hearing loss mainly affecting high frequencies and ABR (d), both performed November 2009. NB. Absence of response in right ear and preserved morphology in left with prolonged inter-peak intervals mostly due to I-III interval (2.66 msec; nv < 2.4 msec) suggesting retro-cochlear involvement. (BC = AC: Bone Conduction = Air Conduction. x; left air conduction threshold).

The patient was referred again to our Service 6 months later, in November 2009, because of sudden right hearing loss, hypoesthesia of the right auricle and frontal headaches. The patient denied changes in hearing acuity in the left ear. Physical examination did not reveal either facial palsy or other cranial nerve involvement. Pure tone audiometry revealed right anacusis and mild hearing loss in the left ear (Fig. 3c). No ABR was detected on the right side (Fig. 3d). Although left ABR showed preserved morphology, absolute latency delay of principal waves and prolonged interpeak intervals I-III (2.66 msec) and I-V (4.65 msec) were observed (Fig. 3d). Bi-thermal vestibular testing (Fitzgerald-Hallpike test) revealed right vestibular hypo-reflexia. DPOAEs were present in the left ear only. Prednisone dose was then increased to 37.5 mg/day with complete recovery of right auricle hypoaesthesia, but no change in the hearing threshold was measurable. Serum ACE levels were within the normal range.

The patient was examined one month later because of sudden left hearing loss. Pure tone audiometry confirmed the right anacusis and showed a moderate hearing loss in the left ear. DPOAEs in the left ear were still present. ABR parameters were similar to previous findings. Prednisone dose was increased to 70 mg/day with some hearing improvement within a few days. Lumbar puncture showed increased proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (142 g/l; upper normal limit 45 g/l). CSF glucose levels were within the limits, as were lymphocytes.

The patient underwent a new gadolinium enhanced cerebral MRI. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images demonstrated bilateral enhancement along the internal auditory meatus (IAM, Fig. 4a). No other lesions were detectable. MRI was repeated 2 months later showing further, widespread evolution of CNS lesions. Post-contrast T1-weighted images revealed diffuse enhancement of basal leptomeningeal, along the myelinic sheath of both optical nerves, of trigeminal nerves, and along the pial surfaces of the cerebellar folia (Fig. 4b). T2-weighted images revealed reduced signal intensity within the lateral and posterior semicircular canals (LSC and PSC) and the cochlea on the right. Absence of endolabyrinthic fluids on the right was demonstrated by T2-cis weighted/T2-volumetric sequences (Fig. 4c). The patient was scheduled for close follow-up, and his hearing has remained stable over 8 months.

Fig. 4.

Gadolinium enhanced cerebral MRI. a) December 2009; Axial contrast- enhanced T1-weighted images showing enhancement along internal auditory meatus (IAM) bilaterally (a, white arrows); b and c: February 2010; b) Post-contrast T1-weighted images revealing diffuse enhancement of basal leptomeningeal, of trigeminal nerves (b, white arrows) and along the pial surfaces of the cerebellar folia (b, black arrows); c) T2-weighted images showing reduced signal intensity within the lateral and posterior semicircular canals (LSC and PSC) and cochlea on the right (c, white arrows).

Discussion

Although cranial nerve neuropathy, especially affecting facial and optic nerves, is a common finding in up to 80% of neuro-sarcoidosis patients, eighth nerve involvement is seldom reported 1 2 5. To date, 18 case reports of SHL in sarcoidosis have been described in the English literature 9-13.

According to Zajicek criteria, the neurological symptoms experienced by our patients, both affected by systemic sarcoidosis, are consistent with a diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis 7. In Case 1, unilateral facial palsy and SHL, the two together were the first clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis. Absence of symptoms of systemic sarcoidosis and normal MRI led to a significant delay in diagnosis and the first ten-days' treatment with prednisone, was clearly insufficient to prevent hearing deterioration.

As far as concerns Case 2, the patient had already had systemic sarcoidosis diagnosed and was under immunosuppressive therapy when sudden mild hearing loss occurred in the right ear. Normal ABRs suggested a cochlear site of the lesion, that evolved to right sudden anacusis, vestibular hyporeflexia and absence of ABRs within 6 months. Subclinical progression of neurological involvement, although not accompanied by symptoms, was suspected in the presence of abnormal prolongation of inter-peak intervals of ABRs that appeared in the left ear. ABR abnormalities even in asymptomatic patients have been reported in a few cases 6 14. If found, they should alert the clinician to the possibility of evolution of the neurosarcoidosis, in order that a close follow-up can be planned and steroid treatment started as early as possible to avoid granuloma and ensuing scar formation in the neural tissue 6. Once sudden left hearing loss occurred, prednisone dosage was promptly increased obtaining only partial hearing improvement. Changes in ABRs preceding sudden hearing loss, could be explained histologically by perineural perivascular lymphocytic and granulomatous inflammation at the junction of the eighth nerve with the brain as described in autopsy reports 8.

Regarding cerebral gadolinium enhanced MRI, this was normal in Case 1, whereas in Case 2 only repetition and follow-up studies confirmed evolution of CNS lesions. Lack of abnormality on cerebral MRI despite symptoms of CNS involvement may be due to extra-cranial involvement of cranial nerves, to initially minimal perineural inflammatory infiltration or to the presence of granulomas too small to be detected by current imaging techniques 15. In conclusion, neurosarcoidosis should be kept in mind in differential diagnosis of SHL. Often accompanying symptoms develop and the diagnosis requires several days before being established, but, if confirmed, high dose corticosteroids should be started as soon as possible to prevent cochlear and neural destruction, thus profound hearing loss. Once profound deafness occurs, cochlear implant is probably not an option for restoring hearing in these patients.

Acknowledgement

Authors are grateful to Ms Manuela Spagnol for her constant and valid help with collection of patient data.

References

- 1.James DG, Sharma OP. Neurological complications of sarcoidosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1967;60:1169–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stern BJ, Krumholz A, Johns C, et al. Sarcoidosis and its neurological manifestations. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:909–917. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060080095022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah R, Roberson GH, Curé JK. Correlation of MR imaging findings and clinical manifestations in neurosarcoidosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:953–961. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen RKA, Sellars RE, Sandstrom P. A prospective study of 32 patients with neurosarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20:118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph FG, Scolding NJ, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: a study of 30 new cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:297–304. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.151977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oksanen V. Neurosarcoidosis: clinical presentations and course in 50 patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1986;73:283–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1986.tb03277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis - diagnosis and management. Q J Med. 1999;92:103–117. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babin RW, Liu C, Aschenbrener C. Histopathology of sensory deafness in neurosarcoidosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93:389–393. doi: 10.1177/000348948409300421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colvin IB. Audiovestibular manifestations of sarcoidosis: A review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:75–82. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000184580.52723.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rheault MN, Manivel JC, Levine SC, et al. Sarcoidosis presenting with hearing loss and granulomatous interstitial nephritis in an adolescent. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:1323–1326. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0153-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markert JM, Powell K, Tubbs RS, et al. Necrotizing neurosarcoid: three cases with varying presentations. Clin Neuropathol. 2007;26:59–67. doi: 10.5414/npp26059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.John S, Yeh S, Lew JC, et al. Protean manifestations of pediatric neurosarcoidosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2009;44:469–470. doi: 10.3129/i09-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souliere CR, Kava CR, Barrs DM. Sudden hearing loss as the sole manifestation of neurosarcoidosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:376–381. doi: 10.1177/019459989110500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gott PS, Kumar V, Kadakia J, et al. Significance of multimodality evoked potential abnormalities in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1997;14:159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman JL, Stern BJ. Sarcoidosis of the CNS: Comparison of Unenhanced and Enhanced MR Images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:1293–1301. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.6.2122683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]