Abstract

Objective

The first objective is to detail the prevalence of PTSD over a decade of follow-up for those in both study groups. The second is to determine time-to-remission, recurrence, and new onset of PTSD and the third is to assess the relationship between sexual adversity and the likelihood of remission and recurrence of PTSD.

Method

The SCID I was administered to 290 borderline inpatients and 72 axis II comparison subjects during their index admission and re-administered at five contiguous two-year follow-up periods.

Results

The prevalence of PTSD declined significantly over time for patients with BPD (61%). Over 85% of borderline patients meeting criteria for PTSD at baseline experienced a remission by the time of the 10-year follow-up. Recurrences (40%) and new onsets (27%) were less common. A childhood history of sexual abuse significantly decreased the likelihood of remission from PTSD and an adult history of sexual assault significantly increased the likelihood of a recurrence of PTSD.

Conclusion

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that PTSD is not a chronic disorder for the majority of borderline patients. They also suggest a strong relationship between sexual adversity and the course of PTSD among patients with BPD.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Longitudinal Course

Clinical experience suggests that reported childhood adversity, adult experiences of violence, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are common among patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). While research findings support the relationship between childhood and adult adversity and BPD (1, 2), only seven cross-sectional studies have assessed the prevalence of PTSD in samples of criteria-defined patients with BPD (3–9). In general, these studies found that PTSD was quite common, with a range of 25–55.9% and a median prevalence of 46.9%. In addition, only two longitudinal studies have assessed the course of PTSD in a sample of well-defined patients with BPD (10, 11). In the first of these studies—the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study or CLPS—it was found that BPD remitted more rapidly over two years of prospective follow-up in patients with remitted PTSD than those with unremitted PTSD (10). In the second of these studies—the McLean Study of Adult Development or MSAD, it was found that the prevalence of PTSD declined significantly over six years of prospective follow-up but remained significantly higher among patients with BPD than among axis II comparison subjects (11). It was also found that the absence of PTSD at baseline was a significant predictor of a faster time-to-remission of BPD.

Aims of the Study

The current study, which is an extension of the MSAD study mentioned above, is the first longitudinal study to assess the prevalence of PTSD over 10 years of prospective follow-up in a large and well-defined sample of patients with BPD and axis II comparison subjects. It is also the first study to assess time-to-remission, time-to-recurrence, and time-to-new onset of PTSD in patients with BPD followed prospectively for a decade. In addition, it is the first study to assess the relationship between sexual adversity in childhood and adulthood and the likelihood of remission and recurrence of PTSD among borderline patients meeting criteria for this co-occurring disorder at study entry.

Methods

The current study is part of the McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD), a multifaceted longitudinal study of the course of borderline personality disorder. All subjects were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. Each patient was first screened to determine that he or she: 1) was between the ages of 18–35; 2) had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher; 3) had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and 4) was fluent in English.

After the study procedures were explained, written informed consent was obtained. Each patient then met with a masters-level interviewer blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses for a thorough diagnostic assessment. Three semistructured diagnostic interviews were administered. These diagnostic interviews were: 1) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (12), 2) the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) (13), and 3) the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (14) (DIPD-R). The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of all three of these measures have been found to be good-excellent (15, 16).

At each of five follow-up waves, separated by 24 months, axis I and II psychopathology was reassessed via interview methods similar to the baseline procedures by clinically experienced MA-level or BA-level staff members blind to baseline diagnoses. After informed consent was obtained, our diagnostic battery was readministered (with the SCID I focusing on the past two years and not as at baseline, lifetime axis I psychopathology). The follow-up interrater reliability (within one generation of follow-up raters) and follow-up longitudinal reliability (from one generation of raters to the next) of these three measures have also been found to be good-excellent (15, 16).

Raters blind to diagnostic status, who ranged from BA-level to doctoral-level, administered two measures of adversity at baseline: one pertaining to childhood experiences (before the age of 18)--the Revised Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (CEQ-R) (1) and one pertaining to adult experiences of adversity and the severity of childhood sexual abuse--the Abuse History Interview (AHI) (2, 17). Both interviews have been found to have good inter-rater and test-retest reliability (1, 2, 17).

Definition of Remission, Recurrence, and New Onset of PTSD

We defined remission as any two-year period (any follow-up period) in which the criteria for PTSD were no longer met. We chose this length of time at the start of the study to mirror our definitions of remission of BPD and its constituent symptoms (18). In addition, a recurrence or new onset was defined as any one-month period in which the criteria for PTSD were met after a two-year remission or for the first time.

Statistical Analyses

Generalized estimating equations, with diagnosis and time as main effects, were used in longitudinal analyses of prevalence data. Tests of diagnosis by time interactions were conducted. These analyses modeled the log prevalence, yielding an adjusted relative risk ratio (RRR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for diagnosis and time. Gender was also included in these analyses as a covariate as patients with BPD were significantly more likely than axis II comparison subjects to be female. Alpha was set at the p<0.05 level, two-tailed.

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator (of the survival function) was used to assess time-to-remission of PTSD, time-to-recurrence of this disorder, and time-to-new onsets. We defined time-to-remission of PTSD as the follow-up period at which remission was first achieved. Thus, possible values for this time-to-remission measure were 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 years, with time=2 years for persons first achieving a remission of PTSD during the first follow-up period, time=4 years for persons first achieving such a remission during the second follow-up period, etc. We defined time-to-new onset in a like manner. We defined time-to-recurrence in a somewhat different manner (i.e., the number of years after a remission had been achieved that recurrence first occurred). Thus, time-to-recurrences were 2, 4, 6, or 8 years after first remission. Finally, baseline and time-varying predictors of time-to-remission and time-to-recurrence among patients with BPD were assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model; these analyses yield bivariate associations expressed in terms of hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Two hundred and ninety patients met both DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for BPD and 72 met DSM-III-R criteria for at least one nonborderline axis II disorder (and neither criteria set for BPD). Of these 72 comparison subjects, 4% met DSM-III-R criteria for an odd cluster personality disorder, 33% met DSM-III-R criteria for an anxious cluster personality disorder, 18% met DSM-III-R criteria for a nonborderline dramatic cluster personality disorder, and 53% met DSM-III-R criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified (which was operationally defined in the DIPD-R as meeting all but one of the required number of criteria for at least two of the 13 axis II disorders described in DSM-III-R).

Baseline demographic data have been reported before (18). Briefly, 77.1% (N=279) of the subjects were female and 87% (N=315) were white. The average age of the subjects was 27 years (SD=6.3), the mean socioeconomic status was 3.3 (SD=1.5) (where 1=highest and 5=lowest) (19), and their mean Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score (with lower scores on a scale ranging from 0–100 indicating poorer outcomes) was 39.8 (SD=7.8) (indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood).

In terms of continuing participation, 90.4% (N=309) of surviving patients were reinterviewed at all five follow-up waves. More specifically, 91.9% of surviving patients with BPD (249/271) and 84.5% of surviving axis II comparison subjects (60/71) were evaluated six times (baseline and five follow-up periods).

Table 1 details the prevalence of PTSD reported by patients with BPD and axis II comparison subjects over 10 years of prospective follow-up. As can be seen, 58% of patients with BPD (and about a quarter of axis II comparison subjects) reported a history of PTSD at baseline. By the time of their 10-year follow-up, these prevalence rates had declined to 21% and 3% respectively. The relative difference of 2.14 for diagnosis indicates that patients with BPD were just over two times more likely than axis II comparison subjects to have such a history at baseline. The relative difference of 0.12 for time indicates that the relative change from baseline to 10-year follow-up resulted in an approximately 88% (or [1 – 0.12]×100%) decline in the prevalence of PTSD for axis II comparison subjects. In contrast, the significant interaction between diagnosis and time of 3.22 indicates that the relative decline from baseline to 10-year follow-up is approximately 61% (or [1 – 0.12×3.22]×100%) for patients with BPD. That is, the decline in the prevalence of PTSD for patients with BPD is discernibly less steep than for axis II comparison subjects.

Table 1.

Prevalence of PTSD among Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Axis II Comparison Subjects Over Ten Years of Prospective Follow-up

| Patients with BPD | Axis II Comparison Subjects | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (N=290) |

2 Yr FU (N=275) |

4 Yr FU (N=269) |

6 Yr FU (N=264) |

8 Yr FU (N=255) |

10 Yr FU (N=249) |

BL (N=72) |

2 Yr FU (N=67) |

4 Yr FU (N=64) |

6 Yr FU (N=63) |

8 Yr FU (N=61) |

10 Yr FU (N=60) |

RRR Diagnosisa Timeb Interactionc |

95 % CI Diagnosis Time Interaction |

|

| Post-traumatic stress disorder |

58.3 (N=169) |

51.3 (N=141) |

42.4 (N=114) |

34.9 (N=92) |

25.5 (N=65) |

20.9 (N=52) |

25.0 (N=18) |

16.4 (N=11) |

12.5 (N=8) |

4.8 (N=3) |

4.9 (N=3) |

3.3 (N=2) |

2.14 0.12 3.22 |

1.39, 3.30 0.05, 0.26 1.41, 7.34 |

P-value for diagnosis = 0.001

P-value for time < 0.001

P-value for diagnosis × time interaction= 0.005

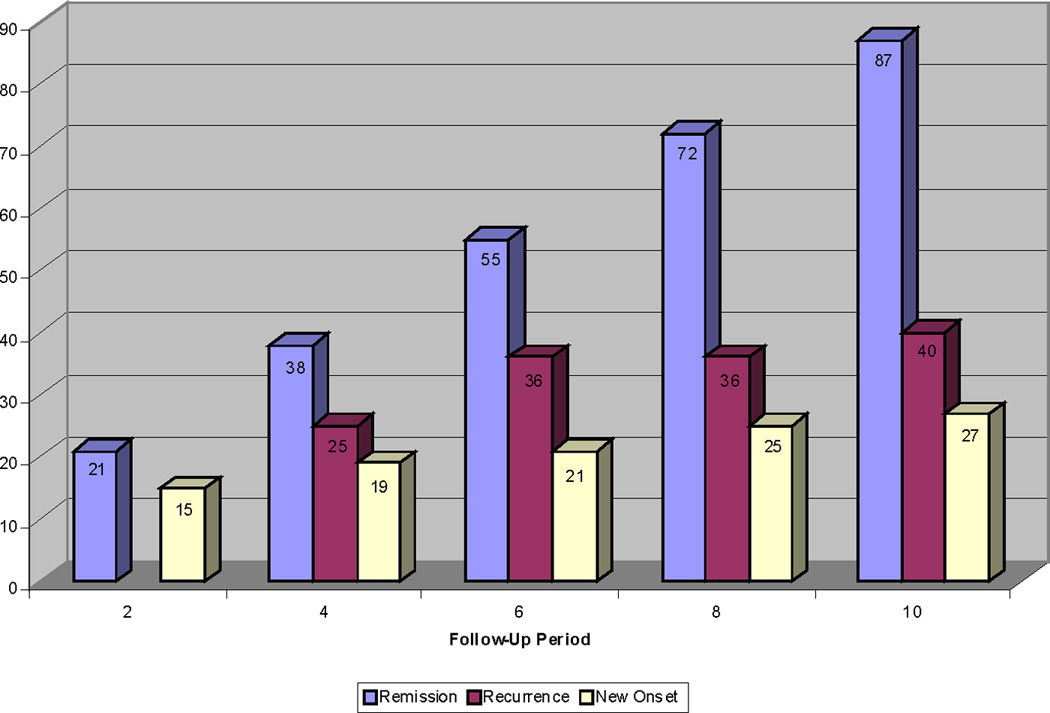

Figure 1 details the rates of remission, recurrence and new onsets of PTSD for patients with BPD who met criteria for this disorder at baseline (N=163). Of these 163 patients, 83.4% (N=136) attributed their PTSD to a childhood history of sexual abuse, 46% (N=75) attributed their PTSD to adult sexual assault, and 36.8% (N=60) attributed it to both. An additional 12 patients, without a history of sexual trauma, attributed their PTSD to a variety of other causes, such as watching a parent being murdered. As can be seen, it is estimated that 87% of patients with BPD reporting PTSD at baseline experience a remission by the time of the 10-year follow-up (N=123). In addition, it is estimated that 40% of patients with BPD reporting a remission of PTSD later had a recurrence (N=30) of this disorder. The figure also shows that 27% of patients with BPD who did not report having PTSD at baseline (N=127) are estimated to have a new onset (N=30) of PTSD. (Note that the estimated rates of remission, recurrence, and new onsets cannot be directly determined using the numbers presented above because of censoring [i.e., subjects lost to follow-up].)

Figure 1. Rates of Remission, Recurrence and New Onsets of PTSD Among Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder over 10 Years of Prospective Follow-Up.

Note: Since a recurrence can only occur after a remission, there is no possibility of a recurrence occurring at the 2-year follow up. Even though recurrence are displayed in this figure at the 4, 6, 8, and 10-year follow-up periods, these recurrences are actually occurring 2, 4, 6, and 8 years after the remission.

Of these 30 BPD patients with new onsets, 20 (20/30=66.7%) experienced a delayed onset of PTSD that they attributed to either childhood physical/sexual abuse (16/20=80.0%) and/or an adult history of physical assault/rape (5/20=25.0%) that they had always remembered and had reported at baseline (1, 2). Of the 10 remaining patients, nine attributed the onset of PTSD to a traumatic event that occurred during the years of follow-up. More specifically, six patients with BPD reported being raped, one reported being physically abused by a romantic partner, one reported being physically assaulted at work, and one reported witnessing extreme physical violence. Only one borderline patient attributed the new onset of PTSD to recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse.

Only 15 axis II comparison subjects met criteria for PTSD at baseline. All 15 had a remission during the years of follow-up and of these 15, six had a recurrence. In terms of new onsets, only five axis II comparison subjects of the 57 who did not meet criteria at baseline had a new onset of PTSD over the years of follow-up.

In terms of predictors of time-to-remission among patients with BPD, it was found that the presence of childhood sexual abuse and the severity of that abuse were both significant predictors. More specifically, patients with a childhood history of sexual abuse were only half as likely to have a remission from PTSD (HR=0.53, 95%CI=0.30–0.93, z=−2.20, and p=0.028) when compared to those without such a history. For each five-point increase of the severity of childhood sexual abuse (on a scale of 0–19), the likelihood of remission of PTSD declined by about 21% (HR=0.79, 95%CI=0.68–0.94, z=−2.76, p=0.006). In contrast, neither the presence of a rape history as an adult (HR=0.69, 95%CI=0.46–1.05, z=−1.71, p=0.086) nor the combination of childhood sexual abuse and an adult rape history (HR=0.68, 05%CI=0.44–1.05, z=−1.74, p=0.082) was a statistically discernible predictor of time-to-remission of PTSD among study subjects with BPD.

In terms of baseline predictors of time-to-recurrence among patients with BPD, it was found that neither the presence of a history of childhood sexual abuse (HR=1.74, 95%CI=0.56–5.38, z=0.96, p=0.338) nor its severity (HR=1.18, 95%CI=0.85–1.63, z=1.00, p=0.319) was a significant predictor of the likelihood of such a recurrence. However, an adult rape history at baseline and the combination of a history of childhood sexual abuse and an adult rape history were both significant predictors of such a recurrence. More specifically, both an adult rape history (HR=2.53, 95%CI=1.13–5.67, z=2.25, p=0.025) and the combination of a childhood history of sexual abuse and an adult rape history (HR=2.47, 95%CI=1.10–5.52, z=2.19, p=0.028) doubled the likelihood of such a recurrence. In terms of sexual adversity occurring during the years of follow-up, it was found that those borderline patients who reported being sexually assaulted during the 10 years of prospective follow-up were almost 11 times (HR=10.9, 95%CI=3.3–36.7, z=3.87, p<0.001) more likely to experience a recurrence of PTSD than those who were not sexually assaulted during this decade.

Discussion

Five main findings have emerged from the results of this study. The first finding is that the prevalence of PTSD, which was about 7 times the prevalence of PTSD in the general population (20), declined significantly over time for patients with BPD (and axis II comparison subjects). More specifically, the prevalence of PTSD declined 61% for patients with BPD and 88% for axis II comparison subjects. These findings are consistent with and extend the findings of our six-year follow-up study of this sample (11).

The second main finding is that 87% of the patients with BPD meeting criteria for PTSD at baseline experienced a remission by the time of the 10-year follow-up. Our remission rate of 21% at two-year follow-up is almost identical to the 18% of primary care patients who reported a full remission of PTSD 24 months after study entry but substantially less than the 69% who reported a partial remission of PTSD during this time period (i.e., has residual symptoms of PTSD and psychosocial impairment) (21). In addition, this 21% remission rate is half the remission rate found at two-year follow-up in a community sample of adults in the US (22). It is also half the remission rate found in a community study of German adolescents and young adults reinterviewed three-four years after their initial assessment (23). These differences may be due to the fact that subjects in a primary care setting or a community sample may be less disturbed than those in a psychiatric sample. These differences may also be due to shorter length of remission in these earlier studies.

The third main finding is that 40% of patients with BPD who experienced a remission of PTSD later experienced a recurrence of PTSD. This is a new finding, suggesting that the majority of borderline patients with PTSD will have a remission so stable that it might be considered a recovery.

The fourth main finding is that 27% of patients with BPD who did not meet criteria for PTSD at baseline later developed a new onset of PTSD. Our rate of new onsets is about three times that found in a longitudinal study of holocaust survivors over ten years (10%) (24). It is also about five times the rate of new onsets of PTSD found in a sample of Vietnam veterans followed for 14 years (5.2%) (25). The reasons for these differences are not clear but may be related to the nature of the trauma or traumas experienced and/or the age at which these experiences occurred.

The fifth main finding is that remissions and recurrences of PTSD among borderline patients were significantly associated with sexual adversity. More specifically, the presence of childhood sexual abuse halved the likelihood of remission from PTSD. In contrast, a baseline rape history and a sexual assault during a follow-up period increased the likelihood of a recurrence of PTSD by a factor of two and 11 respectively. These findings are consistent with the findings of Perkonigg et al. (23) who found that a new traumatic event was associated with a chronic course of PTSD in community subjects who were 14–24 years of age at study entry.

The findings of this study have nosological implications. More specifically, Herman has suggested that chronic PTSD is a more useful diagnostic category than BPD as it might be less stigmatizing (26). However, the results of this study suggest that over a third of even the most disturbed patients with BPD do not meet criteria for PTSD after a decade of prospective follow-up. And that almost 90% of those with co-occurring PTSD at baseline have a remission lasting at least two consecutive years, indicating that their PTSD is not chronic in nature.

This study also has treatment implications. It would seem wise for mental health professionals treating patients with BPD and co-occurring PTSD to pay particular attention to the possibility that they might experience sexual assaults while in treatment as adults and that these assaults have a substantial likelihood of leading to a recurrence of PTSD that has remitted. The best way to deal with this risk factor is unclear. However, the development and/or strengthening of anticipatory skills might be a promising avenue to pursue.

This study has two main limitations. One limitation of this study is that all of the patients were seriously ill inpatients at the start of the study. Another limitation is that about 90% of those in both patient groups were in individual therapy and taking psychotropic medications at baseline and about 70% were participating in each of these outpatient modalities during each follow-up period (27). Thus, it is difficult to know if these results would generalize to a less disturbed group of patients or people meeting criteria for BPD who were not in treatment.

In terms of directions for future research, there are very few long-term studies of the course of PTSD. And these tend to be in individuals whose trauma occurred in adulthood, as a result of being in combat, a prisoner of war or POW, or a holocaust survivor (28–32). Clearly, it would be useful if additional studies of the long-term course of PTSD in borderline and other diagnostic groups were conducted, particularly PTSD associated with childhood adversity. Additional studies that determine the relationship over time of the course of PTSD and key symptoms of BPD, such as dissociation (33) and physically self-destructive acts (34), are also needed.

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that PTSD is not a chronic disorder for the majority of patients with BPD with co-occurring PTSD. These results also suggest a strong relationship between sexual adversity over the lifespan and the course of PTSD among patients with BPD.

Significant Outcomes

The lifetime prevalence of PTSD in this sample at the time of study entry was about 7 times the prevalence in the general US population.

The recurrence rate of 40% seems to imply that that the majority of borderline patients with PTSD will have a remission so stable that it might be considered a recovery.

67% of those with new onsets experienced a delayed onset of PTSD that they attributed to clearly remembered events that they had reported at baseline, 30% attributed the onset of PTSD to a traumatic event that occurred during the years of follow-up, and only 3% attributed the onset of PTSD to recovered memories of childhood abuse, indicating that these memories may play a minor role in the development of new onsets of PTSD in patients with BPD.

Borderline patients with a childhood history of sexual abuse were only half as likely to have a remission from PTSD when compared to those without such a history.

An adult rape history at baseline doubled the likelihood of a recurrence.

A sexual assault during the decade of follow-up increased the likelihood of a recurrence by a factor of 11.

Limitations

All subjects were initially inpatients and thus, the results of this study may not apply to less seriously ill outpatients.

The majority of the sample was in treatment and thus, the results may not generalize to untreated subjects.

All information about PTSD and BPD was provided by subjects

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants MH47588 and MH62169 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the Fellowship Persönlichkeitsstörungen by the Gesellschaft zur Erforschung und Therapie von Persönlichkeitsstörungen e.V. and the Asklepios Kliniken Hamburg GmbH.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zanarini MC, Williams AA, Lewis RE, Reich RB, Vera SC, Marino MF, Levin A, Yong L, Frankenburg FR. Reported pathological childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1101–1106. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Marino MF, Haynes MC, Gunderson JG. Violence in the lives of adult borderline patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187:65–71. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199902000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueser KT, Goodman LB, Trumbetta SL, Rosenberg SD, Osher C, Vidaver R, Auciello P, Foy DW. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:493–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V. Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1733–1739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Axis I diagnostic comorbidity and borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40:245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline Axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102:256–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yen S, Shea MT, Battle CL, Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Dolansewell R, Skodol AE, Grilo CM, Gunderson JG, Sanislow CA, Zanarini MC, Bender DS, Rettew JB, Mcglashan TH. Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190:510–518. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golier JA, Yehuda R, Bierer LM, Mitropoulou V, New AS, Schmeidler J, Silverman JM, Siever LJ. The relationship of borderline personality disorder to posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic events. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:2018–2024. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shea MT, Stout RL, Yen S, Pagano ME, Skodol AE, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Bender DS, Zanarini MC. Associations in the course of personality disorders and Axis I disorders over time. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:499–508. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Axis I comorbidity in patients with borderline personality disorder: 6-year follow-up and prediction of time to remission. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2108–2114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanarini MC, Gunderson J, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: discriminating BPD from other Axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, Gunderson JG. The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: interrater and test-retest reliability. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1987;28:467–480. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:369–374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanarini MC, Yong L, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Marino MF, Vujanovic AA. Severity of reported childhood sexual abuse and its relationship to severity of borderline psychopathology and psychosocial impairment among borderline inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:381–387. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollingshead AB. Two factor index of social position. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zlotnick C, Rodriguez BF, Weisberg RB, Bruce SE, Spencer MA, Culpepper L, Keller MB. Chronicity in posttraumatic stress disorder and predictors of the course of posttraumatic stress disorder among primary care patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:153–159. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000110287.16635.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkonigg A, Pfister H, Stein MB, Hofler M, Lieb R, Maercker A, Wittchen HU. Longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1320–1327. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yehuda R, Schmeidler J, Labinsky E, Bell A, Morris A, Zemelman S, Grossman RA. Ten-year follow-up study of PTSD diagnosis, symptom severity and psychosocial indices in aging holocaust survivors. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koenen KC, Stellman JM, Stellman SD, Sommer JF., Jr Risk factors for course of posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans: a 14-year follow-up of American Legionnaires. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:980–986. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herman JL, Van Der Kolk BA. Traumatic antecedents of borderline personality disorder. In: van der Kolk BA, editor. Psychological Trauma. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1987. pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hörz S, Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. Ten-year use of mental health services by patients with borderline personality disorder and with other axis II disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:612–616. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.6.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dirkzwager AJ, Bramsen I, Van Der Ploeg HM. The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among aging military veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2001;189:846–853. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200112000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shlosberg A, Strous RD. Long-term follow-up (32 Years) of PTSD in Israeli Yom Kippur War veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193:693–696. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000180744.97263.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon Z, Shklar R, Singer Y, Mikulincer M. Reactions to combat stress in Israeli veterans twenty years after the 1982 Lebanon war. The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease. 2006;194:935–939. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000249060.48248.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Toole BI, Catts SV, Outram S, Pierse KR, Cockburn J. The physical and mental health of Australian Vietnam veterans 3 decades after the war and its relation to military service, combat, and post-traumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:318–330. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solomon Z, Horesh D, Ein-Dor T. The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters among war veterans. The Journal Of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70:837–843. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Jager-Hyman S, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. The course of dissociation for patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects: a 10-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G, Weinberg I, Gunderson JG. The 10-year course of physically self-destructive acts reported by borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117:177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]