Abstract

Objective

The first purpose of this study was to determine time-to attainment of recovery from borderline personality disorder and the second was to determine the stability of this important outcome.

Method

290 inpatients meeting both Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines and DSM-III-R criteria for the disorder were assessed during their index admission using a series of semistructured interviews and self-report measures. The same instruments were readministered at five contiguous two-year time periods.

Results

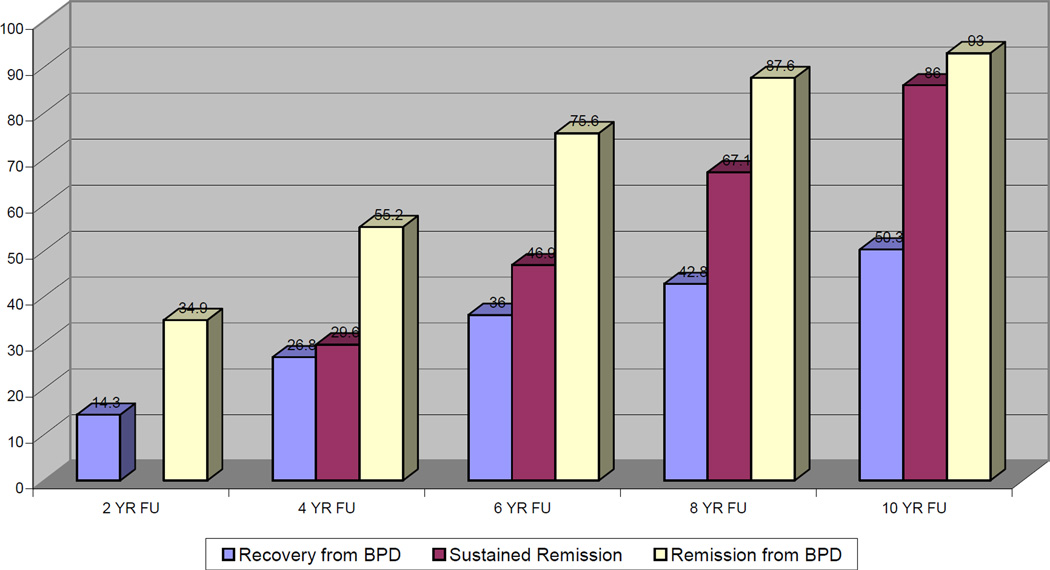

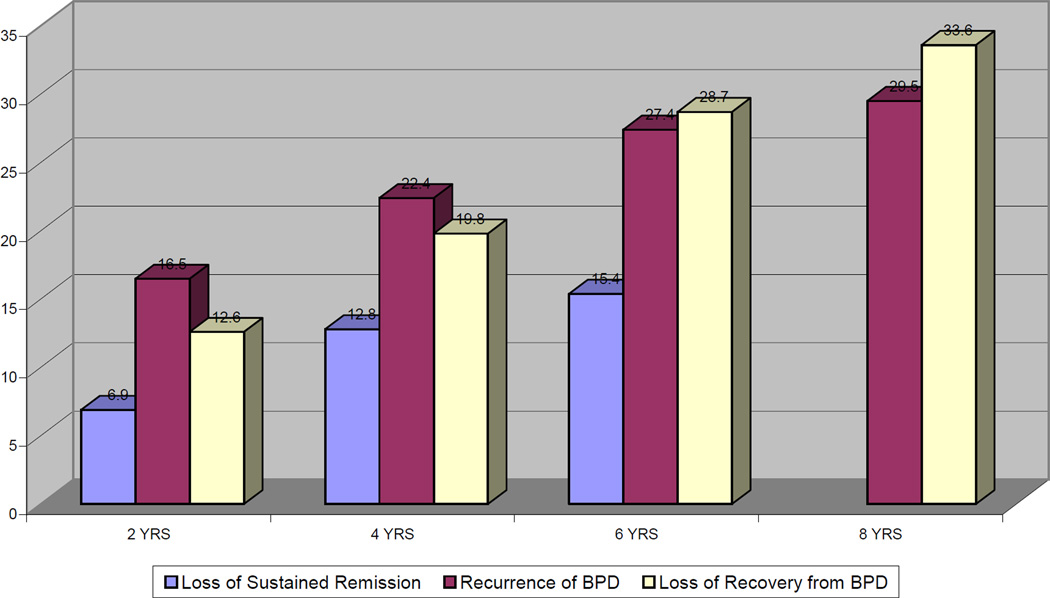

All told, 50% of the borderline patients studied achieved a recovery from borderline personality disorder—an outcome that required being symptomatically remitted and having good social and vocational functioning during the past two years. In contrast, 93% of borderline patients attained a symptomatic remission lasting two years and 86% attained a sustained symptomatic remission that lasted four years. In terms of stability of these outcomes, 34% of borderline patients lost their recovery from borderline personality disorder. A similar 30% had a symptomatic recurrence after a two-year long remission but only 15% experienced a symptomatic recurrence after a sustained remission.

Conclusions

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that recovery from borderline personality disorder combining both symptomatic remission and good psychosocial functioning seems difficult for many borderline patients to attain. These results also suggest that such a recovery once attained is relatively stable over time.

Clinical experience suggests that some patients with borderline personality disorder both exhibit only mild symptoms and function well psychosocially over time. Clinical experience also suggests that others remain quite symptomatic. In addition, they may be unable to work or go to school successfully. They may also become increasingly socially isolated or move from one contentious relationship to another.

In terms of empirical evidence, four large-scale, long-term, follow-back studies of the longitudinal course of borderline personality disorder were conducted in the 1980s (1–4). The borderline patients in these studies received a mean score of 63–67 on either the Health Sickness Rating Scale (5) or the Global Assessment Scale (6)—precursors to the Global Assessment of Functioning. This consistent finding has usually been interpreted to mean that the average borderline patient has attained a reasonably good overall outcome a mean of 14–16 years after his or her index admission.

More recently, NIMH had funded two large-scale, prospective studies of the long-term course of borderline personality disorder—the McLean Study of Adult Development or MSAD (7) and the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study or CLPS (8). In terms of global functioning, the former study found steady, if modest, overall improvement over six years of prospective follow-up (9); moving from a mean Global Assessment of Functioning score in the incapacitated range at baseline to a mean Global Assessment of Functioning score in the fair range at six-year follow-up. In contrast, the latter study found that borderline patients continued to function in the fair range of global functioning over two years of prospective follow-up (10).

The current study, which is an extension of the McLean Study of Adult Development mentioned above, assesses recovery from borderline personality disorder in a sample of 290 borderline patients who were initially inpatients. It also assesses symptomatic remission and sustained symptomatic. In addition, it assesses both the time-to-attainment of these outcomes and time-to-loss of these outcomes.

Methods

All subjects were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. Each patient was first screened to determine that he or she: 1) was between the ages of 18–35; 2) had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher; 3) had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and 4) was fluent in English.

After the study procedures were explained, written informed consent was obtained. Each patient then met with a masters-level interviewer blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses for a thorough psychosocial and treatment history as well as diagnostic assessment. Four semistructured interviews were administered. These interviews were: 1) the Background Information Schedule (11), 2) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (12), 3) the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (13), and 4) the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (14). The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Background Information Schedule (9) and of the three diagnostic measures (15,16) have all been found to be good-excellent.

At each of five follow-up waves, separated by 24 months, psychosocial functioning and treatment utilization as well as axis I and/II psychopathology were reassessed via interview methods similar to the baseline procedures by staff members blind to previously collected information. After informed consent was obtained, our diagnostic battery was readministered as well as the Revised Background Information Schedule—the follow-up analog to the Background Information Schedule administered at baseline (17). Good-excellent follow-up (within a generation of raters) and longitudinal (between generations of raters) inter-rater reliability was maintained throughout the course of the study for variables pertaining to psychosocial functioning and treatment use (9). Good-excellent follow-up and longitudinal inter-rater reliability was also maintained for both axis I and II disorders (15,16).

Definition of Recovery from Borderline Personality Disorder

We selected a Global Assessment of Functioning score of 61 or higher (which none of our subjects had at baseline) as our measure of recovery for two reasons. First, it is the outcome used by the four follow-back studies described above. Second, it offers a reasonable description of a good overall outcome (i.e., some mild symptoms or some difficulty in social, occupational, or school functioning, but generally functioning pretty well, has some meaningful interpersonal relationships).

We operationalized this score to enhance its reliability and meaning. More specifically, to be given a Global Assessment of Functioning score of 61 or higher, a borderline subject typically had to be in remission (see below for definition), have at least one emotionally sustaining relationship with a close friend or life partner/spouse, and was able to work or go to school consistently, competently, and on a full-time basis.

Definition of Remission and Sustained Remission from Borderline Personality Disorder

We defined remission as no longer meeting study criteria for borderline personality disorder (Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines and DSM-III-R) for a period of two years or more (or at least one follow-up period). We defined sustained remission as no longer meeting study criteria for a period of four years or more (or at least two consecutive follow-up periods).

Statistical Analyses

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator (of the survival function) was used to assess time-to-remission and time-to-recovery from borderline personality disorder. We defined time-to-attainment of these outcomes as the follow-up period at which these outcomes were first achieved. Thus, possible values for these outcomes were 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 years, with time=2 years for persons first achieving remission or recovery from borderline personality disorder during the first follow-up period, time=4 years for persons first achieving remission or recovery from borderline personality disorder during the second follow-up period, etc.

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator was also used to assess time-to-attainment of a sustained symptomatic remission. We defined time-to-attainment of a sustained symptomatic remission as the follow-up period at which this outcome was first achieved. Thus, possible values for this outcome were 4, 6, 8, or 10 years, with time=4 years for persons first achieving this outcome during the second follow-up period, time=6 years for persons first achieving this outcome during the third follow-up period, etc.

In addition, the Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator was used to assess time- to-recurrence after a two-year remission, time-to-loss of recovery, and time-to-loss of a sustained remission. Possible values for recurrence and loss of recovery from borderline personality disorder were 2, 4, 6, or 8 years after first attaining these outcomes. Possible values for loss of sustained symptomatic remission were 2, 4, or 6 years after first attaining this outcome.

Results

Two hundred and ninety patients met both Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines and DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder. In terms of baseline demographic data, 80.3% (N=233) of the subjects were female and 87.2% (N=253) were white. The average age of the borderline subjects was 26.9 years (SD=5.8), their mean socioeconomic status was 3.4 (SD=1.5) (where 1=highest and 5=lowest), and their mean Global Assessment of Functioning score was 38.9 (SD=7.5) (indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood).

In terms of continuing participation, 275 borderline patients were reinterviewed at two years, 269 at four years, 264 at six years, 255 at eight years, and 249 at ten years. At the ten-year assessment, 41 borderline patients were no longer in the study: 12 had committed suicide, seven died of other causes, nine discontinued their participation, and 13 were lost to follow-up. All told, 91.9% (N=249/271) of surviving borderline patients were reinterviewed at all five follow-up waves.

Figure 1 details time-to-attainment of our three outcomes: symptomatic remission, sustained symptomatic remission, and recovery from borderline personality disorder. As can be seen, 93% of borderline patients attained a symptomatic remission lasting at least two years and 86% attained a sustained symptomatic remission lasting at least four years. In contrast, only 50% of borderline patients attained a recovery from borderline personality disorder—involving good social and vocational functioning as well as no longer meeting study criteria for borderline personality disorder in a two-year follow-up period.

Figure 1.

Time-to-attainment of Remission from BPD, Sustained Remission from BPD, and Recovery from BPD

Figure 2 details time-to-loss of our three outcomes. As can be seen, about 34% of borderline patients lost their recovery and about 30% experienced a symptomatic recurrence after a two-year remission. However, only about 15% lost their sustained remission from borderline personality disorder.

Figure 2.

Time-to-loss of Remission from BPD, Sustained Remission from BPD, and Recovery from BPD

Discussion

Two main findings have emerged from this study. The first is that only half of the borderline patients in this study experienced a recovery from borderline personality disorder, which we defined as requiring a two-year symptomatic remission and the attainment of good social and vocational functioning. This finding stands in contrast to the fact that over 90% of borderline patients experienced a two-year symptomatic remission and 86% experienced a four-year symptomatic remission. Taken together, these results seem to suggest that good social and vocational functioning is more difficult to attain than substantial symptomatic reduction; a formulation first clearly articulated by Skodol et al. (10). These results also seem to suggest that most borderline patients who achieve a two-year remission from borderline personality disorder also achieve a remission lasting at least four years or two consecutive follow-up periods.

It might be argued that either of our definitions of remission could actually be seen as recoveries, particularly sustained remission lasting four years or more. This is so because studies of axis I disorders often describe remissions or even recoveries in terms of weeks and months of decreased symptomatology (18,19). However, our definition of recovery, which includes good social and vocational functioning as well as two years of symptomatic remission, is more consistent with what patients and their families believe is the goal of treatment and the desired outcome of maturation or at least, the passage of time.

This set of results is consistent with clinical experience. More specifically, many patients exhibit far fewer borderline symptoms as time progresses; a result found in a recent 10-year report from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (20). However, their psychosocial functioning remains or becomes impaired over the years. Given this, it is not surprising that only half of borderline patients attained all three aspects of recovery from borderline personality disorder: symptomatic remission and the attainment of both social and vocational competence. However, it is sobering that only half of borderline patients achieved a fully functioning adult adaptation with only mild symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Additionally, this set of findings suggests that the overall prognosis for many borderline patients is somewhat more guarded than the findings of the long-term follow-back studies conducted more than 20 years ago were thought to mean. However, this discrepancy is not surprising given the more thorough prospective assessments of the current study.

The second main finding is that recovery from borderline personality disorder was relatively stable, with only about 34% of those attaining such a recovery later losing one or more aspects of this multifaceted outcome. While this rate was very similar to the 30% rate found for symptomatic recurrence after a two-year long remission, it was twice the 15% found for loss of a sustained four-year long symptomatic remission.

In fact, each of the three rates of recurrence studied are lower than those found for common axis I disorders studied longitudinally, such a major depression (21) or dysthymic disorder (18). Additionally, the high rate of sustained symptomatic remission (86%) and the low rate of symptomatic recurrence after such a four-year long remission (15%) are two of the most optimistic findings about borderline personality disorder to date.

Taken together, the results of this study have implications for the treatment of borderline patients. While clinical experience suggests that clinicians are often aware that their borderline patients have trouble achieving a good overall long-term outcome, clinical experiences also suggests that their psychosocial deficits are rarely the focus of treatment. Rather the emphasis is on symptom reduction and management. Yet our results suggest that remissions are far more common than the good psychosocial functioning needed to achieve a good global outcome.

It would seem wise for those treating borderline patients to consider a rehabilitation model of treatment for these psychosocial deficits (22). Such a model would focus on helping borderline patients to attain work, make friends, take care of their physical health, and develop interests that would help to fill their leisure time productively. And such an approach could be an added form of treatment and not one directly competing for primacy with a treatment focused on symptom remission.

If this rehabilitation approach was adopted and proved effective, it could limit the relatively high percentage of borderline patients supporting themselves on Social Security disability benefits (23). It might also help to alleviate some of the feelings of worthlessness and failure that permeate the self-concept of many borderline patients who have failed to achieve the life that others and they themselves had once expected.

This study has a number of limitations. The first is that all subjects were initially inpatients. It may well be that borderline patients who have never been hospitalized are less impaired psychosocially and thus, more likely to attain a good global outcome over time. The second is that the majority of the sample was in treatment over time and thus, the results may not generalize to untreated subjects.

In terms of future studies, we plan on assessing time-to attainment of a Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score of 71 or higher when we have completed further waves of follow-up. In this way, we will be able to determine if our rates of this overall outcome are similar to the 16% and 42% found by McGlashan and Stone respectively in their long-term follow-back studies (1–4).

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that recovery from borderline personality disorder combining both symptomatic remission and good psychosocial functioning seems difficult for many borderline patients to attain. These results also suggest that such a recovery once attained is relatively stable over time.

Vignette 1.

Ms. A was in her early 20s at the time of her index admission. She came from a middle class background marked by parental alcoholism and childhood adversity. She had had numerous prior hospitalizations and met criteria for co-occurring PTSD, panic disorder, and EDNOS. While the severity of her borderline psychopathology increased over the first two years of follow-up, she achieved a remission of BPD by the time of the four-year follow-up. Her psychosocial functioning also improved during this period as she worked steadily at a demanding job, saw friends regularly, and met her future husband. Her remission and recovery from BPD were stable throughout the next six years. She no longer met criteria for any axis I disorder. She continued in once weekly psychotherapy but no longer took any psychotropic medication. She is currently married, the mother of several children, and works outside the home on a part-time basis. She describes herself as happy and her family as a “treasure” for which she is very grateful. She is described by others as likeable and resilient.

Vignette 2.

Ms. B was in her mid 30s at the time of her index admission. She came from an upper middle class background and reports being subjected to extreme cruelty and violence during latency and adolescence. She had had over 10 prior hospitalizations and met criteria for nine axis I disorders, including mood, anxiety, somatoform, and eating disorders. She experienced a remission of BPD at four and six-year follow-up but she never recovered from BPD. While having friends, she never dated or worked. Rather, she supported herself through disability payments. She experienced a recurrence of BPD at eight and 10-year follow-up, which she attributed to the loss of a trusted member of her treatment team. After this loss, her physical health deteriorated. In addition, she no longer saw her friends on a regular basis. Rather, she spent most of her time either home alone or going to appointments with numerous medical specialists and mental health providers. She describes herself as permanently damaged, yet “hopeful” about the future. Others describe her as eager for connection but fragile.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIMH grants MH47588 and MH62169.

References

- 1.McGlashan TH. The Chestnut Lodge follow-up study. III. Long-term outcome of borderline personalities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:20–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800010022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paris J, Brown R, Nowlis D. Long-term follow-up of borderline patients in a general hospital. Compr Psychiatry. 1987;28:530–536. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plakun EM, Burkhardt PE, Muller JP. 14-year follow-up of borderline and schizotypal personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26:448–455. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(85)90081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone MH. The Fate of Borderline Patients. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luborsky L. Clinician's judgements of mental health: a proposed scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1962;7:407–417. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1962.01720060019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The Global Assessment Scale: A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. The McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD): overview and implications of the first six years of prospective follow-up. J Pers Disord. 2005;19:505–523. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Bender DS, Grilo CM, Zanarini MC, Yen S, Pagano ME, Stout RL. Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS): overview and implications. J Pers Disord. 2005;19:487–504. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.5.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Hennen J, Silk KR. Psychosocial functioning of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. J Pers Disord. 2005;19:19–29. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.1.19.62178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skodol AE, Pagano ME, Bender DS, Shea MT, Gunderson JG, Yen S, Stout RL, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH. Stability of functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder over two years. Psychol Med. 2005;35:443–451. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400354x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanarini MC. Background Information Schedule. Belmont, MA: McLean Hospital; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: history, rational, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: discriminating BPD from other Axis II disorders. J Pers Disord. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, Gunderson JG. The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: inter-rater and test-retest reliability. Compr Psychiatry. 1987;28:467–480. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) J Pers Disord. 2002;16:270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:369–374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanarini MC, Sickel AE, Yong L, Glazer LJ. Revised Borderline Follow-up Interview. Belmont, MA: McLean Hospital; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein DN, Shankman SA, Rose S. Ten-year prospective follow-up study of the natural course of dysthymic disorder and double depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:872–880. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Shea MT, Warshaw M, Maser JD, Coryell W, Endicott J. Recovery from major depression: a 10-year prospective follow-up across multiple episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1001–1006. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanislow CA, Ansell EB, Grilo CM, Yen S, Morey LC, Little TD, Daversa M, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH. Ten-year stability and latent structure of the DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:507–519. doi: 10.1037/a0016478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, Warshaw M, Maser JD. Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1000–1006. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anthony WA, Cohen MR, Farkas MD, Gagne C. Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2nd edition. Boston, MA: Boston University, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zanarini MC, Jacoby RJ, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. The 10-year course of social security disability income reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects. J Pers Disord. 2009;23:346–356. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.4.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]