SUMMARY

The laryngocele is an abnormal saccular dilatation of the ventricle of Morgagni, which maintains its communication with the laryngeal vestibule. Three types of laryngoceles have been described: internal, external, and combined or mixed in relation to the position of the sac with respect to the thyrohyoid membrane. If the laryngocele becomes obstructed and infected it leads to the so-called laryngopyocele which, although a rare disease (8% of laryngoceles), can become an emergency causing severe airway obstruction needing urgent management, even tracheostomy. An alternative method is presented of emergency management of an internal laryngopyocele causing severe airway obstruction using a laryngeal microdebrider and avoiding tracheostomy.

KEY WORDS: Larynx, Laryngocele, Laryngopyocele, Laryngeal debrider, Airway obstruction

RIASSUNTO

Il laringocele è una anomala, sacculare dilatazione del ventricolo del Morgagni, il quale mantiene la sua comunicazione con il vestibolo laringeo. Sono stati descritti tre tipi di laringoceli: interno, esterno e combinato o misto in relazione alla posizione del sacco rispetto alla membrana tiro-ioidea. Se un laringocele si occlude e successivamente si infetta, viene chiamato laringopiocele, il quale, nonostante sia una rara malattia (8% dei laringoceli), può diventare un'emergenza determinando una severa ostruzione delle vie aeree. Spesso necessita di un trattamento d'urgenza, a volte si rende anche necessaria la tracheotomia. Presentiamo un metodo di emergenza alternativo nel trattamento di un laringiopiocele interno con ostruzione delle vie aeree, utilizzando il microdebrider laringeo ed evitando l'esecuzione della tracheotomia.

Introduction

The term laryngocele was first introduced by Virchow, in 1867 1, to describe an abnormal dilatation of the appendix of the laryngeal ventricle of Morgagni, which maintains its communication with the laryngeal lumen. It can be present at any age, but is most common in the sixth decade of life 2-4. Three types of laryngoceles have been described: internal, external, and combined or mixed in relation to the position of the sac with respect to the thyrohyoid membrane. The presenting complaint frequently includes dysphonia, dyspnoea, sore throat, globus pharyngeus, or, in severe cases, airway obstruction (presentation depends on classification, size and possible complications). If the neck of the laryngocele becomes obstructed (causes include tumours and chronic inflammation of the larynx), the mucus produced by the mucous glands of the lining epithelium, can accumulate leading to a laryngomucocele or cystic laryngocele (virtually indistinguishable from a saccular cyst). The mucocele can secondarily become infected and it is thought that 8% do at some time 5.

The treatment of a laryngocele is only indicated if it is symptomatic or has developed into a laryngomucocele or laryngopyocele. Various methods have been described including complete excision of the lesion by external / endoscopic / or a combined approach. Instrumentation has included cold steel and more recently the Carbon Dioxide (CO2) laser resection or marsupialisation 3 4 6

A case is described here of a laryngopyocele presenting with severe airway obstruction treated as an emergency by endoscopic marsupialisation with a laryngeal microdebrider avoiding tracheostomy, to our knowledge a novel application of this instrument. The procedure was straightforward, with minimal bleeding, optimal intra-operative control of the lesion and haemostasis with prompt post-operative recovery.

Case report

A 66-year-old female presented to our department as an emergency case with a one-day history of dyspnoea and dysphagia, and a few hours of stridor. Prior to this presentation, the patient had ceased smoking for one month, having previously smoked 20 cigarettes a day, for more than 20 years. She developed a cough one week after having stopped smoking, and became hoarse following a coughing fit. Progression of her symptoms included a one-week history of right neck swelling and odynophagia, with 24 hours of dyspnoea. On presentation, the patient was stridulous and pyrexial, with an oedematous swelling over levels II and III on the right hand side of the neck. An oral examination was normal, but fibreoptic nasopharyngolaryngoscopy revealed a well circumscribed erythematous swelling of the whole hemilarynx and pyriform sinus with intact mucosa, severely obstructing her airway (Fig. 1). Initial management with intravenous steroids (dexamethasone 4 mg, 3 times daily), adrenaline nebulisers (1:5000) and intravenous broad spectrum antibiotics (cefuroxime 1.5 g, 3 times daily, metronidazole 500 mg, 3 times daily) had little effect on the patient clinically, and she became progressively exhausted with increased respiratory effort.

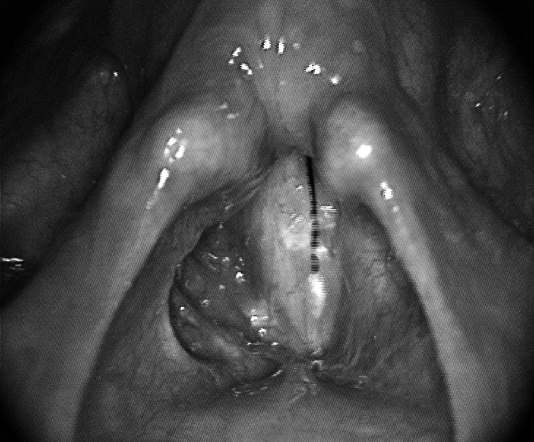

Fig. 1.

Intra-operative view of erythematous swelling of right false vocal cord.

Although the definitive diagnosis was unclear, because a computerised tomography (CT) scan was not requested due to the unsecured and deteriorating airway, the patient was taken urgently to the operating theatre to attempt to secure her airway. A tracheostomy was considered a possible option. However, with the significant risk that there might be an underlying ventricular malignancy leading to a possible future peristomal recurrence 7 8, experienced anaesthetic and otorhinolaryngology consultants awaited her with the intention of performing an awake fibreoptic nasal examination and possible intubation. Flexible endoscopy was performed after nasal anaesthesia (with 10% cocaine paste) and 6 ml of 4% lidocaine was instilled under direct vision into the pharynx, larynx and trachea. A size 5 microlaryngeal tube was rail-roaded over the scope and the patient was placed under general anaesthesia.

Surgical technique

An intra-operative workup with 0-45 degree scopes (Storz, Tutlingen, Germany) was performed along with palpation of the hemi-larynx showing a tender but fluctuating submucosal swelling. In order to confirm the fluid content of the lesion, a spinal needle connected to a 10 ml syringe was used to aspirate some contents of the sac. The purulent component was confirmed and part of the pus was sent for microbiologic assessment.

The CO2 laser was not immediately available in the emergency theatre so the surgeon opted to use a microdebrider [XPS 3000-Powered ENT System-Straightshot Magnum II Medtronic (Xomed, Minneapolis, USA) microdebrider (27.5 cm) with Tricut™ angle-tip 4 mm blade (Jacksonville, FL, USA)]. The lesion was extensively marsupialised with the debrider under endoscopic view (Fig. 2) and multiple biopsies performed. Biopsies were sent for histological evaluation from the abscess cavity and medial wall of the false vocal cord. At the end of the procedure, with a patent airway, the endo-tracheal tube was changed to a size seven and the patient was kept sedated and ventilated in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for 28 hours with continued steroid and antibiotics. At this point, the patient had a repeat microlaryngoscopy, followed by successful extubation and subsequent discharge.

Fig. 2.

Cavity following marsupialisation with the laryngeal microdebrider is clearly visible.

The histology results from the initial procedure revealed mildly inflamed fibrous connective tissue containing a few benign respiratory-type glands. However, the false vocal cord mucosa showed nuclear atypia with increased mitotic activity consistent with carcinoma in situ, with no stromal invasion.

On review, in the outpatient clinic, four weeks post-operatively, the mucosa was already well-healed, with no granulation tissue (Figs. 3, 4). Although clinical examination did not reveal any remaining lesions involving the false vocal cord, a completion CO2 laser ventriculotomy was subsequently performed in view of the presence of the carcinoma in situ. The histopathology results confirmed that the patient was free of tumour. Close follow-up is planned.

Fig. 3.

4 weeks post-operatively on adduction.

Fig. 4.

6 weeks after primary surgery at microlaryngoscopy.

Discussion

A laryngocele is an abnormal saccular dilatation of the appendix of the laryngeal ventricle of Morgagni, which maintains its communication with the laryngeal lumen. It is much more frequent in men than in women, having been described in the literature as between 5 to 7 times more frequent in males 2-4. The condition usually presents in the sixth decade of life 2-4. Unilateral presentation is more common than bilateral 2-4. It is an unusual clinical entity and the majority of laryngoceles are diagnosed incidentally 1. There have been several hypotheses regarding the aetiology of laryngoceles. Some suggest that they are atavistic remnants from apes 5, others that one has a congenital predisposition (eg. congenital long saccule) and that they are augmented by factors which increase intralaryngeal pressure, such as coughing (e.g. emphysema and/or chronic bronchitis patients) 9 10, straining, singing, playing wind instruments and glass blowing 11 12. Three types of laryngoceles have been described: internal, external and combined or mixed laryngocele 13 which refer to the anatomical extension of the sac. The internal laryngocele is confined to the paraglottic space, medial to the thyroid cartilage and thyro-hyoid membrane. The external laryngocele is a type of laryngocele which extends and dissects superiorly through the thyrohyoid membrane. It is intimately associated with the superior laryngeal nerve. A combined or mixed laryngocele includes both internal and external components of the laryngocele.

In our case, the laryngocele was limited to the paraglottic space and we can postulate that the coughing experienced by our patient, upon cessation of smoking, was likely the causative degenerative factor in this case. Furthermore, the presence of a carcinoma in situ in the false vocal cord, as seen in this patient, could be considered as the obstructive factor responsible for retention of the fluid.

Laryngoceles may be associated with laryngeal malignancies, and supra-glottic laryngeal tumours are the most common 1-14, as in our case. The incidence, described in the literature, of laryngoceles in patients with laryngeal carcinoma is variable. Micheau et al. found 18% of laryngoceles in 546 larynx specimens after total laryngectomy 15; Celin et al. reported an incidence of laryngoceles concurrent with squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx: 4.9% to 28.8% 16.

The symptoms depend upon the type and size of the laryngocele. In the majority of cases, a laryngocele is asymptomatic and produces symptoms only as it enlarges or when it becomes infected 17. The internal laryngocele often presents as a soft, more or less spherical sac of the mucosa arising from the ventricle or extending into the supraglottic region and gives subjective symptoms such as dysphonia, dyspnoea, sore throat and globus pharyngeous with associated discomfort in the neck 3 4 18. It can, rarely, cause airway obstruction which requires emergency treatment 3 9 19 20. Normally, the external laryngocele is asymptomatic, but it presents as a lateral neck mass which is either ovoid or round and is, typically, soft, elastic, mobile, conducts vibration during phonation, is painless and covered by normal skin. It increases in size during the Valsalva manoeuvre and is reducible. The mixed laryngocele presents symptoms and signs of both entities 10-18. When the connection between the laryngocele and the laryngeal lumen becomes occluded, as a result of inflammation, infection, and tumours, mucus can accumulate and a mucocele develop. A secondarily infected mucocele is called a laryngopyocele and it is thought that 8% do so at some time 5.

A CT scan of the neck is the most important examination for correct diagnosis, moreover it permits an evaluation of the relationship between the laryngeal structures and the laryngocele 21. The CT scan may show the simultaneous presence of other laryngeal lesions that are often associated with a laryngocele 22, in particular laryngeal carcinomas 1 14 17 23. In our case, as a result of the severity of airway involvement, imaging was not possible before transfer to the theatre, so a vestibular carcinoma could not be excluded.

The management of a laryngocele, when symptomatic, is complete excision or marsupialisation that can be performed by endoscopic and/or external or combined approach. The choice of the approach depends on the type and size of the laryngocele. In cases of large or external laryngocele, an external approach is indicated and several techniques have been described 24 25; while the endoscopic approach with CO2 laser is currently the preferred method of treatment for an internal laryngocele 4. Treatment of the mixed laryngocele is still controversial, several authors prefer an external approach 4-10, but a combined approach 26 and fully internal 3 approach have been championed.

Endoscopic management of the laryngocele with the use of thes CO2 laser is increasing in popularity due to the advantage of a short hospital stay, good haemostasis and avoidance of an external scar 3 4 6. However, theatre specispecification requirements, limited equipment due to costs, and necessary staff training, for laser surgery, means that it may not always be rapidly available. In our case, we used the laryngeal micro-debrider as an alternative, readily available method to classical cold steel and laser.

This device was adapted from arthoscopic equipment to aid the removal of bony and soft tissue. In the field of Otolaryngology, it was used for the first time, in 1992 27, for endoscopic sinus surgery initially by using the arthroscopic debriders. With the success and dissemination of endoscopic sinus surgery, debrider equipment is commonly available, which can be readily converted for the treatment of laryngeal pathology with the use of additional blades. They are often used for laryngeal papillomatosis and laryngeal tumour debulking 28-30, as in our Department. Given the association of malignancy with laryngoceles, all the tissue removed, by the debrider, can be easily collected, in a distal net, and sent for histological examination [Bard® Mucous Specimen Trap 40 cc (C.R. Bard, Inc. Covington, GA, USA)], or multiple biopsies performed.

Our patient had an uneventful outcome with fast, complete, epithelialisation and no granulation tissue, which is occasionally observed, after laser resection. A common preference often expressed for laser treatment is the associated improved haemostasis, but we only had minimal bleeding which was adequately controlled with topical adrenaline (1:5000 on neuropatties).

Conclusions

The Authors present a case of acute airway obstruction, caused by an internal laryngopyocele, successfully treated endoscopically with a laryngeal microdebrider, avoiding tracheostomy. As this equipment may be more readily available particularly in peripheral hospitals, it is a viable alternative to laser excision for marsupialisation of laryngoceles.

Research Integrity

Patient's consent was obtained. The Authors state they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Akbas Y, Unal M, Pata YS. Asymptomatic bilateral mixedtype laryngocele and laryngeal carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolarygol. 2004;261:307–309. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingrams D, Hein D, Marks N. Laryngocele: an anatomical variant. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:675–677. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100144822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez Devesa P, Ghufoor K, Lloyd S, et al. Endoscopic CO2 laser management of laryngocele. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1426–1430. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dursun G, Ozgursoy OB, Beton S, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment of laryngocele in adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stell MP, Maran AG. Laryngocele. J Laryngol Otol. 1975;89:915–924. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100081196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szwarc BJ, Kashima HK. Endoscopic management of a combined laryngocele. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:556–559. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breneman JC, Bradshaw A, Gluckman J, et al. Prevention of stomal recurrence in patients requiring emergency tracheostomy for advanced laryngeal and pharyngeal tumours. Cancer. 1988;62:802–805. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880815)62:4<802::aid-cncr2820620427>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leòn X, Quer M, Burgues J, et al. Prevention of stomal recurrence. Head & Neck. 1996;18:54–59. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199601/02)18:1<54::AID-HED7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pennings RJE, Hoogen FJA, Marres HAM. Giant laryngoceles: a cause of upper airway obstruction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258:37–40. doi: 10.1007/s004050100316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lancella A, Abbate G, Dosdegani R. Mixed laryngocele: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2007;27:255–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babb MJ, Rasgon BM, Calif O. Quiz Case 2: bilateral laryngocele. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:551–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isaacson G, Sataloff RT. Bilateral laryngoceles in young trumpet player: case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2000;79:272–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holinger LD, Barnes DR, Smid LJ, et al. Laryngocele and saccular cysts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1978;87:675–685. doi: 10.1177/000348947808700513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harney M, Patil N, Walsh R, et al. Laryngocele and squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:590–592. doi: 10.1258/0022215011908333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Micheau C, Luboinski B, Lanchi P, et al. Relationship between laryngoceles and laryngeal carcinomas. Laryngoscope. 1978;88:680–688. doi: 10.1002/lary.1978.88.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Celin SE, Johnson J, Curtin H, et al. The association of laryngocele with squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:529–536. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199105000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassano L, Lombardo P, Marchese Ragona R, et al. Laryngopyocele: three new clinical cases and review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257:507–511. doi: 10.1007/s004050000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verret DJ, DeFatta R, Sinard R. Combined laryngocele. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:594–596. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fredrickson KL, D'Angelo A. Internal laryngopyocele presenting as acute airway obstruction. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007;86:104–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felix JA, Felix F, Pires de Mello LF. Laryngocele: a cause of upper airway obstruction. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2008;74:143–146. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nazaroglu H, Ozates M, Uyar A, et al. Laryngopyocele: signs on computer tomography. Eur J Radiol. 2000;33:63–65. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(99)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aydin O, Ustundag E, Iseri M, et al. Laryngeal amyloidosis with laryngocele. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:361–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harvey RT, Ibrahim H, Yousem D, et al. Radiologic findings in a carcinoma associated laryngocele. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105:405–408. doi: 10.1177/000348949610500514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomé R, Thomé DC, Cortina RAC. Lateral thyrotomy approach on the paraglottic space for laryngocele resection. Laryngoscope. 2000;10:447–450. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200003000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myssiorek D, Madnani D, Delacure MD. The external approach for submucosal lesions of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:370–373. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.118690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ettema SL, Carothers DG, Hoffman HT. Laryngocele resection by combined external and endoscopic laser approach. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:361–364. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson BJ, DiBiase PA, D'Amico F. Quantitative analysis of microdebriders used in endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20:294–297. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(99)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myer CM, Willging JP, McMurray S, et al. Use of a laryngeal micro resector system. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1165–1166. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199907000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Bitar M, Zalzal GH. Powered instrumentation in the treatment of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:425–428. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simoni P, Peters G, Magnuson JS, Carroll WR. Use of the endoscopic microdebrider in the management of airway obstruction from laryngotracheal carcinoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:11–13. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]