SUMMARY

A case of subcutaneous sarcoidosis involving the paralateral nasal region is described and a brief review of the literature is made. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic disease is a rare entity and has seldom been reported on the trunk and face. Diagnosis is always difficult as it can only be confirmed by histological studies.

KEY WORDS: Head & neck, Paralateral nasal region, Subcutaneous sarcoidosis

RIASSUNTO

In questo articolo viene descritto un raro caso di sarcoidosi sottocutanea con coinvolgimento della regione paralatero-nasale e viene presentata una revisione della letteratura sull'argomento. La sarcoidosi sottocutanea senza interessamento sistemico è una patologia inusuale, e ancor più raramente è riportato il coinvolgimento del distretto cervico-facciale. La diagnosi di tale affezione può essere difficoltosa: necessita sempre della conferma istologica.

Introduction

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis is a rare cutaneous expression of systemic sarcoidosis 1.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder characterized by the formation of non-caseating granulomas. It is reported to be caused by an oligoclonal response of CD4-positive T cells to an unknown antigen 2. The disorder may be manifested in numerous ways. In 90% of the patients, intra-thoracic involvement is revealed on chest radiography. Other frequently involved sites are the reticulo-endothelial system, the skin, and the eye. Sarcoidosis can also affect joints, muscles, exocrine and endocrine glands, the heart, the central nervous system, the upper respiratory tract, and the kidney 2.

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis is characterized by non-infectious sarcoidal or epithelioid granulomas with minimal lymphocytic inflammation involving predominantly the panniculus. Subcutaneous involvement, over the extremities, occurs primarily in 20-35% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis, but may also occur without systemic disease. Histological assessment is mandatory for a definitive diagnosis 3.

The rare case of subcutaneous sarcoidosis with paralateral nasal involvement is presented.

Case report

A 38-year-old female was addressed to the ENT Department of the University Hospital of Ferrara for the assessment of a subcutaneous right paralateral nasal mass, also involving the suborbital region.

The patient had been complaining of a swelling in her right paralateral nasal region, associated with recurrent frontal headache, for 3 months. She had already been treated with systemic steroids (prednisone 25 mg/die for 3 weeks) and antibiotics (ciprofloxacin 500 mg/die for 10 days), which were unsuccessfull. Computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the paranasal sinuses were performed (Fig. 1), disclosing a subcutaneous mass, about 1 cm in diameter, at the inferior edge of the right nasal bone.

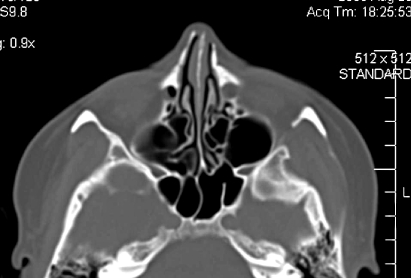

Fig. 1.

The paranasal sinuses CT (a) and MRI (b) scans revealed a subcutaneous mass about 1 cm in diameter, located at the inferior edge of the right nasal bone. Right nasal bone erosion can be detected at CT.

Her past medical history revealed histological diagnosis of erythema nodosum (EN) (right leg), when she was aged 21 years. She underwent an open septo/rhinoplasty when she was 33 (in another hospital).

At the examination, the lesion appeared nodular, non-tender, firm and painful, in the right paralateral nasal region. Serological testing for syphilis, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmatic antibodies, and antinuclear antibodies all resulted negative. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) was mildly elevated (85 nmol/ml; reference: 23-67 nmol/ ml). No other cutaneous or extra-cutaneous lesions were present and/or documented, in particular, chest X-ray and pulmonary CT scans were normal. Fundoscopy also revealed no abnormalities.

A fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was promptly performed, but the cytological result was not conclusive (documented "aspecific cells"). The mass was then excised under general anaesthesia through a paralatero-nasal approach. Upon reaching the subperiosteal plane, the lesion was gradually isolated, as the presence of a pseudocapsule facilitated the separation of the mass from the surrounding tissue. The mass was then removed.

The histological analysis indicated sarcoidosis; it revealed a nodular inflammatory mass limited to the subcutaneous tissue, composed of epithelioid granulomas, few giant cells and hyalinosis. Stains and cultures for mycobacteria and fungi were negative (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

In the specimen epithelioid cells together with multinucleate giant cells are visible. There are no signs of necrosis or of lymphocyte infiltration (H&E, x250).

The patient was addressed to the Rheumatology Unit where she was treated with prednisone 12.5 mg/die and this treatment has been maintained till now. After 30 months' of follow-up, no signs of local recurrence have been observed (Fig. 3) and, so far, no other localizations of disease have been reported.

Fig. 3.

At CT scan performed after 30 months of follow-up, no sign of local recurrence has been observed, while the profile of the right nasal bone is almost normal.

Discussion and conclusions

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease defined by the formation of non-caseating granulomas in various organs. The diagnosis is well established when clinical and radiological findings are supported by histological evidence of non-caseating granulomas in one or more tissues 4. Subcutaneous involvement occurs in 20-35% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis but may also occur alone without systemic disease 1. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis alone is defined as a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis 1. Darier and Roussy reported the first case of subcutaneous sarcoidosis in 1904 5. Vainsencher and Winkelmann, in 1984, reported 4 cases of subcutaneous sarcoidosis, 3 of which showed systemic involvement 1. It is reported to occur mainly in women, most often in their fifth or sixth decades 6.

The diagnosis of subcutaneous sarcoidosis is difficult to achieve and can only be confirmed by histological studies. Various non-specific laboratory abnormalities may be seen, such as an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and hyper-gamma-globulinaemia 2. An elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level is reported to have a sensitivity of 40-90% and a positive predictive value of up to 90% but may be falsely positive in several other granulomatous diseases, hyperthyroidism, liver cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, and Gaucher's disease. Furthermore, it may be falsely negative when ACE inhibitors are used 2 7. Other reported laboratory abnormalities include hypercalcaemia and hypercalciuria (2-63%) 2. A specific diagnostic test is the Kveim-Siltzbach skin test that has a reported sensitivity of 30-96% and is not widely used 2. The histological assessment is mandatory for a definitive diagnosis 3, as in the case presented here.

The association between subcutaneous sarcoidosis and EN, as in this case, is not frequently reported and some Authors describe the occurrence of EN as a first manifestation of immunologic disease 8-10.

Moreover, the present case report illustrates a rare localization of subcutaneous sarcoidosis, as the nodules are mainly distributed over the extremities (upper extremities, mainly in the forearms, and usually are bilateral and asymmetric) and rarely on the trunk and face 8 11.

Differential diagnosis includes lipoma, lupus vulgaris, leprosy, rosacea, granuloma, reaction to foreign bodies 9 12.

At present, there is no curative treatment for sarcoidosis. Immunosuppressive and/or immunomodulatory drugs, however, are used for controlling the disease, with corticosteroids remaining the mainstay of treatment. They function by suppressing the pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that are involved in cell-mediated immune responses and granuloma formation. Methotrexate or hydroxychloroquine may be added, especially if the response to steroids is inadequate. Although the chemokine and cytokine pathways that regulate granuloma formation are not well understood, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) is implicated. TNFα antagonists such as pentoxifylline and thalidomide are reported to be useful in refractory systemic disease and neurosarcoidosis. Infliximab (a monoclonal antibody against TNFα) in particular has a growing body of literature supporting its effectiveness, and appears to be a safe treatment approach with a good steroid-sparing effect 13 14.

In the case reported here, the paralateral nasal nodule was the only one that occurred, and the long-term treatment with steroids seems to be effective in controlling the disease.

References

- 1.Vainsencher D, Winkelmann RK. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1028–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer MP, Brouwer PA, Smit VT, et al. The challenges of extrapulmonary presentations of sarcoidosis: A case report and review of diagnostic strategies. Eur J Int Med. 2007;18:152–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerner M, Ziv M, Abu-Raya F, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis with neurological involvement: an unusual combination. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:428–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/ WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:149–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darier J, Roussy G. Des sarcoïdes sous-cutanées. Contribution à l'étude des tuberculides ou tuberculoses attenuées de l'hypoderme. Ann Dermatol Syphilol. 1904;5:144–149. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins EM, Salisbury JR, Vivier AWP. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:65–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costabel U, Teschle H. Biochemical changes in sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 1997;18:827–842. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcoval J, Mana J, Moreno A, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Br J Derm. 2005;153:790–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcoval J, Moreno A, Mana J, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:553–556. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajoriya N, Wotton CJ, Yeates DG, et al. Immune-mediated and chronic inflammatory disease in people with sarcoidosis: disease associations in a large UK database. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:233–237. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.067769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalb RF, Epstein W, Grossman ME. Sarcoidosis with subcutaneous nodules. Am J Med. 1988;85:731–736. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs HA, Tanner SB. Granulomatous disorders of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17:23–27. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32831b9e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callejas-Rubio JL, López-Pérez L, Ortego-Centeno N. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor treatment for sarcoidosis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:1305–1313. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sweiss NJ, Curran J, Baughman RP. Sarcoidosis, role of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and other biologic agents, past, present, and future concepts. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]