Abstract

Deregulation of apoptosis is a common occurrence in cancer, for which emerging oncology therapeutic agents designed to engage this pathway are undergoing clinical trials. With the aim of uncovering strategies to activate apoptosis in cancer cells, we used a pooled shRNA screen to interrogate death receptor signaling. This screening approach identified 16 genes that modulate the sensitivity to ligand induced apoptosis, with several genes exhibiting frequent overexpression and/or copy number gain in cancer. Interestingly, two of the top hits, EDD1 and GRHL2, are found 50 kb apart on chromosome 8q22, a region that is frequently amplified in many cancers. By using a series of silencing and overexpression studies, we show that EDD1 and GRHL2 suppress death-receptor expression, and that EDD1 expression is elevated in breast, pancreas, and lung cancer cell lines resistant to death receptor-mediated apoptosis. Supporting the relevance of EDD1 and GRHL2 as therapeutic candidates to engage apoptosis in cancer cells, silencing the expression of either gene sensitizes 8q22-amplified breast cancer cell lines to death receptor induced apoptosis. Our findings highlight a mechanism by which cancer cells may evade apoptosis, and therefore provide insight in the search for new targets and functional biomarkers for this pathway.

Apoptosis is a critical mechanism that allows multicellular organisms to maintain tissue integrity and function by eliminating damaged or unwanted cells. Not surprisingly, dysregulation of apoptosis has been recognized for some time as a key process in cancer development and progression (1). In light of this understanding, the positive and negative signaling events leading to apoptosis have been highly studied. These studies have led to ongoing clinical trials seeking to stimulate apoptosis in cancer cells, either by activating proapoptotic receptors or blocking the activity of downstream inhibitors (2, 3). Despite the knowledge that has been gained in recent years, there is a need to better define the mechanisms preventing apoptosis in diseases like cancer.

Activation of apoptosis via cell surface receptors is commonly referred to as the extrinsic signaling pathway. The initiation of apoptosis via this route occurs through ligand binding at the cell surface to an aptly named family of “death receptors.” Upon binding the appropriate ligand (FASL to FAS/CD95 or APO2L/TRAIL to DR4 or DR5), the death receptors engage the signaling cascade by promoting the assembly of the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). After DISC assembly, apoptosis quickly follows with the rapid activation of caspases (CASP8, CASP3, and CASP7) (4–6). Likely because of the importance and severity of apoptosis, multiple layers of regulation are known to exist. For example, negative pathway regulators include soluble and membrane-bound decoy receptors, as well as c-FLIP, a protein that competes with CASP8 during DISC assembly (3). In addition, posttranslational modifications such as palmitoylation, glycosylation, and ubiquitination (7–9), as well as transcriptional regulation (10, 11), have all been shown to modulate death receptor-mediated apoptosis. Despite the multiple layers of regulation, cancer cells are frequently found to evade clearance by apoptosis. Although this is frequently achieved indirectly through inactivation of TP53, the best example for direct inhibition of apoptosis by cancer cells is the amplification of BCL-2, a negative regulator of the intrinsic mitochondrial-derived apoptosis signaling pathway (2, 12). The importance of BCL-2 activity in promoting evasion of apoptosis by cancer cells has been well established in preclinical tumor models and has supported the initiation of clinical trials focused on blocking the activity or expression of BCL-2 in certain cancers (2). Although not as frequent, direct impairment of death receptor dependent apoptosis via mutations and down-regulation of DISC components has also been observed (13, 14).

To identify regulators of death receptor-induced apoptosis, we performed a genome-wide RNAi screen by using the pooled-shRNA approach described previously by others (15–17). This approach led to the identification of 16 hits whose knockdown increases the sensitivity of cells to FASL. Two of these genes, EDD1 and GRHL2, localize to a 50-kb region on chromosome 8q22 that is amplified and overexpressed in multiple tumor types. In-depth mechanistic studies demonstrated that both EDD1 and GRHL2 negatively regulate death receptor (FAS and DR5) expression. These observations suggest that amplification of the 8q22 region provides a mechanism by which cancer cells may evade death receptor-activated therapies. In agreement with this conclusion, EDD1 expression is elevated in breast, pancreas, and lung cancer cell lines resistant to death receptor-mediated apoptosis. Furthermore, silencing the expression of either EDD1 or GRHL2 sensitizes 8q22-amplified breast cancer cells to ligand induced apoptosis. Together these findings describe a mechanism for regulating apoptosis and highlight potential therapeutic strategies for activating apoptosis in cancer.

Results

Whole-Genome RNAi Screen for Regulators of Death Receptor-Mediated Apoptosis.

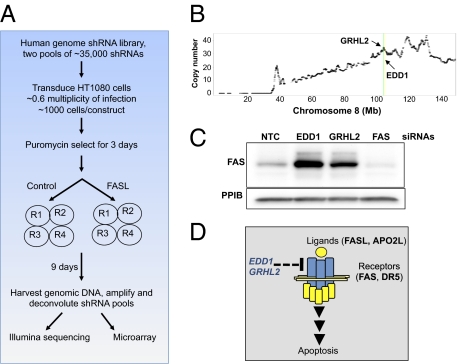

To identify regulators of death receptor-induced apoptosis, we performed a genome-wide pooled-shRNA screen by using a previously described lentiviral shRNA library (16). As outlined in Materials and Methods, the screen was initiated by dividing the library into two viral pools, with each pool consisting of approximately 35,000 shRNAs. Each shRNA pool was applied in parallel onto the fibrosarcoma HT1080 cell line. The cells were challenged twice over the span of 9 d with FAS ligand (FASL) at 150 ng/mL, a concentration that is between the 20% inhibitory concentration (IC20) and IC50 of FASL for these cells. After recovering the integrated shRNAs by PCR, the change in shRNA representation between the FASL-treated and control cells was quantified through the use of custom microarrays as well as Illumina sequencing. We chose both methods for pool deconvolution to help overcome the biases that are likely inherent within each technique.

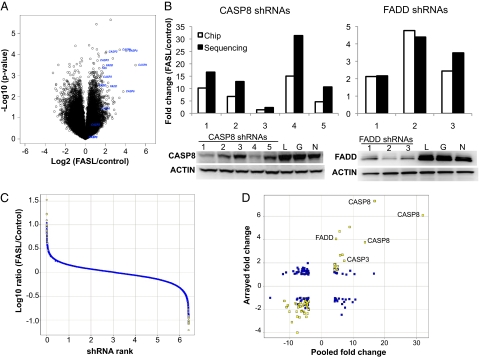

To rank order hits, the deconvoluted data were first analyzed by calculating a ratio between the control and FASL-treated arms. As shown in Fig. 1A, several independent shRNAs targeting known regulators of apoptosis displayed an expected outlier profile, including those targeting FAS, FADD, CASP8, and CASP3. Importantly, the phenotypic response quantified by the custom microarrays or sequencing matched the silencing efficacy for a given shRNA (Fig. 1B). Together these observations suggested our screening and analysis methods were sufficiently robust to analyze the entire data set for novel apoptosis regulators. We selected the top depleted and enriched shRNAs by using the criteria described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1C). This thresholding identified a total of 247 shRNAs; 152 shRNAs selected by Illumina sequencing and 122 shRNAs selected by microarray. Of this total, 27 shRNAs were shared as top-ranked hits between the two deconvolution methods.

Fig. 1.

Data quality, hit selection, and validation. Enrichment of shRNAs targeting known positive regulators of FAS-dependent apoptosis. (A) Representative pool deconvolution data derived from Illumina sequencing comparing the log2 ratio of FASL-treated vs. control samples relative to the log10-converted P value calculated for each shRNA. The shRNAs targeting CASP3, CASP8, FAS, and FADD are highlighted. (B) The enrichment of shRNAs targeting CASP8 and FADD as determined by sequencing or array based deconvolution (Top) correlates with the degree of silencing for both genes (Bottom, Western blots; numbers represent CASP8 or FADD shRNAs; L, G, and N represent control shRNAs targeting luciferase, GAPDH, or a scrambled sequence, respectively). The P value for both FADD and CASP8 shRNA enrichment was lower than 0.005 for all shRNAs shown except CASP8 shRNA 3. (C) Hit selection criteria consisted of threefold change plus a P value < 0.02 for the array data and a fourfold change plus a P value lower than 0.02 for sequencing data. A representative figure highlighting the hits selected from the sequencing data is shown. (D) Comparison of the primary pooled shRNA data with a follow-up secondary assay using individual shRNAs. The top hits from the primary screen were tested in an arrayed 96-well format as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown are represented as fold change (FASL/control) comparing the individually arrayed shRNAs (“Arrayed”) vs. the selected shRNA's performance in the primary screen (“Pooled”). Highlighted in yellow are shRNAs that met the arrayed validation threshold (P < 0.05 and fold change >1.5); the fold change and P values for these hits are listed in Dataset S1.

Validation of Top Enriched and Depleted shRNAs.

To validate the top primary screen hits, we infected HT1080 cells with the appropriate shRNA and quantified the impact on viability 72 h after FASL treatment. Although the dynamic range of this secondary assay was reduced relative to the original primary data (Fig. 1D), we were again able to identify shRNAs targeting known modulators such as FADD, CASP8, and CASP3. By using the positive control shRNAs as a guide, we set a threshold for hit validation from the secondary assay using the criteria described in Materials and Methods. With this validation criteria, 111 of the 247 original hits retested positive, resulting in an approximate 42% validation rate for both deconvolution datasets (Dataset S1).

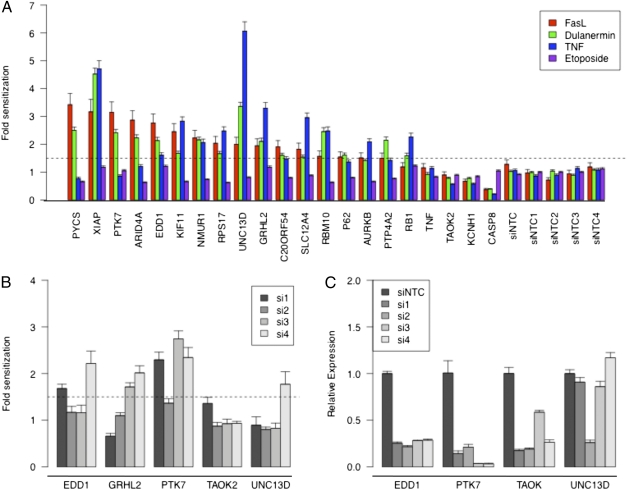

To begin removing shRNA hits that were a result of an off-target RNAi effect, we repeated the FASL challenge by silencing the target genes by using siRNAs pools whose sequences differed from the original shRNA. With these experiments, we focused solely on the gene targets for the top depleted shRNAs, as this class of hits may provide insight into novel, therapeutically relevant, negative regulators of apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 2A and Dataset S1, silencing 16 of the top depleted hits continued to cause at least a 1.5-fold sensitization to FASL with a P value lower than 0.001. We next sought to delineate the specificity of these hits for FASL-dependent apoptosis. For this purpose, we performed the same siRNA-based silencing experiment described earlier and tested the resulting sensitivity to additional death receptor ligands dulanermin (a DR4/DR5-specific agonist) and TNF, as well as etoposide, a topoisomerase II inhibitor that causes apoptosis through DNA damage (18). As shown in Fig. 2A, none of the hits impacted sensitization to etoposide, suggesting the observed sensitization to FASL is not simply a result of a nonspecific decrease in cellular health. In contrast, most of the screening hits sensitized cells to all three death receptor ligands. Only three genes (PYCS, PTK7, ARID4A) displayed a partial selectivity for FASL and dulanermin over TNF-mediated apoptosis. The lack of selectivity for a specific death receptor ligand is not surprising as a result of the high degree of signaling overlap within the extrinsic apoptosis pathways. Together, these results support the conclusion that our screening design was successful at identifying negative regulators of ligand-induced apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Validation of top depleted primary hits using siRNAs. (A) The top depleted hits from the primary and secondary screen were validated with a tertiary assay by using siRNA pools as described in Materials and Methods. After transfection with the indicated siRNA, cells were treated with FASL, dulanermin, TNF, or etoposide, and the impact on cell viability quantified with Cell-Titer Glo. A representative experiment is shown in which each sample was performed in replicates of six. A dotted line indicates the threshold for sensitization set at 1.5 fold over controls. (B) The siRNA pools for PTK7, UNC13D, TAOK2, EDD1, and GRHL2 were deconvoluted and individually transfected into HT1080 cells. The impact on sensitivity to FASL-mediated apoptosis was determined as described earlier. A dotted line indicates the threshold for sensitization set at 1.5 fold over controls. The fold change and P values calculated for Fig. 2 A and B are listed in Dataset S1. (C) Confirmation of on-target silencing for each siRNA by using a gene-specific quantitative RT-PCR analysis 72 h after transfection. The relative expression of each gene was normalized to the expression of HPRT and is displayed relative to nontargeting control siRNA-transfected cells. A representative experiment is shown in which each sample was performed in triplicate, with the error bars representing the SD of the mean.

Identification of an 8q22 Gene Cluster That Negatively Regulates Death Receptor Expression.

Because of the frequent amplification of BCL-2, a negative regulator of the intrinsic apoptosis signaling pathway (2, 12), we inspected microarray databases to determine whether any of our top hits exhibited cancer-specific overexpression or copy number alterations. Five of the genes identified in our screen (EDD1, GRHL2, TAOK2, PTK7, and UNC13D) exhibit overexpression and/or copy number gains in at least one cancer indication (Fig. S1, Table S1, and Dataset S2). Based on this information, we chose to further validate the RNAi-mediated phenotype of these five genes. To minimize the chance that the observed results were caused by an off-target RNAi phenomenon, the impact on sensitivity to FASL was quantified by using four independent siRNAs for each gene. As shown in Fig. 2B and Dataset S1, cells were sensitized to FASL with at least two independent siRNAs upon silencing PTK7 (siRNAs 1, 3, and 4), EDD1 (siRNAs 1 and 4), and GRHL2 (siRNAs 3 and 4), a single siRNA for UNC13D (siRNA 4), and none for TAOK2. Although the siRNAs targeting PTK7 and EDD1 were effective at silencing their target gene expression (Fig. 2C), we were unable to accurately quantify the degree of on-target silencing for GRHL2 in HT1080 cells as a result of low expression levels. The ability to reproduce the phenotype with multiple independent siRNAs supports the original primary screening data in which a depletion of two independent shRNAs for PTK7, EDD1, and GRHL2 was observed (Fig. S2A). Together, these results supported ranking PTK7, EDD1, and possibly GRHL2 as the top on-target screening hits.

To better understand the mechanism of how the top ranked hits (PTK7, EDD1, and GRHL2) regulate FASL-mediated apoptosis, we examined whether these genes regulate expression of the death receptor. As shown in Fig. S2B, silencing PTK7, EDD1, or GRHL2 resulted in a corresponding two- to fourfold increase in FAS mRNA levels. Interestingly, a similar impact on DR5 mRNA levels was observed upon silencing EDD1 and GRHL2, whereas silencing PTK7 exhibited little or no effect on DR5 expression. In contrast to the induction of FAS and DR5 expression, silencing PTK7, EDD1, or GRHL2 resulted in little or no induction of a third death receptor, TNFR1 (Fig. S2B). These results demonstrate the top three screening hits all appear to modulate expression of the FAS receptor, which is a likely mechanism by which silencing PTK7, EDD1, or GRHL2 sensitizes cells to FASL. Interestingly, PTK7 exhibits the greatest specificity at regulating the FAS receptor, with EDD1 and GRHL2 regulating the expression of both FAS and DR5 receptors.

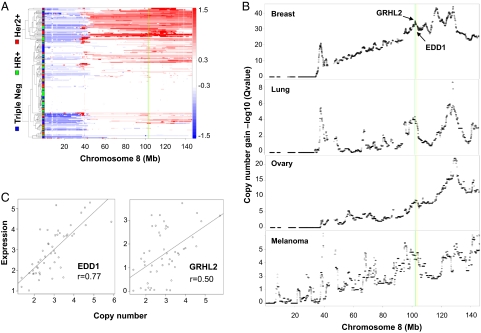

The observation that EDD1 and GRHL2 may negatively regulate not only FAS but also DR5 expression is intriguing as it increases their potential value as targets that would help to sensitize cancer cells to therapeutically relevant death receptor agonists. Therefore, we decided to focus further experimental efforts on these two genes. We began by first inspecting the genomic and expression data for EDD1 and GRHL2 in closer detail and found that both localize to a genomic region on chromosome 8q22, a region that exhibits a high frequency of copy number gains across multiple cancers (Fig. 3 and Table S1). By using the GISTIC algorithm as a method to analyze copy number changes across multiple tumor samples (19), we found that both GRHL2 and EDD1 reside within a large region of significant copy number gain on chromosome 8 within breast, lung, melanoma, and ovarian cancers (Fig. 3B). Importantly, the genomic amplification strongly correlated with the expression level for both EDD1 and GRHL2 (Fig. 3C). Based on the frequent amplification and overexpression of both genes, as well as the evidence that EDD1 and GRHL2 may regulate expression of therapeutically relevant death receptors, we decided to further validate their associated RNAi phenotypes in the hope of determining their role as negative regulatory components of FAS and DR5 mediated apoptosis.

Fig. 3.

EDD1 and GRHL2 reside within an amplicon present on chromosome 8q22. (A) A heat map of copy number for chromosome 8 in breast tumors. Tumor samples are represented as rows and grouped based on hierarchical clustering of copy number profiles. The tumor classification of triple negative, hormone receptor-positive (HR+), and HER2+ are noted on the left axis in blue, green, and red, respectively. Log2 ratios from GLAD segmentation are color-coded based on the scale shown on the right (red represents gain and blue represents loss). (B) A GISTIC analysis of chromosome 8 was performed as described in Materials and Methods across a panel of breast, lung, ovarian, and melanoma tumor samples. The locations of EDD1 and GRHL2 in A and B are highlighted with yellow and green lines, respectively. Copy number data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession no. GSE20393). (C) The expression of EDD1 and GRHL2 correlates with genomic copy number gains across a panel of breast cancer cell lines.

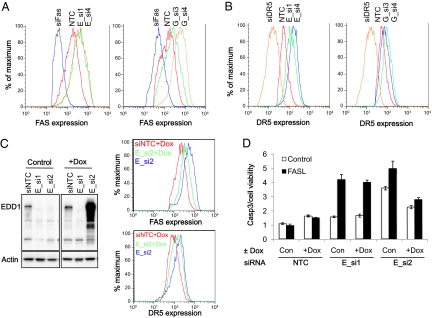

To determine whether the induction of FAS and DR5 mRNA levels corresponded with an increased cell surface expression of both receptors, FACS analyses of cells transfected with EDD1 and GRHL2 siRNAs was performed. Upon silencing either EDD1 or GRHL2, there was an induction of FAS and DR5 cell surface expression (Fig. 4 A and B), consistent with a negative regulatory role over death receptor expression. Although these phenotypic effects were reproducible with multiple, nonoverlapping RNAi reagents (Figs. 2 B and C and 4 A and B and Fig. S2), the gold standard for demonstrating the on-target nature of a given RNAi phenotype is a rescue experiment. To this end, we engineered an EDD1 cDNA to be resistant to silencing by EDD1_si2 but not EDD_si1 (Fig. 4C). Expression of the RNAi-resistant version of EDD1 rescued the phenotype associated with EDD1_si2, resulting in a decreased induction of FAS and DR5 expression (Fig. 4C), as well as sensitization to FASL-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 4D). As expected, the RNAi-resistant EDD1 had little or no ability to rescue the phenotype associated with EDD1_si1 (Fig. 4D). Unfortunately, we were unable to successfully rescue the RNAi phenotype associated with GRHL2 silencing and therefore cannot rule out the possibility that the GRHL2 silencing phenotype is not fully an on-target phenomenon. However, the ability to reproduce its associated phenotype with multiple RNAi reagents helps to reduce the concern for off-target effects.

Fig. 4.

Silencing EDD1 or GRHL2 increases cell surface FAS (A) and DR5 (B) expression in HT1080 cells. FAS and DR5 expression levels were determined 72 h after transfection with two independent siRNAs targeting the indicated gene: EDD1, E_si1 and E_si4; and GRHL2, G_si3 and G_si4. (C and D) To demonstrate the ability to rescue the RNAi knock-down of endogenous EDD1, the target sequence for a single siRNA (E_si2) was disrupted with multiple silent mutations and cloned into a viral vector enabling doxycycline-regulated expression of a FLAG-tagged EDD1 protein. A stable pool of HT1080 cells was generated and cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (Dox) to induce EDD1 expression. Three days after doxycycline addition, cells were transfected with siNTC or EDD1 siRNAs (E_si1 or E_si2). (C) Left: Western blot demonstrates resistance of the doxycycline-regulated EDD1 to silencing by E_si2 but not E_si1. Right: Effect of silencing endogenous EDD1 on FAS or DR5 expression was compared with cells expressing the RNAi-resistant EDD1 (doxycycline-treated cells) by FACS. (D) Expression of an RNAi-resistant FLAG-EDD1 rescues the enhanced sensitivity to FASL upon silencing endogenous EDD1. HT1080 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline for 3 d, followed by transfection with siNTC, E_si1 (an siRNA that silences endogenous and Flag-tagged EDD1), and E_si2 (which silences only endogenous EDD1). Three days after siRNA transfection, cells were treated with or without 150 ng/mL FASL and the level of activated CASP3/7 was quantified. The data presented in D are displayed as a ratio between CASP3/7 activity levels relative to the number of viable cells. A representative experiment is shown in which each sample was performed in triplicate, with the error bars representing SD of the mean.

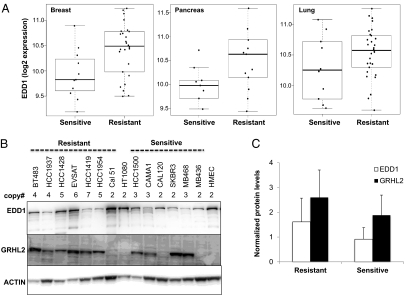

Given our functional data suggesting EDD1 and GRHL2 suppress apoptosis, we hypothesized that amplification of either gene could contribute to a mechanism by which cancer cells evade therapeutic challenge with death receptor agonists. To address this question, we interrogated a previously published gene expression profiles derived from a panel of dulanermin-sensitive and -resistant cancer cell lines (7). As shown in Fig. 5A, our hypothesis was supported by the fact that EDD1 expression is elevated in dulanermin-resistant pancreatic, breast, and lung cancer cell lines compared with sensitive cell lines. Despite the close proximity to EDD1 on chromosome 8q, we did not find a statistically significant difference in GRHL2 expression between the dulanermin-sensitive and -resistant cell lines (Fig. S3A). Furthermore, we were able to confirm EDD1 and GRHL2 protein expression in several dulanermin-resistant breast cancer cell lines exhibiting copy number gains at the 8q22 locus (Fig. 5B). Although there does not appear to be a strong correlation between protein expression and resistance to dulanermin (Fig. 5C), we cannot rule out the presence of additional mechanisms that may regulate expression of EDD1 and GRHL2. Because of the solid correlation observed between copy number and RNA expression (Fig. 3C), those additional mechanisms regulating EDD1 and GRHL2 expression are likely to be posttranscriptional.

Fig. 5.

EDD1 expression correlates with resistance of cancer cell lines to dulanermin. (A) EDD1 mRNA expression is significantly elevated in dulanermin-resistant compared with dulanermin-sensitive breast (P = 0.0097) and pancreatic (P = 0.012) cancer cell lines and is moderately elevated in lung cancer cell lines (P = 0.098). Microarray gene expression data were generated across a panel of dulanermin-sensitive and -resistant cell lines as described previously (7). Sensitivity to dulanermin was classified by using an IC50 threshold of 1 μg/mL. Cell lines with an IC50 greater than 1 μg/mL were classified as resistant, whereas those with an IC50 lower than 1 μg/mL were classified as sensitive to dulanermin. (B) Comparison of EDD1 and GRHL2 protein expression across a panel of dulanermin-resistant and -sensitive breast cancer cell lines. The copy number gain of the 8q22 amplicon is indicated above each cell line. The blots were reprobed for ACTIN as a loading control. (C) The protein expression of EDD1 and GRHL2 was quantified and normalized to ACTIN within each cell line. The expression fold change was calculated by comparison with normal human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC).

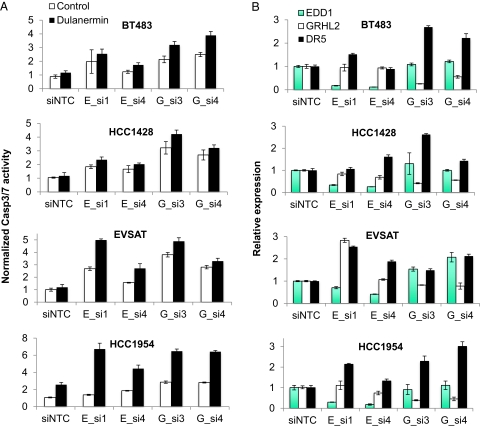

The functional relevance for the 8q22 gene cluster was tested directly by quantifying the effect of silencing EDD1 or GRHL2 in dulanermin-resistant breast cancer cell lines. As shown in Fig. 6A, silencing EDD1 or GRHL2 sensitized four 8q22-amplified breast cancer cell lines to dulanermin-induced apoptosis. Importantly, although the sensitization to dulanermin was modest in several cases, it correlated with the degree of EDD1 or GRHL2 silencing, as well as a corresponding induction of DR5 expression (Fig. 6B and Fig. S3B). Collectively, these results support the model that amplification of EDD1 and GRHL2 decreases the sensitivity of cells to apoptosis by modulating death receptor expression and therefore are targets for enhancing the activation of apoptosis in cancer cells.

Fig. 6.

EDD1 and GRHL2 expression regulate the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to dulanermin-induced apoptosis. (A) Silencing EDD1 or GRHL2 enhances dulanermin-induced apoptosis. The indicated dulanermin-resistant and 8q22-amplified breast cancer cell lines were treated with dulanermin 72 h after transfection with the siRNAs targeting the noted gene. Data are displayed as a ratio between CASP3/7 activity levels relative to the number of viable cells in the absence of dulanermin. A representative experiment is shown in which each sample was performed in triplicate, with the error bars representing SD of the mean. (B) The impact of silencing EDD1 and GRHL2 on DR5 expression correlates with the degree of sensitization to dulanermin. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed 72 h after transfection with the indicated siRNA. The relative expression of each gene was normalized to the expression of HPRT and is displayed relative to siNTC transfected cells.

Discussion

We performed a genome-wide RNAi screen by using a pooled lentiviral shRNA library (15, 16) to identify regulators of apoptosis. To help quickly remove off-target effects, we validated the ability to repeat the FASL sensitization phenotype of the top depleted hits by using siRNAs with unique target sequences. With this approach, we validated 16 genes whose silencing sensitized cells to FASL. Interestingly, although most of these hits also sensitized cells to other death receptor ligands, none sensitized cells to etoposide, a canonical trigger for the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. Because of the importance of dysregulated apoptosis in cancer, we were intrigued to find that several of the top primary screening hits exhibit copy number gains and/or overexpression in certain cancers. Surprisingly, two of these genes (EDD1 and GRHL2) are approximately 50 kb apart on chromosome 8q22 and are frequently amplified in breast cancer, lung cancer, melanoma, and ovarian cancer. Mechanistically, we have provided data showing that both genes inhibit death receptor-mediated apoptosis by repressing the expression of FAS and DR5 death receptors. Therefore, our results support a model wherein cancer cells exhibiting an amplification of 8q22 may be more resistant to death receptor-induced apoptosis and that inactivating the activity or expression of EDD1 or GRHL2 would provide a therapeutically relevant strategy to improve responsiveness to death receptor agonists. This hypothesis is supported by the correlation between elevated EDD1 expression in cancer cell lines classified as resistant to death receptor apoptosis as well as the demonstration that silencing either EDD1 or GRHL2 sensitizes breast cancer cells to ligand-induced apoptosis.

Previous reports have also described a link to cancer for both EDD1 and GRHL2. EDD1 was initially described from mutational screens in drosophila as hyperplastic discs (hyd), which, when disrupted, resulted in overgrowth of the imaginal discs (20–22). The mammalian orthologue E3 identified by Differential Display (EDD) was first discovered through the use of differential display to identify progestin-regulated genes in a breast cancer cell line (23). Evidence suggesting an involvement of EDD1 in human cancer includes the finding from several studies demonstrating that the degree by which EDD1 interacts with CIB, TOPBP1, and CHK2 is regulated by the DNA damage response (22, 24, 25). Moreover, EDD1 expression has been shown to functionally correlate with the responsiveness of patients with ovarian cancer to DNA-damaging cytotoxic therapies (26). Several reports have also demonstrated that EDD1 is overexpressed in a high percentage of cancers, consistent with a pattern that correlates with an increased copy number of the EDD1 locus (27, 28). Finally, cancer-specific somatic mutations of EDD1 have been observed; however, the functional consequence of the mutations are unknown (28, 29). As with EDD1, several studies have reported cancer-specific aberrations of GRHL2. First, GRHL2 expression has been shown to be required for telomerase activity and viability in cancer cells (30). Second, GRHL2 copy number gain has been shown to correlate with a decrease in recurrence-free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (31). The functional consequence of this was suggested through silencing GRHL2, an event that subsequently decreased hepatoma cell proliferation.

In summary, there is growing evidence that alterations at the chromosomal 8q22 region enhance the expression, and presumably activity, of EDD1 and GRHL2. Our data reported herein provide a possible mechanistic explanation for these observations by suggesting that cancer cells gain resistance to death receptor-mediated apoptosis through the altered expression of one or both genes. The exact details of this regulation remain to be defined. For example, although we were unable to detect any EDD1-dependent posttranslational modification of FAS, it is possible that EDD1 and GRHL2 regulate the expression and/or stability of a key transcriptional component(s). This scenario is consistent with the nuclear localization of both genes, as well as the fact that both EDD1 and GRHL2 have previously been linked to the transcriptional regulation of other genes (22, 30, 32, 33). Additional studies will be required to define the downstream targets that mediate the effect of EDD1 and GRHL2 on apoptosis signaling. These efforts will be valuable as they will provide insight into novel therapeutically relevant approaches to enhance selective targeting of apoptosis in cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Expression Constructs.

Cell lines included the fibrosarcoma cell line HT1080 and breast cancer cell lines BT483, EVSAT, HCC1428, HCC1419, HCC1954, HCC1937, HCC1500, Cal-120, Cama-1, Cal51, SKBR3, MB468, and MB436. Flag-tagged EDD-1 (NM_015092) and GFP-tagged GRHL2 (NM_024915) were cloned into a previously described viral vector enabling doxycycline regulated expression (34).

Generation of Pooled Virus.

A lentiviral-based library containing approximately 70,000 shRNAs directed against the human genome has been previously described (16). The DNA for each shRNA was purified and pooled at equimolar concentrations to generate 14 pools consisting of 5,000 shRNA constructs per pool. Virus was subsequently generated and tittered for each shRNA pool of 5,000, followed by combining the individual viral pools in equal amounts of viral transduction units from each pool into two large shRNA pools consisting of approximately 35,000 shRNA constructs each.

Primary shRNA Pooled Screen.

Each shRNA pool was applied in parallel onto the fibrosarcoma cell line HT1080 at a multiplicity of infection of approximately 0.6 to obtain a representation of at least 1,000 shRNAs per cell. After puromycin selection (1 μg/mL for 72 h), the cells were divided into eight replicates and cultured in the presence or absence of FASL. Four of the replicates were challenged twice over the span of 9 d with 150 ng/mL FLAG-tagged FASL plus 1 μg/mL anti-FLAG (F3165; Sigma), whereas the remaining four replicates were treated with the anti-FLAG antibody alone. Nine days after the first treatment, genomic DNA was harvested by using methods previously described (16).

PCR Amplification and Labeling of Integrated shRNAs.

The integrated vectors were PCR-amplified from purified genomic DNA (3 μg input per reaction) by using-vector specific primers. Forward primer was 5′-TAG TGA AGC CAC AGA TGT A-3′; reverse primer with T7 promoter was 5′-GTA ATA CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG GTA ATC CAG AGG TTG ATT GTT CCA GAC GC-3′. The resulting PCR product was column purified with a DNA clean-up column (28104; Qiagen). Four separate PCR reactions were generated for each replicate, column-purified, and then pooled into one reaction. The quantity of each PCR was measured by using a UV spectrophotometer (ND-1000; Thermo Scientific) and the size was confirmed by electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gels (Invitrogen). To prepare the samples for microarray-based analysis, each PCR (50 ng per reaction) was used as a template for in vitro transcription using a Low RNA Input Fluorescent Linear Amplification protocol (5184-3523; Agilent Technologies). The reference (no treatment at day 0) and test samples (FasL treatment at day 9) were labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 dyes, respectively. Dye incorporation and yield of purified, labeled cRNA was quantified with ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific). To prepare samples for Illumina sequencing, 10 ng of the PCR-amplified shRNA product described earlier was adapted with Illumina sequencing tags by using 10 cycles of a nested PCR amplification. The resulting products were gel-purified and sequenced according to manufacturer-suggested procedures (Illumina).

Microarray Hybridizations.

A custom Agilent microarray was generated based on unique 60-mer sequences previously described (16). Each oligonucleotide was printed in triplicate resulting in 244K array format. The Cy5 test and Cy3 reference probes were combined and hybridized onto the arrays. Following hybridization, the arrays were washed and scanned according to the manufacturer's protocol (Agilent Technologies). Microarray images were analyzed by using Feature Extraction software, version 9.5 (Agilent Technologies). Quality of array hybridizations and preliminary data analysis was done by using Rosetta Resolver (Rosetta Biosoftware) and Spotfire (Tibco). Data for replicate probes were averaged for each shRNA and then compared between FASL-treated vs. control samples using a two-sided t test.

Illumina Sequencing.

Sequencing reads from different samples were segregated by the unique sequence tags representing each sample. Sequencing reads from each sample were compared with the shRNA sequences by using the BLAST program. Sequencing reads were mapped to the best-matched shRNA whereby the alignment has no greater than one mismatched nucleotide over the length of at least 17 nt and E-value less than 0.01. The number of reads mapped to each library shRNA in a given sample was normalized by dividing the total number of mapped reads from this sample and multiplying by 106. The normalized counts were then log-transformed (added with 0.05 to offset “0”). For comparison of shRNA abundance in FASL-treated vs. control samples, the log-transformed counts for each sample of the two arms were normalized by subtracting the baseline value and then the resulted values were compared by using a two-sided t test.

Hit Identification.

Hits from the primary pooled shRNA screening data were selected based on the following criteria: a P value less than or equal to 0.02, plus a fold change requirement of threefold for the microarray or fourfold for the sequencing data. Hits from the secondary individually arrayed shRNA follow-up study were based on the following criteria: a P value less than or equal to 0.05 and a fold change greater than or equal to 1.5.

Hit Validations.

Secondary hit validation was performed by “cherry-picking” shRNA constructs corresponding to hits selected from the primary pooled shRNA screen. Each construct was individually arrayed in 96-well plates and used to generate virus. HT1080 cells (1.5 × 103 cells per well) were subsequently transduced to result in nine replicates per shRNA. After 72 h, the transduced cells were treated with or without FASL (150 ng/mL) and assayed for viability 48 h after FASL treatment (Cell-Titer Glo, G7570; Promega). To normalize for variations in transduction efficiencies, the number of viable cells after 72 h of puromycin selection was quantified. Tertiary hit validation was performed by using siRNA pools (Dharmacon). Three days after siRNA transfection, cells were treated with the appropriate apoptosis stimuli [150 ng/mL FASL, 50 ng/mL dulanermin, or 1 μg/mL TNF plus 2 μg/mL cycloheximide; all three ligands were cross-linked with 1 μg/mL of anti-FLAG (F3165; Sigma) or 100 μM etoposide]. The impact on viability was assayed 5 h after FASL and dulanermin or 24 h after TNF and etoposide treatments by using Cell-Titer Glo (Promega). The siRNA validation data were analyzed by using a linear regression model whereby the statistical significance of the induced change in cell viability for each siRNA was evaluated in contrast with the negative control siRNAs (siNTCs). Fold sensitization was calculated by dividing the viability fold change between treatment vs. control for each siRNA by the fold change with siNTCs. Fold sensitization and P values obtained from linear regression analyses are included in Dataset S1. The shRNA and siRNA sequences used to validated the top depleted hits are listed in Dataset S3.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Western blots were performed as described previously (35). Between 20 and 80 μg of total protein was loaded on a Tris/glycine gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane (VWR). The blots were probed by using anti-Fas (4233; Cell Signaling), anti-EDD1 (A300-573A; Bethyl), anti-FADD (556402; BD), anti-DR5 (3696; Cell Signaling), or anti-GRHL2 (H00079977-B01P; Abnova).

FACS Analysis.

FACS analysis was performed by washing cells four times in FACS buffer (2% FBS in PBS solution), followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature with the appropriate phycoerythrin-conjugated antibody and washing four times in FACS buffer. Samples were analyzed with a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Antibodies used were FAS (12-0959; eBioscience), DR5 (12-9908; eBioscience), DR4 (12-6644; eBioscience), and transferrin (12-0719; eBioscience).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

RNA was harvested from cells by using RNeasy procedures (74104; Qiagen) and then used as template in a one-step reaction with QuantiTect Probe RT PCR (204443; Qiagen). Quantitative RT-PCR reactions were performed following the manufacturer's procedures by using premade primer/probe sets (ABI), and data were generated by using an ABI 7900 system (ABI).

Expression and Copy Number Analysis.

Expression data for EDD1, GRHL2, TAOK2, PTK7, and UNC13D derived from the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 arrays were extracted from the Gene Logic expression database. Expression summary values for all probe sets were calculated by using the RMA algorithm as implemented in the Affy package from Bioconductor. Statistical analyses of differentially expressed genes were performed by using a one-sided t test. Copy number was determined from tumor samples profiled on the Agilent human CGH arrays (Gene Expression Omnibus accession no. GSE20393). All processed copy numbers were centered to a median of two and segmented by using GLAD (36). Copy number values for specific genes were calculated as the mean copy number value for the probe sets bounding the gene location and all intervening probe sets using the segmented data. Regions of significant gains were identified by using the GISTIC algorithm as described previously (37).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Luk, B. Edris, and G. Bennett for expertise in generating shRNA DNA stocks; Y. Liang and H. Chen for technical assistance at generating viral stocks; and F. de Sauvage, D. Stokoe, and A. Ashkenazi for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: All the authors are employees of Genentech.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE20393).

See Author Summary on page 17591.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1100132108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang MH, Reynolds CP. Bcl-2 inhibitors: Targeting mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1126–1132. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashkenazi A. Directing cancer cells to self-destruct with pro-apoptotic receptor agonists. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:1001–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrd2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: Signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peter ME, Krammer PH. The CD95(APO-1/Fas) DISC and beyond. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:26–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner KW, et al. Death-receptor O-glycosylation controls tumor-cell sensitivity to the proapoptotic ligand Apo2L/TRAIL. Nat Med. 2007;13:1070–1077. doi: 10.1038/nm1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feig C, Tchikov V, Schütze S, Peter ME. Palmitoylation of CD95 facilitates formation of SDS-stable receptor aggregates that initiate apoptosis signaling. EMBO J. 2007;26:221–231. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin Z, et al. Cullin3-based polyubiquitination and p62-dependent aggregation of caspase-8 mediate extrinsic apoptosis signaling. Cell. 2009;137:721–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smyth MJ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) contributes to interferon gamma-dependent natural killer cell protection from tumor metastasis. J Exp Med. 2001;193:661–670. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu GS, et al. KILLER/DR5 is a DNA damage-inducible p53-regulated death receptor gene. Nat Genet. 1997;17:141–143. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsujimoto Y, Cossman J, Jaffe E, Croce CM. Involvement of the bcl-2 gene in human follicular lymphoma. Science. 1985;228:1440–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.3874430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufmann SH, Vaux DL. Alterations in the apoptotic machinery and their potential role in anticancer drug resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7414–7430. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe SW, Cepero E, Evan G. Intrinsic tumour suppression. Nature. 2004;432:307–315. doi: 10.1038/nature03098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlabach MR, et al. Cancer proliferation gene discovery through functional genomics. Science. 2008;319:620–624. doi: 10.1126/science.1149200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva JM, et al. Profiling essential genes in human mammary cells by multiplex RNAi screening. Science. 2008;319:617–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1149185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brummelkamp TR, et al. An shRNA barcode screen provides insight into cancer cell vulnerability to MDM2 inhibitors. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:202–206. doi: 10.1038/nchembio774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karpinich NO, Tafani M, Rothman RJ, Russo MA, Farber JL. The course of etoposide-induced apoptosis from damage to DNA and p53 activation to mitochondrial release of cytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16547–16552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beroukhim R, et al. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20007–20012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin P, Martin A, Shearn A. Studies of l(3)c43hs1 a polyphasic, temperature-sensitive mutant of Drosophila melanogaster with a variety of imaginal disc defects. Dev Biol. 1977;55:213–232. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansfield E, Hersperger E, Biggs J, Shearn A. Genetic and molecular analysis of hyperplastic discs, a gene whose product is required for regulation of cell proliferation in Drosophila melanogaster imaginal discs and germ cells. Dev Biol. 1994;165:507–526. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson MJ, et al. EDD, the human hyperplastic discs protein, has a role in progesterone receptor coactivation and potential involvement in DNA damage response. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26468–26478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callaghan MJ, et al. Identification of a human HECT family protein with homology to the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene hyperplastic discs. Oncogene. 1998;17:3479–3491. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda Y, et al. Cooperation of HECT-domain ubiquitin ligase hHYD and DNA topoisomerase II-binding protein for DNA damage response. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3599–3605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson MJ, et al. EDD mediates DNA damage-induced activation of CHK2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39990–40000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien PM, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase EDD is an adverse prognostic factor for serous epithelial ovarian cancer and modulates cisplatin resistance in vitro. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1085–1093. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clancy JL, et al. EDD, the human orthologue of the hyperplastic discs tumour suppressor gene, is amplified and overexpressed in cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:5070–5081. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kan Z, et al. Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers. Nature. 2010;466:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nature09208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuja TJ, Lin F, Osann KE, Bryant PJ. Somatic mutations and altered expression of the candidate tumor suppressors CSNK1 epsilon, DLG1, and EDD/hHYD in mammary ductal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:942–951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang X, Chen W, Kim RH, Kang MK, Park NH. Regulation of the hTERT promoter activity by MSH2, the hnRNPs K and D, and GRHL2 in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:565–574. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka Y, et al. Gain of GRHL2 is associated with early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2008;49:746–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu G, et al. Modulation of myocardin function by the ubiquitin E3 ligase, UBR5. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11800–11809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilanowski T, et al. A highly conserved novel family of mammalian developmental transcription factors related to Drosophila grainyhead. Mech Dev. 2002;114:37–50. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray DC, et al. pHUSH: A single vector system for conditional gene expression. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7:61. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray D, et al. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase/murine protein serine-threonine kinase 38 is a promising therapeutic target for multiple cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9751–9761. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hupé P, Stransky N, Thiery JP, Radvanyi F, Barillot E. Analysis of array CGH data: from signal ratio to gain and loss of DNA regions. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3413–3422. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haverty PM, et al. High-resolution genomic and expression analyses of copy number alterations in breast tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:530–542. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]