Abstract

Tropical cyclones have massive economic, social, and ecological impacts, and models of their occurrence influence many planning activities from setting insurance premiums to conservation planning. Most impact models allow for geographically varying cyclone rates but assume that individual storm events occur randomly with constant rate in time. This study analyzes the statistical properties of Atlantic tropical cyclones and shows that local cyclone counts vary in time, with periods of elevated activity followed by relative quiescence. Such temporal clustering is particularly strong in the Caribbean Sea, along the coasts of Belize, Honduras, Costa Rica, Jamaica, the southwest of Haiti, and in the main hurricane development region in the North Atlantic between Africa and the Caribbean. Failing to recognize this natural nonstationarity in cyclone rates can give inaccurate impact predictions. We demonstrate this by exploring cyclone impacts on coral reefs. For a given cyclone rate, we find that clustered events have a less detrimental impact than independent random events. Predictions using a standard random hurricane model were overly pessimistic, predicting reef degradation more than a decade earlier than that expected under clustered disturbance. The presence of clustering allows coral reefs more time to recover to healthier states, but the impacts of clustering will vary from one ecosystem to another.

Keywords: climate change, climate variability, multidecadal variability

The devastating economic, social, and ecological impacts of tropical cyclones are well established (1–3). Estimates of hurricane rates are needed to model the dynamics of many ecological (4–6), social (7), and economic (8) processes. A key implicit assumption of virtually all such models is that cyclones occur randomly in time with a constant rate that can vary geographically. Using a century of cyclone tracks from the Atlantic (9), we begin by testing whether such a model of hurricanes is indeed appropriate. In areas where such models are found to be inappropriate, because hurricane events are in fact clustered in time rather than obeying a constant rate, we then investigate whether this departure from a Poisson process matters when predicting the health of Caribbean coral reefs. Important theories of disturbance ecology originated from coral reefs (2), making them a convenient system to pose this question. It should be noted that clustering of natural hazards such as hurricanes can also have a profound impact on nonecosystem features: For example, clustering can induce a substantially enhanced probability of multiple large insured losses within the duration of a single reinsurance contract (10).

Results and Discussion

Clustering of Hurricanes.

We examine tropical cyclone tracks from the Atlantic Basin Hurricane Database (HURDAT) between 1901 and 2010. Following the approach of Villarini et al. (11), we consider tracks lasting only for more than 2 d, to address partially the issues that have been raised about the quality of the HURDAT database in the early 20th century (12–16). Our analysis reveals clear patterns of geographic variability in the mean rates of tropical cyclones and hurricanes, the latter having more intense wind speeds that exceed 119 km h-1 (Fig. 1 A and B). Storm arrival rates vary in time because of the influence from large-scale modes of climate variability. Such variation causes storm counts to be more variable than expected for random independent storms having constant rate. Overdispersion, the exceedance of the variance of the counts above the mean of the counts, provides a simple method for quantifying this “clustering” above that expected for a constant rate Poisson process (10, 17). Note that this definition of clustering should not be confused with that arising from a clustered process caused by dependency between neighboring events (e.g., secondary cyclogenesis).

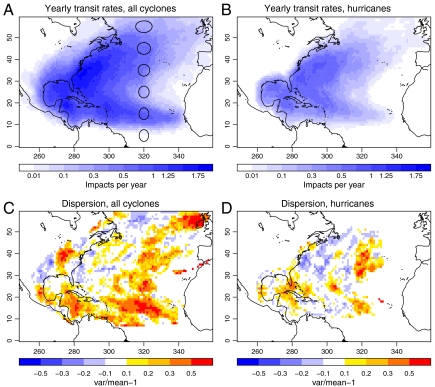

Fig. 1.

Mean yearly counts of (A) tropical cyclones and (B) more intense tropical cyclones (hurricanes) passing over circular regions with 300-km radius centered on points on a regular latitude–longitude grid with 1° spacing. The circles in A have equal radius of 300 km with distances measured along a great circle. Dispersion statistic of (C) tropical cyclones and (D) hurricanes.

The dispersion statistic of the tropical cyclone transits (Fig. 1C) is significantly greater than zero over much of the eastern Atlantic and particularly in the main hurricane development region, between the coast of Africa and the Caribbean Sea (18, 19). From the main development region, two large patches of overdispersion emerge. The first extends northward in the eastern Atlantic, and the second forms a “corridor” extending toward the Caribbean Sea. Significant overdispersion occurs within the Caribbean, and for some of the largest areas of reef development such as the south of Cuba and Jamaica, the Bahamas archipelago, the Florida Keys, and the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, which borders the land mass of Central America (Fig. 1D).

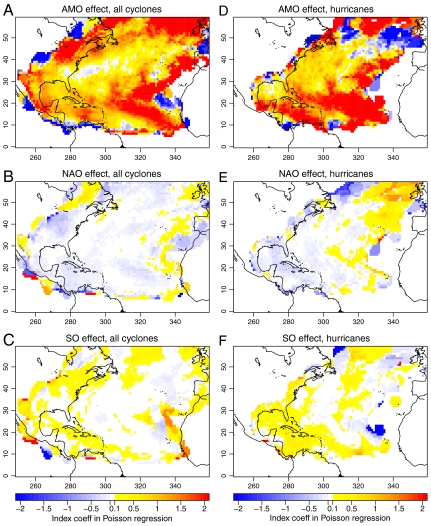

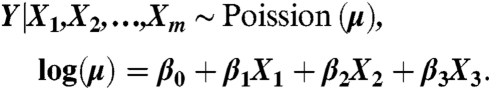

It is interesting to ask whether time variation in local rates can be related to changes in large-scale climate patterns. One way to answer this question is to perform a Poisson regression of counts on the large-scale flow indices, as has been done in previous studies but generally only for landfall or basinwide counts (20); also see refs. 21–29). The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) can be seen to have a pronounced effect on the yearly impact rates for all tropical cyclones and hurricanes (Fig. 2 A and C). The AMO is known to be linked to long-term variability of tropical cyclone and hurricane activity (30, 31). The North Atlantic Oscillation and the Southern Oscillation indices have a much smaller effect (Fig. 2 B and D), in broad agreement with earlier studies (30, 31).

Fig. 2.

Poisson regression coefficients of the indexes of Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, North Atlantic Oscillation, and Southern Oscillation (that is,β1, β2, and β3 in Eq. 1) for the yearly impact counts of all tropical cyclones (A–C) and hurricanes only (D–F).

Impact of Clustered Hurricane Events on Ecosystems.

We asked whether the observed levels of hurricane clustering (Fig. 1) are sufficient to cause a significant change in coral reef state. To do this we used a spatial simulation model of a Caribbean coral reef under realistic levels of hurricane disturbance. The model simulates the population dynamics of several growth forms of coral under both chronic and acute disturbance. A detailed model parameterisation is given in SI Text, and its predictions have been validated against a long-term empirical dataset from Jamaica during which multiple hurricanes occurred (32).

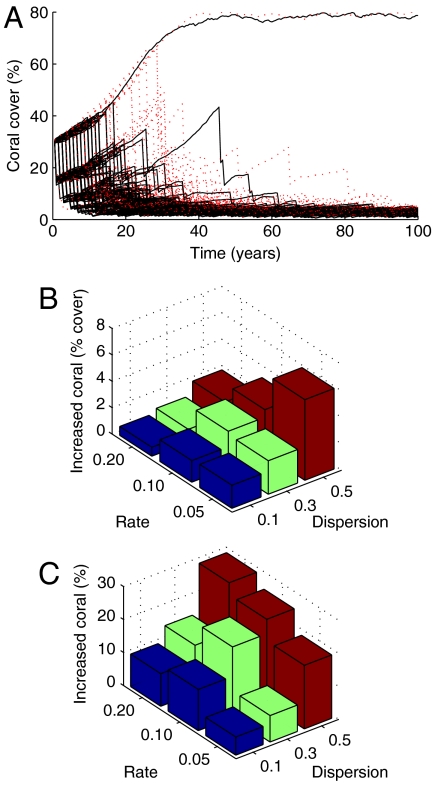

For three representative rates of annual hurricane incidence (0.05, 0.10, 0.20) we compared the overall health of reefs under four models of temporal dispersion: a null model of random hurricane events, and three representative levels of overdispersion (0.1, 0.3, 0.5). We initialized reefs with a moderately healthy coral cover of 30% and assumed that reefs were well managed with high fish herbivory, high natural algal productivity, and no sedimentation. The long-spined sea urchin, which was decimated by disease in 1983 (33), was assumed to be functionally absent in the reef habitat and depth modeled. Background levels of coral mortality were included, but we ignored ocean acidification and coral bleaching so as to focus specifically on the impact of hurricanes.

Under fairly intense hurricane rates (> 0.1 per annum), overall coral cover declined during the century, emphasizing the problems faced by today’s reefs, which often lack a major class of branching corals (34) and experience an undergrazed environment lacking a major group of herbivores (32). However, individual reef trajectories under clustered hurricanes tended to be healthier for longer than those experiencing random hurricane events at the same rate (Fig. 3A). Indeed, average coral cover was always greater under clustered hurricanes and the magnitude of this “mitigation” increased, often nonlinearly, with mounting overdispersion (Fig. 3 B and C). Comparing the response across different rates of hurricane, the effects of clustering were also nonlinear; reefs experiencing intermediate rates of disturbance (0.1) responded relatively strongly to modest clustering in disturbance (Fig. 3C). The exceptional response of reefs under intermediate disturbance arises because more frequent events maintain the system in a highly degraded state, thereby attenuating the scope for recovery, and reefs experiencing less frequent events spend so little time in a degraded state that the century-averaged response to hurricanes is minor.

Fig. 3.

Impacts of clustered versus random hurricanes after a century of disturbance showing examples of individual reef trajectories (A). Increases in century-averaged coral cover under clustered events are expressed both in absolute units of cover (B) and in relative terms where the increase is given as a percentage of the mean century-averaged cover under random hurricane events (C). Individual trajectories (A) shown for a hurricane rate of 0.2 and comparison of randomly dispersed hurricanes (black) with those at an overdispersion of 0.5 (red).

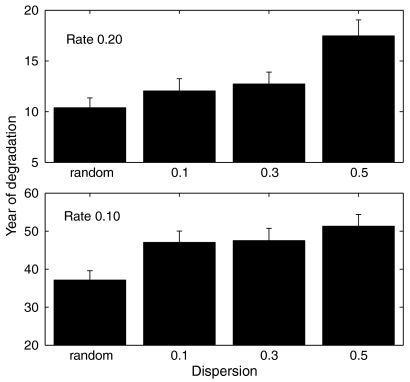

To synthesize our results, we determined the year at which reefs become functionally degraded under a sustained hurricane regime. We loosely define “degraded” as having occurred once at least 95% of the subsequent reef observations remain in a degraded state of < 10% cover. Degradation was found only under the higher hurricane rates but clustering delayed the onset of degradation considerably: by 6 y under frequent hurricanes and 14 y under intermediate hurricane rates (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Delays to the degradation of coral reef ecosystems under clustered versus random sequences of hurricanes. Degradation was defined as having occurred once coral cover remained below 10% for > 95% of subsequent time steps. The earlier the degradation occurs, the longer the reef remains in a degraded state.

Although cyclones damage reefs, our results imply that a strongly clustered hurricane regime will allow ecosystems to remain in a later successional state for a greater proportion of the time. If a system has not been struck for some time, the first hurricane event will often have a devastating impact and remove many of the vulnerable organisms (35). If the next hurricane occurs before much recovery has taken place (i.e., as part of a cluster of events), its impact may be relatively weak because few vulnerable individuals remain and ecosystem recovery remains at a nascent stage that limits the addition of new susceptible colonies (36, 37). Indeed, a metaanalysis of hurricane impacts on 286 reefs found that time elapsed since the previous hurricane event was a major positive correlate of subsequent damage (38), which provides supporting empirical evidence that clustered events should, on average, damage the ecosystem less. Comparable variations in hurricane impact during successive events have been reported in other ecosystems including tropical forests (6, 39) and oyster beds (40).

Our conclusions are likely to be conservative in that the “mitigative benefits” of clustered disturbance are likely to be underestimated in our analysis of reef ecosystems, largely because our simple model captures some, but not all, of the vulnerability among individual corals to hurricane damage. In our model, vulnerability is implemented as a function of coral size, but additional variability is likely among individuals by virtue of their phenotypic expression (e.g., shape) and local microhabitat (e.g., proneness of their underlying substrate to collapse). Our model does not resolve such small-scale effects, but these would tend to increase the disparity of impacts between successive hurricane events and increase the “mitigative effect” of clustered versus Poisson processes.

The reef framework built by living corals underpins several important ecosystem services including coastal protection from storms, reef fisheries, and the generation of sand for building materials and beach tourism. Given that reefs are increasingly disturbed by the El Niño–Southern Oscillation phenomenon, climate change, and overexploitation (41), most exist in a transient state, rarely reaching a truly late successional community composition. However, the principle remains that a reef in a higher state of recovery will tend to have higher cover, a later successional state, and offer higher levels of reef-based ecosystem services.

Hurricanes are a major structuring force in terrestrial (42, 43), estuarine (44), and aquatic systems (45). The impact of hurricane clustering on ecosystems will depend on their vulnerability to hurricane damage, the consequences of remaining in a damaged state during successive clustered hurricane events (even if followed by an extended recovery phase), and the relative rates of ecosystem recovery and hurricane incidence. For example, an ecosystem experiencing severe Allee effects (46) after a hurricane might be negatively impacted by clustering. The next Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment will place renewed effort in determining the effects of climate change on cyclone activity. Predictions of climate change in hurricane-prone ecosystems should consider the clustered nature of events as these can have a significant bearing on results. For coral reefs in the Atlantic, hurricanes are sufficiently clustered to alter the predictions of ecosystem degradation by more than a decade.

Methods

We considered cyclones passing over disks of radius 300 km in order to capture the damaging footprint of strong surface winds distributed asymmetrically about the eye of the storms (47). We count the yearly number of impacts of tracks on disks of radius R = 300 km centered at grid points with spacing 1° on a domain surrounding the North Atlantic. This gives a time series Y = {y1,…,y10} of counts for each grid point. The dispersion statistic is defined as  , where y is the sample mean and

, where y is the sample mean and  is the sample variance of the counts. If the process of cyclone transit is totally random (that is, events are independent of each other) and stationary, then the counts should follow a Poisson distribution and so have φ = 0. Therefore, φ > 0 indicates overdispersion compared to a constant mean Poisson distribution and provides a measure of serial (temporal) clustering of the cyclone transit process (10, 11). The same analysis is performed for hurricane impacts, which are counted when the maximum wind speed within a disk is larger than 119 km h-1.

is the sample variance of the counts. If the process of cyclone transit is totally random (that is, events are independent of each other) and stationary, then the counts should follow a Poisson distribution and so have φ = 0. Therefore, φ > 0 indicates overdispersion compared to a constant mean Poisson distribution and provides a measure of serial (temporal) clustering of the cyclone transit process (10, 11). The same analysis is performed for hurricane impacts, which are counted when the maximum wind speed within a disk is larger than 119 km h-1.

For Poisson regression we fitted the model

|

This expresses the rate μ as a function of the time-varying covariates, which in our case are indexes for the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO, the undetrended unsmoothed data), from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/timeseries/AMO/, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and the Southern Oscillation (SO), from the Climate Research Unit: http://www.cru.uea.ac.uk/cru/data. Following Elsner et al. (23), for every year in the record we took August–October averages of the monthly values of the AMO and SO indices and May–June pre-hurricane-season averages of the monthly values of the NAO index.

Each coral reef simulation was run for a period of 100 y. Each combination of hurricane rate and dispersion was repeatedly simulated 100 times and the mean response reported in figures. Although the simulation of disturbances was probabilistic, only those disturbance regimes that conformed exactly to the overall long-term disturbance rate (e.g., five events over 100 y for a rate of 0.05) were included, which ensured that comparisons between disturbance regimes were not confounded by minor statistical noise. Statistical analyses were not undertaken because they would have limited meaning: We could always increase the number of simulations to obtain a significant difference among treatments. Further details of the model are given in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

P.J.M. was funded by an Australian Research Council Laureate Fellowship and the European Union Force project. R.V. and D.B.S. gratefully acknowledge the Willis Research Network for their support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1100436108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pielke RAJ, Pielke RAS. Hurricanes: Their Nature and Impacts on Society. New York: Wiley; 1997. p. 279. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connell JH. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science. 1978;199:1302–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.199.4335.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baade RA, Baumann R, Matheson V. Estimating the economic impact of natural and social disasters, with an application to hurricane Katrina. Urban Stud. 2007;44:2061–2076. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busby PE, Motzkin G, Boose ER. Landscape-level variation in forest response to hurricane disturbance across a storm track. Can J For Res. 2008;38:2942–2950. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckage B, Gross LJ, Platt WJ. Modelling responses of pine savannas to climate change and large-scale disturbance. Appl Veg Sci. 2006;9:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uriarte M, et al. Natural disturbance and human land use as determinants of tropical forest dynamics: Results from a forest simulator. Ecol Monogr. 2009;79:423–443. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duit A, Galaz V. Governance and complexity—Emerging issues for governance theory. Governance. 2008;21:311–335. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbier EB. Ecosystems as natural assets. Found Trends Microeconomics. 2008;4:611–681. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvinen BR, Neumann CJ, Davis MAS. Miami: Natl Hurricane Center; 1984. A tropical cyclone database for the North Atlantic Basin, 1886–1983: Contents, limitations and uses; pp. 1–24. NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC 22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitolo R, Stephenson DB, Cook IM, Mitchell-Wallace K. Serial clustering of intense European storms. Meteorologische Zeitscrift. 2009;18:411–424. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villarini G, Vecchi GA, Smith JA. Modeling the dependence of tropical storm counts in the North Atlantic basin on climate indices. Monthly Weather Rev. 2010;138:2681–2705. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landsea C. Counting Atlantic tropical cyclones back to 1990. EOS Trans AGU. 2007;88:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landsea CW, Vecchi GA, Bengtsson L, Knutson TR. Impact of duration thresholds on Atlantic tropical cyclone counts. J Clim. 2010;23:2508–2519. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang EKM, Guo Y. Is the number of north Atlantic tropical cyclones significantly underestimated prior to the availability of satellite observations? Geophys Res Lett. 2007;34:L14801. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vecchi GA, Knutson TR. On estimates of historical north Atlantic tropical cyclone activity. J Clim. 2008;21:3580–3600. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vecchi GA, Knutson TR. Estimating annual numbers of Atlantic hurricanes missing from the Hurdat database (1878–1965) using ship track density. J Clim. 2011;24:1736–1746. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mailier PJ, Stephenson DB, Ferro CAT, Hodges KI. Serial clustering of extratropical cyclones. Monthly Weather Rev. 2006;134:2224–2240. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emanuel KA. The hurricane-climate connection. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2008;89:ES10–ES20. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldenberg SB, Landsea CW, Mestas-Nunez AM, Gray WM. The recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity: Causes and implications. Science. 2001;293:474–479. doi: 10.1126/science.1060040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsner JB, Schmertmann CP. Improving extended-range seasonal predictions of intense Atlantic hurricane activity. Weather Forecast. 1993;8:345–351. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elsner JB. Tracking hurricanes. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2003;84:353–356. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsner JB, Bossak BH, Niu XF. Secular changes to the ENSO-US hurricane relationship. Geophys Res Lett. 2001;28:4123–4126. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsner JB, Murnane RJ, Jagger TH. Forecasting US Hurricanes 6 months in advance. Geophys Res Lett. 2006;33:L10704. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mooley DA. Applicability of the Poisson probability model to the severe cyclonic storms striking the coast around the Bay of Bengal. Sankhya. 1981;43B:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson ML, Guttorp P. A probability model for severe cyclonic storms striking the coast around the Bay of Bengal. Monthly Weather Rev. 1986;114:2267–2271. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solow A, Nicholls N. The relationship between the Southern Oscillation and tropical cyclone frequency in the Australian region. J Clim. 1990;3:1097–1101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solow AR, Moore L. Testing for a trend in a partially incomplete hurricane record. J Clim. 2000;13:3696–3699. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parisi F, Lund R. Return periods of continental US hurricanes. J Clim. 2008;21:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonnell KA, Holbrook NJ. A Poisson regression model of tropical cyclogenesis for the Australian–Southwest Pacific ocean region. Weather Forecast. 2004;19:440–455. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enfield DB, Cid-Serrano L. Secular and multidecadal warmings in the north Atlantic and their relationships with major hurricane activity. Int J Climatology. 2010;30:174–184. 10.1002/joc.1881. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villarini G, Vecchi GA, Smith JA. Modeling of the dependence of tropical storm counts in the North Atlantic Basin on climate indices. Monthly Weather Rev. 2010;138:2681–2705. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mumby PJ, Hastings A, Edwards HJ. Thresholds and the resilience of Caribbean coral reefs. Nature. 2007;450:98–101. doi: 10.1038/nature06252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lessios HA, Robertson DR, Cubit JD. Spread of Diadema mass mortality through the Caribbean. Science. 1984;226:335–337. doi: 10.1126/science.226.4672.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bythell J, Sheppard C. Mass mortality of Caribbean shallow corals. Mar Pollut Bull. 1993;26:296–297. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes TP. Community structure and diversity of coral reefs: The role of history. Ecology. 1989;70:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes TP. Catastrophes, phase shifts, and large-scale degradation of a Caribbean coral reef. Science. 1994;265:1547–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.265.5178.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mumby PJ, Foster NL, Glynn Fahy EA. Patch dynamics of coral reef macroalgae under chronic and acute disturbance. Coral Reefs. 2005;24:681–692. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gardner TA, Côté IM, Gill JA, Grant A, Watkinson AR. Hurricanes and Caribbean coral reefs: Impacts, recovery pattterns, and role in long-term decline. Ecology. 2005;86:174–184. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostertag R, Silver WL, Lugo AE. Factors affecting mortality and resistance to damage following hurricanes in a rehabilitated subtropical moist forest. Biotropica. 2005;37:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livingston RJ, Howell RL, Niu XF, Lewis FG, Woodsum GC. Recovery of oyster reefs (Crassostrea virginica) in a gulf estuary following disturbance by two hurricanes. Bull Mar Sci. 1999;64:465–483. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science. 2007;318:1737–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.1152509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flynn DFB, et al. Hurricane disturbance alters secondary forest recovery in Puerto Rico. Biotropica. 2010;42:149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uriate M, Papaik M. Hurricane impacts on dynamics, structure and carbon sequestration potential of forest ecosystems in southern New England, USA. Tellus A Dynamic Meteorology Oceanography. 2007;59:519–528. 10.1111/j.1600-0870.2007.00243.x. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross MS, et al. Early post-hurricane stand development in fringe mangrove forests of contrasting productivity. Plant Ecol. 2006;185:283–297. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown KM, Daniel W, George G. The effect of hurricane Katrina on the mussel assemblage of the Pearl River, Louisiana. Aquatic Ecology. 2010;44:223–231. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Courchamp F, Berec L, Gascoigne J. Allee Effects in Ecology and Conservation. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ Press; 2009. p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keim BD, Muller RA, Stone GW. Spatiotemporal patterns and return periods of tropical storm and hurricane strikes from Texas to Maine. J Clim. 2007;20:3498–3509. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.