Abstract

Neurovascular coupling is a process through which neuronal activity leads to local increases in blood flow in the central nervous system. In brain slices, 100% O2 has been shown to alter neurovascular coupling, suppressing activity-dependent vasodilation. However, in vivo, hyperoxia reportedly has no effect on blood flow. Resolving these conflicting findings is important, given that hyperoxia is often used in the clinic in the treatment of both adults and neonates, and a reduction in neurovascular coupling could deprive active neurons of adequate nutrients. Here we address this issue by examining neurovascular coupling in both ex vivo and in vivo rat retina preparations. In the ex vivo retina, 100% O2 reduced light-evoked arteriole vasodilations by 3.9-fold and increased vasoconstrictions by 2.6-fold. In vivo, however, hyperoxia had no effect on light-evoked arteriole dilations or blood velocity. Oxygen electrode measurements showed that 100% O2 raised pO2 in the ex vivo retina from 34 to 548 mm Hg, whereas hyperoxia has been reported to increase retinal pO2 in vivo to only ∼53 mm Hg [Yu DY, Cringle SJ, Alder VA, Su EN (1994) Am J Physiol 267:H2498-H2507]. Replicating the hyperoxic in vivo pO2 of 53 mm Hg in the ex vivo retina did not alter vasomotor responses, indicating that although O2 can modulate neurovascular coupling when raised sufficiently high, the hyperoxia-induced rise in retinal pO2 in vivo is not sufficient to produce a modulatory effect. Our findings demonstrate that hyperoxia does not alter neurovascular coupling in vivo, ensuring that active neurons receive an adequate supply of nutrients.

Keywords: functional hyperemia, glial cells, prostaglandins

Neuronal activity in the CNS induces local increases in blood flow (1, 2), a homeostatic response termed functional hyperemia. Neurovascular coupling, the process mediating this response, is thought to involve signaling from neurons to glial cells to blood vessels. Neuronal activity induces a rise in intracellular Ca2+ in glial cell endfeet surrounding vessels, leading to the release of vasoactive arachidonic acid metabolites and resulting in vasomotor responses (2–6). Experiments in brain slices and in the ex vivo retina have revealed that glial activation can evoke both vasodilation and vasoconstriction. Evoked vasodilations are mediated by cyclooxygenase (COX) products (3, 5) and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) (6–9), whereas vasoconstrictions are mediated by 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) (4, 6).

A recent study demonstrated that neurovascular coupling is modulated by O2 in brain slices (10). Both neuronal and glial cell stimulation elicited vasodilations in brain slices exposed to 20% O2. In contrast, vasoconstrictions were evoked in the presence of 100% O2. However, another recent study reported the opposite effect of O2 in vivo (11). In that study, increasing systemic O2 using hyperbaric hyperoxygenation had no effect on cortical functional hyperemia. Resolving these conflicting findings is critical, given that hyperoxia (breathing 100% O2) is often used in the clinic during the course of therapy, and a reduction in neurovascular coupling could deprive active neurons of adequate nutrients. Indeed, hyperoxia is sometimes used to treat premature infants, and high O2 is believed to contribute to retinopathy of prematurity (12).

In the present work, we address the issue of O2 modulation by investigating neurovascular coupling in the retina, using both ex vivo and in vivo preparations. Our results show that although O2 profoundly modulates neurovascular coupling in the ex vivo retina, breathing 100% O2 does not alter neurovascular coupling in vivo. This discrepancy arises because the partial pressure of O2 (pO2) within the retina in vivo during 100% O2 respiration does not rise to a sufficiently high level to affect neurovascular signaling pathways.

Results

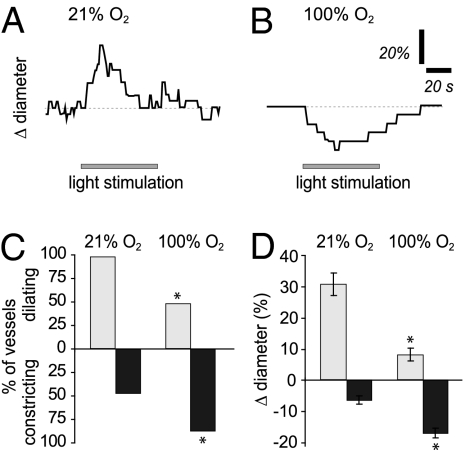

We first examined the effect of O2 on flicker-induced arteriole dilation in the ex vivo retina. Retinas were superfused with solutions equilibrated with either 21% or 100% O2, and arterioles on the vitreal surface of the retina were imaged with infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) microscopy. In 21% O2, light stimulation evoked vasodilation in 97.5% of the vessels studied (n = 40), with an average diameter change of 30.8% ± 3.7% (Fig. 1 A, C, and D). In approximately half of the vessels (47.5%), the initial dilation was followed by constriction, which averaged 6.6% ± 1.4%. In contrast, in 100% O2, only 50% of the vessels dilated in response to light stimulation (n = 40; P < 0.001), with the average dilation reduced to 8.0% ± 2.0% (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1 B–D). The incidence of light-evoked vasoconstrictions, on the other hand, increased to 87.5% (P < 0.001) in high O2 and averaged 17.3% ± 1.7% (P < 0.005). Oxygen did not affect the resting tone of the arterioles studied. The average resting diameter was 21.5 ± 1.5 μm in low O2 and 22.5 ± 1.5 μm in high O2 (P > 0.6). These results demonstrate that O2 modulates neurovascular coupling in the ex vivo retina, in agreement with previous findings in brain slices (10).

Fig. 1.

Light-evoked vasodilation is reduced and vasoconstriction is increased in 100% O2 in the ex vivo retina. (A) Time course of a light-evoked arteriole response in a retina exposed to 21% O2. (B) Time course of a light-evoked arteriole response in a retina exposed to 100% O2. (C) Incidence of light-evoked arteriole dilations and constrictions in 21% and 100% O2. Fewer vessels dilate and more vessels constrict in high O2. Vessels that showed biphasic responses are included in both the dilation and constriction data. (D) Amplitude of light-evoked arteriole dilations and constrictions in 21% and 100% O2. The amplitude of vasodilations is reduced and that of vasoconstrictions is increased in high O2. *P < 0.005.

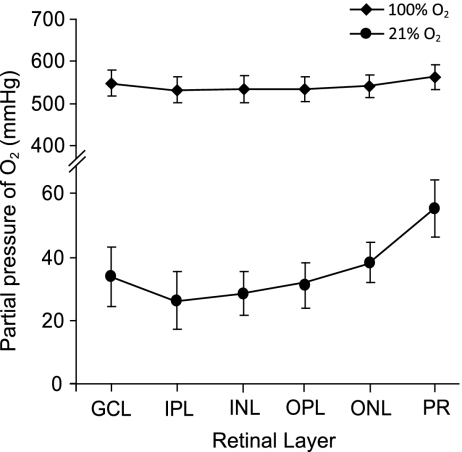

We measured tissue O2 tension in the ex vivo retina with O2-sensitive microelectrodes to determine retinal pO2 in low and high O2 conditions. pO2 in retinas exposed to 21% O2 equaled 33.6 ± 9.5 mm Hg in the ganglion cell layer (Fig. 2; n = 5), somewhat higher than the physiological range of 16–24 mm Hg reported in vivo (13). When retinas were exposed to 100% O2, pO2 in the ganglion cell layer was increased by more than 16-fold, to 547.7 ± 30.3 mm Hg (n = 7; P < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Partial pressure of O2 within the ex vivo retina exposed to 21% and 100% O2. Retinas perfused with 100% O2-bubbled saline had a much higher pO2 in all retinal layers. GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; PR, photoreceptors.

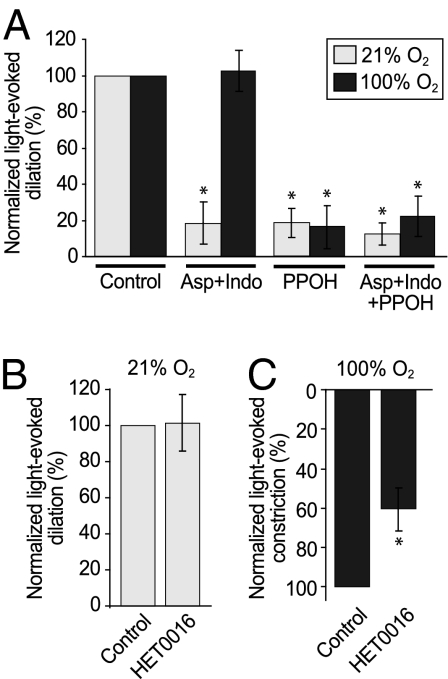

Both prostaglandin E2 and EETs have been implicated in mediating vasodilation in the CNS (3, 5, 6, 8), and findings from brain slices have indicated that the prostaglandin (PG) component is suppressed by high O2 (10). Thus, we investigated the pathways responsible for the O2 modulation of light-evoked vasomotor responses in the ex vivo retina. We first identified vessels that dilated robustly to light stimulation, and then examined the responses of these vessels after application of inhibitors of arachidonic acid metabolism. We tested the PG pathway by applying the COX inhibitors aspirin (50 μM) and indomethacin (5 μM) and the EETs pathway by inhibiting its synthetic enzyme, epoxygenase, with 2-(2-propynyloxy)-benzenehexamoic acid (PPOH; 20 μM). In low O2, COX inhibition reduced light-evoked vasodilations by 81.9% (n = 8; P < 0.01), whereas in high O2, COX inhibition had no effect (n = 13; P = 0.8; Fig. 3A). The absence of a COX-dependent vasodilating component in high O2 most likely arises because the PG pathway is already suppressed by O2. In contrast, inhibiting epoxygenase reduced the amplitude of light-evoked vasodilation in both low and high O2. Dilations were reduced by 83.4% in high O2 (n = 7) and by 81.5% in low O2 (n = 5; P < 0.05 for both; Fig. 3A). Inhibiting both COX and epoxygenase together also inhibited light-evoked vasodilation in both conditions, but to no greater extent than when either pathway was inhibited separately. Dilations were reduced by 77.7% in high O2 (n = 6; P < 0.01) and by 87.7% in low O2 (n = 11; P < 0.001; Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

COX-mediated vasodilation is suppressed and 20-HETE–mediated constriction is enhanced in 100% O2 in the ex vivo retina. (A) The COX inhibitors aspirin (50 μM) and indomethacin (5 μM) together reduced light-evoked vasodilation in retinas exposed to 21% O2, but not in those exposed to 100% O2. The epoxygenase inhibitor PPOH (20 μM) reduced vasodilation in both low and high O2 conditions. Aspirin, indomethacin, and PPOH, applied together to block both COX and epoxygenase, inhibited vasodilation in both 21% and 100% O2. (B and C) The ω-hydroxylase inhibitor HET0016 had no effect on the vascular responses observed in 21% O2 (B), but reduced the amplitude of vasoconstrictions in 100% O2 (C). Control and drug treatment data were from the same set of vessels for each inhibitor. *P < 0.05, paired t test.

These results support the view that high O2 suppresses the PG component, but not the EETs component, of neurovascular coupling; however, they do not account for the increase in vasoconstriction observed in high O2. The arachidonic acid metabolite 20-HETE has been shown to mediate vasoconstrictions in both the brain and the retina (4, 6), and its synthetic enzyme, ω-hydroxylase, has been proposed to be a microvascular O2 sensor (14). We investigated the contribution of 20-HETE to vasomotor responses in the two O2 conditions using the ex vivo retina. We first identified vessels that displayed light-evoked constrictions in high O2, and then tested their response after treatment with HET0016 (100 nM), an ω-hydroxylase inhibitor. HET0016 reduced light-evoked vasoconstrictions in high O2 by 40.4% (n = 10; P < 0.05; Fig. 3C). In low O2, it was not feasible to assess the effect of HET0016 on constrictions, because such responses occurred infrequently. Nevertheless, if 20-HETE were produced in response to light-evoked neuronal activity, then inhibiting the production of this vasoconstrictor should result in larger dilations. However, in 21% O2, HET0016 had no effect on the amplitude of vasodilation (n = 9; P = 0.3; Fig. 3B). These results indicate that 20-HETE does not contribute noticeably to neurovascular coupling in low O2, but mediates vasoconstrictions in high O2.

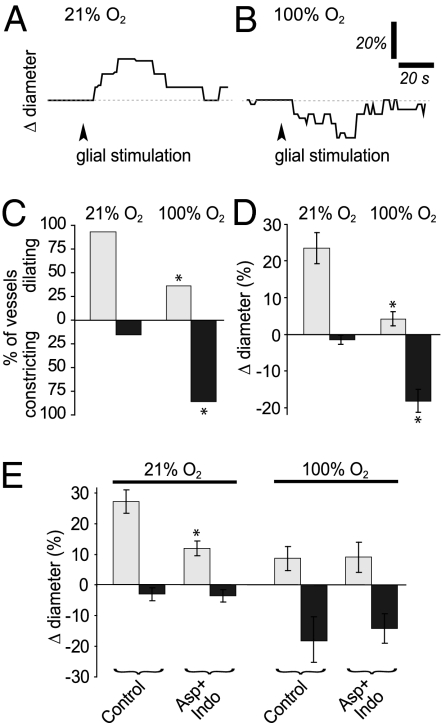

There is accumulating evidence that neurovascular coupling is partially mediated by glia-to-vessel signaling (2). We tested whether O2 control of neurovascular coupling occurs via modulation of glia-to-vessel signaling by observing glial-evoked vasomotor responses in the two O2 conditions. Glial cells were stimulated by focal ejection of ATP, which evokes Ca2+ waves that propagate through astrocytes and Müller cells, the macroglial cells of the retina. In low O2, glial stimulation evoked dilations in 92.3% of the vessels, with an amplitude of 23.5% ± 4.1% (n = 13; Fig. 4 A, C, and D). Only 15.4% of vessels constricted, usually after an initial dilation, with an average amplitude of 1.5% ± 1.2%. In contrast, in high O2, only 35.7% (P < 0.01) of the vessels dilated to glial stimulation, with an amplitude of 4.3% ± 1.8% (n = 14; P < 0.001; Fig. 4 C and D). As with light stimulation, the percentage of constricting vessels increased to 85.7% (P < 0.01), and the average amplitude of the constrictions increased to 18.1% ± 3.1% (P < 0.001; Fig. 4 B–D). These data suggest that O2 modulation of neurovascular coupling occurs, at least in part, by regulating glial cell-to-vessel signaling.

Fig. 4.

Glial-evoked vasodilation is reduced and vasoconstriction is increased in 100% O2 in the ex vivo retina. (A) Time course of arteriole dilation evoked by an ATP-induced glial Ca2+ wave in 21% O2. (B) Time course of a similarly evoked arteriole response in 100% O2. The arteriole constricted in response to glial stimulation. (C) Incidence of glial-evoked vascular responses in 21% and 100% O2. Fewer dilations and more constrictions occurred in high O2. (D) Amplitude of glial-evoked arteriole dilations and constrictions in 21% and 100% O2. Vasodilations were smaller and vasoconstrictions were larger in high O2. (E) COX inhibitors aspirin (50 μM) and indomethacin (5 μM) together reduced glial-evoked vasodilation in retinas exposed to 21% O2, but not in those exposed to 100% O2. *P < 0.01.

We tested whether the reduction in glial-evoked vasodilation that we observed in high O2 was due to a reduction of PG signaling, as was the case for light-evoked dilations. In low O2, glial-evoked dilations averaged 27.2% ± 3.8% (n = 11) in control solution, but were significantly reduced to 12.0% ± 2.4% after COX inhibition (n = 11; P < 0.005; Fig. 4E). In high O2, in contrast, COX inhibitors had no effect. Glial-evoked dilations averaged 8.7% ± 3.9% in control solution and 9.0% ± 4.8% after drug treatment (n = 6; P = 0.4; Fig. 4E). The results demonstrate that suppression of glial-evoked vasodilation in high O2 occurs via the PG signaling pathway, as in light-evoked vasodilation.

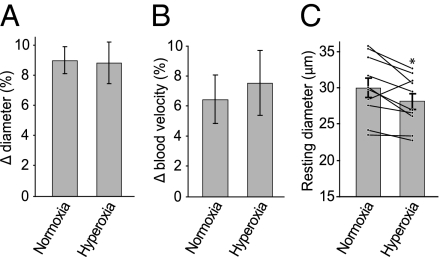

These findings illustrate that O2 has a substantial effect on neurovascular coupling in the ex vivo retina. Whether O2 has a similar modulatory effect in vivo remains controversial, however. We tested this by monitoring vascular diameter and blood velocity in the retinas of anesthetized rats. Switching animals from normoxic conditions (arterial pO2 117 ± 7 mm Hg) to hyperoxic conditions (arterial pO2 512 ± 26 mm Hg; Table 1) by artificially ventilating them with 100% O2 produced no change in the evoked vasomotor responses. Under normoxia, diffuse flickering light stimulation evoked arteriolar dilations averaging 9.0% ± 0.9% (Fig. 5A) and blood velocity increases of 6.5% ± 1.6% (Fig. 5B). Under hyperoxia, light stimulation evoked vessel dilations of 8.8% ± 1.4% (P > 0.8) and blood velocity increases of 7.6% ± 2.2% (P > 0.1), neither of which was significantly different from the responses in normoxia.

Table 1.

Physiological parameters of anesthetized rats under normoxic and hyperoxic conditions

| Normoxia | Hyperoxia | |

| Mean arterial O2 saturation, % | 95.7 ± 0.5 | 98.5 ± 0.1* |

| Mean arterial partial pressure of O2, mm Hg | 117 ± 7 | 512 ± 26* |

| Mean arterial blood pressure, mm Hg | 118 ± 3 | 122 ± 4 |

| Mean pH | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 |

*P < 0.001.

Fig. 5.

Effect of O2 on light-evoked vascular responses and tone in vivo. (A) Flickering light evoked dilation of retinal arterioles in both normoxia and hyperoxia. (B) Flickering light evoked an increase in arterial blood velocity in both normoxia and hyperoxia. Neither the amplitude of the dilation nor the increase in blood velocity was significantly different in normoxic and hyperoxic conditions. (C) Resting arteriole diameter decreased after hyperoxia treatment. Bars depict average diameter of arterioles during normoxia and hyperoxia. Black lines show diameter change for individual arterioles. Eight of 10 vessels constricted during hyperoxia. *P < 0.001 (paired t test).

The resting tone of the arterioles, however, was significantly altered by hyperoxia. After the switch to 100% O2, arterioles displayed a large transient constriction, followed by a partial recovery. After stabilization under hyperoxia, arteriolar diameter averaged 27.6 ± 1.1 μm, compared with the average diameter of 29.4 ± 1.4 μm in the same vessels during normoxia, reflecting a decrease of 6.1% (P < 0.05; paired t test; Fig. 5C). There was no change in mean arterial blood pressure between normoxic and hyperoxic conditions (Table 1).

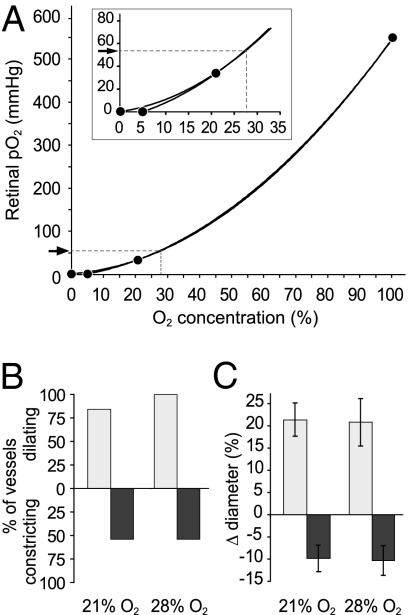

These results highlight a profound difference in neurovascular coupling ex vivo and in vivo; high O2 reduces neurovascular coupling substantially in the ex vivo retina, but not the in vivo retina. Resolution of this conflict may lie in pO2 differences within the retina in the two preparations. Our O2 electrode measurements (Fig. 2) show that pO2 in the ganglion cell layer of the ex vivo retina increases dramatically from 34 to 548 mm Hg when switching from 21% to 100% O2. In contrast, pO2 in the ganglion cell layer in vivo has been reported to increase only modestly, from ∼21 mm Hg to ∼53 mm Hg, when switching from normoxic to hyperoxic conditions (15). This small increase in O2 tension within the retina in vivo might not be sufficient to induce the modulatory changes in neurovascular coupling observed in the ex vivo retina.

We tested whether raising retinal pO2 to 53 mm Hg in the ex vivo preparation results in a modulation of neurovascular coupling. Based on our ex vivo pO2 measurements (Fig. 2), we calculated that bubbling the ex vivo superfusate with 28% O2 should produce a retinal pO2 of 53 mm Hg, reproducing the pO2 level in vivo during hyperoxia (Fig. 6A). We found that the incidence and amplitude of light-evoked arteriole responses in retinas exposed to 28% O2 were similar to those observed in the same vessels in 21% O2 (Fig. 6 B and C). Vasodilations averaged 20.8% ± 5.4% and vasoconstrictions averaged 10.3% ± 3.3% in 28% O2, compared with 21.4% ± 3.8% (P = 0.3) and 9.9% ± 2.9% (P > 0.9), respectively, in 21% O2 (n = 13). These results support the concept that O2 modulation is absent in vivo, because the small rise in tissue pO2 occurring during hyperoxia is not sufficiently large to affect neurovascular coupling.

Fig. 6.

Raising O2 in the ex vivo retina to mimic the pO2 in the hyperoxic in vivo retina has no effect on light-evoked vascular responses. (A) pO2 measured in the ganglion cell layer of the ex vivo retina is plotted against the bubbling O2 concentration (data from Fig. 2). The percentage of bubbling O2 that yields a pO2 of 53 mm Hg (pO2 in the hyperoxic retina in vivo, arrow; ref. 13) in the ex vivo retina is estimated by interpolation (shown by dashed lines in the figure and inset). Bubbling saline with 28% O2 results in a retinal pO2 of 53 mm Hg in the ex vivo preparation. Note that the second-order polynomial fit is similar whether pO2 is assumed to be 0 when bubbling O2 is 0% or 5%. (B and C) Neither the incidence (B) nor the amplitude (C) of light-evoked vasodilations and vasoconstrictions in the ex vivo retina changed when O2 was raised from 21% to 28%. Experiments shown in B and C are from the same set of vessels.

Discussion

We have shown that in the ex vivo rat retina, both light- and glial-evoked vascular responses are modulated by O2, and that this modulation is due to altered arachidonic acid signaling. Both PGs and EETs mediate vasodilation under low O2 conditions, but the contribution of PGs is absent under high O2 conditions, causing a substantial decrease in the incidence and amplitude of light- and glial-evoked vasodilations. These results confirm the findings of the MacVicar group indicating that PG-mediated vasodilation is reduced by high O2 in brain slices (10).

Oxygen also modulates 20-HETE signaling in the ex vivo retina. In low O2, 20-HETE has little effect on light-evoked vascular responses, but in high O2, a substantial component of light-evoked vasoconstriction is mediated by the 20-HETE pathway. A similar 20-HETE–dependent vasoconstriction in the ex vivo retina and in brain slices has been reported previously (4, 6). Oxygen modulation of the 20-HETE pathway may be related to the O2 dependence of 20-HETE synthesis, which has a reported KmO2 of 60–70 mm Hg (14). In contrast, the KmO2 of both COX1 and COX2 is reportedly ∼10 mm Hg (10 μM) (16), and that of EETs production is <10 mm Hg (14). Therefore, the synthesis of PG and EETs would not be depressed nearly as much as that of 20-HETE at physiological pO2 levels, which are ∼12–38 mm Hg in the CNS (17–21).

Oxygen modulates both light- and glial-evoked vasomotor responses in the ex vivo retina in a similar manner, suggesting that the modulatory effect of O2 occurs in glial cells or in downstream pathways. This finding is consistent with previous work demonstrating that PG is released from glial cells (22, 23), and that 20-HETE synthesis occurs downstream at the level of vascular smooth muscle cells (24). These results also clarify why we did not previously observe a PG component of neurovascular coupling in the ex vivo retina (6); that earlier ex vivo study was conducted entirely in 95% O2, effectively suppressing the PG component of the response.

In contrast to our ex vivo results, flicker-evoked vascular responses in vivo were not modulated by O2. Neither the flicker-evoked arteriole vasodilation nor the increase in blood velocity changed in hyperoxia, demonstrating that blood flow did not change. Our results resolve the contradictory findings of Gordon et al. (10), who found a substantial O2 modulation of neurovascular coupling in brain slices, and Lindauer et al. (11), who found no O2 modulation in the cortex in vivo. Oxygen modulates neurovascular coupling in ex vivo preparations because pO2 rises dramatically (from 34 to 548 mm Hg in the retina) when switching from 21% to 100% O2. In contrast, pO2 has been reported to rise only modestly, from ∼21 to ∼53 mm Hg, when switching from normoxic to hyperoxic conditions in vivo (15). Our results (Fig. 6) demonstrate that reproducing this modest rise in pO2 in the ex vivo retina does not result in a change in light-evoked vascular responses. Similar small increases in pO2 have been measured in the brain in vivo during normobaric hyperoxia, where pO2 rises from ∼12–38 mm Hg to ∼55–90 mm Hg (17–21). This modest increase in pO2 likely accounts for why O2 does not alter neurovascular coupling during hyperoxia in vivo. However, pO2 values ranging from ∼50 to 453 mm Hg have been reported during hyperbaric (3 atmospheres) hyperoxia (18, 20), and if these higher values are accurate, then our findings might not explain the lack of O2 modulation reported in the Lindauer study (11).

Although hyperoxia in vivo did not affect functional hyperemia, it did induce a tonic vasoconstriction of retinal arterioles, confirming similar findings reported previously in both humans and animals (25, 26). This increase in vascular tone does not appear to be a systemic response, given that there was no change in arterial blood pressure. The vasoconstriction could be a homeostatic response to maintain a near-constant tissue pO2 in the retina. An increase in vascular tone would decrease the amount of blood flowing through the tissue, and thus the amount of O2 released within the retina. This vascular response may be one reason why retinal pO2 changes so little despite the approximate fourfold increase in arterial pO2 observed during hyperoxia. It would be of interest to examine whether the hyperoxia-induced decrease in resting diameter in vivo is mediated by 20-HETE production.

Oxygen, as well as reactive oxygen species generated in high O2, can modulate many physiological and pathological signaling pathways (27). This is especially true for pathways involving heme proteins (28). The modulatory effects of O2 should be considered when designing ex vivo experiments, and results should be interpreted with caution, especially when tissues are exposed to high O2, resulting in much higher than normal tissue pO2 levels (29). This is true not only for neurovascular studies, but also more broadly for studies involving signaling pathways sensitive to O2 or to reactive oxygen species. For example, neuronal NOS is sensitive to O2 concentration (KmO2 of 350 μM, equivalent to ∼266 mm Hg) (30), and high O2 may alter NO-mediated synaptic regulation in brain slice preparations (31, 32).

In summary, we have demonstrated that O2 can modulate neurovascular coupling by altering arachidonic acid signaling pathways. This effect is robust in the ex vivo retina, in which tissue pO2 rises dramatically under high O2 conditions, but is not apparent in the in vivo retina, in which tissue pO2 rises only modestly, even when animals are breathing 100% O2. Our findings demonstrate that even under hyperoxic conditions often present in the clinic, neurovascular coupling is not diminished in vivo, ensuring an adequate energy supply to active neurons. Similarly, if hyperoxic treatment of premature infants contributes to retinopathy of prematurity, as many studies indicate (12), it is unlikely to be due to a loss of neurovascular coupling. Increased O2 in vivo can influence many physiological and pathological processes, but it does not substantially alter activity-dependent regulation of blood flow.

Materials and Methods

The ex vivo retina and in vivo rat preparations have been described in detail previously (6, 33). All methods were approved by the University of Minnesota's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ex Vivo Retina Experiments.

Preparation.

Retinas were removed from enucleated eyes of male Long–Evans rats (Harlan) and superfused at 2–3 mL/min with Hepes-buffered saline (128 mM NaCl, 3.0 mM KCl, 2.0 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 15.0 mM d-glucose, and 20 mM Hepes; pH 7.4) bubbled with air (21% O2), 28% O2 (balance N2), or 100% O2. Arterioles were preconstricted with the thromboxane analog U-46619 (100 nM) for 10 min or until stable (34). Retinas were imaged with a cooled CCD camera (CoolSnap ES; Roper Scientific) and IR-DIC optics, and data were analyzed using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). Arteriole responses were quantified as the percent change between the largest or smallest vessel diameter measured during stimulation and the average prestimulus resting diameter.

Retinal Stimulation.

For photic stimulation, diffuse flickering white light (250-ms flashes repeated 2 times/s for 60 s) was used. For glial stimulation, retinas were incubated in the Ca2+ indicator dye fluo-4 AM (37.5 μg/mL) and pluronic F-127 (2.6 mg/mL) for 30 min at room temperature. Glial Ca2+ waves were evoked by focal ejection of ATP (200 μM at 10 psi for 200 ms). The ejection site was 100–150 μm in a downstream (superfusion flow) direction from a vessel to avoid any direct effects of ATP on the vessel. The ejection site location was chosen to achieve Ca2+ waves that propagated close to, but did not reach, the vessel of interest. In low O2, this stimulation paradigm resulted in vasomotor responses similar to those produced by light. Glial-evoked vascular responses were obtained from a different vessel for each trial, because glial cells are refractory for Ca2+ signaling. Glial Ca2+ and vessel diameter were imaged concurrently by alternate epifluorescence and IR-DIC imaging.

O2 Measurement.

O2-sensitive microelectrodes (10 μm tip diameter; Unisense) were calibrated before each experiment in 0% and 21% O2-equilibrated saline. Electrodes were advanced into the ex vivo retina at a 45-degree angle. Retinal layers were identified by concurrent IR-DIC imaging, and measurements were made when the electrode tip was centered in each layer. Recordings obtained during electrode insertion closely matched those obtained during electrode retraction, although only the latter were analyzed.

In Vivo Experiments.

Preparation.

Surgery was performed under 2% isoflurane anesthesia. The left femoral vein and artery were cannulated for drug administration and monitoring of blood pressure, respectively, and tracheotomy was performed for artificial ventilation. During the experiments, anesthesia was maintained by infusion of α-chloralose–HBC complex (800 mg/kg bolus; 550 mg/kg/h). Animals were artificially ventilated (30–50 breaths/min) and paralyzed with gallamine triethiodide (20 mg/kg bolus; 20 mg/kg/h) to prevent eye movements. Arterial blood pressure, end-tidal CO2, heart rate, and blood O2 saturation level (through pulse oximetry) were monitored continuously. Blood gas values and pH were evaluated periodically. pH and mean arterial pressure were maintained within physiological limits (7.35–7.45 and 100–125 mm Hg, respectively) by adjusting the ventilation pressure and respiratory rate. During normoxia, inspired O2 concentration was adjusted to maintain arterial pO2 at 110–120 mm Hg. Hyperoxia was induced by increasing inspired O2 to 100%.

Light Stimulation.

The retina was stimulated with a 12-Hz flickering diffuse white light with an illuminance of 12 klux at the surface of the globe (focused through a fiber bundle at a 45-degree angle).

Vascular Response Measurements.

The retina was imaged with an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope. The luminal diameters of first-order arterioles (labeled with an i.v. injection of dextran fluorescein) were measured by confocal line scans. Peak response was calculated as the mean of the three greatest responses. Blood velocity was measured by laser speckle flowmetry (33). Data were analyzed with custom MatLab routines.

Statistics.

Vasomotor responses in the isolated retina were analyzed using a one-tailed Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon rank-sum test for nonnormal distributions. The proportions test was used for binomial data (e.g., whether dilation or constriction occurred) (Figs. 1, 4, and 6). The homoscedastic two-tailed Student t test was used for pO2 measurements ex vivo (Fig. 2). The one-tailed paired t test was used for paired data from the same vessels ex vivo (Fig. 3), and the two-tailed paired t test was used for in vivo data (Table 1 and Fig. 5). In all analyses, α = 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Serge Charpak and Jérôme Lecoq for help with the O2 recordings, David Attwell and Clare Howarth for comments on the manuscript, and Michael Burian for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant EY004077, Fondation Leducq, and a National Institutes of Health Vision Training Grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Roy CS, Sherrington CS. On the regulation of the blood supply of the brain. J Physiol. 1890;11:85–158, 17. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1890.sp000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attwell D, et al. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature. 2010;468:232–243. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zonta M, et al. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:43–50. doi: 10.1038/nn980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulligan SJ, MacVicar BA. Calcium transients in astrocyte endfeet cause cerebrovascular constrictions. Nature. 2004;431:195–199. doi: 10.1038/nature02827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takano T, et al. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:260–267. doi: 10.1038/nn1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metea MR, Newman EA. Glial cells dilate and constrict blood vessels: A mechanism of neurovascular coupling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2862–2870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4048-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkayed NJ, et al. Role of P-450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase in the response of cerebral blood flow to glutamate in rats. Stroke. 1997;28:1066–1072. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.5.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng X, et al. Suppression of cortical functional hyperemia to vibrissal stimulation in the rat by epoxygenase inhibitors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2029–H2037. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01130.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, et al. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid-dependent cerebral vasodilation evoked by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H373–H381. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00745.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon GRJ, Choi HB, Rungta RL, Ellis-Davies GCR, MacVicar BA. Brain metabolism dictates the polarity of astrocyte control over arterioles. Nature. 2008;456:745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature07525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindauer U, et al. Neurovascular coupling in rat brain operates independent of hemoglobin deoxygenation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:757–768. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cringle SJ, Yu DY. Oxygen supply and consumption in the retina: Implications for studies of retinopathy of prematurity. Doc Ophthalmol. 2010;120:99–109. doi: 10.1007/s10633-009-9197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu DY, Cringle SJ, Alder VA, Su EN. Intraretinal oxygen distribution in rats as a function of systemic blood pressure. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H2498–H2507. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.6.H2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harder DR, et al. Identification of a putative microvascular oxygen sensor. Circ Res. 1996;79:54–61. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu DY, Cringle SJ, Alder V, Su EN. Intraretinal oxygen distribution in the rat with graded systemic hyperoxia and hypercapnia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2082–2087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juránek I, Suzuki H, Yamamoto S. Affinities of various mammalian arachidonate lipoxygenases and cyclooxygenases for molecular oxygen as substrate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1436:509–518. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metzger H, Erdmann W, Thews G. Effect of short periods of hypoxia, hyperoxia, and hypercapnia on brain O2 supply. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31:751–759. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Sam AD, Klitzman B, Piantadosi CA. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase on brain oxygenation in anesthetized rats exposed to hyperbaric oxygen. Undersea Hyperb Med. 1995;22:377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Hara JA, et al. Simultaneous measurement of rat brain cortex PtO2 using EPR oximetry and a fluorescence fiberoptic sensor during normoxia and hyperoxia. Physiol Meas. 2005;26:203–213. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/26/3/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamieson D, Vandenbrenk HA. Measurement of oxygen tension in cerebral tissues of rats exposed to high pressures of oxygen. J Appl Physiol. 1963;18:869–876. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1963.18.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cater DB, Garattini S, Marina F, Silver IA. Changes of oxygen tension in brain and somatic tissues induced by vasodilator and vasoconstrictor drugs. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1961;155:136–158. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amruthesh SC, Boerschel MF, McKinney JS, Willoughby KA, Ellis EF. Metabolism of arachidonic acid to epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids, and prostaglandins in cultured rat hippocampal astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1993;61:150–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zonta M, et al. Glutamate-mediated cytosolic calcium oscillations regulate a pulsatile prostaglandin release from cultured rat astrocytes. J Physiol. 2003;553:407–414. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebremedhin D, et al. Production of 20-HETE and its role in autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Circ Res. 2000;87:60–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hickam JB, Frayser R. Studies of the retinal circulation in man: Observations on vessel diameter, arteriovenous oxygen difference, and mean circulation time. Circulation. 1966;33:302–316. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.33.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eperon G, Johnson M, David NJ. The effect of arterial PO2 on relative retinal blood flow in monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol. 1975;14:342–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stogner SW, Payne DK. Oxygen toxicity. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26:1554–1562. doi: 10.1177/106002809202601214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wijayanti N, Katz N, Immenschuh S. Biology of heme in health and disease. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:981–986. doi: 10.2174/0929867043455521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulkey DK, Henderson RA, 3rd, Olson JE, Putnam RW, Dean JB. Oxygen measurements in brain stem slices exposed to normobaric hyperoxia and hyperbaric oxygen. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1887–1899. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abu-Soud HM, Rousseau DL, Stuehr DJ. Nitric oxide binding to the heme of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase links its activity to changes in oxygen tension. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32515–32518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stuehr DJ, Santolini J, Wang ZQ, Wei CC, Adak S. Update on mechanism and catalytic regulation in the NO synthases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36167–36170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elayan IM, Axley MJ, Prasad PV, Ahlers ST, Auker CR. Effect of hyperbaric oxygen treatment on nitric oxide and oxygen free radicals in rat brain. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2022–2029. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srienc AI, Kurth-Nelson ZL, Newman EA. Imaging retinal blood flow with laser speckle flowmetry. Front Neuroenergetics. 2010;2:128. doi: 10.3389/fnene.2010.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Filosa JA, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Calcium dynamics in cortical astrocytes and arterioles during neurovascular coupling. Circ Res. 2004;95:e73–e81. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148636.60732.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]