Abstract

Background

The Door-to-Balloon (D2B) Alliance is a collaborative effort of more than 900 hospitals aimed at improving D2B times for ST–segment elevation myocardial infarction. Although such collaborative efforts are increasingly used to promote improvement, little is known about the types of health care organizations that enroll and their motivations to participate.

Methods

To examine the types of hospitals enrolled and reasons for enrollment, a cross-sectional study was conducted of 915 D2B Alliance hospitals and 654 hospitals that did not join the D2B Alliance. Data were obtained from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey of Hospitals and a Web-based survey completed by 797 enrolled hospitals (response rate, 87%). Chi-square statistics were used to examine statistical associations, and qualitative data analysis was used to characterize reported reasons for enrolling.

Results

Hospitals that enrolled in the D2B Alliance were significantly (p values < .05) more likely to be larger, nonprofit (versus for-profit), and teaching (versus nonteaching) hospitals. Earlier- versus later-enrolling hospitals were more likely to have key recommended strategies already in place at the time of enrollment. Improving quality and “doing the right thing” were commonly reported reasons for enrolling; however, hospitals also reported improving market share, meeting regulatory and accreditation requirements, and enhancing reputation as primary reasons for joining.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the underlying goals of organizations to improve their position in the external environment—including economic, regulatory, accreditation, and professional environments. Designing quality improvement collaborative efforts to appeal to these goals may be an important strategy for enhancing participation and, in turn, increasing the uptake of evidence-based innovations.

Prompt treatment is essential for patients with ST–segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) who are treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1,2 However, recent studies3,4 indicate that only about one third of hospitals achieve national recommendations5 for door-to-balloon (D2B) times of ≤90 minutes. Several key hospital strategies are strongly associated with more rapid D2B times for patients undergoing primary PCI for STEMI3,6–15; nevertheless, only a minority of hospitals have implemented these strategies.3

To speed the adoption of evidence-based strategies to reduce D2B times, in 2006 the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in partnership with 38 other organizations created D2B: An Alliance for Quality (http://www.d2balliance.org).16 The focus of the effort was on hospitals in the United States, although hospitals elsewhere may also enroll. The goal of the D2B Alliance was for each participating hospital to achieve D2B times of 90 minutes or less for at least 75% of nontransfer patients with STEMI through the implementation of evidence-based strategies. These strategies included emergency medicine activation of the catheterization laboratory, catheterization laboratory activation with a single call, explicit expectations of staff arrival within 20–30 minutes of page, prompt data feedback, senior management support, a team-based approach, and activation of the catheterization laboratory on the basis of prehospital electrocardiogram (ECG) results while the patient is still en route to the hospital (an optional strategy).

Participating hospitals gained access to an online tool kit and change package to facilitate adoption of the recommended strategies, a hospital-specific action plan for improvement, Web-based seminars focused on implementing new practices, and an online community to foster interorganizational learning and communication.

Although many studies have documented the variable adoption of evidence-based strategies to improve quality of care,17–22 we know little about which health care organizations choose to enroll in quality improvement (QI) collaborative efforts and why hospitals are motivated to participate in such efforts. With greater use of national collaborative efforts as models for promoting hospital performance improvement,23–26 understanding hospital motivations to engage in such collaborative efforts is essential for the success of these initiatives. Given its large enrollment in a relatively short period, the D2B Alliance experience provides an ideal opportunity to investigate reported hospital motivations to join such large-scale collaborative efforts to improve quality.

Methods

Setting: The D2B Alliance

The D2B Alliance, an international QI collaborative effort, included extensive development and recruitment phases. On the basis of a detailed review of published empirical evidence,27 the D2B Alliance Workgroup created a change package and tool kit to be used as instruction and guidance manuals for enrolled hospitals. The D2B Alliance Web site and formal launch at the American Heart Association scientific sessions were initiated in late October 2006.

Study Design and Sample

We conducted a cross-sectional Web-based survey of the 915 hospitals (of approximately 1,400 hospitals that perform PCI for patients with STEMI) that joined the D2B Alliance during the nine-month enrollment period (October 2006–June 2007). Respondents included QI directors, nurse managers, catheterization laboratory directors, emergency department directors, emergency medicine physicians, cardiologists, and a range of clinical managers. Of the 915 hospitals enrolled in the D2B Alliance, 797 (87%) completed the survey. All survey responses were identified by code, and the respondent and hospital names were separated from the data for all analyses. All research procedures were approved by the Human Investigation Committee at Yale University School of Medicine.

Data and Measures

Data regarding hospital characteristics including number of staffed beds, ownership type (nonprofit, for-profit, governmental), geographical location (in the nine Census regions), and teaching status (where teaching hospital was defined as one with a residency program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) were obtained from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals, 2004 (1998 data).28 Data regarding primary reasons for enrollment were measured using open-ended responses to the Web-based survey item “What was the primary reason for your hospital enrolling in the D2B Alliance?” In addition, the Web-based survey asked hospitals a set of closed-ended questions regarding their current processes for treating patients with STEMI, with a focus on the recommended strategies.

Data Analysis

To determine the statistical association between hospital characteristics and the likelihood and timing of enrolling in the D2B Alliance, we used chi-square and t-test statistics as appropriate. The 1,420 hospitals with primary PCI capability included all those that had submitted D2B time data to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR™) of the ACC or the Health Quality Alliance (HQA) in 2005. We telephoned hospitals reporting fewer than 15 cases to the HQA in 2005 to verify primary PCI capacity and to exclude potential errors due to HQA reporting. Using this list of PCI hospitals, we compared hospitals that had enrolled with the D2B Alliance with hospitals that had not enrolled. Because our list of PCI hospitals was based on 2005 data, we were unable to match 44 hospitals that were enrolled in the D2B Alliance to the PCI hospital list. Telephone verification indicated that the majority of the 44 hospitals had begun their PCI programs after 2005. Our analysis compared the 753 hospitals that were enrolled with the D2B Alliance (and performing primary PCI as of 2005) with 656 hospitals that were not enrolled with the D2B Alliance but were performing primary PCI as of 2005. All analyses were completed using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS, Inc.; Cary, North Carolina).

To characterize the primary reasons for enrollment on the basis of textual responses to the open-ended survey question, three researchers [E.H.B., E.J.C., E.L.L.] first independently conducted line-by-line reviews of all responses and developed categories of like responses. Then the researchers [E.H.B., E.J.C., E.L.L., A.F.S., A.G.N., H.M.K.] met to review and discuss common categories. From this discussion, a coding structure was developed to encompass the breadth of reasons provided by hospitals. With this final code structure, the three researchers again independently reviewed and coded responses. Agreement among the coders was excellent, with the same code independently assigned to the same text in 87% of cases. Remaining differences were resolved by negotiated consensus. Qualitative analyses were accomplished using ATLAS.ti, version 5.2.9 (Scientific Software Development GmbH; Berlin).

Results

Pattern of Hospital Enrollment in the D2B Alliance

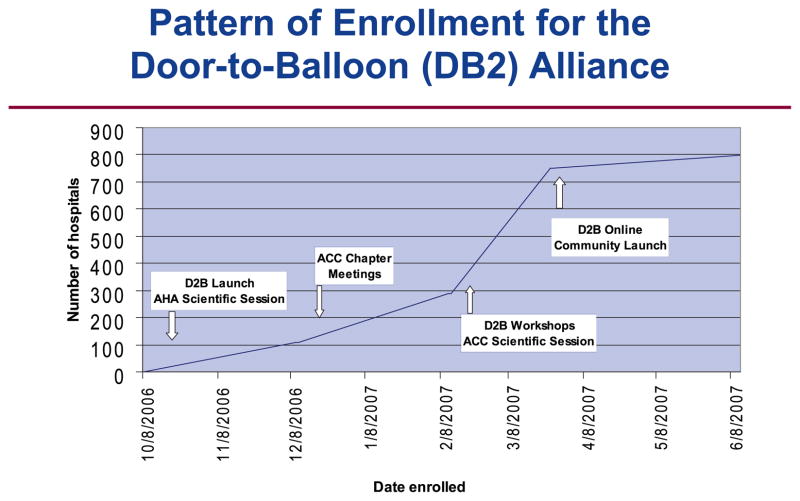

The characteristics of the 797 hospitals enrolled in the D2B Alliance and differences with PCI hospitals that did not enroll in the D2B Alliance are displayed in Table 1 (above) and Table 2 (page 96). The pattern of hospital enrollment in the D2B Alliance is shown in Figure 1 (right). The first approximate quartile (n = 200) of hospitals joined within 4.5 months of the initial launch. After this initial slow start, the pace of enrollment accelerated, with an additional 200 hospitals joining within the following month, at which point the ACC announced that only hospitals that enrolled by the end of March would be included in the Web announcement identifying hospital participants in the D2B Alliance. An additional 200 hospitals joined within the following two weeks, and by six months after the initial launch (end of March 2007), 600 hospitals had enrolled. The final hospitals joined in the last two months of the enrollment period.

Table 1.

Hospitals That Enrolled in the Door-to-Balloon Alliance (N = 797)

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Beds | ||

| <300 | 342 | 42.9 |

| 300–600 | 335 | 42.0 |

| >600 | 100 | 12.5 |

| Unknown | 20 | 2.5 |

| Mean | 376 | — |

| Ownership Type | ||

| Nonprofit | 575 | 72.1 |

| For-profit | 124 | 15.6 |

| Governmental | 78 | 1.3 |

| Unknown | 20 | 2.5 |

| Census Region | ||

| New England | 29 | 3.6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 92 | 11.5 |

| South Atlantic | 143 | 17.9 |

| East North Central | 161 | 20.2 |

| East South Central | 66 | 8.3 |

| West North Central | 54 | 6.8 |

| West South Central | 97 | 12.2 |

| Mountain | 53 | 6.6 |

| Pacific | 82 | 10.3 |

| Unknown | 20 | 2.5 |

| Teaching Status | ||

| Teaching hospital | 418 | 52.4 |

| Nonteaching hospital | 359 | 45.0 |

| Unknown | 20 | 2.5 |

Table 2.

Hospitals That Enrolled and Did Not Enroll in the Door-to-Balloon (D2B) Alliance Among Hospitals in the United States That Perform Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention*

| Characteristic | Enrolled hospitals (N = 753*) | Non-enrolled hospitals (N = 654) | Odds Ratio (95% C.I.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Beds | |||

| < 300 | 324 | 416 | reference |

| 300–600 | 329 | 193 | 2.19 (1.74, 2.75) |

| > 600 | 100 | 45 | 2.85 (1.95, 4.17) |

| Ownership Type | |||

| For-profit | 119 | 140 | reference |

| Nonprofit | 556 | 434 | 1.51 (1.15, 1.98) |

| Governmental | 78 | 80 | 1.15 (0.77, 1.71) |

| Census Region | |||

| New England | 28 | 22 | reference |

| Mid-Atlantic | 89 | 68 | 1.03 (0.54, 1.95) |

| South Atlantic | 137 | 65 | 1.66 (0.88, 3.11) |

| East North Central | 154 | 100 | 1.21 (0.66, 2.23) |

| East South Central | 66 | 43 | 1.21 (0.61, 2.38) |

| West North Central | 53 | 62 | 0.67 (0.34, 1.31) |

| West South Central | 96 | 115 | 0.66 (0.35, 1.22) |

| Mountain | 51 | 63 | 0.64 (0.33, 1.24) |

| Pacific | 79 | 108 | 0.58 (0.31, 1.08) |

| Unknown | 8 | † | |

| Teaching Status | |||

| Nonteaching hospital | 358 | 226 | reference |

| Teaching hospital | 395 | 428 | 1.72 (1.38, 2.13) |

Included D2B Alliance hospitals that could be matched with the list of PCI hospitals, derived from the 2005 Health Quality Alliance and National Cardiovascular Data Registry™. C.I., confidence interval.

The model was run without the hospitals for which census region data were not available.

Figure 1.

The pattern of enrollment during the nine-month DB2 enrollment period is shown. AHA, American Hospital Association; ACC, American College of Cardiology.

Earlier Versus Later Hospital Enrollees

Hospitals that enrolled earlier were significantly larger, more likely to be nonprofit, more likely to be nonteaching hospitals, and varied in geographical location (overall chi-square p values, < .01). Compared with hospitals that enrolled later, hospitals that enrolled earlier were more likely to report that they already had emergency medicine activation, activation with a single call, prompt data feedback, and use of pre-hospital electrocardiograms to activate the catheterization laboratory (overall chi-square p values < .01; Table 3, page 97). There was no apparent pattern regarding the reported reasons for enrolling and the timing of enrollment.

Table 3.

Prevalence Rates of Recommended Strategies for Hospitals by Timing of Enrollment with the Door-to-Balloon Alliance

| Recommended Strategy | First Set of Hospitals (n = 200) | Second Set of Hospitals (n = 200) | Third Set of Hospitals (n = 200) | Last Set of Hospitals (n = 197) | Overall Chi-Square P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Emergency medicine activates the catheterization laboratory. | |||||||||

| Yes | 114 | 57.0 | 93 | 46.5 | 90 | 45.0 | 77 | 39.1 | .010 |

| No | 80 | 40.0 | 101 | 50.5 | 100 | 50.0 | 106 | 53.8 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 3.0 | 6 | 3.0 | 10 | 5.0 | 14 | 7.1 | |

| One call actives the catheterization laboratory. | |||||||||

| Yes | 66 | 33.0 | 59 | 29.5 | 42 | 21.0 | 38 | 19.3 | .008 |

| No | 134 | 67.0 | 141 | 70.5 | 158 | 79.0 | 159 | 80.7 | |

| Catheterization laboratory team is ready within 20–30 minutes of initial page. | |||||||||

| Yes | 160 | 80.0 | 158 | 79.0 | 150 | 75.0 | 139 | 70.6 | .411 |

| No | 34 | 17.0 | 32 | 16.0 | 31 | 15.5 | 41 | 20.8 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 3.0 | 10 | 5.0 | 19 | 9.5 | 17 | 8.6 | |

| Prompt data feedback is given (within 1 week). | |||||||||

| Yes | 126 | 63.0 | 105 | 52.5 | 83 | 41.5 | 95 | 48.2 | .002 |

| No | 55 | 27.5 | 62 | 31.0 | 83 | 41.5 | 67 | 34.0 | |

| Unknown | 19 | 9.5 | 33 | 16.5 | 34 | 17.0 | 35 | 17.8 | |

| Pre-hospital electrocardiogram is used to activate the catheterization laboratory. | |||||||||

| Yes | 68 | 34.0 | 56 | 28.0 | 47 | 23.5 | 46 | 23.4 | .094 |

| No | 125 | 62.5 | 131 | 65.5 | 138 | 69.0 | 135 | 68.5 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 3.0 | 13 | 6.5 | 15 | 7.5 | 16 | 8.1 | |

Reasons for Enrolling in the D2B Alliance

Improving Quality

The most commonly stated reason for enrolling in the D2B Alliance was to improve quality of patient care:

The goal of 90 minutes door-to-reperfusion time is the primary factor in our participation with the D2B Alliance. Our hospital continually strives for performance improvement within the organization and promotes an environment of clinical excellence. (Hospital 394)

Specific Interventions Provided by the D2B Alliance

Several hospitals noted that the access to specific tool kits, data feedback forms and processes, and strategies for organizational change were primary reasons for their enrolling with the D2B Alliance. In addition, hospitals noted value in networking with and benchmarking against other D2B Alliance hospitals as motivation for enrolling. Finally, some hospitals reported that joining the D2B Alliance raised the visibility and perceived importance of D2B time within the hospital, which in turn facilitated their improvement efforts. Illustrating this latter reason, a hospital stated:

Our joining the D2B Alliance keeps the light shining on this initiative and sustains the gains we have achieved thus far. The D2B Alliance keeps everyone engaged in this improvement process. (Hospital 781)

Market Share and Reimbursement

Hospitals also reported that perceived economic benefits such as maintaining the hospital’s competitiveness, gaining market share, or improving reimbursement were a primary reason for joining the D2B Alliance:

We desire to consistently achieve D2B times below 90 minutes and enhance marketability for referrals from surrounding small hospitals. (Hospital 140)

Joining the D2B Alliance helps with the potential loss of business to competitors. (Hospital 560)

In addition, some hospitals mentioned enhanced reimbursement specifically as a motivation to enroll in the D2B Alliance. These hospitals recognized the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pay-for-performance initiatives as well as programs with other large private payers that provided reimbursement for higher quality as opportunities to receive increased revenues by meeting D2B guidelines:

Quality indicators like door-to-balloon time will be made public and will affect reimbursement to the hospital. (Hospital 189)

Regulatory and Accreditation Requirements

An additional motivation to enroll in the D2B Alliance was to enhance compliance with requirements from payers and accrediting agencies. Hospitals noted the public reporting requirements by CMS and other agencies that contracted with the hospital:

This [door-to-balloon time improvement] is a future requirement for the [payer name] contract we have. (Hospital 66)

We are recently building a Chest Pain Center area seeking accreditation for the emergency transfer of STEMI patients and want the best quality of care for our patients, which we feel the D2B Alliance [helps us] provide. (Hospital 603)

The D2B Alliance will help us comply with the JCAHO and medical insurance companies’ best practices [requirements].” (Hospital 612)

Reputation and Prestige

Some hospital respondents stated that their primary reason for participating was the desire to enhance the reputation of the hospital as a leader in cardiac care and a high-quality provider for patients:

We wanted recognition for already having these initiatives in place. (Hospital 318)

We want to be recognized as the “Heart Center of Choice” for our community. (Hospital 581)

Some hospitals explicitly reported that pressure from peers motivated their hospitals to join. Illustrating this view, hospitals gave these reasons for joining:

Peer pressure, plain and simple. (Hospital 434)

Other local hospitals are doing it. (Hospital 204)

Hospitals also described prestige that might be associated with a widespread campaign on quality and with the ACC:

We wanted to be associated with the ACC.” (Hospital 600)

A primary reason for enrolling was the publicity of having our hospital named in the ACC announcement of D2B hospitals. (Hospital 88)

“It’s the Right Thing to Do”

Several hospitals responded to the survey question about why they joined the D2B Alliance with the phrase “It’s the right thing to do.” Unlike statements related to the external pressures of the market, regulators, accreditors, or peers, this motivation reflected responsiveness to another calling to do the right thing for patients:

It is the right thing to do for our patients. The D2B Alliance is an excellent performance improvement resource. (Hospital 497)

Quality—it is the right thing to do. (Hospital 372)

Discussion

We found diverse motivations for why hospitals participated in the D2B Alliance. Some hospitals were motivated by the belief that being a D2B Alliance hospital would position the organization more favorably in the marketplace or regulatory environment. Other hospitals reported joining the D2B Alliance to improve their prestige and reputation as a high-quality hospital as perceived by both professional peers and the community. Finally, some hospitals reported that they joined the D2B Alliance because it was the “right thing to do” for patients.

Our findings also revealed patterns about the types of hospitals that enrolled in the D2B Alliance. Although the D2B Alliance enrollment consisted of a diverse set of hospitals, larger, teaching, and nonprofit institutions were significantly more likely to enroll. We also found that different types of hospitals enrolled at different times. Hospitals that enrolled earlier tended to be larger, nonteaching, nonprofit, and in certain geographic regions. Furthermore, the hospitals that enrolled earlier reported greater use of the recommended strategies already in place at the time of enrollment than the hospitals that enrolled later.

The pattern of D2B Alliance enrollment is consistent with the S-curve that has been used to characterize the diffusion of innovations,17,29 in which new practices or ideas are adopted slowly at first—traditionally by opinion leaders and change agents17,29–33—followed by substantial acceleration and finally leveling off of adoption rates. Paradoxically, the hospitals that enrolled earlier may have had less need for the tool kit and change package of the D2B Alliance; the early enrolling hospitals were more likely to report that the recommended strategies were already in place at the time of enrollment. Nonetheless, consistent with the literature on innovation and diffusion,18,29 these early enrollees, who may be thought of as expert users or opinion leaders, can play an essential role in fostering more widespread adoption of new practices for other organizations participating in such QI collaborative efforts. Moreover, even hospitals that joined the D2B Alliance early had opportunities to improve.

The study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. The data are self-reported by a single person in each hospital. Although the respondents were generally those who were most familiar with the D2B Alliance in their hospitals, views on why a hospital enrolled likely differ across staff. Furthermore, in some cases respondents may not have wanted to reveal underlying reasons for joining, particularly if enrollment was in response to significant adverse events or quality problems. Finally, the study is descriptive, and therefore we were not able to identify predictors of strategy implementation or engagement in the D2B Alliance.

Our findings have several implications. First, even with an initiative that was supported by professional societies and many partners, had strong local support in many states, and ultimately enrolled more than 900 hospitals, the initial enrollment was relatively slow. Researchers, policymakers, and funding agencies that support such collaborative QI efforts might therefore anticipate that accomplishing the spread of such initiatives requires substantial time. However, certain tactics, such as positive media recognition for participation, can accelerate enrollment. Second, the experience in the D2B Alliance suggests that selection effects may be substantial; enrolling hospitals differed significantly from nonenrolling hospitals in key characteristics that have been shown in the literature34–36 to be associated with higher quality. These findings highlight the need to carefully adjust for selection effects when evaluating the impact of such initiatives. Third, collaborative QI efforts may be challenged by the fact that the earliest enrolling hospitals may already have recommended practices in place. Identifying ways to attract organizations that are most in need of improvement but may have limited infrastructure to facilitate engagement in such efforts is an important challenge. Finally, our findings suggest that strategies to enroll organizations in QI initiatives will be most successful if they appeal to multiple goals in addition to the goal of improving quality. Communicating the benefits of participation in terms of market position, regulatory requirements, or professional prestige is likely to promote additional enrollment by health care organizations.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the American College of Cardiology, Washington, DC, and, in part, by the Commonwealth Fund, New York City. Drs. Krumholz and Bradley were supported, in part, by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, MD, grant #R01HL072575. Dr. Bradley is supported by the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation in Hartford, Connecticut, grant #02-102. Mr. Nazem is supported by the Yale University School of Medicine Medical Student Research Fellowship and the Richard Alan Hirshfield Memorial Fellowship in New Haven, Connecticut. None of the sponsors had a role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge Mr. Gregory Mulvey for his outstanding research assistance.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth H. Bradley, Professor of Public Health and Director of the Health Management Program, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, and a member of The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety’s Editorial Advisory Board

Brahmajee K. Nallamothu, Investigator, Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence, Ann Arbor VA Medical Center, and Assistant Professor, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Amy F. Stern, Formerly Associate Director, Quality Alliances, American College of Cardiology, Washington, DC, is Senior Director, National Priorities Outreach Efforts, National Quality Forum, Washington, DC

Emily J. Cherlin, Research Associate, Section of Health Policy and Administration, Yale University School of Medicine

Yongfei Wang, Lecturer, Section of Cardiovascular Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine

Jason R. Byrd, Formerly Associate Director, Quality Improvement, American College of Cardiology, Washington, DC, is Associate Director of Practice Management and Quality Initiatives, American Society of Anesthesiologists, Washington, DC

Erika L. Linnander, Formerly Project Manager, Yale University School of Medicine, is Administrative Fellow, The Johns Hopkins Health System, Baltimore

Alexander G. Nazem, A Medical Student, Yale University School of Medicine

John E. Brush, Jr., Physician, Sentara Cardiovascular Research Institute, Norfolk, Virginia

Harlan M. Krumholz, Director, Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Haven; Harold H. Hines Jr., Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology and Public Health; and Director, Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program, Yale University School of Medicine

References

- 1.Berger PB, et al. Relationship between delay in performing direct coronary angioplasty and early clinical outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction: Results from the Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes (GUSTO-IIb) trial. Circulation. 1999 Jul 6;100:14–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon CP, et al. Relationship of symptom-onset-to-balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000 Jun 14;283:2941–2947. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.22.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley EH, et al. Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 30;355:2308–2320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNamara RL, et al. Hospital improvement in time to reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction, 1999 to 2002. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Jan 3;47:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Aug 4;44:E1–E211. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canto JG, et al. The prehospital electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction: Is its full potential being realized? National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Mar 1;29:498–505. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caputo RP, et al. Effect of continuous quality improvement analysis on the delivery of primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1997 May 1;79:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis JP, et al. The pre-hospital electrocardiogram and time to reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction, 2000–2002: Findings from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction-4. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Apr 18;47:1544–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross BW, et al. An approach to shorten time to infarct artery patency in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2007 May 15;99:1360–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacoby J, et al. Cardiac cath lab activation by the emergency physician without prior consultation decreases door-to-balloon time. J Invasive Cardiol. 2005 Mar;17:154–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swor R, et al. Prehospital 12-lead ECG: Efficacy or effectiveness? Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006 Jul–Sep;10:374–377. doi: 10.1080/10903120600725876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thatcher JL, et al. Improved efficiency in acute myocardial infarction care through commitment to emergency department–initiated primary PCI. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003 Dec;15:693–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Loo A, et al. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: Direct transportation to catheterization laboratory by emergency teams reduces door-to-balloon time. Clin Cardiol. 2006 Mar;29:112–116. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960290306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward MR, et al. Effect of audit on door-to-inflation times in primary angioplasty/stenting for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001 Feb 1;87:336–338. A339. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarich SW, et al. Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary quality improvement initiative in reducing door-to-balloon times in primary angioplasty. J Interv Cardiol. 2004 Aug;17:191–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2004.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krumholz HM, et al. A campaign to improve the timeliness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention: Door-to-Balloon: an alliance for quality. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2008 Feb;1:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003 Apr 16;289:1969–1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradley EH, et al. Patterns of diffusion of evidence-based clinical programmes: A case study of the Hospital Elder Life Program. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Oct;15:334–338. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.018820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumholz HM, et al. Aspirin for secondary prevention after acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: Prescribed use and outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1996 Feb 1;124:292–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-3-199602010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krumholz HM, et al. Aspirin in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in elderly Medicare beneficiaries: Patterns of use and outcomes. Circulation. 1995 Nov 15;92:2841–2847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krumholz HM, et al. National use and effectiveness of beta-blockers for the treatment of elderly patients after acute myocardial infarction: National Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA. 1998 Aug 19;280:623–629. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGlynn EA, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jun 26;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ. 1996 Mar 9;312:619–622. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7031.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berwick DM, et al. The 100,000 lives campaign: Setting a goal and a deadline for improving health care quality. JAMA. 2006 Jan 18;295:324–327. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holman WL, et al. Alabama coronary artery bypass grafting project: Results of a statewide quality improvement initiative. JAMA. 2001 Jun 20;285:3003–3010. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta RH, et al. Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: The Guidelines Applied in Practice (GAP) initiative. JAMA. 2002 Mar 13;287:1269–1276. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradley EH, et al. Summary of evidence regarding hospital strategies to reduce door-to-balloon times for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007 Sept;6:91–97. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e31812da7bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey Database 2004. Chicago: AHA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers EM. Diffusions of Innovations. 5. New York City: Free Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradley EH, et al. Translating research into practice: Speeding the adoption of innovative health care programs. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2004 Jul 12;:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eagle KA, et al. Closing the gap between science and practice: The need for professional leadership. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003 Mar–Apr;22:196–201. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gladwell M. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Make a Big Difference. 1. Boston: Little, Brown; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soumerai SB, et al. Effect of local medical opinion leaders on quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998 May 6;279:1358–1363. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allison JJ, et al. Relationship of hospital teaching status with quality of care and mortality for Medicare patients with acute MI. JAMA. 2000 Sep 13;284:1256–1262. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayanian JZ, et al. Teaching hospitals and quality of care: A review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2002 Sep;80:569–593. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polanczyk CA, et al. Hospital outcomes in major teaching, minor teaching, and nonteaching hospitals in New York state. Am J Med. 2002 Mar;112:255–261. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]