Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Stress cardiomyopathy is a cardiac syndrome that is characterized by transient left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. Its epidemiology has been described in homogeneous Asian, Caucasian and Black populations, but its characteristics in heterogeneous populations are poorly understood. Our aim was to assess the characteristics of stress cardiomyopathy in a heterogeneous population that included a large percentage of Hispanics.

METHODS:

We reviewed 59 consecutive cases of stress cardiomyopathy that were confirmed by coronary angiography and were in agreement with the Mayo Clinic diagnostic criteria.

RESULTS:

The mean age of the patients was 74 years (range, 39-91 years), and 37 patients were female (62.7%). Twenty-nine patients (49.2%) were Latino/Hispanic, 26 (44%) were Caucasian, 3 (5%) were Asian, and 1 patient (1.7%) was Black. The most common chief symptom was dyspnea, followed by chest pain and an absence of symptoms in 54.2, 28.8, and 18.6% of the patients, respectively. The primary EKG abnormalities consisted of a T wave inversion, an ST segment elevation, and ST segment depression in 69.5%, 25.4%, and 15.3% of the patients, respectively. The stressor event was identified in 90% of the cases. In 32 cases (54%), the stressor event was physical stress or a medical illness, and in 21 cases (35.6%), the stressor event was emotional stress. The in-hospital mortality rate was 8.5%.

CONCLUSIONS:

In our heterogeneous study population, stress cardiomyopathy presented with a 3:2 female-to-male ratio, and dyspnea was the most common chief complaint. Stress cardiomyopathy exhibited a T wave inversion as the primary EKG abnormality. These findings differ from previous cases that have been reported, and further studies are needed.

Keywords: Stress, Cardiomyopathy, Takotsubo, Hispanics, Epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Stress cardiomyopathy (SC) or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a cardiac syndrome that is characterized by transient, left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the apical portion and hyperkinesia in the basal segments with an absence of obstructive coronary artery disease.1 SC was first described in 1990 by Sato et al.,2 who introduced the term “takotsubo”, the Japanese word for “octopus trap”, which has a similar shape as the ballooned apex in cardiac systole. Clinically, SC typically affects women who are in their seventh decade of life and who have had physical or emotional stress; the most common symptom is chest pain. The electrocardiographic changes suggest an acute coronary syndrome (more specifically, an ST segment elevation myocardial infarction). Usually, the cardiac biomarkers are elevated, and multiple wall motion abnormalities with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (as determined by angiography) are hallmarks of this syndrome.1-5

Following its original description, several SC case series have been published from Eastern countries, suggesting that the syndrome affects mostly Asian patients.1-5 More recently, other authors have reported SC in Caucasian6-12 and Black13,14 populations in Europe and North America. No series that included Hispanics has been reported.

Miami Beach, Florida, USA, is an ethnically heterogeneous region, and the reported population is composed primarily of Hispanics (53% in 2006) and Caucasians.15 Our aim was to study the demographic data, clinical characteristics, and in-hospital prognoses of patients with SC in the Miami Beach population.

METHODS

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board, we retrospectively reviewed 76 consecutive cases of presumed acute coronary syndrome who underwent coronary angiograms and were found to lack obstructive coronary disease at our institution from June 2005 through July 2010.

Inclusion criteria

The selected patients satisfied the Mayo Clinic criteria13 for the diagnosis of SC as follows: (1) transient akinesis or dyskinesis in the left ventricular apical and mid-ventricular segments with regional wall motion abnormalities extending beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; (2) the absence of obstructive coronary disease or angiographic evidence of an acute plaque rupture; (3) new electrocardiographic abnormalities (either ST segment elevation or T wave inversion); and (4) the absence of recent significant head trauma, intracranial bleeding, pheochromocytoma, obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease, myocarditis or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients with borderline obstructive coronary artery disease (as determined by angiographic evidence of 50-70% stenosis in at least one epicardial vessel that was associated with the affected wall motion abnormality), patients with unresolved wall motion abnormalities, and patients without a follow-up echocardiogram to reassess left ventricular function.

Data revision

The demographic data, medical history, cardiac biomarkers, 12-lead electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, coronary angiogram and ventriculogram findings, time of the event, and discharge summaries were reviewed.

Ethnicity definitions

The patients were categorized as Caucasian, Hispanic, Black or Asian. The patients were considered of Hispanic origin if they were born in any Central or South American country or any Caribbean country with Hispanic colonization. The white patients were considered to be Caucasian if they did not meet criteria for Hispanic ethnicity. The Black patients were not considered Hispanic regardless of their country of birth. Any immediate descendants from two Asian parents were not considered to be Hispanic, regardless of the country of birth.

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables with normal distributions were analyzed using Student's t-test and are presented as mean +/- 1 standard deviation. The categorical data are presented as percentages and frequencies and were analyzed using the X2 test. A univariate analysis was performed to compare the Hispanics and non-Hispanics, and the variables with p<0.2 were analyzed using multivariate analyses. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Institute, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

We initially evaluated 76 cases, of which 17 were excluded due to the presence of at least one exclusion criterion. Therefore, we analyzed 59 consecutive cases of SC.

Demographics

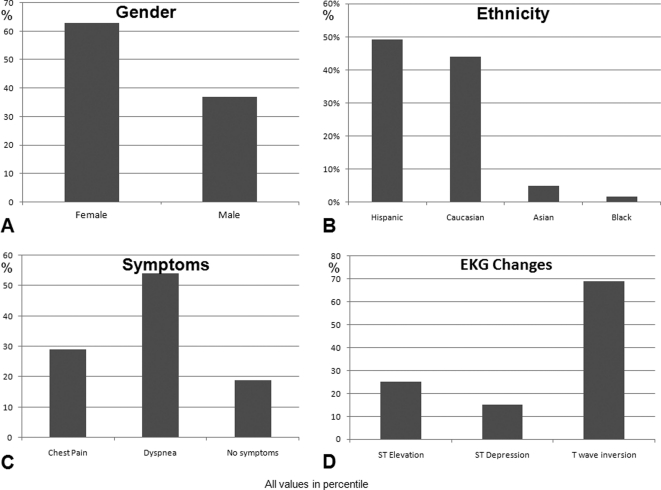

The mean age of the 59 patients was 74 years (range, 39-91 years), and 37 patients were female (62.7%). Twenty-nine patients (49.2%) were Hispanic, 26 patients (44%) were Caucasian, 3 patients (5%) were Asian, and 1 patient (1.7%) was Black (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1.

The gender (A) and ethnic (B) distributions, chief complaints (C) and electrocardiographic findings (D) of the patients presenting with stress cardiomyopathy.

Symptoms

The most prevalent chief symptom was dyspnea, which was followed in prevalence by chest pain and finally the absence of symptoms in 54.2, 28.8, and 18.6% of the patients (Figure 1C). Of the patients who were classified as asymptomatic, 2 (3.4%) presented with cardiac arrest. In 1 patient (1.7%), it was impossible to determine the chief complaint, and both symptoms were considered.

Electrocardiography

Fifty-four patients (91.5%) exhibited electrocardiographic abnormalities, and some cases had overlapping findings. The remaining 5 cases (8.5%) had pacemaker rhythms that precluded further analysis. The primary abnormalities were T wave inversion (TWI), ST segment elevation, and ST segment depression in 69.5, 25.4, and 15.3% of the cases, respectively (Figure 1D).

Cardiac biomarkers and echocardiographic findings

Troponin I levels were elevated in 91.5% of the cases, with a mean of 7.6±18 mg/dL. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction at the time of presentation was 30±9%, and this subsequently improved to 56±9% during a mean follow-up evaluation of 10 days. Reverse Takotsubo, a variant of stress cardiomyopathy that consists of basal hypokinesis with normal apical contractions, occurred in two patients (3.4%).

Trigger event

The stressor event was identified in 90% of the cases. In 32 (54%) of the cases, the stressor event was physical stress or a medical illness, and in 21 (35.6%) of the cases, the stressor event was emotional stress.

Recurrence and mortality rates

The syndrome recurred in two patients (3.4%) during the time frame of our study, and one patient experienced two recurrences. The in-hospital mortality rate was 8.5% (five cases), and all of these deaths were non-cardiac-related. The demographic data, clinical presentations, diagnostic data and in-hospital mortality rates are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of 59 patients in the Stress Cardiomyopathy Registry.

| Total | n = 59 | % |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 37 | 62.7 |

| Male | 22 | 37.3 |

| Age (mean±SD) | 74±13 | |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 29 | 49.2 |

| Non-Hispanic | 30 | 50.6 |

| Caucasian | 26 | 44 |

| Asian | 3 | 5 |

| Black | 1 | 1.7 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Chest pain | 17 | 28.8 |

| Dyspnea | 32 | 54.2 |

| No symptoms | 11 | 18.6 |

| EKG findings | ||

| Abnormal | 54 | 91.5 |

| ST elevation | 15 | 25.4 |

| ST depression | 9 | 15.3 |

| T wave inversion | 41 | 69.5 |

| Troponin I | ||

| Elevated | 54 | 91.5 |

| Not elevated | 5 | 8.5 |

| Peak (mean±SD) | 7.6±18 | |

| Ejection fraction | ||

| Initial (mean±SD) | 30±9.3 | |

| Final (mean±SD) | 56±9 | |

| Trigger event | ||

| Emotional | 21 | 35.6 |

| Physical | 32 | 54 |

| Unidentifiable | 6 | 10 |

| Reverse Takotsubo | 2 | 3.4 |

| Recurrence | 2 | 3.4 |

| Death | ||

| Any cause | 5 | 8.5 |

Ethnic differences

We compared the characteristics of the Hispanics and non-Hispanics using Student's t-test and the X2 test for the continuous and categorical variables, respectively (Table 2). For further evaluation, we performed a univariate analysis that included age, gender, symptoms upon arrival (e.g., chest pain, shortness of breath and arrest), EKG presentation (ST elevation or depressed or inverted T waves), troponin I peak, the trigger (psychological or physical) and in-hospital death. ST elevation and in-hospital death emerged as potentially significant variables (p = 0.019 and p = 0.154, respectively); however, only the presentation of ST elevation in Hispanics reached statistical significance in the multivariate analysis (OR 4.06, 95% CI = 1.22-13.59, p = 0.022).

Table 2.

The demographic and clinical data of the Hispanic and non-Hispanic groups.

| Hispanic(n = 29) | Non-Hispanic (n = 30) | p-value | |

| Age | 74.2+/-15.4 | 73.9+/-12.2 | 0.40 |

| Female | 17 (59%) | 20 (67%) | 0.52 |

| Chest Pain | 8 (28%) | 9 (30%) | 0.84 |

| Dyspnea | 17 (59%) | 14 (47%) | 0.36 |

| Arrest | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 0.98 |

| ST Segment Elevation | 13 (45%) | 5 (17%) | 0.02 |

| ST Segment Depression | 5 (17%) | 4 (13%) | 0.68 |

| T wave Inversion | 19 (66%) | 22 (73%) | 0.51 |

| Peak Troponin | 9.97+/-25.1 | 4.9+/-8.8 | 0.31 |

| Psychological Stress | 10 (34%) | 11 (37%) | 0.86 |

| Physical Stress | 15 (52%) | 17 (57%) | 0.70 |

| Death | 4 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 0.15 |

DISCUSSION

The demographic and clinical characteristics of SC have been documented extensively by several studies of Asian,1-5 Caucasian6-12 and Black13-14 patients within mostly homogeneous populations. Stress cardiomyopathy accounts for 1.7-2.2% of all patients who are admitted with a presumed diagnosis of an acute coronary syndrome.6,16 SC is more commonly described in women (90%) who are older than 70 years of age and who have experienced physical and/or emotional stress, including an acute medical illness. Clinically, the most common presenting symptoms are chest pain (63-90%) and shortness of breath (16-24%). SC is associated with electrocardiographic changes that resemble an acute coronary syndrome, specifically, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (67-75%), with troponin being elevated in approximately 70% of the cases.1-14,16,17

Our data demonstrate some findings that are similar to previous case studies. However, the Miami Beach population exhibited some minor differences. Although the mean age was 74 years old, three of the patients were pre-menopausal women. There was a female predominance of 62.7% in our population, which is lower than what is usually reported. Our gender distribution (an approximately 3:2 female:male ratio) differs markedly from the 9:1 ratio that is described in the majority of reports. It is unclear why our study contained such a relatively high prevalence of men, given a similar gender distribution in the community.

In addition, as expected, the ethnicities of the patients in our study population were also markedly different from prior studies. According to the 2006 US Census Bureau15, the city of Miami Beach, FL, USA, is composed of 53.4% of individuals of Hispanic or Latino origin, 41.2% of Caucasian (excluding Caucasians of Hispanic origin), 4% Black, and 1.4% of Asian individuals. These demographic characteristics were concordant with our studied population.

The leading symptom in our study population was dyspnea, which was seen in 54% of the cases, and is in contrast to chest pain, which has been classically described in several reports.1,5,7,13,16,17 Of note, there was a high incidence (over 18%) of asymptomatic patients who had abnormal objective data (EKG, troponin I, or echocardiography). TWI was the most common EKG abnormality. This finding differs from other studies that identified ST segment elevation as the primary finding. Another difference in our cohort was the high prevalence of elevated troponin I (in over 90% of the patients), with a high mean peak level (7.6 mg/dL). The initial and follow-up left ventricular ejection fractions were similar to previous reports. Two of our patients (3.4%) had the “reverse Takotsubo” variety of SC, and this rate is comparable to previous reports.6

In our population, the Hispanics and non-Hispanics had nearly identical presentations that differed from previously described cohorts. We speculate that environmental factors might explain these differences, as it is known that diet and medication can have protective effects in cardiovascular pathologies.18,19 We subjectively perceive that our population has a high level of activity and sun exposure that would produce a satisfactory level of vitamin D, but we recognize that the lack of documentation in this regard is a study limitation. Further studies should be performed to clarify whether these factors are involved in our findings, as vitamin D deficiency is known to play a role in cardiomyopathy.20-22 Further studies will also clarify whether exercise has a protective effect against SC as previously described for other specific cardiac situations.23-25 Based on these hypotheses, future studies will compare the physical activities and vitamin D levels of SC patients at various Columbia Hospitals.

The cause of SC remains unknown. Microvascular dysfunction due to excessive catecholamines and myocyte stunning due to overt sympathetic stimulation are among the most commonly accepted theories; however, metabolic abnormalities involving myocardial calcium overload and impaired glucose metabolism may also play roles.26,27 SC is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion and is usually given after a coronary angiogram has excluded the possibility of an acute myocardial infarction. Echocardiography provides valuable diagnostic and follow-up information. The treatment is supportive, approximately 20% of patients require vasopressors.1,27

The prognosis for SC is favorable, with the complete recovery of left ventricular function typically occurring within 1-3 weeks, and the in-hospital mortality rate ranges from 1-8%.1,6,27 In our patient cohort, five patients (8.5%) died during hospitalization, which is a slightly higher rate than has been described previously. However, none of these five deaths were cardiac-related, which suggests that stress cardiomyopathy itself may represent a marker of a generally impaired health status and may not be the cause of death. The four-year recurrence rate of SC is reported to be 3-11%.1,4,6,7 During the time frame of our study, two (3.4%) of the patients had a recurrence of their stress cardiomyopathy. Of note, one patient had two recurrences of SC within four years and fully recovered from all three episodes.

Study Limitations

This study was a retrospective observational analysis of a single-center experience. The evaluation of the patients was limited to the in-hospital setting.

CONCLUSIONS

In our heterogeneous population, stress cardiomyopathy presented with a 3:2 female:male ratio, with dyspnea as the primary chief complaint and TWI as the primary EKG abnormality. These findings differ from previous reports. In a subgroup analysis, an initial EKG presentation ST wave elevation was more common among Hispanics, although it was not the most common electrocardiographic abnormality. Future studies that focus on Hispanic populations and environmental factors are needed.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, Oh-mura N, Kimura K, Owa M, et al. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Angina Pectoris–Myocardial Infarction Investigations in Japan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:11–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01316-x. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01316-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Satoh H, Tateishi H, Uchida T.Takotsubo-type cardiomyopathy due to multivessel spasm In:Kodama K, Hon M, editors. Clinical Aspect of Myocardial Injury: From Ischemia to Heart Failure (in Japanese) Tokyo: Kagakuhyouronsya Co; 199056–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawai S, Suzuki H, Yamaguchi H, Tanaka K, Sawada H, Aizawa T, et al. Ampulla cardiomyopathy (‘Takotusbo' cardiomyopathy)—reversible left ventricular dysfunction: with ST segment elevation. Jpn Circ J. 2000;64:156–9. doi: 10.1253/jcj.64.156. 10.1253/jcj.64.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Nishioka K, et al. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2002;143:448–55. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120403. 10.1067/mhj.2002.120403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akashi YJ, Nakazawa K, Sakakibara M, Miyake F, Koike H, Sasaka K. The clinical features of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. QJM. 2003;96:563–73. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg096. 10.1093/qjmed/hcg096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eshtehardi P, Koestner SC, Adorjan P, Windecker S, Meier B, Hess OM, et al. Transient apical ballooning syndrome – clinical characteristics, ballooning pattern, and long-term follow-up in a Swiss population. Int J Cardiol. 2009;135:370–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.088. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR, Maron MS, Hauser RG, Lesser JN, et al. Natural history and expansive clinical profile of stress (Tako-Tsubo) cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:333–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.057. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parodi G, Del Pace S, Carrabba N, Salvadori C, Memisha G, Simonetti I, et al. Incidence, clinical findings, and outcome of women with left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:182–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.080. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Previtali M, Repetto A, Panigada S, Camporotondo R, Tavazzi L. Left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: prevalence, clinical characteristics and pathogenetic mechanisms in a European population. Int J Cardiol. 2009;134:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.01.037. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidi V, Rajesh V, Singh PP, Mukherjee JT, Lago RM, Venesy DM, et al. Clinical characteristics of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:578–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.028. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Athanasiadis A, Vogelsberg H, Hauer B, Meinhardt G, Hill S, Sechtem U. Transient left ventricular dysfunction with apical ballooning (tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy) in Germany. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006;95:321–8. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-0380-0. 10.1007/s00392-006-0380-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auer J, Porodko M, Berent R, Punzengruber C, Weber T, Lamm G, et al. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning mimicking acute coronary syndrome in four patients from central Europe. Croat Med J. 2005;46:942–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pezzo SP, Hartlage G, Edwards CM. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy presenting with dyspnea. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:200–2. doi: 10.1002/jhm.402. 10.1002/jhm.402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel HM, Kantharia BK, Morris DL, Yazdanfar S. Takotsubo syndrome in African American women with atypical presentation: a single-center experience. 2007;30:14–8. doi: 10.1002/clc.21. Clin Cardiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/12/1245025.html

- 16.Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1523–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient ballooning syndrome: A systematic review. 2008;124:283–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.002. Int J Cardiol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrade AC, Cesena FH, Consolim-Colombo FM, Coimbra SR, Benjó AM, Krieger EM, et al. Short-term red wine consumption promotes differential effects on plasma levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, sympathetic activity, and endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive, and healthy subjects. Clinics. 2009;64:435–42. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000500011. 10.1590/S1807-59322009000500011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carnieto A, Jr, Dourado PM, Luz PL, Chagas AC. Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition protects against myocardial damage in experimental acute ischemia. Clinics. 2009;64:245–52. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000300016. 10.1590/S1807-59322009000300016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zittermann A, Schleithoff SS, Koerfer R. Vitamin D insufficiency in congestive heart failure: why and what to do about it. Heart Fail Rev. 2006;11:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s10741-006-9190-8. 10.1007/s10741-006-9190-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, Jacques PF, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117:503–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitka M. Vitamin D deficits may affect heart health. 2008;299:753–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.7.753. JAMA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negrao CE, Middlekauff HR. Adaptations in autonomic function during exercise training in heart failure. 2008;13:51–60. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9057-7. Heart Fail Rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farah C, Meyer G, André L, Boissière J, Gayrard S, Cazorla O, et al. Moderate exercise prevents impaired Ca2+ handling in heart of CO-exposed rat: implication for sensitivity to ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H2076–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00835.2010. 10.1152/ajpheart.00835.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen YJ, Pan SS, Zhuang T, Wang FJ. Exercise preconditioning initiates late cardioprotection against isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in rats independent of protein kinase C. . J Physiol Sci. 2011;61:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s12576-010-0116-9. 10.1007/s12576-010-0116-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Zenovich AG, Maron MS, Lindberg J, Longe TF, et al. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:472–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153801.51470.EB. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153801.51470.EB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurowski V, Kaiser A, von Hof K, Killermann DP, Mayer B, Hartmann F, et al. Apical and midventricular transient left ventricular dysfunction syndrome (tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy): frequency, mechanisms, and prognosis. Chest. 2007;132:809–16. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0608. 10.1378/chest.07-0608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]