Abstract

It is well-established that psychological stress promotes immune dysregulation in nonpregnant humans and animals. Stress promotes inflammation, impairs antibody responses to vaccination, slows wound healing, and suppresses cell-mediated immune function. Importantly, the immune system changes substantially to support healthy pregnancy, with attenuation of inflammatory responses and impairment of cell-mediated immunity. This adaptation is postulated to protect the fetus from rejection by the maternal immune system. Thus, stress-induced immune dysregulation during pregnancy has unique implications for both maternal and fetal health, particularly preterm birth. However, very limited research has examined stress-immune relationships in pregnancy. The application of psychoneuroimmunology research models to the perinatal period holds great promise for elucidating biological pathways by which stress may affect adverse pregnancy outcomes, maternal health, and fetal development.

Keywords: psychoneuroimmunology, pregnancy, perinatal, stress, immune function, inflammation, fetal development, adverse birth outcomes, preterm birth, maternal health

1. Adverse Birth Outcomes in the United States

Preterm delivery affects 12–13% of birth in the U.S. This rate is substantially higher than the rate of 5–9% in other developed countries (Buitendijk et al., 2003; Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes, 2007; Laws et al., 2007; Martin et al., 2007; Statistics Canada, 2008). Racial disparities contribute to, but do not fully account for, this discrepancy. In the U.S., the preterm birth rate is approximately 18% among African American women and 10.8–12.2% among White, Asian, and Hispanic women.

Preterm delivery is a leading cause of infant mortality (Callaghan et al., 2006). Surviving preterm infants are at high risk for serious health complications including respiratory, gastrointestinal, nervous system, and immune problems. Longer-term risks include cerebral palsy, mental retardation, learning difficulties, hearing and vision problems, and poor growth. Infants who are both preterm and of low birth weight evidence the greatest complications (Mattison et al., 2001). The estimated societal economic burden of preterm birth is at least $26.2 billion per year, or $51,600 per preterm infant (Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes, 2007). Advances in treatment of very preterm infants have increased survival among infants with neurodevelopmental problems (Wilson-Costello et al., 2005); thus, the long-term implications of preterm birth become more significant as survival rates improve.

Despite technological advances, identification of risk factors, and promotion of public health interventions, the preterm birth rate in the U.S. is a substantial problem. In 2008, the first slight decline in preterm birth rates was reported after three decades of increases (National Center for Health Statistics). From the early 1980s to 2006, the preterm birth rate rose by over 36% (Goldenberg et al., 2008). Although increased use of reproductive technologies is a contributing factor, this trend largely reflects lack of progress in the prevention of unexplained spontaneous preterm delivery.

1.1. Stress and Racial Disparities in Adverse Birth Outcomes

The substantial racial disparities in preterm birth among African Americans versus women of other races and ethnicities is not explained by demographic or traditional behavioral risk factors including, but not limited to, socioeconomic status, early access to prenatal care, alcohol use, smoking, nutrition, or sexual practices (for review see Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes, 2007). Theories have increasingly focused on the health implications of chronic stress associated with discriminated minority status (Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes, 2007; Giscombe and Lobel, 2005; Goldenberg et al., 2008; Green et al., 2005; Mulherin Engel et al., 2005; Simhan et al., 2003). Supporting the argument that minority status contributes to risk of preterm birth, a similar disparity is seen among Black versus White women in the United Kingdom (Aveyard et al., 2002). Moreover, rates of preterm delivery among Black women born outside the U.S. are lower than among African American women (Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes, 2007; David and Collins, 1997; Martin et al., 2007). While birth weight increases with each generation lived in the U.S. for women of European descent, there is an intergenerational decline in birth weight for women of African descent (Collins et al., 2002). These patterns of risk suggest an important role for psychosocial stress in adverse outcomes.

Notably, rates of preterm birth among Hispanic/Latina women in the U.S. (12.2%) are similar to non-Hispanic White women (11.6%), despite the fact that the socioeconomic status of Hispanics more closely resembles African Americans. The relative health of low SES Hispanic women as compared to low SES women of other races/ethnicities has been termed the “Hispanic Paradox”. However, the protective effects of Hispanic ethnicity diminish with greater acculturation to U.S. culture (Coonrod et al., 2004). Indeed, among Hispanic women, rates of preterm birth are 1.5–2 times higher among women of high versus low acculturation (Coonrod et al., 2004; Lara et al., 2005; Ruiz et al., 2008). Thus, it is projected that there will be increases in preterm births among Hispanics as the overall Hispanic population in the U.S. moves toward greater acculturation.

The public health importance of perinatal health among Hispanic women is substantial; 24% of births in the U.S. are Hispanic (U.S Census Bureau, 2009). Hispanic women have the highest birth rate, with 101 births per 1000 women of childbearing age versus 58.7 among non-Hispanic Whites and 69.3 among African Americans. Hispanics currently comprise 15% of the U.S. population. By 2050, this is projected to nearly triple, from 46.7 million to 132.8 million, thus comprising 30% of the nation’s population. Also by 2050, the number of Hispanic women at childbearing age will increase by 92%, compared to an increase of 10% among African Americans (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009).

Acculturation to U.S. culture among Hispanics may affect birth outcomes via both behavioral and physiological stress pathways. Greater acculturation is associated with more smoking, alcohol use, and street drug use as well as poorer diet during pregnancy (Chasan-Taber et al., 2008; Coonrod et al., 2004; Detjen et al., 2007). Greater acculturation has also been linked to greater internalization of ethnic stereotypes, poorer social support networks, greater exposure to stressful life events, and greater depressive symptoms (Alamilla et al., 2010; Davila et al., 2009; Sherraden and Barrera, 1996).

These patterns of risk among African Americans and Hispanic Americans provide strong support for the premise that psychosocial stress affects birth outcomes. Thus, the study of biological effects of stress among racial/ethnic minority women provides the opportunity to 1) address these critical health disparities and also 2) elucidate mechanistic pathways that may inform our understanding of links between stress and birth outcomes more generally. As reviewed below, while disparities related to racial/ethnic minority status are substantial, psychosocial stressors of other forms are also important predictors of adverse outcomes.

1.2. General Psychosocial Stress and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

Stress measured in a variety of ways has been associated with increased risk of preterm birth after controlling for traditional risk factors in over three dozen studies (for review see Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes, 2007; Savitz and Pastore, 1999). This literature has become more consistent over time, reflecting more rigorous research methodology and larger sample sizes.

Across studies, women reporting greater stress or distress exhibit 1.5 to 3 times greater risk of preterm delivery as compared to their less distressed counterparts. Supporting the conceptualization of minority status as a chronic stressor, perceived racial discrimination has repeatedly been linked to increased risk of preterm delivery and low birth weight (Collins et al., 2004; Dole et al., 2003; Dole et al., 2004; Giscombe and Lobel, 2005; Mustillo et al., 2004; Rosenberg et al., 2002). In addition, other subjective and objective indicators of stress are associated with increased risk of preterm delivery among African Americans as well as women of other races. These include perceived stress (Copper et al., 1996; Pritchard, 1994; Tegethoff et al., 2010), general distress (Hedegaard et al., 1993; Lobel et al., 1992), occurrence of stressful life events (Dole et al., 2003; Nordentoft et al., 1996; Wadhwa et al., 1993), pregnancy-specific anxiety (Dole et al., 2003; Kramer et al., 2009; Lobel et al., 2008; Mancuso et al., 2004; Rini et al., 1997; Wadhwa et al., 1993), and depressive symptoms (Grote et al., 2010; Li et al., 2009; Orr et al., 2002; Phillips et al., 2010; Steer et al., 1992).

Given differing measures of stress across studies, the exact effects and magnitude of relationships between particular measures and birth outcomes is not yet clear. However, these relationships remain after accounting for traditional behavioral risk factors, suggesting a role for more direct physiological links between stress and preterm birth. This argument is supported by animal studies; non-human primates exposed to stressors during pregnancy evidence increased risk of spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, and less developed placenta (Decatanzaro and Macniven, 1992; Myers, 1975, 1977; Valerio et al., 1969).

While 65–70% of preterm births are designated “spontaneous”, 30–35% are due to medically-indicated causes (Goldenberg et al., 2008). Stress may contribute to the latter via promotion of preeclampsia (Arck, 2001; Hetzel et al., 1961; Kanayama et al., 1997; Khatun et al., 1999; Kurki et al., 2000; Landsbergis and Hatch, 1996; Rofe and Goldberg, 1983), a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy which is a leading cause of medically indicated preterm delivery. In animal models, pregnant rats exposed to cold stimulation of the paws for two weeks develop symptoms consistent with preeclampsia (Kanayama et al., 1997; Khatun et al., 1999), supporting a role for excessive stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system in the development of the disorder (Arck, 2001). In human studies, greater stress, depressive symptoms, or anxiety early in pregnancy has been associated with 2–3 times greater risk of developing preeclampsia or gestational hypertension later in pregnancy (Kurki et al., 2000; Landsbergis and Hatch, 1996).

Evidence is mixed regarding racial disparities in the prevalence of preeclampsia; some studies have found greater prevalence among African American women (Coonrod et al., 1995; Eskenazi et al., 1991) and other studies have found no association with race (Friedman et al., 1999; Sibai et al., 1995). However, risk of hypertension is conclusively higher among African Americans in general (Ong et al., 2007), and the chronic stress of minority status is implicated in this link (Brondolo et al., 2008; Brondolo et al., 2003; Cozier et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2008). Moreover, beyond the issue of prevalence, race may affect the clinical presentation hypertensive disorders; for example, evidence indicates that African American women with severe preeclampsia exhibit more severe hypertension and require greater antihypertensive medications as compared to European American women (Goodwin and Mercer, 2005).

2. Psychoneuroimmunology Models in Pregnancy

Despite substantial literature linking psychological stress to adverse pregnancy outcomes, few studies have examined potential biological mechanisms explaining these associations and available studies have focused almost exclusively on potential neuroendocrine mediators (e.g., Hobel et al., 1999; Kramer et al., 2009; Mancuso et al., 2004; Wadhwa et al., 2004). Attention to inflammatory processes is warranted. In nonpregnant humans and animals, it is well-established that stress and distress (e.g., depressive symptoms) predict dysregulation of inflammatory processes including elevated circulating inflammatory cytokines, greater inflammatory responses to psychological stressors, and exaggerated inflammatory responses to in vitro and in vivo biological challenges (Avitsur et al., 2005; Dunn et al., 2005; Glaser et al., 2003; Irwin, 2002; Johnson et al., 2002; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2003; Lutgendorf et al., 1999; Maes, 1999; Maes et al., 1997; Miller, 1998; Musselman et al., 2001; Pace et al., 2006; Quan et al., 2001; Schiepers et al., 2005; Stark et al., 2002; Vedhara et al., 1999; Zorrilla et al., 2001). The extent to which such effects generalize to pregnancy is largely unknown.

Successful pregnancy has been associated with attenuated proinflammatory cytokine production in response to in vitro and in vivo immune challenges in human and animal studies (Aguilar-Valles et al., 2007; Elenkov et al., 2001; Fofie et al., 2004; Makhseed et al., 1999; Marzi et al., 1996). This adaptation may prevent fetal rejection by the maternal immune system and protect the fetus from excessive maternal inflammatory responses to infectious agents (Blackburn and Loper, 1992; Stables, 1999). Corresponding to these changes, temporary improvement or remission is often seen in autoimmune disorders including inflammatory arthritis (Straub et al., 2005) and multiple sclerosis (Confavreux et al., 1998; Langer-Gould et al., 2002).

Consistent with the argument that inflammation is incompatible with healthy pregnancy, elevations in proinflammatory cytokines in maternal serum and amniotic fluid including IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, resulting from infection as well as idiopathic cases, are causally implicated in risk of preterm delivery (Dizon-Townson, 2001; Murtha et al., 2007; Romero et al., 1990; Romero et al., 1993a; Romero et al., 1993b). Proinflammatory cytokines can promote preterm labor by triggering preterm contractions, encouraging cervical ripening, and causing rupture of the membranes (Hagberg et al., 2005; Romero et al., 2006).

Inflammation may also contribute to medically-indicated preterm delivery by promoting hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia are characterized by high levels of circulating inflammatory markers, including IL-6 and TNF-α (Conrad and Benyo, 1997; Conrad et al., 1998; Freeman et al., 2004; Granger, 2004; Granger et al., 2001). Supporting a causal role for inflammation in the development of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, many features of preeclampsia, including impaired lipid metabolism and endothelial dysfunction, can be induced by proinflammatory cytokines (Page, 2002) and the clinical severity of preeclampsia has been associated with the degree of dysregulation seen in cytokine function (Madazli et al., 2003).

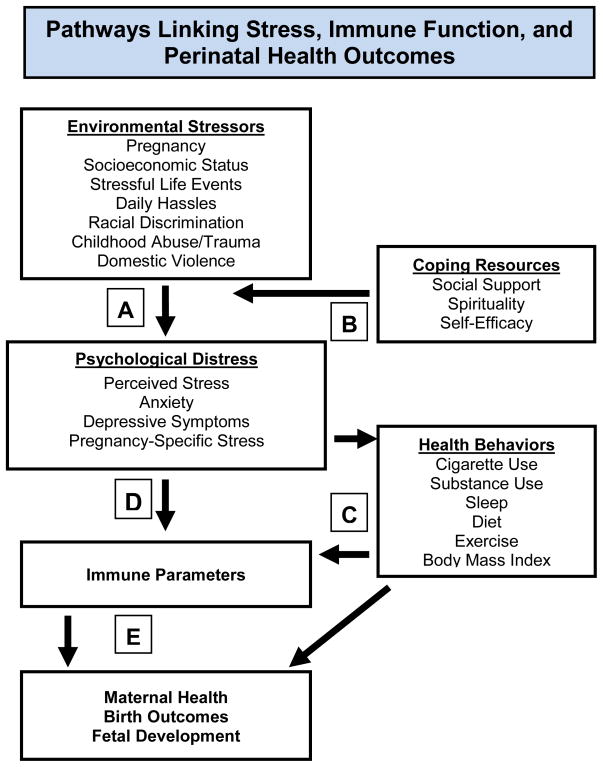

Given the unique implications of immune dysregulation during pregnancy, the lack of data regarding effects of stress on inflammatory processes in pregnant women is notable. Due to substantial changes in immune and neuroendocrine function during pregnancy, effects of stress on these parameters may differ during pregnancy as compared to nonpregnancy. Translation of PNI models to pregnancy is needed to elucidate effects of stress on inflammatory outcomes in pregnancy, including, but not limited to: 1) basal adaptation of serum inflammatory markers as pregnancy progresses, 2) inflammatory responses to biological challenges and 3) inflammatory responses to psychosocial stressors. Related literature and empirical rationale for specifics approaches are detailed below. Figure 1 depicts proposed pathways by which stress may affect maternal immune function and perinatal health outcomes.

Figure 1. Pathways Linking Stress, Immune Function, and Perinatal Health Outcomes.

Greater exposure to objectively stressful events results in greater experience of subjective distress (A). This effect is moderated by coping resources, including social support (B). Psychological distress may affect immune function via health behaviors (C) and direct physiological pathways (D) via effects on neuroendocrine and the sympathetic nervous system. In turn, immune parameters may affect maternal health (e.g., preeclampia, susceptibility to infectious illness, wound healing), birth outcomes, and fetal development (E).

2.1. Longitudinal Changes in Serum Cytokine Levels

Available data suggest that healthy pregnancy elicits mild elevations in both pro- and antiinflammatory serum cytokine levels and that exaggerated increases in circulating inflammatory markers are predictive of greater risk of spontaneous preterm delivery (Austgulen et al., 1994; Curry et al., 2007; Curry et al., 2008; Makhseed et al., 2000; Opsjon et al., 1993; Vassiliadis et al., 1998). The extent to which psychosocial stress may promote elevations in serum cytokine levels during pregnancy is largely unknown. Coussons-Read and colleagues reported that among 24 pregnant women, greater perceived stress was associated with higher circulating levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and lower levels of the antiinflammatory cytokine IL-10 in samples taken during each trimester and averaged (Coussons-Read et al., 2005). Ruiz and colleagues reported both increasing years of residency in the U.S. and depressive symptoms were associated with elevated levels of the proinflammatory marker IL-1RA among Hispanic women in mid-pregnancy (Ruiz et al., 2007).

We examined psychosocial factors and serum proinflammatory cytokines among 60 pregnant women recruited from the OSU Prenatal Clinic, which serves a diverse and largely disadvantaged population. The majority of participants were African American (57%), had completed high school or less education (82%), and reported a total annual family income of less than $15,000 per year (63%). Women were assessed at one timepoint, primarily in the late first or early second trimester (15 ± 7.8 weeks gestation). Those with greater depressive symptoms, as measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D), had higher levels of circulating IL-6 (β=.23, p=.05) and marginally higher TNF-α (β=.24, p=.06) (Christian et al., 2009b). The magnitude of this effect was similar to that reported in nonpregnant adults (e.g., Miller et al., 2002). An effect for racial differences in IL-6 approached statistical significance (t(49) = −1.6, p =.12), with African American women exhibiting non-significantly higher levels (Christian et al., 2009b). African American women did not differ significantly from European American women in depressive symptoms, education, income, or number of previous pregnancies.

These initial findings indicate that effects of psychological stress on circulating inflammatory markers are detectable in pregnancy. Further research should aim to 1) better describe typical changes in serum cytokines across the course of pregnancy; 2) examine effects of race and psychosocial stress on this adaptation in a longitudinal manner and 3) examine links between differential immune adaptation with risk of preterm birth and other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

2.2. In Vitro Stimulated Cytokine Production

In women, successful pregnancy has been associated with attenuated proinflammatory cytokine production in response to in vitro immune challenges, with the most marked changes in the 3rd trimester (Aguilar-Valles et al., 2007; Denney et al., 2011; Elenkov et al., 2001; Fofie et al., 2004; Marzi et al., 1996). This adaptation may be critical in preventing rejection of the fetus by the maternal immune system and protecting the fetus from excessive maternal inflammatory responses to infectious agents (Blackburn and Loper, 1992; Stables, 1999). Failure to demonstrate attenuation of inflammatory responses has been reported among women who subsequently experience miscarriage or deliver small for gestational age babies (Marzi et al., 1996) as well as in nonpregnant women with a history of recurrent spontaneous miscarriage versus women with a history of successful pregnancy (Makhseed et al., 1999). Thus, factors influencing appropriate adaptation of inflammatory responses may affect risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

As described earlier, exaggerated inflammatory responses to in vitro antigen challenge are seen in animals exposed to repeated stressors as well as in humans with major depressive disorder (Anisman et al., 1999; Maes, 1995, 1999). One study has demonstrated such effects in pregnancy; among 17 women assessed during the 3rd trimester, greater subjective stress predicted exaggerated production of IL-1β and IL-6 by lymphocytes stimulated in vitro (Coussons-Read et al., 2007). Thus, emerging data suggest that stress alters the inflammatory response to immune triggers in human pregnancy. As with studies of basal adaptation, studies of in vitro stimulated cytokine production that include larger samples, longitudinal research design, and address potential racial differences would be highly informative. In part due to greater variation, and thus stronger ability to clearly classify women (e.g., high versus low responders), the inflammatory response to immune triggers may prove to be a stronger predictor of adverse pregnancy outcomes than basal serum levels of markers.

2.3. Influenza Virus Vaccination as an In Vivo immune Challenge

For clear ethical reasons, human studies of the inflammatory response system in pregnant women to-date have relied almost exclusively on in vitro models (Elenkov et al., 2001; Marzi et al., 1996). Although highly useful, in vitro techniques involve isolation of specific cells, removal of cells from the complex in vivo environment, and exposure to higher levels of antigen than normally occurs in vivo (Cohen et al., 2001; Vedhara et al., 1999). By providing insight into immune function in the complex, multifaceted, naturally-occurring environment, in vivo models may provide data with clearer clinical relevance.

Seasonal influenza virus vaccination provides a novel model for examining inflammatory responses to an in vivo immune challenge among pregnant women. Because pregnant women are considered at greater risk than the general population for complications, hospitalization, and death due to influenza (Dawood et al., 2009; Jamieson et al., 2009; Kuehn, 2009), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommend that all women who are pregnant or will be pregnant during flu season be vaccinated (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2010). However, only 12–13% of pregnant women receive vaccination each year (Fiore et al., 2008). Thus, utilizing vaccination as a research model also promotes current clinical recommendations.

Vaccines have been used as a model to examine in vivo inflammatory responses in non-pregnant adults (Carty et al., 2006; Doherty et al., 1993; Glaser et al., 2003; Hingorani et al., 2000; Posthouwer et al., 2004; van der Beek et al., 2002). It has been suggested that individual variation in responses to vaccines, as a mild inflammatory trigger, may predict cardiovascular risk. Greater inflammatory responses to vaccines have been reported among older adults with greater depressive symptoms (Glaser et al., 2003) as well as men with carotid artery disease (Carty et al., 2006), suggesting that responses to vaccination differ among those experiencing conditions with an inflammatory component. As adverse perinatal health outcomes including preeclampsia and preterm birth have an inflammatory component, variations in in vivo inflammatory responses may provide clinically meaningful information regarding risk for adverse outcomes and biological mechanisms underlying risk.

We have demonstrated that psychosocial factors are associated with differential inflammatory responses to trivalent influenza virus vaccine in pregnant women. Twenty-two pregnant women were assessed prior to and approximately one week after vaccination (Christian et al., 2010). Compared to those in the lowest tertile of CES-D scores (n=8), those in the highest tertile (n=6) had significantly higher levels macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) at one week post-vaccination. Groups did not differ in demographics (e.g., age, BMI, race, income) or health behaviors (e.g., sleep, smoking, regular exercise).

The absence of inflammatory response at one week post-vaccination among women with lower depressive symptoms is consistent with previous evidence that seasonal influenza virus vaccination does not generally cause an extended inflammatory response (Glaser et al., 2003; Posthouwer et al., 2004; Tsai et al., 2005). Thus, the extended inflammatory responses seen among the more depressed women are indicative of dysregulation of normal inflammatory processes. This study provides evidence that psychological stress predicts sensitization of inflammatory responses to an in vivo immune trigger during human pregnancy.

This study provides the basis for additional research questions of importance. First, with only a single follow-up timepoint at approximately one week post-vaccination, this study did not capture the initial magnitude as well as duration of an extended inflammatory response. Also of interest is the relative magnitude and duration of response at different stages of gestation and during pregnancy versus nonpregnancy. Finally, clearly an ultimate goal in applying this research model is recruitment of a substantial cohort to allow for examination of inflammatory responses in relation to risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

These research directions are suggested in relation to conceptualizing vaccination as a model for understanding a general propensity toward inflammatory responding. However, there are also important gaps in our knowledge of the effects of vaccination itself on maternal and fetal health. As described, vaccination is considered beneficial and is standardly recommended to all pregnant women who have no known medical contraindication (e.g., egg allergy). While influenza infection in pregnancy has been associated with significant complications, studies of vaccination have shown no increased risk of fetal malformations or mortality to age four among offspring and no increased risk of either C-section or preterm labor (Black et al., 2004; Heinonen et al., 1973; Heinonen et al., 1977). In fact, emerging data indicate that, among infants born during influenza season, maternal vaccination reduces risk of preterm delivery and small for gestational age birth (Omer et al., 2011). Maternal vaccination has also been associated with 63% reduction in clinical influenza in infants from birth to six months of age, during which vaccination is not permitted (Englund et al., 1993; Puck et al., 1980; Reuman et al., 1987; Zaman et al., 2008).

Further, maternal influenza infection has been linked to increased risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring,(O’Callaghan et al., 1991) a risk that vaccination could mitigate. However, given that this link may be mediated by the maternal inflammatory response to infection (see Maternal Stress and Fetal Development), it has been postulated that the inflammatory response to vaccination may itself be detrimental to fetal brain development (Brown and Patterson, 2011). Given limited data regarding safety, universal vaccination of pregnant women has been a topic of debate (Ayoub and Yazbak, 2008; Brown and Patterson, 2011). The inflammatory response elicited by vaccination is considerably milder and more transient than that elicited by infection (Hayden et al., 1998), arguing for protective benefits of vaccination. However, greater research is needed confirm that the mild inflammatory response elicited by influenza virus vaccine is benign in pregnacy, including birth cohort studies examining maternal cytokine responses to vaccination in conjunction with long-term offspring health outcomes (Brown and Patterson, 2011).

2.4. Inflammatory Responses to Psychological Stressors

Differential physiological reactivity to acute stress is an important predictor of health outcomes in nonpregnant populations (Linden et al., 1997; McEwen, 2004, 2008; Segerstrom and Miller, 2004; Stewart and France, 2001; Treiber et al., 2003). More than one dozen studies have examined cardiovascular and neuroendocrine reactivity to acute stress in pregnancy. Overall these data suggest that stress responses are attenuated during healthy pregnancy (Barron et al., 1986; de Weerth and Buitelaar, 2005; Entringer et al., 2010; Kammerer et al., 2002; Matthews and Rodin, 1992; Nisell et al., 1986; Nisell et al., 1985a, b, 1987). Similar attenuation of responsivity has been reported in animal models (Neumann et al., 1998; Neumann et al., 2000; Rohde et al., 1983). These adaptations may be critical from protecting the mother and fetus from excessive exposure to physiological activation.

There are several important limitations to the existing literature on stress reactivity in pregnancy. With some exceptions (e.g., Entringer et al., 2010), most have relied on relatively small sample sizes (n=8–20). Few have utilized nonpregnant control groups, measured recovery post-stressor, or included both neuroendocrine and cardiovascular measures. Moreover, no studies have utilized impedance cardiography which provides valuable, clinically relevant information about mechanisms controlling cardiovascular function. Thus, our understanding of typical adaptation of the stress response across the course of pregnancy as compared to nonpregnancy is incomplete.

In addition, no studies of stress reactivity in pregnancy have examined inflammatory responses. As described earlier, acute stress in the form of exposure to a novel environment, foot shock, or tail shock induces increases in circulating proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6 in animals (LeMay et al., 1990; Zhou et al., 1993). Further, this physiological response to stress can be conditioned; after repeated shocking, exposure to stimuli that were present when shocks were administered elicits increases in IL-6 (Johnson et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 1993). In humans, greater and more extended inflammatory responses to acute stress have been documented among young adults with major depressive disorder versus without (Pace et al., 2006) as well as those from low versus high socioeconomic backgrounds (Brydon et al., 2004). With particular relevance to the perinatal period, among 66 women, those with a history of major depression exhibited greater circulating IL-6 in the days following childbirth, which may be conceptualized as both a physical and psychological stressor (Maes et al., 2001). A tendency toward exaggerated inflammatory responding to daily life stressors may represent an individual difference in vulnerability to disease in the general population and adverse perinatal health outcomes in pregnant women.

Studies of stress reactivity have particular relevance in the context of understanding racial and ethnic disparities in perinatal health outcomes. Exposure to repeated and/or chronic stressors may alter the stress response. Indeed, numerous studies of nonpregnant adults demonstrate that race and exposure to racism predicts greater cardiovascular reactivity to acute stressors (Anderson, 1989; Anderson et al., 1993; Fredrikson, 1986; Gillin et al., 1996; Lepore et al., 2006; Light et al., 1993; Saab et al., 1992). In addition, stressors of a racially provocative nature elicit stronger cardiovascular responses among African Americans than do stressors that are racially neutral (Brondolo et al., 2003).

Few studies have examined racial differences in cardiovascular reactivity during pregnancy or potential links of reactivity with gestation age at delivery. Among 313 pregnant women assessed at 28 weeks gestation, African American women exhibited greater systolic and diastolic blood pressure reactivity to an acute stressor (Hatch et al., 2006). Among African Americans only, each 1-mm Hg increase in diastolic blood pressure was associated with a reduction in gestational age of 0.17 weeks. In a similar study, among 40 healthy pregnant women, each 1mmHg increase in diastolic blood pressure above the group mean in response to an arithmetic task predicted 0.314 weeks shorter gestation and marginally significant interaction between diastolic reactivity and race was evidenced, suggesting a stronger association among African Americans (McCubbin et al., 1996). Finally, in a study of 70 healthy women in Argentina, every unit increase in diastolic blood pressure reactivity to a cold pressor text was associated with a 47 gram decrease in birth weight and a 0.07 week decrease in gestational age (Gomez Ponce de Leon et al., 2001).

Building upon these studies, continued studies are needed to more fully delineate the extent to which neuroendocrine, cardiovascular and inflammatory responses adapt during pregnancy compared to nonpregnancy, predictors of differential adaptation of the stress response (e.g., race, SES, depressive symptoms, health behaviors), and the extent to which differential physiological reactivity to acute stress predicts risk of adverse outcomes.

3. Beyond Birth Outcomes: Maternal Stress and Fetal Development

In addition to effects on maternal health (i.e., preeclampsia) and birth outcomes, both prenatal stress and inflammatory processes during pregnancy have implications for fetal development (Coe and Lubach, 2005). In relation to immune function, in monkeys and rats, offspring of mothers who were repeatedly stressed during their pregnancies showed decrements in lymphocyte proliferation when exposed to antigens in vivo or in vitro (Coe et al., 2002; Kay et al., 1998; Reyes and Coe, 1997). In non-human primates, repeated exposure to stress during pregnancy affected the transfer of antibodies across the placenta (Coe and Crispen, 2000). Maternal stress can also indirectly alter offspring immune function via effects on preterm birth and fetal weight. In part because maternal antibodies are transferred to the fetus primarily in the final weeks of pregnancy, infants born prematurely are likely to have significantly impaired immune function, putting them at greater risk for infection (Ballow et al., 1986). Furthermore, low birth weight has been associated with poorer antibody response to vaccination in adolescence (McDade et al., 2001), higher cortisol responses to acute psychosocial stress in adulthood (Wust et al., 2005), and increased risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders including diabetes later in life (Lawlor et al., 2005; Rich-Edwards et al., 1999).

Animal models provide evidence that inflammation during pregnancy affects offspring health. In mice, maternal exposure to an endotoxin resulted in increased placental vascular resistance and cardiac dysfunction in developing fetuses (Rounioja et al., 2005). In rats, peripheral injection of IL-6 to pregnant females led to both hypertension and prolonged hormonal responses to acute stress in adult offspring (Samuelsson et al., 2004). Similarly, adult offspring of rats exposed to an endotoxic challenge had increased basal corticosterone levels as well as increased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and corticosterone responses to acute stress (Reul et al., 1994). These data suggest that inflammation of sufficient magnitude during pregnancy can have lasting effects on offspring physiology.

In humans, the offspring characteristics that are perhaps most widely studied in the context of maternal inflammation are the neurodevelopmental disorders of cerebral palsy and schizophrenia. Offspring of women who experience infections during pregnancy have an increased risk for both disorders (Dammann and Leviton, 1997; Yoon et al., 2003). For example, intrauterine infections and resulting inflammation are believed to account for 12% of cases of spastic cerebral palsy (Schendel et al., 2002). Indicative of the role of inflammation in this association, in a sample of 172 neonates, higher levels of IL-6 in cord blood predicted occurrence of brain lesions, a key risk factor for the development of cerebral palsy (Yoon et al., 1996). Similarly, elevated circulating levels of maternal TNF-α as well as greater reporting of maternal infection during the third trimester of pregnancy were found in 27 adult offspring with schizophrenia as compared to 50 matched controls (Buka et al., 2001).

Being non-experimental in design, studies with humans cannot determine the degree to which effects of infection on the brain of the developing fetus are attributable to infection itself versus maternal inflammatory immune responses to the infection (Gayle et al., 2004). However, animal studies indicate that inflammation is a major factor. For example, stimulation of the maternal immune system by injection of LPS affected myelination in the developing rodent brain (Cai et al., 2000) as well as the number and size of specific cells in the hippocampus of offspring (Golan et al., 2005). These effects, in turn, were associated with impairments in learning and memory (Golan et al., 2005). Also in rodents, stimulation of the immune system with a synthetic cytokine releaser during pregnancy resulted in abnormal behavioral and pharmacological responses in adult offspring, alterations that parallel characteristics of schizophrenia in humans (Zuckerman et al., 2003; Zuckerman et al., 2005). These data indicate that inflammation during pregnancy can affect fetal brain development. Thus, both maternal stress and inflammatory processes may have serious implications for offspring health into adulthood (Coe and Lubach, 2005; Weinstock, 2005).

4. Beyond Inflammation: Additional Immune Parameters

Although the current review focuses on the relevance of inflammatory processes for adverse pregnancy outcomes, other psychoneuroimmunology research models also have important applications in pregnancy. Psychological stress impairs antibody responses to a variety of vaccinations in nonpregnant adults (Burns and Gallagher, 2010; Christian et al., 2009a; Cohen et al., 2001; Pedersen et al., 2009). A meta-analysis of 13 studies of seasonal trivalent influenza vaccination concluded that greater stress predicted significantly poorer antibody responses (Cohen’s d=.37) with similar effects noted in older as well as younger adults (Pedersen et al., 2009). Despite substantial immune changes in pregnancy, no studies have examined effects of stress on antibody responses to vaccination among pregnant women. The clinical protection provided by influenza vaccination is closely correlated with antibody responses to the vaccination (Couch and Kasel, 1983; Hannoun et al., 2004; Potter and Oxford, 1979). Thus, stress-induced decrements in antibody responses to vaccination have clear clinical implications for subsequent risk of infectious illness.

Stress-induced dysregulation of cell-mediated immune function is another future focus. Over 90% of U.S. adults are latently infected with EBV (Jones and Straus, 1987). Typically kept in a latent state by cell-mediated immunity, the virus may reactivate under conditions of immunosuppression, including stress (Glaser et al., 2005; Glaser et al., 1994; Glaser et al., 1991). In fact, a meta-analysis of 20 different immune outcomes found that EBV reactivation was the strongest and most reliable correlate of stress (Van Rood et al., 1993), indicating that this is a highly sensitive measure of stress-induced immune dysregulation. Notably, due to suppression of cell-mediated immunity, EBV is more likely to be reactivated during pregnancy than nonpregnancy (Purtilo and Sakamoto, 1982). Stress may exaggerate this typical pregnancy-related immunosuppression; greater EBV reactivation in pregnancy has been reported in association with maternal depression, perceived stress and perceived racial discrimination (Borders et al., 2010; Haeri et al., 2011). Evidence is inconclusive regarding whether EBV reactivation is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. At least one study found no association between EBV reactivation and length of gestation/congenital abnormalities (Avgil et al., 2008). Two studies have linked reactivation to adverse pregnancy outcomes including stillbirth (Icart et al., 1981), birth defects (Icart et al., 1981), shorter gestation (Eskild et al., 2005), and lower birth weight (Eskild et al., 2005). Also, some data link maternal EBV reactivation to risk of leukemia and testicular cancer in offspring (Holl et al., 2008; Lehtinen et al., 2003; Tedeschi et al., 2007). However, these studies do not indicate whether EBV reactivation plays a causal role or serves as a general marker of a pathological process. Thus, continued studies examining effects of stress on EBV latency and pregnancy outcomes are warranted.

Wound healing presents another clinically relevant outcome of interest. Childbirth results in substantial tissue damage, whether delivery occurs vaginally or via cesarean section. In humans, impaired wound healing is seen in conditions of chronic stress (e.g., caregiving) (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1995), as well as exposure to milder stressors including academic examinations (Marucha et al., 1998) and martial conflict (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005). Subjective stress, anxiety, and worry have also been associated with slower healing of laboratory induced and naturally occurring wounds (Broadbent et al., 2003; Cole-King and Harding, 2001; Ebrecht et al., 2004). Similar stress-induced delays in skin barrier recovery are seen when tape-stripping is used to remove a layer of skin cells, causing mild skin barrier disruption (for review see Christian et al., 2006). No studies have examined effects of stress on wound healing in pregnancy; however, evidence from animal studies suggests that lactation is beneficial for healing, and that this effect may be mediated by suppression of stress hormones (Detillion et al., 2003).

5. Additional Considerations

In relation to inflammatory mediators, the current review has focused on peripheral (i.e., circulating) immune markers, rather than local immune parameters (i.e., at the maternal-fetal interface). This focus is supported by data demonstrating adaptation of the maternal immune system at the level of circulating markers and lack of such adaptation in the context of adverse pregnancy outcomes (Aguilar-Valles et al., 2007; Blackburn and Loper, 1992; Elenkov et al., 2001; Fofie et al., 2004; Makhseed et al., 1999; Marzi et al., 1996; Stables, 1999). Further, circulating factors can be measured in a minimally invasive manner across the course of human pregnancy and could therefore provide great clinical utility for detecting women at risk for adverse outcomes during pregnancy. However, there are numerous avenues for research beyond this level of analysis.

First, the extent to which local factors correspond to circulating measures and the relative predictive value of each for adverse perinatal health outcomes is not known. Thus, inclusion of placental measures, as well as cervico-vaginal fluid samples and measures of cervical length by transvaginal ultrasound to delineate links between systemic versus local inflammatory processes is an important direction. Relatedly, there is a large literature in reproductive immunology focusing on uterine immune changes required for implantation and maternal-fetal immune interactions throughout pregnancy (e.g., Cross et al., 1994; Dekel et al., 2010; Erlebacher, 2010; Mor et al., 2011; Trowsdale and Betz, 2006). In addition, placental infection is a known risk factor for poor birth outcomes and fetal brain damage (e.g., Cardenas et al., 2010; Grether and Nelson, 1997; Leviton et al., 1999). Stress may increase susceptibility to infectious agents and promote greater inflammatory responses upon infection, thereby exacerbating negative sequelae. Finally, genetic polymorphisms which promote proinflammatory cytokine production may contribute to individual differences in stress-induced dysregulation of inflammatory processes at both the local and systemic level. Some such polymorphisms may differentially affect African Americans versus European Americans (Ness et al., 2004; Simhan et al., 2003). However, extensive research indicates that the direct contribution of genetic factors to racial health disparities is secondary to social and environmental exposures (Institute of Medicine, 2003; Sankar, 2006; Sankar et al., 2004). Thus, the study of genetic factors should carefully account for gene/environment interactions.

6. Conclusions

A substantial literature now demonstrates that psychosocial stress has meaningful effects on maternal health, birth outcomes, and fetal development. Such effects have particular relevance to understanding substantial and intractable racial disparities in perinatal health outcomes. Biological mechanisms linking stress with maternal and fetal health have only begun to be delineated. Although it is widely proposed that inflammatory processes contribute to the association of psychosocial stress with preterm birth, studies to-date have focused almost exclusively on potential neuroendocrine mediators. As outlined, research is needed to delineate effects of stress on adaptation of inflammatory processes across pregnancy at the level of 1) circulating cytokines levels, 2) inflammatory responses to in vivo and in vitro immune triggers and 3) inflammatory responses in the context of psychosocial stressors. In addition, effects of stress on wound healing, cellular immune function, and antibody responses to vaccination in pregnancy are largely unstudied. The application of well-established psychoneuroimmunology research models to the context of pregnancy has great promise for elucidating mechanisms underlying risk of adverse perinatal health outcomes and providing a basis for individualized health care services.

Highlights.

Maternal immune dysregulation has important implications for maternal health, birth outcomes, and fetal development.

It is known that stress promotes immune dysregulation in nonpregnant humans and animals.

Emerging data demonstrate that stress affects maternal immune parameters during pregnancy.

PNI models may elucidate biological pathways linking stress and health in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

Manuscript preparation was supported by NICHD (R21HD061644; R21HD067670). The studies described were also supported by Award Number UL1RR025755 from the National Center for Research Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguilar-Valles A, Poole S, Mistry Y, Williams S, Luheshi GN. Attenuated fever in rats during late pregnancy is linked to suppressed interieukin-6 production after localized inflammation with turpentine. Journal of Physiology-London. 2007;583:391–403. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamilla SG, Kim BSK, Lam NA. Acculturation, enculturation, perceived racism, minority status stressors, and psychological symptomatology among latino/as. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2010;32:55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NB. Racial-differences in stress-induced cardiovascular reactivity and hypertension - current status and substantive issues. Psychol Bull. 1989;105:89–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NB, McNeilly M, Myers H. A biopsychosocial model of race differences in vascular reactivity. In: Blascovich J, Katkin ES, editors. Cardiovascular reactivity to psychological stress & disease. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C: 1993. pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Anisman H, Ravindran AV, Griffiths J, Merali Z. Endocrine and cytokine correlates of major depression and dysthymia with typical or atypical features. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:182–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arck PC. Stress and pregnancy loss: Role of immune mediators, hormones, and neurotransmitters. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2001;46:117–123. doi: 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2001.460201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austgulen R, Lien E, Liabakk NB, Jacobsen G, Arntzen KJ. Increased levels of cytokines and cytokine activity modifiers in normal-pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;57:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aveyard P, Cheng KK, Manaseki S, Gardosi J. The risk of preterm delivery in women from different ethnic groups. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109:894–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avgil M, Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Arnon J, Wajnberg R, Ornoy A. Epstein-barr virus infection in pregnancy--a prospective controlled study. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25:468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avitsur R, Kavelaars A, Heijnen C, Sheridan JF. Social stress and the regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub DM, Yazbak FE. A closer look at influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:660–661. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70236-6. author reply 661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballow M, Cates KL, Rowe JC, Goetz C, Desbonnet C. Development of the immune system in very low birth weight (less than 1500g) premature infants: Concentrations of plasma immunoglobulins and patterns of infection. Pediatr Res. 1986;20:899–904. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198609000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron WM, Mujais SK, Zinaman M, Bravo EL, Lindheimer MD. Plasma-catecholamine responses to physiological stimuli in normal human-pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:80–84. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SB, Shinefield HR, France EK, Fireman BH, Platt ST, Shay D. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine during pregnancy in preventing hospitalizations and outpatient visits for respiratory illness in pregnant women and their infants. Am J Perinatol. 2004;21:333–339. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-831888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn ST, Loper DL. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal physiology: A clinical perspective. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Borders AE, Grobman WA, Amsden LB, McDade TW, Sharp LK, Holl JL. The relationship between self-report and biomarkers of stress in low-income reproductive-age women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:577, e571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Alley PG, Booth RJ. Psychological stress impairs early wound repair following surgery. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:865–869. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088589.92699.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Libby DJ, Denton EG, Thompson S, Beatty DL, Schwartz J, Sweeney M, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Pickering TG, Gerin W. Racism and ambulatory blood pressure in a community sample. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:49–56. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815ff3bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Rieppi R, Kelly KP, Gerin W. Perceived racism and blood pressure: A review of the literature and conceptual and methodological critique. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:55–65. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2501_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Patterson PH. Maternal infection and schizophrenia: Implications for prevention. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:284–290. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydon L, Edwards S, Mohamed-Ali V, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic status and stress-induced increases in interleukin-6. Brain, Behav, Immun. 2004;18:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitendijk S, Zeitlin J, Cuttini M, Langhoff-Roos J, Bottu J. Indicators of fetal and infant health outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;111(Suppl 1):S66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Tsuang MT, Torrey EF, Klebanoff MA, Wagner RL, Yolken RH. Maternal cytokine levels during pregnancy and adult psychosis. Brain, Behav, Immun. 2001;15:411–420. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns VE, Gallagher S. Antibody response to vaccination as a marker of in vivo immune function in psychophysiological research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S, Pan ZO, Pang Y, Evans OB, Rohodes PG. Cytokine induction in fetal rat brains and brain injury in neonatal rats after maternal lipopolysacharide adminstration. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:64–72. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan WM, MacDorman MF, Rasmussen SA, Qin C, Lackritz EM. The contribution of preterm birth to infant mortality rates in the united states. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1566–1573. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas I, Means RE, Aldo P, Koga K, Lang SM, Booth C, Manzur A, Oyarzun E, Romero R, Mor G. Viral infection of the placenta leads to fetal inflammation and sensitization to bacterial products predisposing to preterm labor. J Immunol. 2010;185:1248–1257. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty CL, Heagerty P, Nakayama K, McClung EC, Lewis J, Lum D, Boespflug E, McCloud-Gehring C, Soleimani BR, Ranchalis J, Bacus TJ, Furlong CE, Jarvik GP. Inflammatory response after influenza vaccination in men with and without carotid artery disease. Atertio Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2738–2744. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000248534.30057.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. MMWR. 2009;58:RR-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Pekow P, Sternfeld B, Solomon CG, Markenson G. Predictors of excessive and inadequate gestational weight gain in hispanic women. Obesity. 2008;16:1657–1666. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Deichert N, Gouin J-P, Graham JE, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Psychological influences on neuroendocrine and immune outcomes. In: Cacioppo JT, Berntson G, editors. Handbook of neuroscience for the behavioral sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New Jersey: 2009a. pp. 1260–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Franco A, Glaser R, Iams J. Depressive symptoms are associated with elevated serum proinflammatory cytokines among pregnant women. Brain, Behav, Immun. 2009b;23:750–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Franco A, Iams JD, Sheridan J, Glaser R. Depressive symptoms predict exaggerated inflammatory response to in vivo immune challenge during human pregnancy. Brain, Behav, Immun. 2010;24:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Graham JE, Padgett DA, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress and wound healing. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2006;13:337–346. doi: 10.1159/000104862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe CL, Crispen HR. Social stress in pregnant monkeys differentially affects placental transfer of maternal antibody to male and female infants. Health Psychol. 2000;19:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe CL, Kramer MS, Kirschbaum C, Netter P, Fuchs E. Prenatal stress diminishes the cytokine response of leukocytes to endotoxin stimulation in juvenile rhesus monkeys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:675–681. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe CL, Lubach GR. Prenatal origins of individual variation in behavior and immunity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Miller GE, Rabin BS. Psychological stress and antibody response to immunization: A critical review of the human literature. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:7–18. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole-King A, Harding KG. Psychological factors and delayed healing in chronic wounds. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:216–220. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW, David RJ, Handler A, Wall S, Andes S. Very low birthweight in african american infants: The role of maternal exposure to interpersonal racial discrimination. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2132–2138. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW, Wu SY, David RJ. Differing intergenerational birth weights among the descendants of us-born and foreign-born whites and african americans in illinois. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:210–216. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm birth: Causes, consequences, and prevention. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours mM, Cortinovis-Tourniaire P, Moreau T. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. New Engl J Med. 1998;339:285–291. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KP, Benyo DF. Placental cytokines and the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;37:240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KP, Miles TM, Benyo DF. Circulating levels of immunoreactive cytokines in women with preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1998;40:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonrod DV, Bay RC, Balcazar H. Ethnicity, acculturation and obstetric outcomes. Different risk factor profiles in low- and high-acculturation hispanics and in white non-hispanics. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonrod DV, Hickok DE, Zhu KM, Easterling TR, Daling JR. Risk-factors for preeclampsia in twin pregnancies - a population-based cohort study. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:645–650. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00049-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Elder N, Swain M, Norman G, Ramsey R, Cotroneo P, Collins BA, Johnson F, Jones P, Meier AM. The preterm prediction study: Maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1286–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch RB, Kasel JA. Immunity to influenza in man. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1983;37:529–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.002525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussons-Read ME, Okun ML, Nettles CD. Psychosocial stress increases inflammatory markers and alters cytokine production across pregnancy. Brain, Behav, Immun. 2007;21:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussons-Read ME, Okun ML, Schmitt MP, Giese S. Prenatal stress alters cytokine levels in a manner that may endanger human pregnancy. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:625–631. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000170331.74960.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozier Y, Palmer JR, Horton NJ, Fredman L, Wise LA, Rosenberg L. Racial discrimination and the incidence of hypertension in us black women. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JC, Werb Z, Fisher SJ. Implantation and the placenta: Key pieces of the development puzzle. Science. 1994;266:1508–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.7985020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AE, Vogel I, Drews C, Schendel D, Skogstrand K, Flanders WD, Hougaard D, Olsen J, Thorsen P. Mid-pregnancy maternal plasma levels of interleukin 2, 6, and 12, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interferon-gamma, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and spontaneous preterm delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:1103–1110. doi: 10.1080/00016340701515423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AE, Vogel I, Skogstrand K, Drews C, Schendel DE, Flanders WD, Hougaard DM, Thorsen P. Maternal plasma cytokines in early- and mid-gestation of normal human pregnancy and their association with maternal factors. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;77:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann O, Leviton A. Maternal intrauterine infection, cytokines, and brain damage in the preterm newborn. Pediatr Res. 1997;42:1–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David RJ, Collins JW. Differing birth weight among infants of us-born blacks, african-born blacks, and us-born whites. New Engl J Med. 1997;337:1209–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila M, McFall SL, Cheng D. Acculturation and depressive symptoms among pregnant and postpartum latinas. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:318–325. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, Gubareva LV, Xu XY, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza a (h1n1) virus in humans novel swine-origin influenza a (h1n1) virus investigation team. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:2605–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weerth C, Buitelaar JK. Physiological stress reactivity in human pregnancy - a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:295–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decatanzaro D, Macniven E. Psychogenic pregnancy disruptions in mammals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel N, Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Mor G. Inflammation and implantation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denney JM, Nelson EL, Wadhwa PD, Waters TP, Mathew L, Chung EK, Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF. Longitudinal modulation of immune system cytokine profile during pregnancy. Cytokine. 2011;53:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detillion C, Hunzeker J, Craftseng R, Sheridan J, DeVries C. Wound healing is affected by parturition and lactation; Society for Neuroscience Annual meeting; New Orleans, USA. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Detjen MG, Nieto FJ, Trentham-Dietz A, Fleming M, Chasan-Taber L. Acculturation and cigarette smoking among pregnant hispanic women residing in the united states. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2040–2047. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizon-Townson DS. Preterm labour and delivery: A genetic predisposition. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:57–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty JF, Golden MHN, Raynes JG, Griffin GE, Mcadam KPWJ. Acute-phase protein response is impaired in severely malnourished children. Clin Sci. 1993;84:169–175. doi: 10.1042/cs0840169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:14–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole N, Savitz DA, Siega-Riz AM, Hertz-Picciotto I, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Psychosocial factors and preterm birth among african american and white women in central north carolina. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1358–1365. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ, Swiergiel AH, de Beaurepaire R. Cytokines as mediators of depression: What can we learn from animal studies? Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:891–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrecht M, Hextall J, Kirtley LG, Taylor A, Dyson M, Weinman J. Perceived stress and cortisol levels predict speed of wound healing in healthy male adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:798–809. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Bakalov VK, Link AA, Dimitrov MA, Fisher S, Crane M, Kanik KS, Chrousos GP. Il-12, tnf-alpha, and hormonal changes during late pregnancy and early postpartum: Implications for autoimmune disease activity during these times. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4933–4938. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund JA, Mbawuike IN, Hammill H, Holleman MC, Baxter BD, Glezen WP. Maternal immunization with influenza or tetanus toxoid vaccine for passive antibody protection in young infants. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:647–656. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.3.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Buss C, Shirtcliff EA, Cammack AL, Yim IS, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD. Attenuation of maternal psychophysiological stress responses and the maternal cortisol awakening response over the course of human pregnancy. Stress. 2010;13:258–268. doi: 10.3109/10253890903349501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlebacher A. Immune surveillance of the maternal/fetal interface: Controversies and implications. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Fenster L, Sidney S. A multivariate analysis of risk factors for preeclampsia. JAMA. 1991;266:237–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskild A, Bruu AL, Stray-Pedersen B, Jenum P. Epstein-barr virus infection during pregnancy and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112:1620–1624. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, Iskander JK, Uyeki TM, Mootrey G, Bresee JS, Cox NJ. Prevention and control of influenza: Recommendations of the advisory commitee on immunization practices, 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fofie AE, Fewell JE, Moore SL. Pregnancy influences the plasma cytokine response to intraperitoneal administration of bacterial endotoxin in rats. Exp Physiol. 2004;90:95–101. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.028613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrikson M. Racial-differences in cardiovascular reactivity to mental stress in essential-hypertension. J Hypertens. 1986;4:325–331. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman DJ, McManus F, Brown EA, Cherry L, Norrie J, Ramsay JE, Clark P, Walker ID, Sattar N, Greer IA. Short- and long-term changes in plasma inflammatory markers associated with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2004;43:708–714. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143849.67254.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SA, Schiff E, Lubarsky SL, Sibai BM. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;42:470–478. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayle DA, Beloosesky R, Desai M, Amidi F, Nunez SE, Ross MG. Maternal lps induces cytokines in the amniotic fluid and corticotropin releasing hormone in the fetal rat brain. Am J Physiol. 2004;208:1024–1029. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00664.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillin JL, Mills PJ, Nelesen RA, Dillon E, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE. Race and sex differences in cardiovascular recovery from acute stress. Int J Psychophysiol. 1996;23:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(96)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giscombe CL, Lobel M. Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among african americans: The impact of stress, racism, and related factors in pregnancy. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:662–683. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Padgett DA, Litsky ML, Baiocchi RA, Yang EV, Chen M, Yeh PE, Klimas NG, Marshall GD, Whiteside T, Herberman R, Kiecolt-Glaser J, Williams MV. Stress-associated changes in the steady-state expression of latent epstein-barr virus: Implications for chronic fatigue syndrome and cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Pearl DK, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Malarkey WB. Plasma cortisol levels and reactivation of latent epstein-barr virus in response to examination stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1994;19:765–772. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Pearson GR, Jones JF, Hillhouse J, Kennedy S, Mao HY, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-related activation of epstein-barr virus. Brain Behav Immun. 1991;5:219–232. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(91)90018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Robles T, Sheridan J, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses following influenza vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1009–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan HM, Lev V, Hallak M, Sorokin Y, Huleihel M. Specific neurodevelopmental damage in mice offspring following maternal inflammation during pregnancy. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:903–917. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez Ponce de Leon R, Gomez Ponce de Leon L, Coviello A, De Vito E. Vascular maternal reactivity and neonatal size in normal pregnancy. Hypertension in Pregnancy. 2001;20:243–256. doi: 10.1081/PRG-100107827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin AA, Mercer BM. Does maternal race or ethnicity affect the expression of severe preeclampsia? Am. J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:973–978. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger JP. Inflammatory cytokines, vascular function, and hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R989–R990. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00157.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger JP, Alexander BT, Llinas MT, Bennett WA, Khalil RA. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia: Linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension. 2001;38:718–722. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green NS, Damus K, Simpson JL, Iams J, Reece EA, Hobel CJ, Merkatz IR, Greene MF, Schwarz RH, Committee MDSA. Research agenda for preterm birth: Recommendations from the march of dimes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grether JK, Nelson KB. Maternal infection and cerebral palsy in infants of normal birth weight. JAMA. 1997;278:207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012–1024. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeri S, Johnson N, Baker AM, Stuebe AM, Raines C, Barrow DA, Boggess KA. Maternal depression and epstein-barr virus reactivation in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:862–866. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820f3a30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg H, Mallard C, Jacobsson B. Role of cytokines in preterm labour and brain injury. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112:16–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannoun C, Megas F, Piercy J. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of influenza vaccination. Virus Res. 2004;103:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch M, Berkowitz G, Janevic T, Sloan R, Lapinski R, James T, Barth WH. Race, cardiovascular reactivity, and preterm delivery among active-duty military women. Epidemiology. 2006;17:178–182. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000199528.28234.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden FG, Fritz RS, Lobo MC, Alvord WG, Strober W, Straus SE. Local and systemic cytokine responses during experimental human influenza a virus infection - relation to symptom formation and host defense. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:643–649. doi: 10.1172/JCI1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard M, Brink Henriksen T, Sabroe S, Secher NJ. Psychological distress in pregnancy and preterm delivery. Br Med J. 1993;307:234–239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6898.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen OP, Shapiro S, Monson RR, Hartz SC, Rosenberg L, Slone D. Immunization during pregnancy against poliomyelitis and influenza in relation to childhood malignancy. Int J Epidemiol. 1973;2:229–235. doi: 10.1093/ije/2.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen OP, Slone D, Shapiro S. Immunizing agents. In: Kaufman DW, editor. Birth defects and drugs in pregnancy. Littleton Publishing Sciences Group; Boston, MA: 1977. pp. 614–321. [Google Scholar]

- Hetzel BS, Bruer B, Poidevin L. A survey of the relation between certain common antenatal compications in primparae and stressful life situations during pregnancy. J Psychosom Res. 1961;5:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(61)90044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani AD, Cross J, Kharbanda RK, Mullen MJ, Bhagat K, Taylor M, Donald AE, Palacios M, Griffin GE, Deanfield JE, MacAllister RJ, Vallance P. Acute systemic inflammation impairs endothelium-dependent dilatation in humans. Circulation. 2000;102:994–999. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobel CJ, Dunkel-Schetter C, Roesch SC, Castro LC, Arora CP. Maternal plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone associated with stress at 20 weeks’ gestation in pregnancies ending in preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:S257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70712-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holl K, Surcel HM, Koskela P, Dillner J, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Kaasila M, Olafsdottir GH, Ogmundsdottir HM, Pukkala E, Stattin P, Lehtinen M. Maternal epstein-barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections and risk of testicular cancer in the offspring: A nested case-control study. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 2008;116:816–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icart J, Didier J, Dalens M, Chabanon G, Boucays A. Prospective study of epstein barr virus (ebv) infection during pregnancy. Biomedicine. 1981;34:160–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington, D.C: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M. Psychoneuroimmunology of depression: Clinical implications. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:1–16. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Williams JL, Swerdlow DL, Biggerstaff MS, Lindstrom S, Louie JK, Christ CM, Bohm SR, Fonseca VP, Ritger KA, Kuhles DJ, Eggers P, Bruce H, Davidson HA, Lutterloh E, Harris ML, Burke C, Cocoros N, Finelli L, MacFarlane KF, Shu B, Olsen SJ, WNIAHNP H1n1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009;374:451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, O’Connor KA, Deak T, Stark M, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Prior stressor exposure sensitizes lps-induced cytokine production. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:461–476. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JF, Straus SE. Chronic epstein-barr virus infection. Annu Rev Med. 1987;38:195–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.38.020187.001211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer M, Adams D, Castelberg BvB, Glover V. Pregnant women become insensitive to cold stress. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2002;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama N, Tsujimura R, She L, Maehara K, Terao T. Cold-induced stress stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, causing hypertension and proteinuria in rats. J Hypertens. 1997;15:383–389. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay G, Tarcic N, Poltyrev T, Weinstock M. Prenatal stress depresses immune function in rats. Physiol Behav. 1998;63:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00456-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatun S, Kanayama N, Belayet HM, Masui M, Sugimura M, Kobayashi T, Terao T. Induciton of preeclampsia like phenomena by stimulation of sympathetic nerve with cold and fasting stress. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;86:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Loving TJ, Stowell JR, Malarkey WB, Lemeshow S, Dickinson SL, Glaser R. Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1377–1384. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, Malarkey WB, Mercado AM, Glaser R. Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet. 1995;346:1194–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine il-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Lydon J, Seguin L, Goulet L, Kahn SR, McNamara H, Genest J, Dassa C, Chen MF, Sharma S, Meaney MJ, Thomson S, Van Uum S, Koren G, Dahhou M, Lamoureux J, Platt RW. Stress pathways to spontaneous preterm birth: The role of stressors, psychological distress, and stress hormones. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1319–1326. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn BM. Pregnancy and h1n1 flu. JAMA. 2009;301:2542–2542. [Google Scholar]