Abstract

β-Amyloid (Aβ) accumulation and aggregation are hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD). High-resolution three-dimensional (HR-3D) volumetric imaging allows for better analysis of fluorescence confocal microscopy and 3D visualization of Aβ pathology in brain. Early intraneuronal Aβ pathology was studied in AD transgenic mouse brains by HR-3D volumetric imaging. To better visualize and analyze the development of Aβ pathology, thioflavin S staining and immunofluorescence using antibodies against Aβ, fibrillar Aβ, and structural and synaptic neuronal proteins were performed in the brain tissue of Tg19959, wild-type, and Tg19959-YFP mice at different ages. Images obtained by confocal microscopy were reconstructed into three-dimensional volumetric datasets. Such volumetric imaging of CA1 hippocampus of AD transgenic mice showed intraneuronal onset of Aβ42 accumulation and fibrillization within cell bodies, neurites, and synapses before plaque formation. Notably, early fibrillar Aβ was evident within individual synaptic compartments, where it was associated with abnormal morphology. In dendrites, increasing intraneuronal thioflavin S correlated with decreases in neurofilament marker SMI32. Fibrillar Aβ aggregates could be seen piercing the cell membrane. These data support that Aβ fibrillization begins within AD vulnerable neurons, leading to disruption of cytoarchitecture and degeneration of spines and neurites. Thus, HR-3D volumetric image analysis allows for better visualization of intraneuronal Aβ pathology and provides new insights into plaque formation in AD.

β-Amyloid (Aβ) accumulation is a pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (AD), and during the past decade there has been increasing evidence for a critical role for the accumulation of Aβ within neurons in AD. Many studies have shown early intraneuronal Aβ42 accumulation in AD, Down syndrome, and familial Alzheimer's disease (FAD) mutant transgenic rodents.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Importantly, in a triple transgenic mouse, intraneuronal Aβ accumulation was the earliest pathological correlate of abnormalities in long-term potentiation and behavior.19, 20 Thioflavin S (ThS)-positive intraneuronal Aβ fibrils have been described in both APPSLPS1KI and 5XFAD transgenic mice.21, 22 Moreover, neuron loss correlated with the prior appearance of ThS-positive intraneuronal Aβ fibrils in transgenic mice.22 By immunoelectron microscopy, Aβ42 normally localizes to endosomal vesicles. Aβ42 increases with aging, particularly at the outer membranes of multivesicular bodies and smaller endosomal vesicles, and particularly in distal processes and synaptic compartments, where such Aβ accumulation can be directly associated with ultrastructural pathology.6, 23

The development of new imaging software allows for higher resolution image analysis of immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Volume-rendering techniques display two-dimensional stacks of images as 3D volumetric images. High-resolution three-dimensional (HR-3D) volumetric image analysis provides a more complete 3D view of Aβ pathology, leading to new insights into neurite and synapse disruption. In the present study, we provide HR-3D evidence for intracellular Aβ accumulation and fibrillization within synapses, and distal and proximal processes of neurons in CA1 hippocampus. These images demonstrate that before the onset of plaque pathology, intraneuronal Aβ accumulation and fibrillization can develop within soma, dendrites, and even within individual spines, with disruption of synaptic and neuritic cytoarchitecture. These new data support that intraneuronal Aβ provides the nidus for plaque formation.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibody G2-13 recognizes the C-terminus of Aβ42 (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Rabbit polyclonal antibody OC (Millipore) recognizes epitopes common to fibrillar Aβ species, but not nonfibrillar oligomers or natively folded proteins, as characterized biochemically and morphologically by Kayed et al.24 We used ThS to visualize amyloid fibrils. Antibody SMI32 reacts to a nonphosphorylated epitope in neurofilament H and visualizes neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and some thick axons in the central and peripheral nervous systems; thin axons are not labeled (Convance, Princeton, NJ). Mouse monoclonal antibody NeuN specifically recognizes a DNA-binding, neuron-specific protein. NeuN protein distribution is restricted to neuronal nuclei, perikarya, and some proximal processes (Millipore). Vesicular glutamate transporter-1 (VGlut1) guinea pig antibody recognizes glutamatergic synaptic vesicles (Millipore). Postsynaptic density 95 (PSD-95) antibody specifically recognizes the PSD-95 protein located in postsynaptic terminals of excitatory synapses (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Animals

All mouse experiments were compliant with the requirements of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Weill Cornell Medical College and with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Tg19959 mice were obtained from Dr. George Carlson (McLaughlin Research Institute, Great Falls, MT). These mice contain human APP695 with two familial AD mutations (KM670/671NL and V717F) under the control of the hamster PrP promoter.25 Hemizygous male Tg19959 mice were bred to female Thy1.2-YFP-H homozygotes26 to produce double hemizygous Tg19959/YFP-H mice in the F1 generation. Animals were screened for the presence of the human APP695 and Thy1.2-YFP-H transgenes by PCR. Brain sections from Tg19959 (n = 6), wild-type (n = 6), Tg19959-YFP (n = 3), and YFP (n = 3) mice were analyzed.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) at room temperature. After dissection, brains were postfixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 2 hours or overnight. After fixation, brains were cut in 40- or 100-μm thick sections with a vibratome. Sections were kept in storage buffer composed of 30% sucrose and 30% ethylene glycol in PBS at −20°C. Free-floating sections were first incubated in primary antibodies for 24 hours at room temperature, followed by appropriate fluorescent Alexa secondary antibodies (1:200; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 hour at room temperature. For dual and triple label ThS staining, sections were incubated in 0.001% ThS in 70% ethanol for 20 minutes, and then rinsed sequentially with 70%, 95%, and 100% ethanol after immunofluorescent labeling.

Imaging

Images were collected using a Leica SP5 spectral confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL) equipped with HeNe 633 nm/HeNe 543 nm/Argon (458, 476, 488, 514 nm) lasers and with an HCX PL APO CS 63x/NA1.4 oil objective. Two-dimensional images obtained by confocal microscopy were reconstructed into 3D volumetric datasets using Avizo software (Visualization Science Group, Burlington, MA). Isosurfaces were defined individually for each channel from the raw confocal data and rendered as semi-opaque, solid surfaces. During data visualization and exploration, volume-texture visualizations were also used to better appreciate the continuum of intensities in each channel throughout the dataset. This technique computes the opacity and color of each voxel in the 3D volume as a function of the intensities of both channels. Visualization parameters for both isosurface and volume textures were optimized to highlight relevant neuronal structures and pathologies. Movie animations were generated from the Avizo software (Visualization Science Group) to highlight features of interest and to visualize the three-dimensionality of the datasets.

Quantification

Colocalization of Aβ42 with synapses labeled with pre-VGlut1 or PSD-95 markers from confocal acquired images was determined by using a colocalization algorithm (Leica Application Suite 1.8.2 software), which shows only pixels with relative colocalization.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons were made using the Student's t-test with significance placed at P < 0.05. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Results

High-Resolution 3D Volumetric Images Demonstrate Amyloid Fibrils within Neuron Cell Bodies in CA1 Hippocampus

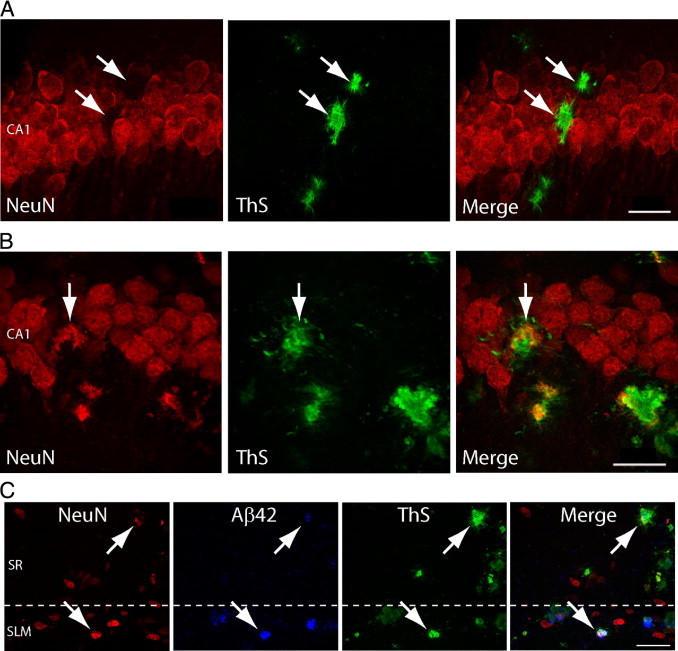

Tg19959 mice over-express double FAD mutant (KM670/671NL and V717F) human APP695 and exhibit plaque formation between 2 and 3 months.25 At 4 months of age these mice show spatial memory deficits and reduced levels of synaptophysin.27At 5 months of age, when these mice show marked Aβ pathology, we noted that some Aβ plaques were located within the CA1 pyramidal cell body layer of the hippocampus. Double labeling with a neuronal marker (NeuN) and ThS at this age showed ThS-positive Aβ plaques within the CA1 pyramidal neuron cell body layer. At this late age, with Aβ appearing in extracellular plaques, there was no direct overlap of ThS with the neuronal marker NeuN (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Thioflavin S (ThS) positive plaques colocalize with neuronal marker NeuN in CA1 hippocampus. A: The 5-month-old Tg19959 mouse reveals ThS (green) positive β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques within the CA1 pyramidal cell body layer. At this age, areas that are labeled with ThS (arrows) are near but not directly colabeled with neuronal marker NeuN (red; arrows). B: In contrast, ThS and NeuN colocalize (merged arrows) in the CA1 pyramidal cell body layer in 3-month-old Tg19959 mice. C: Colocalization (arrows) of ThS, Aβ42 (blue), and NeuN is also seen in synaptic layers of the hippocampus, stratum radiatum, and stratum lacunosum moleculare in 3-month-old Tg19959 mice, supporting that GABAergic interneurons are also a site of ThS positive Aβ fibrils. Scale bars: 25 μm (A, B), 50 μm (C). Animations of the high-resolution three-dimensional reconstructions (B, C) are shown in Supplemental Videos S1 and S2 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), respectively.

To examine whether Aβ plaque-like deposits in CA1 arose from neuron cell bodies, we studied these mice at an earlier stage of plaque pathology at 3 months of age. At this earlier age, HR-3D images now showed colocalization of ThS and NeuN in the CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cell body layer of Tg19959 mice (Figure 1B) (see Supplemental Video S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), supporting that Aβ fibrils are within CA1 neurons at this time. To examine whether ThS and NeuN dual-labeling also occurred outside the CA1 pyramidal cell body layer, we examined the CA1 stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum moleculare. Neuron populations located in these CA1 hippocampal areas are GABAergic interneurons. Triple labeling of 3-month-old Tg19959 mice revealed colocalization of ThS, Aβ42, and NeuN in these layers as well (Figure 1C) (see Supplemental Video S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These data support that at least some Aβ fibrils arise from neuron cell bodies, including glutamatergic pyramidal neurons and GABAergic interneurons, of CA1 hippocampus in Tg19959 transgenic mice.

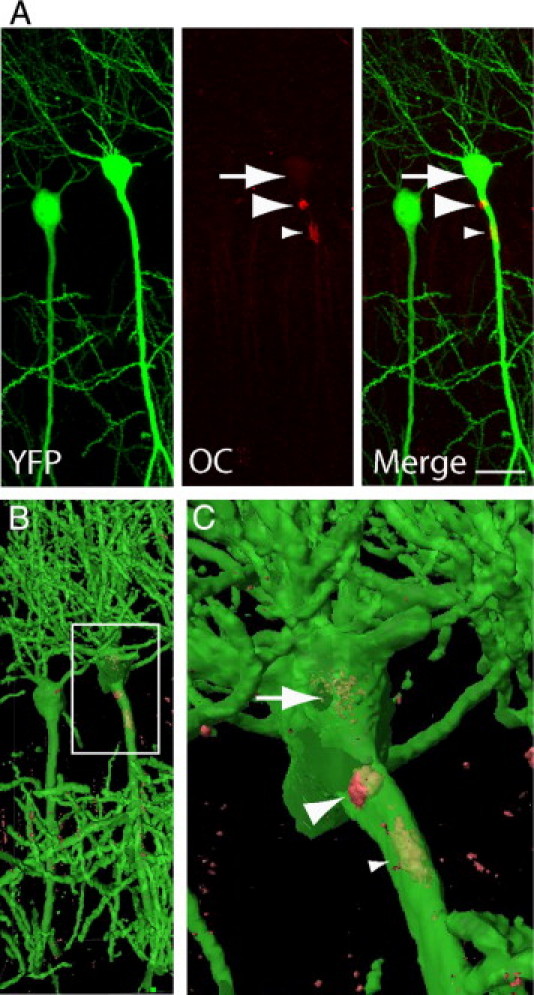

Fibrillar Aβ Species Occur Early within Neurons and Can Traverse the Cell Membrane

To focus on an even earlier stage in the progression of Aβ pathology, we analyzed Tg19959 mice at 2 months of age, which is just before the onset of Aβ plaque pathology in these mice. To better study morphological alterations in neurons and their processes, we crossed Tg19959 mice with YFP mice.26 Tg19959-YFP mice mirror the Aβ pathology of Tg19959 mice and also contain a subset of neurons that are YFP labeled, including cell bodies, axons, dendrites, and spines. These mice do not show ThS positive Aβ plaques at 2 months of age, and therefore we used antibody OC, which has been shown to detect Aβ fibrillar species, as characterized biochemically and morphologically by Kayed et al.24 It should be noted that the characterization of these different Aβ species and their conformations is complex, and moreover that characterization of antibody binding in vitro may not necessarily reflect binding in vivo in the brain. With these caveats in mind, we used antibody OC as a marker for Aβ fibrillar species. It has been described that OC detects fibrillar Aβ species in the absence of ThS staining,24 which we also confirmed (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We found OC antibody labeling in the 2-month-old Tg19959 mice, which were negative for ThS. At 2 months of age, before formation of ThS plaques, OC antibody immunofluorescence colocalized with YFP in proximal and distal processes of pyramidal CA1 neurons in Tg19959-YFP mice (Figure 2A) (see Supplemental Video S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). HR-3D isosurface representation clearly showed that OC antibody labeling was intraneuronal (Figure 2, B and C). For example, fibrillar Aβ species could be seen in the cell body and proximal CA1 apical dendrites. In some HR-3D isosurface images, OC positive fibrillar Aβ species were even seen traversing the plasma membrane of neurites (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Early intracellular fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) species within soma and proximal processes of pyramidal neurons of CA1 hippocampus in Tg19959-YFP mouse brain. A: OC antibody immunofluorescence reveals fibrillar Aβ species in the cell body (arrow) and in proximal areas of apical dendrites (green; arrowheads), where at times they are seen piercing the cell membrane (large arrowhead). B: High-resolution three-dimensional (HR-3D) surface representation of (A). C: Higher magnification of boxed area in B more clearly shows intracellular OC labeling (arrows). Scale bar: 20 μm (A). Animation of the HR-3D reconstruction is shown in Supplemental Video S3 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

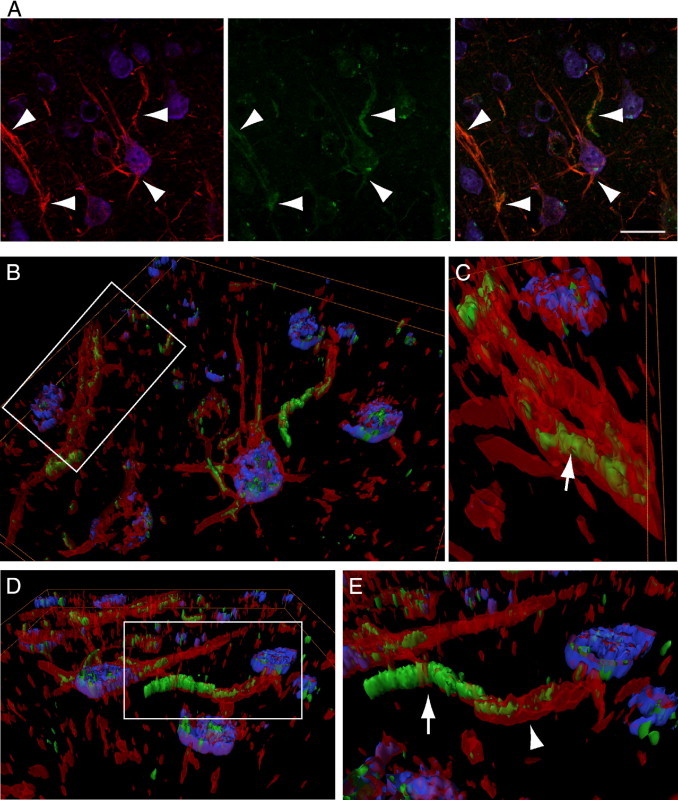

Amyloid Fibrils also Occur within Neurites and Disrupt their Cytoarchitecture

To examine whether intracellular Aβ accumulation and fibrillization disrupts the cytoarchitecture of neurites, brain sections of 3-month-old Tg19959 mice were co-labeled with ThS, neurofilament specific antibody SMI32, and NeuN. We note that ThS is not evident in wild-type mouse brain using these methods (data not shown). HR-3D fluorescence imaging clearly showed the intraneuronal onset of Aβ fibrillization in processes of Tg19959 mouse brains (Figure 3) (see Supplemental Video S4 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) now revealed that increasing intracellular ThS staining intensity correlated with decreasing intraneuronal SMI32 neurofilament labeling.

Figure 3.

Intraneuritic fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) disrupts the cytoarchitecture of dendrites in Tg19959 mice. A: Intracellular thioflavin S (ThS)-positive staining (green) is seen in selective pyramidal neuron cell bodies (blue; NeuN) and neurites (red; arrowheads). B: High-resolution three-dimensional (HR-3D) surface representation of (merged A). C: Rear view of the selected area in (B) shows intracellular ThS-positive staining within a SMI32-positive neurite (red; arrow). D: View from another angle of the surface representation of (A). E: Higher magnification of the box in (D) highlights that increasing ThS staining (arrow) in a neurite correlates with reduced neurofilament SMI32 labeling intensity (arrowhead). Scale bar = 25 μm (A). Animation of the HR-3D reconstruction is shown in Supplemental Video S4 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Fibrillar Aβ Species Occurring within Individual Spines Can Penetrate the Cell Membrane and Are Associated with Dystrophy

Next we focused on whether Aβ accumulation preferentially occurred in presynaptic or postsynaptic compartments of different CA1 hippocampal synaptic layers (see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). At 2 months of age, Tg19959 mice showed 50 ± 5% colocalization of Aβ42 and PSD-95 in the stratum lacunosum moleculare and 52 ± 3% in the stratum radiatum. Colocalization of Aβ42 with the glutamatergic pre-synaptic marker VGlut1 was 28 ± 2% in the stratum lacunosum moleculare and 13 ± 2% in the stratum radiatum. These data indicate that before the onset of plaque pathology, Aβ42 accumulated more in postsynaptic compared to presynaptic terminals of CA1 hippocampus.

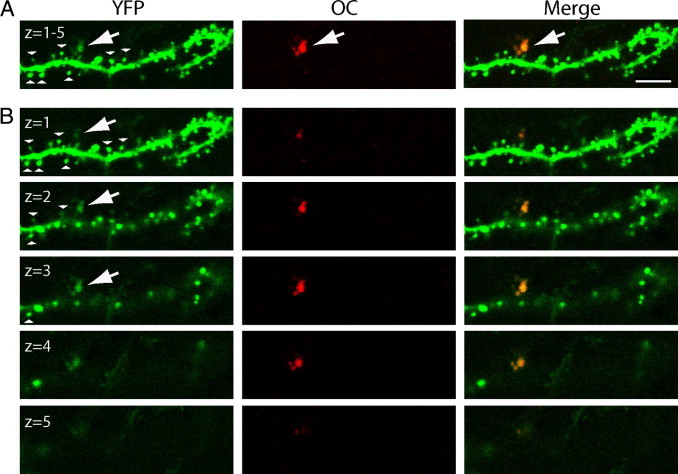

Remarkably, we noted that OC-positive fibrillar Aβ species could be located within individual postsynaptic terminals before the onset of Aβ plaque pathology in 2-month-old Tg19959-YFP mouse sections. Intracellular OC labeling was evident within individual spines in CA1 stratum radiatum (Figure 4) (see Supplemental Video S5 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). OC-negative spines tended to show mainly a mushroom shape compared to OC-positive spines, which showed dystrophic enlargement of the spine head and neck. Interestingly, OC-positive and OC-negative spines could be located in close proximity on the same dendrite. Dystrophic OC-positive spines also showed more diffuse YFP labeling compared to the OC-negative spines with intense YFP labeling.

Figure 4.

Early intracellular fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) species within individual spines in CA1 stratum radiatum. A: Merged image shows the colocalization of OC labeling fibrillar Aβ species (red) with YFP (green) within an individual spine in a dendrite of a 2-month-old Tg19959-YFP mouse (arrow). The representative image shows dystrophic enlargement of the spine with intracellular fibrillar Aβ accumulation compared to spines without fibrillar Aβ accumulation (arrowheads). The image represents a two-dimensional projection of a stack of five consecutive images. B: Sequence of individual images shown in (A). OC negative spines are mostly mushroom shaped and can be located near the OC-positive spine showing dystrophic elongation of the spine head and neck and more diffuse YFP staining. Scale bar = 4 μm (A). Animation of the high-resolution three-dimensional reconstruction is shown in Supplemental Video S5 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

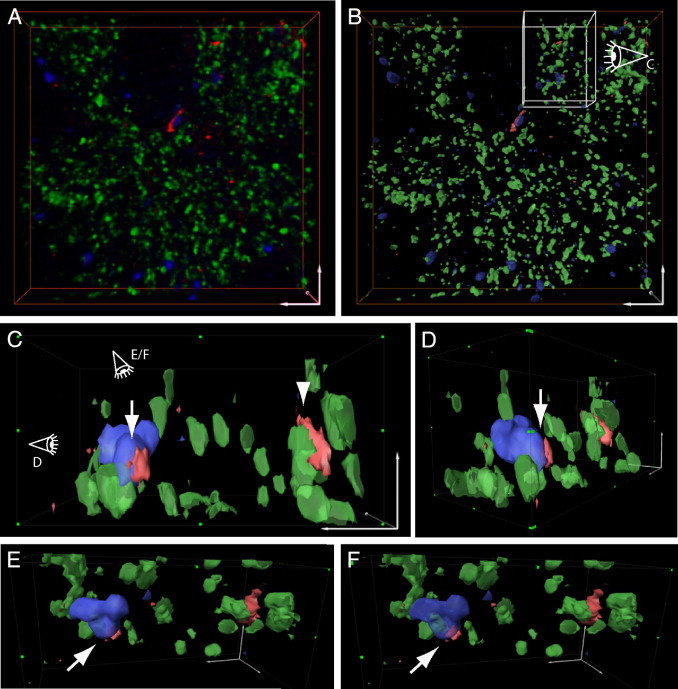

To further examine this synaptic localization of Aβ fibrillar species at a later time point, we co-labeled 3-month-old Tg19959 mouse sections with VGlut1, PSD-95, and OC antibodies. HR-3D surface representations of immunofluorescent-labeled sections showed OC immunoreactivity clearly associated with synapses and within synaptic compartments. Intracellular OC labeling was particularly evident within PSD-95 labeled postsynaptic compartments and also could be seen traversing the cell membrane (Figure 5) (see Supplemental Video S6 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 5.

Fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) within postsynaptic terminals in Tg19959 mice visualized by the high-resolution three-dimensional (HR-3D) surface representation. A: Three-dimensional representation of a stack of images of a section with triple immunofluorescence labeling with vesicular glutamate transporter-1 (VGlut1) (green), postsynaptic density 95 (PSD-95) (blue), and OC (red) antibodies. B: HR-3D surface representation of (A) provides better visualization of synapses. C: Side view of the selected area in (B). OC antibody labeling shows fibrillar Aβ piercing the PSD-95 positive (arrow) compartment adjacent to a glutamatergic pre-synaptic terminal (arrowhead). D: Side view of (C) shows postsynaptic intraneuronal fibrillar Aβ (E, F). Both images show top views of (C). E and F show intracellular fibrillar Aβ within the postsynaptic compartment (arrows). In (F), surface representation intensity of PSD-95 labeling is set to be more transparent than in (E) to more clearly show the intracellular localization of OC labeling. Scale bars: 3 μm (A, B), 1 μm (C–F). Animation of the HR-3D reconstruction is shown in Supplemental Video S6 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Discussion

Many aspects of the origin of plaques and the pathogenic role of Aβ in AD remain unclear.28 Although the Aβ hypothesis has posited that extracellular Aβ aggregates lead to plaque formation,29 increasing evidence supports that the intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ plays a critical role in AD.1, 2, 21, 22, 30, 31 Numerous studies have reported early intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ in AD, Down syndrome, and FAD transgenic rodents.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 16 Intraneuronal Aβ oligomerization16, 23 and fibrillization have also been reported in FAD transgenic models.21, 22 At the same time, immunohistochemical demonstration of intraneuronal Aβ is technically difficult, which has contributed to the slow acceptance for the role of this pool of Aβ in AD. We set out, therefore, to better visualize Aβ pathology in FAD transgenic mouse brains using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy combined with a novel HR-3D imaging technology to better delineate the progression of intraneuronal Aβ pathology within the CA1 area of the hippocampus.

Now we use HR-3D imaging to clearly show that i) intraneuronal Aβ accumulates at early ages before the formation of plaques. This intraneuronal Aβ already forms fibrillar species; ii) within the CA1 region of the hippocampus, these intraneuronal fibrillar species were found within cell bodies of pyramidal and GABAergic neurons, processes, and synaptic structures, especially in postsynaptic compartments; iii) intraneuronal fibrillar Aβ species were seen, even at the level of individual spines where such spines tended to appear less mushroom shaped and were associated with dystrophic enlargement; iv) remarkably, spines containing fibrillar Aβ species could be seen right next to spines devoid of such species; v) within dendrites, increasing accumulation of fibrillar Aβ species was associated with reduction in cytoskeletal proteins; and vi) fibrillar Aβ species were seen piercing the cell membrane. In aggregate, these new data support a scenario in which plaques begin with deposits of intraneuronal Aβ, which then disrupts the cytoarchitecture, pierces the cell membrane, and forms the nidus for extracellular plaques.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG027140 and AG028174 to G.K.G., and AG20729 to M.T.L.), and the Strong Research Environment Multipark (Multidisciplinary research in Parkinson's disease at Lund University).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.045.

Supplementary data

OC antibody detects fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) species, even in the absence of thioflavin S (ThS) staining. Merged image shows the colocalization of fibrillar Aβ OC labeling (red) with ThS (green) within the pyramidal cell body layer (blue) of CA1 hippocampus of a 3-month-old Tg19959 mouse. OC labeling, however, is detected in a larger area surrounding the ThS staining. The wild-type mouse does not show any ThS staining or OC labeling. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Early postsynaptic β-amyloid (Aβ)42 accumulation in CA1 hippocampus. A: Representative images of double immunofluorescence labeling for Aβ42 (red) and the glutamatergic pre-synaptic marker vesicular glutamate transporter-1 (VGlut1) (green) in stratum radiatum (SR) and stratum lacunosum moleculare (SLM) show a higher amount of colocalization in SLM compared to SR in a representative image of a 2-month-old Tg19959 mouse section. B: Representative images of double immunofluorescence labeling for Aβ42 (red) and the postsynaptic marker, postsynaptic density 95 (PSD-95) (green), show no significant differences in their level of colocalization in the SR and SLM. C: The bar graph shows a significantly higher degree of colocalization of Aβ42 with the postsynaptic marker PSD-95 (50 ± 5% in SLM; 52 ± 3% in SR) than with the pre-synaptic marker VGlut1 (28 ± 2% in SLM; 13 ± 2% in SR) (*P < 0.05, n = 3; **P < 0.005, n = 3). Scale bar = 10 μm (A, B).

CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neuron as the origin of a thioflavin S (ThS)-positive β-amyloid (Aβ) plaque.

β-amyloid (Aβ)42, NeuN, and thioflavin S (ThS) colocalization in the CA1 hippocampal synaptic layer.

Intraneuronal fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) in Tg19959-YFP mice at 2 months of age.

Intraneuritic thioflavin S (ThS) labeling correlates with reduced neurofilament labeling.

Dystrophic enlargement of spine with intracellular fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation.

Intracellular fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation within postsynaptic terminals.

References

- 1.Gouras G.K., Tsai J., Naslund J., Vincent B., Edgar M., Checler F., Greenfield J.P., Haroutunian V., Buxbaum J.D., Xu H., Greengard P., Relkin N.R. Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in human brain. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64700-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Andrea M.R., Nagele R.G., Wang H.Y., Peterson P.A., Lee D.H. Evidence that neurones accumulating amyloid can undergo lysis to form amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Histopathology. 2001;38:120–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gyure K.A., Durham R., Stewart W.F., Smialek J.E., Troncoso J.C. Intraneuronal abeta-amyloid precedes development of amyloid plaques in Down syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:489–492. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0489-IAAPDO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirths O., Multhaup G., Czech C., Blanchard V., Moussaoui S., Tremp G., Pradier L., Beyreuther K., Bayer T.A. Intraneuronal Abeta accumulation precedes plaque formation in beta-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 double-transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett. 2001;306:116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori C., Spooner E.T., Wisniewsk K.E., Wisniewski T.M., Yamaguch H., Saido T.C., Tolan D.R., Selkoe D.J., Lemere C.A. Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in Down syndrome brain. Amyloid. 2002;9:88–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi R.H., Milner T.A., Li F., Nam E.E., Edgar M.A., Yamaguchi H., Beal M.F., Xu H., Greengard P., Gouras G.K. Intraneuronal Alzheimer abeta42 accumulates in multivesicular bodies and is associated with synaptic pathology. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cataldo A.M., Petanceska S., Terio N.B., Peterhoff C.M., Durham R., Mercken M., Mehta P.D., Buxbaum J., Haroutunian V., Nixon R.A. Abeta localization in abnormal endosomes: association with earliest Abeta elevations in AD and Down syndrome. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lord A., Kalimo H., Eckman C., Zhang X.Q., Lannfelt L., Nilsson L.N. The Arctic Alzheimer mutation facilitates early intraneuronal Abeta aggregation and senile plaque formation in transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knobloch M., Konietzko U., Krebs D.C., Nitsch R.M. Intracellular Abeta and cognitive deficits precede beta-amyloid deposition in transgenic arcAbeta mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1297–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Broeck B., Vanhoutte G., Pirici D., Van Dam D., Wils H., Cuijt I., Vennekens K., Zabielski M., Michalik A., Theuns J., De Deyn P.P., Van der Linden A., Van Broeckhoven C., Kumar-Singh S. Intraneuronal amyloid beta and reduced brain volume in a novel APP T714I mouse model for Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philipson O., Lannfelt L., Nilsson L.N. Genetic and pharmacological evidence of intraneuronal Abeta accumulation in APP transgenic mice. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3021–3026. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aho L., Pikkarainen M., Hiltunen M., Leinonen V., Alafuzoff I. Immunohistochemical visualization of amyloid-beta protein precursor and amyloid-beta in extra- and intracellular compartments in the human brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:1015–1028. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belinson H., Kariv-Inbal Z., Kayed R., Masliah E., Michaelson D.M. Following activation of the amyloid cascade, apolipoprotein E4 drives the in vivo oligomerization of amyloid-beta resulting in neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:959–970. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espana J., Gimenez-Llort L., Valero J., Minano A., Rabano A., Rodriguez-Alvarez J., LaFerla F.M., Saura C.A. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid accumulation in the amygdala enhances fear and anxiety in Alzheimer's disease transgenic mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandy S., Simon A.J., Steele J.W., Lublin A.L., Lah J.J., Walker L.C., Levey A.I., Krafft G.A., Levy E., Checler F., Glabe C., Bilker W.B., Abel T., Schmeidler J., Ehrlich M.E. Days to criterion as an indicator of toxicity associated with human Alzheimer amyloid-beta oligomers. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:220–230. doi: 10.1002/ana.22052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leon W.C., Canneva F., Partridge V., Allard S., Ferretti M.T., Dewilde A., Vercauteren F., Atifeh R., Ducatenzeiler A., Klein W., Szyf M., Alhonen L., Cuello A.C. A novel transgenic rat model with a full alzheimer's-like amyloid pathology displays pre-plaque intracellular amyloid-beta-associated cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:113–126. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nunomura A., Tamaoki T., Tanaka K., Motohashi N., Nakamura M., Hayashi T., Yamaguchi H., Shimohama S., Lee H.G., Zhu X., Smith M.A., Perry G. Intraneuronal amyloid beta accumulation and oxidative damage to nucleic acids in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:731–737. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomiyama T., Matsuyama S., Iso H., Umeda T., Takuma H., Ohnishi K., Ishibashi K., Teraoka R., Sakama N., Yamashita T., Nishitsuji K., Ito K., Shimada H., Lambert M.P., Klein W.L., Mori H. A mouse model of amyloid beta oligomers: their contribution to synaptic alteration, abnormal tau phosphorylation, glial activation, and neuronal loss in vivo. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4845–4856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5825-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oddo S., Caccamo A., Shepherd J.D., Murphy M.P., Golde T.E., Kayed R., Metherate R., Mattson M.P., Akbari Y., LaFerla F.M. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billings L.M., Oddo S., Green K.N., McGaugh J.L., LaFerla F.M. Intraneuronal Abeta causes the onset of early Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2005;45:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casas C., Sergeant N., Itier J.M., Blanchard V., Wirths O., van der Kolk N., Vingtdeux V., van de Steeg E., Ret G., Canton T., Drobecq H., Clark A., Bonici B., Delacourte A., Benavides J., Schmitz C., Tremp G., Bayer T.A., Benoit P., Pradier L. Massive CA1/2 neuronal loss with intraneuronal and N-terminal truncated Abeta42 accumulation in a novel Alzheimer transgenic model. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1289–1300. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63388-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oakley H., Cole S.L., Logan S., Maus E., Shao P., Craft J., Guillozet-Bongaarts A., Ohno M., Disterhoft J., Van Eldik L., Berry R., Vassar R. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi R.H., Almeida C.G., Kearney P.F., Yu F., Lin M.T., Milner T.A., Gouras G.K. Oligomerization of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid within processes and synapses of cultured neurons and brain. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3592–3599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5167-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kayed R., Head E., Sarsoza F., Saing T., Cotman C.W., Necula M., Margol L., Wu J., Breydo L., Thompson J.L., Rasool S., Gurlo T., Butler P., Glabe C.G. Fibril specific, conformation dependent antibodies recognize a generic epitope common to amyloid fibrils and fibrillar oligomers that is absent in prefibrillar oligomers. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li F., Calingasan N.Y., Yu F., Mauck W.M., Toidze M., Almeida C.G., Takahashi R.H., Carlson G.A., Flint Beal M., Lin M.T., Gouras G.K. Increased plaque burden in brains of APP mutant MnSOD heterozygous knockout mice. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1308–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng G., Mellor R.H., Bernstein M., Keller-Peck C., Nguyen Q.T., Wallace M., Nerbonne J.M., Lichtman J.W., Sanes J.R. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron. 2000;28:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dumont M., Wille E., Stack C., Calingasan N.Y., Beal M.F., Lin M.T. Reduction of oxidative stress, amyloid deposition, and memory deficit by manganese superoxide dismutase overexpression in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2009;23:2459–2466. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-132928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gouras G.K., Tampellini D., Takahashi R.H., Capetillo-Zarate E. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid accumulation and synapse pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:523–541. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0679-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardy J., Selkoe D.J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheng J.G., Bora S.H., Xu G., Borchelt D.R., Price D.L., Koliatsos V.E. Lipopolysaccharide-induced-neuroinflammation increases intracellular accumulation of amyloid precursor protein and amyloid beta peptide in APPswe transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:133–145. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(03)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Andrea M., Nagele R. Morphologically distinct types of amyloid plaques point the way to a better understanding of Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Biotech Histochem. 2010;85:133–147. doi: 10.3109/10520290903389445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

OC antibody detects fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) species, even in the absence of thioflavin S (ThS) staining. Merged image shows the colocalization of fibrillar Aβ OC labeling (red) with ThS (green) within the pyramidal cell body layer (blue) of CA1 hippocampus of a 3-month-old Tg19959 mouse. OC labeling, however, is detected in a larger area surrounding the ThS staining. The wild-type mouse does not show any ThS staining or OC labeling. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Early postsynaptic β-amyloid (Aβ)42 accumulation in CA1 hippocampus. A: Representative images of double immunofluorescence labeling for Aβ42 (red) and the glutamatergic pre-synaptic marker vesicular glutamate transporter-1 (VGlut1) (green) in stratum radiatum (SR) and stratum lacunosum moleculare (SLM) show a higher amount of colocalization in SLM compared to SR in a representative image of a 2-month-old Tg19959 mouse section. B: Representative images of double immunofluorescence labeling for Aβ42 (red) and the postsynaptic marker, postsynaptic density 95 (PSD-95) (green), show no significant differences in their level of colocalization in the SR and SLM. C: The bar graph shows a significantly higher degree of colocalization of Aβ42 with the postsynaptic marker PSD-95 (50 ± 5% in SLM; 52 ± 3% in SR) than with the pre-synaptic marker VGlut1 (28 ± 2% in SLM; 13 ± 2% in SR) (*P < 0.05, n = 3; **P < 0.005, n = 3). Scale bar = 10 μm (A, B).

CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neuron as the origin of a thioflavin S (ThS)-positive β-amyloid (Aβ) plaque.

β-amyloid (Aβ)42, NeuN, and thioflavin S (ThS) colocalization in the CA1 hippocampal synaptic layer.

Intraneuronal fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) in Tg19959-YFP mice at 2 months of age.

Intraneuritic thioflavin S (ThS) labeling correlates with reduced neurofilament labeling.

Dystrophic enlargement of spine with intracellular fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation.

Intracellular fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation within postsynaptic terminals.