Abstract

Activation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway is associated with poor response to doxorubicin-containing regimens, such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin), vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP), in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, interferes with ER responses and improves survival in patients with aggressive hematologic malignant tumors, although its use in DLBCL patients remains controversial. The 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78), also known as immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein (BiP), is an ER stress sensor involved in the resistance to doxorubicin and bortezomib, but its role in the response to chemotherapy in DLBCL has not been explored before. We show that high BiP/GRP78 expression is related to worse overall survival (median overall survival, 5.2 versus 3.4 years). Moreover, cell death after R-CHOP in DLCBL cell lines is associated with decreased BiP/GRP78 expression. Conversely, DLBCL cell lines are primarily resistant to bortezomib, probably owing to BiP/GRP78 overexpression. Small-interfering RNA silencing of BiP/GRP78 renders all cell lines sensitive to bortezomib. R-CHOP with bortezomib (R-CHOP-BZ) reduces BiP/GRP78 expression and overcomes bortezomib resistance, mimicking the small-interfering RNA silencing of BiP/GRP78. Accordingly, R-CHOP-BZ is the most effective treatment, providing a rationale for the use of this combinational therapy to improve DLBCL patient survival. Moreover, this study provides preclinical evidence that the germinal center B-cell–like subtype DLBCL is sensitive to bortezomib combined with immunochemotherapy.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most frequent non-Hodgkin lymphoma.1 The chemotherapeutic drugs rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin), vincristine, and prednisone (collectively known as R-CHOP) are currently the standard regimen for patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL. Immunochemotherapy is effective in treating aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but there are still a substantial number of DLBCL patients for whom the standard treatment is insufficiently effective or has major toxic effects,2, 3, 4 underscoring the biological heterogeneity of this disease. The combination of R-CHOP with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (R-CHOP-BZ) is a clinically acceptable regimen,5, 6 although whether the addition of bortezomib may improve the efficacy of immunochemotherapy in DLBCL patients is still under investigation.6, 7, 8 Moreover, the differential efficacy of bortezomib and immunochemotherapy related to the molecular subtypes of DLBCL is still controversial.6, 8, 9, 10 Bortezomib induces cell death by disrupting the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress responses in multiple myeloma11, 12 and in mantle cell lymphoma.13, 14, 15 Moreover, preclinical studies demonstrate that bortezomib induces apoptosis and sensitizes tumor cells to chemotherapy and radiation.16

The ER stress response is involved in aggressive phenotype and chemoresistance in many tumor types, including B-cell lymphomas.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 The 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78), also known as immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein (BiP), is an essential regulator of ER homeostasis. BiP/GRP78 controls the activation of the ER stress sensors and initiates the ER stress response.25 Therefore, BiP/GRP78 expression is widely used as a marker for ER stress.26, 27 Because of its antiapoptotic role, the expression of BiP/GRP78 is important for tumor cell survival under ER stress.28 Nevertheless, the role of BiP/GRP78 in B-cell lymphomas remains to be determined.29, 30

Recent studies show that BiP/GRP78 confers resistance against doxorubicin-mediated apoptosis.26 Therefore, the overexpression of BiP/GRP78 in tumors may be predictive of resistance to doxorubicin-containing regimens, such as R-CHOP.30, 31, 32 The aims of this study were to analyze the prognostic significance of BiP/GRP78 expression in DLBCL patients and to evaluate the possible role of BiP/GRP78 in the response of DLBCL cells to R-CHOP– and to R-CHOP-BZ–based regimens.

Materials and Methods

Samples and Patients

Tumor specimens from 119 patients diagnosed as having DLBCL after 2002 who were treated with standard R-CHOP were retrieved from the files of the Laboratory of Pathology of the Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain. In 60 of these patients, gene expression profiles were available, and 52 tumors were classified as germinal center B-cell–like (GCB)24 or activated B-cell–like (ABC)8 subtypes (see below), whereas 8 of them (13%) remained DLBCL unclassified. Approval for these studies was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Clinic. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All cases were reviewed by at least two pathologists (A.M., E.C.) and reclassified following the 2008 World Health Organization classification.1 The main clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The patients had a median age of 60 years, 53% were male and 47% female, 53% presented with advanced stage disease, 52% had extranodal involvement (including bone marrow in 12.5%), and 39% registered high serum lactate dehydrogenase levels (>450 IU/L). The distribution according to the International Prognostic Index (IPI) was as follows: low risk, 29%; low/intermediate risk, 32%; high/intermediate risk, 18%; and high risk, 21%. Staging and restaging maneuvers were the standard. All patients had assessable response, and 29 (72.5%) achieved a complete response.33 After a median follow-up of 4.6 years for surviving patients, 16 had died, with a 5-year overall survival of 56% (95% CI, 40% to 72%).

Table 1.

Main Clinical Features of 52 DLBCL Patients Classified by Gene Expression Profiles as ABC and GCB Subtypes

| Feature | Finding |

|---|---|

| Sex, M/F | 29/23 |

| Age, median (range), years | 60 (17–84) |

| B-symptoms, % | 54 |

| Extranodal involvement, % | 52 |

| Advanced-stage disease, % | 53 |

| Positive bone marrow test result, % | 12.5 |

| High serum lactate dehydrogenase level, % | 39 |

| IPI risk, % | |

| Low | 29 |

| Low/intermediate | 32 |

| High/intermediate | 18 |

| High | 21 |

F, female; M, male; IPI, International Prognostic Index.

IHC and Immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded whole tissue sections and tissue microarray sections. A rabbit monoclonal antibody (C50B12) produced against a synthetic peptide corresponding to residues surrounding the Gly584 of human BiP/GRP78 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) was used. Briefly, paraffin sections on silane-coated slides were developed in a fully automated immunostainer (Bond Max; Vision Biosystems, Mount Waverley, Australia). Antigen retrieval was performed for 20 minutes in Bond ER1 Buffer solution (Vision Biosystems) followed by 2 hours of incubation with primary antibody (1:1000) at room temperature and 30 minutes of Bond Refine Polymer (Vision Biosystems). Diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used for 8 minutes as a chromogen.

Double chromogenic immunostaining was performed by using mouse anti-human human IRF4 (Mum1p) (1:200; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), rabbit anti-human PRDM1 (Blimp1) polyclonal (Atlas Antibodies, Stockholm, Sweden), and anti-human BiP/GRP78 as primary antibodies. Sequential primary incubations and sequential detections with a peroxidase-based detection were used. DAB for IRF4 and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC+; Dako) for BiP/GRP78 were used as chromogen in a BondMax autostainer (Vision Biosytems).

Double immunofluorescence was performed on cytospins of cell suspensions obtained after repetitive squirt of a reactive lymph node with RPMI 1640 culture medium using a fine needle as previously described.34 An enrichment of B cells was performed by CD19 labeled to magnetic beads (130-050-30; Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to manufacturer's recommendations and positive sorting using the Automacs system (Miltenyi Biotech). Thereafter, multiples cytospins were obtained for immunofluorescence. An anti-BiP/GRP78 antibody was incubated as described above. After washing, the slides were then incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with a goat anti-rabbit antibody labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc, West Grove, PA). The slides were rinsed again and a secondary incubation with anti-Calnexin antibody (Clone H-70; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was performed for 2 hours at room temperature. A goat anti-mouse antibody labeled with sulforhodamine 101 acid chloride (Texas Red; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc) was applied for 1 hour in the dark and mounted with an aqueous mounting media that contains DAPI as nuclear counterstain (Fluorescent Mounting Medium; Dako). Samples were visualized on a Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus GmbH, Hamburg Germany) by means of DP70 cooled CCD camera (Olympus) with the use of CellB̂ imaging software (Olympus).

Cell Lines, Culture Conditions, and Treatments

The 4 human DLBCL cell lines used in this study (SUDHL-4, SUDHL-6, SUDHL-16, and OCI-LY8) were grown in RPMI 1640 or Dulbecco's minimal essential medium, supplemented with 10% to 20% fetal calf serum, 2 mmol/L glutamine (GIBCO, Gaithersburg, MD), and 50 μg/mL of penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO). Cells were incubated for 8 to 16 hours with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, either alone or in combination with R-CHOP (R-CHOP-BZ). For the R-CHOP combinations, cells were supplemented with nondescomplemented serum. Cyclophosphamide was used at a concentration ranging from 0.01 to 25 nmol/L, doxorubicin from 0.01 to 100 nmol/L, vincristine from 0.5 to 100 nmol/L, prednisone from 1 to 50 μmol/L, rituximab at 50 μg/mL, and bortezomib from 5 to 10 nmol/L. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The sources and dilutions of the drugs used in the study are specified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Drugs, Doses, and Source Used in the Study

| Drug | Doses | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | 50 μg/mL | Roche, Basel, Switzerland |

| Cyclophosphamide | 0.01 nmol/L-0.5 nmol/L-25 nmol/L | ASTAMedica, Frankfurt, Germany |

| Doxorubicin | 0.01 nmol/L-1 nmol/L-100 nmol/L | Pfizer, New York, NY |

| Vincristine | 0.5 nmol/L-10 nmol/L-100 nmol/L | STADA, Barcelona, Spain |

| Prednisone | 1 μmol/L-10 μmol/L-50 μmol/L | Pfizer |

| Bortezomib | 5 nmol/L-10 nmol/L | Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA |

Cell viability was analyzed by quantification of phosphatidylserine exposure by double staining with Annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate and propidium iodide (Bender Medsystems Gmbh, Vienna, Austria). A minimum of 104 cells per sample were acquired in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and the labeled populations were analyzed with the Paint-A-Gate software (Becton Dickinson).

RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA for real-time PCR was extracted using RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and the RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen). Afterward, it was reverse transcribed using 1 μg of total RNA and the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). The product was amplified and quantified using complementary DNA TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and TaqMan Gene Expression Assay for BIP/HSPA5 (Hs99999174_m1) in an ABI Prism 7900HT Fast Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantification of gene expression was performed as described in the Taqman user's manual, and the expression levels were analyzed with the 2-ΔΔCt method using human β-glucuronidase (Hs999999058_m1) as endogenous control and the Universal Human Reference RNA (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as calibrator.

Microarray Gene Expression Profiling

Total RNA was extracted with the DNA/RNA Mini kit following the manufacturer's recommendations (Qiagen). RNA integrity was examined with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), and only high-quality RNA samples were hybridized to HU133plus2.0 GeneChips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), according to Affymetrix standard protocols. The analysis of the scanned images and the determination of the signal value for each probe set of the array were obtained with the GeneChip Operating Software (Affymetrix). The data normalization was performed by the global scaling method with the target intensity set at 150. We used the bayesian compound covariate predictor of the ABC/GCB DLBCL previously described by Lenz et al.35 All samples predicted as ABC DLBCL with greater than 90% were called ABC DLBCL. The samples that showed less than 10% of probability of being called ABC DLBCL were classified as GCB DLBCL.

RNA Interference Assay

For transient down-regulation assays, cell lines were electroporated in a Nucleofector device (Amaxa-Lonza, Cologne, Germany) with two different sets of small-interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting the exons 1 (s6980) and 3 (s6981) of the BiP/GRP78 gene (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). As control, irrelevant nonsilencing siRNA (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′) was used as previously described.36 Briefly, 7 × 106 cells were resuspended in 100 μL of Ingenio Electroporation Solution (Mirius, Madison, WI) containing 0.5 or 2.5 μmol/L double-stranded siRNA and electroporated using the Nucleofector program O-017. Cells were then transferred to culture plates and cultivated at a final concentration of 3 × 106 cells/mL for 3 hours. Then, cells were transferred to a new plate and cultured at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL for 3 hours. The electroporation efficiency ranged from 81.2% to 99.3% for SUDHL16 and from 69.7% to 79.6% in OCI-LY8. Cytotoxicity due to electroporation process was low in both cell lines, approximately 20%. The nontargeting (scramble) siRNA (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′; Qiagen) was used as a negative control.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot

Western blot was performed as described previously.17 Briefly, exponentially growing cells (approximately 106 cells/mL) were lysed in a nondenaturing detergent (M-PER; Pierce, Rockford, IL) containing protease inhibitors (Complete Mini; Roche, Manheim, Germany) and phosphatase inhibitors (Cocktails 1 and 2; Sigma, St Louis, MO). The protein content was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Identical amounts of total extracted protein were heated 10 minutes at 70°C in NuPAGE LDS Sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and separated by electrophoresis on 4% to 20% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gradient gels (Novex NuPAGE). After transference to a 0.45-μm pore size nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), the immunoblotting was performed as follows. The membrane was blocked 2 hours at room temperature in 50 mmol/L Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6) with 0.05% Tween-20 containing 5% nonfat dry milk. The nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with a rabbit anti-BiP/GRP78 (Cell Signaling Technology) and mouse anti-α-tubulin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) as a loading control. Binding was detected using a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England) and an enhanced chemiluminiscence Supersignal WestPico detection kit (Pierce). Visualization and image analysis were performed in a mini LAS-4000 camera system (Fuji Photo Film, Minato-Ku, Tokyo, Japan) and Multi GAUGE V2.0 software (Fuji Photo Film). After scanning blots, densities were determined using the image analysis software ImageJ 1.144 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Measurements were normalized to α-tubulin.

Statistical Analysis

The expression of BiP/GRP78 was recorded and analyzed for the prognostic significance. Categorical data were compared using the χ2 or Fisher's exact test (two-sided P value), whereas for ordinal data nonparametric tests were used. To select the optimal cutoff of the quantitative expression for BiP/GRP78 predicting survival, a maximally selected rank statistics test37 was performed using the Maxstat package (R statistical package, v. 2.8.1; Maxstat, Vienna, Austria), and the cutoff was ultimately delimitated by the Kaplan-Meier method and the curves compared by the log-rank test.38

Results

The ER Stress Sensor BiP/GRP78 Is Expressed in Reactive Tissues and DLBCL with Prognostic Implications

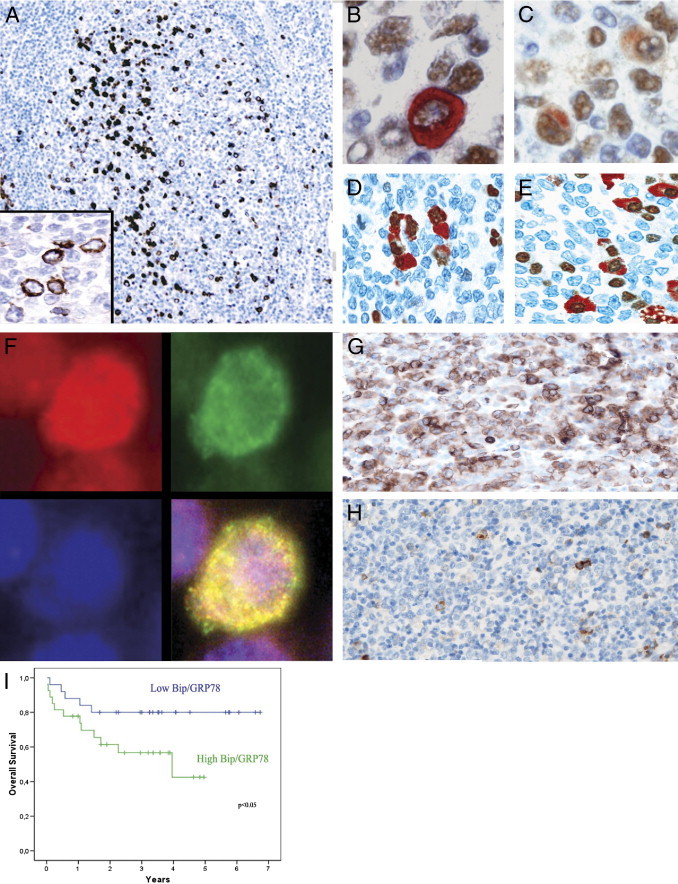

The pattern and distribution of BiP/GRP78 expression in reactive lymphoid tissues was assessed by immunohistochemistry using a rabbit polyclonal antibody on paraffin-embedded tissue sections. BiP/GRP78 was variably expressed in the cytoplasm of germinal center cells mostly in the light zones, where cells devoted to a postgerminal center differentiation program are located (Figure 1F–G). Plasma cells were also strongly positive (data not shown). To further characterize BiP/GRP78-expressing cells in reactive tissues, we performed dual-label immunohistochemistry using antibodies to two transcription factors, Blimp1 and IRF4, important in late B-cell differentiation. BiP/GRP78 was variably expressed in a subset of Blimp1-positive (Figure 1, B and C) and IRF4-positive (Figure 1D) GCBs thought to be committed to plasma cell or memory B-cell differentiation in the light zones of germinal centers. IRF4-positive plasma cells were also strongly positive (Figure 1E). This finding is consistent with the known role for BiP/GRP78 in immunoglobulin secretion in plasma cells. Notably, although the subcellular distribution of BiP/GRP78 is controversial,39, 40, 41 only a clear cytoplasmic staining was observed in reactive lymphoid cells. To explore whether BiP/GRP78 was expressed in the ER of other intracytoplasmic organelles, we then analyzed its localization by immunofluorescence in a purified B-cell suspension from a reactive lymph node. BiP/GRP78 was found in the perinuclear region, coexpressed together with an ER stably resident protein, calnexin, demonstrating ER localization in both reactive (Figure 1F) and neoplastic B cells (data not shown).

Figure 1.

BiP/GRP78 expression in reactive lymphoid tissues and tumors. A: In the light zones of secondary lymphoid follicles clusters of cytoplasmic BiP/GRP78, positive cells can be easily identified (BiP/GRP78, original magnification, ×10). Inset: Detail of the cytoplasmic positivity of BiP/GRP78 (original magnification, ×60). Double staining immunohistochemistry for Blimp1 (DAB, brown) and BiP/GRP78 (AEC+, red) (B–C) and for IRF4 (DAB, brown) and BiP/GRP78 (AEC+, red) (D–E) confirm the expression of BiP/GRP78 in GCB subtype cells committed to a postgerminal center differentiation (original magnification, ×60) and in plasma cells (E). F: Immunofluorescence from a cell suspension of purified reactive B cells demonstrates that BiP/GRP78 colocalizes with the ER marker Calnexin (merge in the lower right: original magnification, ×100 under oil, yellow indicates colocalization). Calnexin is shown in red in the upper left (Texas Red, original magnification, ×100 under oil), BiP/GRP78 is shown in green in the upper right (fluorescein isothiocyanate, original magnification, ×100 under oil), nuclear counterstain in blue in the lower left (DAPI, original magnification, ×100 under oil). G: A representative case of DLBCL with strong expression of BiP/GRP78 (BiP/GRP78, original magnification, ×40). H: DLBCL with weak cytoplasmic expression of BiP/GRP78 in isolated tumor cells (BiP/GRP78, original magnification, ×40). I: Overall survival of DLBCL patients regarding BiP/GRP78 gene expression (quartiles 1 to 2 versus quartiles 3 to 4).

The role of BiP/GRP78 in DLBCL patients is unknown; therefore; we analyzed BiP/GRP78 mRNA and protein expression in a series of 119 DLBCL patients. BiP/GRP78 was also variably expressed in DLBCL tumor cells, always as a cytosolic protein (Figure 1, G and H). To select the optimal cutoff for the quantitative expression for BiP/GRP78 predicting survival, a maximally selected rank statistics test was performed. A case was considered positive if more than 20% (50th percentile; interquartile range, 0% to 60%) of tumor cells expressed BiP/GRP78. BiP/GRP78 was expressed in 91 of 119 DLBCL patients (76.4%) (Figure 1, G and H). No correlation was observed between BiP/GRP78 protein expression and GCB or ABC subtypes (P = 0.852) by gene expression profile or overall survival (P = 0.972).

We also analyzed BiP/GRP78 mRNA expression by assembling microarray data sets from 52 patients of the 119 patients described above; all of them had available clinical data, and all were homogenously treated with R-CHOP. BiP/GRP78 mRNA expression in tumors was a continuum [mean, 4953.8 ± 1807.6 relative units (RU); range, 2285 to 11,129.2 RU]. No relationship was observed between BiP/GRP78 expression and the clinical characteristics at diagnosis, including age, bulky disease, stage, lactate dehydrogenase level, β2-microglobulin, primary extranodal presentation, and IPI. Interestingly, we observed no differences in BiP/GRP78 mRNA expression between tumors of GCB and ABC types by gene expression profiling (see Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Moreover, no correlation was found between BiP/GRP78 expression by protein and mRNA (P = 0.873). More importantly, patients with higher levels of BiP/GRP78 mRNA (50th to 100th percentile) showed a poorer outcome (P = 0.048) in terms of overall survival, with a median overall survival of 3.4 and 5.2 years for patients with high and low levels, respectively (Figure 1I).

BiP/GRP78 Is Expressed in DLBCL Cell Lines and Down-Regulated by Standard R-CHOP Immunochemotherapy

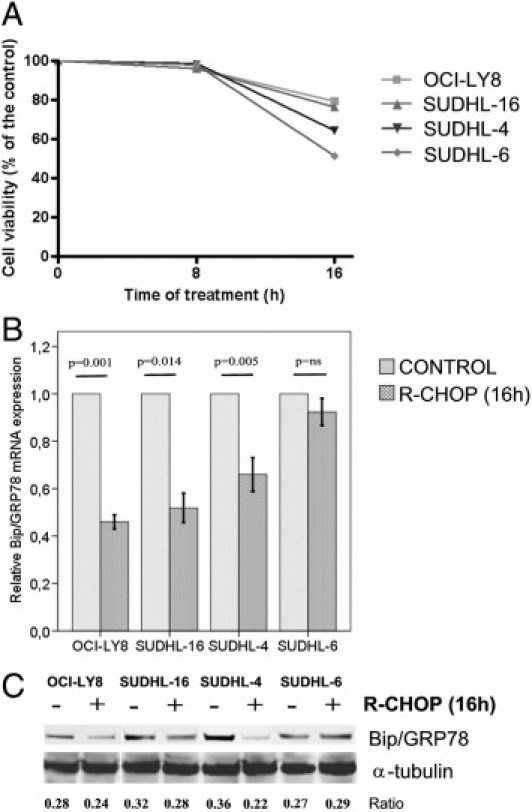

To analyze the specific value of BiP/GRP78 in the efficiency of the standard immunochemotherapy in DLBCL, we first treated the DLBCL cell lines OCI-LY8, SUDHL-4, SUDHL-6, and SUDHL-16 with each of the following drugs alone using previously described conditions: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, rituximab, and bortezomib.42, 29 Three different doses were used for each drug (Table 2), and the cell death rates for each drug ranged from 0% to 35% at 24 hours (data not shown). To reproduce in vitro the conditions for R-CHOP combination, the minimal dose of each drug was selected, as previously described,29, 43 and the final doses are summarized in Table 2. No cytotoxicity was observed after 8 hours of R-CHOP, whereas the cytocidal effect at 16 hours ranged from 20% in OCI-LY8 to 49% in SUDHL6 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Cell survival and BiP/GRP78 gene expression after R-CHOP treatment. A: After 16 hours of treatment cell death rates ranged from 20% in OCI-LY8 to 49% in SUDHL6 cells. BiP/GRP78 expression is down-regulated in both mRNA (B) and protein (C) in DLBCL cell lines after R-CHOP. Numbers represent the ratio of BiP/GRP78 and α-tubulin optical density. Error bars represent 2 SDs.

We then analyzed the impact of immunochemotherapy on BiP/GRP78 mRNA and protein expression. In untreated cells, BiP/GRP78 levels were variable among the different cell lines. SUDHL-4 (2.86 RU) and SUDHL-16 (3.78 RU) had higher BiP/GRP78 expression than SUDHL-6 (0.95 RU) and OCI-Ly8 (1.37 RU) (data not shown). Moreover, as observed in patient samples, the cell line expressing the lowest BiP/GRP78 mRNA basal levels, SUDHL-6, was the most sensitive to R-CHOP. Interestingly, after the standard treatment with R-CHOP, a marked decrease in BiP/GRP78 mRNA expression was observed in three of the four cell lines (mean, 1.96-fold reduction; P = 0.001) (Figure 2B). The decrease in BiP/GRP78 expression was an early event after R-CHOP administration and was evident after 8 hours of treatment in the absence of any cytotoxicity (data not shown). Accordingly, a 15% to 40% reduction of BiP/GRP78 protein levels was observed in cells treated with R-CHOP (Figure 2C), although there was no statistical correlation between mRNA and protein levels.

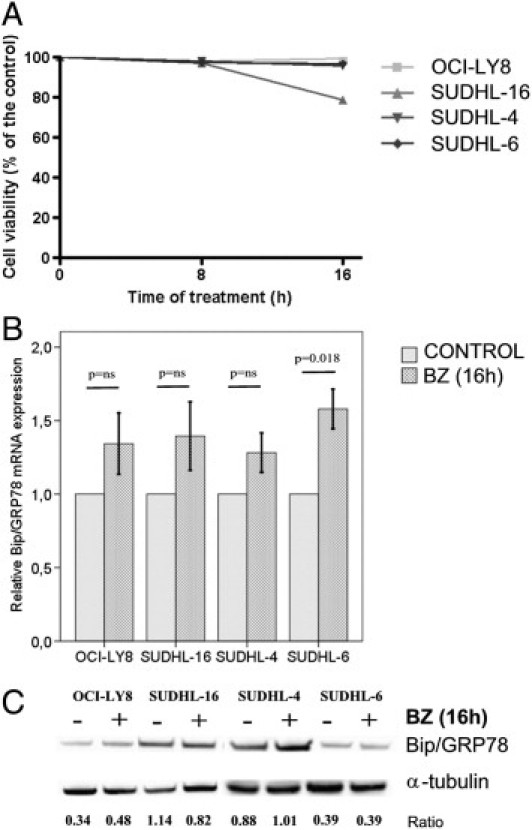

R-CHOP Treatment Overcomes DLBCL Resistance to Bortezomib by Decreasing the Expression of BiP/GRP78

DLBCL cell lines are resistant to bortezomib monotherapy, whereas in only a subset of them proteasome inhibition induces apoptosis.29, 30, 44 To explore the possible role of BiP/GRP78 in this primary resistance, we exposed DLBCL cell lines to a 5 nmol/L dose of bortezomib.29 SUDHL-16 was the single cell line sensitive to bortezomib, with a cell death rate of 21% after a 16-hour treatment (Figure 3A). Bortezomib did not affect BiP/GRP78 expression in three of the four cell lines, whereas a transcriptional increase was observed in the bortezomib-resistant SUDHL-6 cell line (P = 0.018) (Figure 3B). Densitometric quantification of the BiP/α-tubulin ratio showed an accumulation of BiP/GRP78 protein at 16 hours of exposure to bortezomib in the bortezomib-resistant OCI-LY8 (41%) and SUDHL-4 (15%) cell lines, whereas in the bortezomib-sensitive SUDHL-16 cell line a 30% reduction of protein levels was observed (Figure 3C). Altogether, these results suggest that a posttranscriptional stabilization of BiP/GRP78 protein may be involved in DLBCL resistance to bortezomib monotherapy.

Figure 3.

Cell survival and BiP/GRP78 gene expression after 16 hours of bortezomib treatment. A: Virtually all cell lines are primary resistant to bortezomib, and only SUDHL-16 cells decrease cell viability up to 25%. B: BiP/GRP78 mRNA expression tends to increase after bortezomib in all cell lines but only reaches statistically significance in SUDHL-6. C: A mild protein induction of BiP/GRP78 was observed only in OCI-LY8 and SUDHL-4 by Western blot, although the differences did not reach statistical significance. Numbers represent the ratio of BiP/GRP78 and α-tubulin optical density. Error bars represent 2 SDs.

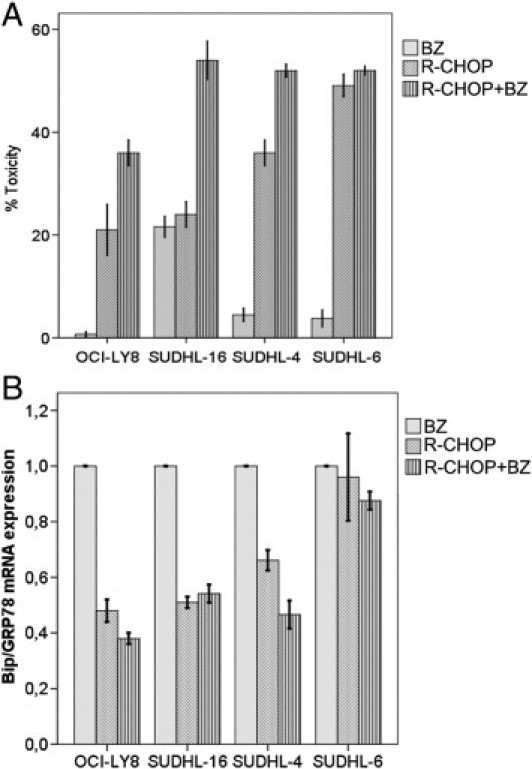

Because R-CHOP treatment leads to BiP/GRP78 protein depletion in DLBCL cells, we then explored whether R-CHOP-BZ may have a beneficial effect. We observed that R-CHOP-BZ substantially increased cell death in three of four cell lines in a magnitude superior to a merely additive effect (Figure 4A). Accordingly, R-CHOP-BZ was able to decrease BiP/GRP78 mRNA expression, thereby reaching substantial higher cytotoxicity (Figure 4B). The benefit of R-CHOP-BZ was mostly observed in the DLBCL cell lines with the highest BiP/GRP78 basal expression levels: SUDHL-4 and SUDHL-16 cells (r2 = 0.88; P = 0.103; data not shown and Figure 3C).

Figure 4.

Cell survival and BiP/GRP78 gene expression after R-CHOP-BZ combination. A: R-CHOP-BZ overcomes primary resistance to bortezomib in all DLBCL cell lines and increased cell death associated with R-CHOP in all cell lines but in SUDHL-6. B: R-CHOP and R-CHOP-BZ significantly reduced BiP/GRP78 mRNA expression in all cell lines. Error bars represent 2 SDs.

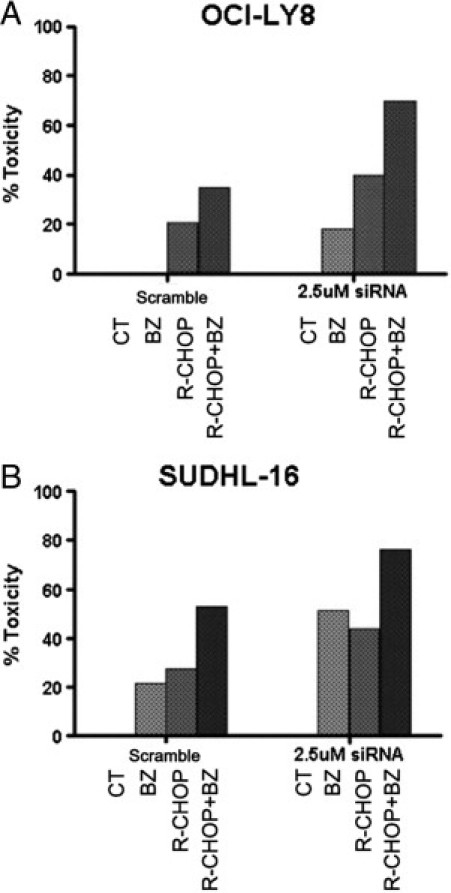

Selective BiP/GRP78 Silencing Sensitizes DLBCL Cell Lines to Bortezomib Mimicking the R-CHOP Effect

To confirm the role of BiP/GRP78 as an antiapoptotic molecule in DLBCL, we explored the effect of the inhibition of BiP/GRP78 in the bortezomib- and R-CHOP–induced cytotoxicity with an siRNA strategy to selectively down-regulate BiP/GRP78 expression. OCI-LY8 and SUDHL16 were selected for this assay because of their similar responses to R-CHOP, whereas they represented the cell lines most resistant and sensitive to bortezomib, respectively. As expected, the siRNA inhibition of BiP/GRP78 was dose dependent (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). BiP/GRP78 knockdown (2.5 μmol/L) rendered both cell lines sensitive to the proteasome inhibition (Figure 5). In fact, in the primary bortezomib-resistant cell line OCI-LY8, BiP/GRP78 silencing led to 18% of the cell death rate after bortezomib compared with 1% observed with the scramble siRNA (Figure 5A). Similarly, bortezomib-mediated apoptosis also increased in SUDHL16 cells from 12% observed in nontargeting siRNA transfected cells to 52% after silencing of BiP/GRP78 (Figure 5B). Moreover, the siRNA inhibition of BiP/GRP78 also sensitized cells to R-CHOP alone, with an overall increase of cell death close to 25% in both cell lines (Figure 5). R-CHOP-BZ mimicked the effect of the siRNA with similar effects on cell toxicity (R-CHOP-BZ versus siRNA and bortezomib: 50% versus 52% in SUDHL16 and 35% versus 18% in OCI-Ly8).

Figure 5.

Selective BiP/GRP78 inhibition sensitizes DLBCL cell lines to bortezomib, mimicking the effect of R-CHOP in the most bortezomib-resistant (OCI-LY8) (A) and the most bortezomib-sensitive (SUDHL-16) (B) cell lines.

Discussion

The activation of the ER stress response, also known as unfolded protein response, is a feature of aggressive tumors, including B-cell lymphomas.17 In DLBCL patients, we have previously shown that Xbp1 activation, the major effector of the unfolded protein response, is associated with poor overall survival.17

We characterize the expression of BiP/GRP78, a molecular chaperone key for the ER homeostasis and the unfolded protein response activation, in DLBCL. We demonstrate that high BiP/GRP78 expression is associated with poor overall survival in DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP regardless of the germinal or postgerminal center derivation. Moreover, we also show that treatment with R-CHOP reduces BiP/GRP78 expression in three of four DLBCL cell lines studied. Interestingly, the cell line expressing the highest basal levels of BiP/GRP78 (SUDHL-16, data not shown) has the lowest response to R-CHOP. Conversely, the cell line showing the lowest BiP/GRP78 expression (SUDHL-6, data not shown) displays the highest R-CHOP cytotoxicity. These findings suggest that basal BiP/GRP78 expression may have a role in the prediction of the responses to the standard treatment. This is in agreement with prior in vitro models of bladder and breast cancers, showing that BiP/GRP78 expression confers resistance to doxorubicin.31, 45

Doxorubicin-based regimens are the current standard therapy for DLBCL, but there is still a substantial number of patients for whom standard treatment is insufficiently effective or has major toxic effects.2, 3, 46 Moreover, high-risk patients have still unfavorable outcomes.46 Since the addition of rituximab to polychemotherapy, no other treatments have shown greater benefit in these patients, although some clinical and preclinical trials have shown the efficacy of new combinations of drugs, including proteasome inhibitors.6, 7, 30, 43

Bortezomib-mediated proteasome inhibition profoundly affects the ER homeostasis and induces an ER stress response that leads to cell death, potentially overcoming the intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy.44 The use of bortezomib, both as a single agent or in combination with a wide range of agents, is currently under investigation to improve survival in aggressive lymphomas.6, 9, 14, 47 Although bortezomib monotherapy is mainly ineffective in DLBCL cell lines,29 the combination with immunochemotherapy has been shown to benefit a selected group of patients with relapsed or refractory ABC DLBCL7 and in previously untreated patients with advance disease.6 We have demonstrated that almost all of the DLBCL cell lines studied were primary resistant to bortezomib monotherapy. Moreover, we have demonstrated that after bortezomib treatment BiP/GRP78 is induced in the bortezomib-resistant cell lines OCI-LY8 and SUDHL-4, as well as in multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma.12, 48

The selective inhibition of BiP/GRP78 by siRNA significantly overcomes the constitutive resistance to bortezomib and enhances cell toxicity in response to proteasome inhibition, suggesting an important role for BiP/GRP78 in the mechanisms of response to bortezomib. Moreover, some treatments, such as vomitoxin and epigallocatechin gallate, may reduce BiP/GRP78 transcription49 and can be used to increase bortezomib cytotoxicity. The addition of R-CHOP reduces BiP/GRP78 expression and overcomes its bortezomib-mediated induction, which is not a mere consequence of cell death because this transcriptional repression was evident in early time points even before any cytotoxicity effect could be observed.

More importantly, R-CHOP-BZ (low dose) results in higher cytotoxicity in all cell lines. Notably, DLBCL cell lines with high basal expression tend to have a better response to the combined R-CHOP-BZ therapy. Proteasome inhibition through bortezomib is an indirect way to inhibit the transcription factor NF-κB, blocking the degradation of its inhibitor IκBα. The DLBCL ABC subtype is dependent on the constitutive activity of this pathway to survive, and the inhibition of NF-κB kills ABC but not GCB cells.50 Likewise, the response rate to bortezomib in clinical trials was higher in patients with the ABC subtype than in those with the GCB subtype (83% versus 13%).7 Interestingly, all cell lines studied here were DLBCL GCB subtype carrying the t(14;18)(q32;q21), and all of them had increased cytotoxicity after R-CHOP-BZ. This finding suggests that patients with non-ABC type DLBCL may benefit from bortezomib-containing regimens. Recently, R-CHOP-BZ resulted in 86% of complete responses with no differences in terms of overall survival or progression-free survivals between GCB and ABC subtypes.6 Preliminary clinical results suggest that bortezomib may have antitumor effects also in the GCB subtype.6, 9, 10 The inhibition of proteasome may have sensitized the DLBCL cells to the cytotoxic action of the chemotherapy. Otherwise, bortezomib exhibits NF-κB–independent cytotoxicity in a wide range of different tumor types48, 51, 52, 53 and affects many additional pathways that may be differently used by ABC and GCB subtypes.54

For the first time in the literature we describe the prognostic impact of BiP/GRP78 expression in a homogenous series of DLBCL, all treated with R-CHOP, with a mean follow-up of 2.9 years. Patients with high levels of BiP/GRP78 mRNA have a worse prognosis. This finding is in agreement with previous reports in the literature indicating that BiP/GRP78 has a major role in cancer progression by protecting neoplastic cells from apoptosis and inducing resistance to therapeutic agents.31, 32, 45

We have demonstrated that R-CHOP decreases BiP/GRP78 expression, similarly to the effect of siRNA silencing, sensitizing DLBCL cell lines to bortezomib. Moreover, DLBCL cell lines with high basal expression tend to have a better response to R-CHOP-BZ. Therefore, the analysis of BiP/GRP78 transcripts in DLBCL might allow identifying patients who may benefit from this combination. Moreover, this study provides preclinical evidence that the DLBCL GCB subtype is sensitive to bortezomib; therefore, we propose to expand clinical trials to include all subtypes of DLBCL. In conclusion, our results indicate that decreased BiP/GRP78 expression is a requisite to sensitizing DLBCL cells to bortezomib and that this can be achieved with R-CHOP-BZ, offering a rationale for a new combination therapy to improve survival in these patients.

Footnotes

Supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, grants PI080095 (A.M.) and PI09/00060 (G.R.), the Spanish Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología grant SAF08-3630 (E.C.), and Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa del Cáncer grants RD06/0020/0039 (E.C.) and RD06/0020/0014 (D.C.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.031.

Supplementary Data

siRNA silencing efficiency in OCI-LY8 and SUDHL-16. The upper panel shows the siRNA efficiency that ranges from 69.7% (0.5nM of siRNA) to 79.6% (2.5 nM) in OCI-LY8 and from 81.2% (0.5 nmol/L) to 99.3% (2.5 nmol/L) in SUDHL16. The lower panel shows the subsequent BiP/GRP78 protein expression using Western blot.

References

- 1.Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Pileri S., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2008. WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coiffier B., Lepage E., Briere J., Herbrecht R., Tilly H., Bouabdallah R., Morel P., Van Den N.E., Salles G., Gaulard P., Reyes F., Lederlin P., Gisselbrecht C. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumontet C., Mounier N., Munck J.N., Bosly A., Morschauser F., Simon D., Marit G., Casasnovas O., Reman O., Molina T., Reyes F., Coiffier B. Factors predictive of early death in patients receiving high-dose CHOP (ACVB regimen) for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a GELA study. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:210–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feugier P., Van H.A., Sebban C., Solal-Celigny P., Bouabdallah R., Ferme C., Christian B., Lepage E., Tilly H., Morschhauser F., Gaulard P., Salles G., Bosly A., Gisselbrecht C., Reyes F., Coiffier B. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4117–4126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonard J.P., Martin P., Barrientos J., Elstrom R. Targeted treatment and new agents in diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2008;45:S11–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruan J., Martin P., Furman R.R., Lee S.M., Cheung K., Vose J.M., Lacasce A., Morrison J., Elstrom R., Ely S., Chadburn A., Cesarman E., Coleman M., Leonard J.P. Bortezomib plus CHOP-rituximab for previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:690–697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunleavy K., Pittaluga S., Czuczman M.S., Dave S.S., Wright G., Grant N., Shovlin M., Jaffe E.S., Janik J.E., Staudt L.M., Wilson W.H. Differential efficacy of bortezomib plus chemotherapy within molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2009;113:6069–6076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furman R.R., Martin P., Ruan J., Cheung Y.K., Vose J.M., LaCasce A.S., Elstrom R., Coleman M., Leonard J.P. Phase 1 trial of bortezomib plus R-CHOP in previously untreated patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2010;116:5432–5439. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barr P.M., Fu P., Lazarus H.M., Horvath N., Gerson S.L., Koc O.N., Bahlis N.J., Snell M.R., Dowlati A., Cooper B.W. Phase I trial of fludarabine, bortezomib and rituximab for relapsed and refractory indolent and mantle cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2009;147:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedberg J.W., Vose J.M., Kelly J.L., Young F., Bernstein S.H., Peterson D., Rich L., Blumel S., Proia N.K., Liesveld J., Fisher R.I., Armitage J.O., Grant S., Leonard J.P. The combination of bendamustine, bortezomib, and rituximab for patients with relapsed/refractory indolent and mantle cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:2807–2812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-314708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong H., Chen L., Chen X., Gu H., Gao G., Gao Y., Dong B. Dysregulation of unfolded protein response partially underlies proapoptotic activity of bortezomib in multiple myeloma cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:974–984. doi: 10.1080/10428190902895780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obeng E.A., Carlson L.M., Gutman D.M., Harrington W.J., Jr., Lee K.P., Boise L.H. Proteasome inhibitors induce a terminal unfolded protein response in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107:4907–4916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher R.I., Bernstein S.H., Kahl B.S., Djulbegovic B., Robertson M.J., de V.S., Epner E., Krishnan A., Leonard J.P., Lonial S., Stadtmauer E.A., O'Connor O.A., Shi H., Boral A.L., Goy A. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4867–4874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goy A., Bernstein S.H., Kahl B.S., Djulbegovic B., Robertson M.J., de V.S., Epner E., Krishnan A., Leonard J.P., Lonial S., Nasta S., O'Connor O.A., Shi H., Boral A.L., Fisher R.I. Bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: updated time-to-event analyses of the multicenter phase 2 PINNACLE study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:520–525. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagannath S., Barlogie B., Berenson J.R., Siegel D.S., Irwin D., Richardson P.G., Niesvizky R., Alexanian R., Limentani S.A., Alsina M., Esseltine D.L., Anderson K.C. Updated survival analyses after prolonged follow-up of the phase 2, multicenter CREST study of bortezomib in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:537–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M., Zhou Y., Zhang L., Nguyen C.A., Romaguera J. Use of bortezomib in B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:983–991. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.7.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balague O., Mozos A., Martinez D., Hernandez L., Colomo L., Mate J.L., Teruya-Feldstein J., Lin O., Campo E., Lopez-Guillermo A., Martinez A. Activation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated transcription factor x box-binding protein-1 occurs in a subset of normal germinal-center B cells and in aggressive B-cell lymphomas with prognostic implications. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2337–2346. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee E., Nichols P., Spicer D., Groshen S., Yu M.C., Lee A.S. GRP78 as a novel predictor of responsiveness to chemotherapy in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7849–7853. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pyrko P., Schonthal A.H., Hofman F.M., Chen T.C., Lee A.S. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP as a novel target for increasing chemosensitivity in malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9809–9816. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J., Yin Y., Hua H., Li M., Luo T., Xu L., Wang R., Liu D., Zhang Y., Jiang Y. Blockade of GRP78 sensitizes breast cancer cells to microtubules-interfering agents that induce the unfolded protein response. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:3888–3897. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y., Wang W., Wang S., Wang J., Shao S., Wang Q. Down-regulation of GRP78 is associated with the sensitivity of chemotherapy to VP-16 in small cell lung cancer NCI-H446 cells. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:372. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong D., Ni M., Li J., Xiong S., Ye W., Virrey J.J., Mao C., Ye R., Wang M., Pen L., Dubeau L., Groshen S., Hofman F.M., Lee A.S. Critical role of the stress chaperone GRP78/BiP in tumor proliferation, survival, and tumor angiogenesis in transgene-induced mammary tumor development. Cancer Res. 2008;68:498–505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H.Q., Du Z.X., Zhang H.Y., Gao D.X. Different induction of GRP78 and CHOP as a predictor of sensitivity to proteasome inhibitors in thyroid cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3258–3270. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J., Jiang Y., Jia Z., Li Q., Gong W., Wang L., Wei D., Yao J., Fang S., Xie K. Association of elevated GRP78 expression with increased lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2006;23:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Y., Hendershot L.M. The role of the unfolded protein response in tumour development: friend or foe? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:966–977. doi: 10.1038/nrc1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J., Lee A.S. Stress induction of GRP78/BiP and its role in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:45–54. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J., Ni M., Lee B., Barron E., Hinton D.R., Lee A.S. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP is required for endoplasmic reticulum integrity and stress-induced autophagy in mammalian cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1460–1471. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jamora C., Dennert G., Lee A.S. Inhibition of tumor progression by suppression of stress protein GRP78/BiP induction in fibrosarcoma B/C10ME. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7690–7694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shringarpure R., Catley L., Bhole D., Burger R., Podar K., Tai Y.T., Kessler B., Galardy P., Ploegh H., Tassone P., Hideshima T., Mitsiades C., Munshi N.C., Chauhan D., Anderson K.C. Gene expression analysis of B-lymphoma cells resistant and sensitive to bortezomib. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:145–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dasmahapatra G., Lembersky D., Rahmani M., Kramer L., Friedberg J., Fisher R.I., Dent P., Grant S. Bcl-2 antagonists interact synergistically with bortezomib in DLBCL cells in association with JNK activation and induction of ER stress. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:808–819. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.9.8131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 31.Reddy R.K., Mao C., Baumeister P., Austin R.C., Kaufman R.J., Lee A.S. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein GRP78 protects cells from apoptosis induced by topoisomerase inhibitors: role of ATP binding site in suppression of caspase-7 activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20915–20924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ranganathan A.C., Zhang L., Adam A.P., Guirre-Ghiso J.A. Functional coupling of p38-induced up-regulation of BiP and activation of RNA-dependent protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase to drug resistance of dormant carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1702–1711. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheson B.D., Horning S.J., Coiffier B., Shipp M.A., Fisher R.I., Connors J.M., Lister T.A., Vose J., Grillo-Lopez A., Hagenbeek A., Cabanillas F., Klippensten D., Hiddemann W., Castellino R., Harris N.L., Armitage J.O., Carter W., Hoppe R., Canellos G.P. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez A., Aymerich M., Castillo M., Colomer D., Bellosillo B., Campo E., Villamor N. Routine use of immunophenotype by flow cytometry in tissues with suspected hematological malignancies. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2003;56:8–15. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.10044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenz G., Wright G., Dave S.S., Xiao W., Powell J., Zhao H., Xu W., Tan B., Goldschmidt N., Iqbal J., Vose J., Bast M., Fu K., Weisenburger D.D., Greiner T.C., Armitage J.O., Kyle A., May L., Gascoyne R.D., Connors J.M., Troen G., Holte H., Kvaloy S., Dierickx D., Verhoef G., Delabie J., Smeland E.B., Jares P., Martinez A., Lopez-Guillermo A., Montserrat E., Campo E., Braziel R.M., Miller T.P., Rimsza L.M., Cook J.R., Pohlman B., Sweetenham J., Tubbs R.R., Fisher R.I., Hartmann E., Rosenwald A., Ott G., Muller-Hermelink H.K., Wrench D., Lister T.A., Jaffe E.S., Wilson W.H., Chan W.C., Staudt L.M. Stromal gene signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2313–2323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roue G., Perez-Galan P., Lopez-Guerra M., Villamor N., Campo E., Colomer D. Selective inhibition of IkappaB kinase sensitizes mantle cell lymphoma B cells to TRAIL by decreasing cellular FLIP level. J Immunol. 2007;178:1923–1930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hothorn T., Lausen B. On the exact distribution of maximally selected rank statistics. Computational Stat Data Anal. 2003;43:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan E.L., Meier P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ni M., Zhou H., Wey S., Baumeister P., Lee A.S. Regulation of PERK signaling and leukemic cell survival by a novel cytosolic isoform of the UPR regulator GRP78/BiP. PLoS One. 2009;4:36868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shani G., Fischer W.H., Justice N.J., Kelber J.A., Vale W., Gray P.C. GRP78 and Cripto form a complex at the cell surface and collaborate to inhibit transforming growth factor Î2 signaling and enhance cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:666–677. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01716-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun F.C., Wei S., Li C.W., Chang Y.S., Chao C.C., Lai Y.K. Localization of GRP78 to mitochondria under the unfolded protein response. Biochem J. 2006;396:31–39. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohammad R.M., Wall N.R., Dutcher J.A., Al-Katib A.M. The addition of bryostatin 1 to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) chemotherapy improves response in a CHOP-resistant human diffuse large cell lymphoma xenograft model. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4950–4956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohammad R.M., Al-Katib A., Aboukameel A., Doerge D.R., Sarkar F., Kucuk O. Genistein sensitizes diffuse large cell lymphoma to CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1361–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strauss S.J., Higginbottom K., Juliger S., Maharaj L., Allen P., Schenkein D., Lister T.A., Joel S.P. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib acts independently of p53 and induces cell death via apoptosis and mitotic catastrophe in B-cell lymphoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2783–2790. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong D., Ko B., Baumeister P., Swenson S., Costa F., Markland F., Stiles C., Patterson J.B., Bates S.E., Lee A.S. Vascular targeting and antiangiogenesis agents induce drug resistance effector GRP78 within the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5785–5791. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coiffier B., Thieblemont C., Van Den N.E., Lepeu G., Plantier I., Castaigne S., Lefort S., Marit G., Macro M., Sebban C., Belhadj K., Bordessoule D., Ferme C., Tilly H. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040–2045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leonard J.P., Furman R.R., Coleman M. Proteasome inhibition with bortezomib: a new therapeutic strategy for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:971–979. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roue G., Perez-Galan P., Mozos A., Lopez-Guerra M., Xargay-Torrent S., Rosich L., Saborit-Villarroya I., Normant E., Campo E., Colomer D. The Hsp90 inhibitor IPI-504 overcomes bortezomib resistance in mantle cell lymphoma in vitro and in vivo by down-regulation of the prosurvival ER chaperone BiP/Grp78. Blood. 2011;117:1270–1279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang G.H., Li S., Pestka J.J. Down-regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone GRP78/BiP by vomitoxin (Deoxynivalenol) Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;162:207–217. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis R.E., Brown K.D., Siebenlist U., Staudt L.M. Constitutive nuclear factor kappaB activity is required for survival of activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1861–1874. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perez-Galan P., Roue G., Villamor N., Montserrat E., Campo E., Colomer D. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib induces apoptosis in mantle-cell lymphoma through generation of ROS and Noxa activation independent of p53 status. Blood. 2006;107:257–264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rizzatti E.G., Mora-Jensen H., Weniger M.A., Gibellini F., Lee E., Daibata M., Lai R., Wiestner A. Noxa mediates bortezomib induced apoptosis in both sensitive and intrinsically resistant mantle cell lymphoma cells and this effect is independent of constitutive activity of the AKT and NF-kappaB pathways. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:798–808. doi: 10.1080/10428190801910912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang D.T., Young K.H., Kahl B.S., Markovina S., Miyamoto S. Prevalence of bortezomib-resistant constitutive NF-kappaB activity in mantle cell lymphoma. Mol Cancer. 2008;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lenz G., Staudt L.M. Aggressive Lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1417–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0807082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

siRNA silencing efficiency in OCI-LY8 and SUDHL-16. The upper panel shows the siRNA efficiency that ranges from 69.7% (0.5nM of siRNA) to 79.6% (2.5 nM) in OCI-LY8 and from 81.2% (0.5 nmol/L) to 99.3% (2.5 nmol/L) in SUDHL16. The lower panel shows the subsequent BiP/GRP78 protein expression using Western blot.