Abstract

In animals, circadian oscillators are based on a transcription-translation circuit that revolves around the transcription factors CLOCK and BMAL1. We found that the JumonjiC (JmjC) and ARID domain-containing histone lysine demethylase 1a (JARID1a) formed a complex with CLOCK-BMAL1, which was recruited to the Per2 promoter. JARID1a increased histone acetylation by inhibiting histone deacetylase 1 function and enhanced transcription by CLOCK-BMAL1 in a demethylase-independent manner. Depletion of JARID1a in mammalian cells reduced Per promoter histone acetylation, dampened expression of canonical circadian genes, and shortened the period of circadian rhythms. Drosophila lines with reduced expression of the Jarid1a homolog, lid, had lowered Per expression and similarly altered circadian rhythms. JARID1a thus has a nonredundant role in circadian oscillator function.

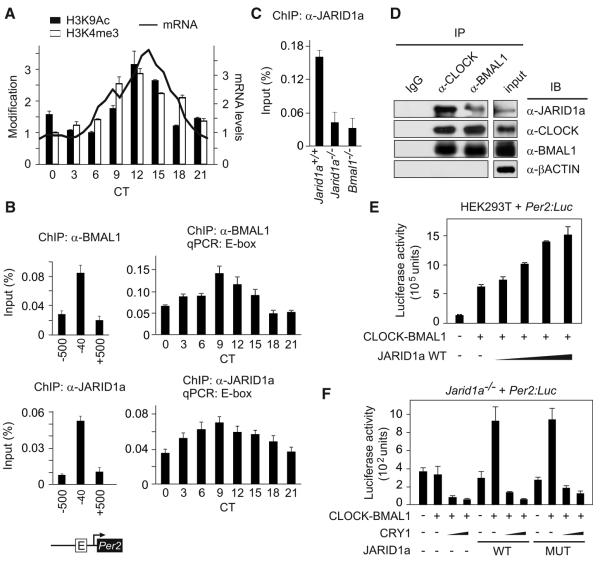

To gain insight into the dynamics of chromatin modifications and the function of CLOCK-BMAL1 transcription factors in the circadian clock, we measured the state of two histone modifications that correlate with active transcription, acetylation of histone 3 (H3) lysine 9 (H3K9Ac), and trimethylation of H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) at the Per2 promoter (1). In mouse liver, both modifications synchronously oscillated at the Per2 gene promoter CLOCK-BMAL1 E2-binding site (“E-box”) (2), with lowest amounts at circadian time (CT, the endogenous, free-running time) 3 hours after the onset of activity (CT3) and peak amounts at CT12 (Fig. 1A). The peaks of histone modification were followed by those of Per2 mRNA abundance. We also found BMAL1 abundance rhythms at the E-box, which reached a maximum at CT9 (Fig. 1B). Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) generate rhythms in histone acetylation and have important roles in circadian rhythms (3, 4). H3K4me3 modification at promoter regions correlates with transcriptional potential, which suggests that this mark helps maintain a transcriptionally poised state (5). Recently, the H3K4 methyltransferase MLL1 was shown to have a necessary role in CLOCK-BMAL1-dependent transcription (6).

Fig. 1.

JARID1a coactivates CLOCK-BMAL1-mediated transcription of Per genes. (A) H3K4 trimethylation and H3K9 acetylation oscillations at the Per2 promoter E-box in mouse liver shown alongside Per2 mRNA expression (secondary y axis). Normalized average (+SEM, n = 3) of chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) performed with antibodies against H3K4me3 or H3K9Ac followed by QPCR analysis. Chromatin modifications shown as a percentage of total chromatin used (input) normalized to the corresponding lowest value (H3K4me3 = 0.27%, H3K9Ac = 0.25%) for ease of comparison. (B) Abundance of BMAL1 and JARID1a in mouse liver at the Per2 promoter E-box and flanking regions. (C) Absence of JARID1a from the Per2 promoter E-box in Bmal1−/− cells. (D) Association of endogenous JARID1a and CLOCK-BMAL1. Immunoprecipitates (IPs) obtained with the indicated antibodies from asynchronous U2OS (a human osteosarcoma cell line) nuclear extracts were immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies against JARID1a, CLOCK, BMAL1, or βACTIN. (E) Effect of JARID1a on CLOCK-BMAL1-dependent transcription from a Per2:Luc reporter. Luciferase activity (light counts) from HEK293T cells transiently expressing full-length JARID1a cDNA and Per2:Luc reporter construct are shown. (F) Wild-type (WT) or demethylase-mutant JARID1a H483A (MUT) rescues CLOCK-BMAL1 activation of a Per2 reporter construct in Jarid1a−/− cells.

We focused on a JumonjiC (JmjC) domain-containing H3K4me3 demethylase family with four mammalian and one insect gene members (fig. S1). In murine liver chromatin, JARID1a was enriched at the Per2 E-box, and its profile at this site coincided with that of BMAL1 (Fig. 1B). Jarid1a expression in liver did not show robust oscillations (fig. S2), which suggested that recruitment of JARID1a to the Per2 promoter might be mediated by the circadian machinery. Indeed, JARID1a recruitment to the Per2 promoter E-box but not at a non-CLOCK-BMAL1 JARID1a target is reduced in Bmal1−/− cells (Fig. 1C and fig. S17A). Consistently, immunoprecipitation of endogenous CLOCK or BMAL1 from nuclear extracts copurified with endogenous JARID1a (Fig. 1D). Similarly, CLOCK and BMAL1 associated with immunoprecipitated JARID1a (fig. S3). Overexpression of JARID1a enhanced CLOCK-BMAL1-mediated transcription from Per2 (Fig. 1E) and Per1 (fig. S4A) promoters in a dose-dependent manner but failed to coactivate expression from an unrelated (E74-Luc) reporter (fig. S4D). Furthermore, coactivation of CLOCK-BMAL1 by JARID1a did not require its histone demethylase activity, as JARID1a mutants that carry a loss-of-function mutation (H483A, in which Ala replaces His483) (7) or that lack the JmjC domain enhanced CLOCK-BMAL1 activity, reversedHDAC1 repression, and increased acetylation amounts at the Per2 E-box (Fig. 1F and figs. S4B, S4C, and S5).

In contrast, JARID1b and JARID1c repressed CLOCK-BMAL1-mediated activation of Per2 transcription (fig. S6, A and B). Accordingly, overexpression of JARID1b and JARID1c, but not JARID1a, reduced H3K4me3 modification at the Per2 promoter (fig. S6C). Overall, these results suggest that JARID1a enhances CLOCK-BMAL1 activation of the Per2 promoter, where- as JARID1b and JARID1c might function to reverse its H3K4me3 levels during the repression phase of Per transcription.

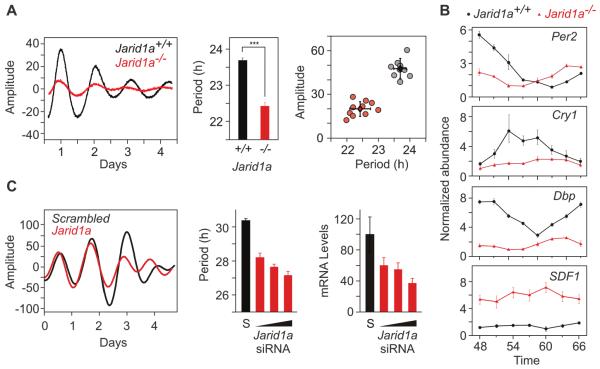

To test whether JARID1a has a nonredundant role in the cell-autonomous oscillator, we stably transfected a Per2:Luciferase (Per2:Luc) reporter into fibroblasts derived from either Jarid1a+/+ (wild type; WT) or Jarid1a−/− (knockout, KO) mice (7) and monitored circadian rhythms in Per2:Luc luminescence. In cell populations (Fig. 2A and fig. S7A) and single cells (fig. S8), Per2 transcriptional rhythms in a Jarid1a−/− genetic background showed a significantly shorter period than those of WT controls [WT = 23.7 ± 0.2 hours, KO = 22.4 ± 0.3 hours, P = 6.68 × 10-8, n = 10 each genotype, one-way analysis of variance(ANOVA)] (Fig. 2A). Amounts of endogenous Per2 transcript were also reduced and oscillated with a shorter period in Jarid1a−/− cells (Fig. 2B). Similarly, other CLOCK-BMAL1 targets were significantly reduced in Jarid1a−/− cells, and their rhythms were either absent or dampened (Fig. 2B and fig. S9). In contrast, abundance of SDF1 mRNA, a repressive target of the histone demethylase (KDM) activity of JARID1a (7), was increased in Jarid1a−/− fibroblasts. Acute small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated depletion of Jarid1a mRNA also shortened circadian period length in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C and fig. S7B). Conversely, transient transfection reconstitution of either wild-type or demethylase mutant JARID1a into Jarid1a−/− cells resulted in a circadian period lengthening (fig. S10). These results indicate that JARID1a has a nonredundant role in maintaining the normal periodicity of the circadian oscillator.

Fig. 2.

JARID1a is required for normal circadian function. (A) Real-time bioluminescence from Jarid1a+/+ (black) and Jarid1a−/− (red) mouse fibroblasts stably expressing a Per2:Luc construct. (Middle and right) Average period lengths (+SEM, n = 10) and amplitude estimates (***P < 0.001, two-tailed Student’s t test). (B) Per2, Cry1, Dbp, and SDF1 mRNA abundance in Jarid1a+/+cells (black) and Jarid1a−/− cells (red). Forty-eight hours after circadian synchronization, cells were collected at 3-hour intervals over the course of 24 hours, and the mRNA abundance was analyzed by reverse transcription (RT)-QPCR and normalized to that of Gapdh. Average normalized values (±SEM, n = 3) are plotted at various times after cell synchronization. (C) Representative real-time luminescence from U2OS cells stably expressing Bmal1:Luc and transfected with scrambled (S, black) or Jarid1a siRNA (red). Effects of different Jarid1a siRNA concentrations (10, 20, and 40 nM) on the endogenous Jarid1a mRNA abundance (average + SEM, n = 3) and period length (average + SEM, n = 5) relative to those of cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (40 nM). Representative results from at least three independent repetitions are shown.

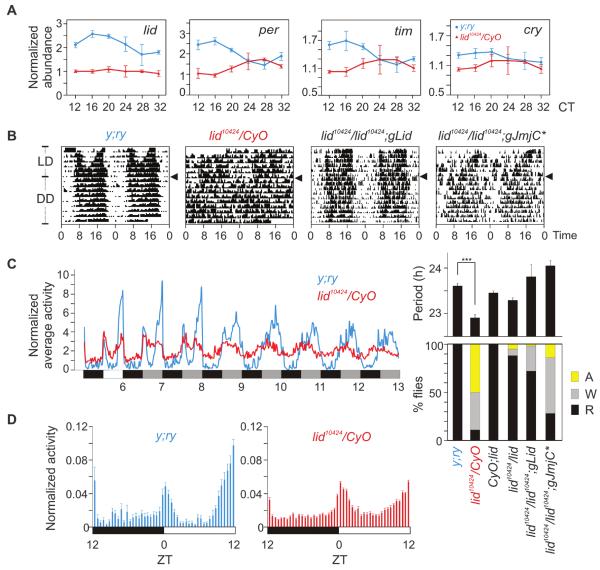

The overall mechanism and several components of the circadian oscillator are conserved between mammals and insects. The Drosophila genome has only one Jarid1 family gene, little imaginal discs (lid) (fig. S1). Flies carrying the hypomorphic allele lid10424 (P-element insertion in the first intron) over the balancer chromosome CyO (lid10424/CyO) expressed less lid mRNA than did WT y;ry flies (Fig. 3A). Consistent with our observations in Jarid1a−/− fibroblasts (Figs. 1 and 2), lid10424/CyO flies also expressed reduced amounts of per, cry, and timeless (tim) mRNA. These lid10424/CyO flies showed normal activity distribution under a 12 hours of light:12 hours of dark (LD) cycle (Fig. 3B), and their total activity (1030 ± 44, average beam breaks for 3 days in LD, SEM, n = 75) was equivalent (P > 0.13, oneway ANOVA) to that of WT y;ry (831 ± 85, SEM, n = 16) or +/CyO (938 ± 60 SEM, n = 45) flies, which implied no deficit in locomotion or light:dark entrainment of the circadian clock.

Fig. 3.

Circadian rhythm disruption in lid10424 flies. (A) RT-QPCR of lid, per, cry, and tim mRNA in the heads of y;ry (black) and lid10424/CyO (red) flies collected every 4 hours after 72 hours in constant darkness (±SEM, n = 3). (B) Representative circadian double-plotted actograms of wild-type lid+/+ (y;ry), lid10424/CyO, lid10424/lid10424;gLid, and lid10424/lid10424;gJmjC* flies under LD or DD conditions. Arrowheads indicate transition from LD to DD. (C) (Left) Normalized average activity of y;ry (black) and lid10424/CyO flies (red) (n = 33) under LD and DD conditions. (Right) Summary of the circadianactivity rhythms in various Drosophila strains tested. Histogram shows the percentage of flies with normal (R, rhythmic), weak (W) or nodetectable(A, arrhythmic) circadian activity rhythms (+SEM). (D) Normalized average activity (+SEM; n = 16 to 75) in 30-min bins during the light:dark period show two major phases of activities in y;ry flies at morning and evening.

However, under constant darkness (DD), the lid10424/CyO flies exhibited disrupted circadian activity rhythms. The majority of lid10424/CyO flies showed no or weak circadian activity rhythms (Fig. 3, B and C). Those lid10424/CyO flies with detectable rhythms showed significant period shortening (Fig. 3C) (lid10424/CyO = 22.91 ± 0.04 hours, y;ry = 23.61 ± 0.06 hours; average ± SEM, n = 16 and 75; P < 0.001). Expression of a genomic copy of lid in lid10424/lid10424 homozygous flies (lid10424/lid10424;gLid) restored Lid protein expression to near-WT amounts and also restored circadian activity rhythms (Fig. 3C and fig. S11). Furthermore, a demethylase-deficient Lid allele (8) partially rescued the circadian phenotype (lid10424/lid10424;gJmjC*). Under LD and DD, the lid10424 flies exhibited attenuated day:night differences in activity. Specifically, the lid10424 flies exhibited increased activity during midday and reduced dark anticipation (Fig. 3D). Comparable circadian rhythm disruption and reduced expression of CLOCK-BMAL1 (or CYC) targets in both Drosophila and mammalian cells supports a conserved role of lid/Jarid1 in the insect and mammalian circadian oscillator.

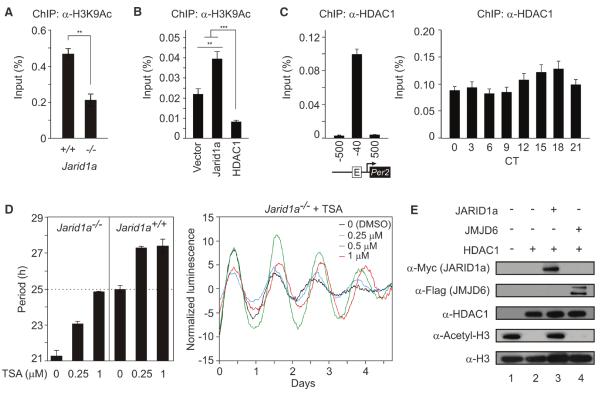

In Jarid1a−/− mouse fibroblasts, the Per2 promoter region showed an increased abundance of H3K4me3 (fig. S12A), but a significantly reduced amount of acetylated H3K9 relative to those of WTcontrols (Fig. 4A). Conversely, overexpression of JARID1a in human embryonickidney-293 cells (HEK293T cells) increased accumulation of H3K9Ac at the Per2 promoter (Fig. 4B), but not at a control promoter (fig. S12C). This suggests that coordinated increases in both H3K4me3 and histone acetylation are required for sufficient Per induction. Recruitment of JARID1a to Per promoters might promote H3K9 acetylation levels during Per transcription.

Fig. 4.

Dynamic interaction between HDAC and JARID1a correlates with normal histone acetylation at Per promoter. (A) H3K9Ac detected by ChIP-QPCR in Jarid1a−/− or WT cells (average +SEM, n = 3; **P < 0.05). (B) H3K9 acetylation at the endogenous Per2 promoter after overexpression of JARID1a or HDAC1 (**P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001, n = 3 per group, one-way ANOVA). (C) ChIP-QPCR quantification of HDAC1 at E-box of Per2 promoter in mouse liver. For (A) to (C), chromatin modifications are presented as percent of total chromatin used for immunoprecipitation (% input). (D) Effect of various concentrations of TSA on Per2:Luc in Jarid1a−/− cells. Representative real-time traces are shown. (E) Acetylated histone H3 (lane 1) was incubated with 100 ng HDAC1 (lane 2), along with purified JARID1a (lane 3) or JMJD6 (lane 4), and analyzed by immunoblot.

Lid inhibits histone deacetylase Rpd3 to activate transcription at specific loci (9). Such HDAC inhibition by Lid, which is independent of its KDM activity, is consistent with the observed activation of CLOCK and BMAL1 by JARID1a (Fig. 1F and figs. S4 and S5). JARID1a also coimmunoprecipitated HDAC1 in mammalian cells (fig. S13). Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative PCR (ChIP-QPCR) analysis from mouse liver chromatin showed a nearly constant HDAC1 occupancy at the Per2 E-box (Fig. 4C). Further, its presence at the Per2 promoter was unchanged in Jarid1a−/− cells (fig. S12B). Although HDAC1 likely mediates repression of Per2 transcription (3) (Fig. 4C and fig. S14), its presence during the activation phase is consistent with enrichment of HDACs at promoters of highly expressed and inducible genes (5). The high-amplitude H3K9 acetylation rhythms in the presence of relatively constant amounts of HDAC1 at the Per2 promoter could be partly explained by transient inhibition of HDAC activity. Loss of JARID1a might lead to higher HDAC activity during activation phase, low H3K9 acetylation, and reduced Per transcriptional activation by CLOCK-BMAL1. Indeed, pharmacological inhibition of HDAC by trichostatin A (TSA) led to increased histone acetylation at the Per2 promoter, rescued the period-length defect, and improved the amplitude of Per2:Luc rhythm in Jarid1a−/− cells (Fig. 4D). Similar TSA treatment slightly increased the period length of WT cells, but dampened Per2:Luc oscillations (fig. S15). Affinity-purified JARID1a impaired the ability of HDAC1 to deacetylate acetylated histone H3 in vitro, whereas another JmjC domain-containing protein, JMJD6, could not (Fig. 4E and fig. S16).

These results support a model in whichJARID1a mediates transition from repression to robust activation of Per transcription. During the activation phase, both H3K4me3 and acetylated histones at CLOCK-BMAL1 target sites accumulate in parallel with Per transcription. JARID1a appears to be recruited to the Per promoter in complex with CLOCK-BMAL1, where it inhibits HDAC1 activity to enhance histone acetylation and transcriptional activation. Although purified JARID1a or Lid inhibits HDAC activity in vitro, this mode of regulation is likely gene- and context-dependent in vivo. Jarid1a−/− cells have increased amounts of H3K4me3 at the Per promoter (fig. S12), and overexpression of the JmjC domain of JARID1a slightly repressed Per transcription (fig. S5), which suggest that, in vivo, JARID1a may mediate demethylation or that its presence in the transcriptional complex of target genes is required for proper recruitment of other proteins that carry out this function. However, whereas the lysine demethylase activity of JARID1a is dispensable for normal circadian rhythms in mammalian cells, its HDAC-inhibiting function appears to be necessary for proper oscillator function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Kaelin for JARID1a antibodies, and Jarid1a−/− and Jarid1a+/+ fibroblasts; and R. Janknecht for JARID1b and JARID1c cDNAs. Supported by NIH grants (EY 16807, DK 091618, and S10 RR027450), the Pew Scholars Program, and a Dana Foundation award to S.P.; a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science fellowship to M.H.; NIH grant F32GM082083 to L.D.; and a Blasker Foundation award to C.V.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

References

- 1.Heintzman ND, et al. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:311. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoo SH, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:2608. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naruse Y, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:6278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6278-6287.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doi M, Hirayama J, Sassone-Corsi P. Cell. 2006;125:497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, et al. Cell. 2009;138:1019. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katada S, Sassone-Corsi P. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:1414. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klose RJ, et al. Cell. 2007;128:889. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Greer C, Eisenman RN, Secombe J. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee N, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:1401. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01643-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.