Abstract

Motivational factors such as social goals are important features of developing social adjustment, and thus researchers studying social adjustment need psychometrically sound measures of social goals. A valid measure of social goals for English-speaking youth is lacking. Such a measure would increase understanding of children’s social adjustment and allow for testing developmental models of social goals and interpersonal functioning. Our aim was to revise the Interpersonal Goals Inventory for Children for an English-speaking sample and examine its validity. The revised IGI-C (IGI-CR) fit a circumplex model and performed as expected with most external criterion variables examined. In addition, some differences were observed across males and females, offering insights into gender differences in social goals. Results support the IGI-CR as a sound measure.

Keywords: social goals, interpersonal circumplex, agency, communion, children

A preponderance of research on children’s social adjustment has focused on the role of social competence and skills (e.g., Najaka, Gottfredson, & Wilson, 2001; Rockhill, Stoep, McCauley, & Katon, 2009). Although much of this literature suggests that social skill deficits are associated with poor social adjustment (Lochman & Dodge, 1994; Prinstein & Cillessen, 2003), theories argue that motivational factors such as social goals, in addition to skills, are important in the development of social adjustment. The Social Information Processing model (SIP; Crick & Dodge, 1994) has guided much of the research in this area, and has served to organize individual differences in skills, competencies, and motivations into a useful framework for understanding social behavior. According to the SIP model, skills and competencies alone do not provide an adequate explanation of social behavior, and it is important to consider the value placed on social goals during a social transaction (Rose-Krasnor, 1997). A related literature on social schemas (Salmivalli & Peets, 2009) further suggests that examining perceptions of social context and desired outcomes is important for understanding child and adolescent behavior.

Most of the research examining social goals has focused on youth adjustment and social goals in fairly circumscribed contexts, such as conflict. Though this research and corresponding social goal measures have been useful in understanding how an individual’s desired goals lead to engaging in aggressive behavior, it is less informative for understanding general interpersonal proclivities outside of provocation situations. There is a remarkable dearth of measures assessing children’s general social goals outside of provocation situations, and this has likely limited progress in developing and testing theories of youth social behavior.

Ojanen and colleagues (2005) made a key contribution to the literature by developing the Interpersonal Goals Inventory for Children (IGI-C). This inventory included a comprehensive range of general social goals based on the interpersonal circumplex (IPC) model. However, the IGI-C was written and tested in a Finnish sample of youth, and as of yet this promising measure has not been adapted for the English language. The current study describes the adaptation and revision of the IGI-C for use with English-speaking youth. Like the IGI-C, the revised measure would fill an important gap in the literature by assessing a comprehensive range of social goals based in the IPC.

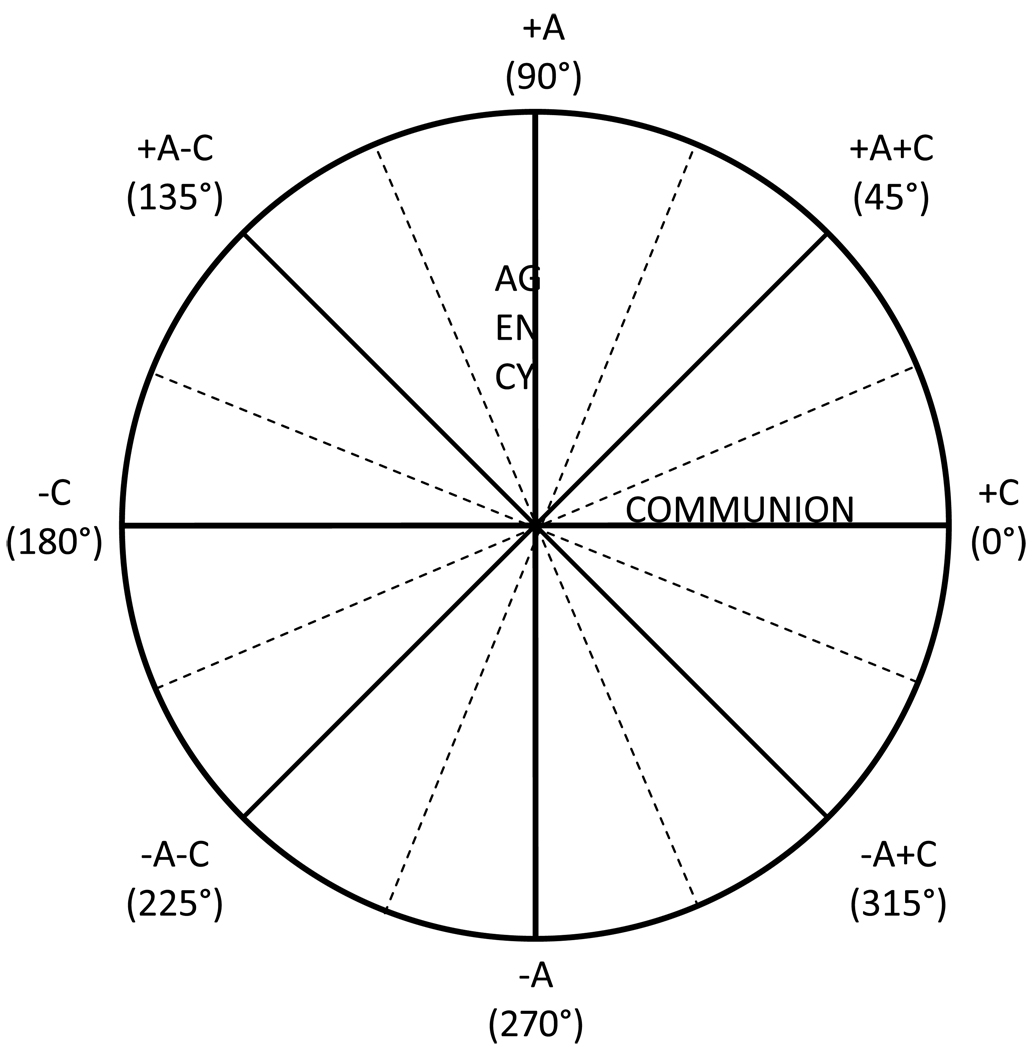

The IPC model represents a comprehensive structural model that is widely used to conceptualize and assess interpersonal dispositions in adults (e.g., Horowitz et al., 2006; Wiggins, 1979). The model is comprised of two orthogonal axes: a horizontal axis representing communion (i.e., friendliness, solidarity, and warmth) and a vertical axis representing agency (i.e., dominance, power, and control). Each point on the IPC is defined as a weighted combination of levels of both communion and agency, reflecting all combinations of agency and communion (Wiggins, 1979). IPC-based measures in adults are most often divided into eight scales, or octants, with four scales capturing the poles of agency vs. submissiveness and communion vs. separation, with the remaining four assessing the blends of these dimensions. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the general model. Agency and communion serve as the conceptual coordinates (Wiggins, 1991) for classifying the psychologically meaningful aspects of interpersonal functioning and by extension social goals (Locke, 2000; Pincus & Wright, 2010). Accordingly, conceptualizing social goals using an IPC framework with broad goal dimensions (i.e., agentic and communal goals) has the potential of assessing a wide range of social goals and the added utility of providing an organizing framework for social goals that are already identified in child research. For example, relationship and relationship maintenance (Chung & Asher, 1996; Erdley & Asher, 1996; Rose & Asher, 1999) goals can be conceptualized more broadly as communal goals, while control, maintaining an assertive reputation, and instrumental goals (Erdley & Asher, 1996; Rose & Asher, 1999) can be conceptualized more broadly as agentic goals (Ojanen et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

The Interpersonal Circumplex. Note. +A = Agentic; +A−C = Agentic-Separate; −C = Separate; −A−C = Submissive-Separate; −A = Submissive; −A+C = Submissive-Communal; +C = Communal; +A+C = Agentic-Communal.

Additionally, developmental researchers and theorists have urged for more continuity in scientific approaches to understanding the stability of interpersonal adjustment across developmental transitions (Shiner & Caspi, 2003) and an increased understanding of theoretical and empirical links between childhood characteristics and adult personality (Shiner, Masten, & Tellegen, 2002). Before empirically testing the question of whether personality traits evince continuity across childhood to adulthood, it is first necessary to examine whether it is possible to assess comparable traits across developmental periods (Shiner et al., 2002). Accordingly, adopting social goal models that synchronize with adult assessment may have the added advantage of assessing goal orientations across the life course. Given that the IPC has long been used to model social functioning in adults, conceptualizing social goals using this framework in childhood allows for greater continuity of interpersonal disposition assessment across developmental stages. The IGI-C measure notably answers this call for more continuity in models moving from childhood to adulthood by using a top-down (i.e., adult-based) approach to model construction to determine whether the validated IPC model in adulthood applies to younger developmental periods. This approach has the utility of drawing on established validated measures in adult work and provides a methodological link between highly similar theoretical structures of interpersonal functioning in both age groups, moving towards scientific cohesion in psychology.

In the current study, we revised the IGI-C (IGI-CR) in order to have a measure of social goals for children and adolescents with 1) more age and culturally appropriate instructions and items for use in an English-speaking sample, 2) an equal representation of items across all subscales, 3) a comprehensive assessment of circumplex structure, and 4) adequate validity across all subscales.

The IGI-C conceptualizes social goals as individual strivings when interacting with peers. We considered validity with respect to the degree to which the scales conform to a circumplex structure and with respect to convergent associations with peer avoidance, peer group identification, and cross-informant reports of aggression and affiliation using cosine curve fitting (Gurtman, 1992; Gurtman & Pincus, 2003). These constructs were chosen because they were believed to possess significant interpersonal content but that the content would be different across measures. Research suggests that aggressive youth place greater value on having control over peers and dominance, and are less concerned about peer affiliation and peer rejection compared to non-aggressive children (Lochman, Wayland, & White, 1993). In contrast, youth high in communal goals are more concerned with relationship maintenance, and seeking closeness and intimacy with peers (Lochman et al., 1993). Based on these findings, it was hypothesized that aggression would be associated with the separate and agentic aspects of interpersonal functioning. Perceived peer group identification and affiliation were expected to be associated most strongly with the communal side of the IPC, whereas peer avoidance was expected to be associated with the separate side of the IPC. Though specific hypotheses were not made regarding how social goals would differ for girls and boys, given reported gender differences in social goals, aggression, and social relationships (e.g., Jarvinen & Nicholls, 1996; Ojanen et al., 2005), we tested our hypotheses in the overall sample and across gender.

Method

Sample

This community sample of 387 early adolescents was part of a larger three-year longitudinal study investigating behavior problems as a risk factor for substance use initiation. The study utilized a random-digit-dial (RDD) sample of telephone numbers generated for Erie County, New York. Inclusion criteria included an 11 or 12 year-old son or daughter with no language or physical disability that would preclude them from understanding or completing the assessment, and a caregiver willing to participate. Families received $75 for participation. The participation rate for those completing the interview is 52.4%, well within the range of population-based studies requiring extensive subject involvement (Galea & Tracy, 2007).

Interviews were conducted in a research laboratory on a university campus. Before the interview, the caregiver was asked to give consent and the adolescent was asked to provide assent. Adolescents completed a battery of self-report measures including social goals. Caregivers also completed a variety of self-report measures reflecting their own behaviors (e.g., parenting practices) and their perception of their child’s behavior (e.g., aggression, affiliation). Data for this paper are taken from the first assessment and are based on adolescent and parent reports. Sample demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Selected Sample Characteristics

| Adolescents | Sample (n = 387) | Census 2000a |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| % Female | 55.0 | 48.3 |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 11.60 (.55) | |

| Range | 11–13 | 10–11 |

| Race | ||

| % Caucasian | 83.1 | 84.0 |

| % African American | 9.1 | 13.1 |

| % Hispanic | 2.1 | 3.5 |

| % Asian | 1.0 | 1.7 |

| % Other | 4.7 | 1.2 |

| Caregivers | ||

| Mean age (SD) | 42.6 (6.2) | NAb |

| Education | ||

| % Some High School | 2.9 | 17.1 |

| % High School Graduate | 14.2 | 29.9 |

| % Technical School or Some College | 24.7 | 28.5 |

| % College Graduate | 38.2 | 14.4 |

| % Graduate or Professional School | 20.0 | 10.1 |

| Family Characteristics | ||

| Median Annual Family Income | $70,000.00 | $49,490.00 |

| Family Composition | ||

| % Two-Parent | 76.0 | 54.0 |

| % Divorced/Separated | 12.1 | 8.6 |

| % Single-Parent/Never Married | 9.8 | 28.8 |

| % Other | 2.1 | 14.5 |

Note.

Census data for families with a child under age 18 living at home with parents in the 30–50 year old age range.

mean caregiver age is not available; however the age range was 30–50 years old.

Given our eligibility criteria, it would be inappropriate to compare our sample to the overall demographic characteristics of Erie County, NY. Accordingly, demographic information for a subpopulation of Erie County, NY that corresponds to the population from whence our sample came (i.e., families with a child under the age of 18 living in the home with parents in the 30 to 50 year old age range) is also presented in Table 1. Based on the U.S. Census Bureau (2009) report, the sample of respondents from Erie County compares well to the general population with only a few modest differences. The sample included a lower percentage of African-Americans (9% versus 13%), a higher percentage of multi-racial children (5% versus 1.5%), and higher percentage of married couple families (76% versus 54%).

Measures

Social goals

Social goals were assessed using a revised version of the IGI-C (Ojanen et al., 2005). The original IGI-C is adapted from an adult self-report measure, the Circumplex Scales of Interpersonal Values (CSIV; Locke, 2000), and included 33 self-report items (e.g., you feel close to others, you do not annoy others) with the stem, “When with your age-mates, how important is it for you that….” rated using a Likert-scale ranging from 0 (no importance for me at all) to 3 (very important to me). Each of the eight scales represents a different combination of agentic (dominance, status) and communal (belongingness, warmth) social goals: Agentic (+A; appearing dominant, independent), Agentic-Communal (+A+C; expressing oneself openly, being respected), Communal (+C; valuing solidarity with peers and belongingness), Submissive-Communal (−A+C; putting others’ needs first, valuing approval from others), Submissive (−A; going along with peers to avoid arguments or upsetting others), Submissive-Separate (−A−C; appearing distant and concealing positive feelings to avoid being rejected by others ), Agentic-Separate (+A−C; appearing to have the upper hand and getting even), and Separate (−C; appearing detached and not disclosing thoughts or feelings to others).

Several changes were made to the original measure to provide more culturally relevant instructions and items for an English-speaking sample. For example, the term “age-mates” was replaced with “peers” so that items were administered with the following instructions: “When with your peers, in general how important is it to you that…?” Similarly, the term “the others” was replaced with the term “peers” for several items to limit confusion. In addition, one item was deleted (you can keep the others at a suitable distance [−C]) and eight other items, also adapted from the CSIV, were added to the item pool in order to have a more equal representation of items per scale: 1) your peers do not tell you what to do (+A), 2) I feel I have control over my peers (+A−C), 3) your peers help you when you have a problem (+C), 4) you do what your peers want you to do (−A), 5) you don’t back down when there is a disagreement (+A), 6) you do not show your peers that you like them (−A−C), 7) you attack back (physically or verbally) when you are attacked (physically or verbally) (+A−C), 8) your peers come to you when they have a problem (+C). Finally, response options were expanded to a 5-point response-scale ranging from 0 (not at all important to me) to 4 (extremely important to me) to provide a wider range of responding.

We used Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to eliminate suboptimal items before testing the circumplex structure.1 PCA of the 40 items proceeded in an iterative fashion by first plotting the individual items in the two-dimensional IPC space (item responses were ipsatized to allow for easy plotting in 2 dimensional space) and evaluating individual item communalities, a review of item content on a rational basis, and individual item to scale correlations. The goal was to eliminate suboptimal items. Efforts initially focused on Communal and Submissive-Communal and Agentic and Agentic-Separate pairs of scales as they showed high degrees of overlap in the initial construction paper (Ojanen et al., 2005), although all octant scales were evaluated. The final set of 32 items (four per octant) retained on the IGI-CR is in the Appendix. Internal consistencies of the final eight scales were acceptable (α’s .68 to .80; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Intercorrelations and Reliabilities of the IGI-CR Octant Scales

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. +A | -- | 0.68 | |||||||

| 2. +A−C | 0.51** | -- | 0.69 | ||||||

| 3. −C | 0.34** | 0.45** | -- | 0.72 | |||||

| 4. −A−C | 0.47** | 0.36** | 0.45** | -- | 0.76 | ||||

| 5. −A | 0.50** | 0.30** | 0.32** | 0.69** | -- | 0.73 | |||

| 6. −A+C | 0.53** | 0.22** | 0.22** | 0.50** | 0.71** | -- | 0.80 | ||

| 7. +C | 0.56** | 0.22** | 0.13* | 0.48** | 0.64** | 0.74** | -- | 0.77 | |

| 8. +A+C | 0.67** | 0.38** | 0.24** | 0.47** | 0.58** | 0.62** | 0.69** | -- | 0.70 |

Note. N = 387. Interpersonal Goal Scales: +A = Agentic; +A−C = Agentic-Separate; −C = Separate; −A−C = Submissive-Separate; −A = Submissive; −A+C = Submissive-Communal; +C = Communal; +A+C = Agentic-Communal.

α = Cronbach’s alpha.

p <.05,

p <.001

The eight scales were used to assess psychometric properties and circumplex structure of the IGI-CR. In addition, dimensional scores were calculated for both agentic and communal goals following common IPC procedures (see Wiggins, Phillips, & Trapnell, 1989). The circumplex model suggests that the two dimensional scores should form two orthogonal dimensions (Wiggins et al., 1989). The bivariate correlations for dimension scores in our sample were consistent with this expectation (r = −.08, ns).

Child reports

Child-report of aggression was assessed using the aggressive behavior subscale of the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). These 17 items assessed self-reported aggressive behavior in the past six months including threatening to hurt others and physically attacking others. Response options were based on a 3-point Likert-scale ranging from “Not true,” “Somewhat or sometimes true,” and “Very true or often true.” Items were summed to create a scale score. The internal consistency for this measure was good (α = .80). The Perceived Peer Group Identity questionnaire (PPGI; Kiesner, Cadinu, Poulin, & Bucci, 2002) assesses feelings of involvement that an individual has toward a group to which he or she belongs (e.g., do you feel connected to the other members of this group). Responses were based on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from “No, not at all” to “Yes, very much.” The internal consistency (α = .74) for this measure was adequate in this sample. The avoidance subscale of the Child Social Preference Scale (CSPS; Coplan, Prakash, O’Neil, & Armer, 2004) includes 3 items and was used to assess social avoidance (i.e., I try to avoid other kids). The internal consistency was modest (α = .40), which may attributable to the low number of items.

Parent reports

In order to examine cross-informant relationships, parent-report of youth aggression and affiliation was assessed using the subscales of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire-Revised (EATQ-R; Ellis & Rothbart, 2001). The 7 items from the aggression scale reflect hostile and aggressive actions, including physical and verbal aggression and the 6 items from the affiliation scale reflect the desire for warmth and closeness. The EATQ-R uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Almost always untrue of my child” to “Almost always true of my child.” The internal consistency for both measures (α = .75 for aggression, α = .70 for affiliation) was adequate in this sample.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations of the IGI-CR octant scales and dimension scores, and other child and parent-report measures, are provided for the combined (N = 387), male (n = 174), and female (n = 213) samples in Table 3. Boys endorsed significantly higher levels of Agentic-Separate and Separate goals, whereas girls endorsed higher Submissive-Communal and Communal goals. On the summary dimensions, in general children described themselves as being somewhat submissive and communal in their social goals; however, boys endorsed less submissive and communal goals than girls. In terms of the non IGI-CR measures, boys endorsed more aggressive and avoidant behavior, whereas girls endorsed higher overall perceived peer group identification. Parent report suggests more affiliation among girls compared to boys, but no gender differences in aggression.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations of Scales in the Combined, Male, and Female Samples

| Combined | Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Name | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | es |

| +A | 2.09 | 0.80 | 2.13 | 0.75 | 2.06 | 0.83 | 0.09 |

| +A−C | 0.97 | 0.66 | 1.11 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.40* |

| −C | 1.51 | 0.85 | 1.68 | 0.87 | 1.37 | 0.82 | 0.37* |

| −A−C | 2.23 | 0.91 | 2.24 | 0.92 | 2.23 | 0.91 | 0.01 |

| −A | 2.38 | 0.80 | 2.32 | 0.79 | 2.43 | 0.81 | 0.13 |

| −A+C | 2.74 | 0.76 | 2.64 | 0.70 | 2.82 | 0.80 | 0.24* |

| +C | 2.68 | 0.77 | 2.52 | 0.72 | 2.81 | 0.78 | 0.38* |

| +A+C | 2.35 | 0.76 | 2.29 | 0.73 | 2.40 | 0.78 | 0.15 |

| Agency | −0.37 | 0.35 | −0.31 | 0.33 | −0.41 | 0.37 | 0.28* |

| Communion | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 0.61* |

| Aggression-YSR | 22.23 | 3.96 | 22.99 | 4.13 | 21.61 | 3.71 | 0.35* |

| Peer Group ID | 4.56 | 0.53 | 4.50 | 0.52 | 4.61 | 0.53 | 0.21* |

| Avoidance | 1.85 | 0.70 | 1.94 | 0.71 | 1.78 | 0.69 | 0.22* |

| Aggression-EATQ-R | 2.51 | 0.73 | 2.55 | 0.74 | 2.47 | 0.72 | 0.11 |

| Affiliation-EATQ-R | 4.06 | 0.58 | 3.92 | 0.58 | 4.17 | 0.55 | 0.44* |

Note. Combined N = 387, Males n = 174, Females n = 213. es = effect sizes based on Cohen’s d.

significant difference between males and females. Interpersonal Goal Scales: +A = Agentic; +A−C = Agentic-Separate; −C = Separate; −A−C = Submissive-Separate;−A = Submissive; −A+C = Submissive-Communal; +C = Communal; +A+C = Agentic-Communal.

Evaluation of Circumplex Structure

To evaluate the circumplex structure of the IGI-CR, we employed two alternative approaches beginning with a non-parametric test of hypothesized order relations and following with highly constrained structural equation models (SEM). Guttman’s (1954) initial description of a circumplex was based on what was termed a “circulant” pattern in the correlations among a set of tests. The circulant pattern, or circumplex, can be defined using the geometry of a circle with the tests arranged around the perimeter. The highest correlations occur between adjacent scales (i.e., of similar content) and correlations decrease as a function of the angular distance between scales (i.e., as content similarity decreases), with those scales at opposite angles (i.e., 180°) showing strong negative correlations. Thus, the correlation between any two scales in the circumplex array is defined as a function of its angular distance on the circumference of the hypothesized circle. In a perfect circumplex, the scales all have equal communalities (i.e., uniform radius) and are equally spaced (i.e., separated by the same angle).

The first approach we used to evaluate the circumplex was RANDALL (Tracey, 1997), a program based on Hubert and Arabie’s (1987) randomization test of hypothesized order relations. This approach examines the pattern of correlations between the scales in terms of their relative magnitude. The circulant pattern described above predicts that correlations between scales that are placed next to each other on the circle are higher than those two places away, etc. In an 8-scale circumplex this produces 288 hypothesized order predictions. The number of these predictions met in the observed correlation matrix is compared with a distribution of the number of predictions created by all possible permutations arising from random patternings of the matrix (Tracey, 1997). To aid in interpretation, Hubert and Arabie (1987) suggested the use of the correspondence index (CI) reflecting the number of predictions met minus those violated divided by the total number of predictions. Values of the CI range from −1.0 to 1.0, with 0 reflecting 50% of the predictions met. This was the approach adopted by Ojanen et al. (2005) in the development of the IGI-C; therefore we conducted the same analyses to allow for a comparison to the original Finnish measure.

Results based on the analyses conducted in RANDALL indicated that the full sample had good fit to a circumplex pattern with 271/288 predictions met (CI = .89, p < .001). We also evaluated the correspondence by gender. The IGI-CR demonstrated equivalent fit across gender (males CI = .87, p < .001; females CI = .89, p < .001). This non-parametric approach to establishing circumplex structure also suggests that the scales of the IGI-CR conform to a circumplex. This approach assumes equal spacing and equal communality of scales but provides no formal test of these assumptions.

The second approach we used to evaluate the circumplex employed CIRCUM (Browne & Cudeck, 1992), a specialized SEM program for circumplex models. CIRCUM provides a confirmatory test of circumplex models of varying constraints. In the most constrained models the structure that is tested is one of equal communalities for all scales (i.e., the circumplex has an equal radius at each scale point) and equal spacing between the scales (i.e., in an 8-scale circumplex the scales fall 45° apart). However, the equality constraints placed on the radii and the spacing of the scales can each be relaxed independently to test less stringent models. Thus, models can be tested that have equal radii but not spacing, and vice versa, and finally, a model that does not impose either constraint, but instead tests the general ordering of the scales. CIRCUM functions by estimating a correlation matrix based on a Fourier series which is compared to the observed correlation matrix to determine fit of the model (see Fabrigar, Visser, & Browne, 1997 for a non-technical primer of the method). The researcher is required to define the number of components (m) in the Fourier series. It is common to specify m = 3 in an 8-scale circumplex (Gurtman & Pincus, 2003; see Browne, 1992 equation 34 for the general form of the equation) and this was the approach adopted here. CIRCUM generates estimates for angular location in degrees and the communality value for each variable (for those models that do not constrain these values). An additional useful piece of information provided is the minimum correlation at 180°. In a circumplex correlation matrix of all positive values this would be expected to approach 0.0, or −1.0 in the case of a matrix with negative values. However, in practice it is often the case that this value is substantially larger than the theoretical minima due to systematic biases in the data. An important source of systematic bias would be a general factor. Therefore, a minimum correlation value at 180° substantially larger than 0.0 might suggest that a substantive general factor is contained within the circumplex inventory and should be interpreted.

In addition to this output, CIRCUM provides the maximum likelihood discrepancy function, chi-square statistic, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1992) to evaluate model fit. In addition, we calculated the adjusted goodness-of-fit (AGFI) index (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1986) in order to have multiple indexes to evaluate model fit. Values of the RMSEA below .08 are generally considered acceptable, whereas good fit for the AGFI is indicated by values above .90. In addition, CIRCUM provides the 90% confidence interval associated with the RMSEA. These are parsimony adjusted fit indexes which account for complexity of the estimated model and number of estimated parameters. More constrained models are nested within the less constrained models and can be compared using the chi-square difference test (Δχ2) as with all nested SEM based models (Bollen, 1989).

Table 4 summarizes the fit of all four possible models (i.e., equal radius and spacing, equal radius or equal spacing, and an unconstrained model) in the combined sample and by gender. In addition, Δχ2 values are provided to allow for comparisons across models. The approach adopted here is to compare the less constrained models to the more constrained models. In Table 4, Models 2 and 3 are compared to Model 1, whereas Model 4 is compared to the best fitting of 2 and 3. Table 5 contains the estimates of the angular locations and communalities of the scales for models when appropriate. In the combined sample, the RMSEA and AGFI suggested that the fully constrained model did not have acceptable fit. The AGFI suggested good and generally equivalent fit of the less constrained models, whereas the RMSEA remained marginal but also generally equivalent for the less constrained models in the combined sample. A consideration of the data presented in Table 5 would suggest that Models 3 and 4 have roughly equal average angular discrepancies between the target angles and estimated variable locations; however, Model 4 had significantly better fit based on the Δχ2 test. Average angular discrepancy was 28° for this model, with an average communality value of .88. The minimum correlation at 180° was .35 consistent with the interpretation of a large first-factor. Indeed, and examination of the correlation matrix presented in Table 3 confirms this. The fully constrained model represents a highly stringent test of model fit that is unlikely to be met by actual collected data, and failure to meet this criterion often has little practical significance (Gurtman & Pincus, 2000; Hafkenscheid & Rouckhout, 2009). However, the fit of the less constrained models was roughly equivalent in the combined sample with a slight preference for Model 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Fit Statistics for CIRCUM Analyses in the Combined, Male, and Female Samples

| RMSEA | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radius | Spacing | df | P | FML | χ2 | RMSEA | 90% CI | AGFI | Δχ2 | p | |

| Combined | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | Equal | Equal | 24 | 12 | .427 | 164.82 | 0.123 | .106-.141 | 0.86 | -- | -- |

| Model 2 | Unequal | Equal | 17 | 19 | .167 | 64.46 | 0.085 | .063-.107 | 0.92 | 100.36 | < .001 |

| Model 3 | Equal | Unequal | 17 | 19 | .166 | 64.08 | 0.085 | .063-.107 | 0.92 | 100.74 | < .001 |

| Model 4 | Unequal | Unequal | 10 | 26 | .107 | 41.30 | 0.090 | .063-.119 | 0.91 | 22.78 | < .01 |

| Males | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | Equal | Equal | 24 | 12 | .459 | 79.41 | 0.115 | .088-.144 | 0.85 | -- | -- |

| Model 2 | Unequal | Equal | 17 | 19 | .113 | 19.55 | 0.029 | .000-.078 | 0.94 | 59.86 | < .001 |

| Model 3 | Equal | Unequal | 17 | 19 | .141 | 24.39 | 0.050 | .000-.092 | 0.93 | 55.02 | < .001 |

| Model 4 | Unequal | Unequal | 10 | 26 | .068 | 11.76 | 0.032 | .000-.092 | 0.94 | 7.79 | .35 |

| Females | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | Equal | Equal | 24 | 12 | .427 | 90.52 | 0.114 | .090-.140 | 0.86 | -- | -- |

| Model 2 | Unequal | Equal | 17 | 19 | .192 | 40.70 | 0.081 | .049-.113 | 0.90 | 49.82 | < .001 |

| Model 3 | Equal | Unequal | 17 | 19 | .166 | 35.19 | 0.071 | .037-.104 | 0.92 | 55.33 | < .001 |

| Model 4 | Unequal | Unequal | 10 | 26 | .129 | 27.35 | 0.091 | .051-.132 | 0.89 | 7.84 | .35 |

Note. Combined N = 387, Males n = 174, Females n = 213. df = Degrees of Freedom; P = number of estimated parameters FML = maximum likelihood discrepancy function; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CI = Confidence Interval; AGFI = Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index.

Table 5.

Estimated angles and communalities from CIRCUM models.

| Octant | +C | +A+C | +A | +A−C | −C | −A−C | −A | −A+C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angles | ||||||||

| Target Angle | 0° | 45° | 90° | 135° | 180° | 225° | 270° | 315° |

| Combined | ||||||||

| Model 3 | 0° | 27° | 56° | 124° | 198° | 281° | 316° | 344° |

| Model 4 | 0° | 16° | 58° | 140° | 195° | 280° | 324° | 348° |

| Males | ||||||||

| Model 3 | 0° | 19° | 30° | 78° | 179° | 310° | 329° | 353° |

| Model 4 | 0° | 42° | 69° | 135° | 171° | 243° | 287° | 343° |

| Females | ||||||||

| Model 3 | 0° | 28° | 60° | 122° | 199° | 275° | 315° | 341° |

| Model 4 | 0° | 17° | 58° | 133° | 201° | 279° | 324° | 345° |

| Communalities | ||||||||

| Combined | ||||||||

| Model 2 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.88 |

| Model 4 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.86 |

| Males | ||||||||

| Model 2 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.83 |

| Model 4 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.82 |

| Females | ||||||||

| Model 2 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.91 |

| Model 4 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

Note. Model numbers refer to models presented in Table 4. Model 1 and 2 have fixed angular locations; Models 1 and 3 have fixed communalities. All angles presented in degrees.

Interpersonal Goal Scales: +A = Agentic; +A−C = Agentic-Separate; −C = Separate; −A−C = Submissive-Separate;−A = Submissive; −A+C = Submissive-Communal; +C = Communal; +A+C = Agentic-Communal

To remain consistent with RANDALL analyses, CIRCUM was applied to the pattern of correlations observed in each gender. Results generally mirror those in the combined sample, with some important differences. For both genders the fully constrained model had poor fit. However, for the boys Model 2 clearly provided the best fit. It had a non-significant model χ2 (df =17, χ2 =19.55, p > .05) and accordingly had good fit as suggested by the RMSEA and AGFI. Model 2 provides a highly constrained test in which the angular locations are held to be equal. The communalities found in Table 5 demonstrate that although they cannot simultaneously be constrained with the angular locations, the estimated communalities are comparable across Models 2 and 4. The average communality value for this model was .80. The minimum correlation at 180° was .65. For the girls, among the less constrained models, considering both fit statistics and the estimated angular locations and communalities, the preferred model is Model 3 based on the RMSEA and AGFI which are both in acceptable ranges and the best of the estimated models. In this model, the average discrepancy between target and estimated angles is 25°. The minimum correlation at 180° was .31. In summary, the results of RANDALL and CIRCUM analyses converge to suggest that the IGI-CR generally conforms to a circumplex. However, there is clear room for improvement vis-à-vis circumplex structure, especially as it pertains to girls. Of note is that for boys the structure is more robust than for girls and the combined sample, achieving very good fit statistics, and angular placements that can be constrained to be equal and still maintain good model fit. For the girls the angular locations cannot be constrained to equality, although the best model does have equal communalities. In addition, it would seem, based on the minimum correlations at 180° that there is a first factor driving the positive correlations across the scales. Importantly, the model fit achieved in CIRCUM in all samples compares favorably to established and long-used circumplex measures evaluated in the same way (e.g., Acton & Revelle, 2002; Gurtman & Pincus, 2000).

Construct Validation and the IGI-CR’s Nomological Net

The previous results support acceptable circumplicial properties of the IGI-CR and provide evidence for the construct validity of this measure by demonstrating that its scales adhere to the highly articulated structural model of interpersonal tendencies (Campbell & Fiske, 1959; Guttman, 1970). In a final set of analyses we sought to further test the construct validity of the newly revised IGI-CR by association with external constructs with putative interpersonal content and cross-informant relationships: aggression (self- and parent-report), perceived peer group identification (self-report) and affiliation (parent-report), and social avoidance (self-report). Circumplex measures, due to the well-defined structure of scale interrelations, are by definition precise nomological nets (Gurtman, 1992). This structure, once known to exist, can serve as the scaffolding for establishing the interpersonal aspects of other constructs and measures in interpersonal space. To build on this description, the predicted pattern of correlations of other (presumably interpersonal) constructs should mirror this pattern of associations whereby a strong association with the content of one octant would presume lesser, but similarly strong associations with adjacent octants, with decreases in associations as the angular distance increases. For example, if another measure of interpersonal content were to be correlated with the eight scales of a circumplex, and its highest correlation were with the Agentic scale, it would be anticipated that the next highest correlations would be with the Agentic-Communal and Agentic-Separate scales (each at 45°), followed by the Communal and Separate scales (90°), and so on. This is because the scales of a circumplex measure are not only mathematically, but semantically and conceptually constrained to provide this pattern, and it should be repeated in external yet related interpersonal measures.

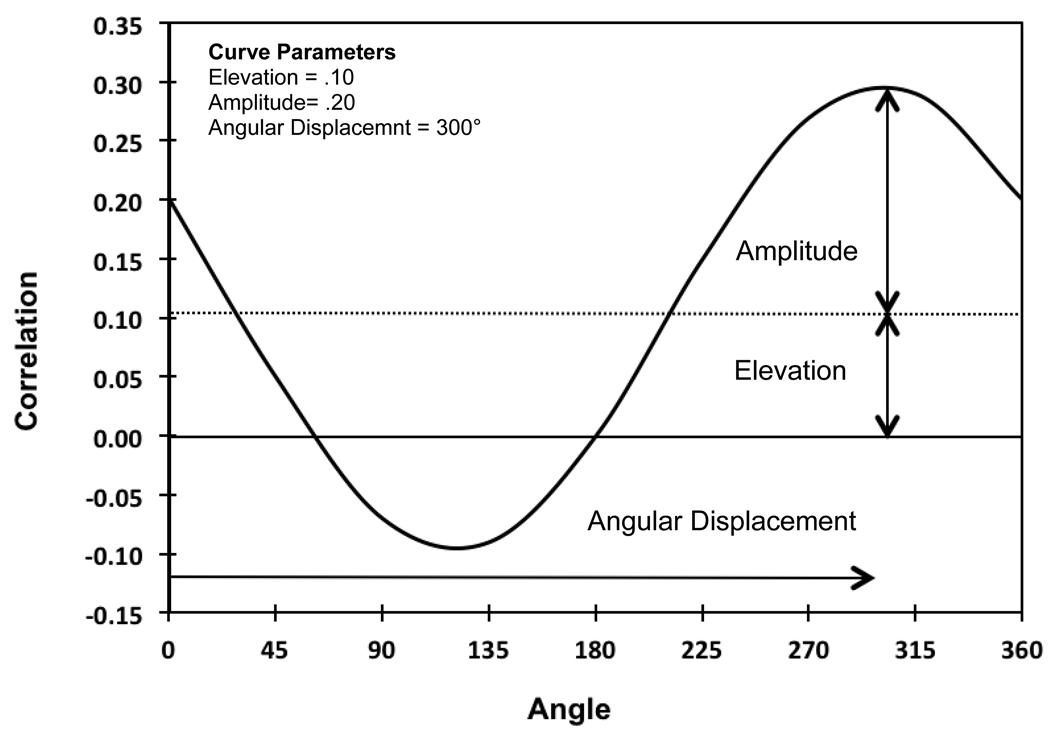

This pattern of associations, if taken as correlations and graphed on a line would produce a sinusoidal pattern—a cosine function to be precise (Wiggins, Steiger, & Gaelick, 1981). The structural summary approach for analyzing circumplex data evaluates the interpersonal features of an external construct by comparing the observed pattern of correlations to the eight scales with the predicted pattern generated by a perfect cosine curve (see Gurtman, 1992; Gurtman & Pincus, 2003; Wright, Pincus, Conroy, & Elliot, 2009 for detailed descriptions of the method). This method reduces the observed pattern of correlations to a set of structural parameters for a cosine curve that include the angular displacement (i.e., the peak of the curve, and core interpersonal content), amplitude (i.e., how differentiated is the pattern of correlations), and elevation (i.e., average correlation). Figure 2 graphically presents an example of a cosine wave and associated structural parameters. In this visual example, a perfect cosine pattern is presented with an elevation of .10, amplitude of .20, with an angular displacement of 300°. In practice, an ideal cosine wave based on the structural summary parameters derived from the observed correlations can be compared to the observed values to obtain a goodness-of-fit index which has been labeled R2. The maximum value of this R2 is constrained to 1.00, with values above .80 indicating good fit to a cosine curve and conformity with the predicted pattern of interpersonal content (Gurtman & Pincus, 2003).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the cosine curve parameters associated with the structural summary method.

We examined associations of social goals with aggression, peer group identification, affiliation, and avoidance using the method described above. We hypothesized that these criterion variables would have prototypical interpersonal profiles (i.e., high R2) especially for self-report measures, but that the angular displacements would differ considerably: aggression falling in the Agentic-Separate octant, perceived peer group identification and affiliation falling in the Communal octant, social avoidance falling in the Separate octant. Finally, bivariate correlations on these criterion variables, and Agentic and Communal dimensional scores were evaluated. Gender differences were evaluated by assessing these correlations separately for males and females. The pattern of correlations of each measure with the IGI-CR and structural summary parameters for the combined sample, boys, and girls are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Octant Correlations and Structural Summary Parameters for External Variables in Combined Sample and by Gender

| +A | +A−C | −C | −A−C | −A | −A+C | +C | +A+C | Agencya | Communiona | Angle | Elevation | Amplitude | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined | ||||||||||||||

| Aggression | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.21 | −0.11 | 125 | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.98 |

| PPGI | 0.19 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.26 | −0.15 | 0.31 | 340 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.95 |

| Avoidance | −0.17 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −0.24 | −0.30 | −0.34 | −0.20 | 0.14 | −0.33 | 161 | −0.15 | 0.19 | 0.93 |

| Aggression-P | −0.10 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.14 | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.12 | 146 | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.80 |

| Affiliation | 0.10 | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.17 | 349 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.79 |

| Boys | ||||||||||||||

| Aggression | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.16 | 153 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.80 |

| PPGI | 0.17 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.21 | −0.15 | 0.28 | 339 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.90 |

| Avoidance | −0.18 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.20 | −0.20 | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.17 | 165 | −0.11 | 0.09 | 0.68 |

| Aggression-P | −0.11 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.00 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.14 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.11 | 213 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.63 |

| Affiliation | 0.05 | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 56 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.56 |

| Girls | ||||||||||||||

| Aggression | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.14 | −0.21 | −0.13 | −0.15 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 92 | −0.06 | 0.13 | 0.96 |

| PPGI | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.29 | −0.13 | 0.30 | 343 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.94 |

| Avoidance | −0.17 | 0.10 | 0.06 | −0.11 | −0.29 | −0.36 | −0.43 | −0.27 | 0.18 | −0.42 | 160 | −0.19 | 0.25 | 0.95 |

| Aggression-P | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.12 | −0.26 | −0.23 | −0.12 | −0.06 | 0.23 | −0.10 | 118 | −0.11 | 0.12 | 0.78 |

| Affiliation | 0.17 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.15 | −0.08 | 0.16 | 337 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.74 |

Note. PPGI = Perceived Peer Group Identity. Aggression-P= Parent-report; +A = Agentic;+A−C = Agentic-Separate;−C = Separate;−A−C = Submissive-Separate;−A = Submissive;−A+C = Submissive-Communal;+C = Communal;+A+C = Agentic-Communal,

Dimensional scores. All correlations < .13 significant at p <.05.

Combined sample

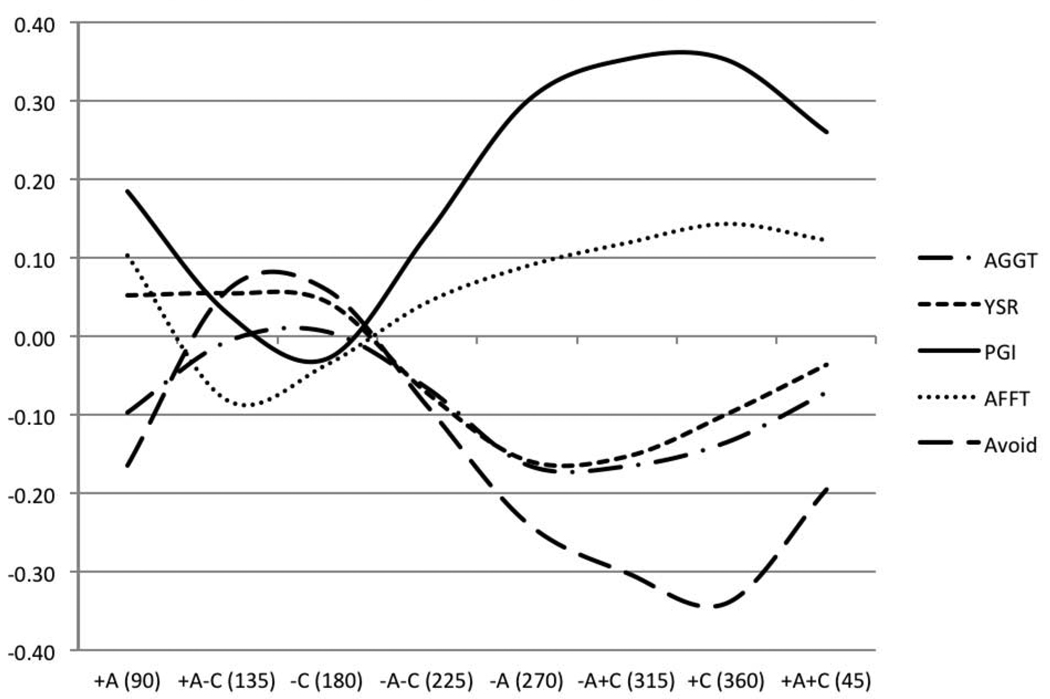

The combined sample correlations are displayed in Figure 3. As is readily apparent in the figure, the structural summary parameters for perceived peer group identification suggest a highly prototypical interpersonal profile, with moderate elevation and differentiation, with a displacement in the Communal octant. Although the amplitude for parent report of child affiliation is modest, the structural summary parameters are consistent with the child report of perceived peer group identification in that there is angular displacement in the Communal octant. These results suggest that, as expected, perceived peer group identification and parent-reported affiliation are associated with communal social goals, and that the interpersonal content in these constructs are well-summarized by social goal content of the IGI-CR (i.e., high R2). The presence of a moderate elevation with only moderate differentiation suggests that perceived peer group identification and affiliation may be broadly related to having social goals.

Figure 3.

Plot of the Correlations of External Measures with the IGI-CR. Note. +A = Agentic; +A−C = Agentic-Separate; −C = Separate; −A−C = Submissive-Separate; −A = Submissive; −A+C = Submissive-Communal; +C = Communal; +A+C = Agentic-Communal; AGGT = Aggression, Parent-Report; YSR = Aggression, Child-Report; PGI = Peer Group Identification; AFFT = Affiliation; Avoid = Avoidance.

Parent and self-report of aggression also exhibit prototypical profiles, with no appreciable elevation, and only modest differentiation, with an angular displacement in the Agentic-Separate octant. Although the angular displacement is where it would be expected for aggression, an examination of the correlation pattern suggests that aggression is not aligned with strong Agentic and Separate goals, but rather aligned with a lack of Communal and Submissive-Communal goals. Lastly, social avoidance exhibits a generally prototypical profile with no appreciable elevation, with an angular displacement in the Separate octant, as expected.

Gender differences

The results for perceived peer group identification are highly consistent across gender. The pattern of correlations and structural summary parameters summarized in Table 6 are virtually identical, with only differences occurring in magnitude. The structural summary parameters and pattern of correlations for parent-report of affiliation are similar to perceived peer group identification, but only for females. Consistent with self-report of peer group identification, the core interpersonal content of parent-report of affiliation is belongingness. For males, affiliation as reported by parents, does not exhibit a highly prototypical profile and is not well summarized by social goal content (i.e., R2 is modest). This suggests that our measure of social goals may not have a strong association with male affiliation as reported by parents. The pattern of correlations and structural summary parameters for social avoidance are also very similar across gender, with differences occurring in magnitude.

Clear gender differences emerge for aggression. In both boys and girls, self-reported aggression shows prototypical profiles, but discrepant angles with boys falling in the Agentic-Separate bordering on the Separate octant and girls falling squarely in the Agentic octant. The low elevation of each profile suggests that aggression is not associated with strong social goals. An analysis of the individual correlation suggests that it is a departure (i.e., negative association) from the normative pattern of Submissive-Communal social goals that is predictive of aggression in children. Aggression in boys is predicted by a lack of primarily communal goals, whereas for girls it is low submissiveness or compliance that is associated with aggression. For parent-reported aggression, girls are demonstrating a more prototypical profile compared to males. The low elevation in these profiles is consistent with self-reported aggression, where aggression does not seem to be associated with strong social goals (i.e., R2 is modest), especially among boys. Finally, consistent with self-report, the core interpersonal content of parent-report of aggression for girls is a lack of submissiveness.

Dimensional scores

Correlations of the Agentic and Communal dimensional scores with criterion variables are also presented in Table 6. Overall, Agentic dimensional scores were positively correlated to self-reported aggression and negatively correlated to perceived peer group identification. There was also evidence for a slight positive association between Agentic dimensional scores and avoidance. In contrast, Communal dimensional scores were negatively correlated to avoidance and self-reported aggression and positively correlated to perceived peer group identification and affiliation. Results suggest gender differences in these correlations. Namely, Agentic dimensional scores were not correlated to either measure of aggression, avoidance, perceived peer group identification or affiliation for boys, but were positively correlated to both measures of aggression and avoidance and negatively correlated to perceived peer group identification for girls. In contrast, Communal dimensional scores were positively correlated to perceived peer group identification and negatively correlated to avoidance for boys and girls. Communal dimensional scores were not correlated to aggression among girls and were negatively correlated to aggression in boys. Affiliation was positively correlated to communal dimensional scores for females, but not correlated among boys.

Discussion

There is current theoretical interest in the role children’s social goals play in understanding social adjustment (e.g., Crick & Dodge, 1994; Little, Jones, Henrich, & Hawley, 2003; Ojanen et al., 2005; Prinstein & Cillessen, 2003); yet, few valid measures exist that broadly assess social goals among English-speaking youth. The primary aim of the current study was to use the interpersonal circumplex model (Locke, 2000) to extend psychometric work on the IGI-C to develop a revised version of this measure that would improve the psychometric properties and that would be appropriate for English-speaking youth. Such a measure is important as it would expand our understanding of children’s social behaviors, identify general interpersonal proclivities across contexts, and synchronize child and adult literatures allowing for lifespan developmental models of social goals.

The IGI-CR had acceptable internal consistency. In general, children placed greater value in communal goals compared to agentic goals. This is consistent with findings suggesting that children and adolescents give their highest ratings on communal or prosocial goals compared to agentic goals (Ojanen et al., 2005; Rose & Asher, 1999). Attachment theory suggests that there is a persistent human drive to form and maintain intimate, positive and cohesive interpersonal relationships (Bowlby, 1988), and our findings support this notion. This finding is also in line with the belongingness theory suggesting that across males and females there is a persistent human drive to form and maintain positive and cohesive interpersonal relationships (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Overall, girls endorsed more communal and submissive goals, while boys endorsed more agentic and separate goals. These findings are largely in accordance with prior findings on children’s social goals (Chung & Asher, 1996; Ojanen et al., 2005; Rose & Asher, 1999) and gender role development in early adolescence (Maccoby, 1990). Traditionally boys are encouraged to be dominant, separate, power-oriented, and independent; while girls are socialized to be polite, interdependent, and to endorse more affiliative traits (Cross & Madson, 1997; Maccoby, 1990).

Overall, analyses assessing the circumplex structure of the IGI-CR using RANDALL and CIRCUM suggest that social goals as assessed using the IGI-CR fit a circumplex structure. More specifically, the randomization test of order suggested that the IGI-CR (CI = .89) was comparable to the original IGI-C (CIs = .73-.82; Ojanen et al., 2005) and to other adult measures of interpersonal goals such as the CSIV and the IGI (CIs = .91 and .76, respectively; Locke, 2000). In addition, based on these analyses, the IGI-CR provided a good fit across gender and provided a comprehensive range of interpersonal content. The IGI-CR also performed acceptably in the more stringent tests of structure as assessed by SEM in CIRCUM, comparing favorably to established measures (Acton & Revelle, 2002; Gurtman & Pincus, 2000). However, it appears as though the spacing of scales is more uniform in boys and that for girls some of the scales deviate from their predicted locations. Notably, the scales associated with the affiliative side of the circle tend to be less differentiated (see Table 5). Despite potential limitations created by the unequal spacing of scales, the structural summary method was able to achieve excellent fit to a cosine curve with external measures, lending credence to the argument put forth by previous researchers (Gurtman & Pincus, 2000) that minor deviations from ideal circumplex fit may not be of great practical significance. Finally, the CIRCUM analyses suggest the presence of a large general factor as is often found in IPC measures with evaluative content. The CSIV, the original adult measure upon which the IGI-C and IGI-CR are based also possesses a large general factor, presumably of the same content. However, little research has investigated its substantive meaning. Given the general instructions associated with the stem of the IGI-CR, and the pattern of associations with perceived peer group identification, one likely meaning is overall investment in the social domain. Nevertheless, future research is required for a full understanding and appreciation of the meaning of this first factor from this group of measures.

In order to further assess construct validity of the IGI-CR, relationships between other constructs with putative interpersonal content (i.e., perceived peer group identity, avoidance, affiliation and aggression) across multiple informants were analyzed using the structural summary approach and by calculating dimensional scores of social goals. It was expected that self-report of perceived peer group identification and avoidance would perform the best using this approach given that these measures are most clearly linked to interpersonal content. In addition, it was expected that parent scales would perform the worst given that they reflect cross-informant reports. Overall, the relationships were in the predicted direction.

Perceived peer group identification and affiliation were positively correlated to Communal dimensional scores and perceived peer group identification was negatively correlated to Agentic dimensional scores. Avoidance was negatively correlated to Communal dimensional scores, as expected; however, there was evidence for a slight positive association between social avoidance and Agentic dimensional scores. This was not expected, given that in the original measure there was evidence for a negative correlation between Agentic dimensional scores and withdrawal behaviors (Ojanen et al., 2000). Yet, it is important to note that the measure of withdrawal used by Ojanen et al. (2000) reflects greater passivity and submissiveness (e.g., is timid and shy). Our measure of avoidance did not include items reflecting shyness or social anxiety; rather, it reflects a slightly more assertive and dominant social behavior of actively avoiding peer contact.

Consistent with our expectation, the interpersonal content of perceived peer group identification and social avoidance is well summarized by social goal content as reflected in the high R2. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that relationship maintaining goals are strongly related to expressed wishes for being with others and positive friendship quality (Rose & Asher, 1999; Ojanen et al., 2005). Furthermore, our results suggest that perceived peer group identification and social avoidance are largely consistent across boys and girls, as evidenced by highly similar structural summary profiles across gender. This suggests that individuals who value belongingness and feeling connected to their peer group are more likely to endorse strong communal goals. This pattern is consistent with parent-report of affiliation, but only for females. Our measure of social goals may not have a strong association with male affiliation as reported by parents. In contrast, those individuals who value avoiding others lack primarily Communal goals, and this is consistent across gender.

The relationship between the dimensional scores of Agentic and Communal social goals and self-report of aggression were consistent with our original hypotheses. Overall, self-report of aggression was positively correlated to Agentic dimensional scores and negatively correlated to Communal dimensional scores. Although parent-report of aggression was not significantly correlated with either Agentic or Communal dimensional scores, self- and parent-report of aggression both demonstrated angular displacement in the Agentic-Separate octant as expected. Research on aggressive motivation suggests that children and adolescents may use aggressive behavior as a way to achieve positions of control and dominance by intimidating others even if it may negatively impact the friendship (Prinstein & Cillessen, 2003). In addition, aggressive children generally value appearing separate as reflected in their low ratings to goals associated with working things out and getting along with peers compared to non-aggressive children (Erdley & Asher, 1996).

A more nuanced picture emerged for aggression in the structural summary analysis. Results indicated that self- and parent-report of aggression in our sample is not characterized by strong agentic and separate goals, but rather a lack of endorsing communal and submissive-communal goals. This suggests that individuals use aggression as a means to not appear submissive or passive and to avoid appearing like they value acceptance from their peers. Research on motivational factors in the engagement of aggressive behaviors in adolescence has tended to focus on specific goals (i.e., dominance and revenge goals) which often provide “muddy” and “undifferentiated goal structure” (Lochman et al., 1993). Our findings suggest that current research on aggressive motivations may be limited by this restricted range of social goal assessment and that a broad measure of social goal dimensions has the utility of assessing more fine-grained interpersonal proclivities (e.g., submissiveness and separateness) that cannot be captured through traditional measures of social goals. These analyses highlight the considerable power of a fully articulated model of interpersonal functioning provided by the IPC, allowing for the unpacking of broad dimensions of functioning in a structurally coherent manner. This initial evaluation of aggression in the context of a comprehensive model of social goals has generated testable hypotheses for future research.

Given the extensive literature demonstrating strong gender effects in both the form and function of aggression (Crick, 1997; Zimmer-Gembeck, Geiger, & Crick, 2005), separate analyses were conducted to examine possible gender differences. It is important to highlight that the elevation of profiles for both genders is low, suggesting that aggression is not associated with strong social goals, particularly for boys. Furthermore, the lack of strong associations across social goals and aggression is compounded by cross-informant relationships. That is, a prototypical profile did not emerge for parent-report of aggression for boys. Dimensional score analyses suggest that self- and parent-report of aggression was positively correlated with Agentic dimensional scores for girls but not for boys. In addition, Communal dimensional scores were negatively correlated with self-report of aggression for boys, but were not correlated to Communal dimensional scores for girls. This suggests that aggression may function as a means for obtaining dominance and independence among peers in girls, while it may function as a means of appearing separate and distancing oneself from peers in boys.

There were clear gender differences in cosine curve analyses for self-report of aggression primarily in angular displacement. The findings suggest that the core interpersonal content of aggression for boys is a lack of submissive and communal goals and that motivation to engage in aggressive behaviors in males may be more complex and multifaceted than has been traditionally conceptualized. Males may not be purely motivated to engage in aggressive behaviors to achieve dominance and revenge goals (Cross & Madson, 1997), but may also value not appearing passive or diffident compared to less aggressive boys.

In contrast, the core interpersonal content of self- and parent-report of aggression for girls is a lack of submissiveness. Girls may be more concerned that aggressive behaviors may lead to greater peer rejection and view negative interpersonal consequences as the worst outcome of aggressive behavior (Cross & Madson, 1997); therefore, girls may not value appearing separate and detached compared to boys. Overall, these gender differences suggest that continued research exploring the role of general social goals in gender specific motivational processes in engaging in aggressive behaviors may offer important advances in future research.

Although this study made several important contributions to the literature, it is important to note several limitations. Findings should not be generalized to samples with demographic characteristics different from our sample. For example, although our sample was representative of the county from which it was drawn, it was largely a Caucasian sample, and social goals may operate differently across racial/ethnic groups. We did not have adequate group sizes to test for such differences. It will be important for future research to assess the validity of the IGI-CR among more diverse racial/ethnic groups. Though a notable strength of this study was the inclusion of cross-informant relationships, as expected parent-reports of aggression and affiliation did not perform as well as self-reports. More specifically, elevation on the profiles of both parent-report measures were low across gender and a prototypical profile (a modest R2) did not emerge for parent-report of aggression for boys. These findings may suggest that parents may not be good reporters of aggression in boys. However, our parent-report measure of aggression had good internal consistency (α = .77) among boys and was significantly correlated (r = .30, p <.0001) with self-report of aggression among boys. It seems that the modest profile in parent-report of aggression may be a function of social goals generally having a weak association with aggression for boys in our sample, and these weak associations are compounded when testing cross-informant associations. Boys’ overt aggressive behaviors may not be representative of some internal states, such as social goals.

It is also important to mention that there are multiple methodologies for addressing lifespan developmental models of human functioning. This study used a top-down approach where items were obtained from a validated adult measure (CSIV; Locke, 2000). A bottom-up approach which aims to take into account a child-specific perspective, may tap into more specific aspects of social goals that are unique to this developmental period and this may be a useful direction for future research. In addition, given that the same sample was used to construct the interpersonal goal scales and to test the psychometric properties of the scales, it will be important that future research replicate these findings in other samples. Furthermore, given that these scales were developed and validated using an American sample of youth, it will be important for research to assess the validity of the IGI-CR in other English-speaking countries outside of the United States. It is also unclear whether the circular structure of children’s social goals found in the current study will generalize to other contexts (e.g., parent-child interactions); therefore, the applicability of children’s interpersonal goals across other types of social contexts could be the focus of future research.

Our study was also limited to a broad assessment of aggression. This form of aggression may not capture typical aggressive behavior in girls compared to gender normative forms of aggression (i.e., relational aggression). Accordingly, our results should not be generalized to narrowly conceptualized domains of aggression. Future research assessing multiple forms of aggression may help clarify gender differences in the associations between social goals and heterogeneous patterns of aggressive behaviors exhibited by adolescents. Furthermore, examining specific forms of aggression may provide a greater understanding in the nuances of adolescent social motivations for engaging in aggressive acts. For example, physical aggression may be more strongly related to agentic goals while relational aggression may be more strongly related to separate goals.

Overall, this study contributes to a broader life span perspective on the assessment of interpersonal goals by demonstrating that social goals may be conceptualized and measured using an IPC framework consistent with adult assessments. Developmental and personality researchers alike suggest that this is an integral and necessary step before research can longitudinally test the question of whether these personality traits remain stable across developmental periods or which factors contribute to change in social goals across developmental transitions to adulthood (Shiner et al., 2002). Our findings suggest that the IGI-CR may be useful in measuring broad social goals in childhood and adolescence and has the added utility of synchronizing with adult measures such as the CSIV (Locke, 2000) allowing for the assessment of goal orientations across the life course. The IGI-CR may also help advance current models of social adjustment and help identify social goals that place youth at risk for problem behaviors (Markey, Markey, & Tinsley, 2005; Trucco, Bowker, & Colder, in press).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA019631) awarded to Craig R. Colder and the National Institute of Mental Health (F31MH087053) awarded to Aidan G.C. Wright. We thank the UB Adolescent and Family Development Project staff for their help with data collection, and all the families who participated in the study.

Footnotes

PCA was used to plot the individual items in component space. Plotting the items in this way allows for the evaluation of the relationship between each of the items. Items whose plotted location deviated from a priori placement based on the original IGI-C, were newly added, or whose communalities were low (i.e., < .10) were reevaluated for octant scale placement and retention based on item content, item to scale correlations, and internal consistency coefficients for target octants.

Contributor Information

Elisa M. Trucco, Department of Psychology, University at Buffalo, SUNY

Aidan G. C. Wright, Department of Psychology, The Pennsylvania State University

Craig R. Colder, Department of Psychology, University at Buffalo, SUNY

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Youth Self-Report for ages 11–18. Burlington, VT: ASEBA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Acton GS, Revelle W. Interpersonal personality measures show circumplex structure based on new psychometric criteria. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2002;79:456–481. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7903_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K. Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Browne M. Circumplex models for correlation matrices. Psychometrika. 1992;57:469–497. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research. 1992;21:230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1959;56:81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Asher SR. Children's goals and strategies in peer conflict situations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1996;42(1):125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Prakash K, O'Neil K, Armer M. Do you "want" to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(2):244–258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. Engagment in gender normative versus nonnormative forms of aggression: Links to social-psychological adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(4):610–617. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115(1):74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Madson L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122(1):5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis LK, Rothbart MK. Poster presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development. Minneapolis, MN: 2001. Apr, Revision of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Erdley CA, Asher SR. Children's social goals and self-efficacy perceptions as influences on their responses to ambiguous provocation. Child Development. 1996;67(4):1329–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar LR, Visser PS, Browne MW. Conceptual and methodological issues in testing the circumplex structure of data in personality and social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1997;1:184–203. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0103_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiological studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17(9):643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtman MB. Construct validity of interpersonal personality measures: The interpersonal circumplex as a nomological net. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtman MB, Pincus AL. Interpersonal Adjective Scales: Confirmation of circumplex structure from multiple perspectives. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtman MB, Pincus AL. The circumplex model: Methods and research applications. In: Velicer JSW, editor. Comprehensive handbook of psychology: Research methods in psychology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Wiley; 2003. pp. 407–428. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman L. A new approach to factor analysis: The radex. In: Lazarsfeld PF, editor. Mathematical thinking in the social sciences. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1954. pp. 258–348. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman L. Proceedings of the 1969 Invitational Conference on Testing Problems. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service; 1970. Integration of test design and analysis; pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hafkenscheid A, Rouckhout D. Circumplex structure of the Impact Message Inventory (IMI-C): An empirical test with the Dutch version. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91:187–194. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Wilson KR, Turan B, Zolotsev P, Constantino MJ, Henderson L. How interpersonal motives clarify the meaning of interpersonal behavior: A revised circumplex model. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:67–86. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert L, Arabie P. Evaluating order hypotheses within proximity matrices. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;102:172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvinen DW, Nicholls JG. Adolescents' social goals, beliefs about the causes of social success, and satisfaction in peer relations. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(3):435–441. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. PRELIS: A Preprocessor for Lisrel. Mooresville: Scientific Software, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J, Cadinu M, Poulin F, Bucci M. Group identification in early adolescence: Its relation with peer adjustment and its moderator effect on peer influence. Child Development. 2002;73(1):196–208. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Jones SM, Henrich CC, Hawley PH. Disentangling the "whys" from the "whats" of aggressive behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Dodge KA. Social-cognitive processes of severly violent, moderately aggressive, and nonaggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(2):366–374. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wayland KK, White KJ. Social goals: Relationship to adolescent adjustment and to social problem solving. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;12(3):135–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00911312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke KD. Circumplex scales of interpersonal values: Reliability, validity, and applicability to interpersonal problems and personality disorders. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2000;75:249–267. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7502_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey PM, Markey CN, Tinsley B. Applying the interpersonal circumplex to children's behavior: Parent-child interactions and behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:549–559. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najaka SS, Gottfredson DC, Wilson DB. A meta-analytic inquiry into the relationship between selected risk factors and problem behavior. Prevention Science. 2001;2(4):257–271. doi: 10.1023/a:1013610115351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen T, Grönroos M, Salmivalli C. An interpersonal circumplex model of children's social goals: Links with peer-reported behavior and sociometric status. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41(5):699–710. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL, Wright AGC. Interpersonal diagnosis of psychopathology. In: Horowitz L, Strack S, editors. Handbook of interpersonal psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 2010. pp. 359–381. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Cillessen AHN. Forms and functions of adolescent peer aggression associated with high levels of peer status. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49(3):310–342. [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill CM, Stoep AV, McCauley E, Katon WJ. Social competence and social support as mediators between comorbid depressive and conduct problems and functional outcomes in middle school children. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(2):535–553. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Krasnor L. The nature of social competence: A theoretical review. Social Development. 1997;6:111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Asher SR. Children's goals and strategies in response to conflicts within a friendship. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(1):69–79. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli C, Peets K. Pre-adolescents' peer relational schemas and social goals across relational contexts. Social Development. 2009;18(4):817–832. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, Caspi A. Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:2–32. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, Masten AS, Tellegen A. A developmental perspective on personality in emerging adulthood: Childhood antecedents and concurrent adaptation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(5):1165–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey T. RANDALL: A Microsoft FORTRAN program for a randomization test of hypothesized order relations. Education and Psychological Measurement. 1997;57:164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Bowker JC, Colder CR. Interpersonal goals and susceptibility to peer influence: Risk factors for intentions to initiate substance use during early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. doi: 10.1177/0272431610366252. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2005–2007. 2009 Jun; Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov.

- Verhulst FC, van der Ende J. Agreement between parents' reports and adolescents' self-reports of problem behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:1011–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS. A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:395–412. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS. Agency and communion as conceptual coordinates for the understanding and measurement of interpersonal behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Grove WM, editors. Thinking clearly about psychology: Essays in honor of Paul Meehl. Vol. 2. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1991. pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS, Phillips N, Trapnell P. Circular reasoning about interpersonal behavior: Evidence concerning some untested assumptions underlying diagnostic classification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56(2):296–305. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS, Steiger JH, Gaelick L. Evaluating circumplexity in personality data. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1981;16:263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Pincus AL, Conroy DE, Elliot AJ. The pathoplastic relationship between interpersonal problems and fear of failure. Journal of Personality. 2009;77:997–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Geiger TC, Crick NR. Relational and physical aggression, prosocial behavior, and peer relations: Gender moderation and bidirectional associations. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25(4):421–452. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.