Abstract

Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa L., syn. Cimicifuga racemosa L.) has become increasingly popular as a dietary supplement in the United States for the treatment of symptoms related to menopause, but the botanical authenticity of most products containing black cohosh has not been evaluated, nor is manufacturing highly regulated in the United States. In this study, 11 black cohosh products were analyzed for triterpene glycosides, phenolic constituents, and formononetin by high-performance liquid chromatography–photodiode array detection and a new selected ion monitoring liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry method. Three of the 11 products were found to contain the marker compound cimifugin and not cimiracemoside C, thereby indicating that these plants contain Asian Actaea instead of black cohosh. One product contained both black cohosh and an Asian Actaea species. For the products containing only black cohosh, there was significant product-to-product variability in the amounts of the selected triterpene glycosides and phenolic constituents, and as expected, no formononetin was detected.

Keywords: Black cohosh, dietary supplements, quality control, triterpene glycosides, phenolic constituents, formononetin, Actaea racemosa, Cimicifuga racemosa, Asian Actaea species

INTRODUCTION

Actaea racemosa L. (black cohosh) (syn. Cimicifuga racemosa L.), a plant native to eastern North America, has a long and diverse history of medicinal use. Black cohosh was traditionally used by Native Americans and early colonists to treat a variety of conditions including general malaise, malaria, rheumatism, abnormalities in kidney function, sore throat, and menstrual irregularities (1, 2). During the past 40 years, in North America and Europe, the roots and rhizomes of this plant have been used as an herbal medicine primarily for the treatment of symptoms related to menopause (3, 4). Considerable research on this plant has been reported, including phytochemical studies, bioassays, and at least seven placebo and/or treatment-controlled clinical trials (5-11).

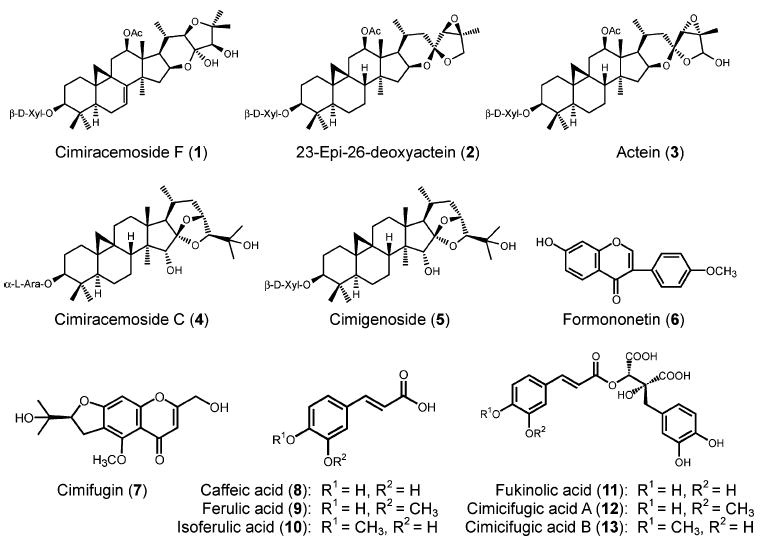

The major secondary compounds in black cohosh include triterpene glycosides and phenolics. Phytochemical research has led to the isolation of 42 triterpene glycosides from black cohosh since 1962, including cimiracemoside F (1), 23-epi-26-deoxyactein (2), previously known as 27-deoxyactein, and actein (3) (12-14). Because triterpene glycosides are the major secondary compounds of black cohosh, many commercial black cohosh products are standardized to triterpene glycosides, most often to 2 (Figure 1). Additional chemical research reported 15 polyphenolic constituents including caffeic acid (8), fukiic acid, piscidic acid, and their derivatives (15, 16) (Figure 1). In a single report, an isoflavone, formononetin (6), was described in black cohosh (17). This compound was not detected in black cohosh through a systematic study in our laboratory (18). A more recent report claimed to detect 6 in black cohosh (19), but additional work in our laboratory did not confirm this finding (20).

Figure 1.

Some of the triterpene glycosides and phenolic constituents reported from Actaea species.

A number of studies looked at the estrogenic potential of black cohosh. For example, in vivo studies found that black cohosh extracts increased uterine and ovary weight (21-23) and estrogen receptor α-expression (24) and reduced luteinizing hormone levels (23-26), pyridinoline/deoxypyridinoline levels, and bone loss (27). Some in vitro experiments with black cohosh extract have shown estrogenic activity (23-25). Other studies indicate that black cohosh does not have estrogenic activity (28-31). The phytoestrogen 6, which had been repeatedly cited to explain the estrogen-like effect of black cohosh in reducing hot flashes, has not been detected in our studies (18, 20). It is not known currently which constituents of black cohosh might be responsible for the reputed beneficial clinical effects on menopausal symptoms.

In the U.S. market, there are varieties of black cohosh products currently available directly to consumers in a range of formulations and dosages. Because black cohosh is still primarily wildcrafted in the United States, overharvesting is beginning to threaten its existence in the wild (32). Sourcing and authentication of black cohosh are a concern to manufacturers of dietary supplements. Some companies have begun to cultivate black cohosh in Europe (personal communication). Some Actaea species are cultivated in China and can be purchased at a lower cost than black cohosh. Thus, because of economic factors, the possibility exists that black cohosh products sold in the United States may be adulterated with less expensive Asian Actaea species (33). Reports that some herbal products contain potentially harmful adulterants, varying amounts of the advertised extract/components, or even incorrect plant species or plant parts have heightened these concerns (34-36), and reports suggest that adulterated black cohosh extracts are being found in American markets (33). Therefore, it is critical to examine the quality of the products commercially available.

Previous reports have indicated that certain marker compounds, such as cimiracemoside C (4) and cimifugin (7), can be used to distinguish black cohosh from other Actaea species (37). One study compared liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) chromatograms of several Asian Actaea species with black cohosh, but it is not easy to use these chromatograms routinely to distinguish Actaea species because they are complex (38). For the quality evaluation of the products, we developed a combined high-performance liquid chromatography–photodiode array detection (HPLC-PDA) and selected ion monitoring (SIM) LC-MS method that observes multiple ions in order to evaluate the quality of 11 black cohosh products. For those products containing black cohosh, the amounts of several selected triterpene glycosides and phenolic constituents were quantitatively analyzed and compared. In the botanical supplement industry and scientific research studies, different alcohols are used to extract black cohosh, and there is insufficient information on whether, or the degree to which, this may impact biological activity. To compare differences in the chemical constituents due to extraction techniques, 80% methanolic, 75% ethanolic, and 40% 2-propanolic extracts of the dried roots and rhizomes of black cohosh were prepared to replicate the extraction techniques of commercial black cohosh products or for laboratory research. The phenolic and triterpenoid glycoside profiles of our three alcohol extracts were examined by using the HPLC-PDA and LC-MS methods. All 11 black cohosh products were also examined for 6 by a combination of thin-layer chromatography (TLC), HPLC, and LC-MS methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Reagents

HPLC grade acetonitrile (J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ), chloroform (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Aldrich) were used for sample preparation and HPLC analysis. Reagent grade methanol (E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), formic acid (E. Merck), and sodium hydroxide (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) were used in our study. The absorbents for open column chromatography were octadecyl (C18 40 μm) (J. T. Baker) and Diaion HP-20 (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA).

Black Cohosh Products

The black cohosh products were obtained from 2002 to 2004, primarily from stores in the metropolitan New York City area. Seven products were capsules, and four were tablets. Most products were manufactured from black cohosh extracts except the product C-4, which contained powdered plant material. Detailed information about all products is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Information Based on the Label Claims of the 11 Black Cohosh Products

| product | form | stated extract in each tablet/capsule (mg) | extract standardized by 23-epi-26-deoxyactein (%) | amount of triterpene glycosides per tablet/capsule (mg) | direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | capsule | 40 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 1 capsule/day |

| C-2 | capsule | 50 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 1 capsule/day |

| C-3 | capsule | 40 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 2 capsules/day |

| C-4 | capsule | 370 (rhizome and root) | 0.75–1.25 | 3.70 in 370 mg of material | 1–3 capsules/day |

| C-5 | capsule | 545 | 0.2 | 1.00 | 1–4 capsules/day |

| C-6 | capsule | 40 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 2 capsules/day |

| C-7 | capsule | 40 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 2 capsules/day |

| T-1 | tablet | 20 | not stated | not stated | 2 tablets/day |

| T-2 | tablet | 40 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 2 tablets/day |

| T-3 | tablet | 200 | 2.5 | 5.00 | 1 tablet/day |

| T-4 | tablet | 32.5 | not stated | not stated | 1 tablet/day |

Standards and Controls

Compounds 1 (86.39% purity), 2 (60.74% purity), and 7 were purchased from ChromaDex (Santa Ana, CA). Compound 8 and ferulic acid (9) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Isoferulic acid (10) (97.37% purity), fukinolic acid (11) (95.98% purity), cimicifugic acid A (12) (90.07% purity), and cimicifugic acid B (13) (79.53% purity) were isolated from black cohosh extract by the following procedures. A dried ethanolic extract of black cohosh (500 g, PureWorld Botanicals, Inc., South Hackensack, NJ) was re-exacted with 80% MeOH/water (2 L) at room temperature for 12 h. After the MeOH was removed in vacuo, the resulting aqueous solution was partitioned with hexane (2 L) and n-butanol (3 L) successively. A portion of the resulting n-butanol extract (30 g) was further separated over Diaion HP-20 (600 g) eluting with MeOH/H2O (1:1 v/v, 4 L) to give four fractions. From fraction II (1.03 g), 10 (284.2 mg) was obtained as crystals. The water solution was separated over Diaion HP-20 (600 g) eluting with MeOH/H2O (1:1 v/v, 5 L) to give five fractions (I–V). Fraction II (300.0 mg) was further separated by C18 column chromatography eluting with 0.1% acetic acid/MeCN gradient solvent system (95:5–80:20 v/v, 5% steps) to yield a total of 16 subfractions. Compound 11 (42.6 mg) was obtained from subfraction 9 while 12 (8.1 mg) was obtained from subfraction 13. Subfraction 16 was further separated by preparative C18 HPLC eluting with an isocratic solvent system 0.1% acetic acid/MeCN (80:20 v/v), and 13 (2.8 mg) was obtained. The purities of 10–13 were determined by HPLC-PDA at 320 nm. Compound 6 (purity >99% by TLC) was purchased from Fluka Chemie (CH-9470, Buchs, Switzerland).

Sample Preparation for Analysis of Triterpene Glycosides

To partially purify the samples before HPLC-PDA analysis, a previously published solvent–solvent partitioning scheme was employed for each black cohosh product/extract to obtain fractions enriched in triterpene glycosides (37). The amounts of the black cohosh product used in this study were shown as follows [product code/number of capsules or tablets/weight (g)]: C-1/10/5.62, C-2/16/3.61, C-3/10/1.86, C-4/10/3.71, C-5/10/5.54, C-6/8/2.02, C-7/12/5.43, T-1/15/4.17, T-2/12/2.99, T-3/ 6/4.80, and T-4/8/2.08. For the three alcoholic extracts of black cohosh, 0.40 g of each extract was used for the analysis of triterpene glycosides. Samples were prepared as follows: a composite of capsules/tablets/extracts was dissolved in 50 mL of 0.5% NaOH water solution. The solution was sonicated for 60 min, then transferred into a separatory funnel, and extracted with chloroform (50 mL) by shaking vigorously for 2 min. The mixture was centrifuged for 20 min at 3000 rpm. After the chloroform solution was removed, the NaOH aqueous solution was extracted three more times using 50 mL of chloroform each time. All chloroform solutions were combined and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was dissolved in 10 mL of DMSO and filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane. The filtered sample was then analyzed for triterpene glycosides by HPLC and LC-MS.

Sample Preparation for Analysis of Phenolics

Black cohosh products (0.3–1.2 g) were dissolved in 10 mL of 70%MeOH/H2O solution (25 mL for C-7). For the alcoholic extracts of black cohosh, the sample (7–9 mg) was dissolved with 2 mL of 70% MeOH/H2O solution, sonicated for 10 min, and passed through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane filter. The amounts of the black cohosh products/extracts used for the analysis of phenolics are shown below [product code/number of capsules or tablets/weight (g)]: C-1/2/1.02, C-2/2/0.45, C-3/2/0.34, C-4/2/0.73, C-5/2/1.08, C-6/2/0.53, C-7/5/2.28, T-1/4/1.12, T-2/2/0.49, T-3/1/0.79, T-4/2/0.52, 80% methanolic extract/7.5 mg, 75% ethanolic extract/9.0 mg, and 40% 2-propanolic extract/7.9 mg.

Compound 6

Sample preparation for the analysis of 6 was the same as the method used to prepare samples for the analysis of phenolics mentioned above. When a sample was found to display a peak with a similar retention time to 6 by HPLC-PDA, the sample was prepared again by the following method.

The contents of two tablets/capsules of the black cohosh product were dissolved in MeOH (5–10 mL). The solution was sonicated for 5 min and then filtered. The residue was repeatedly extracted with MeOH again using the same method. The filtrates were combined and evaporated to yield a residue that was dissolved in 0.5 mL of MeOH. The MeOH solution was further separated by preparative silica gel 60 F254 TLC on 10 cm × 10 cm, 250 μm plates. The mobile phase was ethyl acetate:toluene:glacial acetic acid (17.5:80:2.5). The plates were visualized under UV light at 254 nm. Co-TLC with the standard 6, the silica gel within the range of the Rf-formononetin ± 0.5 cm was scraped, collected, and extracted with MeOH (5 mL). The MeOH solution was evaporated, and the residue was redissolved in MeOH (0.2 mL) and analyzed by HPLC-PDA.

Alcoholic Extracts from Black Cohosh Plant Material

Ground black cohosh plant material (10 g) was extracted with 100 mL of 80% methanol at ambient temperature for 12 h and then filtered. The resulting plant material was extracted repeatedly three more times using the same solvent, each time for 12 h. The filtrates were combined and evaporated in vacuo to give a dark brown extract (1.50 g). Ethanolic (75%) and 2-propanolic (40%) extracts of black cohosh plant material were also prepared using the same extraction method, and 1.68 and 2.25 g of the extracts were obtained, respectively.

Asian Actaea Species

Three Asian Actaea species, Actaea cimicifuga L., Actaea dahurica Turcz. ex Fisch. and C. A. Mey., and Actaea yunnanensis (P. G. Xiao) J. Compton (39), were collected from Yunnan and Hebei provinces (P. R. China) in 2002–2005. The plant materials were identified by Professors Ming-Hua Qiu and Zong-Yu Wang, researchers in the Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The vouchers are deposited in Kunming Institute of Botany with the identification numbers K20030615 (A. cimicifuga), K20020082 (A. dahurica), and K20050825 (A. yunnanensis). Roots and rhizomes of A. cimicifuga (0.37 g), A. dahurica (0.43 g), and A. yunnanensis (0.38 g) were powdered and extracted with 5 mL of 70% methanol at ambient temperature, sonicated for 10 min, and then passed through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane filter.

Identification and Quantitation of Triterpene Glycosides and Phenolics

The samples and standards were analyzed using HPLC with a Waters 2695 separations module (Milford, MA) equipped with a 996 PDA and operated with Empower software. Separations were carried out on a 150 mm × 3.9 mm i.d., 5 μm, Waters C18 column for the triterpene glycosides, and a 250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 μm, Phenomenex Aqua C18 column for the phenolics and 6 at ambient temperature with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The sample volume injected was 10 μL, and data were analyzed at 203 nm for triterpene glycosides, 320 nm for phenolic compounds, and 258 nm for 6. The mobile phase for the analysis of triterpene glycosides consisted of a step gradient starting with 5% (v/v) acetonitrile (solvent A) in water (B) and increasing to 75% A over 55 min. The gradient profile was as follows: 0–18 min, 5–28% A; 18–36 min, 28–35% A; 36–45 min, 35–55% A; and 45–55 min, 55–75% A. The solvent system for the analysis of the phenolic constituents and 6 was composed of acetonitrile (A) and 10% aqueous formic acid (B) using a step gradient elution of 5–15% A at 0–15 min, 15% A at 15–20 min, 15–50% A at 20–50 min, and 50–100% A at 50–55 min. The UV/vis spectra were recorded from 200 to 500 nm. Preparative HPLC was carried out using a Waters 600 controller with a Waters 486 tunable absorbance detector and Waters Empower software with a 250 mm × 21.1 mm i.d., 10 μm, Phenomenex Nucleosil C18 column and an isocratic solvent system of 0.1% acetic acid/MeCN (80:20 v/v), a flow rate of 5 mL/min, column at room temperature, and 60 min run time.

Mass spectra were recorded on a LCQ Mass Spectrometer (Thermo-Finnigan, San Jose, CA) equipped with an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) source. APCI was performed to analyze triterpene glycosides with the discharge current at 5 μA. The vaporizer and capillary temperatures were set to 450 and 150 °C, respectively. The sheath gas and auxiliary gas, both nitrogen, had flow rates of 80 and 10 units, respectively. A mass range of 50–1000 amu was scanned.

Validation of Analytical Method

The quantitative HPLC method was validated with respect to linearity, recovery, and sensitivity. Eight stock solutions containing about 1 mg/mL of standards 1, 2, and 8–13, respectively, were prepared independently in DMSO (for compounds 1 and 2) and 70% MeOH/water (for compounds 8–13). For calibration purposes, working solutions were freshly prepared by diluting each stock solution with DMSO or 70% MeOH/water. Calibration curves were established on five data points covering the concentration 50–900 (for compounds 1 and 2) and 1–400 μg/mL (for compounds 8–13). Each calibration curve was obtained by plotting the peak area vs the concentration of the standard. Limits of detection were determined by analysis of the peak height vs the baseline noise at a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1. Reliabilities of the extraction methods were assessed by mixing marker compounds (2–4 mg for phenolics 8–13 and 0.8–1.2 mg for triterpene glycosides 1 and 2) in the powdered material of the three selected products, C-4, C-7, and T-2, and the recovery of the marker compounds was determined.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Methods Development

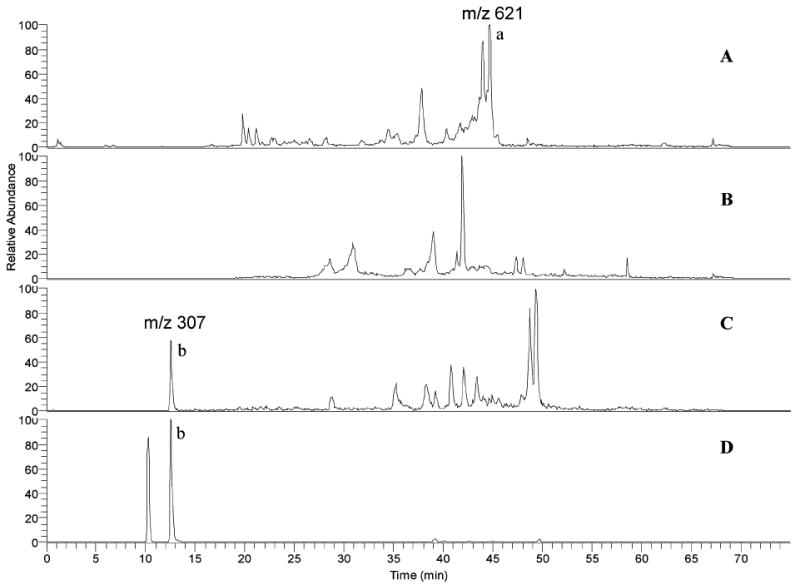

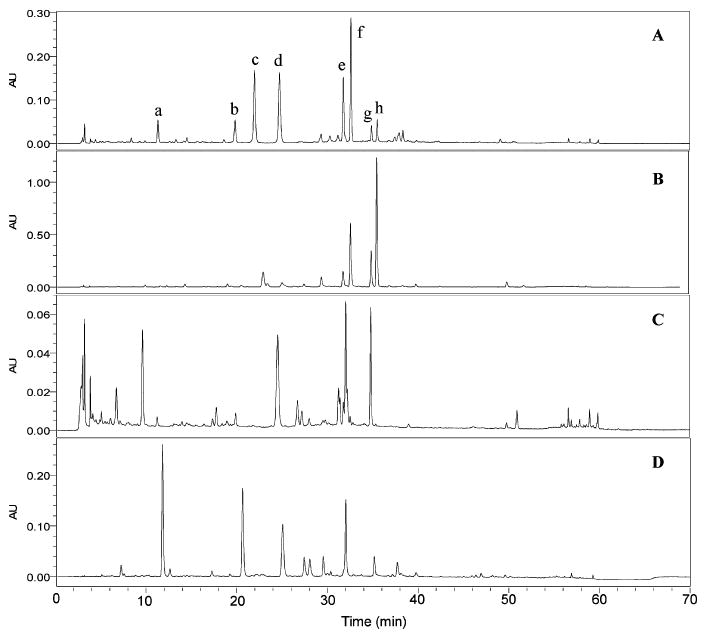

It has been reported that 4 and 7 can be used as chemical markers for Actaea species identification, because 4 is only found in black cohosh while 7 is found in some Asian species of Actaea but not in black cohosh (37). We, therefore, developed a positive APCI SIM LC-MS technique simultaneously scanning for these three ions (m/z 307, 469, and 621) to generate a chromatogram for the identification of black cohosh. We have used this method to analyze three Asian Actaea species and found that black cohosh displays a unique chromatogram (Figure 2). We also found that black cohosh shows a HPLC-PDA chromatogram (at 320 nm) for the phenolic constituents significantly different from Asian Actaea species (Figure 3), and thus, the HPLC-PDA chromatogram can be used for the species distinction. We concluded that this combined SIM LC-MS and HPLC-PDA method can be used to identify black cohosh extracts and products. We have examined the limit of detection (LOD) of this combined analytical method and found that when black cohosh in the plant mixture of Actaea species is higher than 5%, it can be clearly detected. When black cohosh is present in a plant mixture of Actaea species less than 75%, the other Actaea species can be detected in the mixture.

Figure 2.

SIM LC-MS chromatograms of black cohosh and three Asian Actaea species: (A) A. racemosa, (B) A. dahurica, (C) A. cimicifuga, and (D) A. yunnanensis. Peaks: a, 4; b, 7.

Figure 3.

HPLC-PDA chromatograms for the phenolic constituents of black cohosh and several Actaea species (320 nm): (A) A. racemosa, (B) A. dahurica, (C) A. cimicifuga, and (D) A. yunnanensis. Peaks: a, 8; b, 9; c, 10; d, 11; e, 12; f, 13; and g and h, cimicifugic acids E and F.

Qualitative Analysis

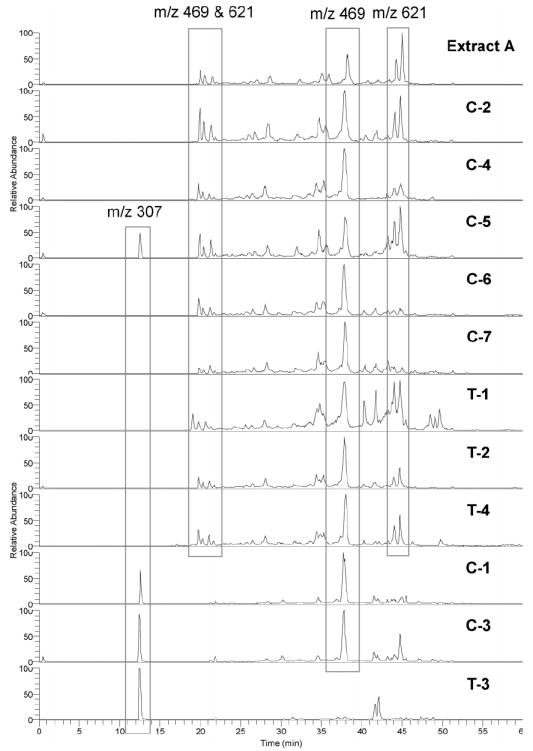

All 11 products and the 80% methanolic extract of black cohosh were analyzed using the combined SIM LC-MS and HPLC-PDA technique. On the basis of the SIM LC-MS analysis, eight of the products were determined to be made from black cohosh because they displayed the same chromatograms as black cohosh extract, and 4 was observed from these eight products. Products C-1, C-3, and T-3 displayed chromatograms that were very different from black cohosh extract. Compound 4 (m/z 621 [M + H]+) was not detected in C-1, C-3, and T-3; 7 (m/z 307 [M + H]+) was found in these three products, as well as the product C-5, suggesting that these three products were made using Asian Actaea species (Figure 4). Concerning product C-5, although 7 was found, C-5 has the expected chemical profile for black cohosh, thereby indicating that this product contained both black cohosh and Asian Actaea plant material (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

LC-MS SIM scan at m/z 307 for 7, 469 for cimifugin glycoside, and 621 for 4. Extract A, 80% MeOH black cohosh extract.

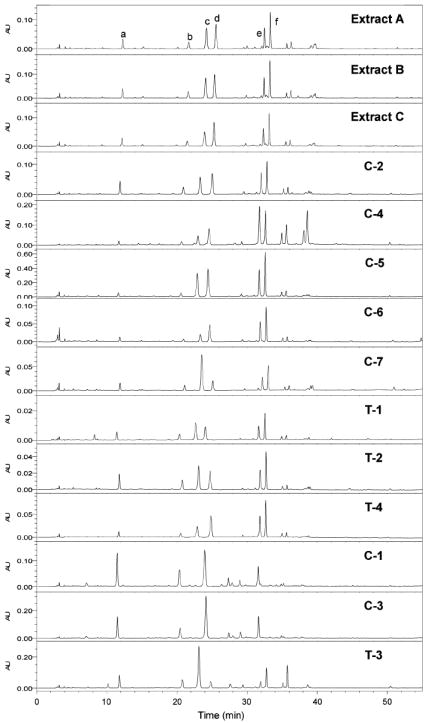

Results from the analysis of the phenolic constituents of the 11 black cohosh products by HPLC-PDA method also supported the above conclusion. Most products displayed chemical profiles of phenolic constituents similar with black cohosh except for the products C-1, C-3, and T-3 (Figure 5), indicating that they were different from common black cohosh products.

Figure 5.

HPLC-PDA chromatograms for phenolic constituents in three black cohosh alcoholic extracts and 11 black cohosh products (320 nm). Extracts: A, 80% MeOH; B, 75% EtOH; and C, 40% 2-propanol. Products: C-1 to C-7, black cohosh capsules; T-1 to T-4, black cohosh tablets. Peaks: a, 8; b, 9; c, 10; d, 11; e, 12; and f, 13.

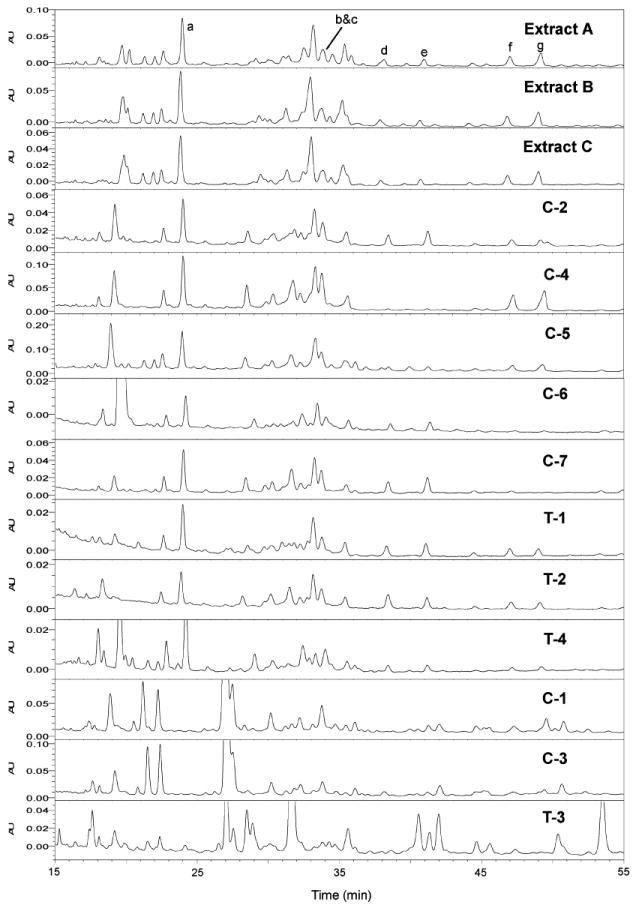

Quantitative Analysis of Triterpene Glycosides

The 11 products, as well as the three alcoholic extracts prepared from black cohosh roots and rhizomes, were analyzed for the triterpene glycosides using HPLC-PDA and LC-MS methods. The resulting chromatograms for the triterpene glycosides are shown in Figures 6 and 7.

Figure 6.

HPLC-PDA chromatograms for triterpene glycosides in three black cohosh alcoholic extracts and 11 black cohosh products (203 nm). Extracts: A, 80% MeOH; B, 75% EtOH; and C, 40% 2-propanol. Products: C-1 to C-7, black cohosh capsules; T-1 to T-4, black cohosh tablets. Peaks: a, 1; b, 2; c, 3; d, unknown; e, unknown; f, 4; and g, 5.

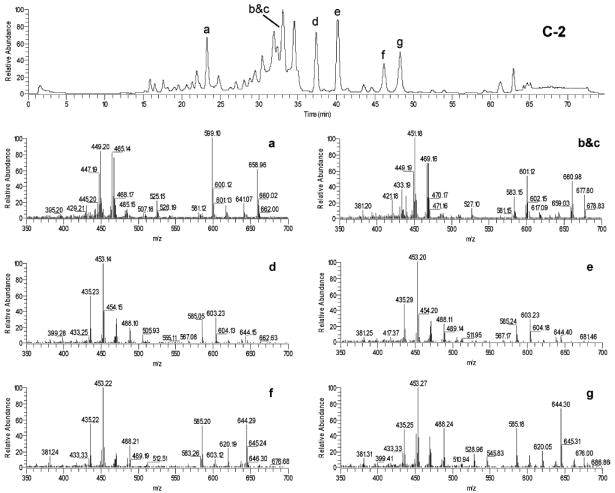

Figure 7.

LC-MS APCI-TIC spectrum and mass spectra for seven triterpene glycosides from the black cohosh product C-2. Peaks: a, 1; b, 2; c, 3; d, unknown; e, unknown; f, 4; and g, 5.

Seven of the major triterpene glycosides were selected for the quantitative analysis. According to the LC-MS analysis, these compounds were identified as 1–3, unknown triterpene glycoside, unknown triterpene glycoside, 4, and cimigenoside (5) due to the characteristic fragments in the LC-MS spectra (Figure 7) (37). The reason for selecting these seven triterpene glycosides was that they were major triterpene glycosides in the black cohosh extract according to LC-MS analysis, and most of them were baseline separated in HPLC-PDA and LC-MS chromatograms, making them suitable for quantitative analysis. Although 2 and 3 overlap with each other in our study by a spiking experiment, they were still chosen for the quantitative analysis because of the importance of 2 for standardization in most commercial products. The amounts of the seven triterpene glycosides in the 11 products and three alcohol extracts of black cohosh are shown in Table 2. Because of the different UV absorption, due to a double bond in the structure, the amount of 1 was calculated based on the commercial standard 1, and the amounts for other six triterpene glycosides were all calculated using the commercial standard 2.

Table 2.

Amounts (mg) of the Seven Triterpene Glycosides in Each Tablet/Capsule or Black Cohosh Extract

| product | compound |

total | % in exta | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 and 3 | unknown | unknown | 4 | 5 | |||

| C-1 | 1.44 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.75 | 3.02 | 7.55 | ||

| C-2 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 1.50 | 3.00 |

| C-3 | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 1.82 | 4.55 | ||

| C-4 | 0.60 | 2.23 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.11 | 1.65 | 5.69 | 4.74 |

| C-5 | 0.92 | 2.13 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 5.75 | 1.06 |

| C-6 | 0.36 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.94 | 2.34 |

| C-7 | 0.21 | 0.57 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 1.58 | 3.95 | ||

| T-1 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.66 |

| T-2 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.63 | 1.58 |

| T-3 | 0.71 | overlap | 0.71 | 0.36 | ||||

| T-4 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.70 |

| 80% MeOH | 5.58 | 12.62 | 4.20 | 4.18 | 6.39 | 8.41 | 41.37 | 10.34 |

| 75% EtOH | 5.27 | 12.95 | 2.97 | 3.27 | 5.88 | 8.14 | 38.49 | 9.61 |

| 40% 2-propanol | 3.80 | 9.19 | 2.43 | 2.35 | 4.23 | 5.77 | 27.77 | 6.94 |

The amount of black cohosh extract in each capsule/tablet was based on the label claim.

There was significant product-to-product variability in the amounts of triterpene glycosides measured. For the eight products containing black cohosh, the total amount of the seven selected triterpene glycosides in each capsule/tablet varied 44-fold (0.1311–5.7527 mg). On the basis of the label claim for the amount of the black cohosh extract in each capsule/tablet (Table 1), the total amount of the seven selected triterpene glycosides was further calculated as the proportion of the triterpene glycosides in the black cohosh extract. The proportions also varied 7-fold (0.66–4.74%) among the eight black cohosh products, indicating significant differences among the black cohosh extracts that were used to produce the 11 black cohosh products. Because information is not given on each label about which and how many triterpene glycosides were used for the quantitative analysis for each product, it is impossible to compare our results with label claims.

Quantitative Analysis of Phenolics

There were six major phenolic constituents in the HPLC-PDA chromatograms for all products containing black cohosh (Figure 5). On the basis of the spectroscopic analysis by HPLC-PDA, the six major phenolic compounds were identified as 8–13.

As shown in Table 3, there are significant differences in the amounts of phenolic constituents among the products made from black cohosh. The total amount of six major phenolic compounds in each capsule/tablet varied 64-fold (0.09267–5.9399 mg). On the basis of the amount of the black cohosh extract in each capsule/tablet according to the label claim (Table 1), the proportions of the six selected phenolic compounds in the extracts varied 5-fold (0.46–2.23%) among the eight black cohosh products.

Table 3.

Amounts (mg) of the Six Phenolic Constituents in Each Tablet/Capsule or Black Cohosh Extract

| product | compound |

total | % in exta | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |||

| C-1 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 1.40 | 3.50 |

| C-2 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 1.11 | 2.23 |

| C-3 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 1.72 | 0.66 | 0.01 | 2.64 | 6.59 |

| C-4 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 2.02 | 1.68 |

| C-5 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.54 | 2.14 | 1.54 | 1.59 | 5.94 | 1.09 |

| C-6 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 1.24 |

| C-7 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.44 | 1.09 |

| T-1 | trb | tr | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| T-2 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.44 | 1.09 |

| T-3 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.90 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.69 | 2.73 | 1.36 |

| T-4 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.38 | 1.17 |

| 80% MeOH | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 5.82 |

| 75% EtOH | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.52 | 5.78 |

| 40% 2-propanol | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.40 | 5.15 |

The amount of black cohosh extract in each capsule/tablet was based on the label claim.

tr, trace (<0.005 mg).

Analysis of 6

According to the HPLC-PDA chromatograms at 258 nm, eight of the 11 black cohosh products did not display any peaks between 45 and 46 min where 6 would appear, while products C-1 and C-3 revealed two minor peaks at this region but the peaks were determined not to be 6 based on differences in UV absorptions and an HPLC spiking experiment. Product T-4 displayed a minor peak, which had the same retention time as 6 in the HPLC-PDA chromatogram. Therefore, a detailed examination of T-4 was performed by a combined preparative TLC and HPLC experiments, but 6 was not identified in this sample.

Validation of HPLC Method

The HPLC-PDA method was validated with respect to linearity, recovery, and sensitivity. Linear regression analysis for each standard was performed by the external standard method. Good linearity (r2 > 0.999) of five-point calibration curves was obtained for all standards between peak area and concentration over the range test (ca. 1–400 μg/mL for phenolic constituents and 50–900 μg/mL for triterpene glycosides). On the basis of the HPLC-PDA experiments, LODs were determined to be from 0.11 to 0.38 μg for the triterpene glycosides and from 1.25 to 5.03 ng for the phenolic constituents. The LOD of 6 was 0.6 ng. The recovery of triterpene glycosides was determined to be 95.80% while the recovery of the phenolic constituents was between 98.54 and 102.34% based on spiking experiments. The LOD of 7 was determined to be 1.3 ng by HPLC-PDA and 0.3 ng by LC-MS.

Black cohosh and other Actaea species are rich in triterpene glycosides and polyphenolic constituents. When full scan mode LC-MS is used for the analysis, there are many peaks in the resulting chromatograms, including many similar peaks because black cohosh and other Actaea species have some similar constituents (38). This increases the difficulty of distinguishing black cohosh from other Actaea species, especially when black cohosh coexists with other constituents or excipients. The SIM LC-MS method developed in this study only examines several selected constituents; therefore, the chromatograms are very clean and easily identified.

Asian Actaea Species

The most notable finding of this study is the presence of 7 and the absence of 4 in four of the 11 products tested, suggesting that these four products contained Asian Actaea species. Several Asian Actaea species, including A. cimicifuga (syn. Cimicifuga foetida), A. dahurica, and A. heracleifolia, are interchangeably called “shengma” (40). As a well-known traditional Chinese medicine, shengma is widely cultivated and used for the treatment of a variety of diseases in China. Although shengma species contain some constituents similar to black cohosh, such as 2 and some similar phenolics, the chemical profiles for both triterpene glycosides and phenolic constituents are different from those of black cohosh (38). The medical uses of shengma are also different from those of black cohosh (40, 41). Therefore, the health consequences of interchanging black cohosh with shengma are not known.

With the increasing demands for black cohosh plant material for the production of menopausal dietary supplements in the United States, the adulteration of black cohosh, especially with Asian Actaea species, may increase further. The fact that more than one-third of black cohosh products analyzed in this study probably contain Asian Actaea species indicates that black cohosh products commercially available in the United States may not be as claimed. Not only may products containing A. racemosa have different amounts of the extract or key constituents but a newer problem of adulteration with extracts from less expensive Asian species seems to be emerging. Effective enforcement and improvement of regulatory requirements for the quality control of these products is necessary. We have little information on safety profiles of Asian Actaea species, but their clinical use in China differs from that of black cohosh in the United States.

Quantitative Comparison

To exemplify the differences among the black cohosh products, two of the capsules (C-2 and C-4) and two of the tablets (T-1 and T-2) were chosen for comparison of the major constituents. The label recommends doses of 1 capsule/day for the products C-2 and C-4 (Table 1) and 2 tablets/day for the products T-1 and T-2. However, according to our experiments, the amount of the seven selected triterpene glycosides in each capsule of product C-4 is 3.8 times as large as that in the product C-2. The amount of six major phenolic constituents in each capsule of product C-4 is 1.8 times that in the product C-2. The amounts of triterpene glycosides and phenolic constituents of the product T-2 are 4.8 and 4.7 times those of the product T-1 in each tablet, respectively. The effect of taking these significantly different amounts of triterpene glycosides and phenolic constituents is not known, particularly since we do not know whether these are the physiologically relevant compounds for menopausal symptoms. Further research is necessary.

According to the label claims, the proportion of triterpene glycosides for most products is declared to be 2.5% (w/w) of the black cohosh rhizomes and root extract, and each capsule/tablet is stated to contain about 1 mg of triterpene glycosides (or 40–50 mg of extract). However, we found that the total amount of the selected triterpene glycosides that we analyzed among most of the 11 black cohosh products was different from these label claims, suggesting that manufacturers of the products may have different methods of standardizing the extracts.

Compound 2

According to the label claims, most products were standardized to 2. However, because 2 can be found in many Actaea species other than A. racemosa, it is not an appropriate choice as a sole marker of identity. We detected 2 in all 11 products although three of them probably contain Asian Actaea species, suggesting that some manufacturers may only be using 2 to verify the identity of their plant material/extract.

Ratios of Phenolics and Triterpene Glycosides

We investigated the total proportions of the seven triterpene glycosides and the six phenolic constituents in our methanolic, ethanolic, and 2-propanolic extracts of black cohosh roots and rhizomes by an HPLC-PDA method. The total proportions in the three alcoholic extracts ranged from 6.9 to 10.3% for the triterpene glycosides and from 5.2 to 5.8% for the phenolic constituents. However, the same proportions in most black cohosh products were from 1.1 to 4.7% for the seven triterpene glycosides and from 1.1 to 3.5% for the six phenolics. Because large-scale industrial methods of extracting plants are often not as effective as small-scale extractions typically done in research laboratories, it is reasonable that the proportions of the two kinds of constituents would be lower in the large-scale industrial extraction than that in the small-scale laboratory extraction. If the ratio of triterpene glycosides to phenolics in the black cohosh extract can be regarded as approximately 1–2:1, only products C-4 and C-7 failed to meet this ratio among the seven products containing only black cohosh. This indicates that most of the seven black cohosh products contain extracts similar to our alcoholic extract of black cohosh, but the efficiency of the extraction techniques employed differed from product to product. The amounts of both triterpene glycosides and phenolics in the black cohosh extracts of the products were much lower than those in the black cohosh extracts obtained in our small-scale extraction.

Concerning products C-4 and C-7, the significantly different ratios of the triterpene glycosides to phenolics of those two products may be caused by the different extraction solvents employed. According to our experiments, when black cohosh is extracted by methanol/water solution, the ratio of triterpene glycosides to phenolics in the extract depended upon the proportion of methanol in the solution. For example, when the proportion of methanol is 100, 80, 60, and 0%, the ratio of triterpene glycosides to phenolics is 4.3, 1.8, 1.3, and 0.6, respectively.

Difference between Capsule and Tablet

We found that black cohosh capsules seem to contain higher amounts of triterpene glycosides than the tablets. If the amount of black cohosh extract in each capsule/tablet were normalized to 40 mg, the amounts of triterpene glycosides in each capsule would range from 0.42 to 1.58 mg in the five capsules while the amounts of triterpene glycosides in each tablet would only be from 0.26 to 0.63 mg in the three tablets. Perhaps specific formulation techniques are used to produce these tablets, to facilitate their release in acidic conditions, such as in the stomach. Therefore, T-1 was mixed with a small amount of 1.0 M HCl at 37 °C for 30 min and then extracted with 80% methanol/water solution. However, according to HPLC-PDA analysis, the amount of the seven selected triterpene glycosides was similar to that of the sample without processing with strong acid. The reason that T-1 black cohosh tablets display much lower amounts of triterpene glycosides is not known.

Stability Testing

To understand whether the major constituents of black cohosh in products are stable or not, we have tested the stabilities of the two classes of constituents in one black cohosh product during the past 30 months. We selected 10 constituents including triterpene glycosides and phenolics and analyzed the amounts of those selected compounds every 6 months. No constituents changed qualitatively and quantitatively, suggesting the stability of the major constituents of black cohosh in the products (results not shown). Therefore, the fact that there are significant differences among the amounts of major constituents of the eight black cohosh products is likely due to differences in manufacturing processes or plant material, rather than the instability of the constituents in black cohosh.

Commercially available black cohosh products in the United States are produced from black cohosh extracted with different alcohols. For example, one popular black cohosh product is an 40% 2-propanolic extract, while some other products are 58–75% ethanolic extracts (10). There is some suggestion that differences in biological activities might be a function of different extraction methods (30). For example, a black cohosh methanol extract was compared to a 40% 2-propanol extract and a 75% ethanol extract, and the methanol extract showed the greatest inhibition of binding for the human serotonin receptor 5-HT7 subtype (30).

To understand why different alcoholic black cohosh extracts show different biological activities, we analyzed and compared the triterpene glycosides and phenolic constituents in the 100% methanolic, 80% methanolic, 75% ethanolic, and 40% 2-propanolic black cohosh extracts. We found that the four extracts had similar chemical profiles for the major phenolic constituents, but the relative amounts and ratios of some of the major triterpene glycosides in the methanolic extract were significantly different from those in the other extracts (results not shown). Therefore, different chemical profiles, different proportions of the major constituents, and even different ratios of some constituents in the black cohosh extracts all may result in different bioactivities. The fact that the eight black cohosh products in this study have different proportions and contents of the major constituents suggests the possibility that the products could have different biological activities.

A method is required to standardize and evaluate the quality of the black cohosh products. This is also an urgent priority to conduct the basic science and clinical studies to evaluate efficacy and mechanism of action and to accurately access safety and adverse events claims.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study has been carried out with financial support from the Edith C. Blum Foundation and from the National Institutes of HealthsNational Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NIH-NCCAM) (Grants P50-AT00090 and R21 AT002930). The content of this paper is solely our responsibility and does not necessarily reflect the official views of NIH-NCCAM.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Table of HPLC-PDA calibration curves and limits of detection of the eight standards and LC-MS APCI-TIC spectra of the triterpene glycosides of the 11 black cohosh products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Barton BS. Collections for an Essay Towards a Material Medica of the United States. Way & Groff; Philadelphia: 1798. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rafinesque CS. Medical Flora or Manual of the Medical Botany of the United States of North America. Atkinson & Alexander; Philadelphia: 1828. p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrelli F, Izzo AA, Ernst E. Pharmacological effects of Cimicifuga racemosa. Life Sci. 2003;73:1215–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronenberg F, Fugh-Berman A. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for menopausal symptoms: A review of randomized control trails. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:805–813. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnecke G. Beeinflussung klimakterischer beschwerden durch ein phytotherapeutikum: Erfolgreiche therapie mit Cimicifuga-monoextrakt. Med Welt. 1985;36:871–874. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoll W. Phytotherapy influences atrophic vaginal epithelium: Double-blind study–Cimicifuga vs estrogenic substances. Therapeuticum. 1987;1:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehmann-Willenbrock E, Riedel HH. Clinical and endocrinologic studies of the treatment of ovarian insufficiency manifestations following hysterectomy with intact adnexa. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1988;110:611–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson JS, Troxel AB, Evans J, Klaus L, Vahdat L, Kinne D, Lo KM, Moore A, Rosenman PJ, Kaufman EL, Neugut AI, Grann VR. Randomized trial of black cohosh for the treatment of hot flashes among women with a history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2739–2745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liske E, Hanggi W, Henneicke-von Zepelin HH, Boblitz N, Wustenberg P, Rahlfs VW. Physiological investigation of a unique extract of black cohosh (Cimicifugae racemosae rhizoma): A 6-month clinical study demonstrates no systemic estrogenic effect. J Women’s Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:163–174. doi: 10.1089/152460902753645308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wuttke W, Seidlova-Wuttke D, Gorkow C. The Cimicifuga preparation BNO 1055 vs conjugated estrogens in a double-blind placebo-controlled study: Effects on menopause symptoms and bone markers. Maturitas. 2003;44(Suppl. 1):S67–S67. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(02)00350-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pockaj BA, Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Novotny PJ, Barton DL, Hagenmaier A, Zhang H, Lambert GH, Reeser KA, Wisbey JA. Pilot evaluation of black cohosh for the treatment of hot flashes in women. Cancer InVest. 2004;22:515–521. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200026394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen SN, Li WK, Fabricant DS, Santarsiero BD, Mesecar A, Fitzloff JF, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR. Isolation, structure elucidation, and absolute configuration of 26-deoxyactein from Cimicifuga racemosa and clarification of nomenclature associated with 27-deoxyactein. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:601–605. doi: 10.1021/np010494t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panizzi L, Corsano S, Actein I. Atti Accad Naz Lincei, Rend, Cl Sci Fis, Mat Nat. Vol. 32. 1962. pp. 601–605. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao Y, Harris A, Wang M, Zhang H, Cordell GA, Bowman M, Lemmo E. Triterpene glycosides from Cimicifuga racemosa. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:905–910. doi: 10.1021/np000047y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burdette JE, Chen SN, Lu ZZ, Xu H, White BE, Fabricant DS, Liu J, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR, Constantinou AI, Van Breemen RB, Pezzuto JM, Bolton JL. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa L.) protects against menadione-induced DNA damage through scavenging of reactive oxygen species: Bioassay-directed isolation and characterization of active principles. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:7022–7028. doi: 10.1021/jf020725h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen SN, Fabricant DS, Lu ZZ, Zhang HJ, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR. Cimiracemates A–D, phenylpropanoid esters from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga racemosa. Phytochemistry. 2002;61:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarry H, Harnischfeger G, Düker EM. Studies on the endocrine efficacy of the constituents of Cimicifuga racemosa: 2. In vitro binding of constituents to estrogen receptors. Planta Med. 1985;51:316–319. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennelly EJ, Baggett S, Nuntanakorn P, Ososki AL, Mori SA, Duke J, Coleton M, Kronenberg F. Analysis of thirteen populations of black cohosh for formononetin. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:461–467. doi: 10.1078/09447110260571733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panossian A, Danielyan A, Mamikonyan G, Wikman G. Methods of phytochemical standardisation of rhizoma Cimicifugae racemosae. Phytochem Anal. 2004;15:100–108. doi: 10.1002/pca.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang B, Kronenberg F, Balick MJ, Kennelly EJ. Analysis of formononetin from black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) Phytomedicine. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.06.007. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foldes J. The actions of an extract of Cimicifuga racemosa. Ärztl Forsch. 1959;13:623–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eagon CL, Elm MS, Teepe AG, Eagon PK. Medicinal botanicals: Estrogenicity in rat uterus and liver. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1997;38:2293. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eagon PK, Tress NB, Ayer HA, Wiese JM, Henderson T, Elm MS, Eagon CL. Medicinal botanicals with hormonal activity. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1980;40:161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarry H, Leonhardt S, Duls C, Popp M, Christoffel V, Spengler B, Theiling K, Wuttke W. 23rd International LOF Symposium on Phyto-oestrogens. University of Gent; Belgium: 1999. Organ-specific effects of Cimicifuga racemosa in brain and uterus. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarry H, Harnischfeger G. Studies on the endocrine efficacy of the constituents of Cimicifuga racemosa: 1. Influence on the serum concentration of pituitary hormones in ovariectomized rats. Planta Med. 1985;51:46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duker E-M, Kopanski L, Jarry H, Wuttke W. Effects of extracts from Cimicifuga racemosa on gonadotropin release in menopausal women and ovariectomized rats. Planta Med. 1991;57:420–424. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nisslein T, Freudenstein J. Effects of black cohosh on urinary bone markers and femoral density in an ovx-rat model. Osteoporosis Int Abstr. 2000:504. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freudenstein J, Dasenbrock C, Nisslein T. Lack of promotion of estrogen dependent mammary gland tumors in vivo by an 2-propanolic black cohosh extract. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3448–3452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Burdette JE, Xu H, Gu C, Bhat KPL, van Breemen RB, Booth N, Constantinou AI, Pezzuto JM, Fong H, Farnsworth N, Bolton J. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of plant extracts for the potential treatment of menopausal symptoms. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:2472–2479. doi: 10.1021/jf0014157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burdette JE, Liu J, Chen SN, Fabricant DS, Piersen CE, Barker EL, Pezzuto JM, Mesecar A, Van Breemen RB, Farnsworth NR, Bolton JL. Black cohosh acts as a mixed competitive ligand and partial agonist of the serotonin receptor. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:5661–5670. doi: 10.1021/jf034264r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lupu R, Mehmi I, Atlas E, Tsai MS, Pisha E, Oketch-Rabah HA, Nuntanakorn P, Kennelly EJ, Kronenberg F. Black cohosh, a menopausal remedy, does not have estrogenic activity and does not promote breast cancer cell growth. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1407–1412. doi: 10.3892/ijo.23.5.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robbins C. Medicine from U.S. Wildlands: An assessment of native plant species harvested in the United States for medicinal use and trade and evaluation of the conservation and management implications. Prepared for USDA Forest Service and The Nature Conservancy. TRAFFIC North Am. 1999 July [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chromadex black cohosh adulteration products list. [June 16, 2005]; Available at http://www.chromadex.com/NewProducts/Black_Cohosh.pdf.

- 34.Slifman NR, Obermeyer WR, Aloi BK, Musser SM, Correll WA, Cichowicz SM, Betz JM, Love LA. Contamination of botanical dietary supplements by Digitalis lanata. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:806–811. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumenthal M. Industry alert: Plantain adulterated with digitalis. HerbalGram. 1997;40:28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harkey MR, Henderson GL, Gershwin ME, Stern JS, Hanckman RM. Variability in commercial ginseng products: An analysis of 25 preparations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:1101–1106. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.6.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He K, Zheng BL, Kim CH, Rogers LL, Zheng QY. Direct analysis and identification of triterpene glycosides by LC/MS in black cohosh, Cimicifuga racemosa, and in several commercially available black cohosh products. Planta Med. 2000;66:635–640. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang HK, Sakurai N, Shih CY, Lee KH. LC/TIS-MS fingerprint profiling of Cimicifuga species and analysis of 23-Epi-26-deoxyactein in Cimicifuga racemosa commercial products. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:1379–1386. doi: 10.1021/jf048300d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Compton JA, Culham A, Jury SL. Reclassification of Actaea to include Cimicifuga and Souliea (Ranunculaceae): phylogeny inferred from morphology, nrDNA, ITS, and cpDNA trnL-F sequence variation. Taxon. 1998;47:593–634. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu XM, Song LR. Zhong Hua Ben Cao. Vol. 3. Shanghai Science and Technology Press; Shanghai: 1999. pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blumenthal M. The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. American Botanical Council; Austin, Texas: 2003. pp. 13–409. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.