Abstract

Background

Certain parenting styles are influential in the emergence of later mental health problems, but less is known about the relationship between parenting style and later psychological well-being. Our aim was to examine the association between well-being in midlife and parental behaviour during childhood and adolescence, and the role of personality as a possible mediator of this relationship.

Method

Data from 984 women in the 1946 British birth cohort study were analysed using structural equation modelling. Psychological well-being was assessed at age 52 years using Ryff’s scales of psychological well-being. Parenting practices were recollected at age 43 years using the Parental Bonding Instrument. Extraversion and neuroticism were assessed at age 26 years using the Maudsley Personality Inventory.

Results

In this sample, three parenting style factors were identified : care; non-engagement; control. Higher levels of parental care were associated with higher psychological well-being, while higher parental non-engagement or control were associated with lower levels of psychological well-being. The effects of care and non-engagement were largely mediated by the offspring’s personality, whereas control had direct effects on psychological well-being. The psychological well-being of adult women was at least as strongly linked to the parenting style of their fathers as to that of their mothers, particularly in relation to the adverse effects of non-engagement and control.

Conclusions

This study used a prospective longitudinal design to examine the effects of parenting practices on psychological well-being in midlife. The effects of parenting, both positive and negative, persisted well into mid-adulthood.

Keywords: Life course, parenting, personality, psychological well-being, well-being

Introduction

A vast body of research shows that parental attitudes and behaviours, often called parenting style, have an effect on child and adolescent mental health and behaviour. Parenting styles have been found to play a causal role in psychosocial development, social competence and academic performance, as well as in the emergence of depression, anxiety and problem behaviour (see reviews by Baumrind, 1991; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Cassidy & Shaver, 1999; Collins et al. 2000).

Research on the relationship between parenting style and childhood outcomes is relatively straightforward since investigators can survey both the parent(s) and the child or adolescent. There are fewer studies on the relationship between parenting style as reported by the parent and outcomes in young adulthood or in later life because of the difficulty inherent in obtaining information from the parents of representative samples of adults. For this reason, most studies that have investigated the relationship between parenting style and outcomes in adult children have used retrospective reports, i.e. recollections by respondents of their parents’ childrearing practices. The majority of such studies, whether undertaken on clinical or non-clinical samples, have focused on adult psychopathology outcomes. Parenting styles, in particular authoritarian or emotionally cold parenting, have been consistently linked to subsequent mental health problems in adulthood (Parker, 1979; Parker et al. 1987, 1997; Rodgers, 1996; Kendler et al. 2000; Sakado et al. 2000; Enns et al. 2002; Reti et al. 2002a; Rohner & Britner, 2002; Heider et al. 2006).

A few studies have also looked at positive outcomes and have shown that either a caring or an authoritative parenting style (which combines warmth and clear guidance) is linked to the absence of negative outcomes or the presence of positive adult outcomes such as dispositional optimism (Korkeila et al. 2004), happiness (Furnham & Cheng, 2000), life satisfaction and self-efficacy (Flouri, 2004) and educational attainment or cognitive function (Dornbusch et al. 1987; Singh-Manoux et al. 2006; Martin et al. 2007). The recent focus on positive psychological outcomes reflects the rapidly expanding research interest in the concept of well-being, which is conceptualized as more than simply the absence of psychopathology (Ryff & Singer, 1998; Diener et al. 1999; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Huppert et al. 2005).

Well-being research has drawn on two broad traditions : one focuses on happiness, life satisfaction and the balance of positive and negative emotions – ‘hedonic’ well-being (Bradburn, 1969; Diener et al. 1999; Kahneman et al. 1999); the other is concerned with human potential, self-determination and personal growth – ‘eudaemonic’ well-being (Ryff, 1989; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryan et al. 2008; Ryff & Singer, 2008). Ryan & Deci (2001) suggest that well-being arises from the fulfilment of three basic psychological needs: autonomy; competence; relatedness. Ryff has proposed that psychological (eudaemonic) well-being comprises six dimensions of positive functioning : autonomy; environmental mastery; personal growth; positive relations with others; purpose in life; self-acceptance (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Keyes, 1995).

The few studies that have investigated the role of parenting in the development of psychological well-being have mainly been undertaken in student or young adult samples and have used limited (often single-item) measures of well-being. Only one study to date appears to have examined the relationship between parenting and a broad range of eudaemonic well-being measures. An & Cooney (2006) analysed data from a large US sample aged 23–74 years who had been asked several questions about their parents’ affection and support and in whom psychological well-being was measured at the same time using five subscales of the short 18-item version of the Ryff Psychological Well-being (RPWB) Scale (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Respondents who recalled positive relationships with their parents in childhood had better psychological well-being.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the long-range association between parenting style and psychological well-being in mid-adulthood. Using data from the 1946 British birth cohort study, we employed a prospective longitudinal design to establish whether the patterns of parenting identified as important in earlier stages of life are maintained into mid-adulthood. We used a retrospective parenting measure, the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) of Parker et al. (1979) together with a comprehensive measure of psychological well-being, a 42-item version of the RPWB Scale (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). In light of the strong association between personality and well-being found in previous studies (e.g. Costa & McCrae, 1980; de Neve & Cooper, 1998: Diener & Lucas, 1999; Abbott et al. 2008; Steel et al. 2008), we assessed the potential mediating role of the child’s personality, specifically, the dimensions of extraversion and neuroticism, in the relationship between parental style and well-being in mid-adulthood.

Method

Sample

The sample for this study comprised participants in the Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD), also known as the 1946 British birth cohort study. The NSHD is a stratified sample of singleton births occurring to married parents in England, Scotland and Wales during the week of 3–9 March 1946 (Wadsworth, 1991; Wadsworth et al. 2006). The sampling design was based on father’s socio-economic status; all births from non-manual and agricultural backgrounds were included, and a random sample of one in four births from manual social class backgrounds (the most common status). The cohort sample originally included 5362 individuals (2547 women), on whom data have been collected at regular intervals since childhood. A comparison between the sample retained at ages 43 and 53 years and population census data has shown that, after weighting, cohort members are broadly representative of the national population of a similar age (Wadsworth et al. 2003).

An annual substudy of women’s health in midlife was undertaken by postal questionnaire between the ages of 47–54 years. This study included 1778 (70%) of the original cohort of women; the others had died (6%), previously refused to take part (12%) or lived abroad and were not in contact with the study or could not be traced (13%). The psychological well-being scale (see details below) was included in the Women’s Health Survey (WHS) at age 52 years and was sent to 1421 women who had completed at least one WHS questionnaire in the previous 2 years. There is no comparative data on psychological well-being available for male survey members.

Measures

The Parental Bonding Instrument

The PBI (Parker et al. 1979) is a self-report questionnaire that contains 25 items, each describing a parental attitude toward the respondent. Respondents are required to rate the parent on a 1–4 scale (‘very like’ to ‘very unlike’). In total, 24 PBI items were administered in the NSHD when the survey members were aged 43 years, with instructions to consider the period up to the age of 16 years (see Appendix 1 for item listing).

Dimensional analysis of the NSHD sample using factor analytic models in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2004) led to a three-factor structure. The care factor corresponded to Parker et al.’s (1979) original care factor but their control factor split into two, which we labelled non-engagement and control. A similar factor structure was found for mothers and fathers (Appendix 1). Comparable three-factor structures have also emerged in previous studies (Cubis et al. 1989; Kendler, 1996; Murphy et al. 1997; Cox et al. 2000; Enns et al. 2002; Reti et al. 2002a, Lichtenstein et al. 2003), although naming conventions have varied. For example, the factor we labelled non-engagement has also been referred to as authoritarianism (Kendler, 1996; Heider et al. 2006), encouragement of behavioural freedom (Murphy et al. 1997) or behavioural restrictiveness (Reti et al. 2002a). The factor we call control is sometimes referred to as overprotection (Cox et al. 2000; Heider et al. 2005), protectiveness (Parker, 1979) or denial of psychological autonomy (Reti et al. 2002a).

The PBI has good internal and external construct validity and yields reliable scores in general population and clinical samples. Recollections of parenting styles remain stable even when re-assessed after a 20-year period (Wilhelm et al. 2005) and, despite concerns to the contrary, do not appear to be greatly affected by current mood (Parker, 1981; Gotlib et al. 1988; Duggan et al. 1998).

Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-being

A 42-item version of the RPWB scale was provided for the NSHD by Ryff (personal communication) and comprised seven questions for each of the six dimensions. A total of 20 items were positively worded and 22 negatively worded. The response format was six ordered categories labelled from ‘disagree strongly’ to ‘agree strongly’. A full description of the design and development of the RPWB scales is available elsewhere (Ryff, 1989).

Our modelling of the Ryff items incorporated recommendations from prior psychometric investigations of the RPWB (e.g. Abbott et al. 2006, 2009; Springer & Hauser, 2006). Specifically, Abbott et al. (2006), using data from the 1946 birth cohort, demonstrated that construct variance could be separated from methodological artefacts using factors comprising positive and negative item content. Their work also showed that four of the six dimensions of well-being (environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life and self-acceptance) were sufficiently highly correlated to load strongly on a second-order well-being factor measuring general well-being.

Maudsley Personality Inventory

Study members completed six neuroticism and six extraversion items from the Maudsley Personality Inventory (MPI; Eysenck, 1959) at age 26 years. The MPI was a precursor of the Eysenck Personality Inventory (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1964). The items used a three-category response format: ‘no’; ‘don’t know’; ‘yes’.

Analysis sample

The analysis was undertaken on 984 women survey members who had fewer than six items missing on the RPWB scale, four or fewer items missing on the PBI and had undertaken a personality assessment at age 26 years. Cohort members who had taken part in the WHS and met these criteria were of higher social class, better educated and more likely to be married than those who were not included in the study, although there were no significant differences in their employment status.

Statistical modelling

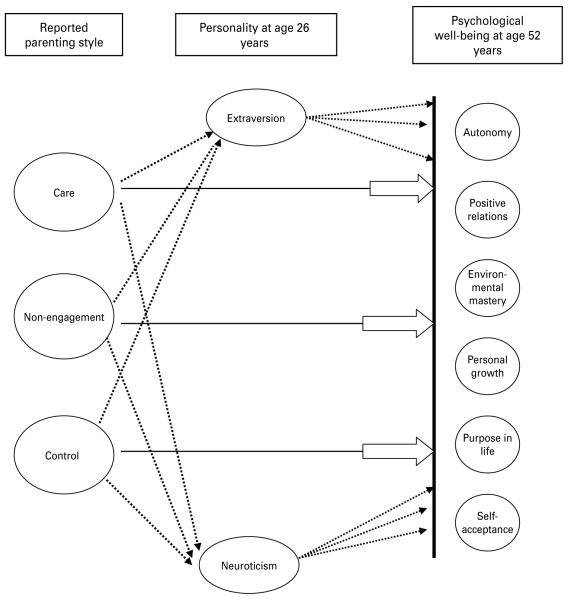

Analyses were carried out within a structural equation modelling framework. A structural equation model is a hypothesized pattern of directional and non-directional relationships among a set of manifest (observed) variables and latent (unobserved) variables (or factors). We employed a general formulation of the latent variable structural equation model, which is more suitable than traditional covariance structure analysis when ordinal/categorical measures are used as indicators of underlying constructs. Model estimation employed the robust weighted least squares approach (mean and variance adjusted weighted least square estimator) in Mplus version 4.2 (Muthén & Muthén). A graphical depiction of the model is shown in Fig. 1. It incorporates both the direct effects of maternal or paternal style on psychological well-being and indirect effects mediated through the survey member’s (i.e. the offspring’s) personality. Separate analyses were carried out for mothers and fathers. A similar model that incorporates the second-order factor was also applied.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual path diagram of associations between parenting style, personality and psychological well-being. Structural equation model showing latent variables for scores on the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI – maternal or paternal care, non-engagement and control), personality (extraversion and neuroticism) and Ryff’s Psychological Well-being (RPWB) Scale. Each RPWB dimension is associated with nine paths : three direct (—) (one for each of care, non-engagement, control); three indirect (- - -) via extraversion; three indirect via neuroticism. Correlations between the three PBI factors and between the six PWB factors are not displayed due to model complexity. Method factors for RPWB item wording are also not shown. See Abbott et al. (2006, fig. 1) for a complete representation of the RPWB measurement model used here. Two separate models were used, one for maternal parenting style and one for paternal parenting style.

The model did not include sociodemographic variables since it has been shown within the 1946 study that PBI scores are not associated with parental education, parental social class or material conditions (Rodgers, 1996) and because sociodemographic variables only account for a small percentage of variance in well-being outcomes (Argyle, 1999; Abbott et al. 2008). Nor did the analyses include weighting to make the sample more representative of the population, since the NSHD recommends that this procedure is only required when data on prevalence or incidence are reported.

Model fit was examined by four criteria : the comparative fit index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990); the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) (Tucker & Lewis, 1973); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Steiger, 1990) and the weighted root mean residual (WRMR) (Yu, 2002). Models are generally seen as having ‘moderate to good fit’ if they achieve >0.95 on the CFI and TLI, a RMSEA value of ≤0.06 and WRMR <1.0 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Yu, 2002).

Results

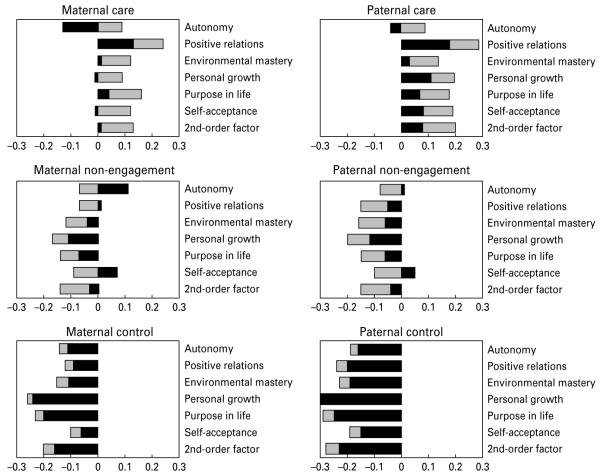

Reported characteristics of the parents up to the time the cohort member was 16 years old were associated with psychological well-being at age 52 years. This can be seen in Table 1 and Fig. 2, which show the standardized structural regression coefficients. These summarize the linear association between measures in the same way as a conventional regression β coefficient. Significant regression coefficients (p<0.05) are shown in bold.

Table 1.

Structural coefficients of direct and indirect associations between parenting style, personality and psychological well-being*

| Autonomy | Positive Relations | Environmental Mastery | Personal Growth | Purpose in Life | Self-Acceptance | Second-factora | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal care | Total | −0.04 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Direct | −0.13 | 0.13 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Indirect total | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| Indirect (E) | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

| Indirect (N) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| Paternal care | Total | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| Direct | −0.04 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

| Indirect total | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | |

| Indirect (E) | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

| Indirect (N) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| Maternal non-engagement | Total | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.17 | −0.15 | −0.03 | −0.11 |

| Direct | 0.11 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.11 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.03 | |

| Indirect total | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.08 | |

| Indirect (E) | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.05 | |

| Indirect (N) | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | |

| Paternal non-engagement | Total | −0.07 | −0.15 | −0.17 | −0.20 | −0.15 | −0.06 | −0.15 |

| Direct | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.12 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.04 | |

| Indirect total | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.11 | |

| Indirect (E) | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.07 | |

| Indirect (N) | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 | |

| Maternal control | Total | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.14 | −0.26 | −0.24 | −0.10 | −0.19 |

| Direct | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.24 | −0.21 | −0.06 | −0.16 | |

| Indirect total | −0.003 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 | |

| Indirect (E) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| Indirect (N) | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.03 | |

| Paternal control | Total | −0.19 | −0.23 | −0.23 | −0.33 | −0.29 | −0.19 | −0.28 |

| Direct | −0.16 | −0.20 | −0.19 | −0.30 | −0.25 | −0.15 | −0.23 | |

| Indirect total | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.05 | |

| Indirect (E) | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.02 | |

| Indirect (N) | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.03 |

Second-order well-being factor comprising environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life and self-acceptance (see Abbott et al. 2006)

Significant coefficients are shown in bold; figures rounded to two decimal places.

Model fit: maternal (n=984) χ2: 1211.9 [degrees of freedom (df)=397] p <0.001 ; comparative fit index (CFI)=0.94, Tucker Lewis index (TLI)=0.97, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.05, weighted root mean residual (WRMR)=1.38; paternal (n=946), χ2 : 1099.4 (df=360) p<0.001 ; CFI=0.95, TLI=0.97, RMSEA=0.05, WRMR=1.35.

Fig. 2.

Plots of standardized structural coefficients. Bars represent the absolute value of the total effect (■, direct;  , indirect).

, indirect).

Parental care

An estimate of the overall (total) effect of parental care is provided in Table 1. Maternal care was significantly and positively associated with positive relations, purpose in life, self-acceptance and the general well-being (second-order) factor. Paternal care was significantly and positively associated with positive relations, environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life, self-acceptance and the general well-being factor. The total effect of care was broken down into a direct and an indirect effect. The coefficients labelled ‘indirect’ in Table 1 represent the effects attributable to the path from parenting to RPWB via the offspring’s personality (extraversion or neuroticism). Most effects of care were indirect, mediated through the two personality latent variables, but most strongly through extraversion (Table 1, Fig. 2). The indirect effects of care were significant on all six RPWB dimensions and the general well-being factor for both the mother and the father. Examination of the direct effect, however, shows that over and above the effect of the personality of cohort members, care impacted directly on autonomy and positive relations. For positive relations with others, the direct effect of care was significant and in the positive direction for both mothers and fathers. For autonomy, however, the direct effect of care was significant and negative in the case of maternal care and there was a similar but non-significant trend for fathers.

Parental non-engagement

There was no overall (total) effect of mother’s non-engagement on the well-being measures, but there was a significant indirect association with environmental mastery, purpose in life and self-acceptance, as well as the general well-being factor, although neither of the individual indirect paths through extraversion or neuroticism reached significance. The total effect of father’s non-engagement showed a significant negative association with personal growth. When the total effect was broken down into its components, there was a significant and negative indirect association with all six dimensions of psychological well-being and the general well-being factor, and the mediating effect was stronger through neuroticism than extraversion. There were no significant direct effects of non-engagement for either the mother or father.

Parental control

The effects of parental control were relatively large and universally negative. The overall effect of maternal control was significant on all dimensions except self-acceptance. The effect of paternal control was significant on all six dimensions. Both maternal and paternal control was strongly related to the general well-being factor. All of the significant effects of control were direct; they were not influenced by the personality of the cohort member. In the case of maternal control, the direct effect was significant on personal growth and purpose in life. For paternal control, the direct effect was significant on all six well-being dimensions. Table 1 and Fig. 2 show that the dimensions that are most strongly influenced by parental control are personal growth and purpose in life.

Discussion

This study has extended our knowledge of the long-term effects of parents’ childrearing practices on their offspring’s psychological outcomes in two important ways. First, it analyses data from the longest running British birth cohort study, examining an adult sample that is older than any previously reported in a prospective longitudinal study of parenting style. This allows us to establish the extent to which parental practices that are known to influence child, adolescent and young adult behaviours continue to exert an effect later in life. Second, the study focuses on positive psychological outcomes and provides richly textured information about the relationship between parenting practices and multiple dimensions of psychological well-being. This contrasts with the usual emphasis on pathological outcomes and the more limited measures of well-being (sometimes one or two items, often restricted to hedonic well-being) used in the few existing population-based studies of positive adult outcomes (Furnham & Cheng, 2000; Flouri, 2004; Korkeila et al. 2004). Even the one study that employed a similar measure of psychological well-being (the 18-item Ryff scale) used a total score rather than investigating multiple dimensions of well-being (An & Cooney, 2006).

The present study has a number of other innovative features. Since it is known that personality is strongly linked to well-being (Costa & McCrae, 1980; de Neve & Cooper, 1998; Diener et al. 1999; Abbott et al. 2008; Steel et al. 2008), we have examined the extent to which the personality traits of extraversion and neuroticism, measured in the cohort members, mediated the effect of parental style on adult well-being. Further, because of the longitudinal design of the cohort study, key measures come from different times in the life course, thereby avoiding the confounding that can occur when measures are made concurrently and may be inflated by the effect of current mood or a common contextual effect. Specifically, personality was assessed when cohort members were 26 years old, parental behaviour assessed retrospectively when they were 43 years old and psychological well-being when they were aged 52 years.

The principal finding is that in this population there is a moderate but robust link between reported parenting behaviour up until age 16 years and psychological well-being in midlife. We found that, overall, high levels of care were positively associated with psychological well-being, while low engagement and, most notably, high control were negatively associated. Our findings suggest that women in midlife are more likely to flourish if their parents were warm and caring, shared interest and provided guidance rather than allowing them to do whatever they wanted and respected their need for autonomy and privacy, rather than being controlling, overprotective or intrusive.

A high level of parental care was positively associated with most well-being dimensions, but the strongest effect of care was seen on positive relationships. This is consistent with the classical studies of attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969, 1988), which emphasized the relationship between the type and amount of care experienced during early childhood and the later development of interpersonal relationships. Our study has demonstrated prospectively that the effects of parental care on relationships are still influential in the sixth decade of life.

A surprising finding is that high parental care was associated with low autonomy, significantly so in the case of mother’s care. Behaving in an autonomous way is usually regarded as a positive characteristic and studies undertaken in the context of self-determination theory have found that a high level of maternal nurturing is associated with autonomous behaviours, such as intrinsic motivation and affiliative or non-materialistic values (e.g. Kasser et al. 1995), which in turn are associated with a reduced risk of mental health problems (Kasser and Ryan, 1993). So how can we account for our apparently discrepant findings ? The term autonomy literally means ‘self-governing’ and accordingly refers to the experience of making choices freely and willingly. Autonomy should not be equated with independence or individualism, since a person can choose freely and willingly to depend on others or accept social norms (Chirkov et al. 2003). However, Ryff’s definition of autonomy is rather different; she defines an autonomous person as someone who is ‘self-determining and independent, able to resist pressure to think and act in certain ways’ (Ryff 1989, p. 1072). This definition of autonomy as individualism or even defiance is very different from a definition that focuses on the underlying concept of choice or self-regulation. There is some evidence from cross-cultural studies that when autonomy is defined as individualism, it is negatively associated with well-being (e.g. Chirkov et al. 2003).

One of the most striking findings of our study is that the well-being of adult women is so strongly linked to the type of parenting received from their father. The reported level of care provided by her father was at least as important for the daughter’s well-being as that provided by her mother, while her father’s reported levels of non-engagement and control by the father exerted a greater effect than those of her mother. In general, the role of fathers in the psychological outcomes of their offspring has been far less well studied than that of mothers. Research on fathers has often focused on the impact of the father’s absence or abusive behaviour (e.g. Wallerstein, 1991; Amato & Sobolewski, 2001). More recently, there has been recognition that the full spectrum of normal paternal behaviour is relevant to their children’s psychological development (Flouri & Buchanan, 2003; Lamb, 2004; McLaren et al. 2004; Flouri, 2005; Washbrook, 2007). Studies cited earlier (Parker et al. 1995; Rodgers, 1996; Enns et al. 2002; Heider et al. 2006) have analysed the role of paternal behaviour on mental health problems in adults, but very little previous research has systematically examined the differential effects of maternal and paternal behaviour on adult well-being. Our findings make an important contribution by showing that women in their fifties are more likely to flourish if, during childhood and adolescence, their father was perceived as caring, engaged and non-controlling.

Further research is needed to establish the extent to which our finding about the important role of fathers for the well-being of their adult daughters applies to women in general, or is specific to the birth cohort we have studied. Women born in the UK in 1946 grew up in the context of high levels of family stability and post-war economic and social progress, including the inception of the National Health Service and universal access to education. Among this cohort, it was relatively rare for parents to be divorced so it is likely that fathers played a larger role in their children’s daily life than in subsequent birth cohorts, where rates of separation and divorce were very much higher (Ferri et al. 2003). On the other hand, the majority of the mothers of members of this cohort stayed at home rather than going out to work (Ferri et al. 2003), so one might expect that the influence of mothers would be larger in this cohort compared with later cohorts. The parents of children born in 1946 are also likely to have had different values and a different parenting style to those who became parents later in the century (e.g. Wadsworth & Kuh, 1997). Therefore, research in other cohorts or populations is needed to establish how far our findings can be generalized to other samples of women, or to men.

Psychological well-being can be conceptualized as positive mental health (e.g. Ryff & Singer, 1998; Huppert et al. 2005; Huppert, 2009), so it is instructive to compare our findings on well-being with population-based studies on the relationship between parenting practices and later mental health problems. In general, children of parents who are characterized as providing high levels of warmth or care fare better in terms of traditional mental health outcomes than children whose parents provided lower levels of care (e.g. Parker et al. 1995; Rodgers, 1996; Cox et al. 2000; Kendler et al. 2000; Enns et al. 2002; Heider et al. 2006; Reti et al. 2002a). Although in two-factor models, a high level of parental control has also been associated with adult mental disorders or psychological symptoms (Parker et al. 1995; Rodgers, 1996); in studies using a three-factor model, the non-engagement factor has no significant effect on mental health outcomes, whereas control does exert a significant (negative) effect, although its influence is less than that of care (Kendler et al. 2000; Enns et al. 2002; Heider et al. 2006). Some of these studies found comparable effects of maternal and paternal control (e.g. Rodgers, 1996; Kendler et al. 2000), while those that found a differential effect reported that maternal control was substantially more damaging for mental health than paternal control in both sons and daughters (Enns et al. 2002; Heider et al. 2006). There are therefore both similarities and differences in the reported effects of parenting practices on mental ill health compared with mental well-being. High parental care and low parental control are associated with good outcomes in both cases, but for well-being, at least in our sample of adult women, control exerts a more powerful effect than care. Non-engagement also exerts a substantial (negative) influence on well-being and fathers have a stronger influence than mothers.

This therefore indicates a strong association between personality and well-being (e.g. Costa & McCrae, 1980; de Neve & Cooper, 1998; Diener et al. 1999; Abbott et al. 2008; Steel et al. 2008) and between parenting practices and the personality of their offspring (e.g. Reti et al. 2002b). Our analysis showed that the offspring’s personality mediates the effect of some parenting dimensions. All the effects of non-engagement were mediated through the offspring’s personality and all the effects of control were independent of the offspring’s personality. Non-engagement was mediated through neuroticism and was not significantly related to extraversion.

There was, however, a more complex relationship between parental care, personality and psychological well-being. For four dimensions of well-being, which together make up the general well-being factor (environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life, self-acceptance), the cohort member’s personality appeared to have the major influence. Both extraversion and neuroticism were important, but extraversion had a larger effect. For autonomy and positive relations with others, there were direct effects of care as well as the indirect effects mediated through the offspring’s personality.

Our analysis focused on the directional pathway from parental behaviour to midlife well-being, and by examining the mediating effects of the cohort member’s personality, it implicitly recognizes that personality can be influenced by parental behaviour. However, it is possible that there could be a bi-directional relationship between how parents behave and the child’s personality; that is, the child’s personality could influence parental behaviour, just as parental behaviour could influence the development of the child’s personality. Our analysis focused on only one causal direction, reflecting the availability of variables at particular time points across the life course. We used a measure of parental behaviour up to the age of 16 years and a measure of personality obtained 10 years later at age 26 years. Nevertheless, we recognize that early aspects of a child’s personality or temperament could have led to a particular parenting style and that early personality shows continuity with personality assessed in young adulthood. These issues have been more fully addressed in a seminal study by Kendler (1996), who used the PBI to investigate the factors that influence both the parental behaviour and the personality of their adult daughters. In a large sample of American female twin pairs and their parents, he showed that the offspring’s temperament had a greater effect on the elicitation of parental warmth (care) than on the other two PBI factors. These findings have been replicated in a study of female twin pairs in Sweden (Lichtenstein et al. 2003). These results are consistent with our finding that the effects of parental care were primarily mediated through the cohort member’s personality, while parental control exerted a direct effect independent of the child’s personality. However, in our study, the offspring’s personality also mediated the effect of the parents’ non-engagement on well-being outcomes.

Conclusion

Recollections of parenting style were found to be associated with the psychological well-being of women in their fifties. The study advances knowledge of this relationship since it employed a prospective longitudinal design rather than relying on cross-sectional associations. It also highlights the influence that fathers can have on the well-being of their adult daughters. There is a need for further research on parental style and positive mental health amongst men and women in other population samples.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a project grant from The Leverhulme Trust entitled ‘Human Flourishing : A Life-course Approach’ F/09903/B. We thank Maureen Ashby and Julie Aston for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Appendix 1.

Appendix 1.

Factorial structure of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) for the 1946 British birth cohort studya

| Standardized loadings |

||

|---|---|---|

| Mother | Father | |

| Care | ||

| Appeared to understand my problems and worries |

0.90 | 0.85 |

| Spoke to me with a warm and friendly voice |

0.86 | 0.89 |

| Helped me as much as I needed | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Was affectionate to me | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| Seemed to understand what I needed or wanted |

0.83 | 0.83 |

| Enjoyed talking things over | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| Talked to me often | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| Praised me | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| Frequently smiled at me | 0.79 | 0.83 |

| Could make me feel better when I was upset |

0.78 | 0.83 |

| Made me feel I wasn’t wanted | 0.58 | 0.40 |

| Let me do those things I liked doingb | 0.48 | 0.42 |

| Non-engagement | ||

| Let me decide things for myself | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| Liked me to make my own decisions |

0.80 | 0.89 |

| Gave me as much freedom as I wanted |

0.61 | 0.64 |

| Let me dress in any way I pleased | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| Let me go out as often as I wanted | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| Let me do those things I liked doingb | 0.35 | 0.49 |

| Wanted me to grow up | 0.27 | 0.30 |

| Control | ||

| Invaded my privacy | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| Was overprotective of me | 0.77 | 0.59 |

| Tried to control everything I did | 0.75 | 0.81 |

| Felt I could not look after myself unless she/he was around |

0.69 | 0.59 |

| Tried to make me dependent on her/him |

0.55 | 0.57 |

The distribution of raw scores on the three PBI factors was broadly similar for mothers and fathers, with no significant differences in mean scores on the three factors.

Goodness-of-fit statistics were comparative fit index (CFI) 95.7, Tucker Lewis index (TLI) 98.5, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) 0.07, weighted root mean residual (WRMR) 1.44 for the maternal model and CFI 96.8, TLI 98.9, RMSEA 0.07, WRMR 1.39 for the paternal model.

One item was excluded from the factor analysis model ‘Tended to baby me’ because of low loadings on all three factors. One item from the original PBI ‘Seemed emotionally cold to me’ was not included in the National Survey of Health and Development questionnaire.

This item loaded on both the care and non-engagement factors.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest None.

References

- Abbott RA, Croudace TJ, Ploubidis GB, Kuh D, Richards M, Huppert FA. The relationship between early personality and midlife psychological well-being : evidence from a UK birth cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;43:679–687. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0355-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott RA, Ploubidis GB, Huppert FA, Kuh DJ, Wadsworth ME, Croudace TJ. Psychometric evaluation and predictive validity of Ryff’s psychological well-being items in a UK birth cohort sample of women. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:76. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott RA, Ploubidis GB, Huppert FA, Kuh D, Croudace TJ. An evaluation of the precision of measurement of Ryff’s Psychological Well-being scales in a population sample. Social Indicators Research. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9506-x. Published online : 1 September 1 2009. doi :10.1007/s11205–009–9506-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Sobolewski JM. The effects of divorce and marital discord on adult children’s psychological well-being. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:900–921. [Google Scholar]

- An JS, Cooney TM. Psychological well-being in mid to late life : The role of generativity development and parent-child relationships across the lifespan. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30:410–421. [Google Scholar]

- Argyle M. Causes and correlates of happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwartz N, editors. Well-being, the Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance abuse. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:56–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss : Attachment. Basic; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A Secure Base. Basic; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn NM. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being. Aldine Publishing Company; Chicago: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Shaver P. Handbook of Attachment Theory and Research. Guildford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chirkov V, Ryan R, Kim Y, Kaplan U. Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence : a self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2003;84:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Maccoby EE, Steinberg L, Hetherington EM, Bornstein MH. Contemporary research on parenting. The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist. 2000;55:218–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being : happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:668–678. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Enns MW, Clara IP. The Parental Bonding Instrument : confirmatory evidence for a three-factor model in a psychiatric clinical sample and in the National Comorbidity Survey. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35:353–357. doi: 10.1007/s001270050250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubis J, Lewin T, Dawes F. Australian adolescents’ perceptions of their parents. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;23:35–47. doi: 10.3109/00048678909062590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context : an integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- De Neve KM, Cooper H. The happy personality : a meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:197–230. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Lucas RE. Personality and subjective well-being. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-Being : The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. Sage Found; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith H. Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:276–302. [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, Ritter P, Leiderman H, Roberts DF, Fraleigh MJ. The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development. 1987;58:1244–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan C, Sham P, Minne C, Lee A, Murray R. Quality of parenting and vulnerability to depression : results from a family study. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:185–191. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns MW, Cox BJ, Clara I. Parental bonding and adult psychopathology : results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:997–1008. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck H. Manual of the Maudsley Personality Inventory. University of London Press; London: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck H, Eysenck S. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory. University of London Press; London: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri E, Bynner J, Wadsworth ME. Changing Britain, Changing Lives : Three Generations at the Turn of the Century (Bedford Way Papers) Institute of Education; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E. Psychological outcomes in midadulthood associated with mother’s child-rearing attitudes in early childhood. Evidence from the 1970 British birth cohort. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;13:35–41. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-0355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E. Father’s involvement and psychological adjustment in Indian and white British secondary school age children. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2005;10:32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E, Buchanan A. The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A, Cheng H. Perceived parental behaviour, self-esteem and happiness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35:463–470. doi: 10.1007/s001270050265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib I, Mount JH, Cordy NI, Whiffen VE. Depression and perceptions of early parenting : a longitudinal investigation. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;152:24–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider D, Matschinger H, Bernert S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC. Relationship between parental bonding and mood disorder in six European countries. Psychiatry Research. 2006;143:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider D, Matschinger H, Bernert S, Vilagut G, Martinez-Alonso M, Dietrich S, Angermeyer MC, ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators Empirical evidence for an invariant three-factor structure of the Parental Bonding Instrument in six European countries. Psychiatry Research. 2005;135:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cut-off criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis : conventional criteria versus alternative. Structural Equation Modelling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert FA. Psychological well-being : Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Applied Psychology : Health and Well-Being. 2009;1:137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert FA, Keverne B, Bayliss N, editors. The Science of Well-Being. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwartz N, editors. Well-Being : The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. The Russell Age Foundation; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan RM. A dark side of the American dream : correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1993;65:410–422. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan R, Zax M. The relations of maternal and social environments to late adolescents’ materialistic and prosocial values. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:907–914. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. Parenting : a genetic-epidemiologic perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:11–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA. Parenting and adult mood, anxiety and substance use disorders in female twins : an epidemiological, multi-informant, retrospective study. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:281–294. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkeila K, Kivelä SL, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M, Sundell J, Helenius H, Koskenvuo M. Childhood adversities, parent-child relationships and dispositional optimism in adulthood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004;39:286–292. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0740-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb M, editor. The Role of Father in Child Development. Wiley and Sons, Inc; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Ganiban J, Neiderhiser JM, Pedersen NL, Hansson K, Cederblad M, Elthammar O, Reiss D. Remembered parental bonding in adult twins : Genetic and environmental influences. Behavior Genetics. 2003;33:397–408. doi: 10.1023/a:1025317409086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Ryan R, Brooks-Gunn J. The joint influence of mother and father parenting on child cognitive outcomes at age 5. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2007;22:423–439. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren L, Hardy R, Kuh D. Positive and negative body-related comments and their relationship with body dissatisfaction in middle-aged women. Psychology and Health. 2004;19:261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Brewin CR, Silka L. The assessment of parenting using the parental bonding instrument : two or three factors ? Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:333–341. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 3rd edn Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Parental characteristics in relation to depressive disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;134:134–147. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Parental reports of depressives. An investigation of several explanations. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1981;3:131–140. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(81)90038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Gladstone G, Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Austin MP. Dysfunctional parenting : over-representation in non-melancholic depression and capacity of such specificity to refine sub-typing depression measures. Psychiatry Research. 1997;73:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Greenwald S, Weissman M. Low parental care as a risk factor to lifetime depression in a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1995;33:173–180. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)00086-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Kiloh L, Hayward L. Parental representations of neurotic and endogenous depressives. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1987;13:75–82. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(87)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1979;52:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Reti IM, Samuels JF, Eaton WW, Bienvenu OJ, 3rd, Costa PT, Jr., Nestadt G. Adult antisocial personality traits are associated with experiences of low parental care and maternal overprotection. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002a;106:126–133. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reti IM, Samuels JF, Eaton WW, Bienvenu OJ, 3rd, Costa PT, Jr., Nestadt G. Influences of parenting on normal personality traits. Psychiatry Research. 2002b;111:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B. Reported parental behaviour and adult affective symptoms. 1. Associations and moderating factors. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:51–61. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Britner PA. Worldwide mental health correlates of parents’ acceptance-rejection : Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Cross-Cultural Research. 2002;36:16–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials : a review of research on hedonic and eudaemonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R, Huta V, Deci EL. Living well : a self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;9:139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B. The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B. Know thyself and become what you are : a eudaemonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;9:13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sakado K, Kuwabara H, Sato T, Uehara T, Sakado M, Someya T. The relationship between personality, dysfunctional parenting in childhood, and lifetime depression in a sample of employed Japanese adults. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;60:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology. An introduction. American Psychologist. 2000;55:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Fonagy P, Marmot M. The relationship between parenting dimensions and adult achievement : Evidence from the Whitehall II study. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine. 2006;13:320–329. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1304_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer KW, Hauser RM. An assessment of the construct validity of Ryff’s scales of psychological well-being : method, mode and measurement effects. Social Science Research. 2006;35:1079–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Steel P, Schmidt J, Schultz J. Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:138–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification : An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME. The Imprint of Time : Childhood, History, and Adult Life. Clarendon Press; Oxford, UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Butterworth SL, Hardy RJ, Kuh DJ, Richards M, Langenberg C, Hilder WS, Connor M. The life course prospective design : an example of the benefits and problems associated with study longevity. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:2193–2205. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Kuh D. Childhood influences on adult health : A review of the recent work from the British 1946 national birth cohort study, the MRC National Survey of Health and Development. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 1997;11:2–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1997.d01-7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Kuh DJ, Richards M, Hardy RJ. Cohort profile : The 1946 National Birth Cohort (MRC National Survey of Health and Development) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;31:49–54. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein JS. The long-term effects of divorce on children : a review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:349–360. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washbrook E. CMPO Working Paper. University of Bristol; Bristol: 2007. Fathers, childcare and children’s readiness to learn. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K, Niven H, Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. The stability of the Parental Bonding Instrument over a 20-year period. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:387–393. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CU. Evaluating Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes. University of California; Los Angeles: 2002. [Google Scholar]