Abstract

Lateral ventricular meningiomas presenting with primary intraventricular hemorrhage are extremely uncommon. We report here a case of primary intraventricular hemorrhage attributable to a lateral ventricular meningioma. This case concerns a 46-year-old female patient who presented with sudden onset of headache. Computed tomography (CT), computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations showed hemorrhage from a ruptured tumor mass, which was pathologically confirmed as a transitional meningioma. The patient underwent surgical treatment and had a good prognosis. A retrospective review of eight previous cases of hemorrhage from ruptured lateral ventricular meningiomas revealed that hemorrhage of lateral ventricular meningiomas and hemorrhage of meningiomas at other intracranial sites have similar causes. The clinical and pathological features of ruptured lateral ventricular meningiomas are consistent with those of unruptured lateral ventricular meningiomas. As this clinical entity is extremely rare, attention is called for while performing differential diagnosis.

Keywords: lateral ventricle, meningioma, hemorrhage

Introduction

Lateral ventricular meningiomas are rare, with an incidence of approximately 0.5-3% out of all intracranial meningiomas 1-2. Lateral ventricular meningiomas usually have no notable clinical symptoms when they are small. As they grow larger, however, they often present with chronic elevation of intracranial pressure, visual field defects, ataxia, memory impairment, and limb weakness 3-6. Lateral ventricular meningiomas presenting with intraventricular hemorrhage are even more uncommon, and little is known about this clinical entity. Here we report such a case. To identify the clinical features of this type of meningioma, we also conducted a literature review of eight similar cases.

Case report

A 46-year-old female was admitted to the hospital due to a sudden onset of headache that had lasted for 5 hours. Physical examination showed neck stiffness and Kernig's sign but no other positive signs of the nervous system. Computed tomography (CT) showed a high-density space-occupying lesion in the trigone of the left lateral ventricle. Hemorrhage surrounded the lesion and formed a hematoma, which extended forward into the contralateral ventricle and affected the third and fourth ventricles (Figure 1). Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed no intracranial artery malformation. The medial blood vessels of the lesion in the trigone of the lateral ventricle were disordered, and the lesion was supplied by anterior and posterior choroidal arteries. Maximum intensity projection clearly revealed a high-density calcification shadow at the rear of the lesion, and the surrounding brain tissues were mildly compressed (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the area of the lesion was 2.86 cm × 2.68 cm with mixed T1WI and T2WI signals. The lesion was heterogeneous in density, and its center was cystic. Slightly high abnormal T1WI and T2WI signals were noted in the bilateral lateral ventricles, and fluid was visible in the occipital horn of the left lateral ventricle (Figure 3).

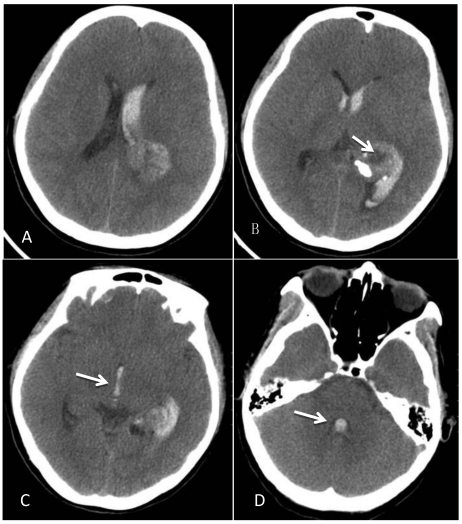

Figure 1.

CT at the time of onset of intraventricular hemorrhage. A-B: A space-occupying lesion in the trigone of the left lateral ventricle was observed; it had a low-density cystic shadow in the middle (arrow). A high-density calcification shadow was detected at the rear of the lesion, and the surrounding brain tissues were mildly compressed. C: Hemorrhage surrounded the lesion and formed a hematoma, which extended forward into the lateral ventricle, and the hemorrhage affected the third ventricle (arrow). D: The hemorrhage also affected the fourth ventricle (arrow).

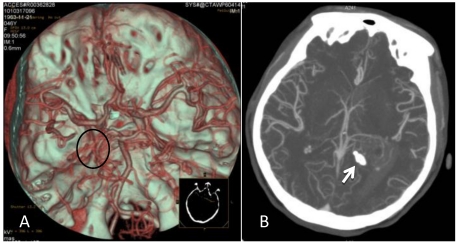

Figure 2.

CTA after the onset of intraventricular hemorrhage. A: No intracranial artery malformation was observed; medial blood vessels of the tumor in the trigone of the lateral ventricle were disordered, and the tumor was supplied by anterior and posterior choroidal arteries (oval area). B: Maximum intensity projection revealed a high-density shadow in the trigone of the left lateral ventricle; the surrounding vessels were disordered, and a high-density calcification shadow was detected at the rear of the lesion (arrow).

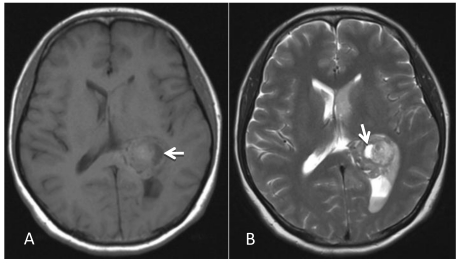

Figure 3.

MRI examination. A-B: A 2.86 cm × 2.68 cm space-occupying lesion was detected in the trigone of the left lateral ventricle; T1WI and T2WI showed mixed signals, and a cystic shadow was noted within the lesion. Slightly high abnormal T1WI and T2WI signals in the bilateral lateral ventricles were observed, and fluid was visible in the occipital horn of the left lateral ventricle (arrow).

An initial diagnosis of a space-occupying lesion with hemorrhage in the trigone of the left lateral ventricle was given based on the medical history, physical examinations, and auxiliary examinations. However, the nature of the lesion remained undetermined, and lesion resection was scheduled. The lesion was accessed using the left temporoparietal approach. After old blood clots were partly removed, a well-defined, red, parenchymatous tumor with a complete capsule was exposed. The tumor had abundant blood supply, and adhered slightly to the walls of the lateral ventricle. The central part of the tumor was cystic, and the root originated from the choroid plexus and had a clear arterial blood supply.

After controlling arterial blood supply, the surgery was successful, and the tumor was completely removed. Postoperatively, the patient recovered well. However, at day 7 the patient became depressed and then entered a confused state of mind. Physical examination revealed a dilated left pupil (4.5 mm in diameter), lack of a pupillary light reflex, and a paralyzed right limb accompanied by pathological reflex. Head CT showed severe edema surrounding the surgical field. The ipsilateral ventricle was compressed and deformed and the midline had shifted to the opposite side, which was considered to be brain herniation caused by cerebral edema. Emergency treatment with decompression via bone removal was performed (Figure 4). Postoperatively, the patient recovered well but developed left homonymous hemianopia. The patient was in a good state at the 6-month follow-up, but the hemianopia did not resolve.

Figure 4.

Postoperative CT. A: Re-examination at day 7 post operation showed that the tumor had been removed but that severe edema surrounded the lesion and the midline had shifted to the opposite side. B: After decompression, there was still edema surrounding the trigone of the lateral ventricle, but the midline was located in the middle.

Postoperative pathological results showed that the tumor was composed of fusiform cells. In addition to the observed hemorrhage and cystic changes, dilated, tortuous vessels were visible within the tissues. The shape of the cells was between that of endothelial and fibroblast types. Thus, the lesion was diagnosed as transitional meningioma (WHO-Grade I) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Pathological examination. A: The tumor was composed of fusiform cells; the shape of the cells was between that of endothelial and fibroblast types (i.e., transitional type; WHO-Grade I). B: Cystic cavities were seen in the tumor tissues (arrow). C: Patchy hemorrhage was observed inside the tumor, within which dilated tortuous blood vessels were observed (arrow).

Discussion

Meningiomas of the ventricular system are rare; most of these tumors arise in the left lateral ventricle and over 90% occur in the trigone 3,6,7. The clinical manifestations of lateral ventricular meningiomas depend largely on tumor size: A small tumor often causes no symptoms because the lateral ventricle has a relatively large compensating space, but notable symptoms, such as increased intracranial pressure and local neurological deficits, may appear when the tumor is large 8,9. However, lateral ventricular meningiomas presenting with intraventricular hemorrhage are extremely rare: Eight such cases have been reported to date 10-13. Herein we described one such case and conducted a review of other cases to increase our understanding of this disease.

The cause of hemorrhage from intraventricular meningioma is unknown. Several hypotheses have been proposed 14,15. First, the vascular network within the meningioma may rupture due to its abnormal development 16. Second, a rapidly growing meningioma or internal necrosis after venous thrombosis may lead to hemorrhage 17. Third, arteries that feed the meningioma are dilated and tortuous and thus lose the ability to regulate blood pressure fluctuation 18. Fourth, expansive growth of the meningioma stretches and tears bridging veins 19. Other factors, such as coagulation disorder inside the meningioma, peritumor edema, infarction within the tumor, and malignant transformation of the tumor may also result in hemorrhage of intracranial meningiomas 14. Of these hypotheses, the first one is the most widely accepted, but it still cannot explain all meningioma hemorrhages because not all meningiomas demonstrate abnormal blood vessel development 18,19. Thus, a combination of the aforementioned factors may play a part in this process 14.

Our analysis of the present case revealed the following: The meningioma was composed of fusiform cells; the shape of the cells was between that of endothelial and fibroblast types and no high grade malignant tumor cells were noted; dilated tortuous vessels surrounded by hemorrhage were visible in the tissues; and no necrosis or infarction was observed in the tumor tissues adjacent to the hemorrhagic area. Therefore, we concluded that the hemorrhage in this meningioma resulted from ruptured blood vessels, and that the hemorrhage infiltrated the tumor tissues due to the pressure gradient. Accordingly, the first and third hypotheses best explain the hemorrhage of this meningioma.

When an intraventricular meningioma is small, it may be easily overlooked because it can be submerged in an intraventricular hematoma once it ruptures. This is a common scenario for other ruptured intraventricular tumors causing hemorrhage. For example, Nishibayashi reported a case of central neurocytoma in the lateral ventricle 20, and Donovan described a case of teratoma in the lateral ventricle 21, both of which involved a small tumor with massive bleeding. The tumors could have been easily missed. The meningioma reported herein was located in the trigone of the lateral ventricle. No direct clinical symptoms resulting from the meningioma were shown, and the initial presenting symptom was from intraventricular hemorrhage.

For the meningiomas of the trigone of lateral ventricle, there are several approaches used, such as superior parietal lobe approach and parieto-occipital approach 22. In our case, we chose the temporoparietal approach instead of other approaches, because as shown by the CTA image, the lesion was supplied by anterior and posterior choroidal arteries, and maximum intensity projection clearly revealed a high-density calcification shadow at the rear of the lesion. It was convenient to control the arterial blood supply using the temporoparietal approach. The surgery was successful, and the tumor was completely removed after the control of arterial blood supply. However, at day 7 the patient became depressed and entered a confused state of mind. CT showed brain herniation due to the occurrence of cerebral edema. The mechanism of postoperative edema surrounding the surgical field in this case is different from the edema surrounding meningioma, which is associated with venous compression, tumor-related pressure, arterial blood supply and secretion of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor 23. In this case the postoperative edema surrounding the surgical field mainly resulted from surgical trauma after tumor removal.

By conducting a literature review, we identified eight previously reported cases of hemorrhage caused by ruptured lateral ventricular meningioma (Table 1). Among these, six were in females (75%), revealing a female predominance; age of onset ranged between 14 and 64 years (mean 43); five cases were located on the left side and three cases on the right side; and all were located in the trigone of the lateral ventricle. When stratified by pathology, five cases were fibroblastic type (62.5%), two cases were endothelial type, and one case was psammomatous type. The present case had similar age of onset, gender, location, and affected side as those of the previous cases, but it had a transitional pathological type, which differed from other cases. Overall, the clinical and pathological features of ruptured lateral ventricular meningioma causing hemorrhage are comparable to those of unruptured lateral ventricular meningioma without hemorrhage 3-6.

Table 1.

Patients presenting with the hemorrhage from lateral ventricular meningiomas

| Case | Author/Year | Age/Sex | Side | Histological type | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Askenasy/196010 | 34/F | Left | Endotheliomatous | Dead |

| 2 | Askenasy/196010 | 38/F | Left | Fibroblastic | Dead |

| 3 | Goran/196510 | 55/M | Right | Endotheliomatous | Persistent neurological deficit |

| 4 | Smith/197510 | 14/F | Left | Fibroblastic | Good recovery |

| 5 | Lang/199511 | 64/M | Left | Fibroblastic | Persistent neurological deficit |

| 6 | Murai/199610 | 39/F | Right | Fibroblastic | Persistent neurological deficit |

| 7 | Lee/200112 | 43/F | Right | Psammomatous | Good recovery |

| 8 | Bernd/200713 | 57/F | Left | Fibroblastic | Dead |

| 9 | Present case | 46/F | Left | Transitional | Good recovery |

Conclusion

In summary, meningiomas of lateral ventricles and those occurring in other intracranial sites share similar causes of rupture and hemorrhage, and ruptured lateral ventricular meningiomas manifest similar clinical and pathological characteristics as unruptured meningiomas in the lateral ventricle. Nevertheless, lateral ventricular meningiomas presenting with primary intraventricular hemorrhage are rarely seen. A small lateral ventricular meningioma is likely to be submerged in the hematoma once it bursts; hence, when patients present with meningiomas particular attention is warranted to avoid missed diagnosis and delayed treatment.

References

- 1.Nakamura M, Roser F, Bundschuh O. et al. Intraventricular meningiomas: a review of 16 cases with reference to the literature. Surg Neurol. 2003;59:491–503. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim EY, Kim ST, Kim HJ. et al. Intraventricular meningiomas: radiological findings and clinical features in 12 patients. Clin Imaging. 2009;33:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyngdoh BT, Giri PJ, Behari S. et al. Intraventricular meningiomas: a surgical challenge. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:442–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Criscuolo GR, Symon L. Intraventricular meningioma. A review of 10 cases of the National Hospital, Queen Square (1974-1985) with reference to the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1986;83:83–91. doi: 10.1007/BF01402383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim IY, Kondziolka D, Niranjan A. et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for intraventricular meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009;151:447–52. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertalanffy A, Roessler K, Koperek O. et al. Intraventricular meningiomas: a report of 16 cases. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:30–5. doi: 10.1007/s10143-005-0414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delfini R, Acqui M, Oppido PA. et al. Tumors of the lateral ventricles. Neurosurg Rev. 1991;14:127–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00313037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cushing H, Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas. Their Classification, Regional Behavior, Life History and Surgical End Results. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1938. pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatoe HS, Singh P, Dutta V. Intraventricular meningiomas: a clinicopathological study and review. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E9. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murai Y, Yoshida D, Ikeda Y. et al. Spontaneous intraventricular hemorrhage caused by lateral ventricular meningioma--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1996;36:586–9. doi: 10.2176/nmc.36.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang I, Jackson A, Strang FA. Intraventricular hemorrhage caused by intraventricular meningioma: CT appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1378–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee EJ, Choi KH, Kang SW. et al. Intraventricular hemorrhage caused by lateral ventricular meningioma: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2001;2:105–7. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2001.2.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romeike BF, Joellenbeck B, Skalej M. et al. Intraventricular meningioma with fatal haemorrhage: clinical and autopsy findings. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109:884–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DG, Park CK, Paek SH. et al. Meningioma manifesting intracerebral haemorrhage: a possible mechanism of haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2000;142:165–8. doi: 10.1007/s007010050019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modesti LM, Binet EF, Collins GH. Meningiomas causing spontaneous intracranial hematomas. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:437–41. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.45.4.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helle TL, Conley FK. Haemorrhage associated with meningioma: a case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:725–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.43.8.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruszkiewicz J, Doron Y, Gellei B. et al. Massive intracerebral bleeding due to supratentorial meningioma. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 1969;12:107–11. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1095292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloomgarden GM, Byrne TN, Spencer DD. et al. Meningioma associated with aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:24–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198701000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martínez-Lage JF, Poza M, Martínez M. et al. Meningiomas with haemorrhagic onset. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1991;110:129–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01400680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishibayashi H, Uematsu Y, Terada T. et al. Neurocytoma manifesting as intraventricular hemorrhage--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2006;46:41–5. doi: 10.2176/nmc.46.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donovan DJ, Smith AB, Petermann GW. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the velum interpositum presenting as a spontaneous intraventricular hemorrhage in an infant: case report with long-term survival. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2006;42:187–92. doi: 10.1159/000091866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zanini MA, Faleiros AT, Almeida CR. et al. Trigone ventricular meningiomas: surgical approaches. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69:670–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2011000500018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ono K, Hatada J, Minamimura K. et al. Delayed enlargement of brain edema after resection of intracranial meningioma: two case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2009;49:478–81. doi: 10.2176/nmc.49.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]