Abstract

Heart failure afflicts ~5 million people and causes ~300,000 deaths a year in the United States alone. Heart failure is defined as a deficiency in the ability of the heart to pump sufficient blood in response to systemic demands, which results in fatigue, dyspnea, and/or edema. Identifying new therapeutic targets is a major focus of current research in the field. We and others have identified critical roles for protein kinase C (PKC) family members in programming aspects of heart failure pathogenesis. More specifically, mechanistic data have emerged over the past 6–7 years that directly implicate PKCα, a conventional PKC family member, as a nodal regulator of heart failure propensity. Indeed, deletion of the PKCα gene in mice, or its inhibition in rodents with drugs or a dominant negative mutant and/or inhibitory peptide, have shown dramatic protective effects that antagonize the development of heart failure. This review will weigh all the evidence implicating PKCα as a novel therapeutic target to consider for the treatment of heart failure.

Introduction

The protein kinase C (PKC) family of Ca2+ and/or lipid-activated serine/threonine kinases function downstream of many membrane-associated signal transduction pathways [1]. Approximately 10 different isozymes comprise the PKC family, which are broadly classified by their activation characteristics. The conventional PKC isozymes (α, βI, βII, and γ) are Ca2+- and lipid-activated, while the novel isozymes (ε, θ, η, and δ) and atypical isozymes (ζ and λ) are Ca2+- independent but activated by distinct lipids [1]. PKC family members contain N-terminal regulatory and C-terminal catalytic domains separated by a flexible hinge region. In the absence of activating cofactors, the catalytic domain is subject to autoinhibition by the regulatory domain mediated, in part, by a pseudosubstrate sequence motif that resembles the consensus sequence for phosphorylation by PKC [2]. For the classical PKC isozymes, binding of Ca2+ and phosphatidylserine to the C2 domain leads to increased membrane association. Binding of diacylglycerol (DAG) to the zinc finger region of the C1 domain causes a conformational change, further enabling activation of the enzyme [3]. For all PKC isoforms, membrane translocation provides a mechanism to regulate substrate access through docking complexes such as RACKs, although PKC isoforms may also function when unbound and free in the cytosol or nucleus [4]. In addition to changes in phosphorylation and translocation of PKC, alterations in PKC levels can also affect activity and signaling, such as known changes documented during cardiac development and with pathological events. For example, PKCα, β, ε, and ζ, expression are high in fetal and neonatal hearts but decreases in adult hearts [5]. Select PKC isoforms also increase during transition to heart failure in humans, suggesting a reversion back to a neonatal phenotype [3].

With respect to the conventional isoforms, PKCα is the predominant subtype expressed in the mouse, human, and rabbit heart, while PKCβ and PKCγ are detectable but expressed at substantially lower levels [6–8]. Numerous reports have also associated PKCα activation or an increase in PKCα expression with hypertrophy, dilated cardiomyopathy, ischemic injury, or mitogen stimulation [1]. For example, hemodynamic pressure overload in rodents promotes translocation and presumed activation of PKCα during the hypertrophic phase or during later stages of heart failure [9–13]. Increased expression of PKCα was also observed following myocardial infarction [14,15]. Human heart failure has also been associated with increased activation of conventional PKC isoforms, including PKCα [15,16]. Thus, PKCα fits an important criterion as a therapeutic target; its expression and activity are increased during heart disease.

Genetic analysis of PKCα in the mouse: Regulation of cardiac contractility

1. PKCα gene-deleted mice

We and others have shown that PKCα functions as a fundamental regulator of cardiac contractility [17,18]. PKCα−/− mice showed an increase in cardiac contractile performance in multiple experimental systems. For example, closed-chest invasive hemodynamic assessment showed a 15–20% increase in maximum dP/dt at baseline, with a corresponding parallel increase in performance after β-adrenergic receptor stimulation. An ex vivo working heart preparation, which shows the intrinsic function of the heart, also revealed an increase in maximum dP/dt in hearts from PKCα−/− mice compared with wildtype control hearts [17]. Mechanistically, cardiac myocytes from PKCα−/− mice, but not PKCβγ−/− mice, showed enhanced contractility, Ca2+ transients, and Ca2+ loading in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) [17,19].

Importantly, PKCα−/− mice were protected against heart failure induced by pressure overload and myocardial infarction, against dilated cardiomyopathy induced by deleting the gene encoding muscle LIM protein (Csrp3), and against cardiomyopathy associated with overexpression of PP-1 [17,20]. It was speculated that the subtle but significant enhancement in cardiac contractility observed in PKCα−/− mice was the mechanism of protection from heart failure, although other mechanisms may have also contributed [17]. In contrast to PKCα−/− mice that are protected from heart failure following long-term pressure-overload stimulation or myocardial infarction injury, PKCβγ−/− mice showed more severe heart failure when stressed [19]. Indeed, mice overexpressing low levels of activated PKCβ showed no pathology at baseline and recovered function better following ischemic injury, observations that are in dramatic contrast with the known pathology associated with PKCα overexpression in the heart [17,21]. These results suggested that PKCα functions distinct from PKCβ and PKCγ in regulating cardiac contractility and heart failure susceptibility, again suggesting that inhibition of PKCα would be uniquely protective to the heart, while selective inhibition of PKCβ or PKCγ would have no effect or even be detrimental.

2. Dominant negative PKCα TG mice

To examine more precisely if PKCα functions in a myocyte autonomous manner to affect cardiac contractility and cardioprotection in vivo, we generated cardiac myocyte-specific transgenic mice using a tetracycline-inducible system to permit controlled expression of dominant negative PKCα (dnPKCα) in the heart [20]. Consistent with the proposed function of PKCα, induction of dominant negative PKCα expression in the adult heart mildly enhanced baseline cardiac contractility [20]. This increase in contractility was associated with a partial protection from long-term decompensation and secondary dilated cardiomyopathy after myocardial infarction injury. In the same study, PKCα−/− mice were examined and also shown to be partially protected from infarction-induced heart failure. Moreover, adenovirus-mediated gene therapy with a dominant-negative PKCα cDNA rescued heart failure in a rat model of cryo-infarction cardiomyopathy [6]. Thus, myocyte autonomous inhibition of PKCα protects the adult heart from decompensation and dilated cardiomyopathy after infarction injury.

3. PKCα TG mice

Transgenic mice expressing wild-type PKCα protein driven by the α-myosin heavy chain promoter were generated and analyzed [17]. Hearts from these mice showed an increase in autophosphorylation of PKCα with no compensatory changes in other PKC isozymes. PKCα transgenic mice manifested signs of cardiac hypertrophy at 6 months of age, although by 4 months they showed reduced ventricular performance, suggesting that a defect in contractility preceding any overt pathological changes [17]. This defect in ventricular performance, or maximal dP/dt, was even more pronounced at 6 and 8 months of age. To address the potential for secondary effects associated with a chronic elevation in PKCα activity, we also analyzed acute PKCα activation or inhibition in wildtype adult rat cardiac myocytes. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of wildtype or dominant-negative PKCα in adult myocytes reduced and enhanced myocyte contractility, respectively, as measured by peak shortening and maximal shortening velocity [17]. Thus, PKCα activation can chronically or acutely dampen myocyte function, suggesting that its inhibition might provide a therapeutic benefit by mildly enhancing contractile performance.

4. Transgenic mice with PKC translocation modifiers or protein inhibitors

Gain- and loss-of-function using transgenic expression of conventional PKC (cPKC) isoform translocation modifiers was also described [18]. Transgenic mice were generated using the cardiomyocyte-specific α-myosin heavy chain promoter to express peptides corresponding to either the PKCβ C2-C4 region (inhibits translocation of all cPKC isoforms) or homologous regions of PKCβ and RACK1 (enhances translocation of all cPKC isoforms) [18]. Although these peptides affect PKCβ and PKCα, the abundance of PKCα relative to other cPKCs in adult mouse heart (> 80% of myocardial cPKC) suggested that the observed effects were due to PKCα modulation. PKC activator mice gradually developed mild left ventricular dysfunction, while the cPKC inhibitor mice retained normal ventricular function through 1 year of age [18]. Importantly, cPKC activation diminished myocardial responsiveness to β-adrenergic receptor agonists, whereas PKCα inhibition enhanced β-adrenergic responsiveness and contractility [18]. The effects of PKCα were also assessed in the context of the Gαq overexpression model of cardiomyopathy (in which PKCα is transcriptionally upregulated). Inhibition of PKCα activity in Gαq hearts improved systolic and diastolic function, whereas further activation of PKCα caused a lethal restrictive cardiomyopathy. These results further support a pathological role for PKCα in worsening heart failure with pathologic stimulation.

Another putative PKC inhibitor, PICOT (PKC-interacting cousin of thioredoxin), has also been shown to enhance cardiac contractility in transgenic mice with cardiac-specific overexpression [22]. PICOT overexpression increased ventricular function of transgenic hearts and the contractility of isolated adult cardiomyocytes. Intracellular analysis revealed increases in myofilament Ca2+ responsiveness and increased rate of SR Ca2+ reuptake. These results provide additional evidence supporting the notion that inhibition of cPKC enhances cardiac contractile function.

Molecular mechanisms of action

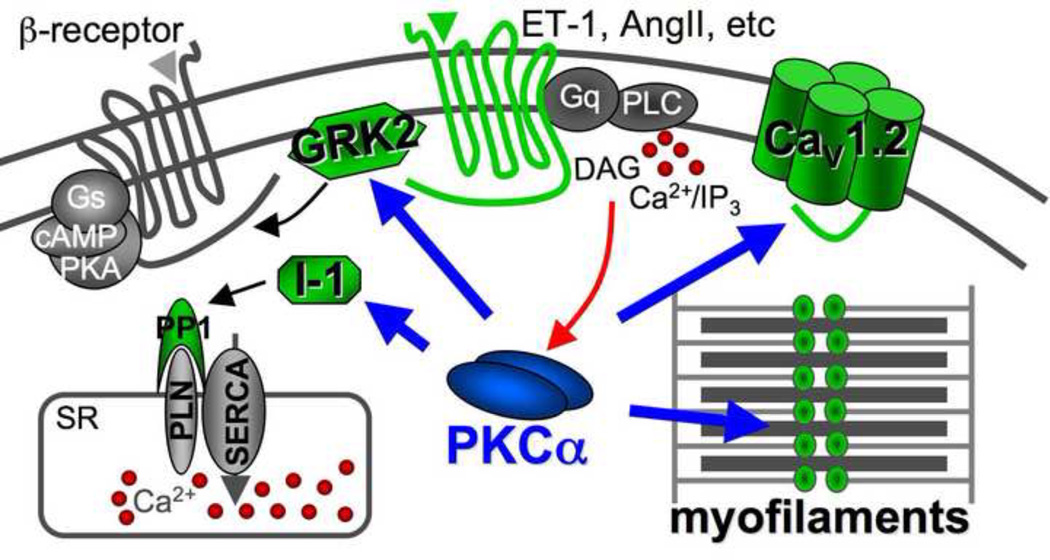

A number of independent molecular mechanisms have been associated with the known protection from heart failure by PKCα inhibition, although all of these mechanisms have so far been associated with modulation of cardiac contractility (Figure 1). The first identified mechanism whereby PKCα inhibition enhances cardiac contractility is through SR Ca2+ loading [17]. Specifically, PKCα phosphorylates inhibitor 1 (I-1) at Ser67, resulting in greater protein phosphatase 1 activity, leading to greater phospholamban (PLN) dephosphorylation and less activity of the SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA2) pump [17]. Less SERCA2 activity reduces SR Ca2+ load leading to reduced Ca2+ release during systole, hence reduced contractility. Thus, inhibition of PKCα with a drug or dominant negative mutant would reduce PP-1 activity for PLN, making PLN less inhibitory towards SERCA2 and leading to mild enhancements in SR Ca2+ load to augment contractility. Greater SR Ca2+ loads and cycling have been shown to benefit the mouse from numerous insults that would otherwise cause heart failure [23]. Indeed, gene therapy trials using SERCA2 overexpression in the hearts of humans with failure have already shown early promise (http://www.celladon.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=75&Itemid=54).

Figure 1.

Diagram of signaling in a cardiac myocyte showing how PKCα becomes activated by Gαq-coupled receptors leading to phospholipase C (PLC) activation and the liberation of DAG and Ca2+ (red arrow). Once activated, PKCα has 4 main mechanisms whereby it can alter cardiac function (blue arrows).

Another mechanism whereby PKCα can directly alter cardiac contractility is through phosphorylation of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) (Figure 1). Indeed, cardiac-specific activation of PKCα led to increased GRK2 phosphorylation and activity, blunted cyclase activity, and impaired β-agonist-stimulated ventricular function [24]. GRK2 is known to directly control β-adrenergic receptor function and cardiac contractility [25]. Consistent with these observations, mice overexpressing the cPKC activating peptide in the heart showed uncoupling in β-adrenergic receptors [18].

PKCα also appears to directly phosphorylate key myofilament proteins including cardiac troponin I (cTnI), cTnT, titin, and myosin binding protein C, which leads to decreased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and reduced contractility in myocytes [26–29]. These myofilament proteins could also be phosphorylated by other cPKC isoforms [30, 31]. Moreover, PKCα has also been shown to phosphorylate the α1c subunit of the L-type Ca2+ channel (Figure 1), an effect that could alter contractility as well [32]. By comparison, PKCβI, βII, and γ can also phosphorylate serine residues in the α1c subunit [32]. These data further suggest the possible promiscuous nature of the cPKCs in the regulation of protein phosphorylation, Ca2+ cycling, and cell contractility. Despite these similarities in targets, we believe that PKCα functions unique from PKCβ and γ in altering contractility because adult cardiac myocytes from PKCβ overexpressing TG mice showed increased Ca2+ transients and increased contractility [30], while PKCα overexpressing TG mice showed depressed cardiac contractility [17]. Moreover, myocytes from adult PKCα null hearts showed increased contractility and augmented Ca2+ transients [17].

In addition to these specific molecular targets that all appear to alter cardiac contractility, it remains possible that inhibition of PKCα protects the myocardium through other unknown mechanisms that are unrelated to contractility. For instance, PKC- mediated phosphorylation has been correlated with myofibril degeneration in cardiomyocytes, while preservation of myofilament integrity may represent another potential mechanism for the beneficial effects of PKC inhibition [33]. Other potential PKCα targets may include structural proteins, signaling proteins and transcription factors [34]. Outside of a myocyte intrinsic effect, PKCα inhibition can also protect the entire cardiovascular system by limiting thrombus formation through a platelet specific mechanism [35].

PKCα inhibitory drugs protect the rodent heart (translational data)

The results in genetically modified animal models and in isolated adult myocytes clearly show a cardioprotective effect with PKCα inhibition. Such results suggested that a nontoxic and tissue available pharmacological inhibitor with selectivity toward PKCα might be of significant therapeutic value. Thus, we and others carefully examined the effects of cPKC inhibitors of the bisindolylmaleimide class, such as ruboxistaurin (LY333531), Ro-32-0432 or Ro-31-8220, in different rodent heart failure models. For example, short-term infusion of Ro-32-0432 or Ro-31-8220 significantly enhanced contractility and left ventricular developed pressure in isolated mouse hearts [6]. Importantly, Ro-31-0432 or Ro-31-8220 did not significantly augment cardiac contractility in PKCα−/− mice, strongly supporting the conclusion that the biological effect of the bisindolylmaleimide compounds on contractility are due to PKCα. Moreover, general activation of both classic and novel PKC isozymes in the heart by short-term infusion of PMA produces a dramatic decrease in contractility in wildtype mice but not in PKCα−/− mice [6]. This result also suggests that PKCα is the primary negative regulator of cardiac contractility after global activation of all PKC isozymes in the heart. With respect to heart failure, short-term or long-term treatment with Ro-31-8220 in the Csrp3 null mouse model of heart failure augmented cardiac contractility and restored pump function. PKC inhibition with Ro-31-8220 or Ro-32-0432 also reduced mortality and cardiac contractile abnormalities in a mouse model of myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) [36].

Another PKCα/β inhibitor, ruboxistaurin, has been through late-stage clinical trials for diabetic macular edema and shown to be well tolerated and hence, was extensively analyzed in both mouse and rat models of heart failure [37]. Although ruboxistaurin was originally reported to be PKCβ selective [38], we determined that it was equally selective for PKCα (IC50 of 14 nmol/L for PKCα versus 19 nmol/L for PKCβII). Moreover, given that PKCα protein levels are much higher than PKCβ in the human and mouse heart [6], it further suggests that ruboxistaurin functions predominantly through a PKCα-dependent mechanism. Indeed, we directly measured cardiac contractility upon acute ruboxistaurin infusion in mice lacking either PKCα or PKCβ and -γ. We previously observed that ruboxistaurin increased baseline contractility by 28% in rats with acute infusion [6]. Acute infusion of ruboxistaurin also augmented cardiac contractility in wildtype and PKCβγ−/− mice but not PKCα−/− mice [19]. These results indicate that ruboxistaurin enhances cardiac function specifically through effects on PKCα but not PKCβ or PKCγ. In other words, all of the protective effects observed with ruboxistaurin in rodent models of heart disease are predominately dependent on PKCα inhibition.

Ruboxistaurin also prevented death in wildtype mice throughout 10 weeks of pressure-overload stimulation, reduced ventricular dilation, enhanced ventricular performance, reduced fibrosis, and reduced pulmonary edema comparable to or better than metoprolol treatment [19]. Ruboxistaurin was also administered to PKCβγ null mice subjected to pressure overload, resulting in less death and heart failure, further suggesting PKCα as the primary target of this drug in mitigating heart disease [19]. In addition, Boyle et al. showed that ruboxistaurin reduced ventricular fibrosis and dysfunction following myocardial infarction in rats [39]. Ruboxistaurin treatment also significantly decreased infarct size and enhanced recovery of left ventricular function and reduced markers of cellular necrosis in mice subjected to 30 min of ischemia followed by 48 h of reperfusion [40]. Connelly et al. demonstrated that ruboxistaurin attenuated diastolic dysfunction, myocyte hypertrophy, collagen deposition, and preserved cardiac contractility in a rat diabetic heart failure model [41]. These results in rodents overwhelmingly support the contention that PKCα inhibition with ruboxistaurin, or related compounds, protects the heart from failure after injury. Hence, cPKC inhibitors, such as ruboxistaurin, should be evaluated in heart failure patients, especially given its apparent safety in late phase clinical trials in humans [37]. A related cPKC inhibitory compound from Novartis, AEB071, was also shown to be safe in human clinical trials for psoriasis and could be an equally exciting candidate for translation in the heart failure area [42].

While there is a clear need for novel inotropes to support late-stage heart failure, there may also be a therapeutic niche in earlier stages of heart failure if the inotrope is selective. One unique aspect associated with PKCα inhibition is that contractility is only moderately increased, which may have a safer profile compared with traditional inotropes. In addition, PKC inhibition is not subject to significant desensitization as is characteristic of β-agonists [6]. More importantly, PKCα inhibition has a prominent effect on SR Ca2+ cycling and the myofilament proteins as a means for altering cardiac contractility. These mechanisms of action are significantly downstream of how traditional β-adrenergic receptor agonists function, and hence, might bypass the negative effects of traditional inotropes that promote arrhythmia and myocyte death. Inhibition of PKCα may also benefit a failing myocardium independent of contractility regulation because PKCα is involved in reactive signaling within the heart that participates in hypertrophy, pathological remodeling, and decompensation.

Important future considerations for bringing this to the clinic

Based on genetic experiments and various pharmacological studies discussed above, a more selective PKCα inhibitor would serve as a better therapeutic agent compared with existing cPKC inhibitors. For example, while the non-selective cPKC inhibitor ruboxistaurin also targets PKCβ and γ, inhibiting PKCα clearly predominates in providing protection to the heart [19]. Thus, a PKCα selective inhibitor would greatly reduce potential adverse effects and achieve greater efficacy, especially since PKCβγ double null mice appear to be slightly compromised (suggesting that PKCβγ might be mildly protective to the heart). Alternatively, expression of a dnPKCα protein in the heart by gene therapeutic strategies would achieve greater specificity and might provide a long-term benefit without the need for daily treatment with an orally available small molecule.

in vivo studies using larger animals such as dogs, sheep, and pigs would also help validate the translational potential of PKCα as a target for treatment of pathological cardiac remodeling and heart failure in humans. Studies in a large animal model are especially important to convince drug companies to invest in PKCα for clinical development. β-receptor antagonists (and AngII pathway inhibitors) have been the mainstay of heart failure treatment protocols for the past 2 decades, a time span over which essentially nothing new has materialized to extend patient lifespan. At that same time an increasing number of pharmaceutical companies have dropped their heart failure research programs, or existing companies with heart failure programs have been reluctant to venture into this area. Reluctance here likely stems from a lack of adequate patent protection given extensive prior art in the heart failure literature, and given the bias/mentality that nothing new will feasibly challenge β-blockers, as well as the high expense occurred in conducting heart failure clinical trails. This collective mentality leaves a large unmet need, especially since β-blockers only mildly extend lifespan in heart failure [43]. PKCα is clearly one of the most attractive targets for clinical development of any current target suggested in the recent heart failure literature. Thus, as the data continues to amass, we question why pharmaceutical companies with an easy claim in this area are so reluctant to mobilize and conduct clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Fondation Leducq and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (J.D.M.). Q.L. was supported by a K99/R00 award from the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dorn GWII, Force T. Protein kinase cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:527–537. doi: 10.1172/JCI24178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.House C, Kemp BE. Protein kinase C contains a pseudosubstrate prototope in its regulatory domain. Science. 1987;238:1726–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.3686012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Churchill E, Budas G, Vallentin A, Koyanagi T, Mochly-Rosen D. PKC isozymes in chronic cardiac disease: possible therapeutic targets? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:569–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.121806.154902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabri A, Steinberg SF. Protein kinase C isoform-selective signals that lead to cardiac hypertrophy and the progression of heart failure. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;251:97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg M, Steinberg SF. Tissue-specific developmental regulation of protein kinase C isoforms. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51:1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hambleton M, Hahn H, Pleger ST, Kuhn MC, Klevitsky R, Carr AN, et al. Pharmacological- and gene therapy-based inhibition of protein kinase Calpha/beta enhances cardiac contractility and attenuates heart failure. Circulation. 2006;114:574–582. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pass JM, Gao J, Jones WK, Wead WB, Wu X, Zhang J, Baines CP, et al. Enhanced PKC beta II translocation and PKC beta II-RACK1 interactions in PKC epsilon-induced heart failure: a role for RACK1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2500–H2510. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ping P, Zhang J, Qiu Y, Tang XL, Manchikalapudi S, Cao X, et al. Ischemic preconditioning induces selective translocation of protein kinase C isoforms epsilon and eta in the heart of conscious rabbits without subcellular redistribution of total protein kinase C activity. Circ Res. 1997;81:404–414. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu X, Bishop SP. Increased protein kinase C and isozyme redistribution in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy in the rat. Circ Res. 1994;75:926–931. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.5.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jalili T, Takeishi Y, Song G, Ball NA, Howles G, Walsh RA. PKC translocation without changes in Galphaq and PLC-beta protein abundance in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;277:H2298–H2304. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.6.H2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Windt LJ, Lim HW, Haq S, Force T, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin promotes protein kinase C and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation in the heart. Cross-talk between cardiac hypertrophic signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13571–13579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayer AL, Heidkamp MC, Patel N, Porter M, Engman S, Samarel AM. Alterations in protein kinase C isoenzyme expression and autophosphorylation during progression of pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun MU, LaRosee P, Schon S, Borst MM, Strasser RH. Differential regulation of cardiac protein kinase C isozyme expression after aortic banding in rat. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:52–63. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Paradis P, Aries A, Komati H, Lefebvre C, Wang H, et al. Convergence of protein kinase C and JAK-STAT signaling on transcription factor GATA-4. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9829–9844. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.9829-9844.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simonis G, Briem SK, Schoen SP, Bock M, Marquetant R, Strasser RH. Protein kinase C in the human heart: differential regulation of the isoforms in aortic stenosis or dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;305:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9533-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowling N, Walsh RA, Song G, Estridge T, Sandusky GE, Fouts RL, et al. Increased protein kinase C activity and expression of Ca2þ-sensitive isoforms in the failing human heart. Circulation. 1999;99:384–391. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braz JC, Gregory K, Pathak A, Zhao W, Sahin B, Klevitsky R, et al. PKC-alpha regulates cardiac contractility and propensity toward heart failure. Nat Med. 2004;10:248–254. doi: 10.1038/nm1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn HS, Marreez Y, Odley A, Sterbling A, Yussman MG, Hilty KC, et al. Protein kinase Calpha negatively regulates systolic and diastolic function in pathological hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2003;93:1111–1119. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000105087.79373.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q, Chen X, Macdonnell SM, Kranias EG, Lorenz JN, Leitges M, et al. Protein kinase C{alpha}, but not PKC{beta} or PKC{gamma}, regulates contractility and heart failure susceptibility: implications for ruboxistaurin as a novel therapeutic approach. Circ Res. 2009;105:194–200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.195313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hambleton M, York A, Sargent MA, Kaiser RA, Lorenz JN, Robbins J, et al. Inducible and myocyte-specific inhibition of PKCalpha enhances cardiac contractility and protects against infarction-induced heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3768–H3771. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00486.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian R, Miao W, Spindler M, Javadpour MM, McKinney R, Bowman JC, et al. Long-term expression of protein kinase C in adult mouse hearts improves postischemic recovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13536–13541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong D, Cha H, Kim E, Kang M, Yang DK, Kim JM, et al. PICOT inhibits cardiac hypertrophy and enhances ventricular function and cardiomyocyte contractility. Circ Res. 2006;99:307–314. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000234780.06115.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorn GW, 2nd, Molkentin JD. Manipulating cardiac contractility in heart failure: data from mice and men. Circulation. 2004;109:150–158. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111581.15521.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhotra R, D'Souza KM, Staron ML, Birukov KG, Bodi I, Akhter SA. G alpha(q)-mediated activation of GRK2 by mechanical stretch in cardiac myocytes: the role of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13748–13760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Koch WJ. Genetic and phenotypic targeting of beta-adrenergic signaling in heart failure. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;263:5–9. doi: 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000041843.64809.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belin RJ, Sumandea MP, Allen EJ, Schoenfelt K, Wang H, Solaro RJ, et al. Augmented protein kinase C-alpha-induced myofilament protein phosphorylation contributes to myofilament dysfunction in experimental congestive heart failure. Circ Res. 2007;101:195–204. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sumandea MP, Pyle WG, Kobayashi T, de Tombe PP, Solaro RJ. Identification of a functionally critical protein kinase C phosphorylation residue of cardiac troponin T. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35135–35144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kooij V, Boontje N, Zaremba R, Jaquet K, dos Remedios C, Stienen GJ, et al. Protein kinase C alpha and epsilon phosphorylation of troponin and myosin binding protein C reduce Ca2+ sensitivity in human myocardium. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:289–300. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0053-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hidalgo C, Hudson B, Bogomolovas J, Zhu Y, Anderson B, Greaser M, et al. PKC phosphorylation of titin's PEVK element: a novel and conserved pathway for modulating myocardial stiffness. Circ Res. 2009;105:631–638. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang L, Wolska BM, Montgomery DE, Burkart EM, Buttrick PM, Solaro RJ. Increased contractility and altered Ca(2+) transients of mouse heart myocytes conditionally expressing PKCbeta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1114–C1120. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.5.C1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Grant JE, Doede CM, Sadayappan S, Robbins J, Walker JW. PKC-betaII sensitizes cardiac myofilaments to Ca2+ by phosphorylating troponin I on threonine-144. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:823–833. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Doshi D, Morrow J, Katchman A, Chen X, Marx SO. Protein kinase C isoforms differentially phosphorylate Ca(v)1.2 alpha(1c) Biochemistry. 2009;48:6674–6683. doi: 10.1021/bi900322a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sussman MA, Hamm-Alvarez SF, Vilalta PM, Welch S, Kedes L. Involvement of phosphorylation in doxorubicin-mediated myofibril degeneration. An immunofluorescence microscopy analysis. Circ Res. 1997;80:52–61. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palaniyandi SS, Sun L, Ferreira JC, Mochly-Rosen D. Protein kinase C in heart failure: a therapeutic target? Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:229–239. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konopatskaya O, Gilio K, Harper MT, Zhao Y, Cosemans JM, Karim ZA, et al. PKCalpha regulates platelet granule secretion and thrombus formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:399–407. doi: 10.1172/JCI34665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang GS, Kuyumcu-Martinez MN, Sarma S, Mathur N, Wehrens XH, Cooper TA. PKC inhibition ameliorates the cardiac phenotype in a mouse model of myotonic dystrophy type 1. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3797–3806. doi: 10.1172/JCI37976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The PKC-DRS Study Group. Effect of ruboxistaurin in patients with diabetic macular edema: thirty-month results of the randomized PKC-DMES clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:318–324. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jirousek MR, Gillig JR, Gonzalez CM, Heath WF, McDonald JH, 3rd, Neel DA, et al. (S)-13-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-10,11,14,15-tetrahydro-4,9:16, 21-dimetheno-1H, 13H-dibenzo[e,k]pyrrolo[3,4-h][1,4,13]oxadiazacyclohexadecene-1,3(2H)-d ione (LY333531) and related analogues: isozyme selective inhibitors of protein kinase C beta. J Med Chem. 1996;39:2664–2671. doi: 10.1021/jm950588y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyle AJ, Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Cox AJ, Gow RM, Way K, et al. Inhibition of protein kinase C reduces left ventricular fibrosis and dysfunction following myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kong L, Andrassy M, Chang JS, Huang C, Asai T, Szabolcs MJ, et al. PKCbeta modulates ischemia-reperfusion injury in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1862–H1870. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01346.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Connelly KA, Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Prior DL, Advani A, Cox AJ, et al. Inhibition of protein kinase C-beta by ruboxistaurin preserves cardiac function and reduces extracellular matrix production in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:129–137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.765750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skvara H, Dawid M, Kleyn E, Wolff B, Meingassner JG, Knight H, et al. The PKC inhibitor AEB071 may be a therapeutic option for psoriasis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3151–3159. doi: 10.1172/JCI35636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramani GV, Uber PA, Mehra MR. Chronic heart failure: contemporary diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:180–195. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]