Abstract

Purpose

Most stomach surgeons have been educated sufficiently in conventional open distal gastrectomy (ODG) but insufficiently in laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG). We compared learning curves and clinical outcomes between ODG and LADG by a single surgeon who had sufficient education of ODG and insufficient education of LADG.

Materials and Methods

ODG (90 patients, January through September, 2004) and LADG groups (90 patients, June 2006 to June 2007) were compared. The learning curve was assessed with the mean number of retrieved lymph nodes, operation time, and postoperative morbidity/mortality.

Results

Mean operation time was 168.3 minutes for ODG and 183.6 minutes for LADG. The mean number of retrieved lymph nodes was 37.9. Up to about the 20th to 25th cases, the slope decrease in the learning curve for LADG was more apparent than for ODG, although they both reached plateaus after the 50th cases. The mean number of retrieved lymph nodes reached the overall mean after the 30th and 40th cases for ODG and LADG, respectively. For ODG, complications were evenly distributed throughout the subgroups, whereas for LADG, complications occurred in 10 (33.3%) of the first 30 cases.

Conclusions

Compared with conventional ODG, LADG is feasible, in particular for a surgeon who has had much experience with conventional ODG, although LADG required more operative time, slightly more time to get adequately retrieved lymph nodes and more complications. However, there were more minor problems in the first 30 LADG than ODG cases. The unfavorable results for LADG can be overcome easily through an adequate training program for LADG.

Keywords: Laparoscopic, Gastrectomy, Learning curve

Introduction

Korea and Japan have the highest prevalence of gastric cancer in the world, and the detection rate of early gastric cancer (EGC) is high with the development of mass screening methods.(1) In particular, in cases of EGC located at the distal portion, laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG), a minimally invasive procedure, has many advantages over conventional open distal gastrectomy (ODG): less blood-loss, less inflammation, less postoperative pain, faster restoration of pulmonary function, faster flatus, earlier feeding, more shortened hospitalization day and smaller incision scar. (2-5) Since 2001 when a survey had reported that LADG was performed only in 5% of all gastrectomies in Japan,(6) LADG had been widely performed more and more due to its numerous advantages. Thus, many surgeons have practiced the operative technique of LADG.

However, because there are technical difficulties in LADG compared to ODG, surgeons need to overcome a learning curve. In particular, surgeons who have had much experience with conventional ODG wonder whether the learning curve of LADG is more difficult than it of ODG. Therefore, the present study was conducted to compare the learning curves and clinical outcomes between LADG and ODG that were performed by a single surgeon.

Materials and Methods

1. Patients

A single surgeon (CY Kim) participated in over 300 cases of ODG as a 1st assistant during his 2 years of fellowship at the gastrointestinal division of the Department of Surgery. The surgeon performed his first ODG in January of 2004, and there were 90 patients in the ODG group, who underwent ODG consecutively between January and September of 2004. He did his first LADG in June of 2006. The LADG group comprised 90 patients who underwent LADG consecutively between June, 2006 and June, 2007.

The LADG patients were limited to those that invaded the mucosa, submucosa or muscularis propria, without lymph node metastasis(7) on endoscopic ultrasonography or computerized tomography and those without concurrent malignant tumors in other organs or previous abdominal operation. The ODG patients who had resectable primary lesions and no distant metastasis by preoperative evaluations were enrolled.

2. Methods

The surgeon had no experience in participating in LADG as an assistant. But he prepared for LADG for 1 year through the observation of expert surgeons' operations, image training using videotapes and animal LADG on pigs. The point at which technical difficulties were overcome was defined as the point where the operation time reached its plateau. In addition, the learning curve was assessed regarding 2 aspects: proficiency in radical resection and postoperative morbidity and mortality. Since lymph node dissection is an important component of radical resection, the proficiency in radical resection was assessed with the mean number of retrieved lymph nodes of each sequential subgroups of 10 cases arbitrarily in both the ODG and LADG groups. Postoperative morbidity and mortality was checked in sequential subgroups of 30 cases because these events were non-continuous and relatively uncommon. Among postoperative complications, gastric stasis, pleural effusion and bleeding from the anastomosis site were defined as follows. Gastric stasis was defined as the situation where a patient had difficulty in passing food through the anastomosis site with subsequent retention of food material on simple abdominal X-rays and fasted for at least 1 day. Pleural effusion was defined as the situation where a patient was diagnosed with pleural effusion on simple chest X-rays and underwent interventions such as tube drainage or needle aspiration. Bleeding from the anastomosis site was defined as the situation where bleeding was identified at the anastomosis site by gastroduodenoscopy.

In cases where concomitant operations were performed, the operation time required for the concomitant operations was subtracted from the total operation time.

3. Operative techniques

All patients were placed in a supine position under general anesthesia.

4. LADG

At the day before operation, clipping was performed 2- to 3-cm proximal to the lesion through a gastroduodenoscopic approach in all patients. The operator and the camera assistant stood on the right and left side of the patient, respectively. For the pneumoperitoneum, a 1-cm incision was made at the midpoint of the imaginary line between the left anterosuperior iliac spine and umbilicus. A Veress needle was inserted into the peritoneal cavity. CO2 pneumoperitoneum was created at a pressure of 12 mmHg. A 10 mm trocar was inserted through the same incision and was used as a camera port. And second trocar for the surgeon's left hand (5 mm in diameter) 2 cm below the intersection of the right anterior axillary line and right subchondral line, third one for the surgeon's right hand (10 mm in diameter) 2- to 3-cm lateral to the umbilicus on the right side, fourth one for the assistant (10 mm in diameter) 1- to 2-cm distal to the intersection of the left axillary line and left subchondral line, and the last one (10 mm in diameter) 4- to 5-cm distal to the xiphoid process which was used for gastroduodenostomy and gastrojejunostomy by extending it 5 to 6 cm right laterally. Left and right partial omentectomy was performed using ultrasonically activated scissors (Harmonic Scalpel; Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) with ligation of left gastroepiploic vessels (No. 4sb), right gastroepiploic vessels (No. 4d) and infrapyloric lymph node (No. 6). After a suprapyloric lymph node (No. 5) and anterior to the hepatoduodenal ligament (No. 12a) dissection, the right gastric artery was identified and ligated. Lifting up again the posterior wall of the stomach antero-superiorly, No. 8a (the common hepatic artery), No. 9 (the celiac trunk) and No. 11p (the splenic artery) lymph nodes were removed en bloc, and then the left gastric vessels (No. 7) were ligated and divided. The lymph node dissection proceeded cephalad until the esophagogastric junction was reached (No. 1). For anastomosis, the trocar incision in the midline of the upper abdomen was extended 5~6 cm transversely toward the lateral side. The distal stomach including the primary tumor was transected using a linear stapler (Proximate linear cutter 100 mm; Ethicon, Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). The segment of the duodenum 1 to 2 cm below pyloric ring was transected. For Billroth I anastomosis, the anvil of a circular stapler (Proximate CDH29; Ethicon, Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) was inserted into the stump of the duodenum and the purse-string suture was done and tied. The body of the circular stapler was introduced into the remnant stomach through a 3- to 4-cm gastrotomy incision at greater curvature that was made 4- to 5-cm proximal to the stomach resection margin. After performing a stapling gastroduodenostomy at resection margin, greater curvature, gastrotomy incision in the remnant stomach was closed by an additional linear stapler (Proximate linear cutter 60 mm; Ethicon, OH, USA). For Billroth II anastomosis, the jejunum 10- to 20-cm distal to the Treitz ligament was anastomosed to the greater curvature using a linear stapler (Proximate linear cutter 60 mm; Ethicon, Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). No closed suction drains were placed.

5. ODG

Among ODG patients, those who were suspected of having EGC underwent clipping 2 to 3 cm proximal to the lesion through the gastroduodenoscopic approach at the day before operation.

An upper midline incision was made starting from the xiphoid process to the point below or above the level of the umbilicus. After opening the abdominal cavity, omentectomy was done like LADG. After completion of the omentectomy on the both side, the left gastroepiploic vessels (No. 4d & No. 4sb) and the right gastroepiploic vessels (No. 6) were ligated and divided, respectively. The duodenum was exposed up to 3 to 4 cm distal to the pylorus. Anterior to the hepatoduodenal ligament (No. 12a) and a suprapyloric lymph node (No. 5) dissection were done, and the right gastric vessels were ligated.

Unlike LADG, the segment of the duodenum 1 to 2 cm below pyloric ring was transected. And then No. 8a (the common hepatic artery), No. 9 (the celiac trunk) and No. 11p (the splenic artery) lymph nodes were removed en bloc, and then the left gastric vessels (No. 7) were ligated and divided. After No.1 lymph node dissection, the distal stomach was transected using a linear stapler (Proximate linear cutter 100 mm; Ethicon, Endo-Surgery Inc. OH, Cincinnati, USA). Like LADG, Billroth I or Billorth II anastomosis was performed in the same manner as LADG. No closed suction drains were placed.

6. Postoperative care

ODG patients started sips of water on the day of the first flatus, a liquid diet on the next day and a soft diet thereafter. LADG patients started sips of water on the second postoperative day according to our clinical pathway protocol, regardless of flatus, and were put on a liquid diet on the third postoperative day and a soft diet on the fourth postoperative day. All patients were recommended to be discharged from the hospital on the seventh postoperative day. The time to the first flatus, time to initiation of oral feeding and hospitalization days were not compared between ODG and LADG patients because of the difference in the postoperative feeding schedule for them. Blood transfusion was considered when the hemoglobin level was below 8.0 g/dl.

1) Statistical analysis

The relationship between continuous variables was assessed by using the Student t test and ANOVA. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. To evaluate the learning curve according to operation time, the operation time was plotted for each group. A plateau phase was estimated from the moving average plotted on the scattergram by using the Loess fit method. All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

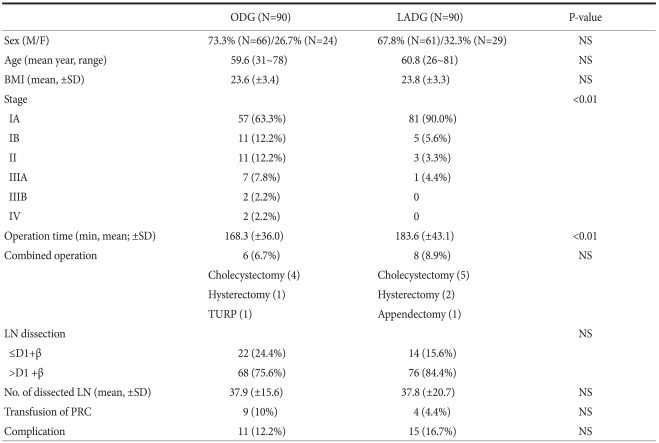

The mean age of the 180 patients was 60.2 years. There were 127 males (70.6%) and 53 females (29.4%). The mean body mass index (BMI) was 23.7 (ODG; 23.6 vs. LADG; 23.8). The mean operation time was 174.9 minutes (ODG; 168.3 vs. LADG; 183.6). The mean number of retrieved lymph nodes was 37.9 (ODG; 37.9 vs. LADG; 37.8). The demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes are shown in Table 1. The mean operation time was 168.3 minutes for ODG and 183.6 minutes for LADG and the difference was statistically significant (P=0.007). There were no significant differences between the ODG and LADG groups in the frequency of combined operation, the extent of lymphadenectomy, the number of retrieved lymph nodes, transfusion requirement and the frequency of complications.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes between LADG and ODG group

LADG = laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy; ODG = open distal gastrectomy; M = male; F = female; NS = not significant; BMI = body mass index; TURP = transurethral resection of prostate; LN = lymph node; PRC = packed red cell.

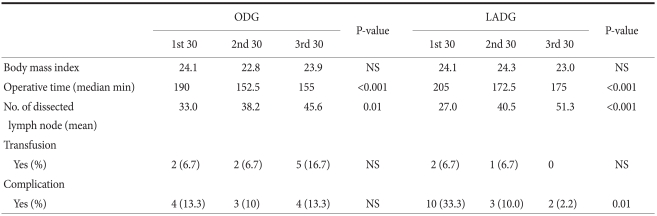

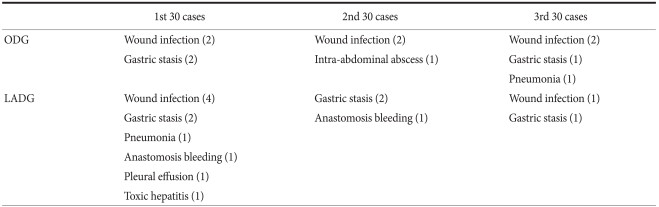

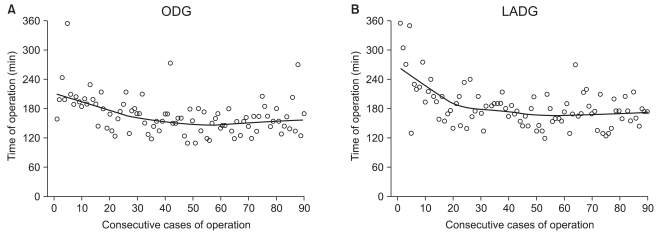

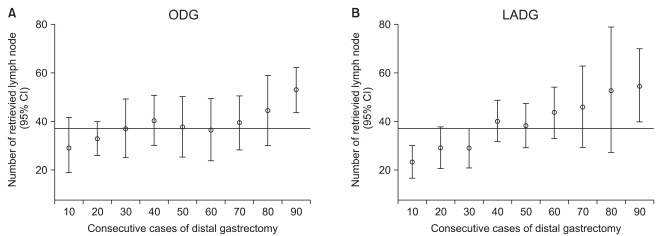

For ODG and LADG, the operation time, the mean number of retrieved lymph nodes, transfusion requirement and the frequency of complications were assessed in subgroups of 30 cases (Table 2). The operation time was significantly longer in the first 30 cases for both ODG and LADG. The overall morbidity rate was 12.2% for ODG and 16.7% for LADG, but the difference was not statistically significant. For ODG, complications were evenly distributed through the subgroups, whereas for LADG, complications occurred in 10 (33.3%) of the first 30 cases although they were not serious. Overall, complications occurred in a total of 26 cases (14.4%), but there were no serious complications or deaths (Table 3). There were no conversions to ODG in LADG patients. Fig. 1 shows the learning curve according to operation time. Up to early 20th cases, slope decrease in LADG is more apparent than in ODG, although they were reached its plateau after 50th cases. The mean number of retrieved lymph nodes reached the overall mean after 30th and 40th cases for ODG and LADG, respectively (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical outcomes between the LADG and ODG groups by 30 cases

LADG = laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy; ODG = open distal gastrectomy; NS = not significant.

Table 3.

Comparison of complications between the LADG and ODG groups by 30 cases

LADG = laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy; ODG = open distal gastrectomy.

Fig. 1.

Operative time is displayed as a scatterplot and plotted a best fit line using the Loess fit method. The weight function used in the Loess method is the tricube weight function. The line shows the learning curve. (A) For ODG, the operation time decreased slightly after the second 10 ODGs and reached its plateau after the fifth 10 ODGs. (B) For LADG, the operation time decreased abruptly up to the second 10 LADGs and reached its plateau after the fifth 10 LADGs. ODG = open distal gastrectomy; LADG = laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy.

Fig. 2.

Overall, the mean number of retrieved lymph nodes (mean±SD) was 37.9 (±15.6) in the ODG group and 37.8 (±20.7) in the LADG group. The mean number of retrieved lymph nodes in the sequential subgroups of 10 procedures reached the overall mean after the third 10 procedures for ODG and after the fourth 10 procedures for LADG. CI = confidence interval; ODG = open distal gastrectomy; LADG = laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy.

Discussion

The patterns of overcome a learning curve vary among surgeons. The differences depend on the surgeon's native ability, prerequisite educational program, previous experience with other surgeries, hospital volume, motivation for a new surgical procedure, patient characteristics, stable members of the surgical team and the support of the surgeon's institution.(8) The operation time is a representative tool for assessing a learning curve because it represents various components for learning a new technique. The operation time rapidly decreases at the initial period, becomes progressively flat and reaches its plateau (the point at which proficiency is reached).(9) In addition, from an oncologic viewpoint, the additional indicators are competence in radical resection and postoperative complications.

Although there have been relatively well training programs for conventional gastrectomy during residency and fellowship, there have been few data on the learning curves of ODG. Numerous studies have recently reported that the learning curve of LADG can be completed without difficulties although this is a new operative technique. It has been demonstrated that the number of cases required to achieve competence in LADG is 30th to 60th cases.(10,11) In the present study, the operation time of LADG was more prolonged at the beginning than ODG, but more decreased abruptly and reached a lower slope phase after the 20th LADGs than after 20th ODG. The operation time reached its plateau after the 50th procedures in the ODG and LADG groups. Kim et al.(10) observed this turning point after the 10th and another plateau after the 50th LADGs which were designated the first and second stable period, respectively. In the present study, the first and second stable period was more apparent in the LADG than in the ODG.

The number of retrieved lymph nodes is an excellent indicator for assessing proficiency in radical resection. In our study, there was no significant difference in the overall number of retrieved lymph nodes between the ODG and LADG groups. Until the 20th ODG and 30th LADG, the mean number of retrieved lymph nodes did not reach the overall mean in neither group. Previous studies reported that the number was achieved insufficiently in the learning curve of LADG.(11-13) In the present study, the mean number reached the overall mean number after the 30th ODGs and after the 40th LADGs, implying that the stable number of retrieved lymph nodes was reached faster in the ODG group than in the LADG group. This result may be attributed to the more assistant experience with ODG.

Not only the operation time is shortened and the competence of radical resection is achieved, but also patient's safety should be considered. Thus, it has been advocated that learning curve should be assessed by using various indicators such as the conversion rate to ODG, kind and frequency of complications and the mortality rate.(14-16) In the present study, no serious postoperative complications, deaths or conversion to ODG was noted. Postoperative complications occurred evenly in the ODG group throughout the experiment, whereas they occurred mainly after the first 30th cases in the LADG group. This result reflects the prior adequate training in ODG and technical difficulties in LADG. A previous study has indicated that patient's safety may be affected by a high frequency of postoperative complications at the early period due to technical difficulties in LADG.(13)

In conclusion, the LADG compared with conventional ODG is feasible, in particular to the surgeon who has had much experience with conventional ODG although the LADG had more operative time, slightly more time to get the adequate retrieved lymph nodes and more complication however that was minor problem in the 30th cases than the ODG. The unfavorable results of LADG could be overcome easily through an adequate training program for LADG.

References

- 1.Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:354–362. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goh PM, Alponat A, Mak K, Kum CK. Early international results of laparoscopic gastrectomies. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:650–652. doi: 10.1007/s004649900413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Shiromizu A, Bandoh T, Aramaki M, Kitano S. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy compared with conventional open gastrectomy. Arch Surg. 2000;135:806–810. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.7.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Etoh T, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for cancer. Dig Dis. 2005;23:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000088592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y. A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery. 2002;131(1 suppl):S306–S311. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.120115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitano S, Bandoh T, Kawano K. Endoscopic surgery in Japan. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2001;10:215–219. doi: 10.1080/136457001753334620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sobin LH, Wittekind C, editors. International Union Against Cancer (UICC): TNM Classification of Malignant Tumor. 6th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachdeva AK, Russell TR. Safe introduction of new procedures and emerging technologies in surgery: education, credentialing, and privileging. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt RA, Lee T, editors. Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis. 4th ed. Champaign, Human Kinetics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim MC, Jung GJ, Kim HH. Learning curve of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with systemic lymphadenectomy for early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7508–7511. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i47.7508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JH, Jung YS, Kim BS, Jeong O, Lim JT, Yook JH, et al. Learning curve of a laparoscopy assisted distal gastrectomy for a surgeon expert in performing a conventional open gastrectomy. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2006;6:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KC, Yook JH, Choi JE, Cheong O, Lim JT, Oh ST, et al. The Learning Curve of Laparoscopy-assisted Distal Gastrectomy (LADG) for cancer. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2008;8:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo CH, Kim HO, Hwang SI, Son BH, Shin JH, Kim H. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer during a surgeon's learning curve period. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2250–2257. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin SH, Kim DY, Kim H, Jeong IH, Kim MW, Cho YK, et al. Multidimensional learning curve in laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:28–33. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinçler S, Koller MT, Steurer J, Bachmann LM, Christen D, Buchmann P. Multidimensional analysis of learning curves in laparoscopic sigmoid resection: eight-year results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1371–1378. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6752-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes TL. A cumulative analysis of an individual surgeon's early experience with elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Am J Surg. 2005;189:469–473. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]