Summary

The nuclear protein Cyclophilin 33 (Cyp33) is a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase that catalyzes cis-trans isomerization of the peptide bond preceding a proline and promotes folding and conformational changes in folded and unfolded proteins. The N-terminal RRM domain of Cyp33 has been found to associate with the third plant homeodomain (PHD3) finger of the Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) proto-oncoprotein and a poly-A RNA sequence. Here, we report a 1.9 Å resolution crystal structure of the RRM domain of Cyp33 and describe the molecular mechanism of PHD3 and RNA recognition. The Cyp33 RRM domain folds into a five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet and two α-helices. The RRM domain but not the catalytic module of Cyp33 binds strongly to PHD3, exhibiting a 2 μM affinity as measured by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). NMR chemical shift perturbation (CSP) analysis and dynamics data reveal that the β strands and the β2–β3 loop of the RRM domain are involved in the interaction with PHD3. Mutations in the PHD3-binding site or deletions in the β 2/β 3 loop lead to a significantly reduced affinity or abrogation of the interaction. The RNA-binding pocket of the Cyp33 RRM domain, mapped based on NMR CSP and mutagenesis, partially overlaps with the PHD3-binding site, and RNA association is abolished in the presence of MLL PHD3. Full-length Cyp33 acts as a negative regulator of MLL-induced transcription and reduces the expression levels of MLL target genes MEIS1 and HOXA9. Together, these in vitro and in vivo data provide insight into the multiple functions of Cyp33 RRM and suggest a Cyp33-dependent mechanism for regulating the transcriptional activity of MLL.

Keywords: RRM domain, PHD finger, Cyp33, MLL, mechanism, structure

Introduction

The nuclear Cyclophilin 33 (Cyp33) was initially identified in human Jurkat T cells in 1996 1. It belongs to a highly conserved family of PPIases that catalyze cis-trans isomerization of the peptide bond preceding a proline, accelerating folding and stimulating conformational changes in folded and unfolded proteins 2. The PPIase activity is also essential for intracellular protein transport and transient protein interactions involving Cyps and can be effectively inhibited by cyclosporine A 1; 3. The catalytic CYP/PPIase domain of Cyp33 is located in the carboxy-terminal region of the protein and is preceded by an amino-terminal RNA-recognition motif (RRM), also known as RNA-binding domain (RBD) or ribonucleoprotein (RNP). Although it remains unclear whether the Cyp33 RRM domain directly interacts with RNA, the full length Cyp33 protein has been shown to preferentially associate with mRNAs containing an AAUAAA sequence or a poly-A tail, and this association appears to activate the PPIase activity of Cyp33 1; 4. Recent reports have also implicated the RRM domain in binding to the third plant homeodomain (PHD3) finger of MLL (myeloid/lymphoid or mixed lineage leukemia) 5; 6. This interaction has been proposed to switch the MLL function from transactivation to repression 6, however how the RRM domain recognizes the MLL PHD3 finger remains unclear.

MLL is a member of the trithorax protein family that regulates gene expression, particularly HOX genes, during embryonic development. MLL is translocated or mutated in a variety of aggressive human blood cancers including acute lymphoblastic and acute myelogenous leukemias 7; 8. This large, ~4,000-residue protein contains numerous functional modules including three amino-terminal DNA-binding AT hook domains, specific for AT-rich regions of the DNA minor groove, two speckled nuclear localization signals, and a transcriptional repression region containing a CXXC zinc-finger homologous to the CpG-binding domain of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) 9; 10; 11. Three sequential PHD modules, an acetyl-lysine binding bromodomain and another atypical PHD finger precede a transactivation (TA) domain. The TA region has a docking site for CREB-binding protein (CBP), a histone acetyltransferase (HAT) able to acetylate histone H3 and H4 at the HOX area 12. The carboxy-terminal Su(var)3–9, Enhancer of Zeste, Trithorax (SET) domain shows histone methyltransferase (HMTase) activity with a high specificity for lysine 4 of H3 13; 14; 15. Named after the first yeast H3K4 HMTase Set1, it is highly conserved throughout the SET domain-containing proteins and is capable of producing mono-, di- and tri-methylated H3K4 marks 16. A short sequence preceding the SET domain is recognized by WDR5 17; 18; 19. As many other HMTases, MLL is a component of a larger nuclear complex that also contains WDR5, RbPB5 and ASH2, all of which are required for the functional assembly, chromatin targeting and enzymatic activity of the MLL complex (also referred to as the human COMPASS) 20.

The three sequential PHD fingers in MLL, which are deleted in oncogenic translocation chimeras, comprise one of the most conserved regions of MLL. Although the biological role of this region remains elusive, it has recently been shown that the second PHD finger (PHD2) is involved in dimerization, whereas PHD3 binds the Cyp33 RRM domain 5; 6; 21. The PHD finger region appears to play a regulatory role in MLL function and suppresses MLL-mediated leukaemogenesis. Inclusion of the PHD2-PHD3 fingers in the chimeric MLL-AF9 protein inhibits transformation of mouse bone marrow and leads to hematopoietic cell differentiation 22. Insertion of PHD3 into the MLL-ENL chimera suppresses MLL-ENL-induced immortalization of murine bone marrow progenitor cells 6. Clearly PHD3 is essential for the proper function of MLL, yet the molecular basis underlying its biological activities including the association with Cyp33 RRM is unknown.

In this study, we characterize binding of the RRM domain of Cyp33 to the PHD3 finger of MLL and demonstrate that this interaction abolishes the association of RRM with RNA. The crystal structure of the Cyp33 RRM domain determined at 1.9 Å resolution, a combination of NMR binding and dynamics data, mutagenesis, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measurements and in vivo quantitative RT-PCR assays were used to elucidate the molecular mechanism of the Cyp33-MLL association. Our findings suggest a negative regulatory role of this interaction in transcription of MLL target genes.

Results and Discussion

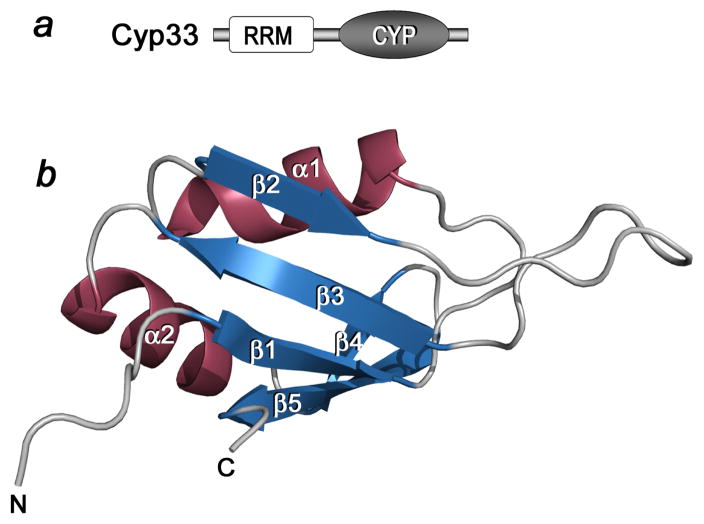

Overall structure of the Cyp33 RRM domain

The structure of the RRM domain of human Cyp33 (residues 1–83) was determined at 1.9 Å resolution by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 1). The RRM domain folds into a five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet and two α-helices. The α1 helix is positioned between the β 1 and β 2 strands whereas helix α2 connects strands β 3 and β 4. The β 1 strand (residues V7-G11), α1 helix (residues D19-F26), β 2 strand (residues T33-Q36), β 3 strand (residues F49-F54), α2 helix (residues A57-M67) and β 5 strand (residues R75-L81) adopt a canonical β αβ β αβ RRM fold with an additional strand (β 4, residues E69-L72) pairing with the β 5 strand and forming the edge of the β sheet. Notably, residues located in the long β2–β3 loop and β2 and β3 strands, that is, D34, I35, I37, L39, D40, E42, T43, E44, H46, R47, F49, V52, and F54 exhibited the largest chemical shift changes upon binding to PHD3 and residues of the β1 and β5 strands were perturbed to a lesser degree (Fig. 3a, b, and d). These data suggest that the β2–β3 loop and the β strands of the Cyp33 RRM domain are directly or indirectly involved in the interaction with the PHD3 finger of MLL.

Figure 1.

The crystal structure of the RRM domain of Cyp33 determined at 1.85 Å resolution. (a) Architecture of Cyp33: the amino-terminal RRM domain and the catalytic CYP domain. (b) Ribbon diagram of the RRM structure.

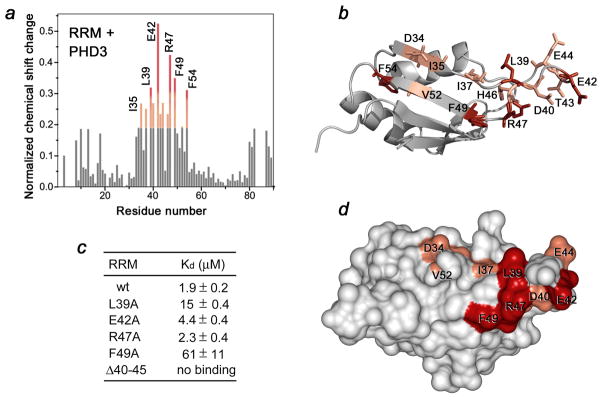

Figure 3.

The MLL PHD3-binding site of the Cyp33 RRM domain. (a) A histogram shows normalized 1H,15N chemical shift changes in backbone amides of 15N-labeled RRM upon addition of unlabeled PHD3 at a protein ratio of 1:1. (b, d) Residues that exhibit significant PHD3-induced resonance perturbations in (a) are mapped on the ribbon diagram (b) and the surface (d) of the Cyp33 RRM domain. Colored bars indicate significant change being greater than an average plus one standard deviation. (c) The binding affinities of wild type Cyp33 RRM and mutants for MLL PHD3, as measured by ITC. Interaction of the RRMΔ40–45 mutant was examined by NMR. Other mutants generated, including G48A, F54A, RRMΔ41–42, RRMΔ41–43 and RRMΔ40–43, precipitated during dialysis for ITC experiments.

The Cyp33 RRM domain binds strongly to the PHD3 finger of MLL

To determine the role of the most perturbed residues of the Cyp33 RRM domain, we replaced them with alanine and, additionally, generated mutants with partially truncated β2–β3 loop. Binding of the mutant proteins to PHD3 was examined by ITC and NMR. Deletion of the β2–β3 loop in RRMΔ40–45 completely abolished the interaction, whereas mutation of F49 and L39 reduced the binding affinity of the RRM domain for the PHD3 finger by 35- and 10-fold, respectively, suggesting a significant contribution of hydrophobic contacts (Fig. 3c). The E42A and R47A mutants bound only slightly weaker than the wild-type protein. Together, these results demonstrate that the residues located in the β2–β3 loop and the β strands constitute the binding interface of the Cyp33 RRM domain (Fig. 3b and d).

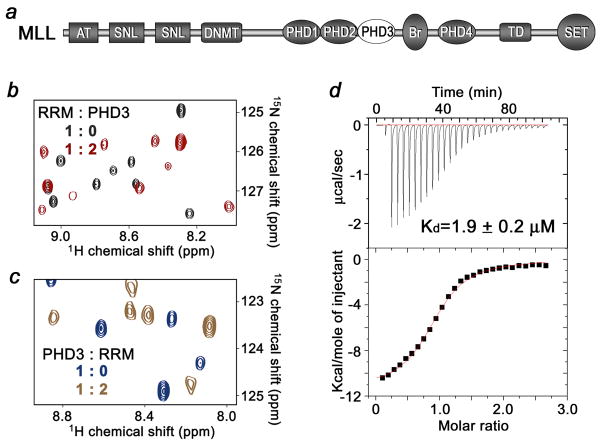

To determine the strength of the RRM-PHD3 interaction, the dissociation constant and thermodynamic parameters were measured by ITC (Fig. 2d). The Kd value was found to be 1.9 ± 0.2 μM, and is in agreement with the pattern of resonance perturbations in the NMR titration experiments. The interaction was enthalpy driven (ΔH = −10 ± 0.5 kcal), and a negative change in entropy (ΔS = −9 ± 2 cal mol−1 K−1) indicated that the proteins lost some conformational freedom upon formation of the complex.

Figure 2.

Binding of the RRM domain of Cyp33 to the PHD3 finger of MLL. (a) Schematic of MLL. The PHD3 finger is shown as a white oval. (b) Superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the 15N-labeled Cyp33 RRM domain, collected in the absence and presence of a two-fold excess of unlabeled MLL PHD3. (c) Superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the 15N-labeled MLL PHD3 finger, collected in the absence and presence of a two-fold excess of unlabeled Cyp33 RRM. (c) Representative ITC curves used to calculate the binding affinity for the interaction between the Cyp33 RRM domain and the MLL PHD3 finger.

Identification of the PHD3-binding site of the Cyp33 RRM domain

To identify the active-site residues of the RRM domain, we assigned the 1H, 13C and 15N resonances of the ligand-free and PHD3-bound protein using a set of triple-resonance NMR experiments. The spectra were collected on 15N/13C-labeled RRM in the apo state and in complex with unlabeled PHD3. Shown in Fig. 3a is a histogram plot of the differences in chemical shifts for backbone amides of the RRM domain in the unbound and PHD3-bound states. Notably, residues located in the long β2–β 3 loop and β2 and β3 strands, that is, D34, I35, I37, L39, D40, E42, T43, E44, H46, R47, F49, V52, and F54 exhibited the largest chemical shift changes upon binding to PHD3 and residues of the β1 and β5 strands were perturbed to a lesser degree (Fig. 3a, b, and d). These data suggest that the β2–β3 loop and the β strands of the Cyp33 RRM domain are directly or indirectly involved in the interaction with the PHD3 finger of MLL.

To determine the role of the most perturbed residues of the Cyp33RRM domain, we replaced them with alanine and, additionally, generated mutants with partially truncated β2–β3 loop. Binding of the mutant proteins to PHD3 was examined by ITC and NMR. Deletion of the β2–β3 loop in RRMΔ40–45 completely abolished the interaction, whereas mutation of F49 and L39 reduced the binding affinity of the RRM domain for the PHD3 finger by 35- and 10-fold, respectively, suggesting a significant contribution of hydrophobic contacts (Fig. 3c). The E42A and R47A mutants bound only slightly weaker than the wild-type protein. Together, these results demonstrate that the residues located in the β2–β3 loop and the β strands constitute the binding interface of the Cyp33 RRM domain (Fig. 3b and d).

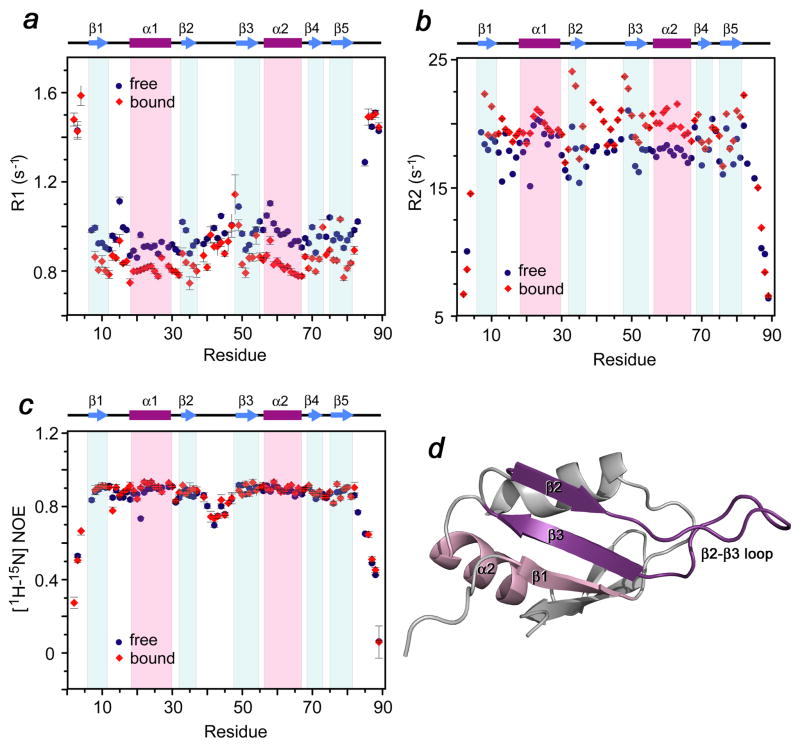

Binding of PHD3 induces changes in the dynamics of the β 2/β 3 loop, the β 1, β 2 and β 3 strands and the α2 helix of the Cyp33 RRM domain

The effect of the association with PHD3 on the dynamics of the RRM domain was investigated using 15N NMR relaxation experiments carried out in the absence and presence of the MLL PHD3 finger (Fig. 4). Comparison of the average relaxation rates in the ligand-free and PHD3-bound RRM domain suggested a global stabilization of the RRM structure in the complex. Binding to PHD3 caused a decrease of R1 values and an increase in R2 values for the majority of the RRM residues. The most evident changes in the R1 and R2 relaxation rates were observed for residues that are located in the β 2/β 3 loop, the β 1, β 2 and β 3 strands and the α2 helix, particularly those that are involved in the interaction with the PHD3 finger. The lack of changes in the heteronuclear NOE values indicated that the local internal backbone mobility on a sub-nanosecond timescale does not change due to the complex formation. The significantly larger R2 relaxation rates observed for some residues in the β 1, β 2 and β 3 strands pointed to a contribution from μs-ms dynamics in these regions of the complex. In agreement with the negative change in entropy, the dynamics data suggest that overall the RRM domain of Cyp33 becomes more rigid upon binding to the PHD3 finger.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of the Cyp33 RRM domain bound and unbound. (a–c) Relaxation parameters of the RRM domain in the absence (blue) and the presence (red) of a 1.5-fold excess of MLL PHD3. R1, R2 and NOE values were determined for backbone amide groups and are plotted for each residue of the Cyp33 RRM domain. The RRM secondary structure is shown above the graphs. (d) The most affected (due to the interaction with PHD3) residues of Cyp33 RRM are colored in shades of purple in the ribbon diagram of the RRM structure.

The human Cyp33 RRM domain is specific for MLL and does not interact with other PHD fingers

To determine whether Cyp33 RRM is able to recognize any PHD-finger fold, 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the 15N-labeled RRM domain were recorded as the unlabeled PHD module of tumor suppressor ING1 was titrated into the NMR sample (Supplementary Fig. 2). The amino acid sequence of the ING1 PHD finger contains a number of conserved (within the PHD family, including MLL PHD3) residues 24; 25. Addition of a five-fold excess of ING1 PHD did not induce chemical shift changes in the NMR spectrum of RRM, implying that there is no interaction between these two proteins. Thus, binding of the Cyp33 RRM domain to the MLL PHD3 finger is specific.

We next tested the ability of other RRM domains to recognize the MLL PHD3 finger. Addition of a 5-fold excess of unlabeled Drosophila Cyp33 RRM to the 15N-labeled MLL PHD3 finger or conversely, addition of a 5-fold excess of unlabeled MLL PHD3 to the 15N-labeled Drosophila Cyp33 RRM caused negligible changes in 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the proteins (Supplementary Fig. 3 and data not shown), revealing high specificity of human Cyp33 RRM toward human MLL PHD3.

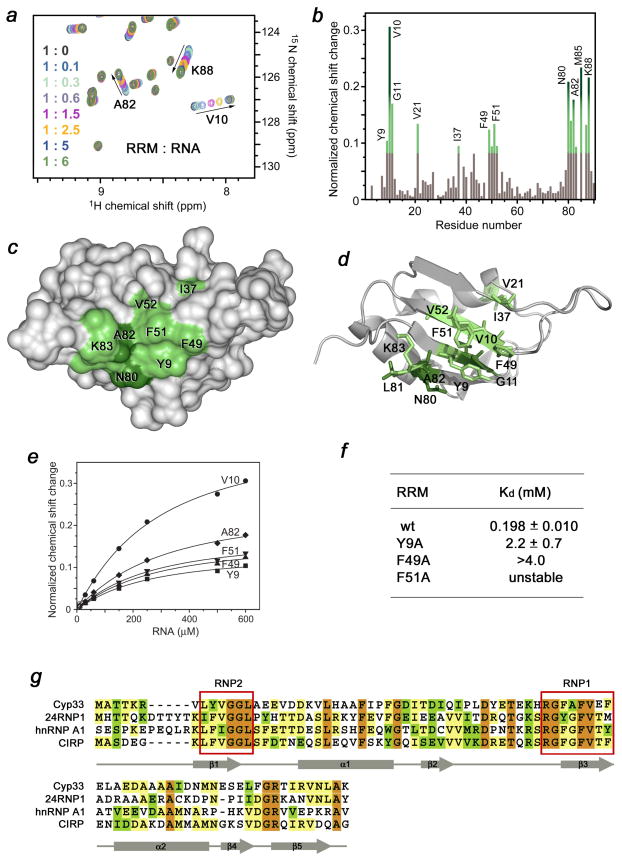

The Cyp33 RRM domain binds RNA

It has recently been shown that the full length Cyp33 protein associates with polyribonucleotide poly-A and poly-U but not with poly-G or poly-C, particularly preferring mRNA that contains the AAUAAA sequence 1; 4. To test whether the RRM domain of Cyp33 is responsible for this association, the AAUAAA RNA was synthesized and used in 1H,15N HSQC titration experiments (Fig. 5). Large chemical shift changes in the NMR spectra of 15N-labeled RRM, caused by the gradual addition of RNA, indicated that the Cyp33 RRM domain directly binds the RNA sequence. The residues of RRM located in the β 1 strand (Y9, V10, G11), β 3 strand (F49, A50, F51, V52), β 5 strand (N80, L81, A82) and in the C-terminus (M85-K88) were perturbed most significantly (Fig. 5b). These residues form an extended RNA-binding site that spreads across the β-sheet surface (Fig. 5c, d). The β-sheet is commonly used by other RRM modules in the interaction with single-stranded RNA 26; 27. In fact, the perturbed residues of the Cyp33 RRM domain comprise the two conserved ribonucleoprotein (RNP) motifs RNP2 (YVGGL-13) and RNP1 (RGFAFVEF-54) (Fig. 5g), that are required for RNA recognition by a typical RRM domain 26; 27. The aromatic side chains of Y9 in RNP2 and of F49 and F51 in RNP1 that protrude orthogonally to the protein surface are ideally positioned to form stacking interactions with RNA bases (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5.

The RNA-binding site of the Cyp33 RRM domain. (a) Eight superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of 0.1 mM Cyp33 RRM, collected as the AAUAAA RNA construct was gradually added. The spectra are color-coded according to the molar protein-RNA ratio (inset). (b) A histogram shows normalized 1H,15N chemical shift changes in backbone amides of 15N-labeled RRM (aa 1–90) upon addition of a six-fold excess of AAUAAA. (c, d) Residues that exhibit significant RNA-induced resonance perturbations in (b) are labeled and colored in shades of green on the ribbon diagram of the structure (c) and on the surface (d) of the Cyp33 RRM domain (aa 1–83). Colored bars indicate significant change being greater than an average plus one and a half standard deviation. (e) Representative binding curves used to determine the Kd values of the Cyp33 RRM-RNA interaction by NMR spectroscopy. (f) The RNA binding affinities of the wild type and mutant RRM domain measured by NMR. (g) Alignment of the RRM domain sequences of human proteins: absolutely, moderately and weakly conserved residues are colored brown, green and yellow respectively. The RNP2 and RNP1 motifs required for the interaction with RNA are outlined by red rectangles. The secondary structure of the Cyp33 RRM domain is shown below the sequences.

The binding affinity of the Cyp33 RRM domain for AAUAAA (Kd = 198 ± 11 μM) was obtained by plotting normalized chemical shift changes in the amide groups of the protein versus the RNA concentration (Fig. 5e). Although in general RRM domains exhibit a broad range of affinities for RNAs down to the low μM range 26; 28; 29, we point out that future studies are necessary to establish the significance of the RNA association by the Cyp33 RRM domain.

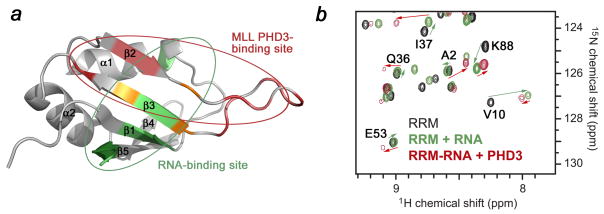

Interaction between Cyp33 RRM and MLL PHD3 disrupts the association of RRM with RNA

The binding sites of the Cyp33 RRM domain for PHD3 and RNA partially overlap (Fig. 6a), suggesting competitive binding. Indeed, when the MLL PHD3 finger was added to the Cyp33 RRM-RNA complex, the NMR resonances of RNA-bound RRM disappeared and resonances of the PHD3-bound protein appeared (Fig. 6b). The resulting 1H,15N HSQC spectrum was almost identical to that of the RRM domain obtained upon addition of PHD3 alone, implying that the presence of RNA does not alter the PHD3-binding mode of the Cyp33 RRM domain. Because the binding affinity of the RRM domain for the MLL PHD3 finger is ~100 fold higher than for the AAUAAA sequence, the PHD3 finger readily displaces the RNA.

Figure 6.

The MLL PHD3-binding site and the RNA-binding site of the Cyp33 RRM domain partially overlap. (a) The Cyp33 RRM domain is shown as a ribbon diagram. Residues of RRM that are perturbed by either PHD3, RNA or both ligands are colored red, green and yellow, respectively. The MLL PHD3-binding site and the RNA-binding site of the Cyp33 RRM domain are indicated by red and green circles, respectively. (b) Superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the Cyp33 RRM domain (0.1 mM) in the ligand-free form (black), after addition of 0.6 mM RNA (green), and after subsequent addition of 0.25 mM MLL PHD3 (red).

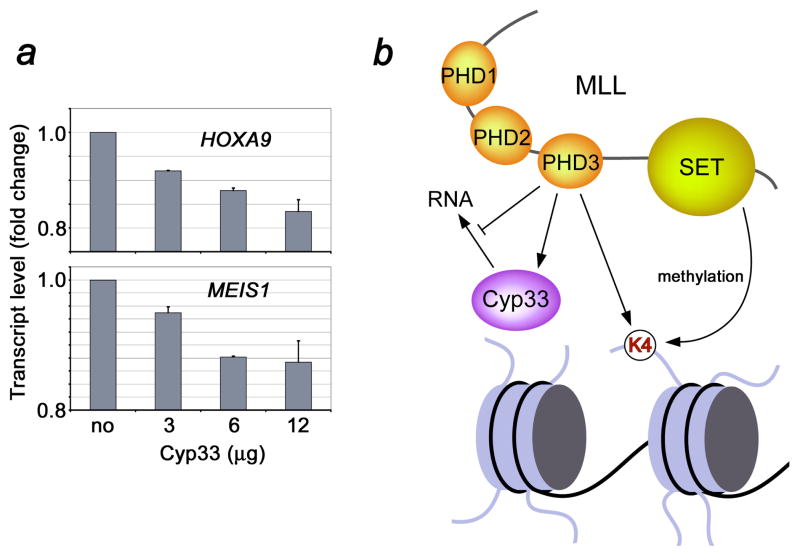

Cyp33 decreases expression levels of MLL target genes

MLL regulates expression of HOX and MEIS1 genes. We therefore examined the effect of Cyp33 overexpression on endogenous MLL-mediated gene transcription. 293T cells were transfected with different doses of FLAG-HIS6-CYP33 (3–12 μg), and after two days RNA was prepared and reverse-transcribed. HOXA9, MEIS1 and MLL expression levels were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 7a, Cyp33 transfection led to a decrease in the HOXA9 and MEIS1 expression levels, and this decrease was consistently greater with increasing doses of transfected Cyp33. Thus, these data suggest that Cyp33 negatively regulates the transcriptional function of MLL.

Figure 7.

Cyp33 decreases MLL-dependent gene transcription. Gene expression levels were quantified in transfected 293T cells using quantitative real-time RT-PCR (a). (b) A model of the Cyp33-MLL association.

In conclusion, our results reveal a pivotal role of the Cyp33 RRM-MLL PHD3 interaction in the function of MLL and Cyp33. The strong binding of the Cyp33 RRM domain to the MLL PHD3 finger disrupts association of RRM with RNA and in vivo data indicate that Cyp33 acts as a negative regulator of transcriptional activity of MLL, reducing the expression levels of MLL target genes (Fig. 7b). Although the mechanistic details of the negative regulation by Cyp33 remain to be determined, recent studies suggest several possible mechanisms. As we report in the accompanying paper, the MLL PHD3 finger also recognizes histone H3 trimethylated at Lys4 (H3K4me3), and this interaction is essential for MLL-dependent gene transcription. Binding of the Cyp33 RRM domain to MLL PHD3 could reduce the association of PHD3 with H3K4me3 and lead to the decrease of the target gene expression. Alternatively, the RRM-PHD3 interaction may bridge the catalytic PPIase domain of Cyp33 to MLL for the subsequent action on nearby regions of MLL or MLL-effectors, such as HDAC1, binding of which to the MLL repression region is known to be enhanced by Cyp33 5; 21. Other modules of MLL surrounding PHD3, including the adjacent PHD1 and PHD2 fingers and a bromodomain could further influence the binding activity of PHD3 and fine-tune transcriptional function of MLL. In summary, the molecular and structural details of the PHD3 and RNA recognition by the Cyp33 RRM domain described in this study provide new insights into the regulation of a cancer-critical protein by a cyclophilin.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

The pET-28 LIC vector containing DNA encoding residues 1–90 of human Cyp33 was modified to express His-tagged RRM. A shorter construct of Cyp33 RRM (residues 1–83) was generated by PCR. The unlabeled, 15N-labeled and 15N/13C-labeled proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) in LB or minimal media supplemented with 15NH4Cl or 15NH4Cl/13C6-glucose (Isotec). The bacterial cells were grown at 37 oC to an OD600 of 0.8 and protein expression was induced with 1.0 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37 °C for 5 hours. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 g, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% NP-40 and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche)) and lysed by sonication. The proteins were purified on a TALON affinity resin using a wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol (ME)) and eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCL pH 8.0 buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM ME and 150 mM imidazole. The His tag was cleaved with thrombin. The cleaved proteins were concentrated in Millipore concentrators (Millipore) and further purified by FPLC on a superdex 75 HR16/60 column in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8 buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The same protocol was used for expression and purification of the mutant proteins.

The PHD3 finger of MLL (residues 1565–1627) was subcloned into a pGEX-2T vector (Amersham). The unlabeled and 15N-labeled PHD3 finger was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) pLysS cells and purified as described in the accompanying manuscript. The unlabeled catalytic domain of human Cyp33 and unlabeled and 15N-labeled Drosophila Cyp33 RRM were expressed and purified using the same procedure described above for the human Cyp33 RRM domain. The unlabeled human ING1 PHD finger was purified as in 25.

X-ray crystallography

Crystallization of the human Cyp33 RRM domain (residues 1–83) was performed using a microcapillary technique 30. The crystals were obtained at 18 °C in 0.1 M Hepes and 1.0 M tri-sodium dehydrate citrate at pH 7.6. All crystals grew in a monoclinic space group (C2) with unit cell parameters of a = 84.84 A, b = 40.52 A, c = 65.66 A, α = γ= 90°, β = 127.06° with two molecules per A.U. Crystals were flashed cooled in liquid nitrogen, and X-ray data were collected at 100 K on a “NOIR-1” MBC system detector at beam line 4.2.2 at the Advanced Light Source in Berkeley. A native data set was collected to a resolution of 1.85 Å. Data was processed with D*TREK 31. The molecular replacement solution was generated using the program BALBES 32 and the structure of RRM (PDB 1CVJ) as a search model. The protein structure was further refined with CNS 33 and COOT 34 and verified with PROCHECK 35. Statistics are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

PCR Mutagenesis

Mutants of the RRM domain (L39A, E42A, R47A, G48A, F49A, F54A, RRMΔ41–42, RRMΔ41–43, RRMΔ40–43 and RRMΔ40–45) were generated using a QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Strategene).

NMR spectroscopy and sequence specific resonance assignments

Multidimensional heteronuclear NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K on Varian INOVA 800 and 600 MHz spectrometers using pulse field gradients to suppress artifacts and eliminate water signal. Because of the slow exchange regime, all spectra were collected on 1–2 mM uniformly 15N- and 15N/13C-labeled Cyp33 RRM domain (residues 1–90) first in the free form and then in complex with unlabeled MLL PHD3 finger (at a 1:2 ratio of proteins). The amino acid spin system and sequential assignments were made using 1H,15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) and triple-resonance HNCACB 36 and CBCA(CO)NH 37. Spectra were processed with NMRPipe 38 and analyzed using CCPN 39, nmrDraw and in-house software programs on Sun and Silicon Graphics workstations.

NMR titrations

The ligand binding to the wild type and mutant human Cyp33 RRM domain was characterized by monitoring chemical shift changes in 1H,15N HSQC spectra of 0.1–0.2 mM 15N-labeled RRM as either unlabeled MLL PHD3 (up to 0.4 mM), the AAUAAA RNA sequence (up to 0.6 mM), or unlabeled ING1 PHD (up to 1 mM) were added stepwise. The ligand binding to the wild type MLL PHD3 finger was characterized by monitoring chemical shift changes in 1H,15N HSQC spectra of 0.2 mM 15N-labeled PHD3 as unlabeled wild type or mutant human Cyp33 RRM (up to 0.4 mM), or the catalytic domain of human Cyp33 (up to 1 mM) were added gradually. Interaction between 15N-labeled MLL PHD3 (0.1 mM) and unlabeled Drosophila Cyp33 RRM (up to 0.5 mM), and between 15N-labeled Drosophila Cyp33 RRM (0.1 mM) and unlabeled MLL PHD3 (up to 0.5 mM) was tested similarly.

Relaxation experiments

Changes in dynamics of the Cyp33 RRM domain upon binding to the MLL PHD3 finger was investigated by backbone amide 15N relaxation experiments. The 15N R1, R2 and 1H,15N steady state NOE experiments were acquired on an 800 MHz spectrometer at 298 K using the ligand-free and PHD3 (1.5 mM)-bound 15N-labeled RRM 1–90 (1 mM) and analyzed as described previously 40. The 15N R1 and 15N R2 values for the unbound state were determined from the spectra collected with variable T1 delay times (20, 60, 140, 240, 360, 460, 660, 860, and 1110 ms, with times 60 and 860 ms repeated for curve-fitting error) and T2 delay times (10, 30, 50, 70, 90, and 110 ms, with times 30 and 70 ms repeated for curve-fitting error), respectively. The 15N R1 and 15N R2 values for the RRM-PHD3 complex were determined from the spectra collected with variable T1 delay times (20, 60, 140, 240, 360, 460, 660, 860, 1100, and 1500, with times 60 and 1100 ms repeated for curve-fitting error) and T2 delay times (10, 30, 50, 70, and 90 ms, with times 10 and 70 ms repeated for curve-fitting error), respectively. Recovery delays of 1.2 s were used in the measurement of both R1 and R2 values. NOE values were determined from spectra collected either with a 5 s relaxation delay alone or with a proton presaturation period of 3 s preceded by a 2 s relaxation delay. The R1, R2 and NOE values were analyzed using the program Origin.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

The ITC experiments were carried out at 25 C on a VP-ITC calorimeter (MicroCal). The samples (wild type and mutant Cyp33 RRM and MLL PHD3) were dialyzed for 2 days against an assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT and 1 mM NaN3). The heat of the reactions was measured by making 30 sequential injections of 10 μl of PHD3 (0.65 mM) into a 1.41 ml of RRM solution (0.05 mM) (and vice versa) with spacing intervals of 60 seconds. The heat of dilution was measured by injecting the ligand protein into control buffer and subtracted from the raw data before the fitting process. Binding isotherms were analyzed by non-linear least-squares fitting of the data using Microcal ORIGIN software (Microcal).

RT-PCR assays

293T cells were transfected with FLAG-HIS6-CYP33 using the Fugene6 method. After two days RNA was prepared using Trizol (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed using First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in duplicate on the ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detection System. HOXA9 and MEIS1 expression was calculated following normalization to GAPDH levels by the comparative Ct (Cycle threshold) method. Taqman probes and primers used in the study are available upon request.

Accession numbers

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank with accession number 3MDF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Liang Li, Sigrid Nachtergaele and Jennifer Schlegel for discussions and help with the experiments, Jay Nix at beam line 4.2.2 of the ALS in Berkeley for help with data collection and Tara Davis for providing the initial constructs of the RRM and catalytic domains of Cyp33. This research is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, GM074961 and GM075827 (R.F.I.), CA55029 and CA116606 (M.L.C.) and CA113472 and GM071424 (T.G.K.).

Abbreviations

- Cyp33

Cyclophilin 33

- PHD

plant homeodomain

- MLL

Myeloid/lymphoid or Mixed Lineage Leukemia

- ITC

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

- CSP

chemical shift perturbation

- RRM

RNA-recognition motif

- HSQC

Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mi H, Kops O, Zimmermann E, Jaschke A, Tropschug M. A nuclear RNA-binding cyclophilin in human T cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;398:201–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang XJ, Etzkorn FA. Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase inhibitors. Biopolymers. 2006;84:125–46. doi: 10.1002/bip.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Min L, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. A case study of proline isomerization in cell signaling. Front Biosci. 2005;10:385–97. doi: 10.2741/1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Han R, Zhang W, Yuan Y, Zhang X, Long Y, Mi H. Human CyP33 binds specifically to mRNA and binding stimulates PPIase activity of hCyP33. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:835–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fair K, Anderson M, Bulanova E, Mi H, Tropschug M, Diaz MO. Protein interactions of the MLL PHD fingers modulate MLL target gene regulation in human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3589–97. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3589-3597.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Santillan DA, Koonce M, Wei W, Luo R, Thirman MJ, Zeleznik-Le NJ, Diaz MO. Loss of MLL PHD finger 3 is necessary for MLL-ENL-induced hematopoietic stem cell immortalization. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6199–207. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayton PM, Cleary ML. Molecular mechanisms of leukemogenesis mediated by MLL fusion proteins. Oncogene. 2001;20:5695–707. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess JL. MLL: a histone methyltransferase disrupted in leukemia. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:500–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yano T, Nakamura T, Blechman J, Sorio C, Dang CV, Geiger B, Canaani E. Nuclear punctate distribution of ALL-1 is conferred by distinct elements at the N terminus of the protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7286–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birke M, Schreiner S, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Mahr K, Titgemeyer F, Slany RK. The MT domain of the proto-oncoprotein MLL binds to CpG-containing DNA and discriminates against methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:958–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen MD, Grummitt CG, Hilcenko C, Min SY, Tonkin LM, Johnson CM, Freund SM, Bycroft M, Warren AJ. Solution structure of the nonmethyl-CpG-binding CXXC domain of the leukaemia-associated MLL histone methyltransferase. Embo J. 2006;25:4503–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ernst P, Wang J, Huang M, Goodman RH, Korsmeyer SJ. MLL and CREB bind cooperatively to the nuclear coactivator CREB-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2249–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2249-2258.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura T, Mori T, Tada S, Krajewski W, Rozovskaia T, Wassell R, Dubois G, Mazo A, Croce CM, Canaani E. ALL-1 is a histone methyltransferase that assembles a supercomplex of proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1119–28. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milne TA, Briggs SD, Brock HW, Martin ME, Gibbs D, Allis CD, Hess JL. MLL targets SET domain methyltransferase activity to Hox gene promoters. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1107–17. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Southall SM, Wong PS, Odho Z, Roe SM, Wilson JR. Structural basis for the requirement of additional factors for MLL1 SET domain activity and recognition of epigenetic marks. Mol Cell. 2009;33:181–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider J, Wood A, Lee JS, Schuster R, Dueker J, Maguire C, Swanson SK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Shilatifard A. Molecular regulation of histone H3 trimethylation by COMPASS and the regulation of gene expression. Mol Cell. 2005;19:849–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel A, Dharmarajan V, Cosgrove MS. Structure of WDR5 bound to mixed lineage leukemia protein-1 peptide. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32158–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel A, Vought VE, Dharmarajan V, Cosgrove MS. A conserved arginine-containing motif crucial for the assembly and enzymatic activity of the mixed lineage leukemia protein-1 core complex. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32162–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song JJ, Kingston RE. WDR5 interacts with mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) protein via the histone H3-binding pocket. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35258–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806900200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steward MM, Lee JS, O'Donovan A, Wyatt M, Bernstein BE, Shilatifard A. Molecular regulation of H3K4 trimethylation by ASH2L, a shared subunit of MLL complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:852–4. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia ZB, Anderson M, Diaz MO, Zeleznik-Le NJ. MLL repression domain interacts with histone deacetylases, the polycomb group proteins HPC2 and BMI-1, and the corepressor C-terminal-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8342–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1436338100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muntean AG, Giannola D, Udager AM, Hess JL. The PHD fingers of MLL block MLL fusion protein-mediated transformation. Blood. 2008;112:4690–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vitali J, Ding J, Jiang J, Zhang Y, Krainer AR, Xu RM. Correlated alternative side chain conformations in the RNA-recognition motif of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1531–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peña PV, Davrazou F, Shi X, Walter KL, Verkhusha VV, Gozani O, Zhao R, Kutateladze TG. Molecular mechanism of histone H3K4me3 recognition by plant homeodomain of ING2. Nature. 2006;442:100–3. doi: 10.1038/nature04814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peña PV, Hom RA, Hung T, Lin H, Kuo AJ, Wong RP, Subach OM, Champagne KS, Zhao R, Verkhusha VV, Li G, Gozani O, Kutateladze TG. Histone H3K4me3 binding is required for the DNA repair and apoptotic activities of ING1 tumor suppressor. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:303–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clery A, Blatter M, Allain FH. RNA recognition motifs: boring? Not quite. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:290–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hargous Y, Hautbergue GM, Tintaru AM, Skrisovska L, Golovanov AP, Stevenin J, Lian LY, Wilson SA, Allain FH. Molecular basis of RNA recognition and TAP binding by the SR proteins SRp20 and 9G8. Embo J. 2006;25:5126–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdul-Manan N, O'Malley SM, Williams KR. Origins of binding specificity of the A1 heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3545–54. doi: 10.1021/bi952298p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadler SG, Merrill BM, Roberts WJ, Keating KM, Lisbin MJ, Barnett SF, Wilson SH, Williams KR. Interactions of the A1 heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein and its proteolytic derivative, UP1, with RNA and DNA: evidence for multiple RNA binding domains and salt-dependent binding mode transitions. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2968–76. doi: 10.1021/bi00225a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Mustafi D, Fu Q, Tereshko V, Chen DL, Tice JD, Ismagilov RF. Nanoliter microfluidic hybrid method for simultaneous screening and optimization validated with crystallization of membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607502103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pflugrath JW. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:1718–25. doi: 10.1107/s090744499900935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Long F, Vagin AA, Young P, Murshudov GN. BALBES: a molecular-replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;64:125–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907050172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macronolacular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittekind M, Mueller L. HNCACB, A high-sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha-carbon and beta-carbon resonances in proteins. J Magn Reson. 1993;101:201–5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grzesiek S, Bax A. Improved 3D triple-resonance NMR techniques applied to a 31-kDa protein. J Magn Reson. 1992;96:432–40. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–96. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheever ML, Kutateladze TG, Overduin M. Increased mobility in the membrane targeting PX domain induced by phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1873–82. doi: 10.1110/ps.062194906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.